Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana L.) Processing By-Products as Potential Functional Ingredients in Food Production: A Detailed Insight into Phytochemical Composition and Antioxidant Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

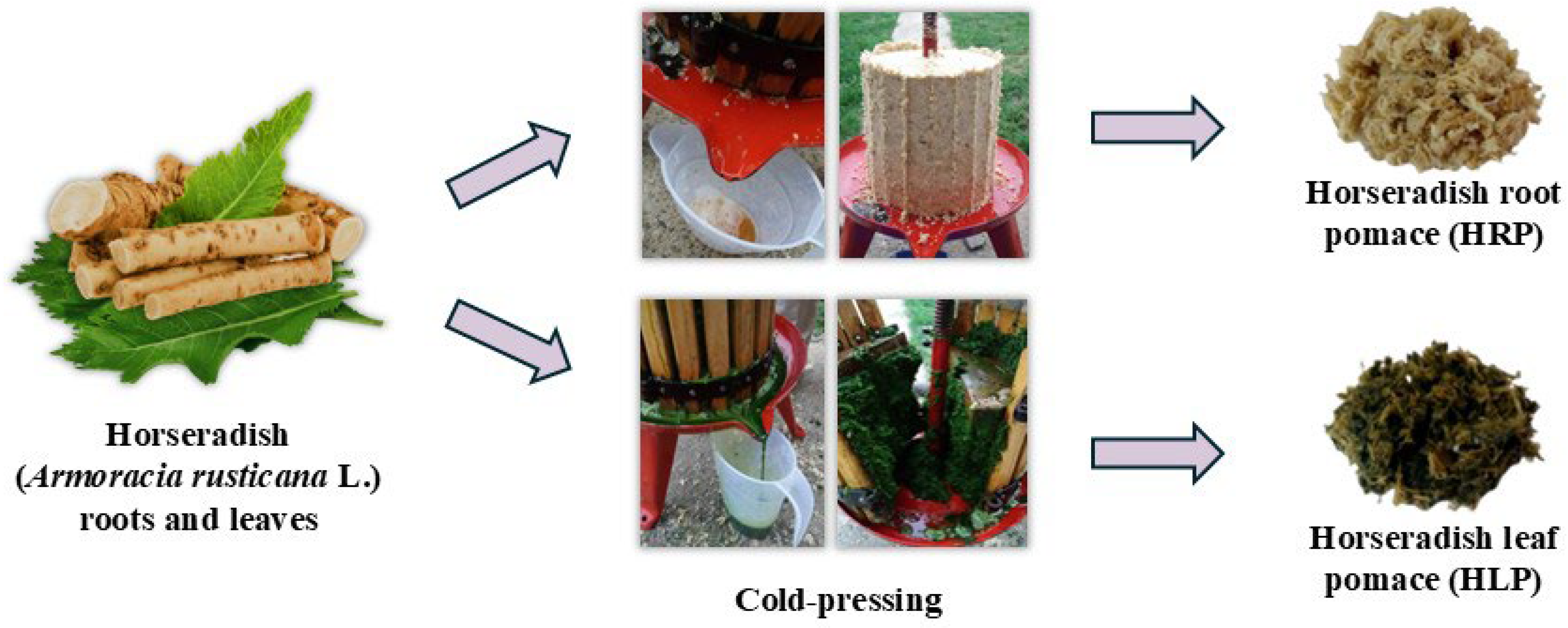

2.2. Horsereadish Root and Leaf By-Products

2.3. Moisture Content

2.4. Chromatographic Analysis of the Pomaces

2.4.1. Preparation of the Pomaces for Chromatographic Analysis

2.4.2. UHPLC Q-ToF-MS Analysis

2.5. Spectrophotometric Analysis of the Pomaces

2.5.1. Preparation of the Pomaces for Spectrophotometric Analysis

2.5.2. Total Phenolics, Flavonoids, and Phenolic (Hydroxycinnamic) Acids in Pomaces

2.5.3. Antioxidant Properties of the Pomaces

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Moisture Content

3.2. UHPLC Q-ToF-MS Analysis

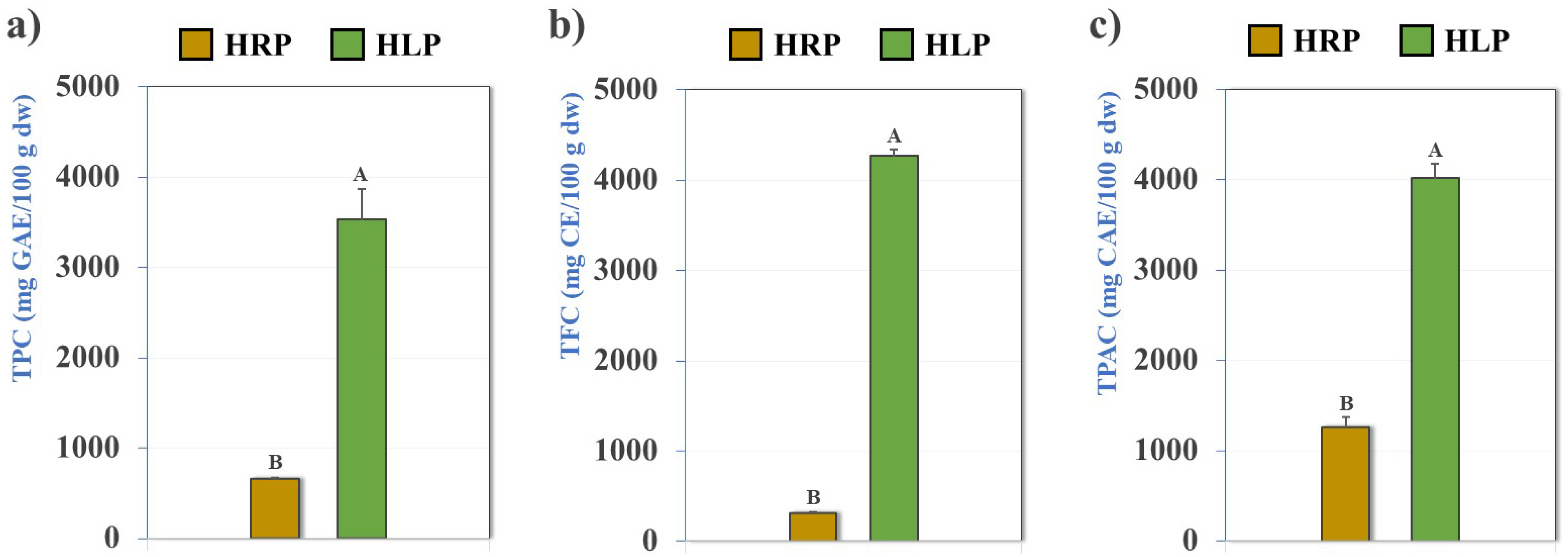

3.3. Total Phenolic, Flavonoid, and Phenolic (Hydroxycinnamic) Acid Contents

3.4. Antioxidant Activity

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kultys, E.; Moczkowska-Wyrwisz, M. Effect of using carrot pomace and beetroot-apple pomace on physicochemical and sensory properties of pasta. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 168, 113858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skwarek, P.; Karwowska, M. Fruit and vegetable processing by-products as functional meat product ingredients-a chance to improve the nutritional value. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 189, 115442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, M.I.; Ungureanu-Iuga, M.; Mironeasa, S. Carrot pomace characterization for application in cereal-based products. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majerska, J.; Michalska, A.; Figiel, A. A review of new directions in managing fruit and vegetable processing by-products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 88, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agneta, R.; Möllers, C.; Rivelli, A.R. Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana), a neglected medical and condiment species with a relevant glucosinolate profile: A review. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2013, 60, 1923–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrone, L.; Larocca, M.; Marzocco, S.; Martelli, G.; Rossano, R. Total phenols and flavonoids content, antioxidant capacity and lipase inhibition of root and leaf horseradish (Armoracia rusticana) extracts. Food Nutr. Sci. 2015, 6, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negro, E.J.; Sendker, J.; Stark, T.; Lipowicz, B.; Hensel, A. Phytochemical and functional analysis of horseradish (Armoracia rusticana) fermented and non-fermented root extracts. Fitoterapia 2022, 162, 105282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, N.; Gonda, S.; Kiss-Szikszai, A.; Plaszkó, T.; Lőrincz, P.; Vasas, G. Ethnobotanical and ethnopharmacological data of Armoracia rusticana P. Gaertner, B. Meyer et Scherb. in Hungary and Romania: A case study. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2018, 65, 1893–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.M.; Gonda, S.; Vasas, G. A Review on the phytochemical composition and potential medicinal uses of horseradish (Armoracia rusticana) root. Food Rev. Int. 2013, 29, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomsone, L.; Galoburda, R.; Kruma, Z.; Durrieu, V.; Cinkmanis, I. Microencapsulation of horseradish (Armoracia rusticana L.) juice using spray-drying. Foods 2020, 9, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, J.; Salević-Jelić, A.; Milinčić, D.; Gašić, U.; Pavlović, V.; Rabrenović, B.; Pešić, M.B.; Lević, S.M.; Mihajlović, D.M.; Nedović, V. Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana L.) leaf juice encapsulated within polysaccharides-blend-based carriers: Characterization and application as potential antioxidants in mayonnaise production. Food Chem. 2025, 464, 141777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, J.M.; Salević-Jelić, A.S.; Milinčić, D.D.; Gašić, U.M.; Pavlović, V.B.; Rabrenović, B.B.; Pešić, M.B.; Lević, S.M.; Nedović, V.A.; Mihajlović, D.M. Encapsulated horseradish (Armoracia rusticana L.) root juice: Physicochemical characterization and the effects of its addition on the oxidative stability and quality of mayonnaise. J. Food Eng. 2024, 381, 112189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomsone, L.; Galoburda, R.; Kruma, Z.; Majore, K. Physicochemical properties of biscuits enriched with horseradish (Armoracia rusticana L.) products and bioaccessibility of phenolics after simulated human digestion. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2020, 70, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Determination of moisture, ash, protein and fat. In Official Method of Analysis of the Association of Analytical Chemists, 18th ed.; Association of Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kostić, A.; Milinčić, D.D.; Špirović Trifunović, B.; Nedić, N.; Gašić, U.M.; Tešić, Ž.L.; Pešić, M. Monofloral corn poppy bee-collected pollen—A detailed insight into its phytochemical composition and antioxidant properties. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agneta, R.; Lelario, F.; De Maria, S.; Möllers, C.; Bufo, S.A.; Rivelli, A.R. Glucosinolate profile and distribution among plant tissues and phenological stages of field-grown horseradish. Phytochemistry 2014, 106, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomsone, L.; Kruma, Z.; Galoburda, R.; Talou, T. Composition of volatile compounds of horseradish roots (Armoracia rusticana L.) depending on the genotype. Rural Sustain. Res. 2013, 29, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotirić Akšić, M.; Pešić, M.; Pećinar, I.; Dramićanin, A.; Milinčić, D.; Kostić, A.; Gašić, U.; Jakanovski, M.; Kitanović, M.; Meland, M. Diversity and Chemical Characterization of Apple (Malus sp.) Pollen: High Antioxidant and Nutritional Values for Both Humans and Insects. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.O.; Jeong, W.; Lee, C.Y. Antioxidant capacity of phenolic phytochemicals from various cultivars of plums. Food Chem. 2003, 81, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matkowski, A.; Tasarz, P.; Szypuła, E. Antioxidant activity of herb extracts from five medicinal plants from Lamiaceae, subfamily Lamioideae. J. Med. Plants Res. 2008, 2, 321–330. [Google Scholar]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salević, A.; Stojanović, D.; Lević, S.; Pantić, M.; Ðordević, V.; Pešić, R.; Bugarski, B.; Pavlović, V.; Uskoković, P.; Nedović, V. The structuring of Sage (Salvia officinalis L.) extract-incorporating edible zein-based materials with antioxidant and antibacterial functionality by solvent casting versus electrospinning. Foods 2022, 11, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: The FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knez, E.; Kadac-Czapska, K.; Dmochowska-Ślęzak, K.; Grembecka, M. Root vegetables—Composition, health effects, and contaminants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, S.; Kalia, K.; Sharma, M.; Singh, B.; Ahuja, P.S. Processing of apple pomace for bioactive molecules. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2008, 28, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muntean, M.V.; Fărcaş, A.C.; Medeleanu, M.; Salanţă, L.C.; Borşa, A. A sustainable approach for the development of innovative products from fruit and vegetable by-products. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, D.J. Antioxidant Properties of Spices, Herbs and Other Sources; Springer Science & Business Media: Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomsone, L.; Galoburda, R.; Kruma, Z.; Cinkmanis, I. Characterization of dried horseradish leaves pomace: Phenolic compounds profile and antioxidant capacity, content of organic acids, pigments and volatile compounds. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2020, 246, 1647–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karafyllaki, D.; Narwojsz, A.; Kurp, L.; Sawicki, T. Effects of different processing methods on the polyphenolic compounds profile and the antioxidant and anti-glycaemic properties of horseradish roots (Armoracia rusticana). Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2023, 249, 1739–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomsone, L.; Kruma, Z. Stability of rapeseed oil with horseradish Amorica rusticana L. and lovage Levisticum officinale L. extracts under medium temperature accelerated storage conditions. Agron. Res. 2015, 13, 1120–1130. [Google Scholar]

- Gimsing, A.L.; Kirkegaard, J.A. Glucosinolates and biofumigation: Fate of glucosinolates and their hydrolysis products in soil. Phytochem. Rev. 2009, 8, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyeneche, R.; Roura, S.; Ponce, A.; Vega-Gálvez, A.; Quispe-Fuentes, I.; Uribe, E.; Di Scala, K. Chemical characterization and antioxidant capacity of red radish (Raphanus sativus L.) leaves and roots. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 16, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathi, M.H.; Molan, A.L.; Ismail, M.H. The free radical scavenging activities and total phenolic contents of extracts from leaves and roots of two radish varieties grown in Iraq. Biochem. Cell. Arch. 2019, 19, 1313. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, S.W.; Ghimeray, A.K.; Park, C.H. Investigation of total phenolic, total flavonoid, antioxidant and allyl isothiocyanate content in the different organs of Wasabi Japonica grown in an organic system. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 11, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.D.; McFeeters, R.F.; Thompson, R.T.; Dean, L.L.; Shofran, B. Phenolic acid content and composition in leaves and roots of common commercial sweetpotato (Ipomea batatas L.) cultivars in the United States. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, C343–C349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petridis, A.; Therios, I.; Samouris, G.; Tananaki, C. Salinity-induced changes in phenolic compounds in leaves and roots of four olive cultivars (Olea europaea L.) and their relationship to antioxidant activity. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2012, 79, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppusamy, S.; Venkateswarlu, K.; Megharaj, M. Examining the polyphenol content, antioxidant activity and fatty acid composition of twenty-one different wastes of fruits, vegetables, oilseeds and beverages. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ademoyegun, O.T.; Akin-Idowu, P.E.; Ibitoye, D.O.; Adewuyi, G.O. Phenolic contents and free radical scavenging activity in some leafy vegetables. Int. J. Veg. Sci. 2013, 19, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Baño, M.J.; Lorente, J.; Castillo, J.; Benavente-García, O.; Marín, M.P.; Del Río, J.A.; Ortuño, A.; Ibarra, I. Flavonoid distribution during the development of leaves, flowers, stems, and roots of Rosmarinus officinalis. Postulation of a biosynthetic pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 4987–4992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, A.; Sultana, B.; Bashir, A.; Ghaffar, A.; Munir, B.; Shar, G.A.; Nazir, A.; Iqbal, M. Evaluation of antioxidant potential of vegetables waste. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2018, 27, 947–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solaberrieta, I.; Jiménez, A.; Cacciotti, I.; Garrigós, M.C. Encapsulation of bioactive compounds from aloe vera agrowastes in electrospun poly (ethylene oxide) nanofibers. Polymers 2020, 12, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Upadhyay, N.; Singh, A.K.; Meena, G.S.; Arora, S. Organic solvent-free extraction of carotenoids from carrot bio-waste and its physico-chemical properties. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 4678–4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, L.; Fröhlich, K.; Böhm, V. Comparative antioxidant activities of carotenoids measured by ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP), ABTS bleaching assay (αTEAC), DPPH assay and peroxyl radical scavenging assay. Food Chem. 2011, 129, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadez-Carmona, L.; Plazola-Jacinto, C.P.; Hernández-Ortega, M.; Hernández-Navarro, M.D.; Villarreal, F.; Necoechea-Mondragón, H.; Ortiz-Moreno, A.; Ceballos-Reyes, G. Effects of microwaves, hot air and freeze-drying on the phenolic compounds, antioxidant capacity, enzyme activity and microstructure of cacao pod husks (Theobroma cacao L.). Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2017, 41, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chada, P.S.N.; Santos, P.H.; Rodrigues, L.G.G.; Goulart, G.A.S.; Azevedo dos Santos, J.D.; Maraschin, M.; Lanza, M. Non-conventional techniques for the extraction of antioxidant compounds and lycopene from industrial tomato pomace (Solanum lycopersicum L.) using spouted bed drying as a pre-treatment. Food Chem. X 2022, 13, 100237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No | RT | Formula | Compound Name | Calculated Mass | m/z Exact Mass | mDa | Fragmentation | HRP | HLP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolic acids and derivatives | mg/100 g dw | ||||||||

| 1 | 2.42 | C13H15O9− | Dihydrobenzoic acid hexoside is. I b | 315.0722 | 315.0749 | −2.69 | 153.0196 [C7H5O4]−; 109.0302 [C7H5O4–CO2]− | 7.98 | / |

| 2 | 3.91 | C13H15O9− | Dihydroxybenzoic acid hexoside is. II b | 315.0722 | 315.0750 | −2.84 | 153.0200 [C7H5O4]−; 152.0124 [C7H5O4–H]−; 109.0309 [C7H5O4–CO2]− | 46.61 | 1.29 |

| 3 | 4.50 | C7H5O3− | Hydroxybenzoic acid is. I b | 137.0244 | 137.0254 | −0.99 | / | 18.11 | 17.08 |

| 4 | 5.19 | C15H19O10− | Syringic acid hexoside b | 359.0978 | 359.1021 | −4.30 | 197.0466 [C9H9O5]−; 153.0564 [C9H9O5–CO2]−; 167.0007 [C9H9O5–2CH3]−; 182.0228 [C9H9O5–CH3]−; 138.0324 [C9H9O5–CO2–CH3]− | / | 11.94 |

| 5 | 5.86 | C7H5O4− | Dihydroxybenzoic acid b | 153.0193 | 153.0208 | −1.44 | 109.0294 [M–H–CO2]−; 108.0219 [M–2H–CO2]−; | 2.20 | <LOQ |

| 6 | 8.29 | C7H5O3− | Hydroxybenzoic acid is. II b | 137.0244 | 137.0250 | −0.62 | / | 21.64 | / |

| ∑ | 96.54 | 30.31 | |||||||

| Flavonols and derivatives | |||||||||

| 7 | 6.47 | C32H37O20− | Kaempferol 3-O-(2″-pentosyl)hexoside−7-O-hexoside c | 741.1878 | 741.1975 | −9.69 | 579.1381 [M–H–Hex]−; 447.0919 [M–H–Hex–Pent]−; 446.0863 [M–2H–Hex–Pent]−; 429.0890 [M–H–Hex–Pent–H2O]−; 285.0395 [Y0]–; 284.0341 [Y0–H]− | / | 33.77 |

| 8 | 7.41 | C26H27O16− | Quercetin 3-O-(6″-pentosyl)hexoside c | 595.1299 | 595.1388 | −8.92 | 301.0349 [Y0]–; 300.0304 [Y0–H]−; 271.0255 [Y0–2H–CO]−; 151.0040[1,3A]– | / | 18.05 |

| 9 | 7.47 | C27H29O16− | Kaempferol 3-O-(2″-hexosyl)hexoside c | 609.1456 | 609.1512 | −5.58 | 429.0862 [M–H–Hex–H2O]−; 285.0411 [Y0]–; 284.0338 [Y0–H ]−; 255.0309 [Y0–CH2O]−; 227.0343 [Y0–CH2O–CO]− | 12.14 | 31.98 |

| 10 | 7.81 | C26H27O15− | Kaempferol 3-O-(2″-pentosyl)hexoside c | 579.1350 | 579.1410 | −6.02 | 429.0844 [M–H–Pent–H2O]−; 285.0410 [Y0]–; 284.0356 [Y0–H]−; 255.0309 [Y0–CH2O]−; 227.0379 [Y0–CH2O–CO]− | 62.83 | 376.30 |

| 11 | 7.82 | C15H9O7− | Morin c | 301.0348 | 301.0402 | −5.41 | 107.0151 [0,4A]–; 151.0046 [1,3A]−; 179.0005 [1,2A]− | 62.21 | <LOQ |

| 12 | 8.09 | C27H29O15− | Kaempferol 3-O-(6″-rhamnosyl)hexoside c | 593.1506 | 593.1605 | −9.88 | 285.0418 [Y0]–; 284.0344 [Y0–H]−; 255.0309 [Y0–CH2O]− | 11.95 | <LOQ |

| 13 | 8.22 | C25H25O14− | Kaempferol 3-O-(2″-pentosyl)pentoside c | 549.1244 | 549.1293 | −4.94 | 417.0847 [M–H–Pent]–; 399.0736 [M–H–Pent–H2O]−; 285.0398 [Y0]–; 284.0341 [Y0–H ]−; 255.0309 [Y0–CH2O]−; 227.0337 [Y0–CH2O–CO]− | 23.34 | 2.84 |

| 14 | 8.49 | C24H21O14− | Kaempferol 3-O-(6″-malonyl)hexoside c | 533.0931 | 533.0985 | −5.36 | 489.1060 [M–H–Malonyl moiety]−; 285.0410 [Y0]–; 284.0338 [Y0–H ]−; 257.0352 [Y0–CO]–; 255.0316 [Y0–CH2O]− | 9.34 | / |

| 15 | 9.43 | C15H9O7− | Quercetin a | 301.0354 | 301.0390 | −3.57 | 107.0141 [0,4A]–; 121.0301 [1,2B]−; 151.0038 [1,3A]–; 178.9997 [1,2A]− | 12.12 | / |

| 16 | 10.24 | C15H9O6− | Kaempferol c | 285.0405 | 285.0434 | −2.91 | 285.0422 [M–H]−; 239.0354 [M–H–CO–H2O]−; 229.0508 [M–H–2CO]−; 211.0401 [M–H–2CO–H2O]−; 185.0609 [M–H–2CO–CO2]−; 151.0067 [1,3A]−; | 236.09 | 13.96 |

| 17 | 10.45 | C16H11O7− | Isorhamnetin c | 315.0510 | 315.0539 | −2.88 | 300.0279 [M–H–CH3]−; 271.0269 [M–2H–CH3–CO]−; 151.0038 [1,3A]− | <LOQ | / |

| ∑ | 430.02 | 476.90 | |||||||

| ∑∑ | 526.56 | 507.21 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marković, J.M.; Salević, A.S.; Milinčić, D.D.; Gašić, U.M.; Đorđević, V.B.; Rabrenović, B.B.; Pešić, M.B.; Lević, S.M.; Mihajlović, D.M.; Nedović, V.A. Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana L.) Processing By-Products as Potential Functional Ingredients in Food Production: A Detailed Insight into Phytochemical Composition and Antioxidant Properties. Separations 2025, 12, 330. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations12120330

Marković JM, Salević AS, Milinčić DD, Gašić UM, Đorđević VB, Rabrenović BB, Pešić MB, Lević SM, Mihajlović DM, Nedović VA. Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana L.) Processing By-Products as Potential Functional Ingredients in Food Production: A Detailed Insight into Phytochemical Composition and Antioxidant Properties. Separations. 2025; 12(12):330. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations12120330

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarković, Jovana M., Ana S. Salević, Danijel D. Milinčić, Uroš M. Gašić, Verica B. Đorđević, Biljana B. Rabrenović, Mirjana B. Pešić, Steva M. Lević, Dragana M. Mihajlović, and Viktor A. Nedović. 2025. "Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana L.) Processing By-Products as Potential Functional Ingredients in Food Production: A Detailed Insight into Phytochemical Composition and Antioxidant Properties" Separations 12, no. 12: 330. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations12120330

APA StyleMarković, J. M., Salević, A. S., Milinčić, D. D., Gašić, U. M., Đorđević, V. B., Rabrenović, B. B., Pešić, M. B., Lević, S. M., Mihajlović, D. M., & Nedović, V. A. (2025). Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana L.) Processing By-Products as Potential Functional Ingredients in Food Production: A Detailed Insight into Phytochemical Composition and Antioxidant Properties. Separations, 12(12), 330. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations12120330