Identification and Evaluation of Fracturing Advantageous Lithofacies in the Main Structural Zone of Yingxiongling, Qaidam Basin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Reservoir Characteristics

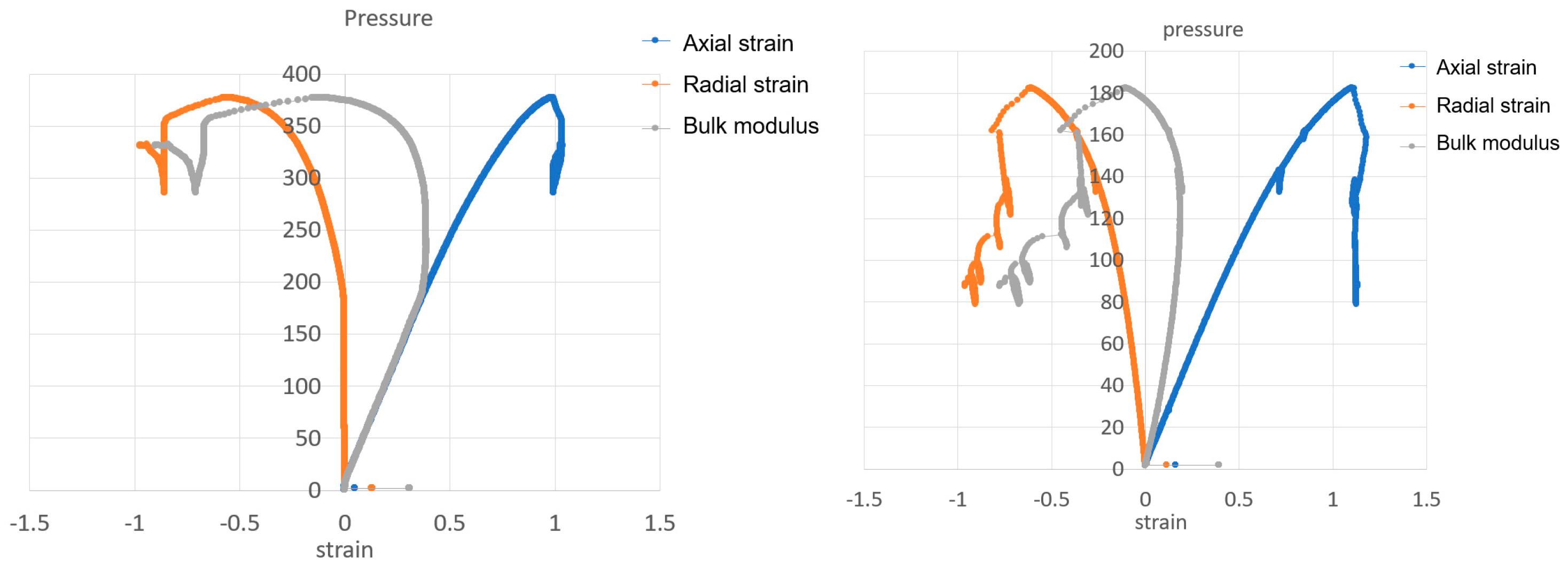

2.1. Rock Mechanismcs Experiments

2.2. Fracture Characterisation

2.3. Porosity and Oil-Bearing Potential

3. Prodcution Analysis

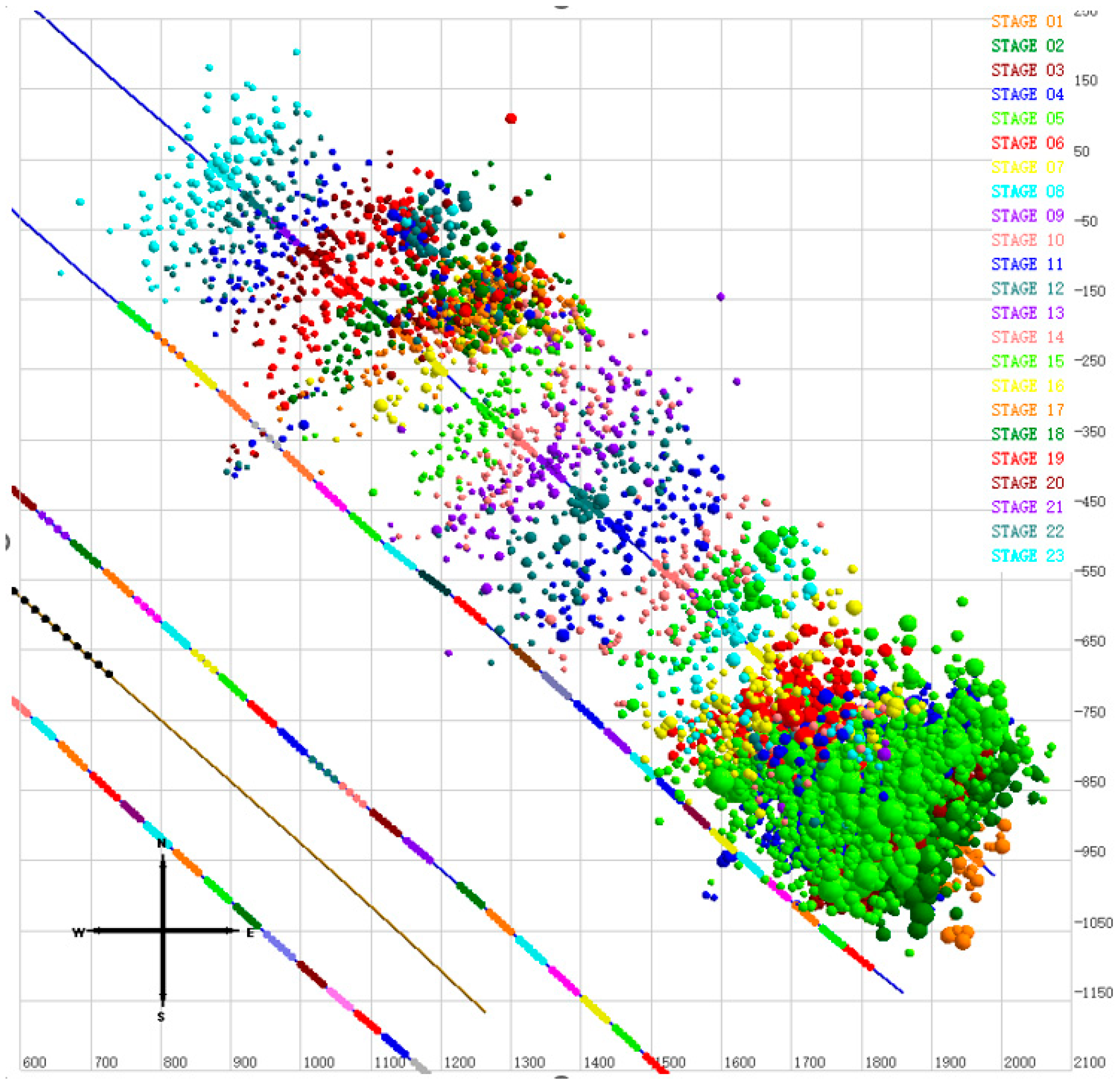

3.1. Microseismic Evaluation

3.1.1. Methods

3.1.2. Example

3.2. Fracturing Curve Analysis

4. Conclusions

- Laminated limy dolostone exhibits superior oil-bearing potential compared to layered dolomitic limestone, and demonstrates a clear tendency for preferential fracture propagation along bedding planes. Under equivalent stimulation conditions, this results in more uniformly distributed and extensively connected fracture networks with larger contact areas.

- Lithofacies exert a controlling influence on fracture mechanisms. While laminated dolomitic limestone shows higher mechanical strength, it develops less complex fracture networks than laminated shale. The former exhibits lower microseismic b-values, indicating shear-dominated failure along bedding planes, whereas the latter facilitates more complex network development through tensile failure.

- Integrated field diagnostics confirm higher complexity in laminated shale. Pressure decline analysis and microseismic monitoring consistently show that laminated shale produces fracture networks of greater complexity, making it more suitable for volume stimulation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hu, S.; Zhao, W.; Hou, L.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, R.; Wu, S.; Bai, B.; Jin, X. Development potential and technical strategy of continental shale oil in China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2020, 47, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, K.K.; Grieser, W.V.; Passman, A.; Tamayo, H.C.; Modeland, N.; Burke, B.E. A Completions Guide Book to Shale-Play Development: A Review of Successful Approaches Towards Shale-Play Stimulation in the Last Two Decades. In Proceedings of the Canadian Unconventional Resources and International Petroleum Conference, Calgary, AB, Canada, 19–21 October 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.A.; Paneitz, J.M.; Mullen, M.J.; Meijs, R.; Tunstall, K.M.; Garcia, M. The Successful Application of a Compartmental Completion Technique Used to Isolate Multiple Hydraulic-Fracture Treatments in Horizontal Bakken Shale Wells in North Dakota. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Denver, CO, USA, 21–24 September 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, C.; Li, G.; Li, C.; Shen, Y.; Ge, H.; Wen, H.; Lei, Z. Key Evaluation Aspects for Economic Development of Continental Shale Oil. Earth Sci. 2023, 48, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.Y.; Lei, Z.D.; Li, J.; Han, H. Progress in technology for the development of continental shale oil and thoughts on the development of scale benefits and strategies. J. China Univ. Pet. (Ed. Nat. Sci.) 2023, 47, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoback, M.D. Reservoir Geomechanics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; pp. 84–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.P.; Gale, J.F.W. Screening Criteria for Shale-Gas Systems. Gulf Coast Assoc. Geol. Soc. Trans. 2009, 59, 779–793. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, R. Effect of Rock Formation Properties on Vertical Propagation of Volume Fractures; China University of Petroleum: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wu, K.; Zhu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, S.; Chen, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xing, H.; Li, Y.; et al. Enrichment model and high-efficiency production of thick plateau mountainous shale oil reservoir: A case study of the Yingxiongling shale oil reservoir in Qaidam Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2023, 44, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cui, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, K.; Sheng, J.; Xian, C.; Liu, H. Geological characteristics and resource evaluation method for shale oil in a salinized lake basin: A case study from the upper member of the Lower Ganchaigou Formation in western Qaidam depression. Acta Geol. Sin. 2023, 97, 2425–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Kuang, L.; Wu, K.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, M.; Deng, L.; Lu, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q. Lithofacies characteristics and favorable source rock-reservoir combination of Yingxiongling shale in Qaidam Basin. China Pet. Explor. 2024, 29, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. Study on Rock Mechanical Properties and Fracability of Deep Shaleoil Reservoir; China University of Petroleum: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G.; Zhong, G.; Xie, B.; Huang, T. Petrophysical experiment-based logging evaluation method of shale brittleness. Nat. Gas Ind. 2014, 34, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Study on rock mechanical characteristics of Nantun Formation muddy sandstone reservoirs in Hailar Oilfield. Pet. Geol. Eng. 2012, 26, 107–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, E.; Bour, O.; Odling, N.E.; Davy, P.; Main, I.; Cowie, P.; Berkowitz, B. Scaling of fracture systems in geological media. Rev. Geophys. 2001, 39, 347–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahimi, M. Flow phenomena in rocks: From continuum models to fractals, percolation, cellular automata, and simulated annealing. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1993, 65, 1393–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, T. Fractal Analysis of Seepage Characteristics in Fractured Porous Media; Huazhong University of Science and Technology: Hubei, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, R.; Yang, Y.; Ju, Y.; Mao, L.; Yang, Y. Computation of fractal dimension of rock pores based on gray CT images. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2011, 56, 3346–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Peng, R.; Zhou, H. Computation of Fractal Dimension for Digital Image in a 3-D Space. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 2009, 38, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wu, X.; Duan, C.; Han, X.; Zhang, Y. CT scan-based quantitative characterization and fracability evaluation of fractures in shale reservoirs. Prog. Geophys. 2023, 38, 2147–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X. Research on Intelligent Extraction and Quantitative Characterization Method of Shale Fractures Based on CT Scanning; Chang’an University: Xi’an, China, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoback, M.D.; Kohli, A.H. Unconventional Reservoir Geomechanics: Shale Gas, Tight Oil, and Induced Seismicity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohmen, T.; Zhang, J.; Barker, L.; Blangy, J.P. Microseismic Magnitudes and b-Values for Delineating Hydraulic Fracturing and Depletion. SPE J. 2017, 22, 1624–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Wang, L.; Wu, S.; Pu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Liu, D. Application of pressure drop rate after fracturing in optimizing pump diameter of tubing pump in CBM wells: A case study of CBM wells in Southern Sichuan Basin. Drill. Prod. Technol. 2020, 43, 50–52+4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Sun, L.; Wang, P. Method for determining closure point in sand fracturing. Pet. Geol. Recovery Effic. 2009, 16, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lithofacy | Experimental Name | Number | Young’s Modulus (GPa) | Poisson’s Ratio | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Shear Modulus (MPa) | Bulk Modulus (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Layered dolomitic limestone | triaxial compression | Parallel 1 | 39.98 | 0.38 | 366.3 | 14.49 | 55.53 |

| Uniaxial compression | Parallel 2 | 36.81 | 0.39 | 97.8 | 13.24 | 55.77 | |

| Uniaxial compression | Vertical 1 | 21.96 | 0.33 | 86.6 | 8.26 | 21.53 | |

| Laminated limy dolostone. | triaxial compression | Parallel 1 | 36.77 | 0.37 | 189.9 | 13.42 | 47.14 |

| triaxial compression | Vertical 2 | 20.48 | 0.37 | 182.6 | 7.47 | 26.26 | |

| Uniaxial compression | Parallel 2 | 25.81 | 0.38 | 47.3 | 9.35 | 35.85 | |

| Uniaxial compression | Vertical 1 | 24.71 | 0.3 | 161.4 | 9.5 | 20.59 |

| Sample | Lithofacy | Fractal Dimension |

|---|---|---|

| Sample1-round | Laminated limy dolostone | 1.90 |

| Sample1-XZ | Laminated limy dolostone | 1.85 |

| Sample1-YZ | Laminated limy dolostone | 1.87 |

| Sample2-round | Layered dolomitic limestone | 1.94 |

| Sample2-XZ | Layered dolomitic limestone | 1.89 |

| Sample2-YZ | Layered dolomitic limestone | 1.90 |

| Stage | Lithofacy | S1 | TOC | POR/% | So/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | layered dolomitic limestone | 3.20 | 1.07 | 6.86 | 64.74 |

| 4 | 3.06 | 0.9 | 9.03 | 67.15 | |

| 15 | 1.72 | 0.56 | 4.32 | 43.52 | |

| 16 | 2.71 | 0.66 | 2.86 | 31.88 | |

| 17 | 4.14 | 0.7 | 3.81 | 38.52 | |

| 19 | 5.46 | 0.97 | 7.18 | 62.68 | |

| 20 | 4.16 | 0.68 | 4.75 | 48.57 | |

| 21 | 3.41 | 0.74 | 2.82 | 38.19 | |

| 22 | 16.34 | 1.04 | 2.94 | 50.98 | |

| 23 | 9.46 | 0.82 | 4.79 | 47.67 | |

| Average | 5.37 | 0.81 | 4.94 | 49.39 | |

| 1 | layered dolomitic limestone | 4.52 | 1.14 | 4.09 | 78.91 |

| 3 | 4.24 | 0.82 | 4.81 | 49.68 | |

| 5 | 2.89 | 0.72 | 5.37 | 49.00 | |

| 6 | 4.10 | 0.73 | 4.01 | 40.7 | |

| 7 | 2.20 | 0.65 | 3.51 | 34.77 | |

| 8 | 5.75 | 1.01 | 6.02 | 59.39 | |

| 9 | 6.51 | 0.92 | 4.66 | 54.06 | |

| 10 | 3.76 | 0.78 | 6.17 | 58.88 | |

| 11 | 4.37 | 0.98 | 6.77 | 64.04 | |

| 12 | 2.27 | 0.68 | 3.84 | 43.93 | |

| 13 | 1.80 | 0.51 | 4.29 | 41.18 | |

| 14 | 3.91 | 0.79 | 5.22 | 54.96 | |

| 18 | 6.00 | 1.14 | 3.95 | 56.42 | |

| Average | 4.02 | 0.84 | 4.82 | 52.76 | |

| Stage | Lithofacy | Aera/104 m3 | Range/m | b-Value | Stress Difference/MPa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | layered dolomitic limestone | 29.0213 | 35–225 | 1.965 | 15.54 |

| 16 | 35.8223 | 62–222 | 1.474 | 18.46 | |

| 17 | 54.1832 | 60–266 | 1.839 | 16.61 | |

| 19 | 59.9172 | 80–343 | 1.681 | 13.93 | |

| 20 | 47.0994 | 80–315 | 1.657 | 16.18 | |

| 21 | 47.0015 | 90–322 | 1.245 | 17.62 | |

| 22 | 68.995 | 88–324 | 1.039 | 17.39 | |

| 23 | 37.9177 | 95–288 | 1.435 | 15.27 | |

| Average | 47.49 | 1.542 | 16.37 | ||

| 7 | layered dolomitic limestone | 101.14 | 44–224 | 1.334 | 13.59 |

| 8 | 42.6421 | 20–177 | 1.793 | 10.95 | |

| 9 | 81.5146 | 10–192 | 1.129 | 10.60 | |

| 10 | 31.9155 | 0–200 | 1.892 | 13.20 | |

| 11 | 61.8999 | 5–175 | 1.101 | 11.31 | |

| 12 | 52.2583 | 5–261 | 1.264 | 16.15 | |

| 13 | 50.0467 | 14–350 | 1.424 | 13.92 | |

| 14 | 61.7795 | 20–224 | 1.389 | 13.28 | |

| 18 | 71.2732 | 61–322 | 1.648 | 13.53 | |

| Average | 61.60 | 1.441 | 12.95 |

| Stage | Lithofacy | Breakdown Pressure /MPa | Shut-In Pressure /MPa | Propagation Pressure /MPa | Shutdown Pressure Drop/MPa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | layered dolomitic limestone | 82.51 | 45.72 | 79.15 | −0.018 |

| 16 | 75.47 | 46.28 | 57.49 | −0.009 | |

| 17 | 75.67 | 45.23 | 74.31 | −0.011 | |

| 19 | 83.84 | 45.71 | 78.57 | −0.089 | |

| 20 | 82.04 | 46.65 | 77.03 | −0.007 | |

| 21 | 84.17 | 47 | 80.16 | −0.013 | |

| 22 | 82.94 | 47.08 | 79.47 | −0.007 | |

| 23 | 82.17 | 46.03 | 60.09 | −0.007 | |

| Average | 81.10 | 46.21 | 73.28 | −0.02 | |

| 7 | layered dolomitic limestone | 82.37 | 47.28 | 80.47 | −0.006 |

| 8 | 87.03 | 47.99 | 77.84 | −0.245 | |

| 9 | 84.39 | 47.38 | 73.99 | −0.006 | |

| 10 | 76.76 | 46.93 | 52.66 | −0.007 | |

| 11 | 82.62 | 47.08 | 72.1 | −0.007 | |

| 12 | 84.73 | 46.68 | 74.51 | −0.002 | |

| 13 | 77.05 | 46.21 | 74.2 | −0.007 | |

| 14 | 84.73 | 46.25 | 55.29 | −0.006 | |

| 18 | 79.56 | 45.69 | 78.04 | −0.002 | |

| Average | 82.14 | 46.83 | 71.01 | −0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yao, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, M. Identification and Evaluation of Fracturing Advantageous Lithofacies in the Main Structural Zone of Yingxiongling, Qaidam Basin. Processes 2025, 13, 3857. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123857

Yao Y, Shen Y, Zhang M, Zhang M. Identification and Evaluation of Fracturing Advantageous Lithofacies in the Main Structural Zone of Yingxiongling, Qaidam Basin. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3857. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123857

Chicago/Turabian StyleYao, Yuan, Yinghao Shen, Menglin Zhang, and Muyang Zhang. 2025. "Identification and Evaluation of Fracturing Advantageous Lithofacies in the Main Structural Zone of Yingxiongling, Qaidam Basin" Processes 13, no. 12: 3857. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123857

APA StyleYao, Y., Shen, Y., Zhang, M., & Zhang, M. (2025). Identification and Evaluation of Fracturing Advantageous Lithofacies in the Main Structural Zone of Yingxiongling, Qaidam Basin. Processes, 13(12), 3857. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123857