Study on Degradation of Oxytetracycline in Water by PMS Activated by Modified Macadamia Nut Shell Biochar

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Reagents and Instruments

2.2. Preparation of Catalyst

2.3. Experimental Methods

2.4. Analysis Method

3. Results and Discussion

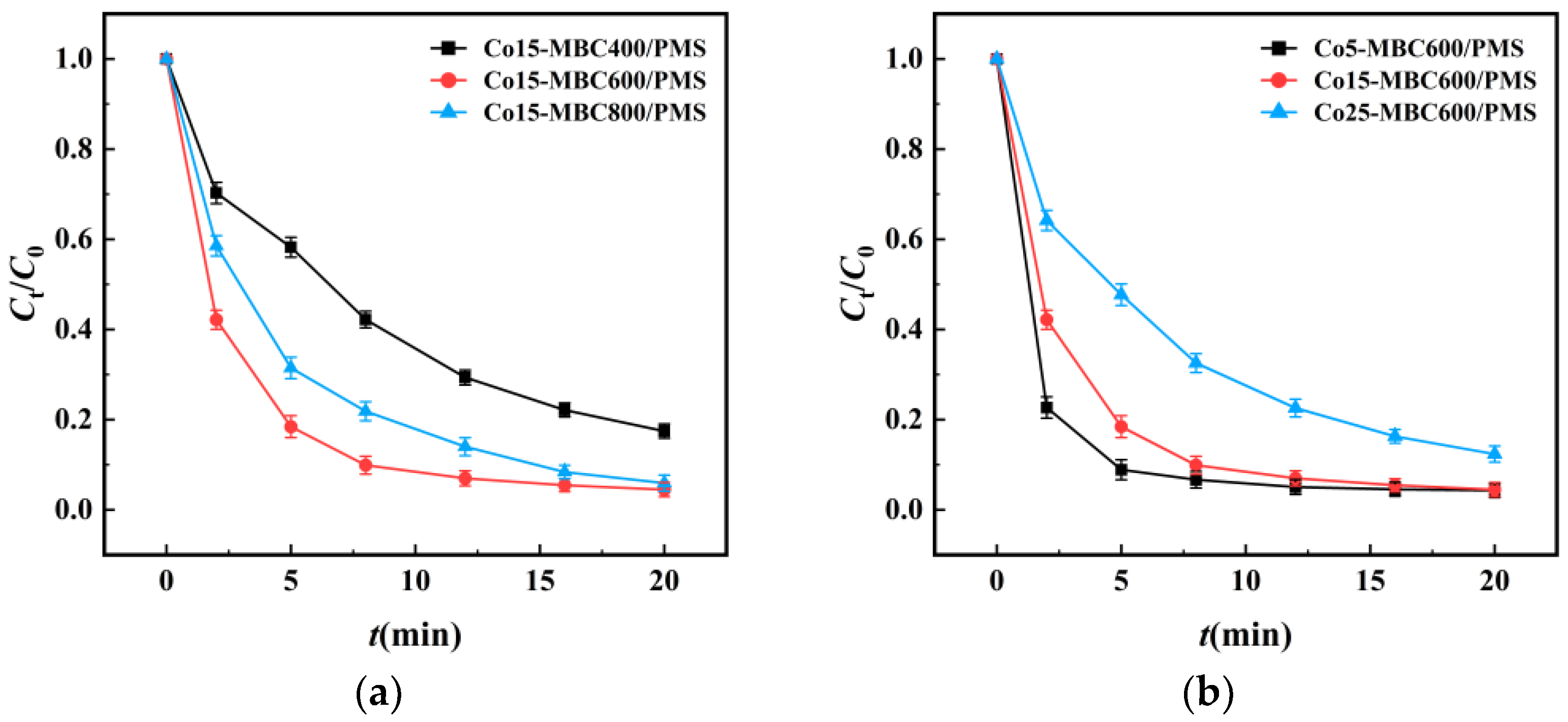

3.1. Preparation Conditions

3.2. Physical Properties and Characteristics of Biochar

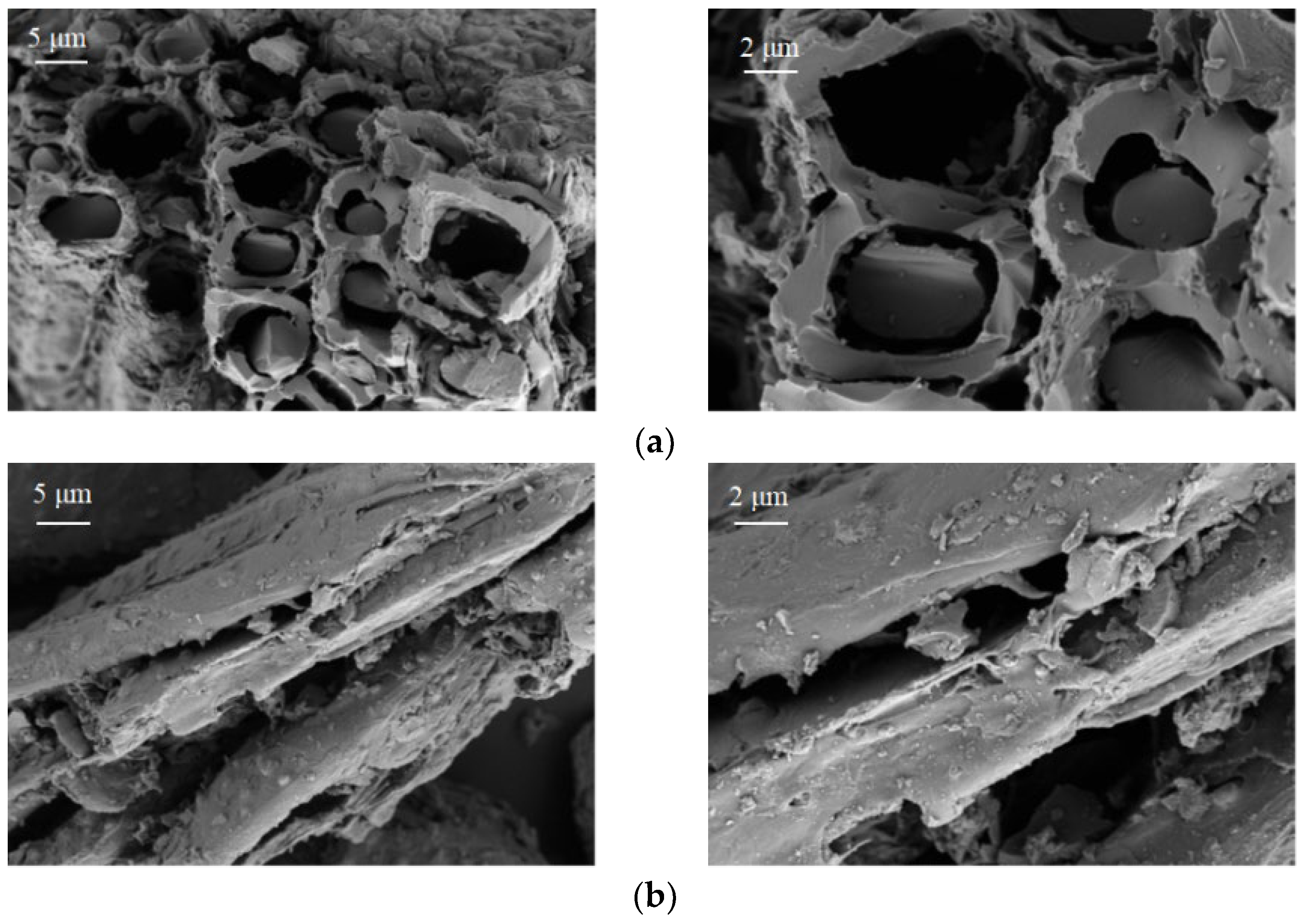

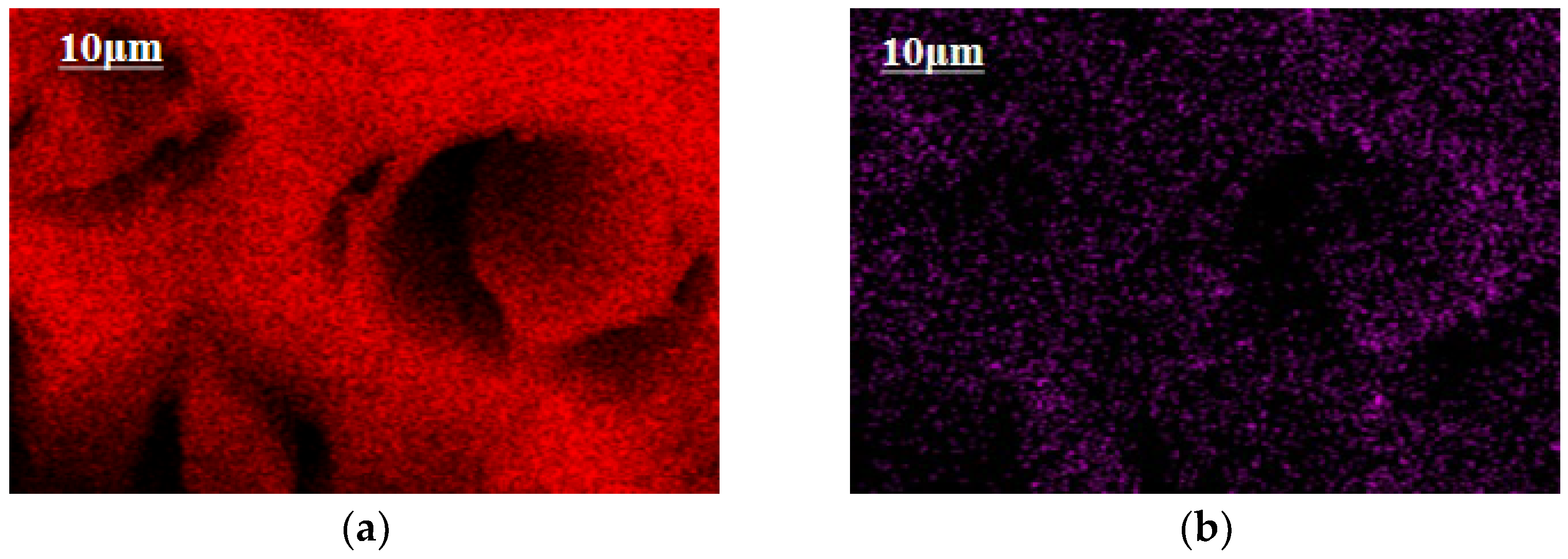

3.2.1. SEM-EDS Analysis

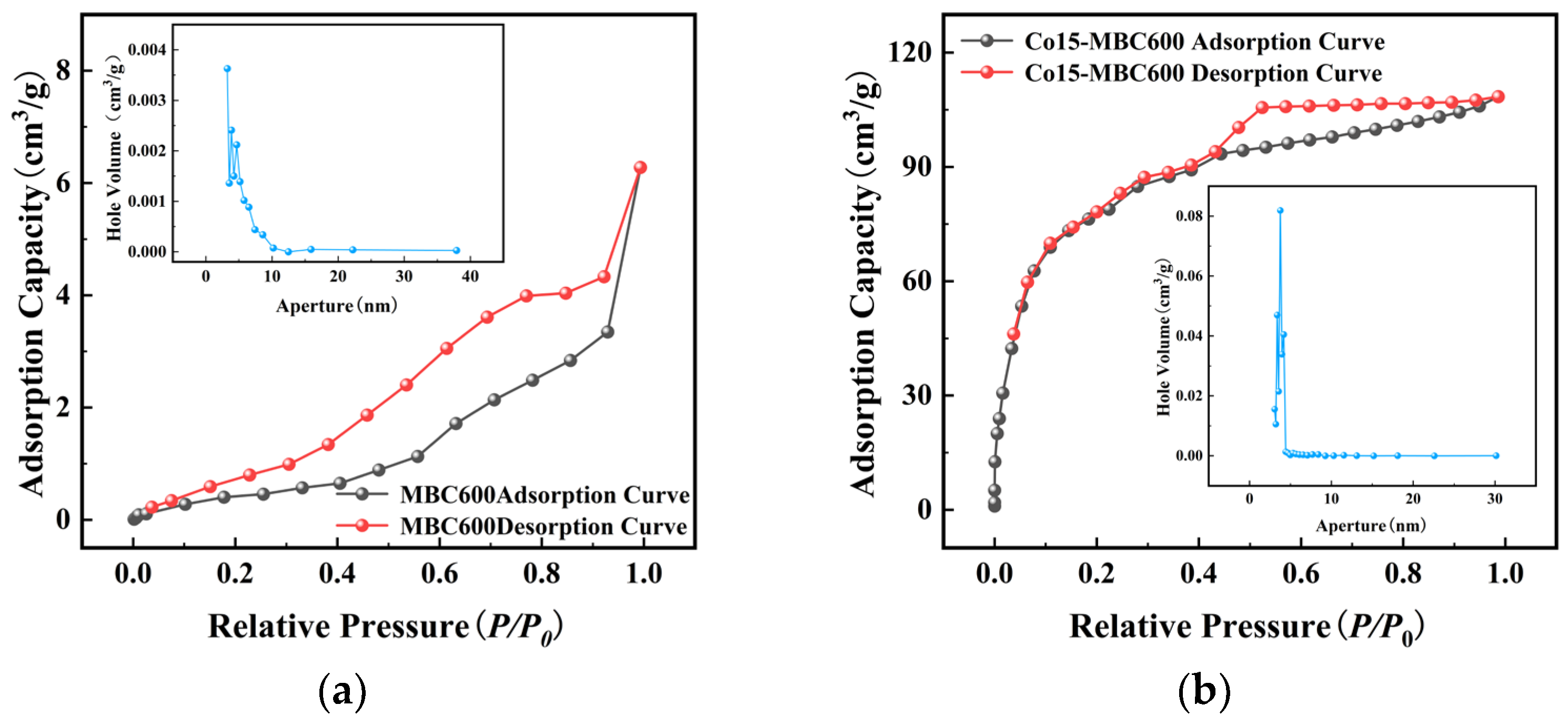

3.2.2. BET Analysis

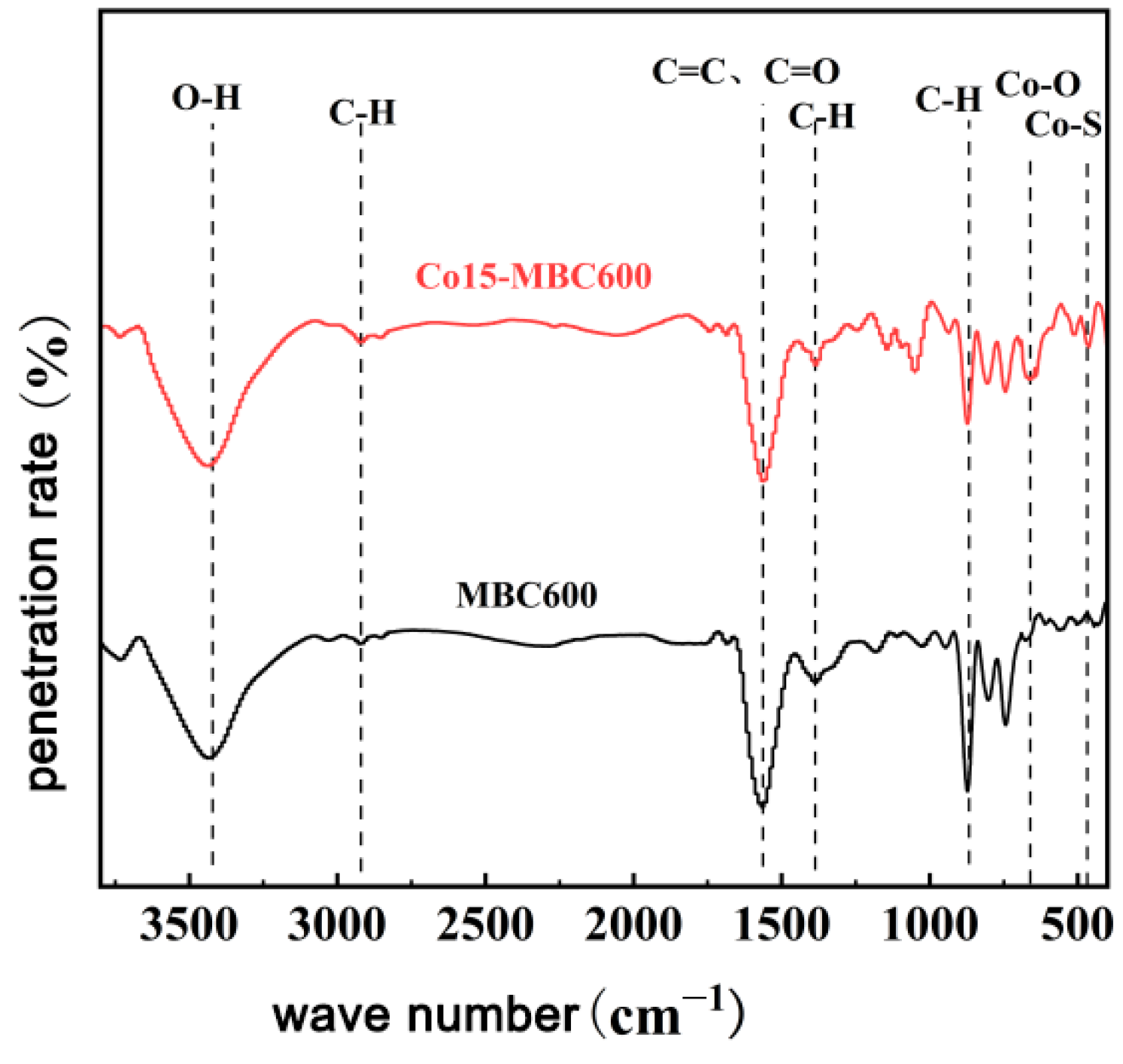

3.2.3. FT-IR Analysis

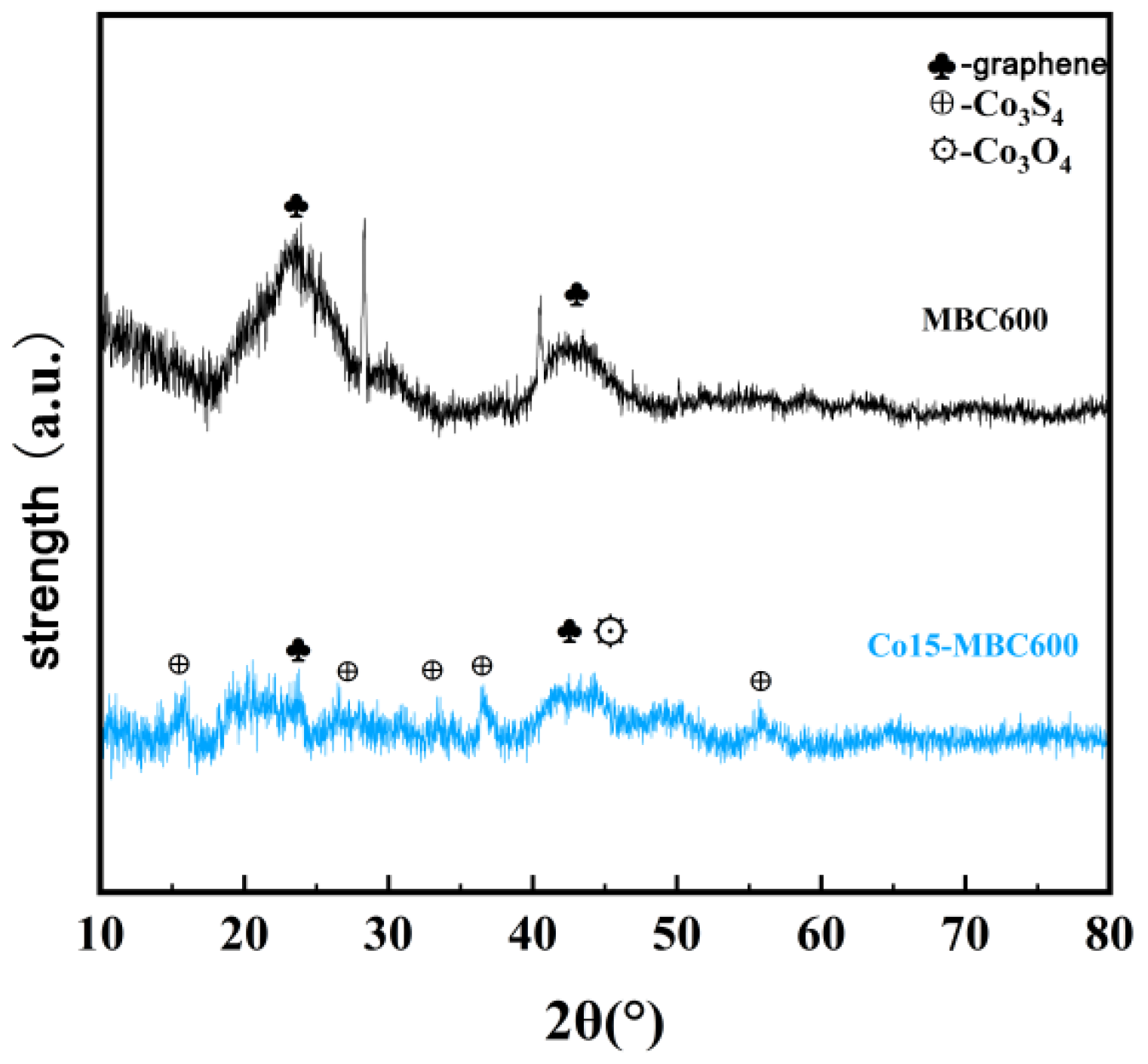

3.2.4. XRD Analysis

3.3. Study on the Influencing Factors of OTC Degradation by PMS Activated by Co15-MBC600

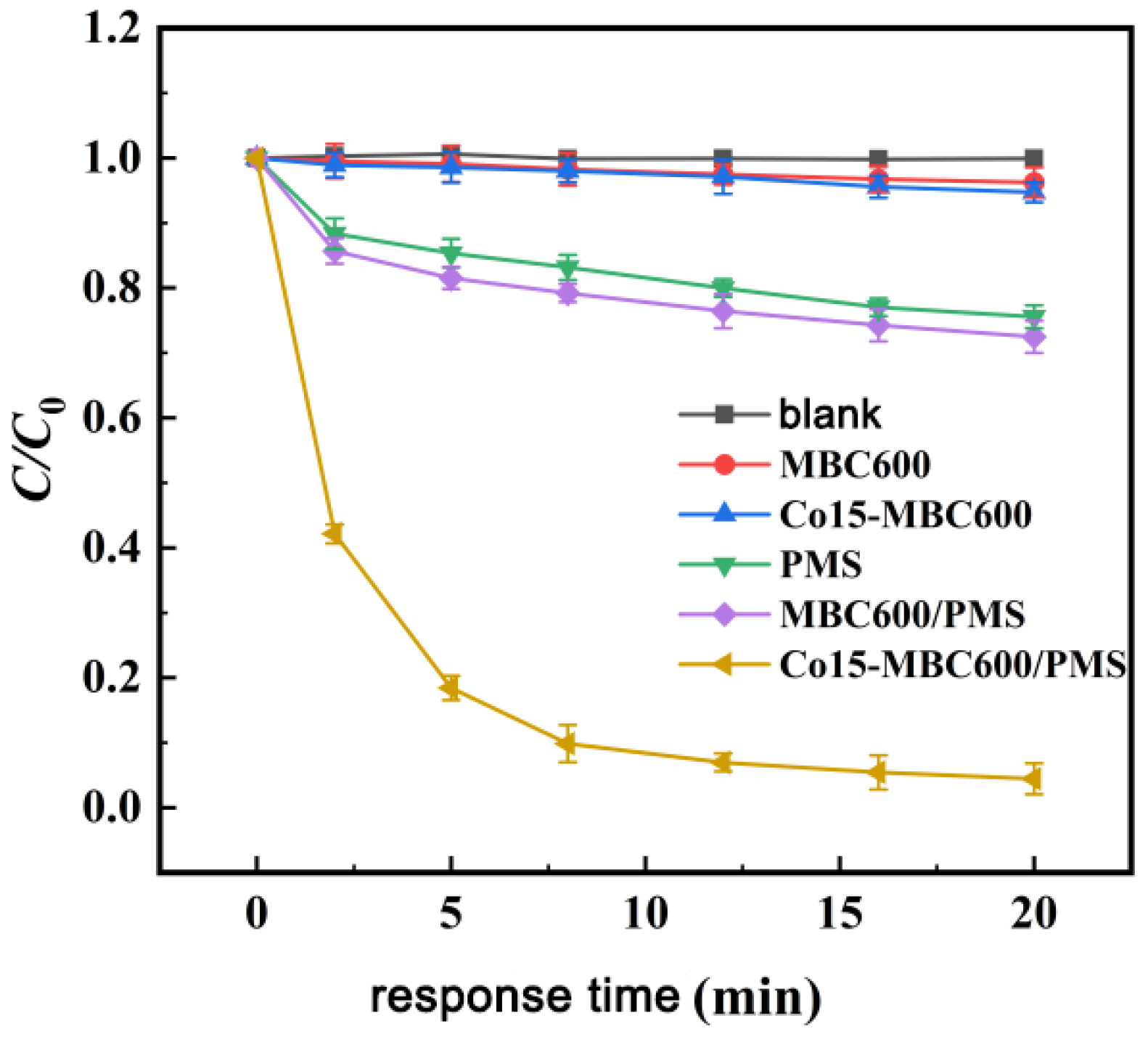

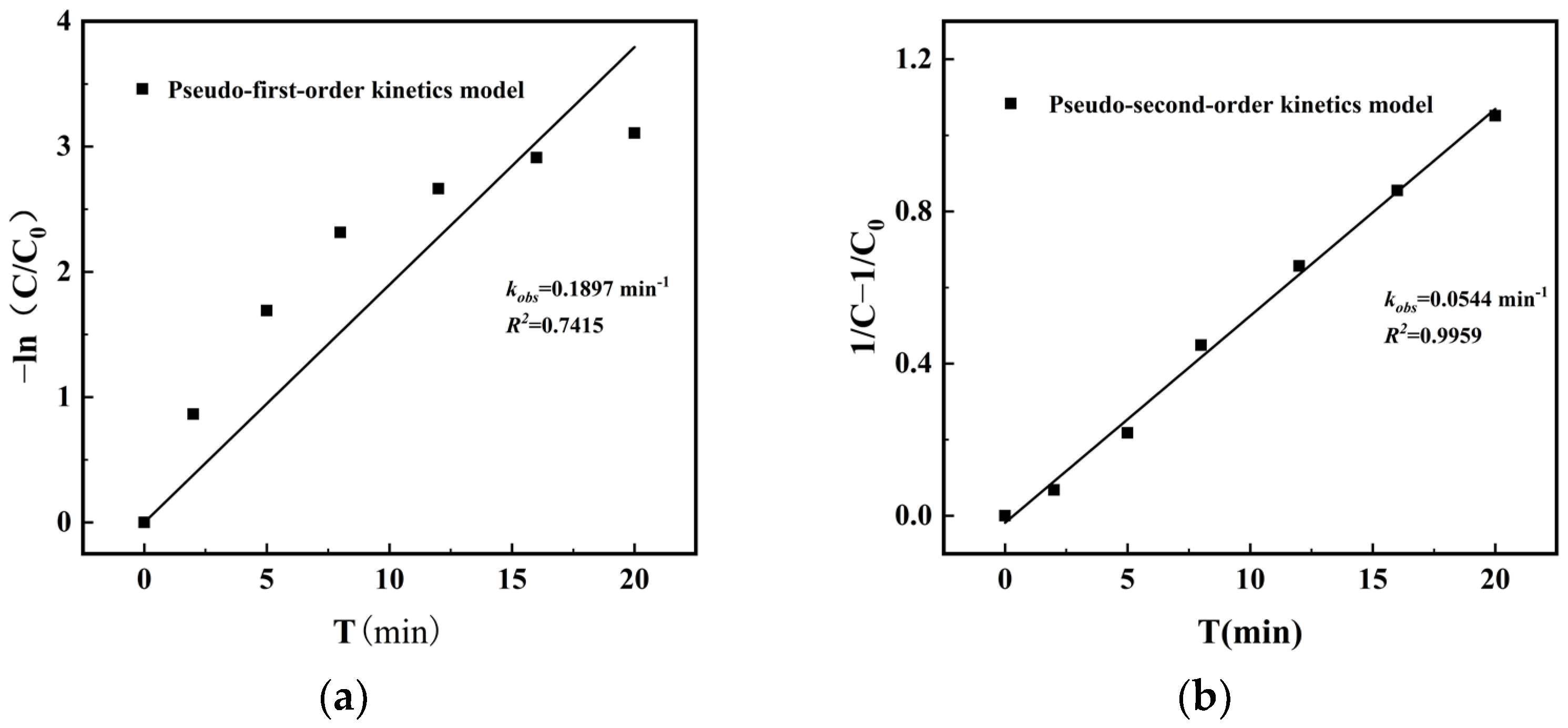

3.3.1. Effect Comparison of OTC Degradation in Different Systems

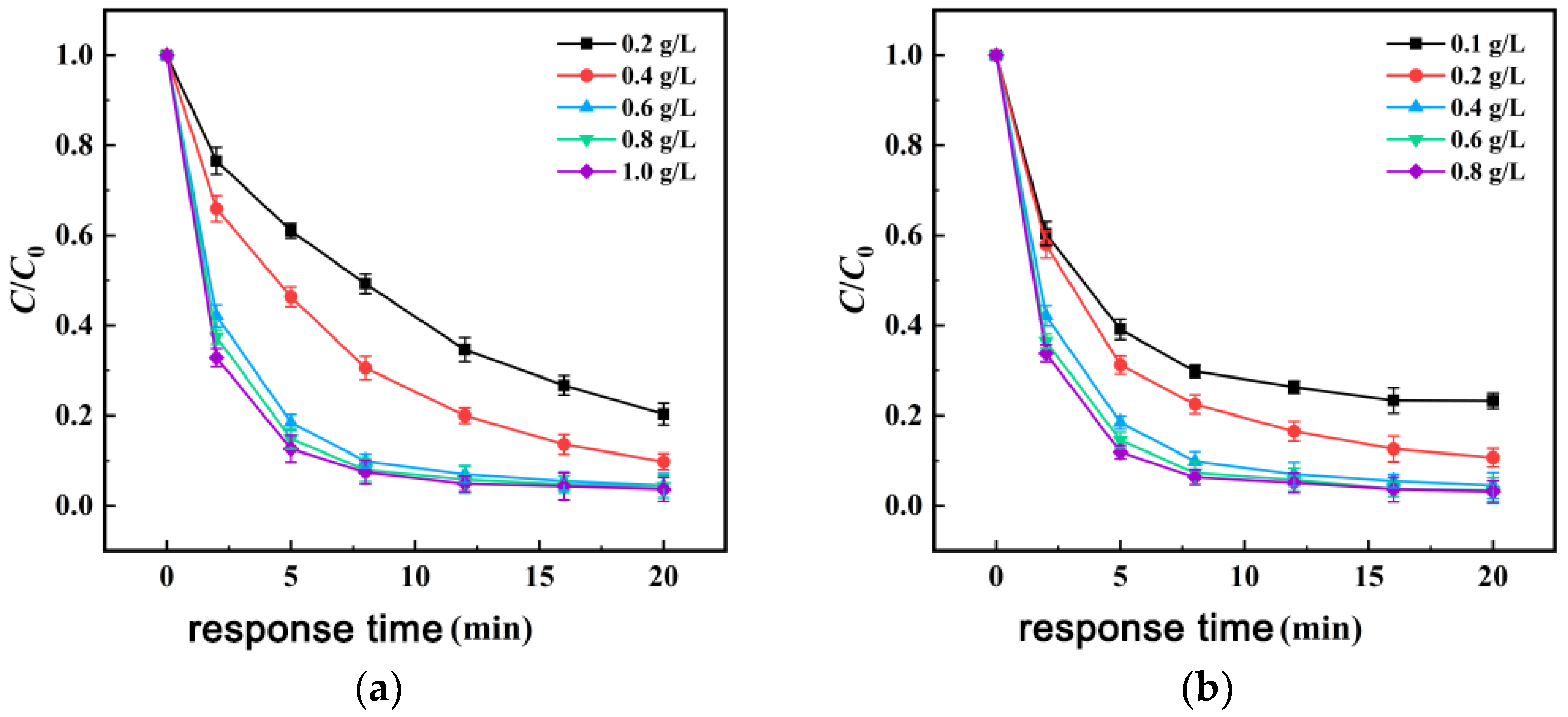

3.3.2. Influence of Co15-MBC600 and PMS Dosages

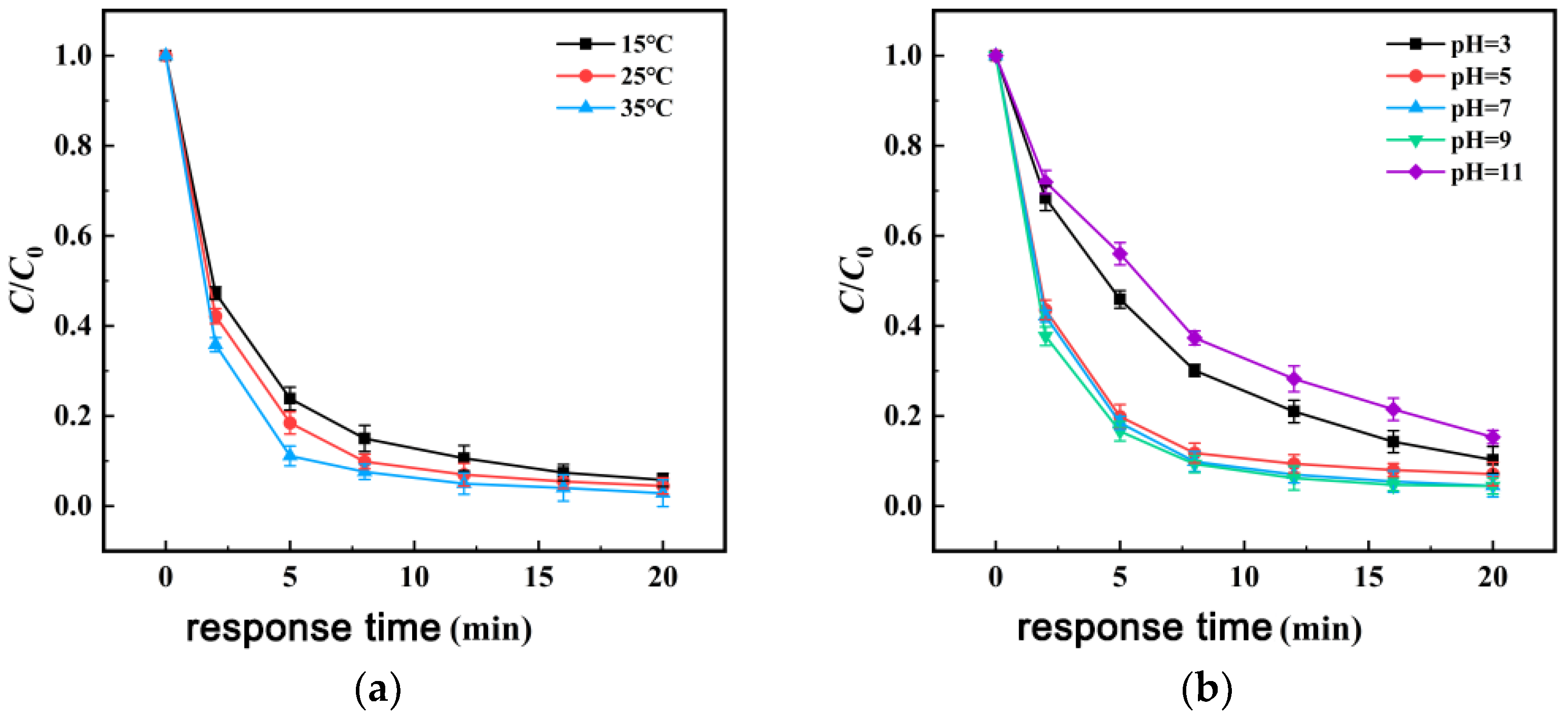

3.3.3. Influence of Temperature

3.3.4. Influence of Solution pH

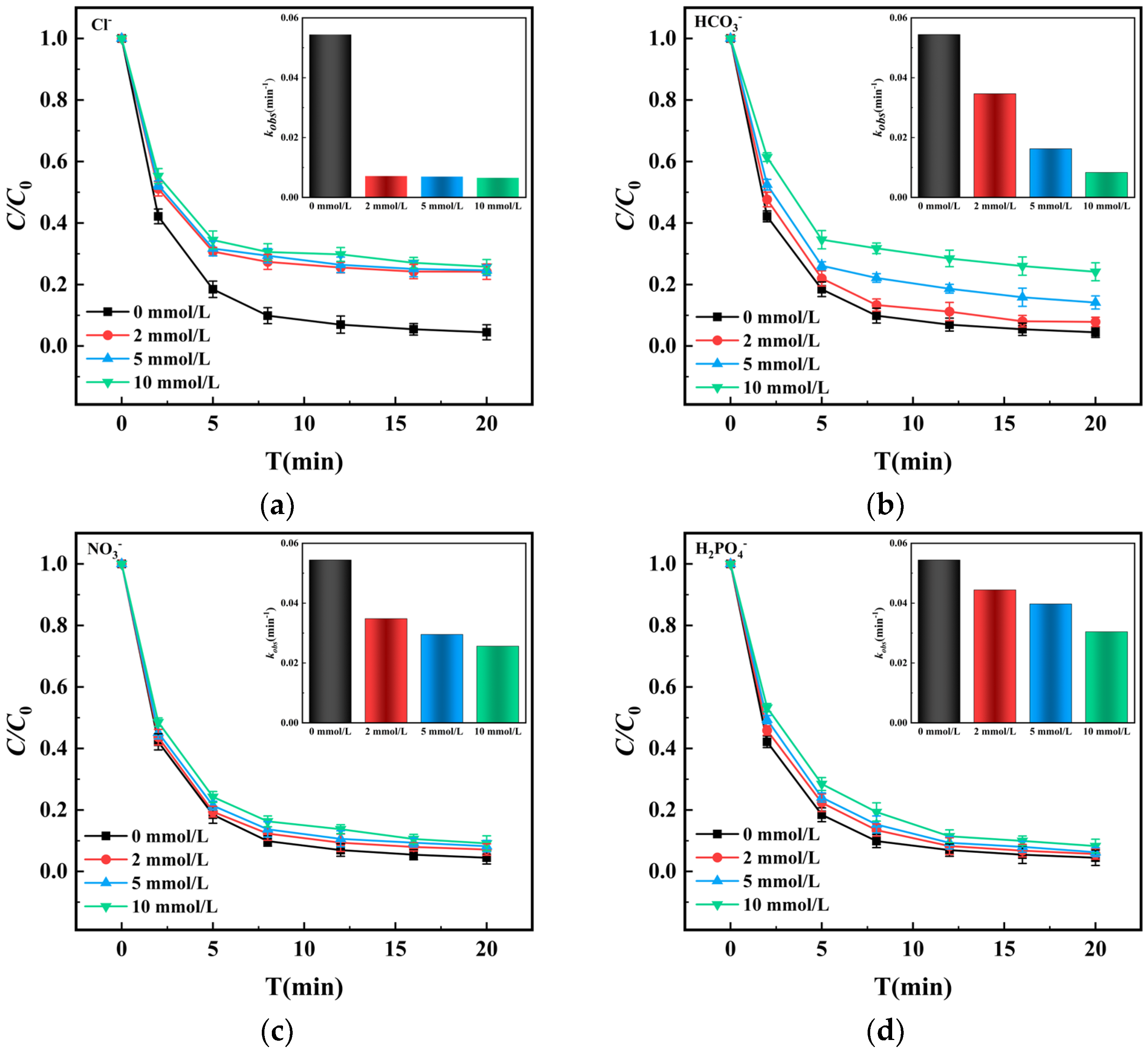

3.3.5. Influence of Inorganic Anions

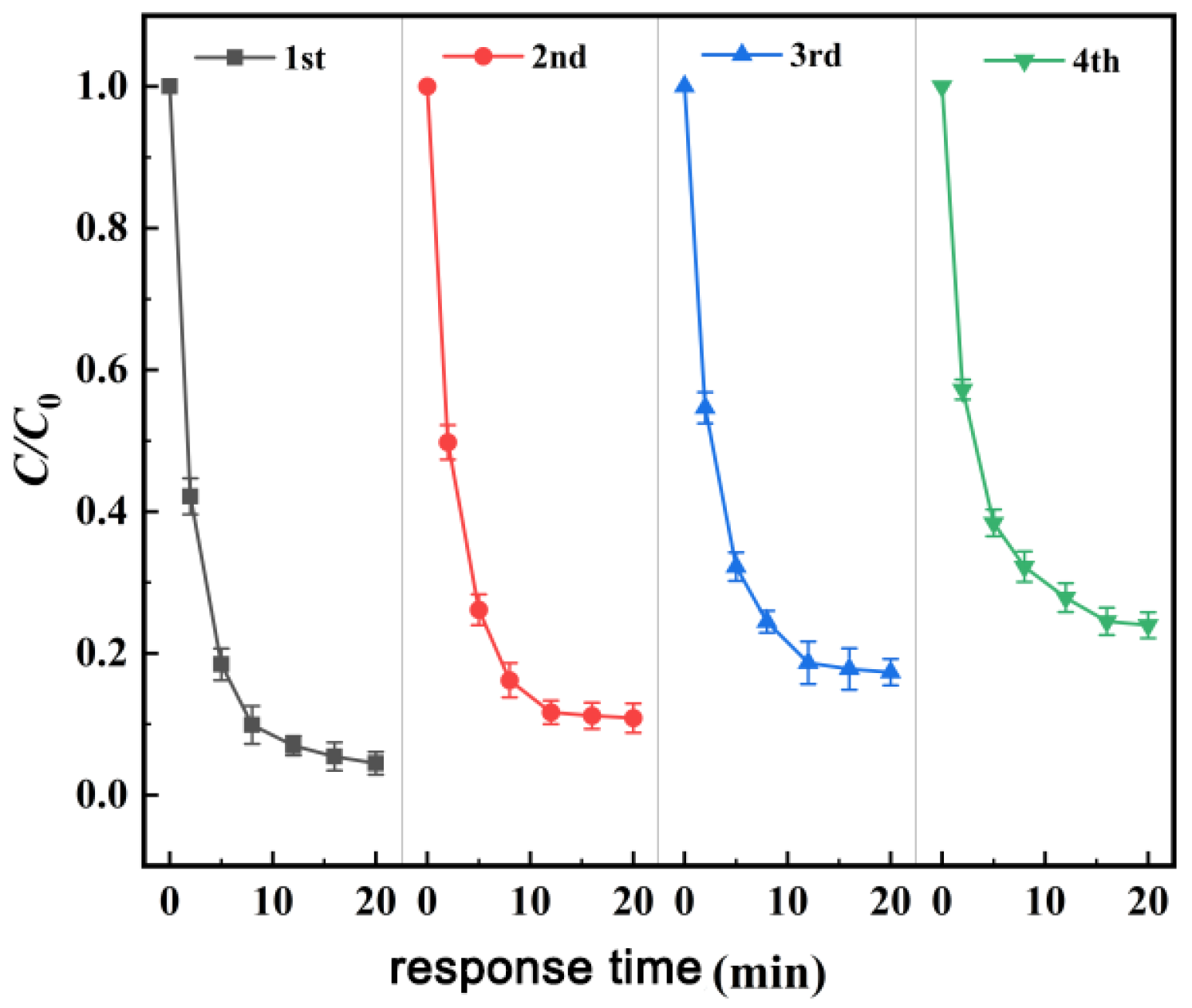

3.4. Study on the Stability of Materials

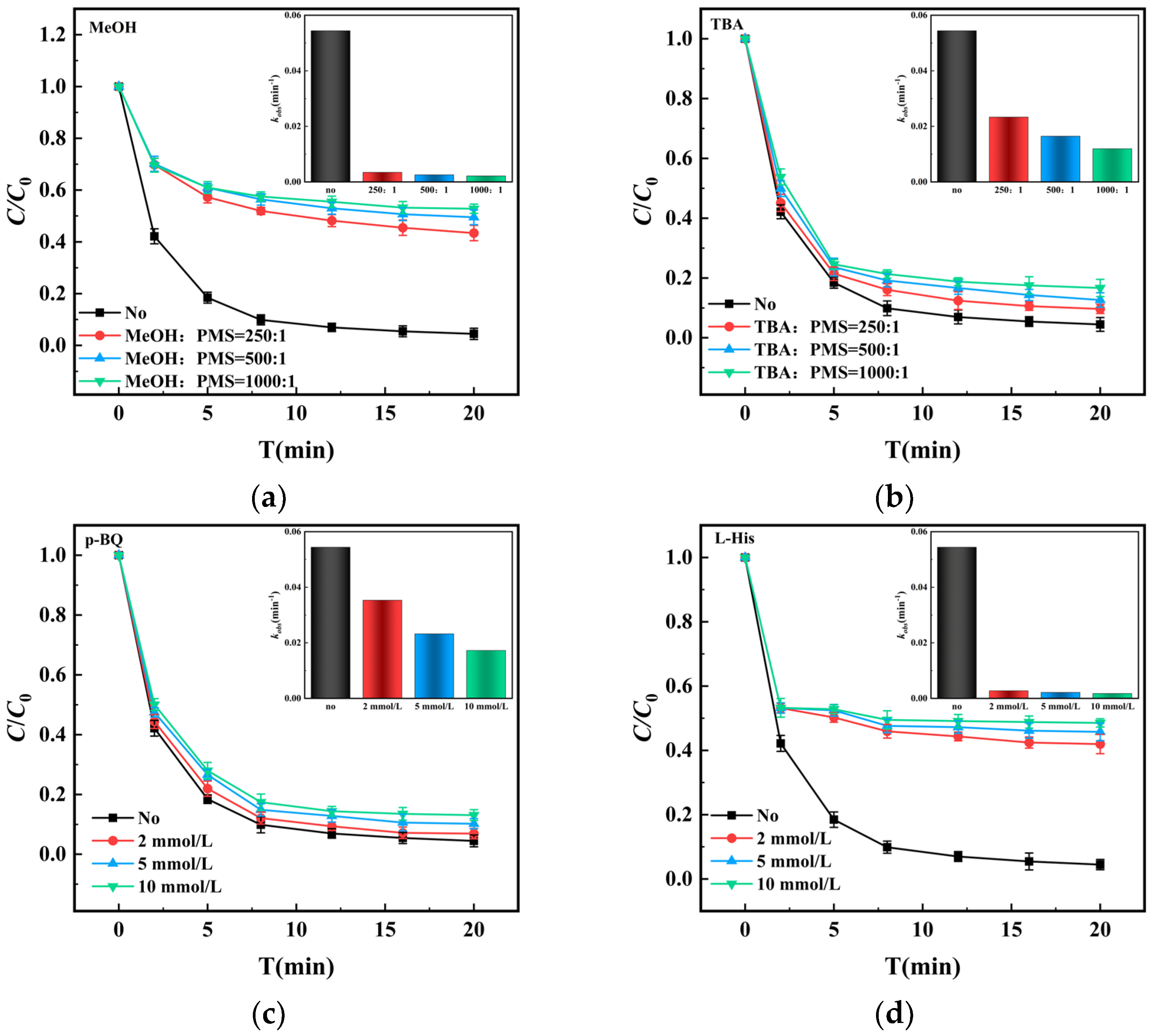

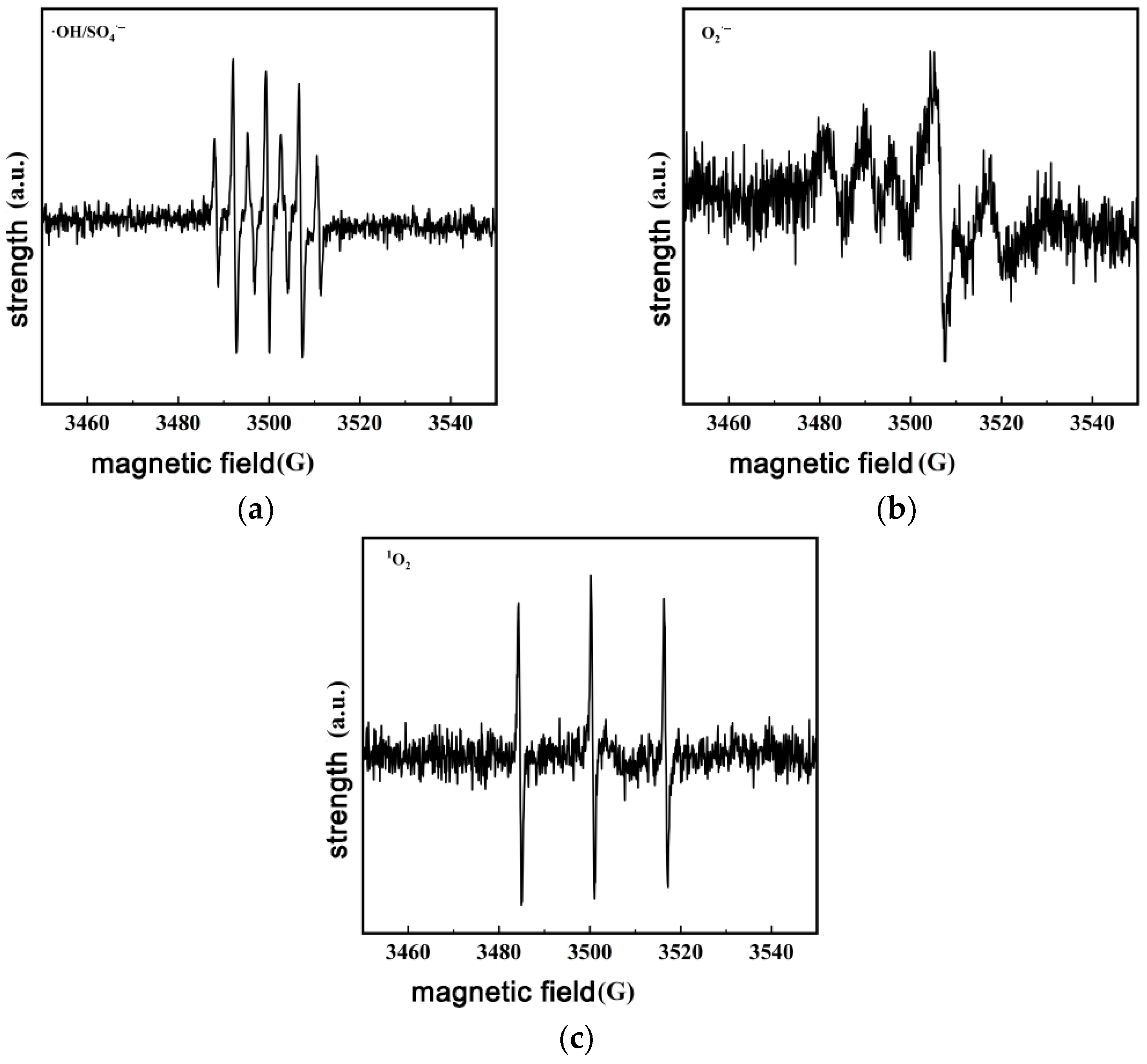

3.5. Detection of Reactive Species

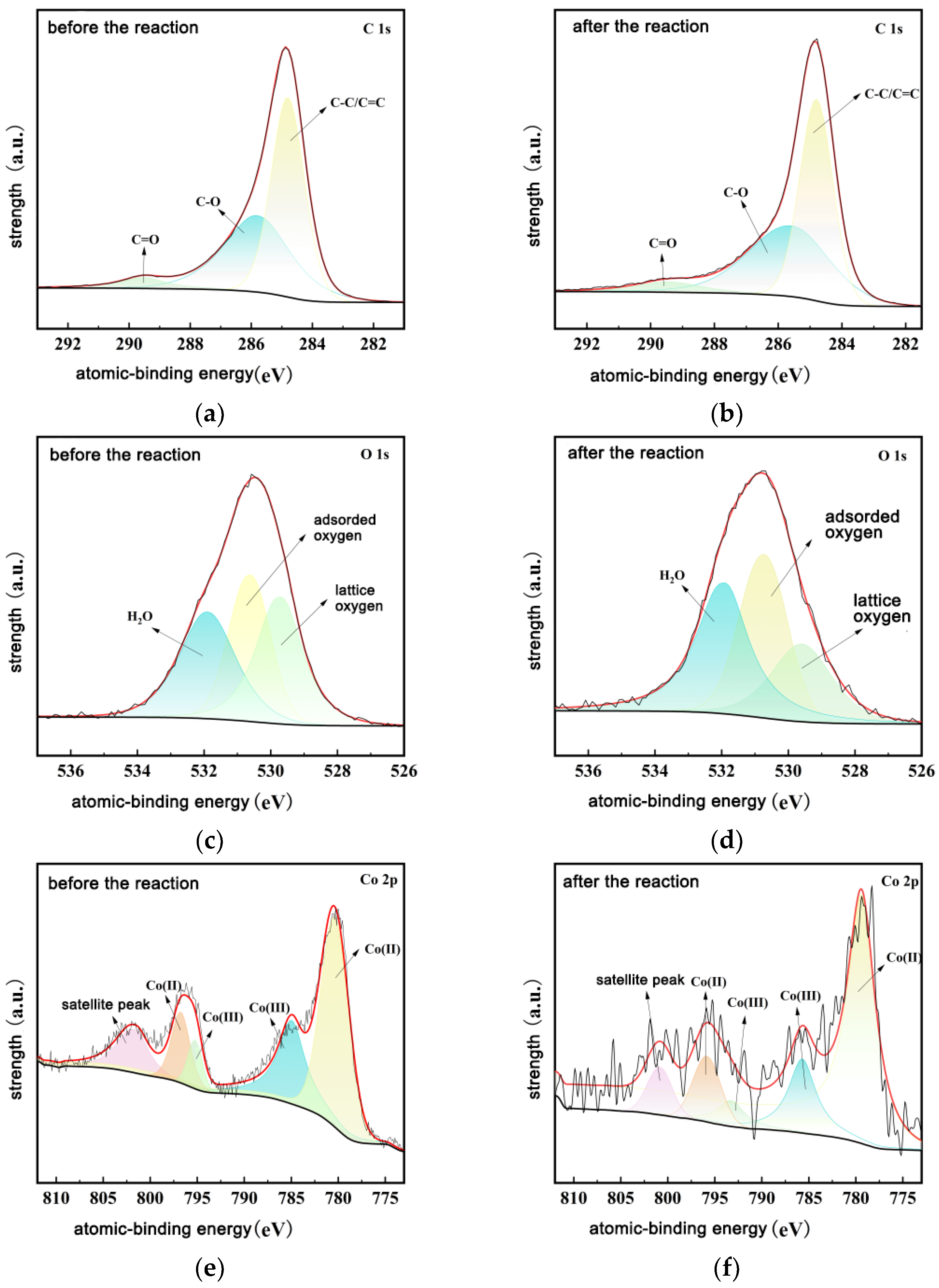

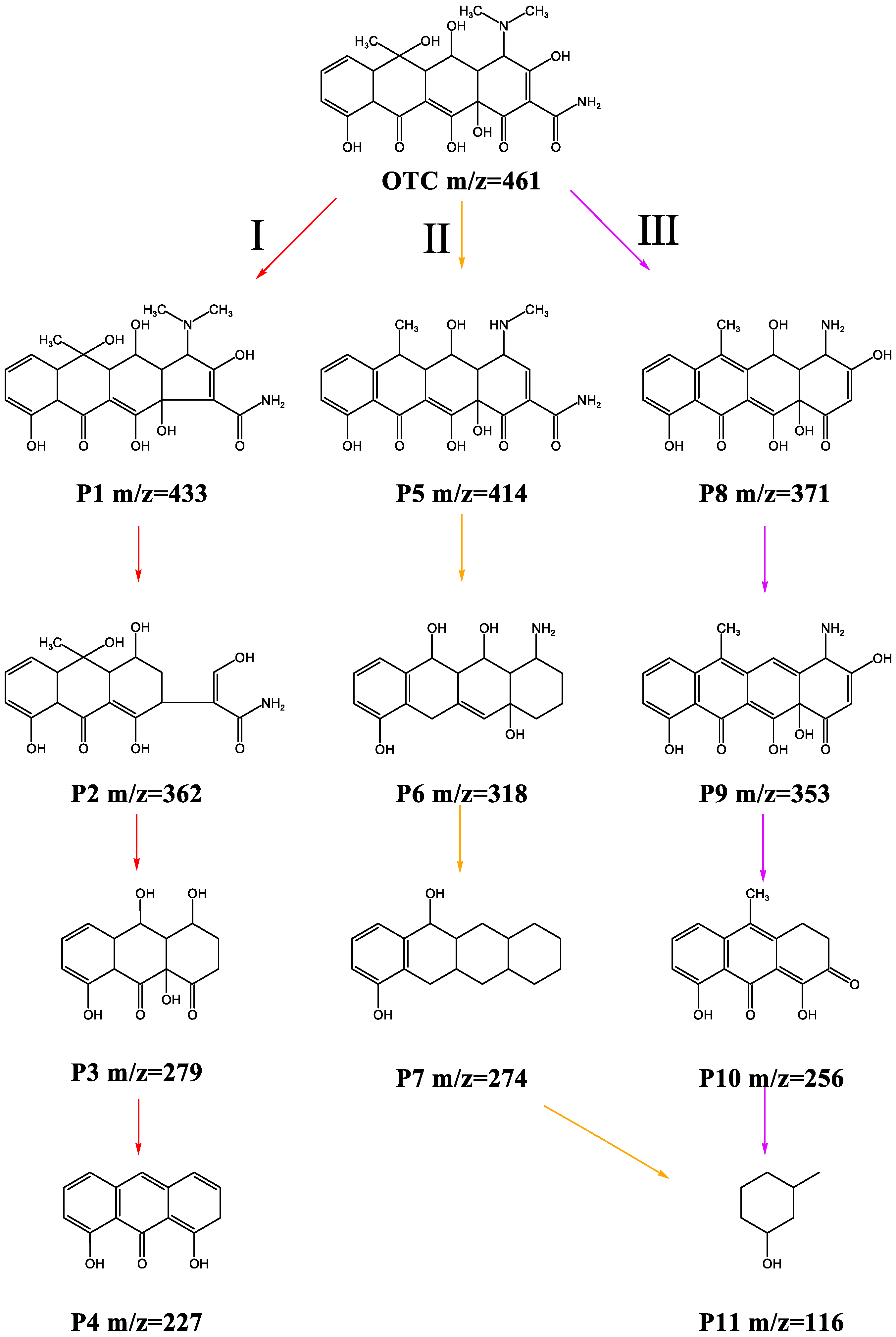

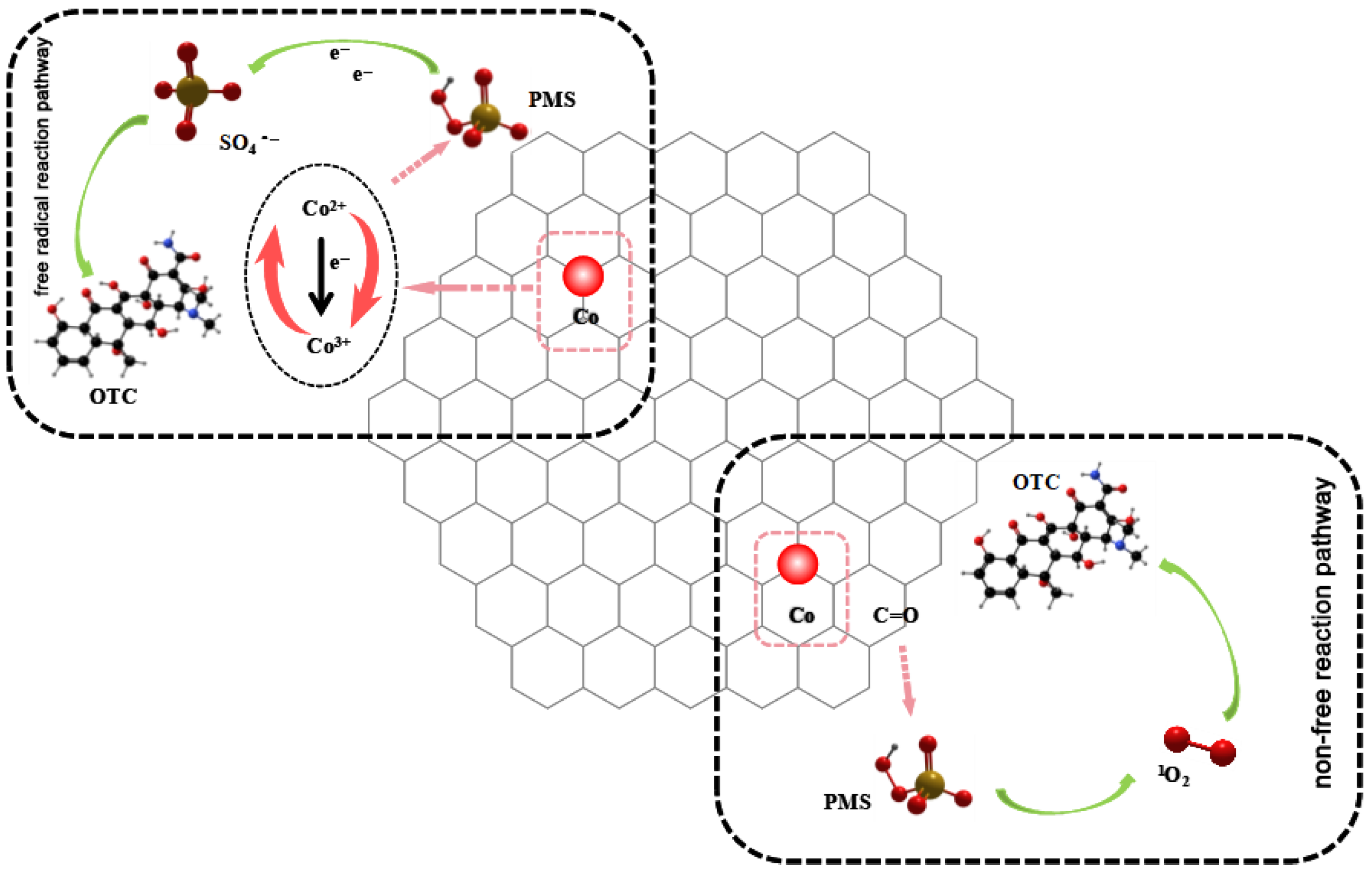

3.6. Study on OTC Degradation Mechanism

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, D.; Yang, M.; Hu, J.; Ren, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, K. Determination and Fate of Oxytetracycline and Related Compounds in Oxytetracycline Production Wastewater and the Receiving river. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2008, 27, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, D. Various Antibiotic Contamination in Natural Sources: Effects on Environment Including Animals and Humans (A-Review). Orient. J. Chem. 2024, 40, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.; Ebrahim, S.; Jian, L. Degradation mechanisms of oxytetracycline in the environment. J. Integr. Agric. 2019, 18, 1953–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Hu, Y.; Cheng, J.; Chen, Y. Degradation of Oxytetracycline (OTC) and Nitrogen Conversion Characteristics Using A Novel Strain. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 354, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Wang, C.; Mao, D.; Luo, Y. The Occurrence and Fate of Tetracyclines in Two Pharmaceutical Wastewater Treatment Plants of Northern China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 1722–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, D.; Yi, H.; Lai, C.; Liu, X.; Huo, X.; An, Z.; Li, L.; Fu, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, M.; et al. Critical Review of Advanced Oxidation Processes in Organic Wastewater Treatment. Chemosphere 2021, 275, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Liu, D.; Huang, W.; Wei, X.; Huang, W. Biochar Supported CuO Composites Used as An Efficient Peroxymonosulfate Activator for Highly Saline Organic Wastewater Treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 721, 137–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Long, M. Cobalt-Catalyzed Sulfate Radical-Based Advanced Oxidation: A Review on Heterogeneous Catalysts and Applications. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2016, 181, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milh, H.; Cabooter, D.; Dewil, R. Role of Process Parameters in the Degradation of Sulfamethoxazole by Heat-Activated Peroxymonosulfate Oxidation: Radical Identification and Elucidation of the Degradation Mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 422, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, G.; Gao, J.; Liu, C.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, D. Key Role of Persistent Free Radicals in Hydrogen Peroxide Activation by Biochar: Implications to Organic Contaminant Degradation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 1902–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, G.; Liu, C.; Gao, J.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Zhou, D. Manipulation of Persistent Free Radicals in Biochar to Activate Persulfate for Contaminant Degradation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 5645–5653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, M.; Zhang, B.; Yang, F.; Li, X.; Shi, W.; Yan, S.; Tang, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, X. Analysis of Fatty Acid Composition and Concentration in the Kernel of Seven Main Macadamia Cultivars from Yunnan. J. Fruit Sci. 2025, 41, 828–839. [Google Scholar]

- Shabalala, M.; Toucher, M.; Clulow, A. The Macadamia bloom—What are the hydrological implications. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 292, 110628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Z.; Guo, G.; He, F.; Zeng, H.; Tu, X.; Wang, W. An Analysis of the Main Nutrient Components of the Fruits of Different Macadamia (Macadamia integrifolia) Cultivars in Rocky Desertification Areas and a Comprehensive Evaluation of the Mineral Element Contents. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.G.; Ko, S.O. Effects of Thermal Modification of A Biochar on Persulfate Activation and Mechanisms of Catalytic Degradation of A Pharmaceutical. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 399, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, G. Iron-Copper Bimetallic Nanoparticles Embedded Within Ordered Mesoporous Carbon as Effective and Stable Heterogeneous Fenton Catalyst for the Degradation of Organic Contaminants. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2015, 164, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, Q.-Q.; Wang, F.J.; Zhao, Y.-T.; Zhou, Q. Application of Iron and Sulfate-Modified Biochar in Phosphorus Removal from Water. Environ. Sci. 2021, 42, 2313–2323. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.; Zhang, X.P.; Zhang, J.Q.; Tang, Y.X.; Luo, Z. Preparation of ZVI-biochar derived from magnetically modified sheep manure and its activation of peroxymonosulfate to degrade AO7. Acta Sci. Circumstantiae 2022, 42, 196–208. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.; Guo, W.; Wang, H.; Du, J.; Wu, Q.; Chang, J.-S.; Ren, N. Singlet Oxygen-Dominated Peroxydisulfate Activation by Sludge-Derived Biochar for Sulfamethoxazole Degradation Through A Nonradical Oxidation Pathway: Performance and Mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 357, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Bo, S.; Qin, Y.; An, Q.; Xiao, Z.; Zhai, S. Transforming Goat Manure Into Surface-Loaded Cobalt/Biochar as PMS Activator for Highly Efficient Ciprofloxacin Degradation. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 395, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Tang, L.; Wang, J.; Yu, J.; Zhang, H.; Yu, M.; Zou, J.; Xie, Q. Egg Shell Biochar-Based Green Catalysts for the Removal of Organic Pollutants by Activating Persulfate. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 745, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, D.; Chen, Y.; Yan, J.; Qian, L.; Han, L.; Chen, M. Activation Mechanism of Peroxymonosulfate by Biochar for Catalytic Degradation of 1, 4-Dioxane: Important Role of Biochar Defect Structures. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 370, 614–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Su, C.; Miao, J.; Zhong, Y.; Shao, Z.; Wang, S.; Sun, H. Insights Into Perovskite-Catalyzed Peroxymonosulfate Activation: Maneuverable Cobalt Sites for Promoted Evolution of Sulfate Radicals. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 220, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yang, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Xian, J.; Li, T.; Pu, Y.; Zhou, W.; et al. Rape Straw Supported FeS Nanoparticles with Encapsulated Structure as Peroxymonosulfate and Hydrogen Peroxide Activators for Enhanced Oxytetracycline Degradation. Molecules 2023, 28, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.; Wei, J.; Xu, M.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Cui, N.; Li, J.; Wang, Z. Insight Into Boron-Doped Biochar as Efficient Metal-Free Catalyst for Peroxymonosulfate Activation: Important Role of-OBO-Moieties. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 445, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, X.; Zhu, C.; Chou, Y.; Zhong, M.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, Q. Persulfate Activation Via Nanoscale Zero-Valent Iron Based Biochar for Oxytetracycline Degradation. Environ. Eng. 2022, 40, 118–124. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, M.; Li, M.; Zhang, Q.; Abodif, A.M.; Peng, H.; Xia, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, Y. Exploration of Oxytetracycline Degradation Via Co/Fe Composites: Advantages of Bimetal for the Contribution Deviation of Reactive Oxygen Species and the Corresponding Lifetime Extension. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 382, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Bao, J.; Huang, Y.; Xiang, L.; Faheem; Ren, B.; Du, J.; Nadagouda, M.N.; Dionysiou, D.D. Efficient Degradation of Atrazine with Porous Sulfurized Fe2O3 as Catalyst for Peroxymonosulfate Activation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 259, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Guo, W.; Wang, H.; Si, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Luo, H.; Ren, N. Activation of Peroxymonosulfate by Cobalt-Impregnated Biochar for Atrazine Degradation: The Pivotal Roles of Persistent Free Radicals and Ecotoxicity Assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 398, 756–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huong, P.T.; Jitae, K.; Al Tahtamouni, T.; Tri, N.L.M.; Kim, H.-H.; Cho, K.H.; Lee, C. Novel Activation of Peroxymonosulfate by Biochar Derived from Rice Husk Toward Oxidation of Organic Contaminants in Wastewater. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 33, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Chen, S.; Zhou, M.; Li, M.; Lan, S.; Feng, T. Highly Efficient Cobalt-Based Amorphous Catalyst for Peroxymonosulfate Activation Toward Wastewater Remediation. Rare Met. 2023, 42, 1160–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Dong, W.; Wang, H.; Ma, H.; Liu, P.; Gu, Y.; Fan, H.; Song, X. Degradation of Tetrabromobisphenol A by Ozonation: Performance, Products, Mechanism and Toxicity. Chemosphere 2019, 235, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Qian, S.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, J.; Shen, S.; Tang, J.; Ding, Y.; Zhi, S.; Zhang, K.; Yang, L.; et al. Efficient Degradation of Sulfamethoxazole in Various Waters with Peroxymonosulfate Activated by Magnetic-Modified Sludge Biochar: Surface-Bound Radical Mechanism. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 319, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Xiao, Y.; Tang, J.; Chen, H.; Sun, H. Persulfate Activation with Sawdust Biochar in Aqueous Solution by Enhanced Electron Donor-Transfer Effect. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 690, 768–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Guo, Q.; Liu, X.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, W.; Tang, S.; Lee, H.K. Interlayer Nanoconfinement Enhanced Peroxymonosulfate Activation for Nanozyme-Mediated Colorimetric Detection. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 14666–14674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wan, J.; Ma, Y. Reduced Graphene Oxide-Supported Metal Organic Framework as A Synergistic Catalyst for Enhanced Performance on Persulfate Induced Degradation of Trichlorophenol. Chemosphere 2020, 240, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wen, L.; Yu, C.; Li, S.; Tang, J. Activation of Peroxymonosulfate by MnFe2O4@BC Composite for Bisphenol A Degradation: The Coexisting of Free-Radical and Non-Radical Pathways. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 442, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Wang, G.; Tan, M.; Yuan, J. A Europium (III) Complex as An Efficient Singlet Oxygen Luminescence Probe. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 13442–13450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Huang, Y.; Fang, C.; Xue, Y.; Ai, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z. Peroxymonosulfate/Base Process in Saline Wastewater Treatment: The Fight Between Alkalinity and Chloride Ions. Chemosphere 2018, 199, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Jiang, J.; Gao, Y.; Ma, J.; Pang, S.-Y.; Li, J.; Lu, X.-T.; Yuan, L.-P. Activation of Peroxymonosulfate by Benzoquinone: A Novel Nonradical Oxidation Process. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 12941–12950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

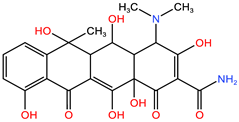

| Molecular Formula | Molecular Weight | Solubility/(mg/L) | Molecular Structure | pKa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OTC | C22H24N2O9 | 460.434 | 200 |  | pKa1 = 3.57 pKa2 = 7.49 pKa3 = 9.44 |

| Kind of Biochar | Specific Surface Area (m2/g) | Overall Pore Volume (cm3/g) | Average Aperture (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MBC600 | 1.850 | 9.732 × 10−3 | 21.0376 |

| Co15-MBC400 | 5.894 | 2.12 × 10−2 | 14.3868 |

| Co15-MBC600 | 308.832 | 1.682 × 10−1 | 1.97816 |

| Co15-MBC800 | 600.530 | 2.703 × 10−1 | 1.80059 |

| Biochar | Materials | Pollutants | Concentration (mg/L) | Removal Rate | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RS-FeS | Rapeseed straw | OTC | 20 | 84% | [23] |

| TBC | Tea seed shell | OTC | 20 | 91% | [24] |

| xnZVI-BC | Tea seed shell | OTC | 20 | 70% | [25] |

| PWBC | Pine wood | OTC | 20 | 71% | [26] |

| PNBC | Pine needle | OTC | 20 | 82% | [27] |

| Co15-MBC600 | Macadamia nut shells | OTC | 20 | 95% | / |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, Y.; Wang, A.; Wu, Y.; Gu, L.; Liu, S.; Liu, G. Study on Degradation of Oxytetracycline in Water by PMS Activated by Modified Macadamia Nut Shell Biochar. Processes 2025, 13, 3867. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123867

Lu Y, Wang A, Wu Y, Gu L, Liu S, Liu G. Study on Degradation of Oxytetracycline in Water by PMS Activated by Modified Macadamia Nut Shell Biochar. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3867. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123867

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Yixin, Aojie Wang, Yi Wu, Linyun Gu, Shuyuan Liu, and Guo Liu. 2025. "Study on Degradation of Oxytetracycline in Water by PMS Activated by Modified Macadamia Nut Shell Biochar" Processes 13, no. 12: 3867. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123867

APA StyleLu, Y., Wang, A., Wu, Y., Gu, L., Liu, S., & Liu, G. (2025). Study on Degradation of Oxytetracycline in Water by PMS Activated by Modified Macadamia Nut Shell Biochar. Processes, 13(12), 3867. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123867