Abstract

Agro-industrial chestnut waste derived from chestnut processing is usually discharged without further use. However, these residues are attractive due to their high-value composition, rich in sugars and lignin. Among these residues, chestnut burrs (CB) represent a promising feedstock for biorefinery applications aimed at maximizing the valorization of their main constituents. In this study, we propose an environmentally friendly approach based on deep eutectic solvents (DES) formed by choline chloride and urea (ChCl/U) (1:2, mol/mol) for the selective deconstruction of lignocellulosic architecture, followed by enzymatic hydrolysis to release second-generation (2G) fermentable sugars. Pretreatments were applied to raw CB, washed CB (W-CB), and the obtained solid fraction after prehydrolysis (PreH). Structural and morphological modifications, as well as crystallinity induced by DES pretreatment, were characterized using attenuated total reflectance Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR), field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM), and X-ray diffraction (XRD). Remarkable results in terms of effectiveness and environmental friendliness on saccharification yields were achieved for PreH subjected to DES treatment for 8 h, reaching approximately 60% glucan and 74% xylan conversion under the lower enzyme loading (23 FPU/g) and liquid-to-solid ratio (LSR) of 20:1 studied. This performance significantly reduces DES pretreatment time from 16 h to 8 h at mild conditions (100 °C), lowers the LSR for enzymatic hydrolysis from 30:1 to 20:1, and decreases enzyme loading from 63.5 FPU/g to 23 FPU/g, therefore improving process efficiency and sustainability.

1. Introduction

Chestnut processing is an emerging sector in the European Union with an increasing production of more than 60% in recent years [1]. Particularly, Spain remains the largest EU producer, with around 182.000 tons of harvested production in 2024 [2]. Consequently, managing the waste produced in this activity is of great interest, following the new guidelines and legislation around zero-waste processes and circular bioeconomy, which has received much attention in recent years as a solution to surmount the present consumption and production demands [3].

Waste derived from chestnut management, including shells, burrs, leaves, and pruning, shows a relevant presence of carbohydrates in its composition [4]. Specifically, burrs made up around 50% on a dry basis, making them a good candidate to obtain monomeric sugars [5]. Nevertheless, the presence of lignin in these materials hinders the recovery of carbohydrates since this polymer acts like a barrier due to the interaction with cellulase enzymes [6] and consequently limits the hydrolysis of cellulose and hemicellulose polymers to produce second-generation (2G) monomeric sugars [7]. Additionally, cellulose crystallinity is another parameter associated with biomass recalcitrance and restriction to the action of enzymes [8,9]. Consequently, it plays a significant role as a predictor of enzymatic hydrolysis as well as the effectiveness of the pretreatment [10]. In this sense, pretreatments are indispensable to deconstructing the lignocellulosic complex, improving the accessibility of the hydrolytic enzymes to the carbohydrate fraction, and consequently improving both the hydrolysis rate and amount of 2G sugars released after enzymatic hydrolysis [11,12].

The use of conventional pretreatments, namely diluted alkali using NaOH as a reagent, is extensively used on biomass due to the great removal of lignin and partial elimination of hemicellulose. Although some disadvantages have been cited as a result of its use, such as costs for NaOH recovery, its environmental impact, or possible condensation of lignin and changes in cellulose towards a more stable structure, which could make enzymatic hydrolysis difficult [13,14,15]. Furthermore, it is estimated that around 30% lower energy consumption is achieved by using a deep eutectic solvent (DESs) pretreatment compared to the pretreatment with NaOH under the same pretreatment conditions [16]. Thus, the use of mild alkaline-neutral DES, such as choline chloride/urea (ChCl/U), seems to be more feasible from an environmentally friendly point of view than conventional routes.

Therefore, the use of DES as eco-friendly solvents in biorefinery processing has gained special attention in recent years [17,18,19], since DES show interesting properties as low cost, low vapor pressure, biodegradability, and non-flammability, whereby they are commonly distinguished as green solvents [20]. Particularly, in our previous work, DES pretreatment using diluted ChCl/U showed relevant physicochemical changes on chestnut burrs (CB) [5].

For these reasons, this work aims to develop a novel and efficient biorefinery process to improve the conversion of carbohydrates present in CB into fermentable 2G sugars via DES and subsequent enzymatic hydrolysis. Unlike previous works, our contribution lies in integrating diluted DES pretreatment with systematic evaluation of raw CB, washed CB, and solid residues after prehydrolysis, using ChCl as a hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) and urea as a hydrogen bond donor (HBD). We hypothesize that DES pretreatment significantly modifies the crystalline structure of CB, therefore improving enzymatic digestibility and reducing enzyme requirements. To test this, we combined carbohydrate-rich materials (CRMs), including those obtained in our previous study (Part I) [5], and assessed their hydrolysis under varying solid loads. Structural characterization (ATR-FTIR, XRD, SEM) was performed to correlate crystallinity changes with hydrolysis efficiency. Finally, enzyme loading was optimized to minimize costs while maintaining high sugar yields, reinforcing the potential of this integrated process for cost-effective biorefinery applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of DES

ChCl (>99%) and urea (>99.5%) were provided by Sigma-Aldrich (Merk Life Science S.L., Tres Cantos, Madrid, Spain). The moisture of the ChCl was maintained in a gel desiccator. DES was prepared by mixing ChCl and urea with a molar ratio of 1:2 (mol/mol) and placed in a water bath at 60 °C with stirring until a colorless liquid was obtained [21]. Then, the mixture ChCl/U was homogenized by adding water at a ratio of 80:20 DES/water (v/v) under magnetic stirring.

2.2. Substrates of DES Pretreatment

CBs were provided by local cultivars (Vilardevós, Ourense, Spain) in 2019. Then, they were dried at room temperature and homogenized by milling (SOGO mill, SS-5430 models, Sanysan Appliances SL, Valencia, Spain). The substrates assayed for DES treatments were

- -

- Untreated CB

- -

- Washed CB (W-CB) obtained by mixing untreated CB with distilled water in a glass bottle with an SLR of 1:8 (w/v), followed by agitation in an orbital shaker (Optic Ivymen System, Comecta S.A., distributed by Scharlab, Madrid, Spain) at 50 °C, 150 rpm for 4 h. The solid fraction was recovered by filtration and dried at 50 °C (Celsius 2007, Memmert, Schwabach, Germany).

- -

- CB from prehydrolysis (PreH). Untreated CB was pretreated with diluted H2SO4 under the conditions reported by Costa-Trigo et al. [4]. The solid fraction was recovered, washed with distilled water until neutral pH, and dried at 50 °C (Celsius 2007, Memmert, Schwabach, Germany).

2.3. DES Pretreatment

DES pretreatments were carried out according to the best conditions found in our previous work (Part I) [5]. Briefly, 0.5 g of substrate was mixed with diluted ChCl/U in an SLR of 1:20 (w/w) at 100 °C for 4, 8, and 16 h. Then, 50 mL of antisolvent (water) was added and stirred for 30 min. CRMs recovered were washed with 40 mL of water and centrifuged (Ortoalresa, Consul 21, EBA 20, Hettich Zentrifugen, Germany) at 3700 rpm for 15 min. The washing process was repeated three times. Finally, CRMs were dried at 50 °C to remove excess water and stored until physicochemical analysis was performed (Section 2.5).

2.4. Enzymatic Hydrolysis

Sigma-Aldrich (Spain) provided the multienzyme complex CellicCTec2 with the following activities: cellulase 254.50 ± 4.53 (FPU/mL), cellobiose 89.53 ± 0.43 (U/mL), and xylanase 12084.88 ± 169.53 (U/mL) [22].

Samples of untreated CB, W-CB, PreH, and all CRMs obtained after DES pretreatments were enzymatically hydrolyzed. A certain volume of citrate buffer (pH 5) was added to achieve an LSR of 30:1 (v/w), and commercial enzyme Cellic CTec2 (23, 40, 63, 127, 190, and 254 FPU/g) was added under sterile conditions. Afterwards, glass tubes were placed in an orbital shaker (Optic Ivymen System, Comecta S.A., distributed by Scharlab, Madrid, Spain) and incubated at 50 °C and 250 rpm for 72 h.

At the end of the enzymatic hydrolysis, samples were boiled for 5 min to inactivate the enzymes. Then, the samples were centrifuged at 3700 rpm for 10 min (Ortoalresa, Consul 21, EBA 20, Hettich Zentrifugen, Germany) and filtered through 0.22 µm pore membranes (Sartorius, Goettingen, Germany) to be analyzed by HPLC (Agilent, model 1200, Palo Alto, CA, USA) following the methodology described by Costa-Trigo et al. [23] and used to calculate the percentage of saccharification as it was described by Costa-Trigo et al. [24].

2.5. Analytical Methods

2.5.1. Lignocellulosic Composition

The characterization of the lignocellulosic substrates and CRMs was performed by quantitative acid hydrolysis according to the official method NREL/TP-510-42618 [25]. Total lignin was calculated as the sum of acid-soluble lignin (ASL) and acid-insoluble lignin (AIL).

2.5.2. Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier-Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) Spectroscopy

The spectra of PreH and CRMs after DES pretreatments on PreH were obtained by attenuated total reflection (ATR) equipped with a diamond crystal (Smart Orbit Diamond ATR, Thermo Fisher, USA) and coupled to infrared spectroscopy equipment (Thermo Nicolet 6700 FTIR Spectrometer, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Madison, WI, USA). A deuterated triglycine sulfate (DTGS) KBr detector was employed to analyze dry samples with a resolution of 4 cm−1 and 20 scans, in the range of 4000–400 cm−1.

From FTIR spectra, the Lateral order index (LOI) was calculated as the ratio between 1430 and 898 cm−1 absorbances (Equation (1)) [26]; total crystalline index (TCI) was defined as the quotient between the values of absorbances at 1372 and 2900 cm−1 [27] (Equation (2)); and the hydrogen bond intensity (HBI) was calculated as the ratio between 3400 cm−1 and 1320 cm−1 absorbances [26].

LOI, TCI, and HBI were calculated for all samples tested, the initial and DES pretreated samples.

2.5.3. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

Crystallinity index (CrI) was obtained by X-ray spectroscopy (Siemens D5000 Difractometer) through the diffraction angles spanning from 2θ = 2–45°, with a step size of 0.02° and a step time of 0.5 s. The values obtained for the intensity of the crystalline region at 2θ = 22.35 (Icry) and intensity of the amorphous region at 2θ = 16.17 (Iam) were used following Equation (4) [28]:

2.5.4. Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM)

The morphological changes in the lignocellulosic substrates and CRMs were performed by an FE-SEM system (Model JSM-6700 F, Jeol, Japan). The dry material was mounted onto aluminum stubs and coated with gold, and the sputter coater (Sputtering Emitech K550X, Quorum Technologies, Kent, UK) was used to analyze for 3 min.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All data were submitted to one-way ANOVA of the Statgraphics statistical package (Statgraphics Centurion XVI version 16.1.11). Statistically significant differences between means, with a confidence level of 95%, were determined through a least significant difference (LSD) test.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Crystallinity of Lignocellulosic Starting Materials

The lignocellulosic composition of substrates and CRMs was reported in our previous work [5]. However, it was added in Section 3 to join the crystallinity of materials to try to acquire enough information about biomasses before and after the sample preparation, with the objective of searching for relationships between the fractions that form biomasses and their crystallinity parameters. Washing of biomass influenced crystallinity, which could have an impact on further enzymatic hydrolysis of materials, due to the removal of free sugars and partial extractives present in CB, as was previously observed in our previous work [5].

Thus, in addition to the lignocellulosic composition of substrates, a deeper knowledge about the changes experienced by the materials before DES treatments was acquired in this work through the study of the crystallinity of the samples. It is worth mentioning that although the method of Segal through XRD is still popular, it usually overestimates the value of the crystallinity index (CrI), exceeding the cellulose content [29]. For that reason, other indices calculated from ATR-FTIR analysis were employed to evaluate the crystallinity value. First, the lateral order index (LOI) allows monitoring changes linked to crystalline and amorphous structures in the biomass, being related to the organization of cellulose and directly proportional to the crystallinity [27,30]. Secondly, the total crystallinity index (TCI) is linked to planes assigned to C-H and CH2 and their behaviors [26]. Finally, hydrogen bond intensity (HBI) is related to an increase in hydroxyl groups in the cellulose hydrogen bonding, promoting high values of HBI (less crystallinity), which occurs in processes where cellulose I converts to cellulose II, although a decrease in total % crystallinity is noted [30].

In this sense, LOI, HBI, and CrI showed the same tendency, increasing after sample preparation (W-CB and PreH), as can be seen in Table 1. The higher crystallinity observed in W-CB compared with untreated CB could be a consequence of the solubilization in water of other amorphous compounds such as free sugars, soluble lignin, or extracts [24], increasing the glucan fraction [5] and therefore the CrI from 19.90 to 44.90%. Likewise, Haykiri-Acma and Yaman [31] observed a reduction in CrI after water treatment; however, they commented on the unclear information about water effects on CrI. In addition, the same authors obtained an increment in LOI values in three studied biomasses after water treatment, following the same trend as this work, where the LOI value of CB increased after washing from 1.96 to 2.15, respectively.

Table 1.

Moisture (%) and crystallinity of the starting materials: raw CB, washed CB, and solid residue after prehydrolysis (PreH).

On the other hand, PreH achieved the highest CrI values (56.14%) due to the strong removal of the amorphous fractions corresponding to pentose carbohydrates like xylan and arabinan, as was mentioned in our previous work, obtaining a cellulose-rich material (39.56 ± 0.20% of glucans) [5]. Additionally, diluted acid pretreatment induces the formation of more stable allomorph cellulose Iβ from Iα cellulose (susceptible to hydrolysis under acidic conditions), diminishing the degree of polymerization (DP) and increasing crystallinity [32]. In this sense, Huong et al. [33] obtained an increase of around 12% in CrI after acid pretreatment of vetiver grass at 0.5% (v/v) H2SO4 for 60 min. In addition, Santos et al. [34] observed the same behavior in elephant grass plant leaves and stems after pretreatment at all concentrations of H2SO4 studied (5, 10, and 15%).

3.2. Influence of DES Pretreatment on Different Biomasses

To the best of our knowledge, no reports have been published so far on processing CB by washing or hydrolyzing with diluted acid prior to diluted ChCl/U pretreatment to increase the saccharification efficiency. According to our previous work [5], DES pretreatment using diluted ChCl/U was a suitable strategy to recover glucan and xylan fractions from CB, achieving percentages of delignification close to 40%. Therefore, this work evaluates the saccharification of different CRMs after the pretreatment with diluted ChCl/U (mild-neutral alkali DES). Additionally, CB substrates non-pretreated by DES were also enzymatically hydrolyzed to compare the different strategies.

Even though the time of the DES pretreatment was set to 16 h in part I [5], the lower hemicellulose content and higher crystallinity presented by the PreH sample (Table 1) because of previous diluted acid pretreatment led to shorter treatment times with DES (4 and 8 h). In addition, DES acts mainly on hemicellulose and lignin [35], while cellulose only rearranges its structure due to DES action into intermolecular H-bonds, promoting the creation of new H-bonds between DES and hydroxyl groups of cellulose [36]. Particularly, this kind of DES can preserve the hemicellulose fraction of CB to a great extent (70–85%) as demonstrated in our previous work [5]. In this sense, as can be seen in Table 2, DES pretreatments carried out on PreH material offered delignification values around 27–28%, which were considerably lower than using DES in untreated CB (39.74 ± 2.40%). DES pretreatment on CB or only washed with water (W-CB) poorly removed the hemicellulose, retaining in great measure the total polysaccharide content up to 70%. While glucan content after DES pretreatment in PreH material achieved values between 47 and 50%, it was higher at longer pretreatment times.

Table 2.

Characterization of PreH solids before and after DES pretreatments and CB and W-CB after DES pretreatments at 16 h. All DES pretreatments were carried out at 100 °C and an LSR of 20:1 (w/w).

Table 2 also shows the crystallinity parameters obtained after DES pretreatment of samples. It can be seen that CB and W-CB after DES pretreatment increased their crystallinity, as indicated by CrI and TCI values compared with the starting materials.

However, this trend was only followed for LOI values in the case of W-CB+DES (from 2.15 to 2.62). Meanwhile, HBI showed the opposite tendency, decreasing crystallinity in three materials (CB, W-CB, and PreH) after DES pretreatment. Furthermore, it can be highlighted that PreH biomass subjected to different time pretreatments with DES showed similar behavior for all crystallinity indexes, increasing from 4 to 8 h and then decreasing again at 16 h. Excessively harsh conditions could promote the destruction of some cellulose crystalline areas [37], and cleavage of hydrogen bonds of biomass [38], which probably explains the reduction in crystallinity from 8 to 16 h. Additionally, the differences found in terms of crystallinity could be supported by the changes observed in ATR-FTIR and SEM analyses further explained.

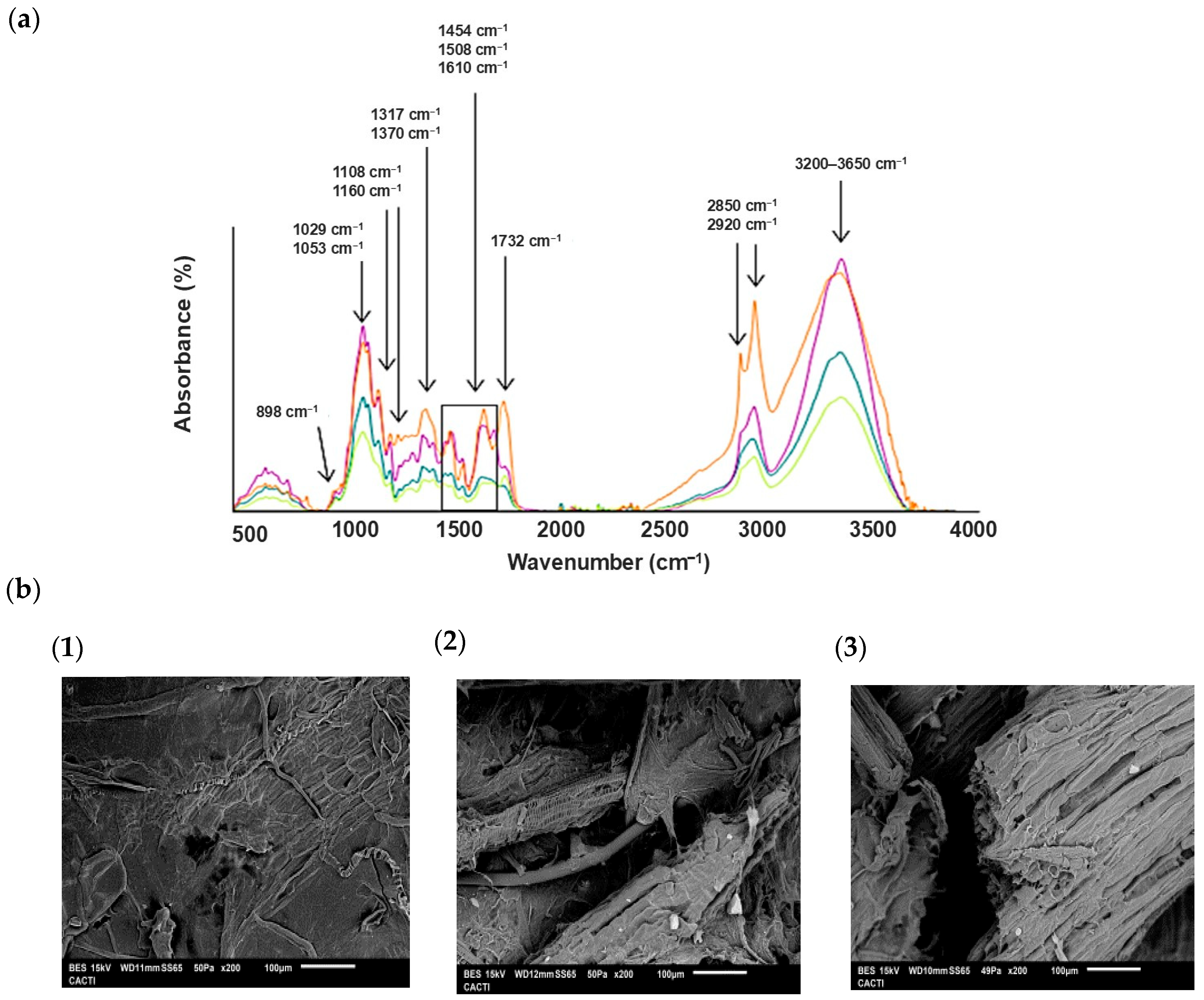

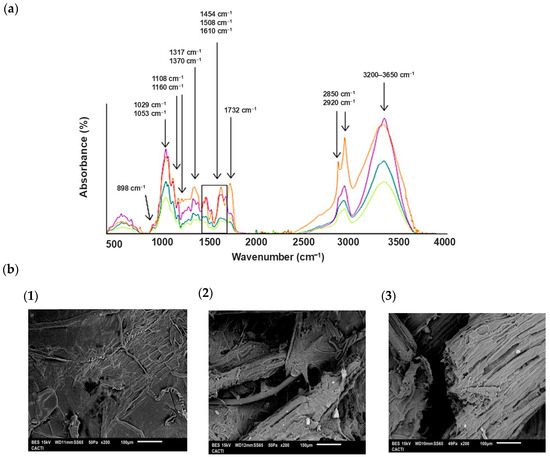

In order to understand the influence of time in DES pretreatment on PreH material, since their chemical composition was very similar (see above in Table 2), ATR-FTIR spectra are presented in Figure 1a. The spectra showed some similarities between PreH and PreH+DES at 8 h. Accordingly, the spectra remained quite similar in the 3125–3600 cm−1 band corresponding to OH free and hydrogen-bonded stretching of cellulose and cellulose derivatives [39], at 1029 cm−1 corresponding to C–H plane deformation and C–O stretching in cellulose and lignin [5], supporting cellulose retention caused by DES pretreatment. Conversely, characteristic peaks of lignin were decreased after DES pretreatment in PreH in bands 1610 cm−1 (C=O corresponding to stretching of aromatic ring in lignin and in carboxylic groups, carboxylic acid, and ester compounds) [40], 1108 cm−1 (aromatic deformation of lignin C–H), 1160 cm−1 (C–O–C stretching of cellulose and hemicellulose [26], and 2850 cm−1 and 2920 cm−1 (related to aromatic methoxyl groups stretching C−H and in methyl and methylene groups of side chains) [41], what is in concordance with delignification reported in Table 2. Moreover, it was also demonstrated that the effect of DES pretreatment at 8 h, observing lower intensities than PreH in feature peak at 1317 cm−1, linked to stretching C–O of substituted aromatic units [26] and 1732 cm−1 which can be attributed to lignin (off-plane C–H vibration in p-hydroxyphenyl units) [42], indicating the bonds of lignin-carbohydrate complexes and proving partial lignin removal of the PreH biomass as was previously reported. DES pretreatment at 4 and 16 h showed spectra with lower intensities than PreH, suggesting the remarkable impact of DES on this biomass. However, SEM-photos in PreH+DES at 4 h (Figure 1b) exhibited minor alterations in its structure than PreH+DES at 8 and 16 h, in which great morphology changes were noticed, highlighting the great number of pores and rupture of fibrils across the biomass.

Figure 1.

(a) ATR-FTIR spectra of PreH (orange line) *, PreH+DES 4 h (blue line), PreH+DES 8 h (purple line), and PreH+DES 16 h (light green line), and (b) SEM images of PreH DES 4 h (1), PreH+DES 8 h (2), and PreH+DES 16 h (3) *. * Results from part I [5].

3.3. Enzymatic Hydrolysis

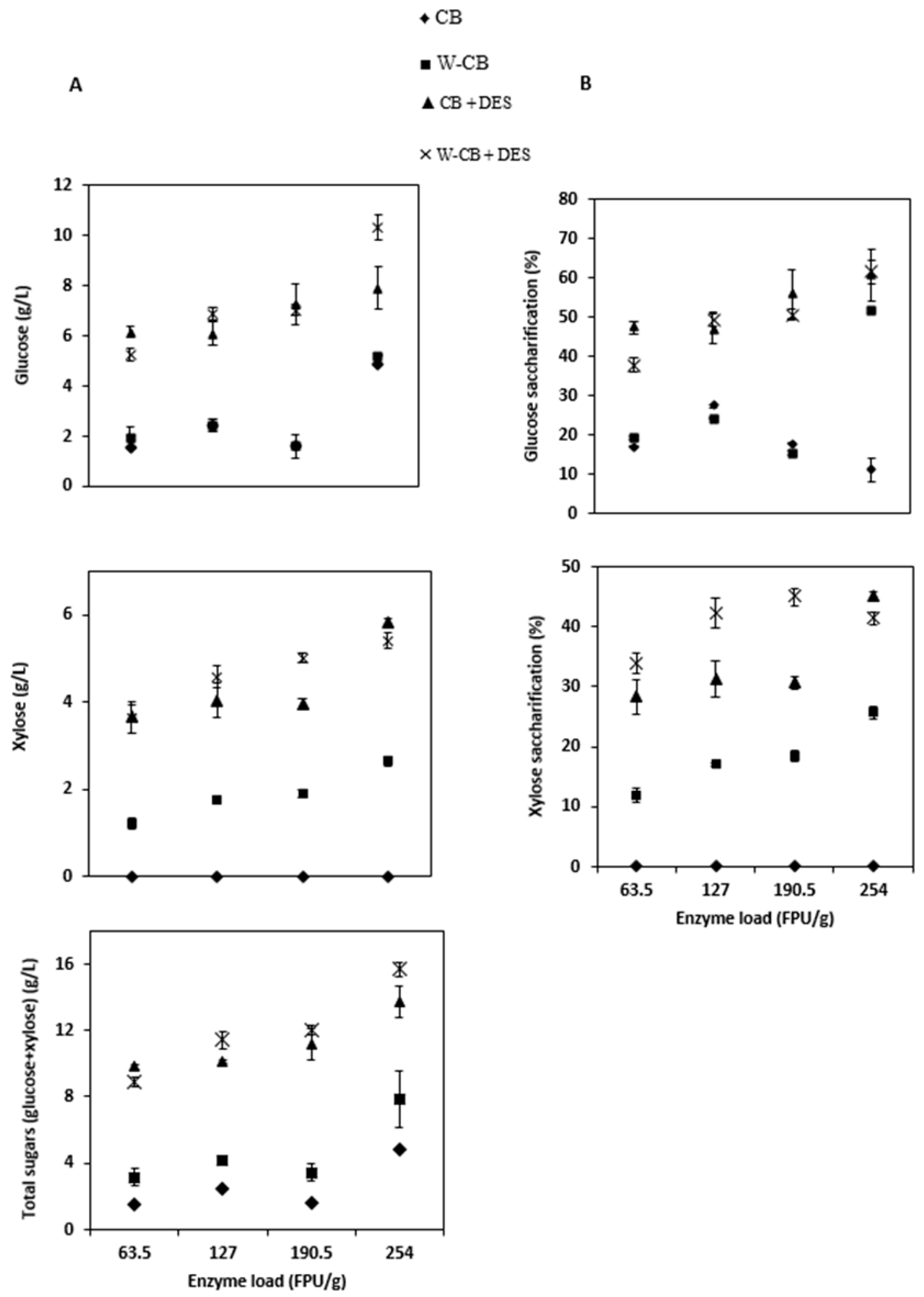

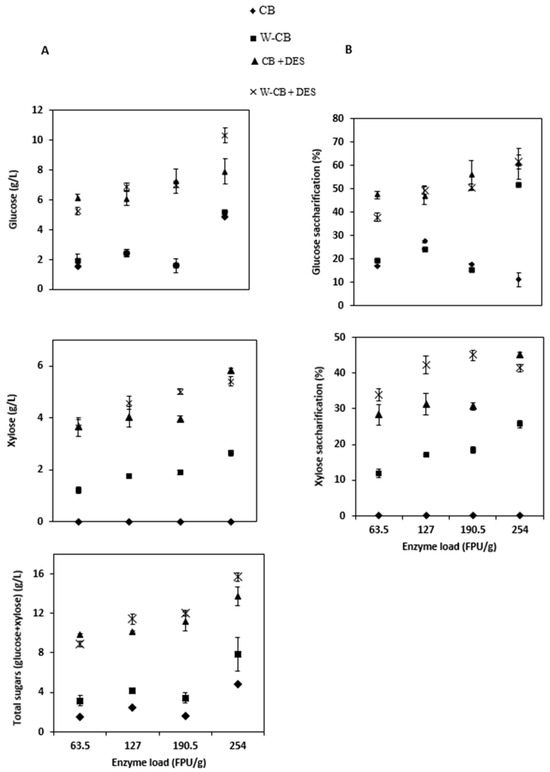

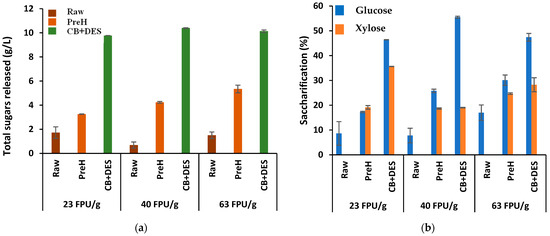

Enzymatic hydrolysis of CB, W-CB, and all CRMs obtained after pretreatment with ChCl/U was carried out for 72 h, assaying different enzyme loads because of the high total polysaccharide content. Released sugars (glucose, xylose, and total sugars) (Figure 2A) and glucose and xylose saccharifications (Figure 2B) were notably enhanced when ChCl/U pretreatment was carried out. In this sense, the enzymatic hydrolysis of CB and W-CB without DES pretreatment yielded the worst percentages of saccharification and, therefore, low concentrations of released monomeric sugars. Under the highest concentrations of enzyme load, only 4.85 and 7.83 g/L were released from CB and W-CB, respectively. However, after DES pretreatment, CB+DES and W-CB+DES showed the best percentages of total released sugars at maximum enzyme load, reaching more than 12 g/L. The same trend was followed by the attending glucose and xylose saccharifications, achieving around 60% and 40%, respectively, in both residues.

Figure 2.

Study of enzyme dosage in enzymatic hydrolysis of CB, W-CB, and all CRMs after DES pretreatment, (A) released glucose, xylose, and total sugars (g/L) and (B) glucose and xylose saccharification (%). Error bars correspond to n = 2.

Procentese et al. [43] achieved similar results of saccharification (58% of glucan and 31% of xylan) in corncob after ChCl/U pretreatment at 115 °C for 15 h of adding a high enzyme dosage (166 FPU/mL). Meanwhile, Pan et al. [44] reported similar saccharifications after all pretreatments with ChCl/U at conditions between 110 and 130 °C for 4 to 8 h, compared with the untreated rice straw using a low enzyme dosage of 89 μL of cellulase per gram. Therefore, an elevated amount of enzyme is necessary to obtain a reasonable sugar yield and release total sugars from CRMs after preparing CB with ChCl/U as it was reported in the literature and corroborated in this work. Nevertheless, recent works proved the suitability of using combined or sequential methods with this type of DES, observing better efficiencies in pretreatments [14,45]. Particularly, Ong et al. [46] reported higher sugar yields combining ultrasounds with NaOH-diluted ChCl/U in oil palm fronds. For that reason, an acid-diluted hydrolysis was postulated before DES pretreatment.

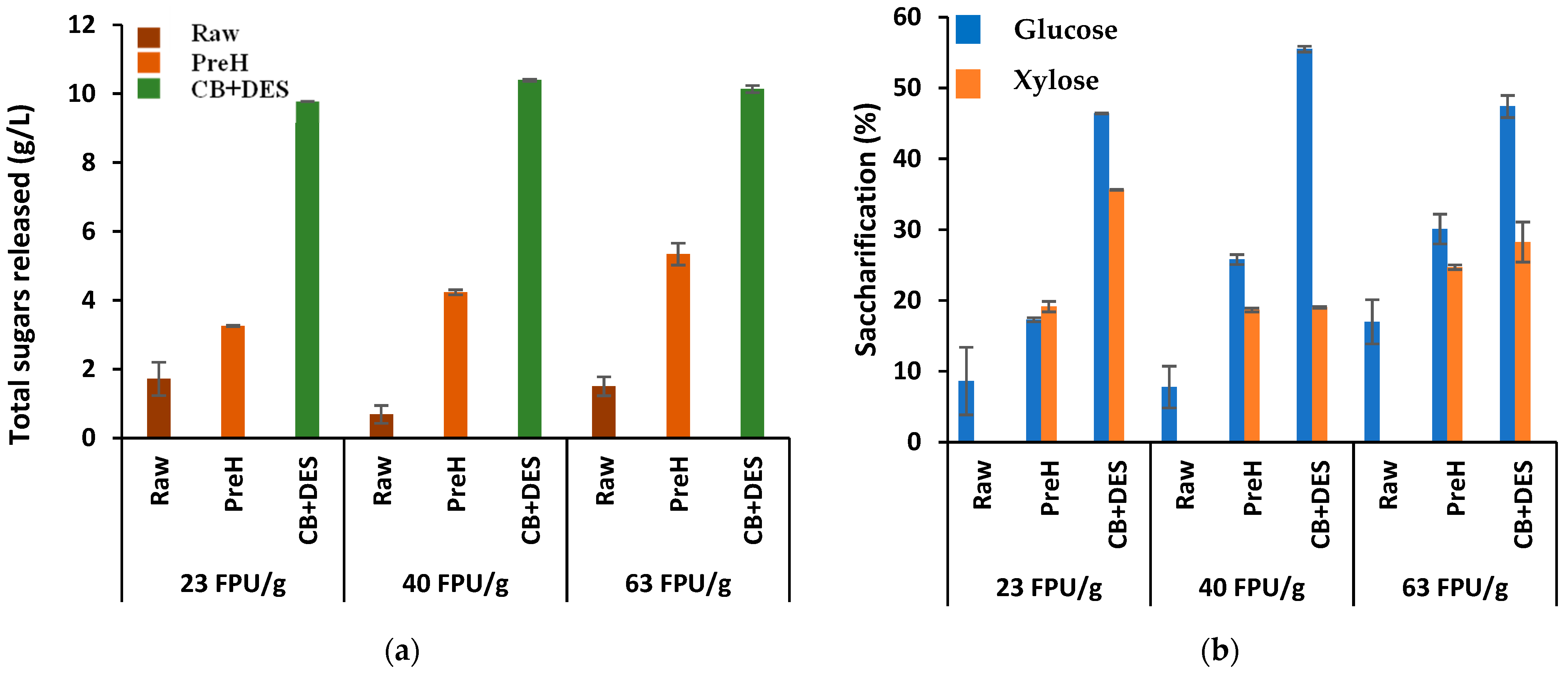

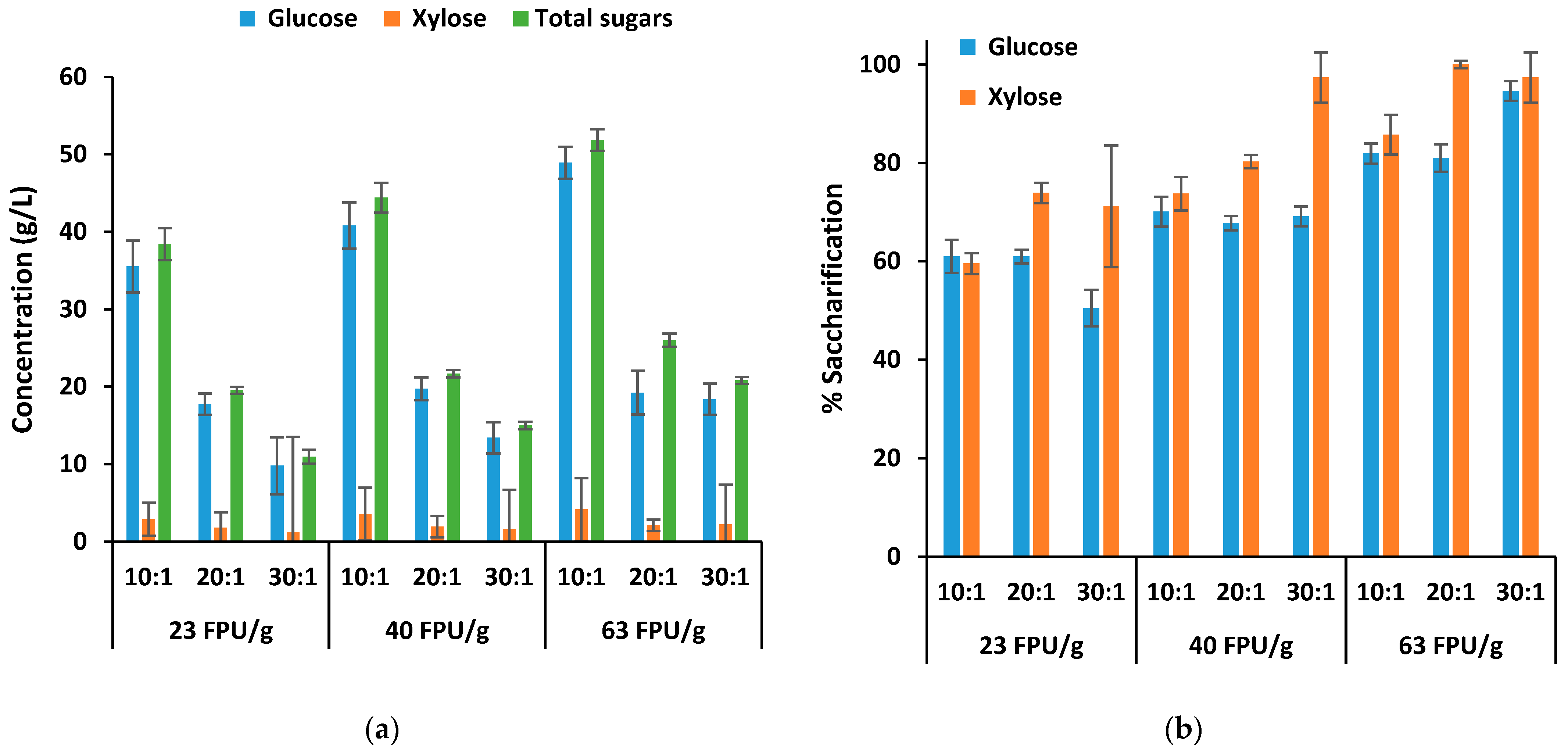

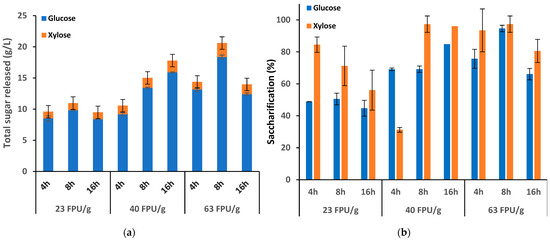

As other pretreatments were added to the process, lower amounts of enzyme (23, 40, and 63 FPU/g) were assayed in materials after sequential pretreatments (W-CB+DES, PreH+DES 4 h, PreH+DES 8 h, and PreH+DES 16 h) compared to prior enzymatic hydrolysis. In this sense, the initial three materials (CB, W-CB, and CB+DES) were also submitted to enzymatic hydrolysis under lower enzyme amounts to obtain comparative data (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Figure 3.

(a) Total sugar released during enzymatic hydrolysis and (b) saccharification percentage with lower dosage of enzyme (23, 40, and 63 FPU/g) of CB, PreH, and CRMs after DES pretreatments. DES pretreatments were conducted at 100 °C, 16 h, and LSR of 20:1 (w/w). Error bars correspond to n = 2.

Figure 4.

(a) Total sugar released during enzymatic hydrolysis and (b) saccharification percentage with lower dosages of enzyme (23, 40, and 63 FPU/g) of PreH + DES pretreatments at different times. All DES pretreatments were conducted at 100 °C and LSR of 30:1 (w/w). Error bars correspond to n = 2.

The results of total sugar released in CB+DES showed the same trend independently of the quantity of enzyme, with around 10 g/L (Figure 3a). However, PreH achieved higher concentrations of sugars as the quantity of enzyme added increased, reaching half (5 g/L) of that of DES pretreatment at 63 FPU/g. This fact corroborated the effectiveness of DES pretreatment to enhance enzymatic hydrolysis compared to conventional pretreatments such as diluted acid. Additionally, this advantage was confirmed in Figure 3b, which showed enzymatic saccharification percentages in the same three materials, achieving similar results to those previously described. Thus, DES pretreatment raised higher saccharifications than other materials at any enzyme charge studied. Particularly, glucose saccharification in CB+DES surpassed 50%, more than double that of PreH; meanwhile, xylose saccharification was around 18% for both materials, PreH and CB+DES, at 40 FPU/g. Thus, it was demonstrated the effectiveness and suitability of DES pretreatment compared to diluted acid hydrolysis in terms of saccharification. Zhang et al. [47] also confirmed the scarce performance in terms of sugars released after diluted acid hydrolysis on sunflower stalk bark using 1% of H2SO4 at 150 °C for 60 min, raising only 26% of glucose saccharification.

Sole DES pretreatment did not overstep 46% and 35% saccharification yields of glucose and xylose, respectively. However, sequential prehydrolysis and DES pretreatments showed the best saccharification yields at any time of DES pretreatment studied (Figure 4a). In this sense, PreH+DES 8 h achieved the best performance under any enzyme load studied. For instance, at intermediate enzyme load (40 FPU/g), release around 15 g/L of total sugars, corresponding with 70% of glucose and more than 95% of xylose saccharifications (Figure 4b). In this sense, Auxenfans et al. [48] also noted that sequential diluted acid and ionic liquid pretreatment improved saccharification yields compared to single pretreatments.

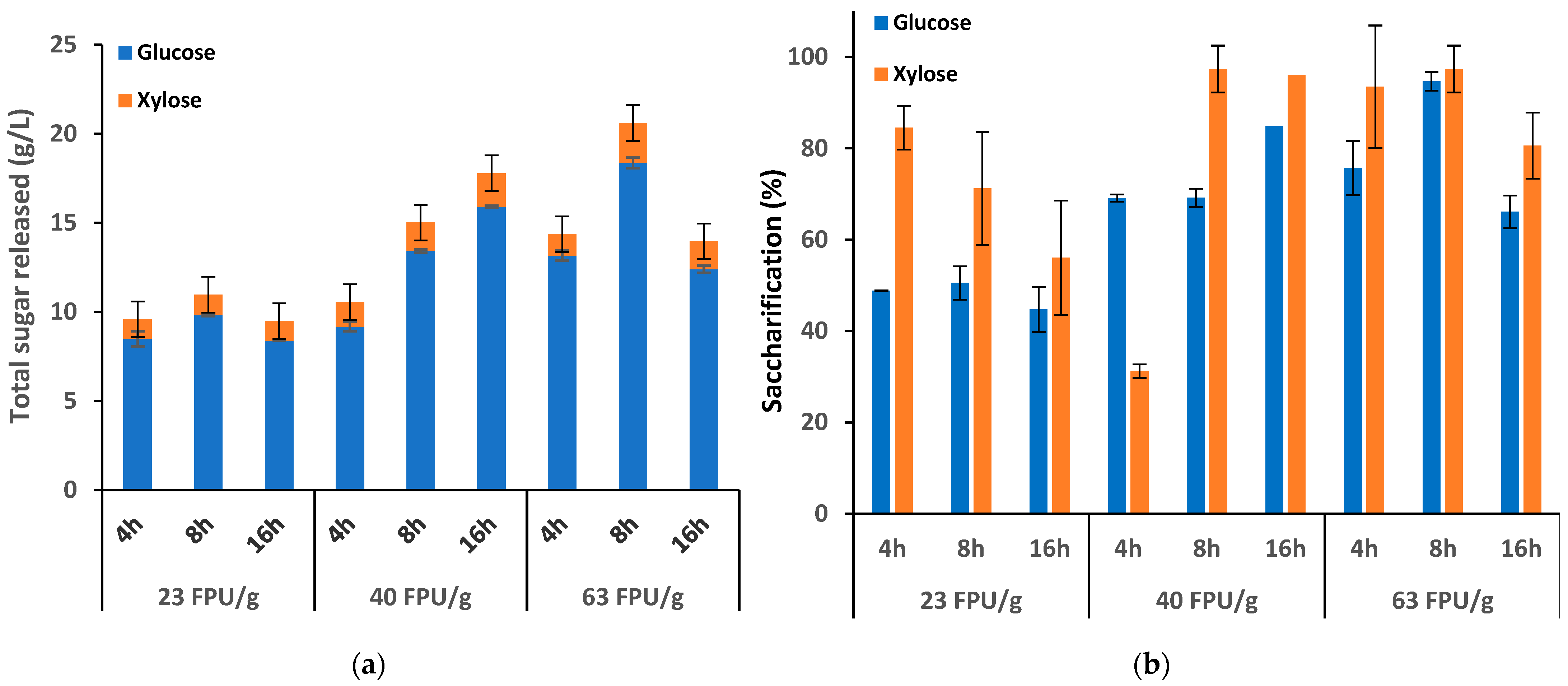

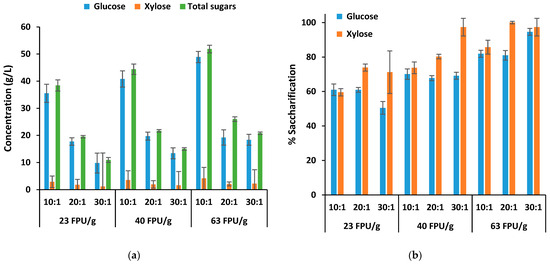

Figure 5 shows the sugar release (Figure 5a) and enzymatic saccharification (Figure 5b) of the best-performing material (PreH+DES 100 °C, 8 h) at different LSRs (10:1, 20:1, and 30:1).

Figure 5.

(a) Total sugar released during enzymatic hydrolysis and (b) saccharification percentages with lower dosages of enzymes (23, 40, and 63 FPU/g) at different LSR (10:1, 20:1, and 30:1) during enzymatic hydrolysis of PreH+DES pretreatments at 8 h, 100 °C, and LSR 20:1 (w/w). Error bars correspond to n = 2.

The results illustrated that when the enzyme load increases, maintaining the same LSR, the total sugars released also increase. This trend was observed for all LSRs assayed. For instance, at LSR 20:1, the total sugars increased from 19.55 g/L < 21.69 g/L < 26.01 g/L in ascending order of enzyme load (23 < 40 < 63 FPU/g). As expected, enzymatic saccharification also followed the same tendency previously mentioned; therefore, the best results were achieved at higher enzyme load using 63 FPU/g at LSR 30:1 (v/w) with 95% and 97% of glucose and xylose saccharifications, respectively. However, remarkable results were also attained at lower enzyme load (23 FPU/g) using LSR 20:1 (v/w) with 60.97% and 73.89% saccharification percentages of glucose and xylose.

These results clearly outperform those reported in previous works using ChCl/urea-based pretreatments for lignocellulosic biomass (see Table 3). While earlier studies on rice straw, wheat straw, and oil palm empty fruit bunches (OPEFB) achieved relatively modest saccharification yields—typically below 40% glucose and 20% xylose—even under severe pretreatment conditions (120–130 °C, 3–8 h) [44,49,50], the approach developed in this work reached up to 60% glucose and 74% xylose using mild temperatures (100 °C) during DES pretreatment and low enzyme load in enzymatic hydrolysis (23 FPU/g). This remarkable improvement can be attributed to the synergistic effect of the acid prehydrolysis step combined with diluted DES treatment, which significantly promotes hemicellulose solubilization in the first step and reduces biomass recalcitrance and structural disruption by the combination of both. Compared to alternative strategies such as ultrasound-assisted pretreatment (yielding only 35% glucose) [51], our approach demonstrates higher efficiency in releasing monomeric sugars. These findings highlight the potential of subsequent DES pretreatment to prehydrolysis solid residue as a promising route for enhancing enzymatic hydrolysis and biorefinery processes.

Table 3.

Comparative analysis on ChCl/urea as pretreatment in different biomasses and subsequent enzymatic hydrolysis to release monomeric sugars.

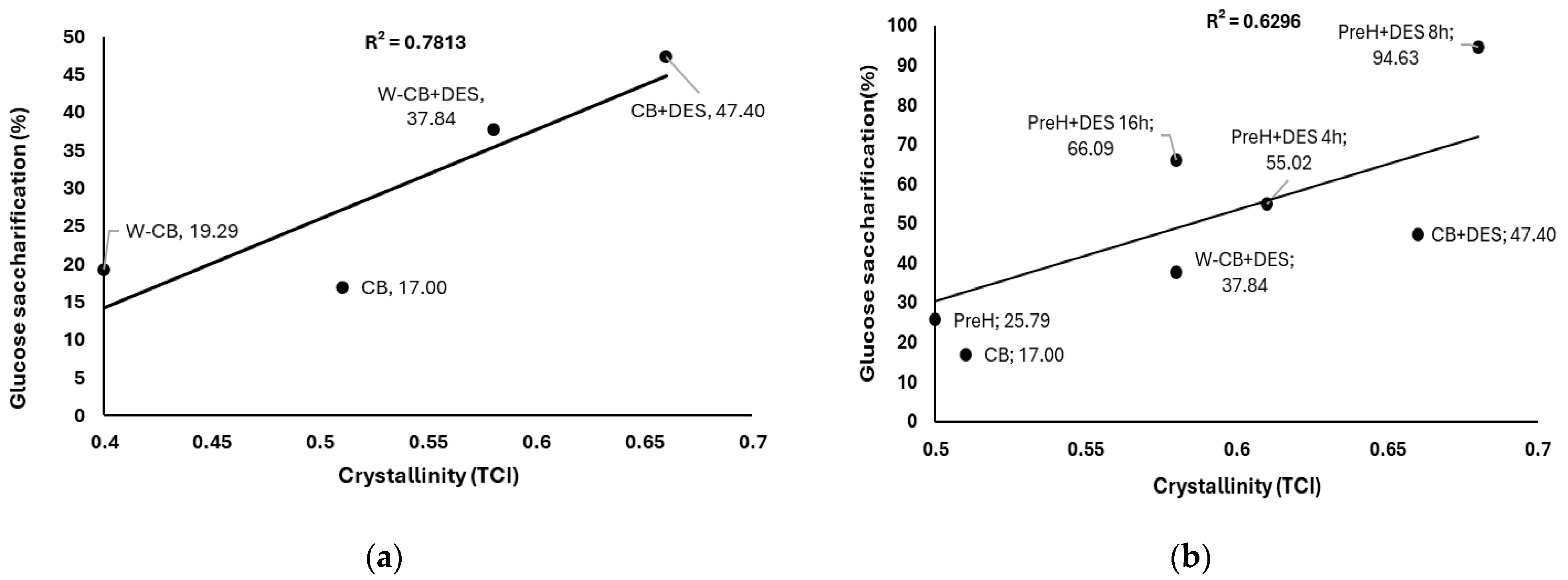

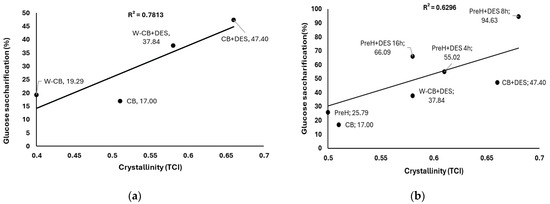

3.4. Relation Between Cellulose Crystallinity and Enzymatic Saccharification

Generally, the best results in saccharification of pretreated biomass were attributed to lower crystallinity values of pretreated biomass than raw biomass [53,54]. For instance, Kumar et al. [55] found that pretreatments commonly reduce crystallinity of biomass due to alterations in cellulose conformation. This fact could be explained by the disruption of cellulose microfibrils that decreases the cellulose polymerization degree, enhancing enzymatic digestibility [56]. However, we found in this study a positive trend between crystallinity and enzymatic saccharification, with saccharification generally enhanced as crystallinity increased. The TCI values, among all crystallinity parameters (LOI, CrI, and HBI), were the ones that fit best with saccharification results; they are represented in Figure 6. Thus, it was observed a value of R-square near 0.8 when TCI values of materials (CB, W-CB, CB+DES, and W-CB+DES) were correlated with their enzymatic saccharifications (Figure 6a). Meanwhile, when PreH+DES data was added, the R-square decreased to around 0.63. Several authors reported an increase in crystallinity, specifically after DES pretreatments [57,58,59]. For instance, Wang et al. [60] assayed four different polyol-based DES in mosso bamboo, noting a crystallinity change from 36.2% to nearly 70% and saccharification up to 80% after 48 h. Ong et al. [46] also observed higher crystallinity values after DES pretreatment with ultrasound-assisted ChCl/U in oil palm fronds, increasing CrI from 45.10% to 49.61%, although no improvements were observed in enzymatic saccharification, probably due to the short pretreatment time (30 min). However, Hou et al. [45] reported a two-fold improvement in cellulose digestibility and glucose yield when CrI values increased from 43.8% to 54.3% in rice straw compared to pretreated rice straw using ChCl/U for 12 h at 120 °C. This behavior could be explained by the retention of cellulose occurring due to the DES pretreatment and removal of amorphous fractions (lignin, hemicellulose, or amorphous cellulose), obtaining an increase in cellulose content of pretreated materials and, therefore, in crystallinity [61,62]. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that ChCl/U can produce nanofibrillation of bleached birch pulp at room temperature without changes in crystallinity and DP [63]. In addition, nanofibers are more susceptible to being hydrolyzed than lignocellulose [64] due to the increase in specific surface area and amorphous zones, which allows enzyme action and fast hydrolysis [65]. Additionally, Badillo et al. [66] also noticed slight swelling of cellulose using ChCl/U. For all these reasons, materials after DES pretreatment achieved better results in glucose saccharification than starting materials (CB, W-CB, and PreH), even having higher crystallinity values.

Figure 6.

(a) Relationship between glucose saccharification of CB, W-CB, CB+DES, and W-CB+DES at 63.5 FPU/g and their TCI values, and (b) Fit between glucose saccharification of CB, CB+DES, PreH, PreH+DES 4 h, PreH+DES 8 h, and PreH+DES 16 h at 40 FPU/g.

Finally, the effectiveness of ChCl/U as a post-prehydrolysis pretreatment was confirmed, as well as a substantial improvement in glucose saccharification yield while requiring a markedly lower enzyme dosage compared to either PreH alone or CB treated directly with DES. Likewise, a positive correlation was demonstrated between biomass crystallinity and enzymatic saccharification efficiency, suggesting that structural ordering plays a critical role in substrate accessibility and hydrolytic performance. This finding reinforces the importance of pretreatment strategies that modulate crystallinity to optimize sugar release.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the potential of chestnut burrs (CB) as a valuable feedstock for biorefinery applications through an environmentally friendly pretreatment strategy. The use of deep eutectic solvents (DES) composed of choline chloride and urea (ChCl/U, 1:2 mol/mol) effectively disrupted the lignocellulosic structure, enabling high saccharification yields after enzymatic hydrolysis. The best performance achieved up to 60% glucan and 74% xylan conversion under mild conditions (100 °C) of DES pretreatment in PreH material at 8 h, with further reduction in enzymatic hydrolysis parameters such as enzyme loading and LSR. These improvements significantly decrease pretreatment time from 16 h to 8 h, minimize energy consumption, and reduce the expenses of enzyme and buffer in the enzymatic hydrolysis step, enhancing both process efficiency and environmental sustainability. Overall, the proposed approach offers a promising pathway (prehydrolysis–DES–enzymatic hydrolysis) for the valorization of agro-industrial chestnut residues, contributing to the development of greener and more cost-effective biorefinery processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.C.-T., M.G.M.-A. and J.M.D.; methodology, I.C.-T. and M.G.M.-A.; software, I.C.-T. and M.G.M.-A.; validation, I.C.-T., M.G.M.-A., N.P.G. and J.M.D.; formal analysis, I.C.-T., M.G.M.-A. and J.M.D.; investigation, I.C.-T., M.G.M.-A. and J.M.D.; resources, N.P.G. and J.M.D.; data curation, I.C.-T. and M.G.M.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, I.C.-T. and M.G.M.-A.; writing—review and editing, N.P.G., R.P.d.S.O. and J.M.D.; visualization, I.C.-T. and M.G.M.-A.; supervision, N.P.G., R.P.d.S.O. and J.M.D.; project administration, J.M.D.; funding acquisition, J.M.D. and R.P.d.S.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (project PID2020-115879RB-I00), Xunta de Galicia of Spain (GRC-ED431C 2024/24), São Paulo Research Foundation FAPESP (processes n. 2018/25511-1 and n. 2023/09256-0) and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq, grant 304635/2025-1).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are also grateful to the Centro de Apoyo Científico y Tecnológico a la Investigación (CACTI), University of Vigo, for ATR-FTIR, XRD, and SEM analyses.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pino-Hernández, E.; Pinto, C.A.; Abrunhosa, L.; Teixeira, J.A.; Saraiva, J.A. Hydrothermal and High-Pressure Processing of Chestnuts—Dependence on the Storage Conditions. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 185, 111773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/apro_cpsh1__custom_19005194/default/table (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Andika, A.; Perdana, T.; Chaerani, D.; Utomo, D.S. Transitioning towards Zero Waste in the Agri-Food Supply Chain: A Review of Sustainable Circular Agri-Food Supply Chain. Sustain. Futur. 2025, 10, 100917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Trigo, I.; Otero-Penedo, P.; Outeiriño, D.; Paz, A.; Domínguez, J.M. Valorization of Chestnut (Castanea Sativa) Residues: Characterization of Different Materials and Optimization of the Acid-Hydrolysis of Chestnut Burrs for the Elaboration of Culture Broths. Waste Manag. 2019, 87, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Trigo, I.; Paz, A.; Morán-Aguilar, M.G.; Pérez Guerra, N.; Pinheiro de Souza Oliveira, R.; Domínguez, J.M. Enhancing the Biorefinery of Chestnut Burrs. Part I. Study of the Pretreatment with Choline Chloride Urea Diluted Deep Eutectic Solvent. Biomass Bioenergy 2023, 173, 106786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Jiang, X.; Shen, X.; Hu, J.; Tang, W.; Wu, X.; Ragauskas, A.; Jameel, H.; Meng, X.; Yong, Q. Lignin-Enzyme Interaction: A Roadblock for Efficient Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Lignocellulosics. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 154, 111822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, D.; Purkait, M.K. A Review on the Environment-Friendly Emerging Techniques for Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass: Mechanistic Insight and Advancements. Chemosphere 2021, 264, 128523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mankar, A.R.; Pandey, A.; Modak, A.; Pant, K.K. Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass: A Review on Recent Advances. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 334, 125235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashokkumar, V.; Venkatkarthick, R.; Jayashree, S.; Chuetor, S.; Dharmaraj, S.; Kumar, G.; Chen, W.H.; Ngamcharussrivichai, C. Recent Advances in Lignocellulosic Biomass for Biofuels and Value-Added Bioproducts—A Critical Review. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Gao, H.; Wang, Y.; He, B.; Lu, J.; Zhu, W.; Peng, L.; Wang, Y. Challenges and Perspectives of Green-like Lignocellulose Pretreatments Selectable for Low-Cost Biofuels and High-Value Bioproduction. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 369, 128315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Kong, Y.; Peng, J.; Song, X.; Liu, Y.; Su, Z.; Li, B. Comprehensive Analysis of Important Parameters of Choline Chloride-Based Deep Eutectic Solvent Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 319, 124209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.G.; Gurgel, L.V.A.; Baffi, M.A.; Pasquini, D. Pretreatment of Sugarcane Bagasse Using Citric Acid and Its Use in Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Renew. Energy 2020, 157, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy Choudhury, A.K. 4-Introduction to Enzymes. In Sustainable Technologies for Fashion and Textiles; Woodhead Publishing Series in Textiles; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; ISBN 9780081028674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Gong, L.; Ma, C.; He, Y.C. Enhanced Enzymatic Saccharification of Sorghum Straw by Effective Delignification via Combined Pretreatment with Alkali Extraction and Deep Eutectic Solvent Soaking. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 340, 125695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, H.; Zhou, H. Hemicellulose Degradation: An Overlooked Issue in Acidic Deep Eutectic Solvents Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 187, 115335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procentese, A.; Rehmann, L. Fermentable Sugar Production from a Coffee Processing By-Product after Deep Eutectic Solvent Pretreatment. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2018, 4, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Peng, X.; Sun, S.; Wen, J.; Yuan, T. Short-Time Deep Eutectic Solvents Pretreatment Enhanced Production of Fermentable Sugars and Tailored Lignin Nanoparticles from Abaca. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 192, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Mao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, F. Integrated Biorefinery of Bamboo for Fermentable Sugars, Native-like Lignin, and Furfural Production by Novel Deep Eutectic Solvents Treatment. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 188, 115453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, X.; Li, D.; Zhang, J.; Nawaz, H.; You, T.; Xu, F. Highly-Efficient Pretreatment Using Alkaline Enhanced Aqueous Deep Eutectic Solvent to Unlock Poplar for High Yield of Fermentable Sugars: Synergistic Removal of Lignin and Mannan. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 351, 126993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, K.A.; Sadeghi, R. Physicochemical Properties of Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Review. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 360, 119524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loow, Y.; Yeong, T.; Hoa, G.; Yang, L.; Kein, E.; Fong, L.; Jahim, J.; Wahab, A.; Hui, W. Deep Eutectic Solvent and Inorganic Salt Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Improving Xylose Recovery. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 249, 818–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morán-Aguilar, M.G.; Calderón-Santoyo, M.; de Souza Oliveira, R.P.; Aguilar-Uscanga, M.G.; Domínguez, J.M. Deconstructing Sugarcane Bagasse Lignocellulose by Acid-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents to Enhance Enzymatic Digestibility. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 298, 120097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Trigo, I.; Paz, A.; Otero-penedo, P.; Outeiriño, D.; Pinheiro, R.; Oliveira, D.S.; Manuel, J. Detoxification of Chestnut Burrs Hydrolyzates to Produce Biomolecules. Biochem. Eng. J. 2020, 159, 107599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Trigo, I.; Paz, A.; Otero-Penedo, P.; Outeiriño, D.; Pérez Guerra, N.; Domínguez, J.M. Enhancing the Saccharification of Pretreated Chestnut Burrs to Produce Bacteriocins. J. Biotechnol. 2021, 329, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluiter, A.; Hames, B.; Ruiz, R.; Scarlata, C.; Sluiter, J.; Templeton, D.; Crocker, D. Determination of Structural Carbohydrates and Lignin in Biomass. In Biomass Analysis Technology Team Laboratory Analytical Procedure; Determination of Structural Carbohydrates and Lignin in Biomass: Laboratory Analytical Procedure (LAP) (Revised July 2011); National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Applewood, CO, USA, 2011; pp. 1–14. Available online: https://docs.nrel.gov/docs/gen/fy13/42618.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Azizan, A.; Jusri, N.A.A.; Azmi, I.S.; Abd Rahman, M.F.; Ibrahim, N.; Jalil, R. Emerging Lignocellulosic Ionic Liquid Biomass Pretreatment Criteria/Strategy of Optimization and Recycling Short Review with Infrared Spectroscopy Analytical Know-How. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 63, S359–S367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poletto, M.; Júnior Ornaghi, H.L.; Zattera, A.J. Native Cellulose: Structure, Characterization and Thermal Properties. Materials 2014, 7, 6105–6119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, L.; Creely, J.J.; Martin, A.E.; Conrad, C.M. Empirical Method for Estimating the Degree of Crystallinity of Native Cellulose Using the X-Ray Diffractometer. Text. Res. J. 1958, 29, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, R.; Liu, G.; Cheng, G. Understanding Changes in Cellulose Crystalline Structure of Lignocellulosic Biomass during Ionic Liquid Pretreatment by XRD. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 151, 402–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kljun, A.; Benians, T.A.S.; Goubet, F.; Meulewaeter, F.; Knox, J.P.; Blackburn, R.S. Comparative Analysis of Crystallinity Changes in Cellulose i Polymers Using ATR-FTIR, X-Ray Diffraction, and Carbohydrate-Binding Module Probes. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 4121–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haykiri Acma, H.; Yaman, S. Treating Lignocellulosic Biomass with Dilute Solutions at Ambient Temperature: Effects on Cellulose Crystallinity. Biomass Convers. Biorefin 2022, 14, 9967–9981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.J.; Cao, S.L.; Lin, L.; Luo, X.L.; Hu, H.C.; Chen, L.H.; Huang, L.L. Hydrothermal Pretreatment of Bamboo and Cellulose Degradation. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 148, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huong, V.T.T.; Atjayutpokin, T.; Chinwatpaiboon, P.; Smith, S.M.; Boonyuen, S.; Luengnaruemitchai, A. Two-Stage Acid-Alkali Pretreatment of Vetiver Grass to Enhance the Subsequent Sugar Release by Cellulase Digestion. Renew. Energy 2022, 195, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.C.; de Souza, W.; Sant Anna, C.; Brienzo, M. Elephant Grass Leaves Have Lower Recalcitrance to Acid Pretreatment than Stems, with Higher Potential for Ethanol Production. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 111, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.K.; Li, H.; Lin, X.C.; Tang, L.; Chen, J.J.; Mo, J.W.; Yu, R.S.; Shen, X.J. Novel Recyclable Deep Eutectic Solvent Boost Biomass Pretreatment for Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 307, 123237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Tsai, M.L.; Chen, C.W.; Sun, P.P.; Patel, A.K.; Singhania, R.R.; Nargotra, P.; Dong, C. Di Deep Eutectic Solvents as Promising Pretreatment Agents for Sustainable Lignocellulosic Biorefineries: A Review. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 360, 127631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Li, A.; Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Chen, K. Efficient and Sustainable Fractionation of Eucalyptus Biomass into High Quality Cellulose and Lignin Using a Novel Ternary Deep Eutectic Solvent. Chem. Engin J. 2025, 518, 164829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.J.; Wen, J.L.; Mei, Q.Q.; Chen, X.; Sun, D.; Yuan, T.Q.; Sun, R.C. Facile Fractionation of Lignocelluloses by Biomass-Derived Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) Pretreatment for Cellulose Enzymatic Hydrolysis and Lignin Valorization. Green. Chem. 2019, 21, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morán-Aguilar, M.G.; Costa-Trigo, I.; Calderón-Santoyo, M.; Aguilar-Uscanga, M.G.; Pinheiro de Souza Oliveira, R.; Domínguez, J.M. Enhancing the Biorefinery of Brewery Spent Grain by Deep Eutectic Solvent Pretreatment: Optimisation of Polysaccharide Enrichment through a Response Surface Methodology. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2025, 145, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, G.; Maceratesi, V.; Leoni, E.; Stipa, P.; Laudadio, E.; Sabbatini, S. FTIR Spectroscopy for Determination of the Raw Materials Used in Wood Pellet Production. Fuel 2022, 313, 123017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suopajärvi, T.; Ricci, P.; Karvonen, V.; Ottolina, G.; Liimatainen, H. Acidic and Alkaline Deep Eutectic Solvents in Delignification and Nanofibrillation of Corn Stalk, Wheat Straw, and Rapeseed Stem Residues. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2020, 145, 111956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilatto, S.; Marconcini, J.M.; Mattoso, L.H.C.; Farinas, C.S. Lignocellulose Nanocrystals from Sugarcane Straw. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2020, 157, 112938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procentese, A.; Johnson, E.; Orr, V.; Garruto Campanile, A.; Wood, J.A.; Marzocchella, A.; Rehmann, L. Deep Eutectic Solvent Pretreatment and Subsequent Saccharification of Corncob. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 192, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Zhao, G.; Ding, C.; Wu, B.; Lian, Z.; Lian, H. Physicochemical Transformation of Rice Straw after Pretreatment with a Deep Eutectic Solvent of Choline Chloride/Urea. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 176, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.D.; Feng, G.J.; Ye, M.; Huang, C.M.; Zhang, Y. Significantly Enhanced Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Rice Straw via a High-Performance Two-Stage Deep Eutectic Solvents Synergistic Pretreatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 238, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, V.Z.; Wu, T.Y.; Chu, K.K.L.; Sun, W.Y.; Shak, K.P.Y. A Combined Pretreatment with Ultrasound-Assisted Alkaline Solution and Aqueous Deep Eutectic Solvent for Enhancing Delignification and Enzymatic Hydrolysis from Oil Palm Fronds. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 160, 112974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Cheng, L.; Zhou, X.; Ouyang, S. Comparative Evaluation of Dilute Acid, Alkaline, and Deep Eutectic Solvent Pretreatments on Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Sunflower Stalk Bark. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2025, 197, 5774–5789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auxenfans, T.; Buchoux, S.; Husson, E.; Sarazin, C. Efficient Enzymatic Saccharification of Miscanthus: Energy-Saving by Combining Dilute Acid and Ionic Liquid Pretreatments. Biomass Bioenergy 2014, 62, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi, S.; Lee, K.M. Comparison of Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) on Pretreatment of Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunch (OPEFB): Cellulose Digestibility, Structural and Morphology Changes. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 282, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Yu, G.; Wang, J. Comparative Insight into Biomass Pretreatment by Choline Chloride-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents in Relation to Their Physicochemical Characteristics. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.M.; Quek, J.D.; Tey, W.Y.; Lim, S.; Kang, H.S.; Quen, L.K.; Mahmood, W.A.W.; Jamaludin, S.I.S.; Teng, K.H.; Khoo, K.S. Biomass Valorization by Integrating Ultrasonication and Deep Eutectic Solvents: Delignification, Cellulose Digestibility and Solvent Reuse. Biochem. Eng. J. 2022, 187, 108587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panakkal, E.J.; Cheng, Y.-S.; Kuan-Shiong, K.; Pau-Loke, S.; Tantayotai, P.; Sriariyanun, M. Bioconversion of Napier Grass to 2-Phenylethanol: Unveiling the Synergy of Pretreatment with Deep Eutectic Solvents and Yeasts. Int. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. 2024, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, G.; Han, L.; Gao, C.; Xiao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Y. Quantitative Approaches for Illustrating Correlations among the Mechanical Fragmentation Scales, Crystallinity and Enzymatic Hydrolysis Glucose Yield of Rice Straw. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 241, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Che, X.; Ding, Y.; Kong, Y.; Li, B.; Tian, W. Effect of Crystallinity on Pretreatment and Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Lignocellulosic Biomass Based on Multivariate Analysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 279, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Muley, P.D.; Boldor, D.; Coty, G.G.; Lynam, J.G. Pretreatment of Waste Biomass in Deep Eutectic Solvents: Conductive Heating versus Microwave Heating. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 142, 111865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Z.; Guo, Z.; Huang, C.; Yao, L.; Xu, F. Deconstruction of Oriented Crystalline Cellulose by Novel Levulinic Acid Based Deep Eutectic Solvents Pretreatment for Improved Enzymatic Accessibility. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 305, 123025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Lv, M.; Cai, S.; Tian, X. Effects of Enzymatic Hydrolysis and Physicochemical Properties of Lignocellulose Waste through Different Choline Based Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) Pretreatment. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2023, 195, 116435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, J.P.; Metre, A.V.; Bhakhar, M.S.; Vetal, A.S. Comparative Study of Alkaline, Acidic, and Deep Eutectic Solvent Pretreatments on Lignocellulosic Biomass for Enhanced Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Biomass Convers. Biorefin 2025, 15, 14619–14631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udayakumar, V.; Anguraj, B.L. Optimized Deep Eutectic Solvent Cocktail Assisted Sequential Pretreatment to Enhance Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Arachis Hypogaea L Biomass. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation 2026, 206, 106207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, T.; Yao, S.; Tang, Y. Comparison of Polyol-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) on Pretreatment of Moso Bamboo (Phyllostachys Pubescens) for Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 189, 115767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundupalli, M.P.; Tantayotai, P.; Panakkal, E.J.; Chuetor, S.; Kirdponpattara, S.; Thomas, A.S.S.; Sharma, B.K.; Sriariyanun, M. Hydrothermal Pretreatment Optimization and Deep Eutectic Solvent Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass: An Integrated Approach. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2022, 17, 100957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.J.; Yang, J.Y.; Li, M.F.; Peng, F.; Bian, J. Efficient Fractionation of Woody Biomass Hemicelluloses Using Cholinium Amino Acids-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents and Their Aqueous Mixtures. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 354, 127139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirviö, J.A.; Visanko, M.; Liimatainen, H. Deep Eutectic Solvent System Based on Choline Chloride-Urea as a Pre-Treatment for Nanofibrillation of Wood Cellulose. Green. Chem. 2015, 17, 3401–3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Guerrero, L.; Silva-Mendoza, J.; Sepúlveda-Guzmán, S.; Medina-Aguirre, N.A.; Vazquez-Rodriguez, S.; Cantú-Cárdenas, M.E.; García-Gómez, N.A. Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Cellulose Nanoplatelets as a Source of Sugars with the Concomitant Production of Cellulose Nanofibrils. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 210, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahola, S.; Turon, X.; Österberg, M.; Laine, J.; Rojas, O.J. Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Native Cellulose Nanofibrils and Other Cellulose Model Films: Effect of Surface Structure. Langmuir 2008, 24, 11592–11599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Badillo, J.A.; Gallo, M.; Rutiaga-Quiñones, J.G.; Garza, J.; López-Albarrán, P. Insights on the Cellulose Pretreatment at Room Temperature by Choline-Chloride-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents: An Atomistic Study. Cellulose 2022, 29, 6517–6548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).