Development of a Chatbot for Pregnant Women on a Posyandu Application in Indonesia: From Qualitative Approach to Decision Tree Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

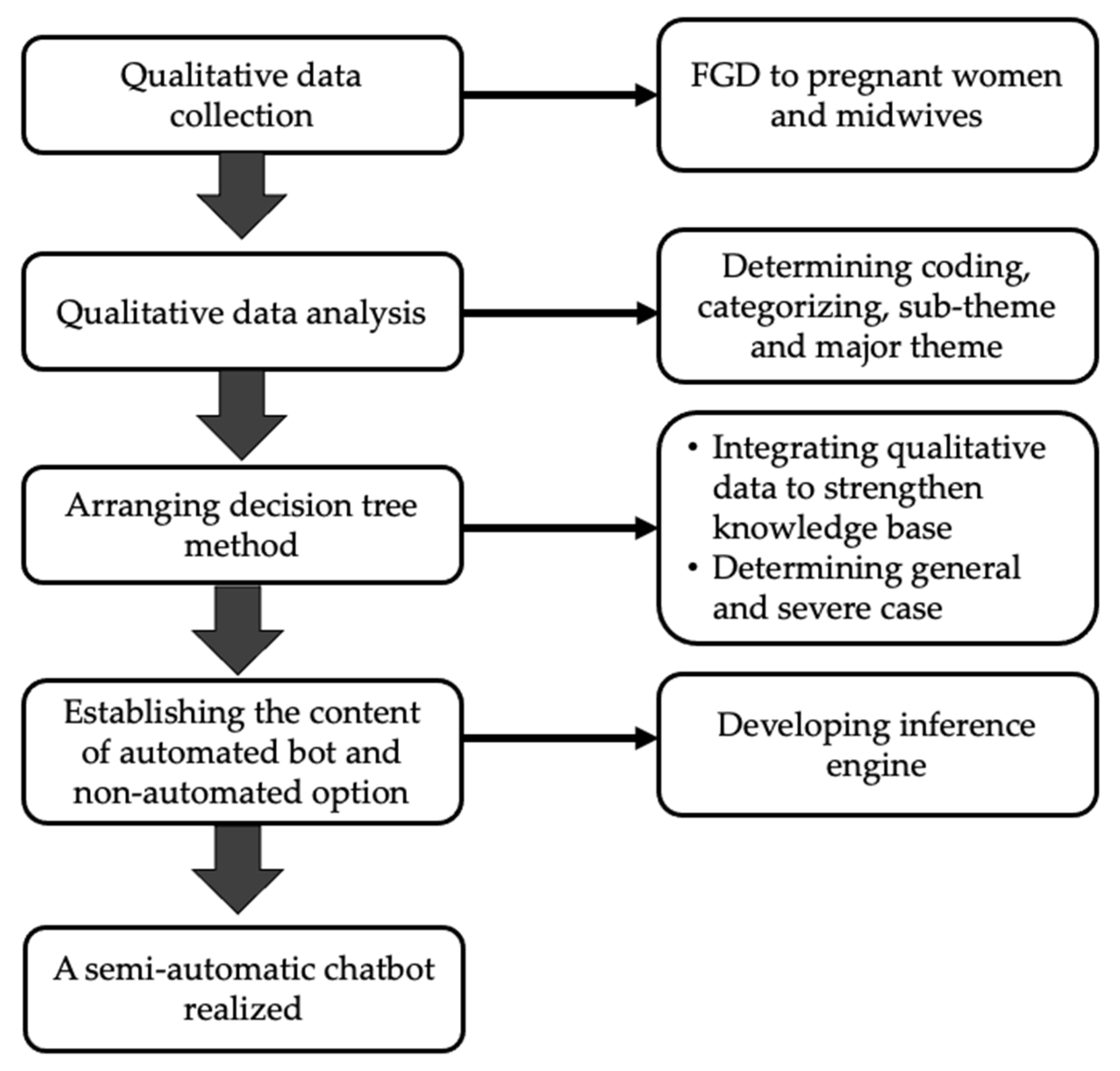

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participant Selection

2.3. Setting

2.4. Interview Guide

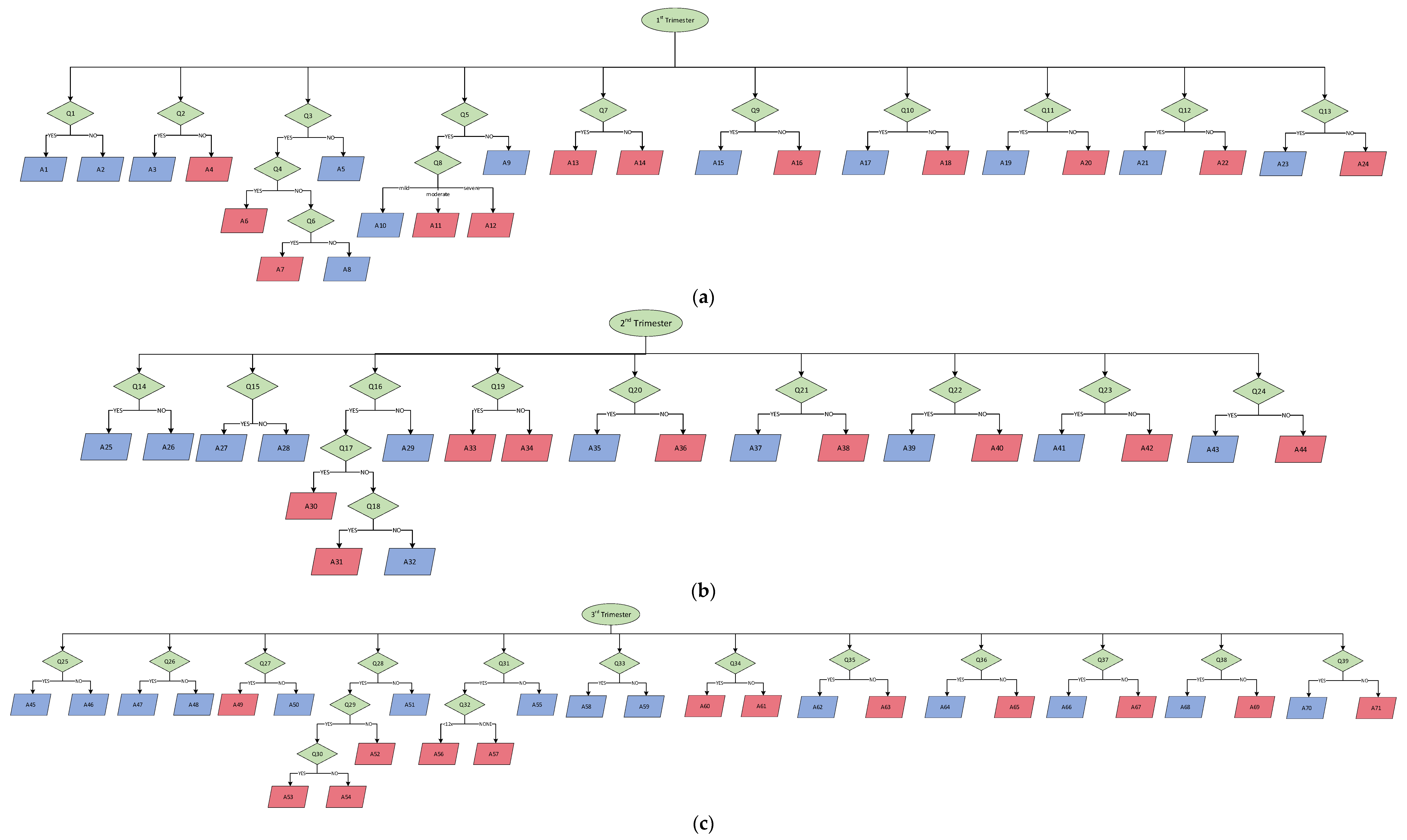

2.5. Data Analysis and Decision Tree Method

3. Results

3.1. Maternal Health Education

3.1.1. Physical Education

“…about complaints of nausea, vomiting and current condition … Yes, so we can consult quickly”(Pregnant Women’s FGD)

“General danger signs, nausea and vomiting, signs of bleeding or heartburn maybe yes, dizziness, stomach pains like that. How to drink iron tablet (Fe), vitamins, all shown.”(Midwives’ FGD)

“Many people complain of back pain, I said because the baby is getting bigger and want to give birth”(Midwives’ FGD)

3.1.2. Psychological Education

“Because we are also often given mental screening for pregnant women in the health care programs, such as filling questionnaires like do you feel, for example, that you have not slept for three days or not? I think it’s important to give mental education by chatbot”(Midwives’ FGD)

“Ee.. that’s not all. The mental preparation before giving birth needs to be supported and educated”(Pregnant Women’s FGD)

3.1.3. Lifestyle Change Education

“The way husband and wife may have sex in the first pregnancy. How many months or how many weeks is the inspection? Eating patterns, resting patterns, sleeping patterns”(Midwives FGD)

“Avoiding unhealthy foods.. Not staying up late, sleeping regularly”(Midwives’ FGD)

“Yes, how do you do it every day to stay healthy. Dietary habit. How do you keep it clean.”(Pregnant Women FGD)

“Clothes. Some pregnant women still wear little pants. The pants are strict jeans normally. Then sandals are usually high heels for pregnant women”(Midwives’ FGD)

3.2. Information on Maternal Health Service

3.2.1. Mother’s Health Checkup

“Schedule an appointment or consul meet with the midwife”(Pregnant women’s FGD)

“Pregnant women do not schedule repeat visits once a day, for example, once a month. Trimester from this to this. For those who are 8 months and over 2 weeks, once. So someone asked later to check again when yes. Later, if I control it again, I’m afraid I’ll forget again. But usually, if it’s like you’ve been to the health center, I’ll let you know the return visit”(Midwives’ FGD)

3.2.2. Mother’s Service Support

“Lab checks. Ultrasound, screening”(Midwives’ FGD)

“There are also deliveries (by parajis), so maybe the education is lacking, yes, the education is like that. Ee..yes, the economy is too. The average is the economy. There are still some, but not many. It’s just… there are. The second first child is the same as the paraji, huh”(Midwives’ FGD)

“Sometimes, people who are economically dependent are thinking about costs. At least we should be educated about BPJS (national health insurance) problems from the start”(Midwives’ FGD)

3.3. Health Monitoring

3.3.1. General Health Monitoring

“You can remind us that there are several programs, which are like a class for pregnant women, can you not include them so they can join. Even though we don’t…”(Pregnant Women’s FGD)

“For example, from the pregnant woman, there is this complaint. For example, all complaints are accommodated by the chatbot. Answered by chat, how is it? Later, they will ask again, if the chatbot has not been able to accommodate the patient’s answer, maybe they can be directed to the midwife as soon as possible”.(Midwives’ FGD)

3.3.2. Advanced Monitoring

“…about complaints… Yes, so we can consult with the person concerned, the health workers as well so that we know that we are not driven by google. So go straight to the experts…”(Pregnant Women’s FGD)

“Well, for example, in my opinion, everything should be accommodated first. If there are 10 patients, try to be answered by the chatbot first. Well, later, if the patient has been accommodated with the chatbot’s answer, thank God. If the patient still feels anxious and wants to ask further questions, it can be brought up to communicate with the midwife”(Midwives’ FGD)

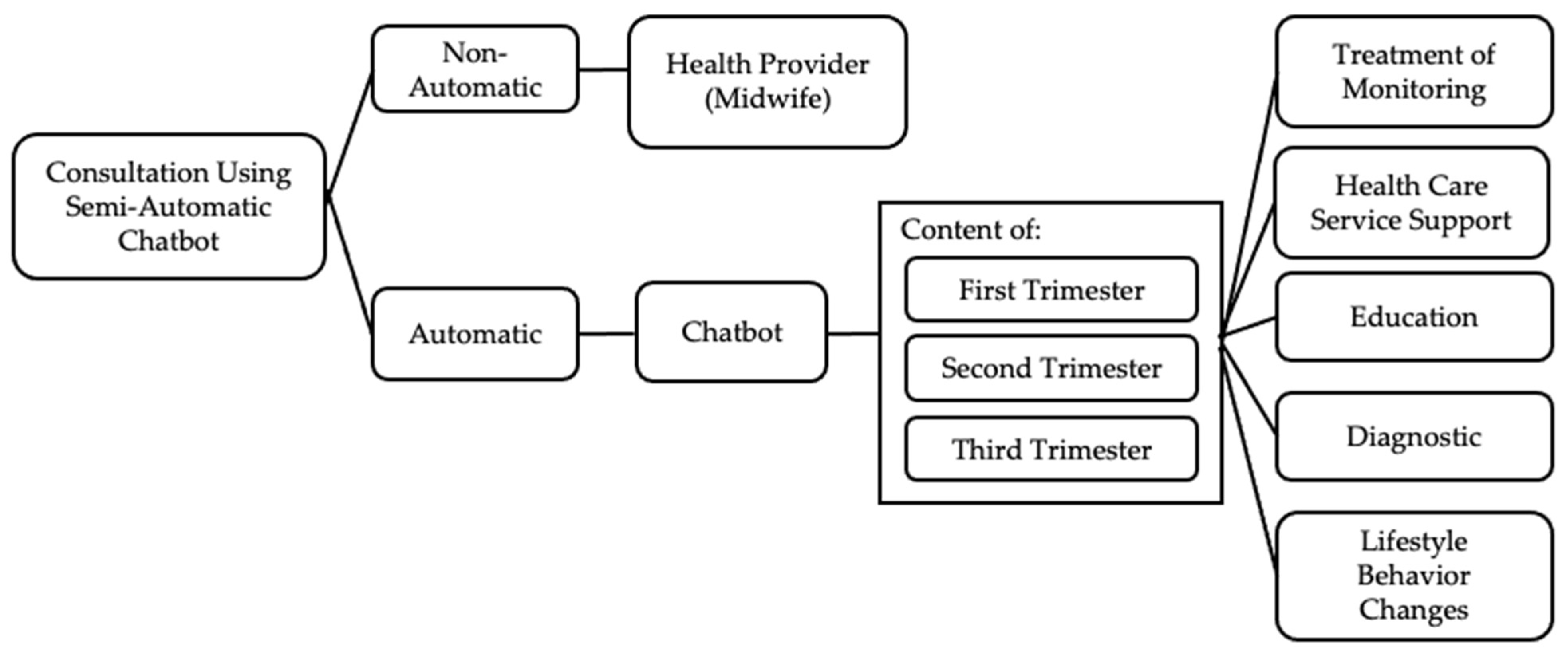

4. Development of the Chatbot

5. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No | Questions | Key Probing |

|---|---|---|

| A | Usage of Health Care Chatbots | |

| What do you think about using semi-automated chatbot-based teleconsultation in Posyandu services? | How familiar are people with the help of semi-automated chatbots | |

| B | Perceived benefits of healthcare chatbots | |

| What do you think about the benefits of using chatbots in healthcare for patients? | Treatment and monitoring Health care support Education Changes in lifestyle behavior Diagnosis | |

| C | Content and substance | |

| 1 | Treatment and Monitoring | |

| What information should the chatbot provide regarding treatment and health monitoring? | Pregnant women in all Trimesters Treatment: Iron Tablet, Folic Acid, calcium, nutrition General and severe complaint | |

| 2 | Health Care Services Support | |

| What information do you think the chatbot should provide regarding healthcare support? | Pregnant women in all Trimesters Place of delivery Supporting service Mental support | |

| 3 | Education | |

| In your opinion, what information should a chatbot provide regarding health education? | Pregnant women 1st Trimester (adaptation, discomfort, nutrition) Pregnant women 2nd Trimester (discomfort, complaints) Pregnant women 3rd Trimester (delivery plan, family planning) Prevention of eclampsia | |

| 4 | Lifestyle Behavioral Changes | |

| In your opinion, what information should be provided by chatbots regarding lifestyle and changes in health habits? | Nutrition Personal hygiene Exercise Daily habit | |

| 5 | Diagnosis tentative | |

| In your opinion, what information should be provided by chatbots and chat midwives regarding health diagnosis? | Pregnant women in all Trimesters Anemia Chronic energy deficiency Pre-eclampsia | |

Appendix B

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| Q1 | Do you know the signs of chronic energy deficiency (CED) in pregnant women? |

| Q2 | Do you regularly take iron tablets? |

| Q3 | Do you feel dizzy? |

| Q4 | Does high blood pressure accompany it? |

| Q5 | Do you have nausea and vomiting? |

| Q6 | If not, is it accompanied by other complaints? |

| Q7 | Is there any spot bleeding from the vagina? |

| Q8 | How many times have you had nausea in the last 24 h? |

| Q9 | Do you know about prenatal care or antenatal care (ANC)? |

| Q10 | Do you know the purpose of antenatal care? |

| Q11 | Do you know the type and purpose of a repeat pregnancy visit? |

| Q12 | Do you know about supporting examinations during pregnancy? |

| Q13 | Do you already know about the financing of pregnancy and childbirth examinations? |

| Q14 | Do you have back pain? |

| Q15 | Do you feel the urge to urinate frequently? (Frequency about 10 times per day?) |

| Q16 | Do you feel dizzy? |

| Q17 | Is there any spot bleeding from the vagina? |

| Q18 | Does high blood pressure accompany it? |

| Q19 | If not, is it accompanied by other complaints? |

| Q20 | Do you know of prenatal care or antenatal care (ANC)? |

| Q21 | Do you know the purpose of antenatal care? |

| Q22 | Do you know the type and purpose of a repeat pregnancy visit? |

| Q23 | Do you know about supporting examinations during pregnancy? |

| Q24 | Do you already know about the financing of pregnancy and childbirth examinations? |

| Q25 | Do you have back pain? |

| Q26 | Do you feel the urge to urinate frequently? (Frequency about 10 times per day?) |

| Q27 | Do you feel a regular contractions? |

| Q28 | Do you feel dizzy or have a headache? |

| Q29 | If so, is it accompanied by high blood pressure of more than 140/90? |

| Q30 | If so, is it accompanied by swelling in the feet, hands, and face, or impaired vision/blurred vision? |

| Q31 | Do you feel the fetal movement is reduced? |

| Q32 | If yes, how many times did you feel fetal movements? |

| Q33 | Do you feel frequent hand and foot cramps? |

| Q34 | Do you often have trouble sleeping or feeling anxious? |

| Q35 | Do you know about prenatal care or antenatal care (ANC)? |

| Q36 | Do you know the purpose of antenatal care? |

| Q37 | Do you know the type and purpose of a repeat pregnancy visit? |

| Q38 | Do you know about supporting examinations during pregnancy? |

| Q39 | Do you already know about the financing of pregnancy and childbirth examinations? |

Appendix C

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| A1 | Please comply with the principles of balanced nutrition, such as daily food composition containing nutrients according to the body’s needs, managing food diversity, physical activity, personal hygiene behavior, and maintaining body weight to prevent nutritional problems. |

| A2 | Chronic energy deficiency (CED) is a condition when pregnant women who have been malnourished for a long time (several months/years) and whose upper arm circumference is less than 23.5 cm. Pregnant women with CED will give birth to low birth weight (LBW). Based on the national research data (2013), this problem needs special attention as the prevalence of the risk of CED in pregnant women is 24.2%. |

| A3 | Go ahead and regularly check with the midwife. The required daily quantity of iron (Fe) in pregnant women is about 800 mg. This requirement consists of 300 mg needed for the fetus and 500 g to increase the mass of maternal hemoglobin. An excess of about 200 mg can be excreted through the intestines, skin, and urine. In the diets of pregnant women, every 100 calories can produce as much as 8–10 mg of Fe. Thus, the need for iron is still lacking in pregnant women, so they need additional intake in the form of Fe tablets. |

| A4 | It is recommended to take blood-added tablets during pregnancy. If you do not know your hemoglobin level, you should regularly undergo laboratory tests and check with the midwife/doctor. During the gestation period, through the estimated 288 days, pregnant women make about 100 mg of iron. Thus, the need for iron is still lacking in pregnant women, so they need additional intake in the form of Fe tablets. Please consult the midwife => Chat midwife. |

| A5 | Please continue to the other question. |

| A6 | If so, periodic checks need to be carried out by health workers. Dizziness with hypertension (high blood pressure) is due to reduced blood flow to the brain, so oxygen intake is reduced, causing dizziness. Besides food management, healthcare for mothers at home includes adequate rest and sleep, elevated legs, reducing strenuous and tiring activities, and deep breathing techniques can be alternative treatments for dizziness with hypertension (Hicks, 2015; Irianti et al., 2014). Please consult the midwife => and chat midwife. |

| A7 | If yes, please consult a midwife. Dizziness during pregnancy can be caused by anemia, hypertension, and low sugar levels. Anemia occurs due to increased blood plasma volume, which causes the mother’s hemoglobin level to decrease. Pregnant women with anemia should consume an additional iron tablet to increase hemoglobin levels or increase the intake of foods containing iron. Besides, pregnant women with low sugar levels can be supported with nutritionally balanced foods during pregnancy and a healthy lifestyle. Please consult the midwife => and chat midwife. |

| A8 | If not, please maintain a pattern of rest, nutrition and light exercise. Dizziness or feeling faint or light-headed are typical symptoms during pregnancy. This is more common in the first trimester, but the mother may experience it during pregnancy. Dizziness during pregnancy usually occurs due to the body trying to balance the increased blood circulation and the fetus’s growth. When entering the second trimester of pregnancy, the enlarged uterus can press on the blood vessels, causing headaches or dizziness. |

| A9 | Please continue to the other question. |

| A10 | Morning sickness is one of pregnancy’s earliest, most common, and most stressful symptoms. Nearly 50–90% of pregnant women experience nausea and vomiting in the first trimester. Nausea and vomiting are often overlooked because they are considered a consequence of early pregnancy, without regard to its severe impact on women. Most pregnant women who experience morning sickness will experience changes in the hormones progesterone and estrogen in the body, which cause morning sickness in the first trimester of pregnancy. Get plenty of rest to relieve stress and relieve fatigue. Consume foods that are high in protein, low in fat, and smooth in texture for easy swallowing and digestion. Eat food in small portions, but often. Avoid oily, spicy or strong-smelling foods that can trigger nausea. Drink more water to prevent dehydration, and consume drinks containing ginger to relieve nausea and warm the body. Use aromatherapy to reduce morning sicknesses, drinks containing ginger to ease nausea, warm the body and take pregnancy supplements to meet the need for vitamins and iron. |

| A11 | Please check with a health worker to get optimal treatment. Please consult the midwife => Chat midwife. |

| A12 | Please go to a health worker immediately to get optimal treatment. Please consult the midwife => Chat midwife. |

| A13 | If so, bleeding is one of the danger signs for pregnant women. Please consult a health worker. Please consult the midwife => and chat midwife. |

| A14 | Please consult the midwife => and chat midwife. |

| A15 | Please continue to the next question. |

| A16 | 1st Trimester: 1 visit at 0–13 weeks of gestation 2nd Trimester: 1 visit at 14–28 weeks of gestation 3rd Trimester: 2 trips at 28–36 weeks of pregnancy and 36–40 weeks. Every pregnant woman is advised to have a comprehensive and quality antenatal visit at least four times, i.e., once before the 4th month of pregnancy, then around the 6th month of pregnancy, and two times around the 8th and 9th month of pregnancy. The minimum standard for ANC examination consists of 10 steps: 1. Weighing each visit and record. 2. Measuring blood pressure, usually 110/80–below 140/90. 3. Determining the value of nutritional status by measuring the upper arm circumference (LILA). 4. Determining uterine fundal height (top of the uterus): monitor fetal development. 5. Giving TT (Tetanus Toxoid) immunization. 6. Determine fetal presentation and fetal heart rate (FHR). 7. Giving iron tablets. 8. Conducting laboratory tests (syphilis, Hepatitis B and HIV). 9. Providing case management. 10. Conducting interviews (counseling), including planning for delivery and post-delivery. If you still want to ask further, please get in touch with the midwife. |

| A17 | Please continue to the next question. |

| A18 | 1. To optimize the mental and physical health of pregnant women. 2. To detect the risk of complications in pregnancy and childbirth. 3. To motivate the mother’s desire for the postpartum period and exclusive breastfeeding. If you still want to ask further, please get in touch with the midwife. |

| A19 | Please continue to the next question. |

| A20 | 1. The first visit in the first trimester (16 weeks) was carried out to screen and treat anemia, plan for delivery and treat complications due to medication. 2. The second visit in the second trimester (<28 weeks) was conducted for complications due to medication and medication screening for preeclampsia, Gemelli, infections of the reproductive organs, and urinary tract. 3. The third visit in the third trimester (<36 weeks) and the fourth visit in the third trimester (> 36 weeks) were carried out to identify any abnormalities in the location and presentation, strengthen delivery plans, and recognize signs of labor. If you still want to ask further, please get in touch with the midwife. |

| A21 | Please continue to the next question. |

| A22 | Urine test 1. The urine test is essential to the 1st-trimester pregnancy check. It aims to detect a positive pregnancy and whether there are other diseases that the pregnant woman suffers from. Some of the things that become the benchmark for urine tests are: 1. The protein and sugar levels in pregnant women’s urine tend to be low. In addition, the urine of pregnant women also contains the hormone HCG (Human Chorionic Gonadotropin) at relatively high levels. 2. If the urine contains high levels of ketones and sugar, it means that the pregnant woman has gestational diabetes. 3. Proteins in pregnant women signify that the mother has pre-eclampsia or certain bacterial infections. Blood Test 1. Determination of blood type, whether the mother’s blood type is A, B, AB or O. 2. Determination of rhesus blood, whether rhesus positive or negative. This rhesus examination is essential and will later be matched with the baby’s rhesus. The sign is standard if the mother and baby have the same rhesus. However, suppose the mother’s rhesus is different from the baby’s. If the mother is rhesus positive and the baby is rhesus negative, the baby will suffer from blood disorders. 3. Checking hemoglobin. It is also important to detect whether the mother has anemia. Pregnant women have hemoglobin levels of about 10–16 g per liter in their blood. 4. Hepatitis B and C examination is conducted to determine whether there is a viral infection in the mother’s liver. A pregnant woman with hepatitis is at risk of passing the disease on to her fetus. 5. Examination for rubella, a measles disease in which the mother’s body develops a red rash. This disease is a risk for mothers at under five months of gestational age. Generally, the rubella virus is transmitted through sneezing, saliva and coughing by the sufferer. Ultrasound test (ultrasonography) An examination that doctors offer to pregnant women is an ultrasound test. Today’s technology is very sophisticated. This makes it possible to detect the fetus from an early age (first trimester). This ultrasound test has many uses, including: 1. Observing the structure of the fetus in the stomach. 2. Checking the normal condition of the uterus, placenta, and amniotic fluid. 3. Observing the growth of the fetus. 4. Estimating gestational age. 5. Detecting the presence or absence of abnormalities or physical defects in the fetus. Triple Elimination Check Laboratory personnel carries out a capillary blood examination to determine the results of HIV, syphilis and hepatitis tests. Reasons to have a triple elimination check 1. Stopping the growth of HIV, syphilis, and hepatitis B in the bod 2. Protecting sexual partner from the transmission of HIV, syphilis, and hepatitis B 3. Having children who are free from HIV, syphilis, and hepatitis B If you still want to ask further, please get in touch with the midwife => chat midwife |

| A23 | Please continue to the next question. |

| A24 | To receive Indonesian National Health Insurance (JKN), please register first. During pregnancy, management JKN can cover 3 services, divided into: - Trimester 1: carried out once at 1–12 weeks of pregnancy - Trimester 2: carried out once at 13–28 weeks of pregnancy - Trimester 3: carried two times at 29–40 weeks of pregnancy JKN can cover the cost of ultrasonography services when pregnant women are referred by a First Level Health Facility (FKTP). The cost of pregnancy checks borne by JKN: 1. Pre-delivery or antenatal care (ANC) examination - In the form of a package with a maximum of 4 visits, worth IDR 200,000. - ANC checks that are not only carried out in one place are worth IDR 50,000 per visit. 2. Normal delivery or vaginal delivery - Normal delivery performed by a midwife is worth IDR 700,000. - Normal delivery performed by a doctor is worth IDR 800,000. - Normal delivery with basic emergency measures at the Puskesmas is covered by Rp. 950,000. 3. Deliveries referred to advanced-level health facilities Under certain conditions, pregnant women participating in JKN who cannot give birth typically, and must be referred to help through a cesarean section due to limited experts and medical equipment, can be covered by JKN. If you still want to ask further, please get in touch with the midwife. |

| A25 | If so, this is normal in the 3rd trimester due to the enlargement of the uterus. Regular exercise is a critical component of lifestyle interventions recommended for pregnant women as part of antenatal care (ANC) to prevent excessive weight gain during pregnancy. Pregnant women with low back and pelvic pain usually improve within a few months after birth (WHO, 2016). |

| A26 | Please continue to the other question. |

| A27 | If so, this is normal for pregnant women in the 2nd trimester due to pressure on the bladder from the enlarged uterus. |

| A28 | Please continue to the other question. |

| A29 | Please continue to the other question. |

| A30 | If so, periodic checks need to be carried out by health workers. Dizziness with hypertension (high blood pressure) is due to reduced blood flow to the brain, so oxygen intake is reduced, causing dizziness. Besides food management, healthcare for mothers at home includes adequate rest and sleep, elevated legs, reduced strenuous and tiring activities, and deep breathing techniques can be alternative treatments for dizziness with hypertension (Hicks, 2015; Irianti et al., 2014). Please consult the midwife => and chat midwife. |

| A31 | If yes, please consult a midwife. Dizziness during pregnancy can be caused by anemia, hypertension, and low sugar levels. Anemia occurs due to increased blood plasma volume, which causes the mother’s hemoglobin level to decrease. Pregnant women with anemia should consume an additional iron tablet to increase hemoglobin levels or increase the intake of foods containing iron. Besides, pregnant women with low sugar levels can be supported with nutritionally balanced foods during pregnancy and a healthy lifestyle. Please consult the midwife => and chat midwife. |

| A32 | If not, please maintain a pattern of rest, nutrition, and light exercise. Dizziness or feeling faint or light-headed is typical symptoms during pregnancy. This is more common in the first trimester, but the mother may experience it during her pregnancy. Dizziness during pregnancy usually occurs due to the body trying to balance the increased blood circulation and the fetus’s growth. When entering the second trimester of pregnancy, the enlarged uterus can press on the blood vessels, causing headaches or dizziness. |

| A33 | If so, bleeding is one of the danger signs for pregnant women. Please consult a health worker. Please consult the midwife => and chat midwife. |

| A34 | Please consult the midwife => and chat midwife. |

| A35 | Please continue to the next question. |

| A36 | 1st trimester: 1 visit at 0–13 weeks of gestation 2nd trimester: 1 visit at 14–28 weeks of gestation 3rd trimester: 2 trips at 28–36 weeks of pregnancy and 36–40 weeks. Every pregnant woman is advised to have a comprehensive and quality antenatal visit at least four times, i.e., once before the 4th month of pregnancy, then around the 6th month of pregnancy, and two times around the 8th and 9th month of pregnancy. The minimum standard for ANC examination consists of 10 steps: 1. Weighing at each visit and recording. 2. Measuring blood pressure, usually 110/80–below 140/90. 3. Determining the value of nutritional status by measuring the upper arm circumference (LILA). 4. Determining uterine fundal height (top of the uterus): monitor fetal development. 5. Giving TT (Tetanus Toxoid) immunization. 6. Determine fetal presentation and fetal heart rate (FHR). 7. Giving iron tablets. 8. Conducting laboratory tests (syphilis, Hepatitis B and HIV). 9. Providing case management. 10. Conducting interviews (counseling), including planning for delivery and post-delivery. If you still want to ask further, please get in touch with the midwife. |

| A37 | Please continue to the next question. |

| A38 | 1. To optimize the mental and physical health of pregnant women. 2. To detect the risk of complications in pregnancy and childbirth 3. To motivate the mother’s desire for the postpartum period and exclusive breastfeeding. If you still want to ask further, please get in touch with the midwife |

| A39 | Please continue to the next question. |

| A40 | 1. The first visit in the 1st trimester (16 weeks) was carried out to screen and treat anemia, plan for delivery, and treat complications due to medication. 2. The second visit in the 2nd trimester (<28 weeks) was conducted for complications due to medication and medication screening for preeclampsia, Gemelli, infections of the reproductive organs, and urinary tract. 3. The third visit in the 3rd trimester (<36 weeks) and the fourth visit in the 3rd trimester (>36 weeks) were carried out to identify any abnormalities in the location and presentation, strengthen delivery plans, and recognize signs of labor. If you still want to ask further, please get in touch with the midwife. |

| A41 | Please continue to the next question. |

| A42 | Urine test 1. The urine test is essential to the 1st-trimester pregnancy check. It aims to detect a positive pregnancy and whether there are other diseases that the pregnant woman suffers from. Some of the things that become the benchmark for urine tests are: 1. The protein and sugar levels in pregnant women’s urine tend to be low. In addition, the urine of pregnant women also contains the hormone HCG (Human Chorionic Gonadotropin) at relatively high levels. 2. If the urine contains high levels of ketones and sugar, the pregnant woman has gestational diabetes. 3. Proteins in pregnant women signify that the mother has pre-eclampsia or certain bacterial infections. Blood Test 1. Determination of blood type, whether the mother’s blood type is A, B, AB, or O. 2. Determination of rhesus blood, whether rhesus positive or negative. This rhesus examination is essential, which will later be matched with the baby’s rhesus. The sign is standard if the mother and baby have the same rhesus. However, suppose the mother has a different rhesus from the baby. In that case, if the mother is rhesus positive and the baby is rhesus negative, the baby suffers from blood disorders. 3. Checking of hemoglobin. It is also important to detect whether the mother has anemia. Pregnant women have hemoglobin levels of about 10–16 g per liter in their blood. 4. Hepatitis B and C examination is to determine whether there is a viral infection in the mother’s liver or not. A pregnant woman with hepatitis is at risk of passing the disease on to her fetus. 5. Examination for rubella, a measles disease in which the mother’s body develops a red rash. This disease is a risk for mothers under five months of gestational age. Generally, the rubella virus is transmitted through the sneezing, saliva, and coughing of the sufferer. Ultrasound test (ultrasonography) An examination that doctors offer to pregnant women is an ultrasound test. Today’s technology is very sophisticated. This makes it possible to detect the fetus from an early age (first trimester). This ultrasound test has many uses, including: 1. Observing the structure of the fetus in the stomach 2. Checking the normal condition of the uterus, placenta, and amniotic fluid 3. Observing the growth of the fetus 4. Estimating gestational age 5. Detecting the presence or absence of abnormalities or physical defects in the fetus Triple Elimination Check Laboratory personnel carries out a capillary blood examination to determine the results of HIV, syphilis, and hepatitis tests. Reasons to undergo a triple elimination check: 1. Stopping the growth of HIV, syphilis, and hepatitis B in the bod 2. Protecting sexual partner from the transmission of HIV, syphilis, and hepatitis B 3. Having children who are free from HIV, syphilis, and hepatitis B If you still want to ask further, please get in touch with the midwife. |

| A43 | Please continue to the next question. |

| A44 | To receive Indonesian National Health Insurance (JKN), please register first. During pregnancy, management JKN can cover 3 services, divided into: - Trimester 1: carried out once at 1–12 weeks of pregnancy - Trimester 2: carried out once at 13–28 weeks of pregnancy - Trimester 3: carried two times at 29–40 weeks of pregnancy JKN can cover the cost of ultrasonography services when pregnant women are referred by a First Level Health Facility (FKTP). The cost of pregnancy checks borne by JKN: 1. Pre-delivery or antenatal care (ANC) examination - In the form of a package with a maximum of 4 visits worth IDR 200,000. - ANC checks that are not only carried out in one place are worth IDR 50,000 per visit. 2. Normal delivery or vaginal delivery - Normal delivery performed by a midwife, worth IDR 700,000. - Normal delivery performed by a doctor, worth IDR 800,000. - Normal delivery with basic emergency measures at the Puskesmas is covered by Rp. 950,000. 3. Deliveries referred to advanced-level health facilities Under certain conditions, pregnant women participating in JKN who cannot give birth typically, and must be referred to help through a cesarean section due to limited experts and medical equipment, can be covered by JKN. If you still want to ask further, please get in touch with the midwife. |

| A45 | If so, this is normal in the 3rd trimester due to the enlargement of the uterus. Regular exercise is a critical component of lifestyle interventions recommended for pregnant women as part of the ANC to prevent excessive weight gain during pregnancy. Regular exercise is an essential component of lifestyle interventions recommended for pregnant women as part of the ANC to avoid excessive weight gain during pregnancy. Pregnant women with low back and pelvic pain usually improve within a few months after birth (WHO, 2016). |

| A46 | Please continue to the other question. |

| A47 | If so, this is normal in the 3rd trimester of pregnant women due to pressure on the bladder from the enlargement of the uterus. |

| A48 | Please continue to the other question. |

| A49 | If so, these are signs of labor. Immediately prepare for the delivery process and go to the intended delivery service: => and chat midwife. |

| A50 | Please continue to other questions. |

| A51 | If not, please take a break and if the complaint continues, contact the midwife. Dizziness in pregnancy is a complaint that often occurs because changes in pregnancy hormones make blood vessels dilate. Dizziness in pregnancy is expected, but it is advisable to remain vigilant if dizziness is accompanied by other symptoms, such as blurred vision, abdominal pain, difficulty speaking, chest pain, tingling, rapid pulse, or vaginal bleeding. |

| A52 | If not, please take a break and if the complaint continues, contact the midwife. |

| A53 | If so, this is a sign of immediate danger to health workers. Chat to a midwife. |

| A54 | If not, please take a break and if the complaint continues, contact the midwife. |

| A55 | Please continue to the other question. |

| A56 | This is a sign of danger. Seek medical attention immediately. The reduced movement of the baby is one thing that needs to be watched out for directly by the health workers. => Chat Midwife. |

| A57 | This is a sign of danger. Seek medical attention immediately. Chat to a midwife. |

| A58 | Leg cramps usually occur twice a week or less frequently, usually at night, last a few seconds to a few minutes, and mostly go away on their own. Leg cramps occur in about 50% of pregnant women and subside after delivery. The mechanism of cramping is unknown and may be idiopathic. However, it could be due to physiological changes in neuromuscular performance, weight gain, joint weakness in the later stages of pregnancy, the insufficient blood supply to lower body organs, and increased pressure on the leg muscles during pregnancy. Pressure on the blood vessels and nerves due to an enlarged uterus, an imbalance between the intake and output of electrolytes and vitamins, and insufficient information on minerals may be other reasons for cramps (Mandouri, 2017). |

| A59 | Please continue to other questions. |

| A60 | If yes, this reflects an awareness that the pregnancy is nearing the end, so there is a fear of an abnormal delivery process, anxiety about whether the baby can be delivered safely, and worry if the baby is born in an abnormal condition. Do exercise, mindfulness, and relaxation (prenatal yoga). Physiological relaxation exercises will cause a relaxing effect that involves the parasympathetic nerves in the central nervous system, where one of the functions of the parasympathetic nerves is to reduce the production of the hormone adrenaline or epinephrine (stress hormone) and increase the secretion of the hormone noradrenaline or norepinephrine (relaxing hormone) so that there is a decrease in anxiety and tension in pregnant women, which causes them to become more relaxed and calmer (Davenport, 2007) => chat to a midwife. |

| A61 | Please consult the midwife => and chat midwife. |

| A62 | Please continue to the next question. |

| A63 | 1st trimester: 1 visit at 0–13 weeks of gestation 2nd trimester: 1 visit at 14–28 weeks of gestation 3rd trimester: 2 trips at 28–36 weeks of pregnancy and 36–40 weeks. Every pregnant woman is advised to have a comprehensive and quality antenatal visit at least four times, i.e., once before the 4th month of pregnancy, then around the 6th month of pregnancy, and two times around the 8th and 9th month of pregnancy. The minimum standard for ANC examination consists of 10 steps: 1. Weighing at each visit and recording. 2. Measuring blood pressure, usually 110/80–below 140/90. 3. Determining the value of nutritional status by measuring the upper arm circumference (LILA). 4. Determining uterine fundal height (top of the uterus): monitoring fetal development. 5. Giving TT (Tetanus Toxoid) immunization. 6. Determining fetal presentation and fetal heart rate (FHR). 7. Giving iron tablets 8. Conducting laboratory tests (syphilis, Hepatitis B and HIV). 9. Providing case management. 10. Conducting interviews (counseling), including planning for delivery and post-delivery. If you still want to ask further, please get in touch with the midwife. |

| A64 | Please continue to the next question. |

| A65 | 1. To optimize the mental and physical health of pregnant women. 2. To detect the risk of complications in pregnancy and childbirth 3. To motivate the mother’s desire for the postpartum period and exclusive breastfeeding. If you still want to ask further, please get in touch with the midwife. |

| A66 | Please continue to the next question. |

| A67 | 1. The first visit in the 1st trimester (16 weeks) was carried out to screen and treat anemia, plan for delivery, and treat complications due to medication. 2. Visit second in the 2nd trimester (<28 weeks) was conducted for complications due to medication and medication screening for preeclampsia, Gemelli, infections of the reproductive organs, and urinary tract. 3. The third visit in the 3rd trimester (<36 weeks) and the fourth visit in the 3rd trimester (>36 weeks) were carried out to identify any abnormalities in the location and presentation, strengthen delivery plans, and recognize signs of labor. If you still want to ask further, please get in touch with the midwife. |

| A68 | Please continue to the next question. |

| A69 | Urine test 1. The urine test is essential to the 1st-trimester pregnancy check. It aims to detect a positive pregnancy and whether there are other diseases that the pregnant woman suffers from. Some of the things that have become the benchmark for urine tests are: 1. The protein and sugar levels in pregnant women’s urine tend to be low. In addition, the urine of pregnant women also contains the hormone HCG (Human Chorionic Gonadotropin) at relatively high levels. 2. If the urine contains high levels of ketones and sugar, the pregnant woman has gestational diabetes. 3. Proteins in pregnant women signify that the mother has pre-eclampsia or certain bacterial infections. Blood Test 1. Determination of blood type, whether the mother’s blood type is A, B, AB, or O. 2. Determination of rhesus blood, whether rhesus positive or negative. This rhesus examination is essential and will later be matched with the baby’s rhesus. The sign is standard if the mother and baby have the same rhesus. However, suppose the mother’s rhesus is different from the baby’s. If the mother is rhesus positive and the baby is rhesus negative, the baby will suffer from blood disorders. 3. Check hemoglobin. It is also important to detect whether the mother has anemia. Pregnant women have hemoglobin levels of about 10–16 g per liter in their blood. 4. Hepatitis B and C examination is to determine whether there is a viral infection in the mother’s liver or not. A pregnant woman with hepatitis is at risk of passing the disease on to her fetus. 5. Examination for rubella, a measles disease in which the mother’s body develops a red rash. This disease is a risk for mothers under five months of gestational age. Generally, the rubella virus is transmitted through sneezing, saliva, and coughing by the sufferer. Ultrasound test (ultrasonography) An examination that doctors offer to pregnant women is an ultrasound test. Moreover, today’s technology is very sophisticated. This makes it possible to detect the fetus from an early age (first trimester). This ultrasound test has many uses, including: 1. Observing the structure of the fetus in the stomach 2. Checking the normal condition of the uterus, placenta, and amniotic fluid 3. Observing the growth of the fetus 4. Estimating gestational age 5. Detecting the presence or absence of abnormalities or physical defects in the fetus Triple Elimination Check Laboratory personnel carries out a capillary blood examination to determine the results of HIV, syphilis, and hepatitis tests. Reasons to do a triple elimination check: 1. Stopping the growth of HIV, syphilis, and hepatitis B in the bod 2. Protecting sexual partner from the transmission of HIV, syphilis, and hepatitis B 3. Having children who are free from HIV, syphilis, and hepatitis B If you still want to ask further, don’t hesitate to get in touch with the midwife. |

| A70 | Please continue to the next question. |

| A71 | To receive Indonesian National Health Insurance (JKN), please register first. During pregnancy, management JKN can cover 3 services, divided into: - Trimester 1: carried out once at 1–12 weeks of pregnancy - Trimester 2: carried out once at 13–28 weeks of pregnancy - Trimester 3: carried two times at 29–40 weeks of pregnancy JKN can cover the cost of ultrasonography services when pregnant women are referred by a First Level Health Facility (FKTP. The cost of pregnancy checks borne by JKN: 1. Pre-delivery or antenatal care (ANC) examination - In the form of a package with a maximum of 4 visits, worth IDR 200,000. - ANC checks that are not only carried out in one place are worth IDR 50,000 per visit. 2. Normal delivery or vaginal delivery - Normal delivery performed by a midwife, worth IDR 700,000. - Normal delivery performed by a doctor, worth IDR 800,000. - Normal delivery with basic emergency measures at the puskesmas is covered by Rp. 950,000. 3. Deliveries referred to advanced-level health facilities Under certain conditions, pregnant women participating in JKN who cannot give birth typically, and must be referred to help through a cesarean section due to limited experts and medical equipment, can be covered by JKN. If you still want to ask further, please get in touch with the midwife. |

References

- Mosa, M.; Yoo, I.; Sheets, L. A systematic review of healthcare applications for smartphones. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2012, 12, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernsting, C.; Dombrowski, S.U.; Oedekoven, M.; O’Sullivan, J.L.; Kanzler, E.; Kuhlmey, A.; Gellert, P. Using smartphones and health apps to change and manage health behaviors: A population-based survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. mHealth: New horizons for health through mobile technologies. Observatory 2011, 3, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyawa, G.E.; Hamunyela, S. MHealth Apps and Services for Maternal Healthcare in Developing Countries. In Proceedings of the 2019 IST-Africa Week Conference, IST-Africa 2019, Nairobi, Kenya, 8–10 May 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BPS-Statistics Indonesia. Telecommunication Statistics In Indonesia 2020. BPS-Statistics Indonesia. 2020. Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/publication/2021/10/11/e03aca1e6ae93396ee660328/statistik-telekomunikasi-indonesia-2020.html (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Zhang, P.; Dong, L.; Chen, H.; Chai, Y.; Liu, J. The rise and need for mobile apps for maternal and child health care in China: Survey based on app markets. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e9302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusyanti, T.; Wirakusumah, F.F.; Rinawan, F.R.; Muhith, A. Technology-Based (Mhealth) and Standard/Traditional Maternal Care for Pregnant Woman: A Systematic Literature Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, S.S.L.; Goonawardene, N. Internet health information seeking and the patient-physician relationship: A systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e5729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Ministry of Republic Indonesia. Indonesia Health Profil 2020. 2021. Available online: https://www.kemkes.go.id/folder/view/01/structure-publikasi-pusdatin-profil-kesehatan.html (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Jokowi. Presidential Decree No. 18 Year of 2020. National Mid-Term Development Plan 2015–2019. 2020, pp. 1–300. Available online: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Home/Details/131386/perpres-no-18-tahun-2020 (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Soedirham, O. Integrated Services Post (Posyandu) as Sociocultural Approach for Primary Health Care Issue. Kesmas Natl. Public Health J. 2012, 7, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinawan, F.R.; Susanti, A.I.; Amelia, I.; Ardisasmita, M.N.; Dewi, R.K.; Ferdian, D.; Purnama, W.S.; Purbasari, A. Understanding mobile application development and implementation for monitoring Posyandu data in Indonesia: A 3-year hybrid action study to build “ a bridge ” from the community to the national scale. BMJ Public Health 2021, 21, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinawan, F.R.; Faza, A.; Susanti, A.I.; Purnama, W.G.; Indraswari, N.; Ferdian, D.; Fatimah, S.N.; Purbasari, A.; Zulianto, A.; Sari, A.N.; et al. Posyandu Application for Monitoring Children Under-Five: A 3-Year Data Quality Map in Indonesia. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellata, A.G.; Rinawan, F.R.; Nyarumenteng, G.; Winarno, A.; Susanti, A.I.; Purnama, W.G. Exploration of Telemidwifery: An Initiation of Application Menu in Indonesia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudier, P.; Kondrateva, G.; Ammi, C.; Chang, V.; Schiavone, F. Patients’ perceptions of teleconsultation during COVID-19: A cross-national study. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 163, 120510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palanica, A.; Flaschner, P.; Thommandram, A.; Li, M.; Fossat, Y. Physicians’ perceptions of chatbots in health care: Cross-sectional web-based survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e12887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamopoulou, E.; Moussiades, L. An Overview of Chatbot Technology. In IFIP International Conference on Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Car, L.T.; Dhinagaran, D.A.; Kyaw, B.M.; Kowatsch, T.; Joty, S.; Theng, Y.L.; Atun, R. Conversational Agents in Health Care: Scoping Review and Conceptual Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e17158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Alrazaq, A.A.; Rababeh, A.; Alajlani, M.; Bewick, B.M.; Househ, M. Effectiveness and safety of using chatbots to improve mental health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e16021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.J.; Zhang, J.; Fang, M.L.; Fukuoka, Y. A systematic review of artificial intelligence chatbots for promoting physical activity, healthy diet, and weight loss. International. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachner, T.; Keller, R.; Wangenheim, F. Artificial intelligence-based conversational agents for chronic conditions: Systematic literature review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e20701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonkwo, C.W.; Ade-Ibijola, A. Chatbots applications in education: A systematic review. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2021, 2, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Chao, D.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Tian, F. Utilization of self-diagnosis health chatbots in real-world settings: Case study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaaeldin, R.; Asfoura, E.; Abdel-Haq, M.S. Developing Chatbot System To Support Decision Making Based on Big Data Analytics. J. Manag. Inf. Decis. Sci. 2021, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, K.; Cho, H.Y.; Park, J.Y. A chatbot for perinatal women’s and partner’s obstetric and mental health care: Development and usability evaluation study. JMIR Med. Inform. 2021, 9, e18607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farao, J.; Malila, B.; Conrad, N.; Mutsvangwa, T.; Rangaka, M.X.; Douglas, T.S. A user-centred design framework for mHealth. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Gómez, E.; Martín-Salvador, A.; Luque-Vara, T.; Sánchez-Ojeda, M.A.; Navarro-Prado, S.; Enrique-Mirón, C. Content validation through expert judgment of an instrument on the nutritional knowledge, beliefs, and habits of pregnant women. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brnabic, A.; Hess, L.M. Systematic literature review of machine learning methods used in the analysis of real-world data for patient-provider decision making. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2021, 21, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podgorelec, V.; Kokol, P.; Stiglic, B.; Rozman, I. Decision Trees: An Overview and Their Use in Medicine. J. Med. Syst. 2002, 103, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wu, T.T.; Yang, D.L.; Guo, Y.S.; Liu, P.C.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, L.P. Decision tree model for predicting in-hospital cardiac arrest among patients admitted with acute coronary syndrome. Clin. Cardiol. 2019, 42, 1087–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.Y.; Lu, Y. Decision tree methods: Applications for classification and prediction. Shanghai Arch. Psychiatry 2015, 27, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; He, Z.; Yi, Z.; Yuan, C.; Suo, W.; Pei, S.; Li, Y.; Ma, H.; Wang, H.; Xu, B.; et al. Application of a decision tree model in the early identification of severe patients with severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chern, C.C.; Chen, Y.J.; Hsiao, B. Decision tree-based classifier in providing telehealth service. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2019, 19, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.; Yeh, J.H.; Chiu, H.C.; Chen, Y.M.; Jhou, M.J.; Liu, T.C.; Lu, C.J. Utilization of Decision Tree Algorithms for Supporting the Prediction of Intensive Care Unit Admission of Myasthenia Gravis: A Machine Learning-Based Approach. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.-M. Clinical Decision Analysis using Decision Tree. Epidemiol. Health 2014, 36, e2014025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.H.; Prajapati, P. Study and Analysis of Decision Tree Based Classification Algorithms. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2018, 6, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhirud, N.; Tataale, S.; Randive, S.; Nahar, S. A Literature Review On Chatbots In Healthcare Domain. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2019, 8, 225–231. [Google Scholar]

- Park, E.Y.; Yi, M.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, H. A decision tree model for breast reconstruction of women with breast cancer: A mixed method approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddique, S.; Chow, J.C.L. Machine Learning in Healthcare Communication. Encyclopedia 2021, 1, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parviainen, J.; Rantala, J. Chatbot breakthrough in the 2020s ? An ethical reflection on the trend of automated consultations in health care. Med. Health Care Philos. 2021, 25, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadarzynski, T.; Miles, O.; Cowie, A.; Ridge, D. Acceptability of artificial intelligence (AI)-led chatbot services in healthcare: A mixed-methods study. Digit. Health 2019, 5, 2055207619871808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, O.; West, R.; Nadarzynski, T. Health chatbots acceptability moderated by perceived stigma and severity: A cross-sectional survey. Digit. Health 2021, 7, 20552076211063012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, M.; Baez, M.; Casati, F. Chatbots as Conversational Healthcare Services. IEEE Internet Comput. 2021, 25, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjo, L.; Dunn, A.G.; Tong, H.L.; Kocaballi, A.B.; Chen, J.; Bashir, R.; Surian, D.; Gallego, B.; Magrabi, F.; Lau, A.Y.S.; et al. Conversational agents in healthcare: A systematic review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2018, 25, 1248–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.; Korstjens, I. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 24, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyumba, T.O.; Wilson, K.; Derrick, C.J.; Mukherjee, N. The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2018, 9, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, F.G. Williams Obstetrics, 25th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kiger, M.E.; Varpio, L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med. Teach. 2020, 42, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Haji Ali Afzali, H.; Karnon, J. Specification and Implementation of Decision Analytic Model Structures for Economic Evaluation of Health Care Technologies. In Encyclopedia of Health Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.; Burford, O.; Emmerton, L. Mobile health apps to facilitate self-care: A qualitative study of user experiences. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binyamin, S.S. Proposing a mobile apps acceptance model for users in the health area : A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Health Inform. J. 2021, 27, 1460458220976737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luca, E.J.; Ulyannikova, Y. Towards a User-Centred Systematic Review Service: The Transformative Power of Service Design Thinking. J. Aust. Libr. Inf. Assoc. 2020, 69, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, M.; Stevens, B.; Rao, M.; Riahi, S.; Lanese, A.; Li, S. Usability, acceptability, and feasibility of the Implementation of Infant Pain Practice Change (ImPaC) Resource. Paediatr. Neonatal Pain 2020, 2, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudah, A.A.; Al-Emran, M. applied sciences Technology Acceptance in Healthcare: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais, S.; Petrova, K.; Parry, D. Enhancing system acceptance through user-centred design: Integrating patient generated wellness data. Sensors 2022, 22, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Singh, S.; Chandan, J.S.; Robbins, T.; Patel, V. Qualitative exploration of digital chatbot use in medical education: A pilot study. Digit. Health 2021, 7, 20552076211038151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefyev, A.; Lechauve, J.-B.; Gay, C.; Gerbaud, L.; Chérillat, M.S.; Figueiredo, I.T.; Plan-Paquet, A.; Coudeyre, E. Mobile application development through qualitative research in education program for chronic low back patients. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2017, 60, e102–e103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowatsch, T.; Otto, L.; Harperink, S.; Cotti, A.; Schlieter, H. A design and evaluation framework for digital health interventions. IT-Inf. Technol. 2019, 61, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Bao, J.; Setiawan, I.M.A.; Saptono, A.; Parmanto, B. The mhealth app usability questionnaire (MAUQ): Development and validation study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e11500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokmin, N.A.M.; Ibrahim, N.A. The evaluation of chatbot as a tool for health literacy education among undergraduate students. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 6033–6049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, E.; Truong, M.B.T.; Nordeng, H. Use of decision support tools to empower pregnant women: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoi, T.J.; Kibusi, S.M. Improving pregnant women’s knowledge on danger signs and birth preparedness practices using an interactive mobile messaging alert system in Dodoma region, Tanzania: A controlled quasi experimental study. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.L.; Falah-Hassani, K.; Shiri, R. Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2017, 210, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J. Using Health Chatbots for Behavior Change : A Mapping Study. J. Med. Syst. 2019, 43, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, E.M.; Harake, N.R.; Ward, H.E.; Stoeckl, S.E.; Vargas, J.; Minkel, J.; Parks, A.C.; Zilca, R. Artificially intelligent chatbots in digital mental health interventions: A review. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2021, 18, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidyam, A.N.; Wisniewski, H.; Halamka, J.D.; Kashavan, M.S.; Torous, J.B. Chatbots and Conversational Agents in Mental Health: A Review of the Psychiatric Landscape. Can. J. Psychiatry 2019, 64, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Suh, C.; Choi, S.P.; Choi, M.; Kim, D.H.; Son, B.C. Development of a Chatbot Program for Follow-Up Management of Workers’ General Health Examinations in Korea : A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Peng, H.; Song, X.; Xu, C.; Zhang, M. Using AI chatbots to provide self-help depression interventions for university students: A randomized trial of effectiveness. Internet Interv. 2022, 27, 100495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kretzschmar, K.; Tyroll, H.; Pavarini, G. Can Your Phone Be Your Therapist ? Young People ’ s Ethical Perspectives on the Use of Fully Automated Conversational Agents (Chatbots) in Mental Health Support. Biomed. Inform. Insights 2019, 11, 1178222619829083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.; Le, J.H.; Vittinghoff, E.; Fukuoka, Y. mHealth Physical Activity Intervention: A Randomized Pilot Study in Physically Inactive Pregnant Women. Matern. Child Health J. 2016, 20, 1091–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, T.; Strömmer, S.; Vogel, C.; Harvey, N.C.; Cooper, C.; Inskip, H.; Woods-Townsend, K.; Baird, J.; Barker, M.; Lawrence, W.; et al. Improving pregnant women’s diet and physical activity behaviours: The emergent role of health identity. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avila-Tomas, J.F.; Olano-Espinosa, E.; Minué-Lorenzo, C.; Martinez-Suberbiola, F.J.; Matilla-Pardo, B.; Serrano-Serrano, M.E.; Escortell-Mayor, E.; the Group Dej@lo. Effectiveness of a chat-bot for the adult population to quit smoking: Protocol of a pragmatic clinical trial in primary care (Dejal@). BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2019, 19, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Oh, Y.J.; Lange, P.; Yu, Z.; Fukuoka, Y. Artificial intelligence chatbot behavior change model for designing artificial intelligence chatbots to promote physical activity and a healthy diet: Viewpoint. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e22845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Decary, M. Artificial intelligence in healthcare : An essential guide for health leaders. Healthc. Manag. Forum. 2020, 33, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, A.; Greene, C.C.; Greene, C. Artificial intelligence, chatbots, and the future of medicine. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 481–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhu, B.; Yuan, C.; Zhao, C.; Wang, J.; Ruan, Q.; Han, C.; Bao, Z.; Chen, J.; Arceneaux, K.; et al. A parsimonious approach for screening moderate-to-profound hearing loss in a community-dwelling geriatric population based on a decision tree analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Miao, M. Application of Decision Tree Intelligent Algorithm in Data Analysis of Physical Health Test. J. Healthc. Eng. 2022, 2022, 8584377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokach, L.; Maimon, O. Data Mining With Decision Trees. In Proactive Data Mining with Decision Trees; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ajlan, A. The Comparison between Forward and Backward Chaining. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Comput. 2015, 5, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prambudi, D.A.; Widodo, C.E.; Widodo, A.P. Expert System Application of Forward Chaining and Certainty Factors Method for the Decision of Contraception Tools. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2018; Volume 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Age | Trimester | Parity | Occupation | Educational Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RI1 | 22 | 3 | Multiparous | Housewife | Junior High School |

| RI2 | 27 | 3 | Primiparous | Housewife | Senior High School |

| RI3 | 24 | 3 | Primiparous | Housewife | Senior High School |

| RI4 | 23 | 2 | Primiparous | Housewife | Senior High School |

| RI5 | 33 | 1 | Multiparous | Housewife | Junior High School |

| RI6 | 30 | 3 | Multiparous | Housewife | Elementary School |

| RI7 | 28 | 1 | Multiparous | Housewife | Senior High School |

| RI8 | 27 | 2 | Multiparous | Housewife | Senior High School |

| RI9 | 24 | 1 | Primiparous | Housewife | Senior High School |

| RI10 | 30 | 2 | Multiparous | Housewife | Senior High School |

| Code | Age | Midwifery Education | Participated in iPosyandu Training |

|---|---|---|---|

| RB1 | 32 | Bachelor Degree | Had attended training |

| RB2 | 31 | Diploma Degree | Had attended training |

| RB3 | 33 | Diploma Degree | Had attended training |

| RB4 | 34 | Diploma Degree | Had attended training |

| RB5 | 32 | Diploma Degree | Had attended training |

| RB6 | 36 | Diploma Degree | Had attended training |

| RB7 | 36 | Diploma Degree | Had attended training |

| RB8 | 32 | Bachelor Degree | Had attended training |

| RB9 | 32 | Diploma Degree | Had attended training |

| RB10 | 33 | Diploma Degree | Had attended training |

| RB11 | 34 | Diploma Degree | Had attended training |

| RB12 | 35 | Diploma Degree | Had attended training |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Puspitasari, I.W.; Rinawan, F.R.; Purnama, W.G.; Susiarno, H.; Susanti, A.I. Development of a Chatbot for Pregnant Women on a Posyandu Application in Indonesia: From Qualitative Approach to Decision Tree Method. Informatics 2022, 9, 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics9040088

Puspitasari IW, Rinawan FR, Purnama WG, Susiarno H, Susanti AI. Development of a Chatbot for Pregnant Women on a Posyandu Application in Indonesia: From Qualitative Approach to Decision Tree Method. Informatics. 2022; 9(4):88. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics9040088

Chicago/Turabian StylePuspitasari, Indriana Widya, Fedri Ruluwedrata Rinawan, Wanda Gusdya Purnama, Hadi Susiarno, and Ari Indra Susanti. 2022. "Development of a Chatbot for Pregnant Women on a Posyandu Application in Indonesia: From Qualitative Approach to Decision Tree Method" Informatics 9, no. 4: 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics9040088

APA StylePuspitasari, I. W., Rinawan, F. R., Purnama, W. G., Susiarno, H., & Susanti, A. I. (2022). Development of a Chatbot for Pregnant Women on a Posyandu Application in Indonesia: From Qualitative Approach to Decision Tree Method. Informatics, 9(4), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics9040088