Abstract

Bedding angles (BAs) in coal mining promote shear failure and can trigger rockbursts. Using Particle Flow Code (PFC) direct shear simulations on coal with BA = 0°, 30°, 60°, and 90°, we quantified BA effects on mechanical behavior and cracking. Increasing BA reduces shear strength and shear modules, reaching minimum of 4 MPa and 0.7 GPa at 90°. Failure modes shift from progressive, bedding parallel shearing at 0° to mixed paths at 30–60°, and abrupt brittle failure at 90°. Crack density and orientation evolve systematically: dense bedding parallel shear at 0°; more dispersed, lower-density mixed shear tension at 30–60°; and reconcentrated, high-density cracking causing premature shear at 90°. Corresponding force chain patterns aligned at 0°, dispersed at 30–60°, and realigned at 90° govern these outcomes by modulating stress transfer across bedding interfaces. Overall, BA is the first-order control on coal shear instability; the quantified thresholds and mechanisms provide actionable guidance for excavation orientation, support design, and targeted monitoring to reduce shear out and rockburst risks in coal mines.

1. Introduction

Rockburst is a typical dynamic disaster threatening the safe mining of coal mines. Its nature lies in the sudden and violent release of elastic strain energy accumulated in the coal mass, resulting in the violent ejection and severe damage of the coal mass [1,2,3,4]. Furthermore, as a typical stratified sedimentary rock, the inherent bedding structure within the coal mass serves as the fundamental basis for controlling its mechanical anisotropy. This bedding structure significantly weakens the shear strength of the coal mass, thereby becoming a decisive factor in triggering structural instability. Research indicates that when roadway surrounding rock is subjected to loading at specific bedding plane orientations, it is highly prone to direct shear slip along structural planes, thereby inducing rockburst [5,6,7,8]. Intense coal mine rockbursts frequently cause severe damage to roadways and destruction of equipment, resulting in casualties and significant economic losses. Therefore, studying the influence of Bedding angles (BAs) on the mechanical behavior and fracture mechanism of coal samples holds crucial theoretical value and engineering practical significance for revealing the mechanism of rockburst disasters and formulating prevention and control strategies.

Scholars have adopted diverse research methodologies to investigate the mechanical behavior of coal-rock masses with varying BAs. Specifically, Li et al. [9] performed uniaxial compression tests and digital image correlation (DIC) measurements on double-layer composite rock specimens with multiple inclination angles under different bedding conditions. Their study analyzed the impacts of joint angles and BAs on crack evolution characteristics and the transformation of failure modes. Additionally, Hao et al. [10] conducted uniaxial and triaxial compression tests on slate specimens, encompassing 7 BA configurations and 5 confining pressure levels, thereby quantifying the regulatory effects of BAs and confining pressure on the brittle properties and mechanical behavior of slate. Previous studies have predominantly focused on the influence of BAs on the strength, deformation, and failure characteristics of coal under uniaxial [11,12], conventional triaxial [13], and true triaxial [14] loading conditions. However, there is a relative scarcity of literature systematically investigating the effect of BAs under direct shear (a specific loading path highly relevant to the triggering mechanism of rockbursts). The direct inducement of rockbursts lies in shear instability, yet the understanding of shear mechanical behavior under the sole influence of BAs remains insufficient.

As an effective method for investigating the influence of BAs on the mechanical behavior of coal samples, direct shear tests have been widely adopted by scholars worldwide. For instance, Zhang et al. [15] conducted a series of direct shear tests on cubic Longmaxi shale samples with seven different BAs and explored the anisotropic shear failure process from internal microcracking to surface macroscopic fracture using acoustic emission (AE) and DIC monitoring techniques. Fan et al. [16] carried out direct shear tests on shale samples with three typical BAs. By combining AE, DIC, and computed tomography (CT) technologies, they comprehensively investigated the anisotropy of shear mechanical properties and failure characteristics of each sample from external to internal aspects. Zhai et al. [17] applied direct shear tests to rock samples with artificially prefabricated fractures, examining the energy evolution process prior to sliding instability under complex shear loading paths with constant normal loads. Mashhadiali et al. [18] employed triaxial and direct shear tests, proposing an analytical model for predicting the shear strength of anisotropic rocks with different BAs using direct shear test data, and verified the accuracy of the model. The above analysis indicates that fruitful achievements have been made in research on the influence of BAs on the shear mechanical behavior of coal and rock masses. However, the mesoscopic mechanical mechanisms governing the effect of BAs on coal samples still require in-depth elucidation.

With the rapid advancement of computer technology, numerical simulation has been widely adopted across various fields as an economical and reproducible method [19]. PFC code is favored by scholars worldwide due to its unique advantages in simulating the fracture process of rock-like materials and revealing mesoscopic mechanical mechanisms. It can intuitively demonstrate particle-scale contact forces, crack initiation, energy conversion, and other phenomena. For example, Fan et al. [20] conducted a series of direct shear tests on shale with different BAs based on PFC. They investigated the evolution and distribution of microcracks, the three-dimensional anisotropy of shear strength parameters, and the influence of bedding plane stiffness. Song et al. [21] established a three-dimensional numerical model using PFC3D, focusing on the effects of confining pressure and BA on the failure behavior of composite rocks. Some scholars have also adopted a combined approach of laboratory tests and numerical simulations to study the influence of BAs on the mechanical behavior of coal. For example, Wang et al. [22] conducted experimental and numerical investigations on the effect of joint geometric parameters of rock masses on the anisotropy of shear behavior using PFC2D. They studied the complex interactions between joints and rock bridges at different scales. Gao et al. [23] performed laboratory direct shear tests and PFC2D numerical simulations on jointed rocks, conducting qualitative and quantitative analyses of the influence of roughness on the shear strength parameters of rock joints. However, existing studies on simulating the shear behavior of coal using PFC often simplify or fail to accurately characterize the layered structural features of coal, particularly the systematic influence of BAs. There are relatively few specialized studies on the refined simulation of the entire direct shear process under the influence of BAs without the interference of joints. Additionally, the evolution of force chain networks at the particle scale, as well as the laws governing crack distribution and propagation, remains insufficiently explored and revealed.

This work is distinct from prior DEM and laboratory studies that primarily focused on uniaxial/triaxial loading or coupled variables. We isolate BA under a direct shear path and provide a meso-to-macro linkage by jointly quantifying force chain fabric anisotropy and crack orientation statistics. The results lead to BA-specific, actionable recommendations for rockburst control, thereby bridging numerical insights and engineering practice.

Therefore, based on the PFC numerical simulation tool, a numerical model for direct shear tests of coal samples with different BAs was established. This study explores the shear stress-displacement relationships, strength, failure modes, microcrack evolution characteristics, and force chain features of coal samples under varying BAs. From both macroscopic and microscopic perspectives, it investigates the influence mechanism of BAs on the damage and crack propagation of coal samples, thereby revealing their impact on rock bursts.

2. Numerical Simulation Scheme

The Discrete Element Method (DEM) has emerged as a powerful tool for studying the mechanical behavior of materials such as rocks and concrete, thanks to its unique capability to analyze the deformation, damage, and failure processes of heterogeneous materials at the micro/mesoscopic scale. It can precisely simulate key mechanisms including particle contacts, force chain evolution, and energy dissipation, and has thus been widely adopted in both academic and engineering fields [24,25]. Among these, PFC 7.0 stands out as it can effectively reproduce damage phenomena such as crack initiation, propagation, coalescence, and particle breakage within materials. By tracking particle interactions, it reveals the intrinsic causes of macroscopic mechanical responses. Widely applied in fields including deep rock mass engineering, slope stability analysis, and soil-rock mixture research, PFC 7.0 provides an important numerical tool for understanding the engineering behavior of complex geological materials.

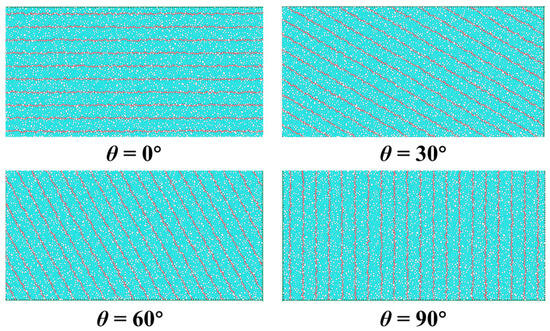

The numerical model in this study has a dimension of 200 mm × 100 mm, with particle sizes uniformly distributed in the range of 0.3–0.5 mm. Each complete numerical sample is discretized into 8266 particles, and the global damping coefficient is set to 0.1. Particle contacts adhere to the parallel bonding constitutive model. By referring to the PFC 7.0 contact selection method in the paper by Yang et al. [26], a discrete fracture network is invoked to locate nodes and install a smooth joint model. Finally, numerical models of coal samples with BAs of 0°, 30°, 60°, and 90° are constructed, with bedding distributed throughout the entire model, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

DEM modeling of coal with different BAs (0°, 30°, 60°, 90°).

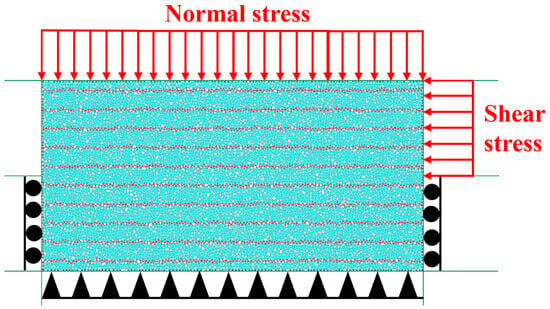

The numerical model parameters in this study are verified through reference [24], and the micromechanical parameters in the parallel bonding model are finally determined, as listed in Table 1. The model boundary conditions are illustrated in Figure 2: upper, lower, left, and right walls of the shear box are set, where the lower wall is fixed; a normal stress of 1 MPa is applied to the upper wall; the left and right walls are divided into two parts from the middle, with the lower parts allowed to roll vertically only, the upper-left part remaining free, and a shear stress of 1 MPa applied to the upper-right part. The test terminates when the shear displacement reaches 4 mm, and the mechanical behaviors of coal samples with different BAs are recorded. The shear displacement termination (4 mm) corresponds to δ/W = 0.02 (2%) for the present specimen width (W = 200 mm).

Table 1.

Values of microscopic parameters in numerical simulation.

Figure 2.

Boundary conditions of the shear model.

3. Result Analysis and Discussion

3.1. Characteristics of Shear Stress-Displacement Curves

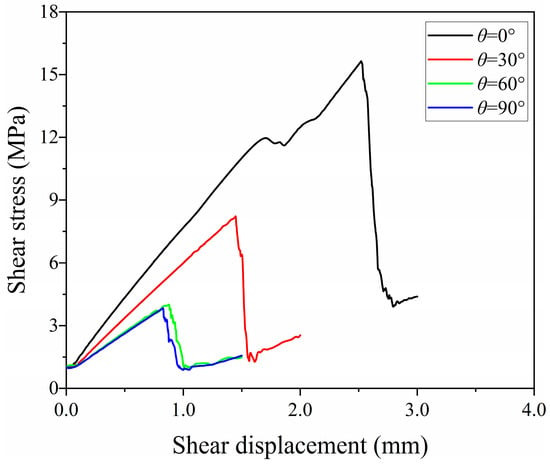

Through direct shear tests on the established numerical model, the process before the first peak point in the shearing process was selected as the research object of this study. The shear stress-displacement curves of specimens with different BAs were obtained, as shown in Figure 3. It can be seen from Figure 3 that all shear stress-displacement curves with different BAs exhibit a stage of “rising-peaking-declining (stabilizing)”, corresponding to the process of elastic deformation, damage evolution, and eventual failure of the coal. The differences in deformation of coal samples with different BAs are as follows:

Figure 3.

Stress-displacement curves of coal samples with different BAs (0°, 30°, 60°, 90°).

θ = 0° (bedding parallel to the shear plane): The curve shows a long rising segment and a high peak, indicating that the coal requires greater displacement to accumulate damage. After failure, the stress drops but maintains a certain residual strength. This reflects that when the bedding is parallel to the shear plane, the resistance to shear sliding between particles is high, and the failure mode is dominated by inter-particle dislocation within the bedding plane and matrix shearing.

θ = 30°/60° (bedding obliquely intersecting the shear plane): Both the peak stress and residual strength decrease, and the curve fluctuates more obviously (e.g., θ = 30°). This indicates that when the bedding obliquely intersects the shear plane, cracks tend to initiate and propagate along the intersection area of the bedding plane and shear plane, resulting in more scattered damage and a complex failure mode.

θ = 90° (bedding perpendicular to the shear plane): The peak stress is the lowest, and after failure, the stress drops rapidly to nearly zero. This reflects that when the bedding is perpendicular to the shear plane, the shear force easily directly breaks the connection between the bedding and the matrix, leading to rapid crack coalescence. The failure mode is dominated by bedding plane tensile cracking and matrix fragmentation, resulting in the weakest shear resistance of the coal.

In summary, the smaller the BA (i.e., the more parallel the bedding is to the shear plane), the higher the shear strength of the coal, and the coal samples tend to exhibit ductile failure. Conversely, the larger the BA (i.e., the more perpendicular the bedding is to the shear plane), the lower the shear strength, and the coal samples are dominated by brittle failure.

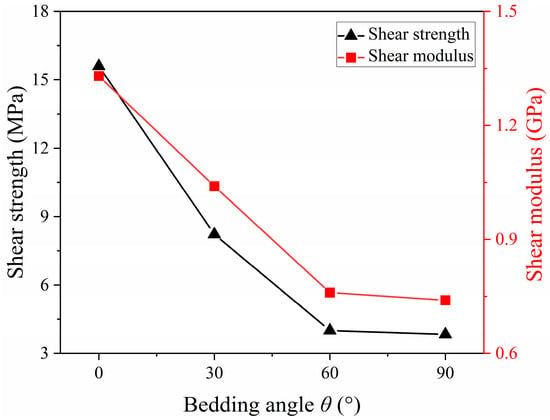

Taking the highest point of the shear stress-displacement curve as the shear strength of the coal sample and the slope of the elastic stage in the shear stress-displacement curve as the shear modulus of the coal sample, the evolution curves of mechanical parameters for coal samples with different BAs were plotted, as shown in Figure 4. It can be observed from Figure 4 that as the BA increases from 0°to 90°, both the shear strength and shear modulus show a significant downward trend, with the attenuation rate being fast in the early stage and tending to flatten in the later stage.

Figure 4.

Peak shear strength (triangles) and shear modulus (squares) versus BAs (0°, 30°, 60°, 90°). Strength and stiffness monotonically decrease with BA; the attenuation is rapid from 0° to 30° and levels off beyond 60°.

BAs significantly affect the peak shear strength of coal (represented by gray triangles). At θ = 0°, the peak stress is the highest (close to 16 MPa); at θ = 30°, it drops to 8 MPa; and at θ = 90°, it reaches the lowest value (approximately 4 MPa). This indicates that the angle between bedding and the shear direction directly alters the shear resistance of coal, with substantial differences between the “shear along bedding” and “shear across bedding” states.

Bedding planes are weak structural planes in coal, with their bonding strength being lower than that of the coal matrix. When the angle between the bedding and the shear plane varies, the stress state experienced by the bedding plane during the shearing process also differs. For instance, when the BA is 90°, the shear force can easily cause tensile failure of the bedding plane, and cracks propagate rapidly along the bedding plane, leading to a quick loss of the overall bearing capacity of the coal and a significant reduction in the peak shear strength. When the bedding obliquely intersects the shear plane, however, the shear force will generate varying degrees of stress concentration in the bedding plane and the matrix, promoting easier initiation and propagation of microcracks at their junction, which in turn affects the peak shear strength of the coal.

BAs significantly influence the shear modulus of coal (represented by red squares). At θ = 0°, the shear modulus is approximately 1.5 GPa; at θ = 30°, it drops to 1.0 GPa; and at θ = 90°, it approaches 0.7 GPa, with a decrease of over 50%. This indicates that BAs can alter the stiffness characteristics of coal samples. Coal samples sheared parallel to the bedding exhibit higher stiffness, making them less prone to shear failure, while those sheared perpendicular to the bedding are more susceptible to stiffness weakening. As the BA changes, internal damage in coal evolves from local and minor to large-scale and multi-scale damage accumulation, leading to a “sudden” deterioration in macroscopic mechanical parameters (such as shear modulus). This also provides macroscopic mechanical response evidence for subsequent analysis of the influence of BAs at the mesoscopic level (e.g., particle contact force distribution, crack evolution paths). In summary, the larger the BA, the weaker the shear resistance and stiffness of the coal.

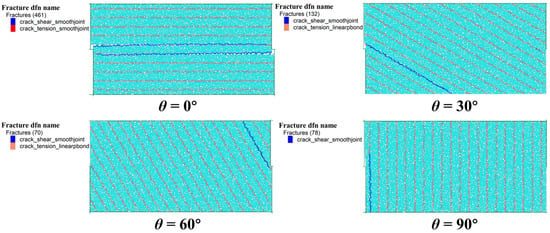

3.2. Failure Mode

To further analyze the influence of BAs on the failure mode of coal samples from a microscopic perspective, the post-processing module of PFC code was used to plot the failure modes of coal samples, as shown in Figure 5 (where red represents shear cracks in smooth joints, blue represents tensile cracks in smooth joints, and orange represents tensile cracks in the matrix). When θ = 0° (bedding parallel to the shear plane), cracks are distributed in horizontal bands and extend along the bedding plane (blue cracks). This is because when the bedding is parallel to the shear plane, shear forces easily cause particle sliding within the bedding plane and damage to the weak connections between beddings, making cracks preferentially initiate and propagate along the bedding plane, thus exhibiting the characteristic of “shear failure along the bedding”.

Figure 5.

Failure mode of coal samples with different BAs (0°, 30°, 60°, 90°). The blue cylinders represent shear cracks generated by the smooth joint model, the red cylinders represent tensile cracks generated by the smooth joint model, and the orange cylinders represent tensile cracks generated by the linear contact model.

When θ = 30°, cracks exhibit an obliquely penetrating pattern, including both sliding cracks along the bedding plane (blue) and cross-bedding tensile/shear cracks. With the bedding obliquely intersecting the shear plane, shear forces act on both the bedding plane and the matrix simultaneously, causing cracks to easily initiate at the intersection of the bedding and matrix. This forms an “oblique coalescing failure” and results in a more complex failure path.

When θ = 60°, cracks remain obliquely distributed but show stronger coalescence, propagating along the resultant direction of the bedding and shear directions. As the BA increases, the shear component borne by the matrix rises, making cracks more prone to cross-bedding propagation. Consequently, the failure mode shifts to a “matrix-dominated and bedding-assisted” pattern.

When θ = 90°, cracks are distributed vertically or nearly vertically, extending longitudinally along the bedding plane. With the bedding perpendicular to the shear plane, the shear force directly severs the connection between the bedding and the matrix, causing cracks to rapidly tensilely propagate and coalesce along the bedding plane. This exhibits the characteristic of “tensile-shear failure perpendicular to bedding” and results in a more concentrated failure surface.

Combined with the previous changes in shear stress-displacement curves and mechanical parameters, the mesoscopic crack distribution can explain the macroscopic mechanical responses. At θ = 0°, cracks extend along the bedding plane, and the failure is progressive and ductile, corresponding to high peak strength and high shear modulus. At θ = 90°, cracks coalesce rapidly, and the failure is sudden and brittle, corresponding to low peak strength and low shear modulus. When θ is an oblique angle (30° or 60°), cracks coalesce in a complex manner, and the failure mode lies between the two extremes, with the macroscopic performance showing a gradual attenuation of strength and modulus.

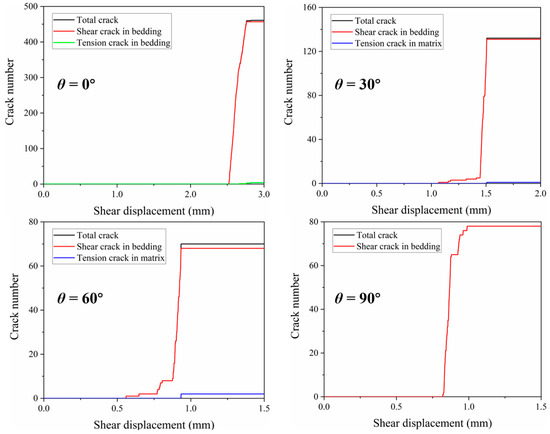

3.3. Evolution Characteristics of Microcracks

To quantitatively describe the distinct evolution characteristics of cracks in coal samples with different BAs during loading, the evolution laws of various types of cracks and their strains were plotted, as shown in Figure 6. It can be seen from Figure 6 that BAs significantly affect the microcrack evolution characteristics of coal during direct shearing. At θ = 0°, shear cracks on the bedding plane dominate the microcrack evolution. Before the shear displacement reaches approximately 2.5 mm, the number of tensile cracks on the bedding plane is extremely small. When the shear displacement approaches 2.5 mm, the number of shear cracks on the bedding plane increases sharply, and the total number of cracks is mainly contributed by shear cracks on the bedding plane. This indicates that under the horizontal BA, the initial tensile failure of the coal sample is negligible, and the sample mainly undergoes shear failure along the bedding plane.

Figure 6.

Microfracture characteristics of coal samples from different bedding planes (BA = 0°, 30°, 60°, 90°). Black lines indicate total fractures, red lines denote shear fractures, and blue lines represent tensile fractures.

When θ = 30°, shear cracks on the bedding plane still play a dominant role. Before the shear displacement reaches approximately 1.2 mm, there are a small number of shear cracks on the bedding plane, and tensile cracks in the matrix are almost nonexistent. When the displacement exceeds 1.2 mm, the number of shear cracks on the bedding plane increases rapidly, and a small number of tensile cracks also appear in the matrix, though their quantity is far less than that of shear cracks on the bedding plane. This indicates that for coal samples with a 30° BA during shearing, failure is dominated by shear along the bedding plane, while a small amount of tensile failure in the matrix begins to occur simultaneously.

When θ = 60°, both the number of shear cracks on the bedding plane and tensile cracks in the matrix increase. Before the shear displacement reaches 0.8 mm, there are a small number of initial cracks. After 0.8 mm, the number of shear cracks on the bedding plane gradually increases, and tensile cracks in the matrix also show a certain growing trend, though shear cracks on the bedding plane still dominate in quantity. This indicates that when the BA increases to 60°, the failure mode of the coal sample becomes more complex, leading to both shear failure along the bedding plane and tensile failure in the matrix during shearing.

When θ = 90°, shear cracks on the bedding plane are the main form of cracks in the sample. Before the shear displacement reaches approximately 0.8 mm, there are almost no cracks. After that, the number of shear cracks on the bedding plane increases rapidly, while there is no obvious development of tensile cracks in the matrix (or their quantity is extremely small). This indicates that under the perpendicular BA, the crack propagation of the coal sample is similar to the case of θ = 0°: the sample mainly undergoes shear failure along the bedding plane, but the failure occurs at a smaller shear displacement.

In summary, BAs significantly influence the microcrack evolution characteristics associated with the direct shear mechanical properties of coal. At small angles (0° and 30°), failure is dominated by shear along the bedding plane, with little tensile failure occurring. At 60°, the failure mode becomes more complex, involving both shear along the bedding plane and the presence of tensile cracks in the matrix. At 90°, the failure pattern returns to being dominated by shear along the bedding plane, but with failure occurring earlier.

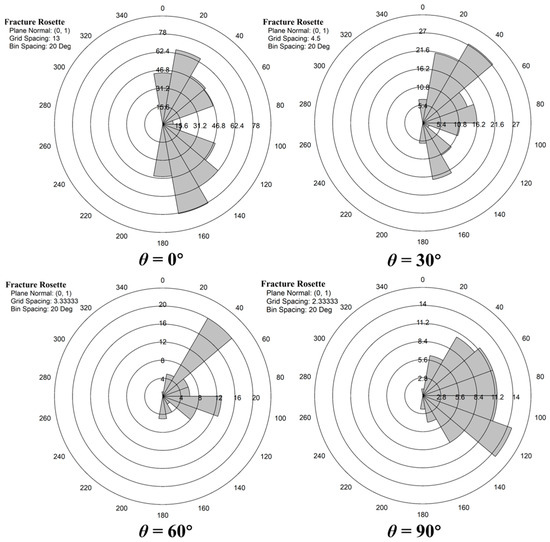

To further clarify the distribution characteristics of internal crack orientations in coal samples with different BAs, the orientations of cracks were obtained using the PFC post-processing program. Rose diagrams illustrating the trends of microcracks in damaged coal samples are presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Crack inclination distribution of coal samples with different BAs (0°, 30°, 60°, 90°).

As shown in Figure 7, when θ = 0°, microcracks are distributed in multiple angular directions in the polar coordinate plot, with the number of cracks in some directions (e.g., specific fan-shaped regions) being relatively concentrated and having larger values (such as 78, 62.4, etc.). At this point, the bedding is horizontal, and the coal is dominated by shear failure along the bedding plane, yet the polar coordinate plot shows a multi-directional crack distribution. This indicates that although shearing along the bedding is the main failure mode of the sample, due to the complex stress transmission during direct shearing, microcracks still initiate and propagate in different directions. It further reveals that during the failure of coal with horizontal bedding, cracks do not propagate entirely along a single bedding direction; instead, there exists a certain degree of dispersed multi-directional damage. When θ = 30°, the overall number of cracks is lower than that at θ = 0°, with a more scattered distribution across all angular directions and smaller peak values. At this angle, shear failure along the bedding plane coexists with a small amount of tensile failure in the matrix, which is reflected in the polar coordinate plot as a scattered, low-peak distribution. This indicates that as the failure mode becomes more complex, the concentration of cracks in specific directions weakens. Stress is no longer concentrated in a few directions parallel to the bedding; instead, the involvement of the matrix in the failure process leads to a more diversified range of crack directions.

When θ = 60°, the number of cracks further decreases, with an even sparser distribution, and the values across all directions are relatively close. Both shear failure along the bedding plane and tensile failure in the matrix are more pronounced, resulting in more uniform and dispersed damage in the coal. The rose diagram shows a uniform, low-quantity distribution, which reflects that under the complex failure mode, stress transmission across different directions is more balanced, with no obvious dominant crack direction, and multi-regional synchronous damage occurs in the coal. When θ = 90°, cracks show a relatively concentrated distribution in specific directions. Although the peak number of cracks is not as high as that at θ = 0°, it is more prominent compared to 30° and 60°. With shear failure along the bedding plane being dominant, the polar coordinate plot reflects this relatively concentrated distribution. This indicates that during the failure of coal with perpendicular bedding, crack directions exhibit a certain degree of concentration again. It reflects that when the BA is perpendicular, the damage direction of the coal is constrained by the bedding, leading to the re-emergence of a relatively concentrated direction of crack propagation.

Thus, by combining the evolution of microcrack quantity and the directional distribution in polar coordinates, it is found that changes in BAs not only affect the growth pattern of microcrack quantity but also significantly alter the directional distribution characteristics of cracks. At small BAs, the constraint of bedding leads to a concentrated direction of cracks with a large quantity. As the BA increases, the complex failure mode results in a dispersed direction of cracks and a decrease in their quantity. When the bedding is perpendicular, the constraint of bedding causes the direction of cracks to become relatively concentrated again. However, due to the change in bedding orientation, the concentrated direction differs.

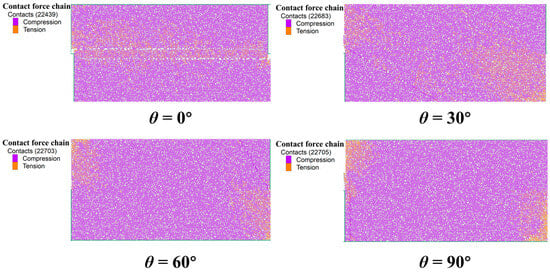

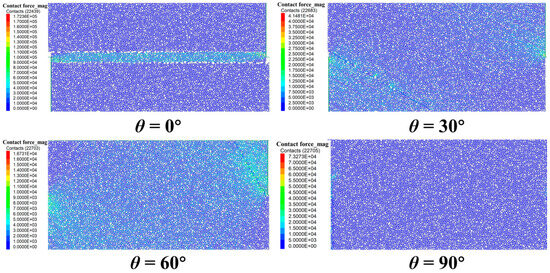

3.4. Characteristics of Force Chain

The distribution of force chains is an intuitive reflection of internal stress transmission in coal and is closely related to microcrack evolution. Building on the previous research on the quantity and directional distribution of microcracks, this section further reveals the mechanism by which BAs affect the direct shear mechanical response of coal by analyzing the characteristics of force chains (compression and tension) in coal under different BAs. The force chain characteristics of coal samples with different BAs are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Force chain attribute characterization of coal samples with different BAs (0°, 30°, 60°, 90°). The purple cylinders represent the compression contact force chain, while the red orange cylinders represent the compression contact force chain.

When θ = 0°, compressive force chains (purple) are widely and uniformly distributed in the coal, dominating overall stress transmission. Tensile force chains (orange) near the bedding plane are prominent, showing local concentration along the bedding. For coal with horizontal bedding under shear, tensile stress concentration on the bedding plane induces such tensile chains. The dominance of compressive chains reflects shear failure along the bedding: most stress is transmitted through compressive chains between upper and lower coal, while local tension from shear displacement on the bedding aligns with the dominance of bedding shear cracks. Force chain distribution controls microcrack initiation and propagation along and near the bedding. At θ = 30°, force chain distribution grows more complex, with compressive chains still dominant. Under combined bedding and loading effects, tensile chains expand in area and deviate slightly from the bedding direction. Corresponding to microcrack evolution, bedding shear coexists with minor matrix tensile failure here. This indicates θ = 30° alters stress transmission paths: bedding shear-induced stress disturbances spread to the matrix, triggering matrix tensile chains and cracks. The non-uniform, multi-directional force chains shift failure from single bedding shear to a bedding-matrix composite mode.

At θ = 60°, compressive force chains tend to distribute uniformly, while tensile chains increase in number and scatter across different regions of the coal without obvious concentrated directions. Both bedding shear and matrix tensile failure are significant here. The uniformization of force chains reflects more balanced internal stress transmission in the coal. As the bedding’s constraint on force chains weakens, tensile chains emerge in multiple regions due to stress concentration, driving synchronous and dispersed initiation of microcracks in both bedding and matrix. This embodies the coordinated and dispersed characteristics of force chain and microcrack evolution under a complex failure mode. At θ = 90°, compressive force chains concentrate in non-bedding regions. Tensile chains near bedding are less concentrated than at θ = 0° but align better with loading direction. Perpendicular bedding blocks and redistributes force chains: compressive chains bypass bedding for focused transmission, while shear-induced tensile chains are affected by vertical bedding orientation. Force chains drive rapid bedding microcrack propagation, matching earlier abrupt microcrack growth at small displacements, guiding early concentrated failure.

BAs dominate the initiation-propagation-connection process of microcracks by regulating force chain distribution. At small BAs, bedding constraints cause force chains to transmit concentratedly along the bedding, leading to local tensile stress on the bedding plane that generates numerous bedding shear cracks. As the angle increases, force chains exhibit dispersed and multi-directional characteristics, promoting composite propagation of microcracks in both bedding and matrix, thus complicating the failure mode. For perpendicular bedding, force chains reconcentrate, driving early shear failure of microcracks along the bedding plane. As stress transmission carriers, force chains interact with microcrack evolution. Microcrack propagation alters force chain paths, while force chain reconstruction guides the initiation of new cracks. The two synergistically respond to changes in BAs and jointly determine the direct shear mechanical properties of coal.

The size of force chains can reveal the damage degree of coal samples under external loads [27]. Therefore, evaluating the size of force chains in coal samples from a microscopic perspective is of great significance for understanding the macroscopic fracture mechanism of coal samples induced by the effect of BAs. Figure 9 shows the distribution diagrams of force chain sizes in coal samples with different BAs. At θ = 0°, the distribution of contact force chain sizes shows obvious stratification. Force chain sizes near the bedding plane concentrate in the medium to low range (blue-cyan) while those in the upper and lower coal regions are relatively higher (yellow-red). This makes the bedding plane prone to shear sliding weakening stress transmission here and resulting in smaller force chains on the bedding plane. The upper and lower coal mass bear the main load through compressive force chains leading to larger force chains there.

Figure 9.

Force chain magnitude characteristics of coal samples with different BAs (0°, 30°, 60°, 90°).

At θ = 30°, contact force chain magnitudes distribute more dispersedly, with reduced differences between bedding and matrix regions. Medium-to-low magnitude chains increase in proportion, while high-magnitude ones shrink and disperse. This reflects complex stress transmission paths due to combined bedding shear and matrix tension, preventing force chain concentration in single regions and reducing overall magnitudes. Such dispersion drives multi-regional microcrack propagation. At θ = 60°, contact force chains are dominated by medium-to-low magnitudes, with high-magnitude ones extremely rare and highly dispersed. This reflects more balanced internal stress transmission under θ = 60°, as weakened bedding constraints prevent high-strength force chain concentration. With relatively uniform stress borne synchronously across multiple coal regions, this aligns with dispersed microcrack initiation and propagation in both bedding and matrix. The low-magnitude, dispersed force chains support uniform damage under the complex failure mode. At θ = 90°, contact force chain magnitudes show local concentration: medium-to-high values appear in non-bedding regions, while those near bedding are relatively low. Under shear of perpendicular bedding, the bedding plane impedes stress transmission, making force chains bypass it to concentrate in other coal areas as localized high-magnitude chains. Shear sliding along bedding prevents high-strength chain accumulation there, and this local concentration drives rapid microcrack propagation and coalescence along the bedding.

The BA θ reshapes the magnitude spatial distribution of contact force chains, thereby governing stress transfer and damage evolution in coal: at θ = 0°, layered force chains create a “weak stress transfer zone” and layering shear/splitting dominates; at θ = 30°, more dispersed chains dilute local stress concentrations, producing mixed tensile shear failure; at θ = 60°, low magnitude, dispersed chains yield more uniform damage; at θ = 90°, locally concentrated chains trigger early bedding related failure. Force chain distribution thus serves as a quantitative indicator of stress transfer: high magnitude clusters nucleate/drive crack growth, while low magnitude zones exhibit delayed damage; together they coevolve with microcracks and ultimately control direct shear strength and deformation.

These patterns are jointly supported by three lines of evidence: acoustic emission tests [28] show high energy events clustering where strong chains concentrate, with declining b values signaling rapid crack propagation; PFC-DEM under uniaxial compression [29] yields a V-shaped strength θ relation with a minimum at 60° and force chain intensity/density that “decreases then increases,” consistent with more uniform damage; PFC-DEM in direct tension [30] demonstrates a one-to-one mapping between force chain guidance/force amplitudes and crack geometry across θ, highlighting bedding controlled, oriented failure at 60°. Together, they corroborate that force-chain–crack–failure-mode coupling is the physical backbone linking angle effects to strength and deformation.

Low BA (about 0–30°)—Progressive, bedding guided damage: prioritize bedding reinforcement (short encapsulation resin bolts and selective grouting that stitch the bedding interfaces), maintain higher normal confinement via dense surface support (mesh + shotcrete), and track bedding parallel micro slip/AE activity as an early warning cue. Intermediate BA (about 30–60°)—Mixed-mode crack growth: adopt combined surface-plus-deep support (mesh/shotcrete + cable bolts crossing bedding), locally densify the pattern in the dominant crack-orientation sector, and implement routine convergence measurements to capture stiffness loss. High BA (about 60–90°)—Rapid brittle separation along weak planes: install continuous support bands oriented to clamp the weak plane, use high capacity/energy absorbing bolts or cables that cross bedding, and increase the frequency of AE and displacement monitoring to capture fast post-peak degradation.

To aid practical use, we also provide a concise workflow: (i) identify local BA from core/televiewer data, (ii) classify the heading into low/intermediate/high BA, (iii) select the corresponding support layout from the above guidance, and (iv) apply targeted monitoring with escalation rules for abnormal AE/displacement trends. These additions convert the discussion from general statements into concrete, field-applicable guidance directly informed by our results.

4. Conclusions

This study used PFC-based DEM direct shear simulations to isolate the effect of BA θ (0°, 30°, 60°, 90°) on the shear mechanical response and fracture mechanisms of coal. The key findings are:

- (1)

- Strength and stiffness decrease monotonically with θ. From θ = 0° to 90°, peak shear strength drops from 16 MPa to 4 MPa (about 75%), and shear modulus decreases from 1.5 GPa to 0.7 GPa (about 53%). The attenuation is rapid between 0° and 30° and then levels off toward 60–90°.

- (2)

- Failure modes transition from ductile to brittle as θ increases. At θ = 0°, cracks propagate progressively along bedding planes (ductile, bedding-parallel shear). At θ = 30–60°, mixed, transitional networks form with more complex paths. At θ = 90°, cracks penetrate rapidly and coalesce, producing abrupt brittle failure.

- (3)

- Microcrack evolution and orientations are angle dependent. Small θ promotes dense bedding-parallel shear cracks with limited matrix tension; at θ = 60°, matrix tensile activity and dispersed orientations increase; at θ = 90°, bedding-controlled shear failure initiates earlier and crack orientations reconcentrate.

- (4)

- Force chain distributions govern the observed meso-macro link. Small θ concentrates force chains along bedding, triggering bedding-parallel shear. Intermediate θ (30–60°) disperses and weakens force chains, driving mixed bedding matrix damage with more uniform stress transfer. At θ = 90°, force chains reconcentrate and promote early bedding-related failure. These mesoscopic patterns consistently explain the measured reductions in strength and stiffness and the shift in failure mode with θ.

Implication: BA alone controls direct shear instability pathways in coal; the quantified θ-dependent strength/stiffness and mesoscopic fabrics provide a mechanistic basis for θ-specific support and monitoring strategies in rockburst-prone settings.

This study examines only four discrete BAs (0°, 30°, 60°, 90°) within a PFC direct-shear framework, idealizes bedding geometry and material properties (excluding roughness, infill, and weak interlayers), and relies on non-unique micro-parameter calibration, which may affect the robustness of crack-evolution and force chain interpretations. The loading path is simplified to direct shear under a single normal stress without coupling confining pressure, rate/cyclic/dynamic effects, or thermo-hydro-mechanical interactions. In addition, the scale and boundary conditions of the numerical specimens differ from field situations, limiting external validity. Future work should cover continuous angles and more complex bedding configurations, incorporate bedding heterogeneity and multi-level confining/rate effects, and conduct multi-scale physical tests with in-situ data for systematic validation and refinement.

Future research will deepen discrete element simulations of coal’s direct shear behavior under BAs from three aspects:

First, introduce randomized mesoscopic parameter models (e.g., bedding roughness, interface anisotropy) combined with on-site data to enhance the accuracy of characterizing coal heterogeneity and engineering relevance. Second, expand coupled simulations of hydraulic, thermal effects and BAs to explore their dynamic regulation of shear strength, crack evolution and force chain features, supporting deep mine support design. Third, use discrete element-finite element coupling for cross-scale analysis to quantify BAs’ influence on shear instability warning thresholds, providing precise numerical tools for roadway stability control and rock burst prevention.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H. and J.O.; resources, J.O.; software, J.H.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H.; writing—review and editing, J.O., Y.T., X.H. and B.W.; funding acquisition, J.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2024YFC3015805).

Data Availability Statement

The related data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Jinhong Hu was employed by Pingdingshan Tian’an Coal Industry Co., Ltd. Author Xiaojun He was employed by Fangshan Xinjing of Pingyu Coal and Electricity Co., Ltd. Author Yanjun Tong was employed by Coal Mining and Utilization Research Institute, Pingdingshan Tian’an Coal Mining Co, Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Hu, J.; He, M.; Li, H.; Tao, Z.; Liu, D.; Cheng, T.; Peng, D. Rockburst hazard control using the excavation compensation method (ECM): A case study in the Qinling water conveyance tunnel. Engineering 2024, 34, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; He, M.; Cheng, T.; Qiao, Y.; Liu, D.; Hu, J.; Xiao, Y. Effects of intermediate principal stress on strainburst in granite: Insights from true-triaxial unloading experiments and PFC3D-GBM simulations. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; He, M.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, D.; Hu, J.; Cheng, T. Granite strainbursts induced by true triaxial transient unloading at different stress levels: Insights from excess energy ΔE. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2025, 17, 7078–7092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdag, S.; Karakus, M.; Nguyen, G.D.; Taheri, A.; Bruning, T. Evaluation of the propensity of strain burst in brittle granite based on post-peak energy analysis. Undergr. Space 2021, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; He, M.; Qiao, Y.; Cheng, T.; Han, Z. Assessing burst proneness and seismogenic process of anisotropic coal via the realistic energy release rate (RERR) index. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2024, 58, 2999–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.; Cai, M. Numerical modeling of rockburst near fault zones in deep tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 80, 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; He, M.; Qiao, Y.; Cheng, T.; Xiao, Y.; Gu, Z. Mode I fracture properties and energy partitioning of sandstone under coupled static-dynamic loading: Implications for rockburst. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2023, 127, 104025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askaripour, M.; Saeidi, A.; Rouleau, A.; Mercier-Langevin, P. Rockburst in underground excavations: A review of mechanism, classification, and prediction methods. Undergr. Space 2022, 7, 577–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lin, H.; Lin, Q.-B.; Wang, Y.-X.; Zhao, Y.-L.; Hu, H.-H. Mechanical behavior and failure characteristics of double-layer composite rock-like specimens with two coplanar joints under uniaxial loading. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2023, 33, 2815–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Wang, S.; Xu, Q.; Yang, D.; Zhang, Q.; Jin, D.; Wei, Y. Influences of confining pressure and bedding angles on the deformation, fracture and mechanical characteristics of slate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 243, 118255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; He, M.; Hu, J.; Wu, H.; Wang, W.; Ren, M. Mechanical and damage properties study of rocks with different joint inclinations under seepage-stress coupling: Insights based on energy theory. Comp. Part. Mech. 2025, 12, 2713–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Li, B.; Li, C.; Wu, B.; Wang, J. Research on anisotropic characteristics and energy damage evolution mechanism of bedding coal under uniaxial compression. Energy 2024, 301, 131659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Liu, J.; Xu, D.; Zhang, L.; Lyu, C.; Ren, Y. Investigation on Mechanical Properties, AE Characteristics, and Failure Modes of Longmaxi Formation Shale in Changning, Sichuan Basin, China. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2023, 56, 1239–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Peng, J.; Kwok, F.C.Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, L. Influence of Intermediate Principal Stress on Mechanical and Failure Properties of Anisotropic Sandstone. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2024, 57, 7795–7812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Zhang, R.; Lu, H.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, L. Anisotropy in shear failure of shale: An insight from microcracking to macrorupture. Measurement 2025, 243, 116391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Ren, L.; Xie, H. 3D anisotropy in shear failure of a typical shale. Pet. Sci. 2023, 20, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, M.; Bai, H.; Wu, L. Shear Slip Instability Behavior of Rock Fractures under Prepeak Tiered Cyclic Shear Loading. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 8851890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashhadiali, N.; Molaei, F. Theoretical and experimental investigation of a shear failure model for anisotropic rocks using direct shear test. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2023, 170, 105561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, F.; Furtney, J.; Damjanac, B. A review of methods, applications and limitations for incorporating fluid flow in the discrete element method. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2022, 14, 1005–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Nie, X.; Yao, Z.; Li, C.; Wang, J.; He, L.; Wang, M.; Ren, L. 3D anisotropic microcracking mechanisms of shale subjected to direct shear loading: A numerical insight. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2024, 298, 109950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Yang, S.-Q.; Li, K.-S.; Yin, P.-F.; Pan, P.-Z. Mechanical behavior and fracture evolution mechanism of composite rock under triaxial compression: Insights from three-dimensional DEM modeling. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2023, 56, 7673–7699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Ren, F.; Miao, S. Evaluation of the anisotropy and directionality of a jointed rock mass under numerical direct shear tests. Eng. Geol. 2017, 225, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Wang, S.; Yin, H.; Zhao, Q.; Vladimr, P.; Li, Y. Estimation of shear strength parameters considering joint roughness: A stability case analysis of bedding rock slopes in an Open-Pit Mine. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Chen, J.; Han, D.; Liu, Z.; Peng, K.; Li, J. Three-dimensional discrete element simulation of a transversely isotropic rock considering initial cracks. Comput. Geotech. 2025, 186, 107434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, G.; Zhou, J.; Ma, J.; Cai, X. Failure mechanism analysis of rock in particle discrete element method simulation based on moment tensors. Comput. Geotech. 2021, 136, 104215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-Q.; Yin, P.-F.; Li, B.; Yang, D.-S. Behavior of transversely isotropic shale observed in triaxial tests and Brazilian disc tests. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2020, 133, 104435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Z.; Qi, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Y. DEM investigation of strain behaviour and force chain evolution of gravel–sand mixtures subjected to cyclic loading. Particuology 2022, 68, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, W. Experimental Investigation of the Acoustic Emission and Energy Evolution of Bedded Coal under Uniaxial Compression. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.; Niu, J.; Wang, B.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, J.; Lyu, B.; Zhan, B.; Ma, Y. Numerical Simulation of Coal’s Mechanical Properties and Fracture Process under Uniaxial Compression: Dual Effects of Bedding Angle and Loading Rate. Processes 2024, 12, 2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, E.; Yue, J.; Miao, B.; Xi, D.; Teng, X. DEM Simulation Study on the Mechanical and Micro-Fracture Characteristics of Jointed Coal under Direct Tensile Conditions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 30812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).