Novel Process Configuration of Photobioreactor and Supercritical Water Oxidation for Energy Production from Microalgae

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

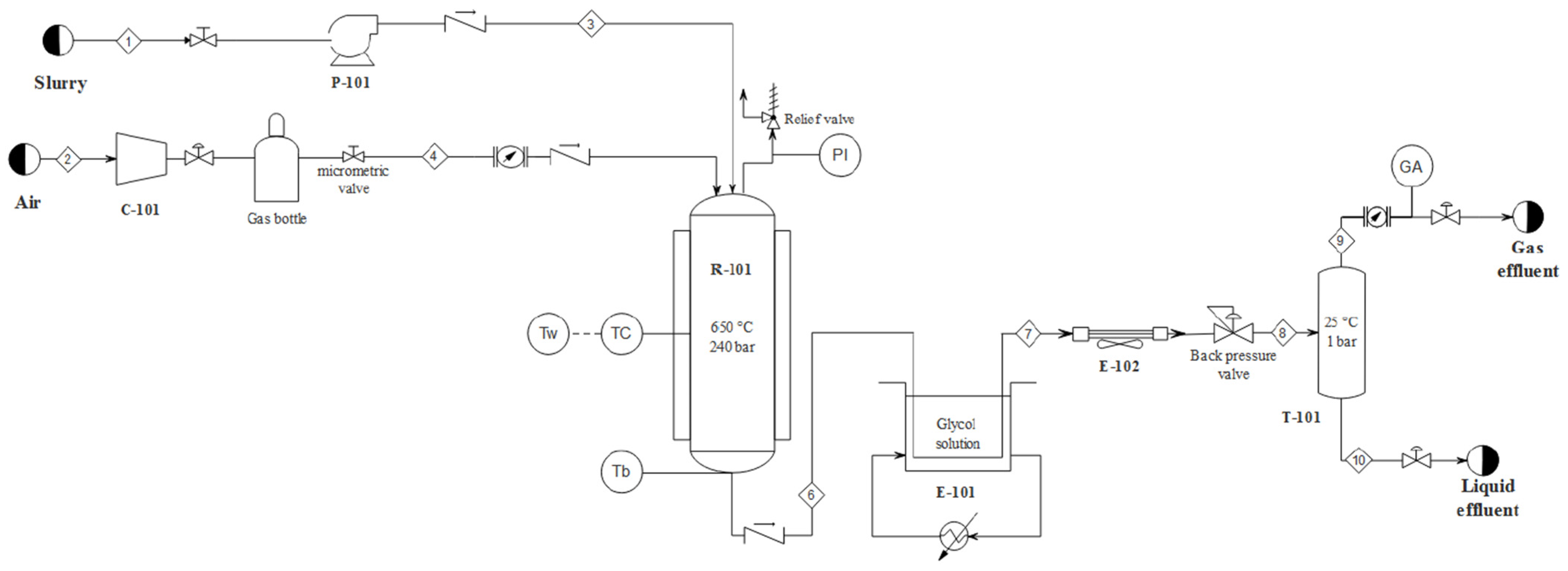

3.1. Experimental Results

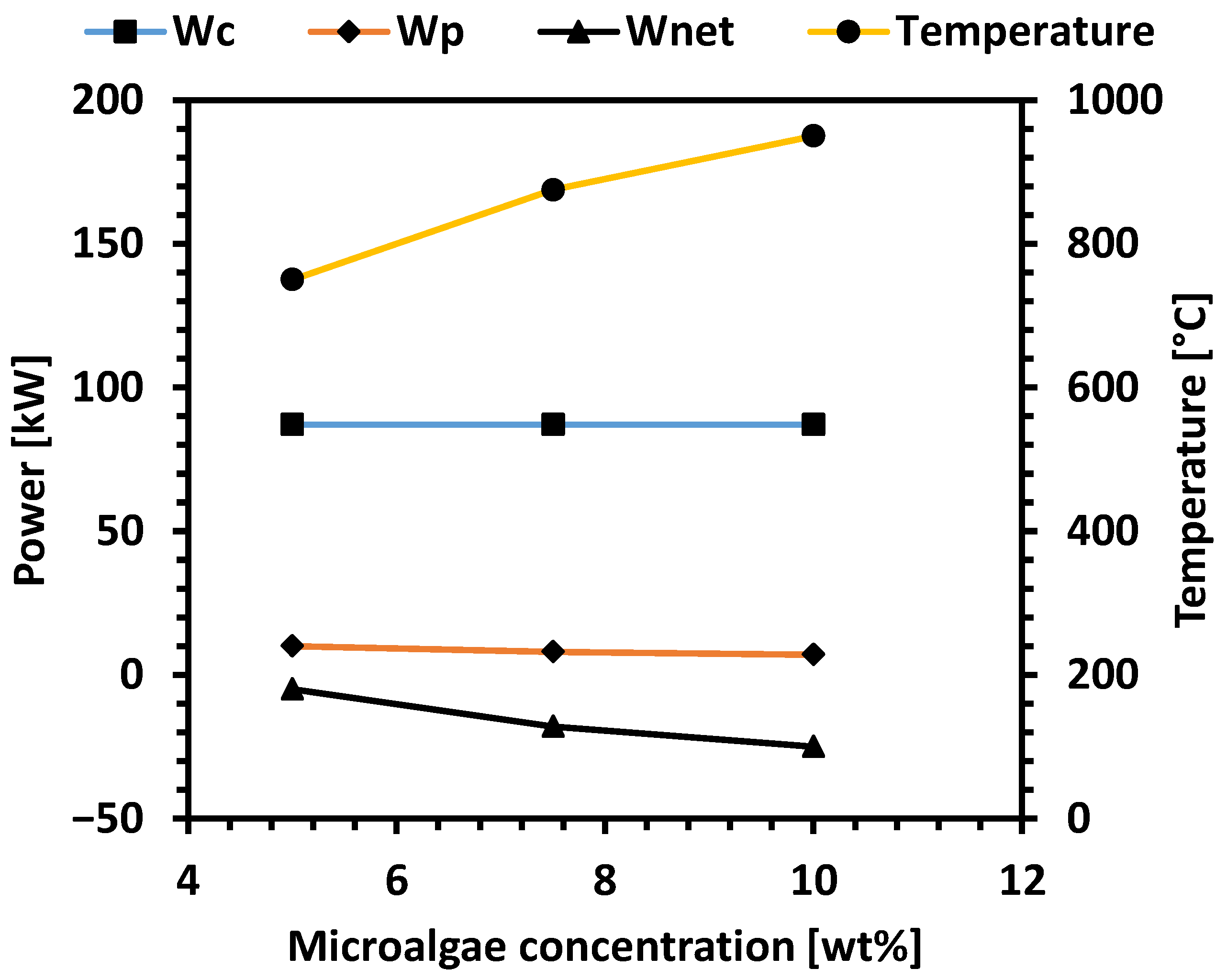

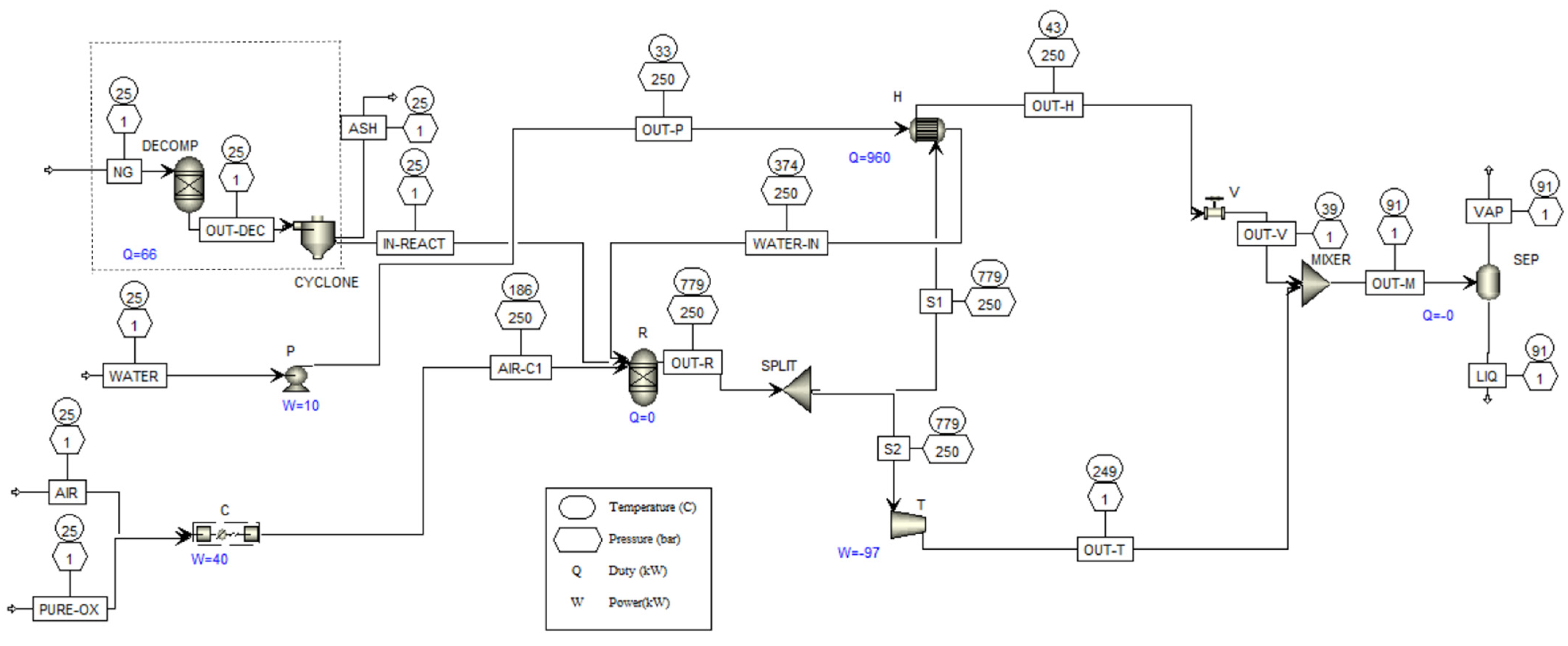

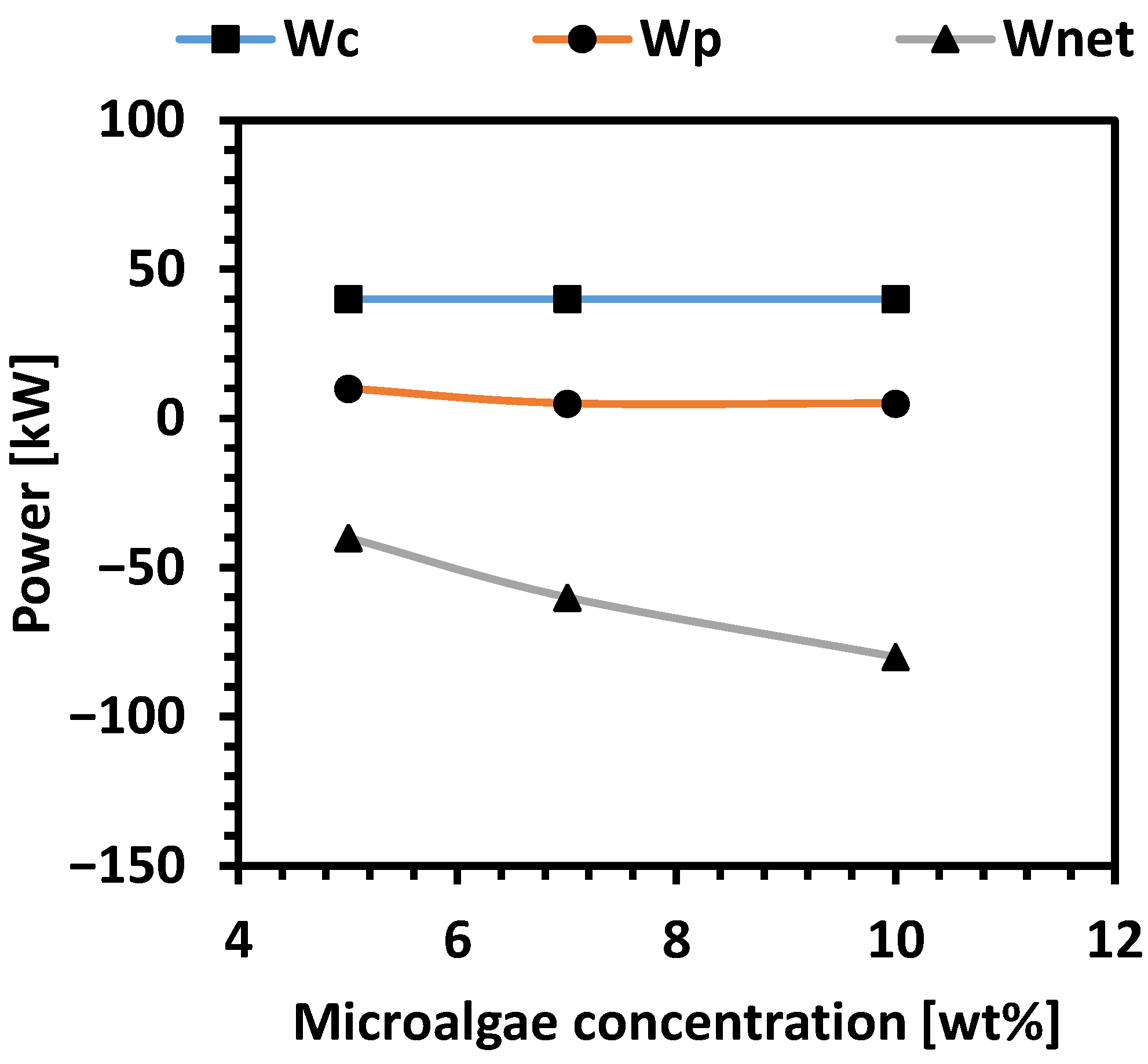

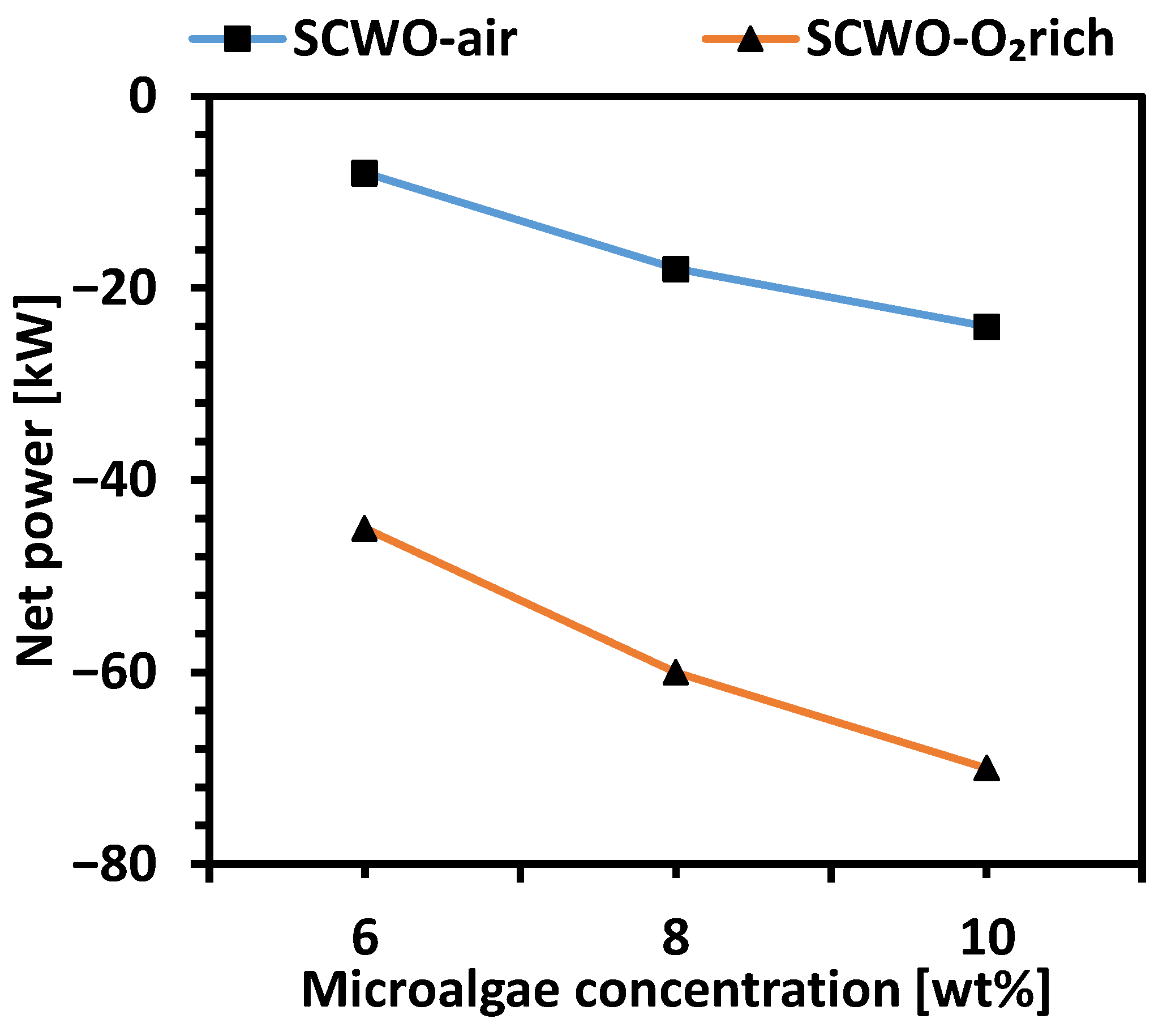

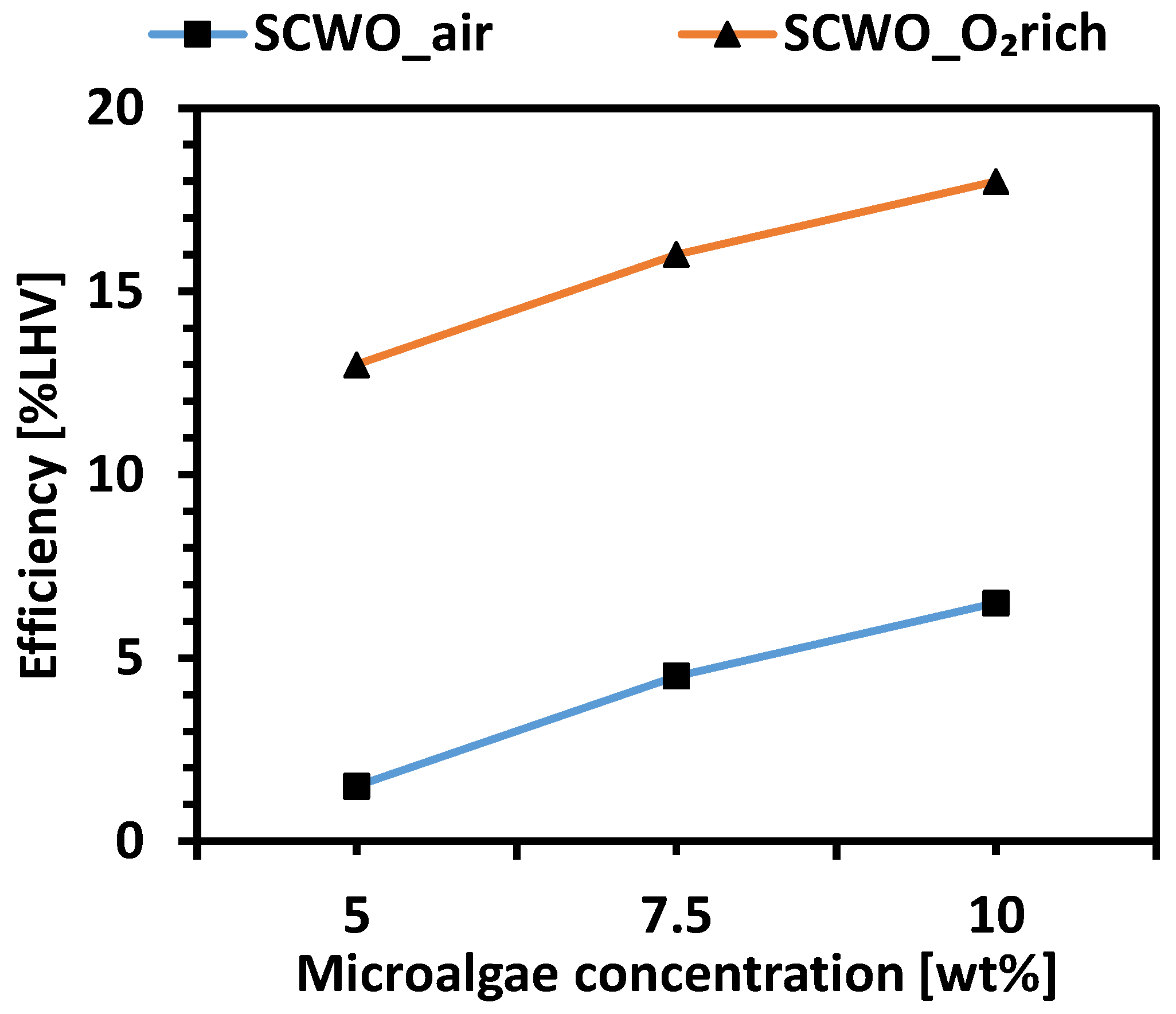

3.2. Process Simulation Results

4. Discussion

- -

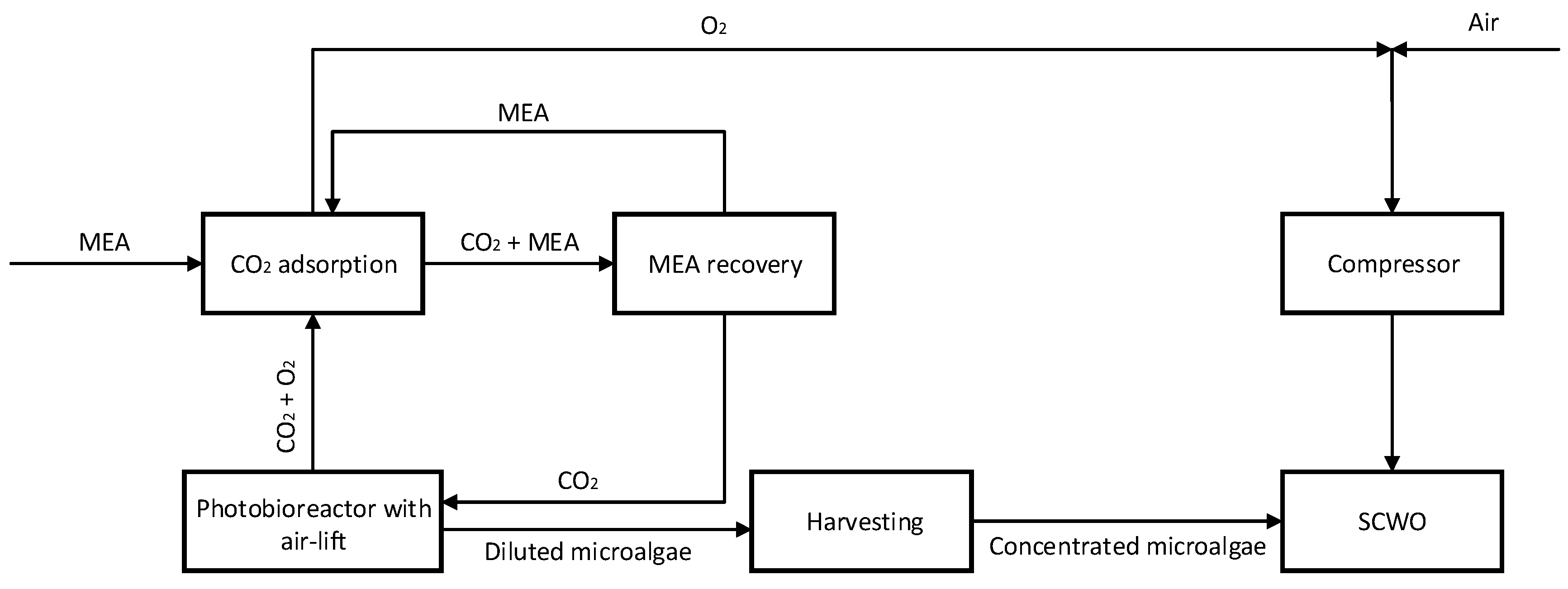

- External loop air-lift section: In the riser, the liquid stream exiting the photobioreactor ascends together with a CO2 gas flow introduced through an appropriate sparger. Gas–liquid separation occurs in the degasser, after which the gas-free liquid descends through the downcomer and is recirculated to the photobioreactor tubes.

- -

- CO2 recovery/recycle section: The low-pressure gas stream exiting the air-lift degasser consists primarily of CO2, O2, and water vapor. This stream is introduced at the bottom of a packed absorption tower, while an MEA–water solution is fed from the top. Oxygen passes through the column and is withdrawn at the top using a vacuum pump. The CO2-rich solvent is then directed to solar thermal panels, where it is heated to approximately 100 °C; at this temperature, the absorbed CO2 is released at a pressure adequate for recycling back to the air-lift after cooling. The regenerated hot MEA-H2O solution is subsequently cooled and returned to the CO2 absorption tower.

- -

- O2-rich stream: an almost pure oxygen stream is recovered at the outlet of the vacuum pump. This oxygen can be considered a valuable co-product of microalgae cultivation, with production rates on the order of 1 kg O2 per kilogram of algal biomass. The purified oxygen stream can then be directed to the compressor for use in the SCWO process.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SCWO | Supercritical Water Oxidation |

| FAME | Fatty Acid Methyl Ester |

| SCWG | Supercritical Water Gasification |

| TOC | Total Organic Carbon |

| LHV | Low Heating Value |

| HCD | High Cell Density |

| MEA | Mono-Ethanolamine |

| TFF | Tangential Flow Filtration |

References

- Gouveia, L. Microalgae as a Feedstock for Biofuels; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; ISBN 978-3-642-17996-9. [Google Scholar]

- Morillas-España, A.; Pérez-Crespo, R.; Villaró-Cos, S.; Rodríguez-Chikri, L.; Lafarga, T. Integrating Microalgae-Based Wastewater Treatment, Biostimulant Production, and Hydroponic Cultivation: A Sustainable Approach to Water Management and Crop Production. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1364490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutzu, G.A.; Usai, L.; Ciurli, A.; Chiellini, C.; Di Caprio, F.; Pagnanelli, F.; Parsaeimehr, A.; Malina, I.; Malins, K.; Cosenza, B.; et al. Bio-Jet Fuels from Photosynthetic Microorganisms: A Focus on Downstream Processes. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 201, 107833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Das, P.; Abdul Quadir, M.; Thaher, M.I.; Mahata, C.; Sayadi, S.; Al-Jabri, H. Microalgal Feedstock for Biofuel Production: Recent Advances, Challenges, and Future Perspective. Fermentation 2023, 9, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moioli, E.; Schildhauer, T. Negative CO2 Emissions from Flexible Biofuel Synthesis: Concepts, Potentials, Technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 158, 112120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephy, G.M.; Surendarnath, S.; Flora, G.; Amesho, K.T.T. Microalgae for Sustainable Biofuel Generation: Innovations, Bottlenecks, and Future Directions. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2025, 34, e70019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Ning, R.; Zhang, M.; Deng, X. Biofuel Production as a Promising Way to Utilize Microalgae Biomass Derived from Wastewater: Progress, Technical Barriers, and Potential Solutions. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1250407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhokane, D.; Shaikh, A.; Yadav, A.; Giri, N.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Dasgupta, S.; Bhadra, B. CRISPR-Based Bioengineering in Microalgae for Production of Industrially Important Biomolecules. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1267826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naduthodi, M.I.S.; Südfeld, C.; Avitzigiannis, E.K.; Trevisan, N.; van Lith, E.; Alcaide Sancho, J.; D’Adamo, S.; Barbosa, M.; van der Oost, J. Comprehensive Genome Engineering Toolbox for Microalgae Nannochloropsis Oceanica Based on CRISPR-Cas Systems. ACS Synth. Biol. 2021, 10, 3369–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.K.; Jaryal, S.; Sharma, S.; Dhyani, A.; Tewari, B.S.; Mahato, N. Biofuels from Microalgae: A Review on Microalgae Cultivation, Biodiesel Production Techniques and Storage Stability. Processes 2025, 13, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Dunford, N.T. Algae: Nature’s Renewable Resource for Fuels and Chemicals. Biomass 2024, 4, 329–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshandeh, M. Microalgae as a Source for Bioenergy: A Search for an Energy-Efficient Process. Bioenergy Res. 2023, 16, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Guerra, E.; Gnaneswar Gude, V. Energy Aspects of Microalgal Biodiesel Production. AIMS Energy 2016, 4, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falfushynska, H. Advancements and Prospects in Algal Biofuel Production: A Comprehensive Review. Phycology 2024, 4, 548–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina Grima, E.; Belarbi, E.-H.; Acién Fernández, F.G.; Robles Medina, A.; Chisti, Y. Recovery of Microalgal Biomass and Metabolites: Process Options and Economics. Biotechnol. Adv. 2003, 20, 491–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeevanandam, J.; Harun, M.R.; Lau, S.Y.; Sewu, D.D.; Danquah, M.K. Microalgal Biomass Generation via Electroflotation: A Cost-Effective Dewatering Technology. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, S.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, B. Supercritical Water Gasification and Partial Oxidation of Municipal Sewage Sludge: An Experimental and Thermodynamic Study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Niu, Q.; Ma, L.; Derese, S.; Verliefde, A.; Ronsse, F. Complete Oxidation of Organic Waste under Mild Supercritical Water Oxidation by Combining Effluent Recirculation and Membrane Filtration. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 736, 139731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinizand, H.; Lim, C.J.; Webb, E.; Sokhansanj, S. Economic Analysis of Drying Microalgae Chlorella in a Conveyor Belt Dryer with Recycled Heat from a Power Plant. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 124, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, Y.; Wu, N.; Lan, C.Q. CO2 Bio-Mitigation Using Microalgae. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 79, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosenza, A.; Lima, S.; Gurreri, L.; Mancini, G.; Scargiali, F. Microalgae in the Mediterranean Area: A Geographical Survey Outlining the Diversity and Technological Potential. Algal. Res. 2024, 82, 103669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handbook of Microalgal Culture; Richmond, A., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; ISBN 9780632059539. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner, G. Near Critical and Supercritical Water. Part I. Hydrolytic and Hydrothermal Processes. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2009, 47, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelechi, F.M.; Aribisala, A.A. Thermochemical Conversion of Microalgae: Challenges and Prospective of HTL Pathway for Algae Biorefinery. In Proceedings of the SPE Nigeria Annual International Conference and Exhibition, Lagos, Nigeria, 3–5 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bagchi, S.K.; Patnaik, R.; Prasad, R. Feasibility of Utilizing Wastewaters for Large-Scale Microalgal Cultivation and Biofuel Productions Using Hydrothermal Liquefaction Technique: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 651138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Cui, Z.; Mallick, K.; Nirmalakhandan, N.; Brewer, C.E. Hydrothermal Liquefaction of High- and Low-Lipid Algae: Mass and Energy Balances. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 258, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.H.; Quinn, J.C. Microalgae to Biofuels through Hydrothermal Liquefaction: Open-Source Techno-Economic Analysis and Life Cycle Assessment. Appl. Energy 2021, 289, 116613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Mofijur, M.; Uddin, M.N.; Kabir, Z.; Badruddin, I.A.; Khan, T.M.Y. Insights into Anaerobic Digestion of Microalgal Biomass for Enhanced Energy Recovery. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1355686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdalena, J.A.; Ballesteros, M.; González-Fernandez, C. Efficient Anaerobic Digestion of Microalgae Biomass: Proteins as a Key Macromolecule. Molecules 2018, 23, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.D.; Drosg, B.; Allen, E.; Jerney, J.; Xia, A.; Herrmann, C. A Perspective on Algal Biogas; IEA Bioenergy: Paris, France, 2015; ISBN 9781910154182. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Zhao, F.; Su, X. Direct Extraction of Lipids from Wet Microalgae Slurries by Super-High Hydrostatic Pressure. Algal. Res. 2021, 58, 102412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, K.; Keshavarz Moraveji, M.; Abedini Najafabadi, H. A Review on Bio-Fuel Production from Microalgal Biomass by Using Pyrolysis Method. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 3046–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeley, K.; Orozco, R.L.; Macaskie, L.E.; Love, J.; Al-Duri, B. Supercritical Water Gasification of Microalgal Biomass for Hydrogen Production—A Review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 310–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stucki, S.; Vogel, F.; Ludwig, C.; Haiduc, A.G.; Brandenberger, M. Catalytic Gasification of Algae in Supercritical Water for Biofuel Production and Carbon Capture. Energy Environ. Sci. 2009, 2, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haiduc, A.G.; Brandenberger, M.; Suquet, S.; Vogel, F.; Bernier-Latmani, R.; Ludwig, C. SunCHem: An Integrated Process for the Hydrothermal Production of Methane from Microalgae and CO2 Mitigation. J. Appl. Phycol. 2009, 21, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.M.; Duan, P.; Savage, P.E. Hydrothermal Liquefaction and Gasification of Nannochloropsis sp. Energy Fuels 2010, 24, 3639–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Q.; Savage, P.E.; Wei, C. Gasification of Alga Nannochloropsis sp. in Supercritical Water. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2012, 61, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, G.; Dispenza, M.; Rubio, P.; Scargiali, F.; Marotta, G.; Brucato, A. Supercritical Water Gasification of Microalgae and Their Constituents in a Continuous Reactor. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2016, 118, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakinala, A.G.; Brilman, D.W.F. (Wim); van Swaaij, W.P.M.; Kersten, S.R.A. Catalytic and Non-Catalytic Supercritical Water Gasification of Microalgae and Glycerol. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2010, 49, 1113–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurdiawati, A.; Zaini, I.N.; Irhamna, A.R.; Sasongko, D.; Aziz, M. Novel Configuration of Supercritical Water Gasification and Chemical Looping for Highly-Efficient Hydrogen Production from Microalgae. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 112, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M. Integrated Supercritical Water Gasification and a Combined Cycle for Microalgal Utilization. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 91, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adar, E.; Ince, M.; Bilgili, M.S. Evaluation of Development in Supercritical Water Oxidation Technology. Desalination Water Treat 2019, 161, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo, M.D.; Cocero, M.J. Destruction of an Industrial Wastewater by Supercritical Water Oxidation in a Transpiring Wall Reactor. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 137, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killilea, W.R.; Swallow, K.C.; Hong, G.T. The Fate of Nitrogen in Supercritical-Water Oxidation. J. Supercrit. Fluids 1992, 5, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanmore, B.R. The Formation of Dioxins in Combustion Systems. Combust. Flame 2004, 136, 398–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affolter, J.; Brunner, T.; Hagger, N.; Vogel, F. A Prototype System for the Hydrothermal Oxidation of Feces. Water Res. X 2022, 17, 100160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocero, M.J.; Alonso, E.; Sanz, M.T.; Fdz-Polanco, F. Supercritical Water Oxidation Process under Energetically Self-Sufficient Operation. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2002, 24, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rodríguez, Y.; Mato, F.A.; Martín, A.; Bermejo, M.D.; Cocero, M.J. Energy Recovery from Effluents of Supercritical Water Oxidation Reactors. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2015, 104, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshangana, C.S.; Nhlengethwa, S.T.; Glass, S.; Denison, S.; Kuvarega, A.T.; Nkambule, T.T.I.; Mamba, B.B.; Alvarez, P.J.J.; Muleja, A.A. Technology Status to Treat PFAS-Contaminated Water and Limiting Factors for Their Effective Full-Scale Application. NPJ Clean Water 2025, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, M.J.; Thoma, E.; Sahle-Damesessie, E.; Crone, B.; Whitehill, A.; Shields, E.; Gullett, B. Supercritical Water Oxidation as an Innovative Technology for PFAS Destruction. J. Environ. Eng. 2022, 148, 05021006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Chen, J.; Su, C.; Ma, C. Energy Consumption and Economic Analyses of a Supercritical Water Oxidation System with Oxygen Recovery. Processes 2018, 6, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Duan, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, F.; Li, J.; Dai, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. Supercritical Water Oxidation for the Treatment and Utilization of Organic Wastes: Factor Effects, Reaction Enhancement, and Novel Process. Environ. Res. 2024, 251, 118571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo, M.D.; Cocero, M.J. Supercritical Water Oxidation: A Technical Review. AIChE J. 2006, 52, 3933–3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Silva, L.; López-González, D.; Garcia-Minguillan, A.M.; Valverde, J.L. Pyrolysis, Combustion and Gasification Characteristics of Nannochloropsis Gaditana Microalgae. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 130, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKendry, P. Energy Production from Biomass (Part 2): Conversion Technologies. Bioresour. Technol. 2002, 83, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varfolomeev, S.D.; Wasserman, L.A. Microalgae as Source of Biofuel, Food, Fodder, and Medicines. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2011, 47, 789–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotta, G.; Scargiali, F.; Lima, S.; Caputo, G.; Grisafi, F.; Brucato, A. Vacuum Air-Lift Bioreactor for Microalgae Production. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2017, 57, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weschler, M.K.; Barr, W.J.; Harper, W.F.; Landis, A.E. Process Energy Comparison for the Production and Harvesting of Algal Biomass as a Biofuel Feedstock. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 153, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Technology | Operating Conditions | Efficiency | Advantages | Disadvantages | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrothermal Liquefaction (HTL) | 280–350 °C, 10–20 MPa | Variable (35–60% with energy recovery) | Low temperature, low corrosion, handles wet biomass | Lower conversion rates, produces aqueous byproducts, and complex downstream processing | [25,26,27] |

| Anaerobic Digestion (AD) | 35–40 °C, ambient pressure | ~25–35% (Biogas efficiency) | Low temperature, simple technology, biosolids recovery | Slow kinetics (30–60 days retention), lower energy density output, and methane emissions | [28,29,30] |

| Lipid Extraction + Biodiesel | 25–100 °C, ambient pressure | ~25–35% (Biodiesel efficiency) | Established technology, food-grade glycerol byproduct | Requires drying (68% of energy cost), low lipid content in many species, and only works for lipid-rich strains | [31] |

| Direct Combustion | 850–1000 °C, ambient pressure | ~30% (Thermal efficiency) | Simple technology, immediate energy recovery | High moisture content (70–90%), low energy density requiring drying, and dust generation | [32] |

| Classic Gasification | 700–900 °C, ambient pressure | ~35–40% (Syngas efficiency) | Produces syngas for flexible use, with lower drying requirements | Incomplete conversion, tar formation, and complex gas cleanup systems | [32] |

| Main Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Dry mass, wt% | 95 |

| Key component | C9H16NO4 |

| Cells average diameter | 2–3 μm (sphere shaped) |

| Lower heating value, LHV [MJ/kg] | 20 |

| Composition, wt% | |

| Proteins | 38 |

| Lipids | 32 |

| Carbohydrates | 12 |

| Ash 1 | 14 |

| Microalgae Slurry Concentration | Residence Time [min] | Slurry Flow Rate [mL/min] | Air Flow Rate [g/min] | TOC Removal, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt% | TOC [mg/L] | ||||

| 1.0 | 4633 | 5 | 6.1 | 0.48 | 99.996 ± 0.083 |

| 1.0 | 4633 | 3 | 10.2 | 0.80 | 99.995 ± 0.083 |

| 1.0 | 4633 | 1 | 30.7 | 2.40 | 99.990 ± 0.061 |

| 0.5 | 2316 | 5 | 6.3 | 0.25 | 99.982 ± 0.087 |

| 0.5 | 2316 | 3 | 10.5 | 0.41 | 99.986 ± 0.087 |

| 0.5 | 2316 | 1 | 31.5 | 1.24 | 99.955 ± 0.061 |

| 0.057 | 264 | 5 | 6.5 | 0.03 | 97.100 ± 0.042 |

| 0.057 | 264 | 3 | 10.8 | 0.05 | 95.500 ± 0.041 |

| 0.057 | 264 | 1 | 32.4 | 0.15 | 94.400 ± 0.038 |

| NG | AIR-C | WATER-IN | OUT-DEC | IN-REACT | OUT-R | S1 | S2 | OUT-M | VAP | LIQ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Flow (kg/min) | 1 | 6.33 | 23.47 | 1 | 0.93 | 30.73 | 23.76 | 6.98 | 30.73 | 11.14 | 19.59 |

| Mass Enthalpy (kW) | 118 | 17 | 4976 | 52 | −51 | 5010 | 3873 | 1137 | 6334 | 1240 | 5094 |

| N2 (kg/min) | 0 | 4.85 | 0 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 4.91 | 3.79 | 1.12 | 4.91 | 4.90 | 0.01 |

| WATER (kg/min) | 0 | 0 | 23.47 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 24.2 | 18.71 | 5.49 | 24.2 | 4.65 | 19.50 |

| O2 (kg/min) | 0 | 1.47 | 0 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0 |

| S (kg/min) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| H2 (kg/min) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cl2 (kg/min) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| HCl (kg/min) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0 |

| CO2 (kg/min) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.45 | 1.12 | 0.33 | 1.45 | 1.43 | 0.02 |

| Sulf. Acid (kg/min) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.01 |

| ASH (kg/min) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.07 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mass vapor fraction | - | 1 | 0 | 0.35 | 0.38 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.36 | 1 | 0 |

| Mass solid fraction | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.46 | 0.42 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| T (°C) | 25 | 187.3 | 385 | 25 | 25 | 686 | 686 | 686 | 686 | 83.6 | 83.6 |

| P (bar) | 1 | 250 | 250 | 1 | 1 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 1 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cosenza, A.; Lima, S.; Scargiali, F.; Grisafi, F.; Caputo, G. Novel Process Configuration of Photobioreactor and Supercritical Water Oxidation for Energy Production from Microalgae. Processes 2025, 13, 3860. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123860

Cosenza A, Lima S, Scargiali F, Grisafi F, Caputo G. Novel Process Configuration of Photobioreactor and Supercritical Water Oxidation for Energy Production from Microalgae. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3860. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123860

Chicago/Turabian StyleCosenza, Alessandro, Serena Lima, Francesca Scargiali, Franco Grisafi, and Giuseppe Caputo. 2025. "Novel Process Configuration of Photobioreactor and Supercritical Water Oxidation for Energy Production from Microalgae" Processes 13, no. 12: 3860. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123860

APA StyleCosenza, A., Lima, S., Scargiali, F., Grisafi, F., & Caputo, G. (2025). Novel Process Configuration of Photobioreactor and Supercritical Water Oxidation for Energy Production from Microalgae. Processes, 13(12), 3860. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123860