1. Introduction

The main challenge in engineering and construction for resource exploitation is the need to address both complex geological conditions and a changing external environment. These issues typically arise from intricate interactions among multiple variables and their prevalent nonlinear relationships [

1,

2]. For instance, in geotechnical engineering, the inherent uncertainty and spatial variability of geological conditions can directly impact the project’s initial design, construction safety, and subsequent maintenance [

3,

4]. In mining engineering, blasting is a necessary operation for efficient and economical production in mining [

5]. The intensity of vibrations is influenced by numerous parameters from the source to the propagation path [

6,

7]. Even minor prediction errors in vibration can cause structural damage or lead to legal disputes, making it particularly crucial to accurately predict and pre-emptively control the intensity and impact range of blasting vibrations [

8]. Traditional solutions, including empirical methods, field testing, and numerical analysis, all have inherent limitations [

9]. Empirical methods are limited because they consider only a few factors, making them unsuitable for complex and variable environments. Field tests rely on specific equipment, involve considerable time and economic costs, and do not allow for forward-looking predictive analysis. Although numerical analysis can economically simulate engineering problems, it still faces challenges in constructing complex field models. These limitations naturally motivate the use of data-driven artificial intelligence (AI) approaches, in which machine learning algorithms can capture nonlinear multivariate relationships and provide interpretable feature contributions. Given these advantages, AI modeling methods have enabled multi-parameter modeling with greater efficiency, becoming essential tools for solving complex engineering problems [

10,

11,

12,

13].

As feature dimensionality increases during the modeling process, redundant or irrelevant variables may trigger the curse of dimensionality. In this context, the importance of feature selection as an indispensable step in model construction cannot be ignored [

14]. Effective feature selection not only enhances model performance and interpretability but also significantly improves computational efficiency. The essence of feature selection methods lies in defining the mechanisms for subset search and subset evaluation. In general, according to their interaction with the learner, feature selection methods can be categorized into filter methods, wrapper methods, and embedded methods [

15]. Filter methods select features before model training by using statistical analysis to evaluate the importance of features, thereby retaining key features or eliminating those deemed unimportant. This approach offers the advantages of broad applicability and high computational efficiency, but it may not always identify the feature subset that maximizes model performance. In contrast, wrapper methods assess feature subsets based on algorithm performance, often selecting more optimal subsets than filter methods, but at the cost of higher computational costs. Embedded methods integrate feature selection within the model training process, offering lower computational costs compared to wrapper methods and better performance than filter methods. However, the outcomes of embedded methods depend on the specific model used, and different models may lead to different feature selection results. Based on search strategy, feature selection can be divided into exhaustive search, sequential search, and random search [

16]. In the context of random search, the metaheuristic algorithms, such as genetic algorithms [

17], particle swarm optimization [

18], ant colony optimization [

19], grey wolf optimizer [

20], and butterfly optimization [

21], have seen widespread use in recent years due to their excellent global optimization capabilities in feature selection [

14,

22,

23,

24,

25].

However, in the study of engineering problems, the application of metaheuristic methods for feature selection remains relatively limited. Researchers often instead use other methods to select feature subsets or directly use the full feature set for model training. For instance, Zhou et al. [

26] employed the Pearson chi-square test to assess the independence of features from the output variable, selecting five key features for random forest and Bayesian network models to predict ground vibrations. Hu [

27] applied the maximum information coefficient method to evaluate the contributions of various factors to the liquefaction potential, identifying 13 significant factors influencing gravelly soil liquefaction through a filtering method. Demir and Sahin [

28] explored the use of recursive feature elimination, Boruta, and stepwise regression to enhance the performance of tree-based algorithms, finding that the Boruta method performed best in predicting soil liquefaction. Nguyen et al. [

29] analyzed the correlations among features before developing a prediction model, but ultimately chose to use the complete feature set to predict peak vibration speeds in open-pit coal mines due to weak correlations. Hajihassani et al. [

30] directly utilized nine features to predict vibrations and air overpressure caused by blasting, without performing feature selection.

On the other hand, metaheuristic algorithms have been widely adopted to optimize model hyperparameters. For instance, Azimi et al. [

31] utilized genetic algorithms to optimize the architecture of an artificial neural network, improving the prediction accuracy of blasting vibration in open-pit copper mines. He et al. [

32] employed the grey wolf optimizer (GWO), whale optimization algorithm (WOA), and tunicate swarm algorithm (TSA) to search for the optimal hyperparameters of a random forest (RF) model, and found that the RF-TSA model provided a robust solution for predicting overbreak caused by tunnel blasting. Tang and Na [

33] used particle swarm optimization and grid search to optimize the hyperparameters of four different machine learning models for predicting ground settlement in various tunnels. Qiu et al. [

34] fine-tuned hyperparameters of the XGBoost model using GWO, WOA, and Bayesian optimization, and compared the resulting models with an unoptimized baseline, demonstrating that hyperparameter optimization can significantly enhance predictive performance. Furthermore, metaheuristic algorithms such as particle swarm optimization, ant colony algorithm, and artificial bee colony have also been utilized to enhance the performance of models, providing effective support for solving engineering problems [

35,

36,

37,

38].

Although numerous methods have been proposed for feature selection and hyperparameter optimization, these two processes are often conducted independently, which can lead to suboptimal performance of the final model. When seeking the best model, the optimal feature subset and the best model hyperparameters should be solved simultaneously. For a specific feature subset, there exists a corresponding set of optimal hyperparameters; similarly, for a given set of hyperparameters, there is a corresponding optimal feature subset.

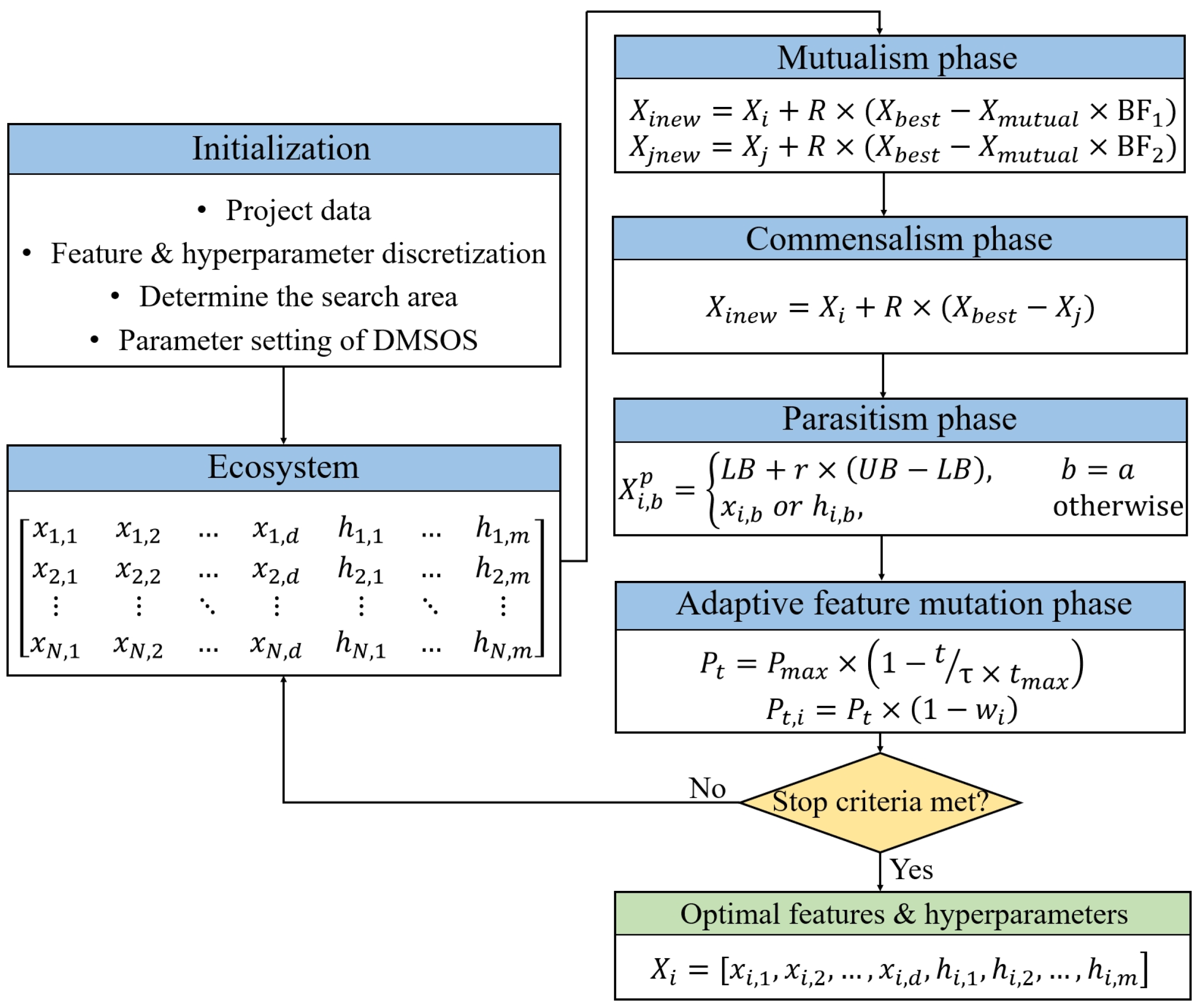

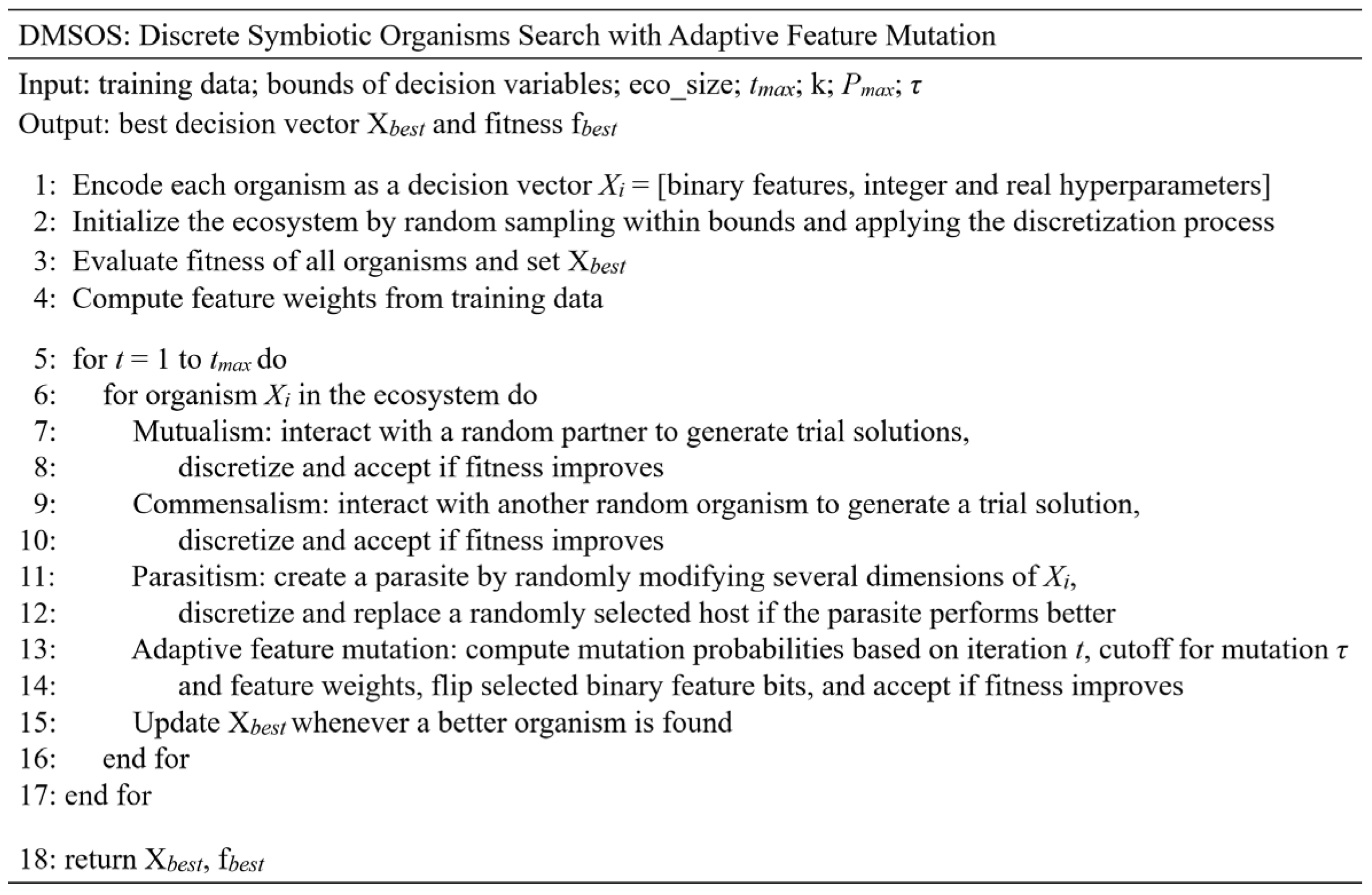

Therefore, this study proposes a systematic framework that integrates feature selection and hyperparameter optimization. First, a preliminary feature selection method is developed to eliminate redundant variables based on prior knowledge and statistical analysis. Second, a novel discrete symbiotic organisms search algorithm with adaptive feature mutation (DMSOS) is introduced. This algorithm simultaneously optimizes features and hyperparameters for the XGBoost model, enhanced by a mutation strategy based on time and weight to balance exploration and exploitation during optimization. Finally, the proposed DMSOS-XGBoost model is validated based on the blasting vibration data of a shaft project and compared with other sequential modeling strategies, and the feature importance analysis of the model provides guidance for field construction.

4. Feature Importance Analysis

Based on the preceding analysis, distinct performance differences have emerged among the models. To explain the differences, it is crucial to investigate how each model utilizes input features to make predictions. Although tree-based global explanation provides the overall impact of features, it lacks the contribution of particular features to individual predictions. To address this limitation, this study employs the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) method to interpret each predictive model. SHAP is an innovative explanation method that directly measures local feature interaction effects and offers a comprehensive understanding of the global model structure by aggregating local explanations of each prediction [

49].

Figure 15 presents the global SHAP-based feature importance for all models. In the first three predictive models (AFDH-XGBoost, PFDH-XGBoost and PFOH-XGBoost), seven features make significant contributions, with the D, Q, and H consistently ranked among the most influential variables. This pattern is consistent with classical vibration attenuation theory, in which the geometric spreading of waves and the input explosive energy jointly control the PPV level. In contrast, in the DHOF-XGBoost and DMSOS-XGBoost models, the number of strongly contributing features is reduced to five, indicating that redundant or weakly informative variables have been largely eliminated and that the prediction relies on a smaller set of physically meaningful features. The global importance patterns of AFDH-XGBoost and PFDH-XGBoost are also very similar, explaining their comparable predictive performance and suggesting that the preliminary feature selection step does not change the dominant physical controls on vibration. Across all models, feature Q is always identified as highly important, which is physically reasonable because the explosive charge directly determines the input energy of the blast and thus the overall vibration amplitude. In contrast, the DMSOS-XGBoost model not only captures the energy input and geometric attenuation, but also particularly highlights the critical contribution of feature A to the prediction outcomes, which indicates that the model successfully captures the elevation amplification effect in blasting vibration propagation. By assigning higher importance to A, DMSOS-XGBoost captures these site-specific propagation and amplification effects more clearly than the other models.

As shown in

Figure 16a, a local analysis was performed on the 24th sample point in

Figure 14 to explore the causes of significant prediction errors in a single forecast. These errors represent localized residuals from a minority of samples, and their impact on the overall fitting quality is not significant. As shown in

Figure 16b–f, the contributions of features in the local explanation waterfall plots for the AFDH-XGBoost and PFDH-XGBoost models were consistent, leading to the same prediction value. In this particular prediction sample, spatial geometry features D, H, and R, along with the explosive charge feature Q, made significant positive contributions, resulting in a prediction value higher than the actual value. Similarly, in the DHOF-XGBoost model, contributions from all features were also positive, which resulted in significant prediction errors. In the PFOH-XGBoost and DMSOS-XGBoost models, features Q and CPH from the explosive charge feature group had negative contributions to the prediction results, which offset part of the positive contributions from the spatial geometry feature group, thus bringing the prediction closer to the actual value.

In summary, spatial geometric relationships and the explosive charge are key factors in vibration control. In engineering construction, to ensure the safety of structures near blasting sources, safe distances must be strictly maintained. For immovable structures, appropriate adjustment of the explosive charge can be employed to minimize potential impacts on these structures and the surrounding environment. Additionally, particular attention should be paid to protecting structures in high-altitude areas, as these regions may experience more intense vibration effects, thereby increasing safety risks during construction.

5. Discussion

Although the proposed hybrid framework has been successfully validated and practically applied in an engineering project, several limitations remain. These limitations also highlight potential directions for future research.

Despite achieving the best overall performance, DMSOS requires a higher computational budget due to repeated fitness evaluations throughout the search process. Each evaluation requires training an XGBoost model under cross-validation, which dominates the overall runtime. By comparison, the additional operations introduced by DMSOS, such as the discretization process and the adaptive mutation mechanism, are lightweight relative to model training. Therefore, the total runtime is mainly governed by the ecosystem size, the maximum number of iterations, and the number of cross-validation folds. From an engineering standpoint, this extra cost is acceptable because improved predictive accuracy helps reduce the risk of blasting vibration, which could otherwise lead to structural damage or subsequent disputes. In practice, the computational burden can be alleviated through several strategies, such as reducing the number of cross-validation folds, employing early stopping rules when rapid decisions are needed, or leveraging parallel computing. These approaches offer flexible trade-offs between computational efficiency and solution quality.

The sensitivity of parameter settings requires further investigation. Both the preliminary feature selection and the DMSOS algorithm involve several parameter settings, such as the correlation threshold for the filtering process, the adaptive mutation probability strategy, and the bounds of the hyperparameter search space. In this study, these settings were mainly determined through preliminary trials or empirical selection, without a comprehensive parameter sensitivity analysis. Therefore, the impact of different parameter configurations on the feature and hyperparameter optimization results has not been quantified. Future research will involve a comprehensive sensitivity analysis and explore adaptive control strategies for DMSOS, thereby reducing the dependence on manual parameter tuning.

Comparative analysis with other algorithms and evaluation on multiple datasets would better demonstrate the overall performance of the proposed method. The primary objective of this study was to improve the original SOS algorithm, enabling it to simultaneously optimize features and model hyperparameters, thereby providing more reliable guidance for field construction, and offering a reference for improving other algorithms facing simultaneous optimization challenges. However, while DMSOS shows improvements over the original SOS and other sequential modeling approaches, its performance relative to other optimization algorithms remains to be fully verified. Furthermore, validation relied on measurement data from a single engineering project with limited feature diversity. Future work should include systematic testing on datasets with varying dimensionalities and noise characteristics, along with statistical comparisons between DMSOS and other optimization algorithms.

Further validation is needed regarding the generalizability of the engineering applications. Although validated with blasting vibration data, whether the identified optimal parameters and selected features can be generalized to other mining regions remains to be verified. Subsequent work will extend the application to multiple mining areas, varying operational conditions, and other geotechnical engineering problems to evaluate its broader applicability.

In summary, this study reduced data dimensionality through preliminary feature selection and simultaneously addressed the interdependency between features and hyperparameters in complex engineering modeling. These efforts effectively enhanced the performance of the predictive model. Future research focusing on parameter sensitivity, computational efficiency, and generalizability across different scenarios will further enhance the reliability and applicability of the proposed hybrid framework in diverse engineering contexts.