Strengthening Early Childhood Protective Factors Through Safe and Supportive Classrooms: Findings from Jump Start + COVID Support

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Was the teacher’s implementation of JS+CS practices effective in increasing children’s protective factors over time, as mediated by teacher stress, teacher self-efficacy, and classroom practices, relative to the active control?

- Was the teacher’s implementation of JS+CS practices effective in decreasing children’s problematic behaviors over time, as mediated by teacher stress, teacher self-efficacy, and classroom practices, relative to the active control?

- To what extent do child externalizing and internalizing behaviors at baseline moderate the relationship between JS+CS practices and improvements in children’s protective factors over time, relative to the active control?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Demographics

2.3.2. Child Protective Factors

2.3.3. Child Externalizing and Internalizing Behaviors

2.3.4. Teacher Implementation of JS+CS Model

2.3.5. Teacher Self-Efficacy

2.3.6. Teacher Stress

2.4. Procedures

2.4.1. Jump Start Plus COVID Support (JS+CS)

2.4.2. Healthy Caregivers–Healthy Children (HC2)

2.5. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effectiveness of JS+CS

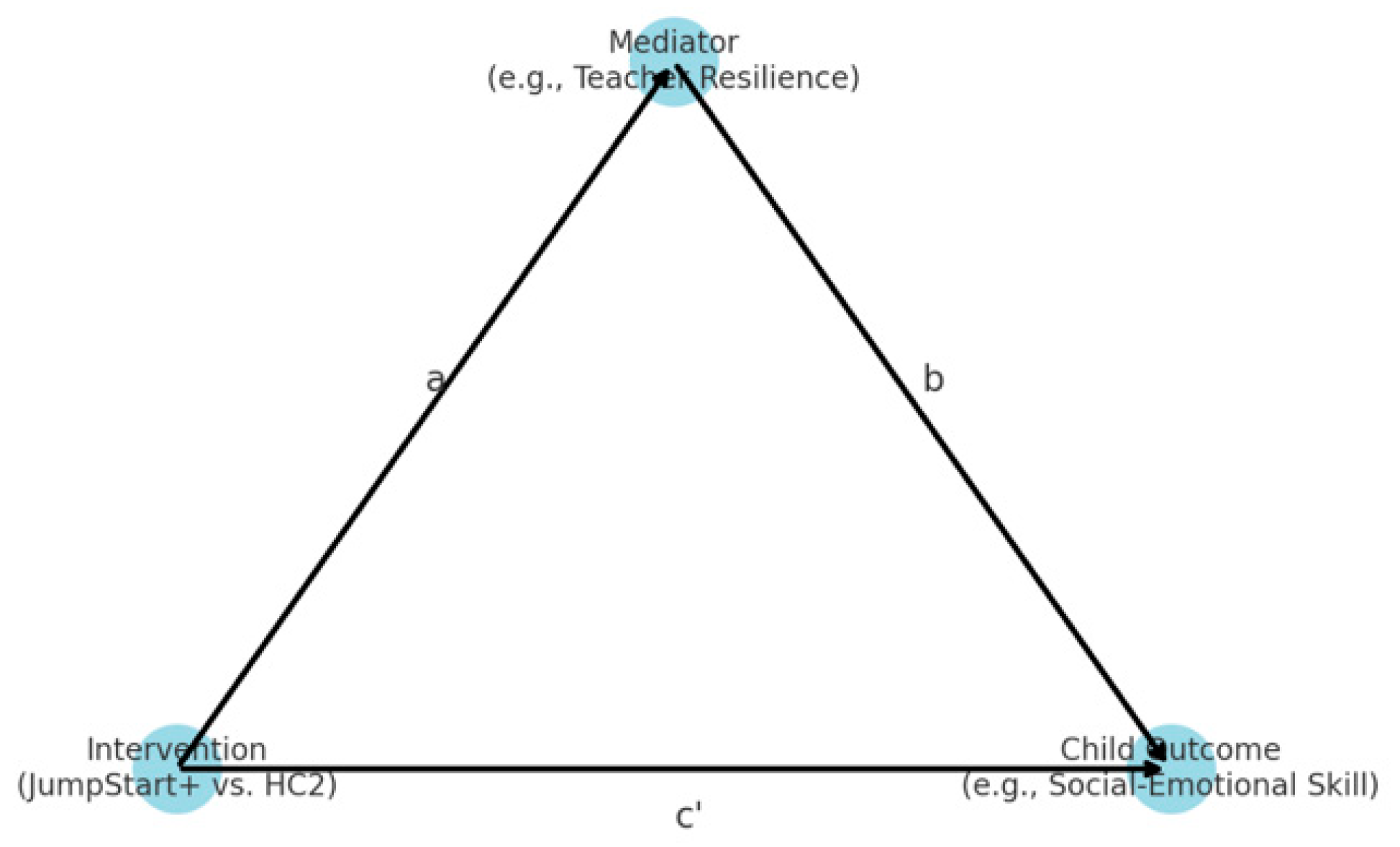

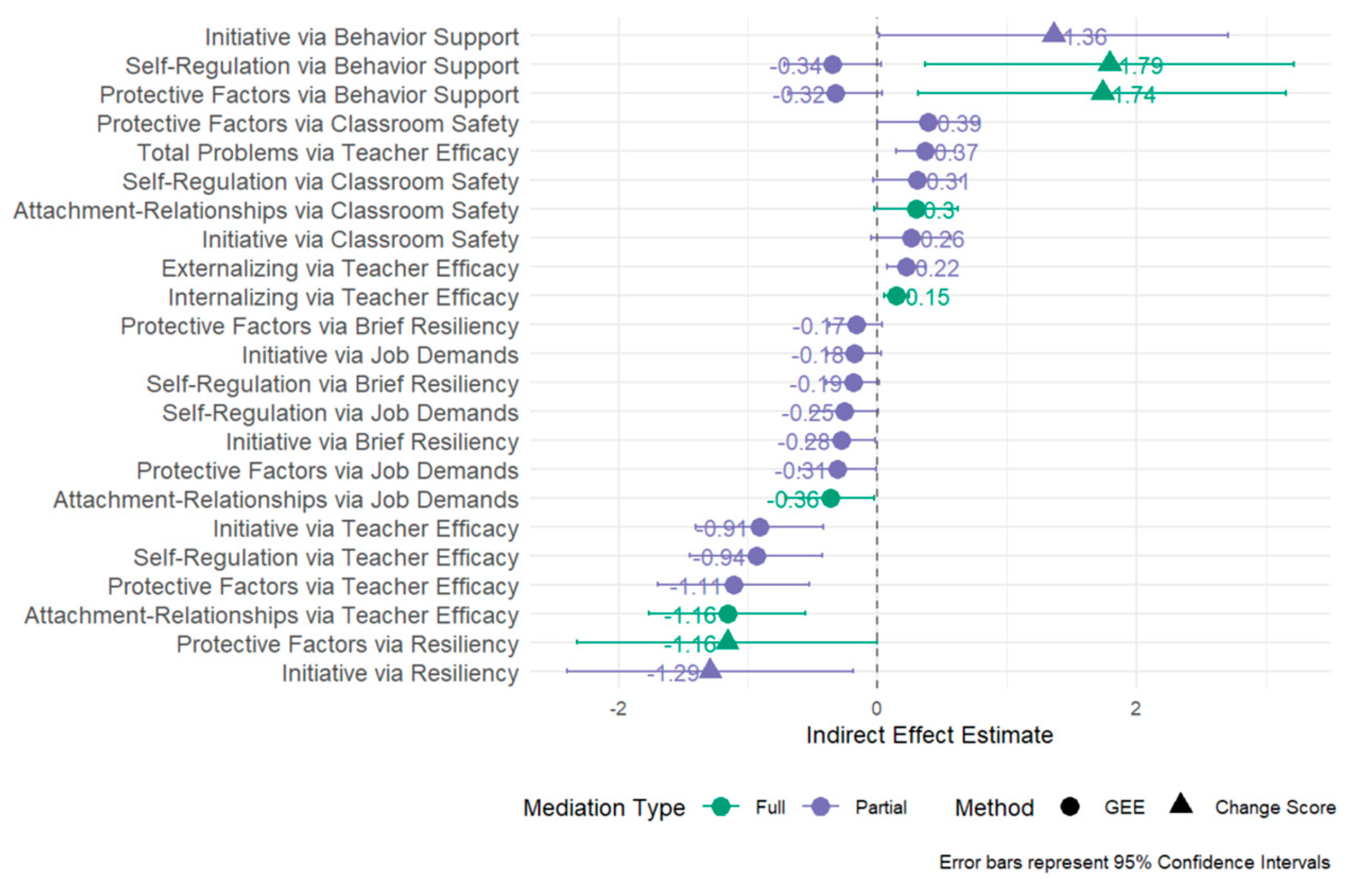

3.2. Mediator Analyses

3.3. Mediation Analysis: Change Score Models

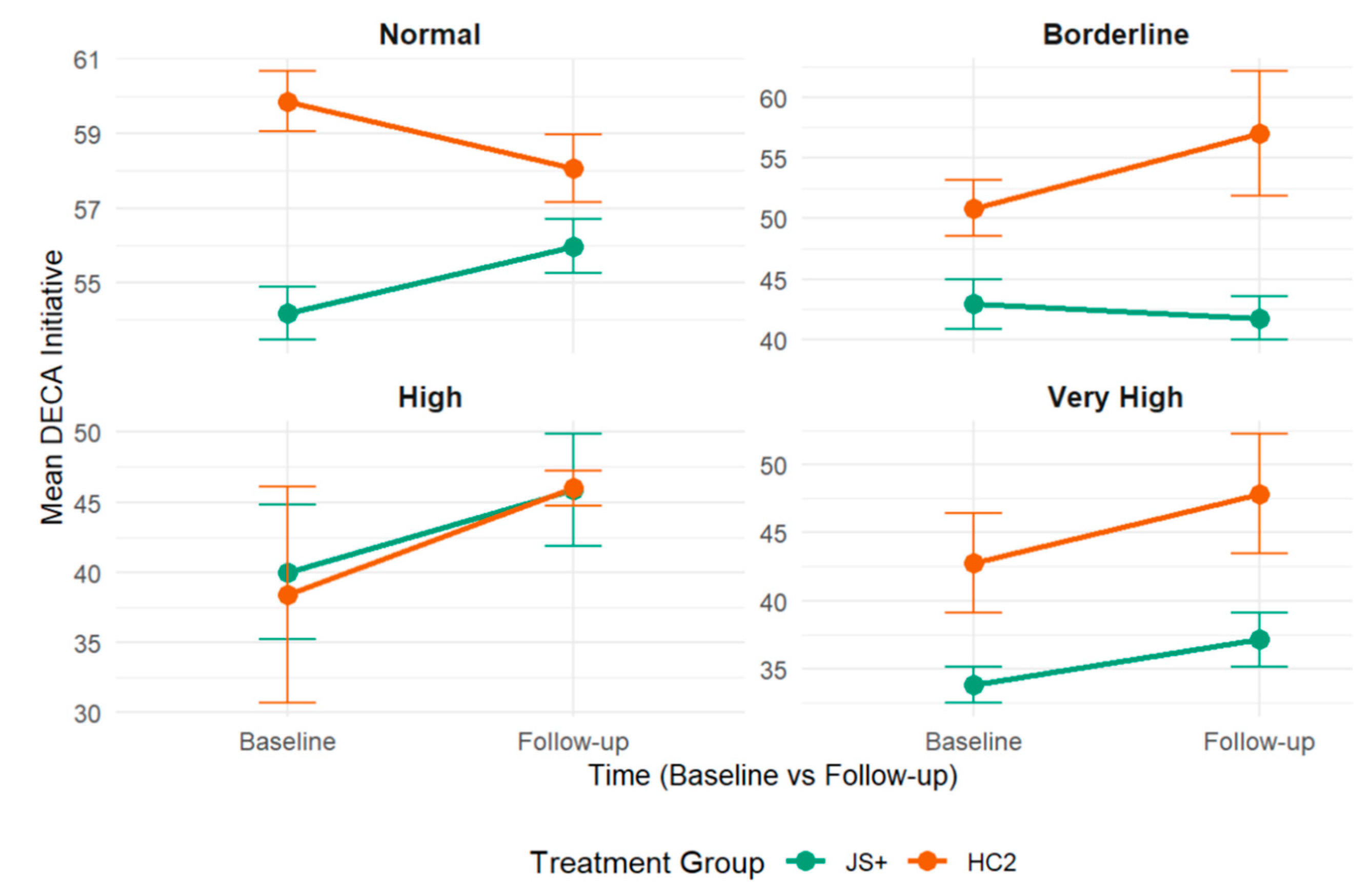

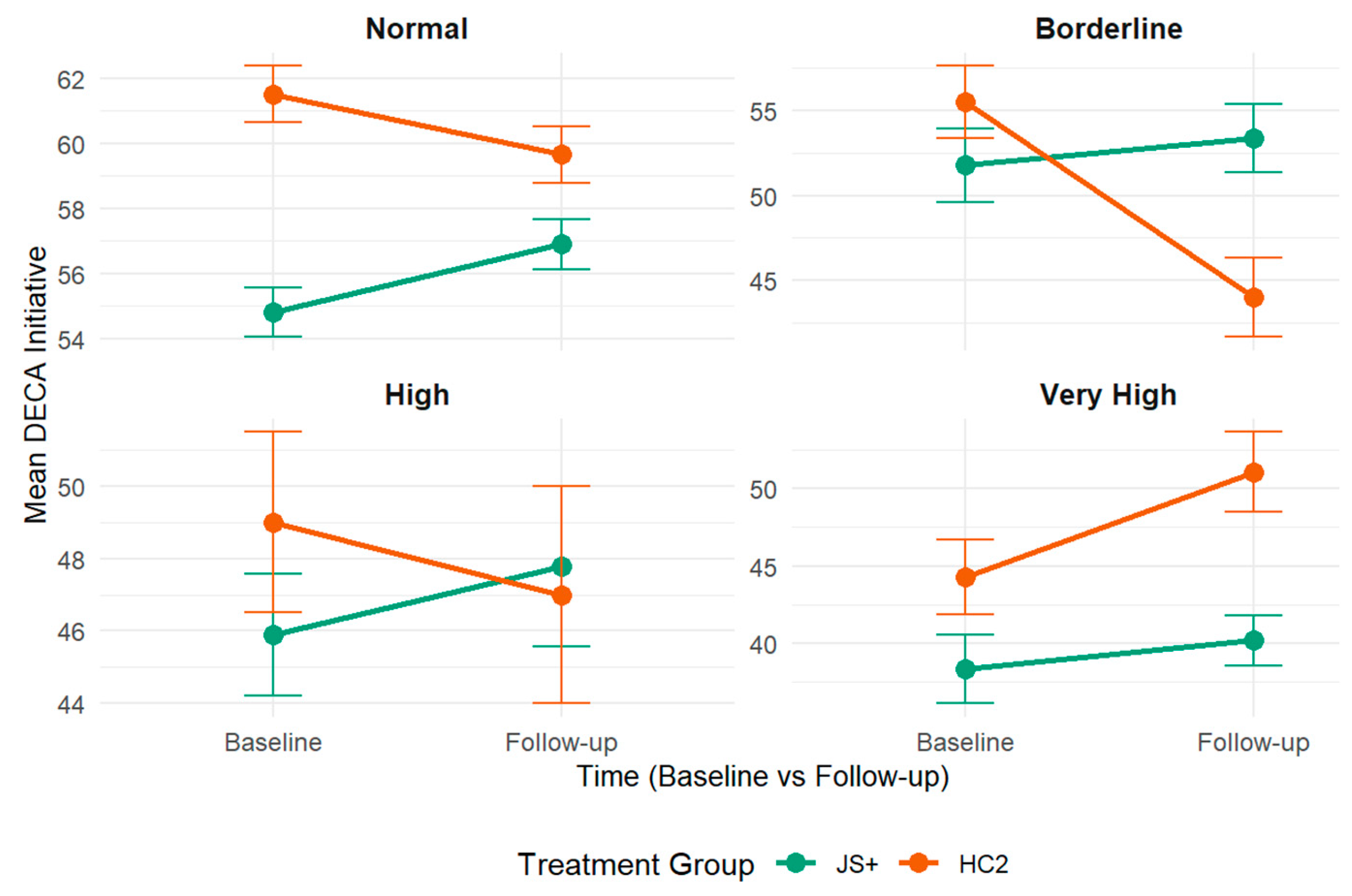

3.4. Moderator Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Child Protective Factors Mediated by Teacher Stress, Classroom Practices, and Self-Efficacy

4.2. Children’s Problematic Behaviors Mediated by Teacher Stress, Classroom Practices, and Self-Efficacy

4.3. Children’s Protective Factors Moderated by Children’s Externalizing and Internalizing Behaviors

4.4. Limitations

4.5. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| DECA | Devereux Early Childhood Assessment |

| ECE | Early care and education |

| GEE | Generalized estimating equation |

| HC2 | Healthy Caregivers–Healthy Children |

| HERS-C | Health Environment Rating Scale-Classroom |

| IECMHC | Infant and early childhood mental health consultation |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| JS+CS | Jump Start Plus COVID Support |

| SDQ | Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire |

References

- Institute of Medicine; National Research Council. From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; p. 608. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, C.M.; Carlson, J.; Alvira-Hammond, M. Federal Policies can Address the Impact of Structural Racism on Black Families’ Access to Early Care and Education; ED614026; Institute of Educational Sciences: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2021; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Bocknek, E.L.; Iruka, I.U.; Brophy-Herb, H.E.; Stokes, K.; Johnson, A.L. Belongingness as the Foundation of Social and Emotional Development: Focus on Black Infants, Toddlers, and Young Children; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Churchill, K.E.; Lippman, L. Early childhood social and emotional development: Advancing the field of measurement. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 45, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.M.; Zaslow, M.; Darling-Churchill, K.E.; Halle, T.G. Assessing early childhood social and emotional development: Key conceptual and measurement issues. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 45, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.A.; Lowenstein, A.E. Early Care, Education, and Child Development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2011, 62, 483–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson-Staub, C. Equity Starts Early: Addressing Racial Inequities in Child Care and Early Education Policy; Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP): Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Capizzano, J.A.; Main, R. Many Young Children Spend Long Hours in Child Care; No. 22; Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, T.K.; Kuvalanka, K.A. Behavior problems in child care classrooms: Insights from child care teachers. Prev. Sch. Fail. Altern. Educ. Child. Youth 2019, 63, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondi, C.F.; Rihal, T.K.; Magro, S.W.; Kerber, S.; Carlson, E.A. Childcare providers’ views of challenging child behaviors, suspension, and expulsion: A qualitative analysis. Infant Ment. Health J. 2022, 43, 695–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliam, W.S.; Shahar, G. Preschool and Child Care Expulsion and Suspension: Rates and Predictors in One State. Infants Young Child. 2006, 19, 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders-Phillips, K.; Settles-Reaves, B.; Walker, D.; Brownlow, J. Social inequality and racial discrimination: Risk factors for health disparities in children of color. Pediatrics 2009, 124, S176–S186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Education. 2013–2014 Civil Rights Data Collection: A First Look; Office for Civil Rights: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, S.; Corr, C.P.; O’Grady, C.; Guan, Y. Adverse childhood experiences and preschool suspension expulsion: A population study. Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 97, 104149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, J.H.; Devore, C.D.; Allison, M.; Ancona, R.; Barnett, S.E.; Gunther, R.; Holmes, B.; Lamont, J.H.; Minier, M.; Okamoto, J.K.; et al. Out-of-School Suspension and Expulsion. Pediatrics 2013, 131, e1000–e1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, E.; Hartz, K.; Berkowitz, M.; Carlson, A.; Kimport, R.; Brown, C.; Biel, M.G.; Domitrovich, C.E. Using early childhood mental health consultation to facilitate the social–emotional competence and school readiness of preschool children in marginalized communities. Sch. Ment. Health 2022, 14, 608–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natale, R.; Kolomeyer, E.; Futterer, J.; Mahmoud, F.D.; Schenker, M.; Robleto, A.; Horen, N.; Spector, R. Infant and early childhood mental health consultation in a diverse metropolitan area. Infant Ment. Health J. 2022, 43, 440–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iruka, I.U.; Harper, K.; Lloyd, C.M.; Boddicker-Young, P.; De Marco, A.; Jarvis, B. Anti-Racist Policymaking to Protect, Promote, and Preserve Black Families and Babies; Equity Research Action Coalition; Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bingham, G.E.; Phelps, C.; Dean, M.P. Examining The Preschool to First-Grade Literacy and Language Outcomes of Black Children Experiencing a High-Quality Early Childhood Program. Elem. Sch. J. 2023, 123, 367–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, U.; Salazar De Pablo, G.; Franco, M.; Moreno, C.; Parellada, M.; Arango, C.; Fusar-Poli, P. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on child and adolescent mental health: Systematic review. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 32, 1151–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penna, A.L.; de Aquino, C.M.; Pinheiro, M.S.N.; do Nascimento, R.L.F.; Farias-Antúnez, S.; Araújo, D.A.B.S.; Mita, C.; Machado, M.M.T.; Castro, M.C. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal mental health, early childhood development, and parental practices: A global scoping review. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of the Surgeon General (OSG). Protecting Youth Mental Health: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory; US Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary & Trends Report: 2013–2023; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, L.; Hemmeter, M.L. A programwide model for supporting social emotional development and addressing challenging behavior in early childhood settings. In Handbook of Positive Behavior Support; Sailor, W., Dunlap, G., Sugai, G., Horner, R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 177–202. [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam, W.S.; Maupin, A.N.; Reyes, C.R. Early childhood mental health consultation: Results of a statewide random-controlled evaluation. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 55, 754–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvard Global Health Institute. The Path to Zero: Key Metrics for COVID Suppression–Pandemics Explain. Available online: https://globalepidemics.org/key-metrics-for-covid-suppression/ (accessed on 21 April 2024).

- Lopez, Y. ’Like Paying for a Luxury Car’: Childcare Costs in Miami Are Holding Families Back. Miami Herald. Available online: https://www.miamiherald.com/news/business/article248956749.html (accessed on 28 March 2021).

- Lingras, K.A.; Mrozinski, K.; Clavin, A.; Handevidt, A.; Moberg, L.; Michaels, C.; Mischke, M.; Schreifels, T.; Fallon, M. Guidelines for 0–3 Childcare During COVID-19: Balancing Physical Health and Safety with Social Emotional Development. Available online: https://perspectives.waimh.org/2021/03/19/guidelines-for-0-3-childcare-during-covid-19-balancing-physical-health-and-safety-with-social-emotional-development/ (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Gilliam, W.S.; Malik, A.A.; Shafiq, M.; Klotz, M.; Reyes, C.; Humphries, J.E.; Murray, T.; Elharake, J.A.; Wilkinson, D.; Omer, S.B. COVID-19 Transmission in US Child Care Programs. Pediatrics 2021, 147, e2020031971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A.C.; Higgins, M.; Singer, S.; Weiner, J. Understanding Psychological Safety in Health Care and Education Organizations: A Comparative Perspective. Res. Hum. Dev. 2016, 13, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souto-Manning, M.; Melvin, S.A. Early Childhood Teachers of Color in New York City: Heightened stress, lower quality of life, declining health, and compromised sleep amidst COVID-19. Early Child. Res. Q. 2022, 60, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilinski, B.; Morley, A.; Wu, J.H.-C. From “Survival Mode” to “#winning”: Michigan Pre-K Teachers’ Experiences During the First Year of COVID-19. Early Child. Educ. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, K. Young children’s behaviour and contextual risk factors in the UK. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 39, 1230–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, R.C.; Dearth-Wesley, T.; Gooze, R.A. Workplace stress and the quality of teacher–children relationships in Head Start. Early Child. Res. Q. 2015, 30, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinsser, K.M.; Silver, H.C.; Shenberger, E.R.; Jackson, V. A Systematic Review of Early Childhood Exclusionary Discipline. Rev. Educ. Res. 2022, 92, 743–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natale, R.; Agosto, Y.; Shearer, R.J.B.; George, S.M.S.; Jent, J. Designing a virtual mental health consultation program to support and strengthen childcare centers impacted by COVID-19: A randomized controlled trial protocol. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2023, 124, 107022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, A.E.; Perry, D.F. Healthy Futures: Evaluation of Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation by the District of Columbia Department of Behavioral Health; Georgetown Univer Center for Child and Human Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, A.; Davis, A.; Perry, D.F.; Jones, W. The Georgetown Model of Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation: For School-Based Settings; Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological models of human development. In Readings on the Development of Children, 2nd ed.; Gauvain, M., Cole, M., Eds.; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1994; Volume 1, pp. 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, H.C.; Davis Schoch, A.E.; Loomis, A.M.; Park, C.E.; Zinsser, K.M. Updating the evidence: A systematic review of a decade of Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation (IECMHC) research. Infant Ment. Health J. 2023, 44, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuyk, M.A.; Sprague-Jones, J.; Reed, C. Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation: An Evaluation of Effectiveness in a Rural Community. Infant Ment. Health J. 2016, 37, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center of Excellence for Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation. The Evidence Base for Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation (IECMHC). Available online: http://www.iecmhc.org/documents/CoE-Evidence-Synthesis.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Mondi, C.F. Supporting social and emotional learning through infant and early childhood mental health consultation. Soc. Emot. Learn. Res. Pract. Policy 2025, 5, 100084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, C.S.; Denham, S.A.; Curby, T.W.; Bassett, H.H. Emotional and organizational supports for preschoolers’ emotion regulation: Relations with school adjustment. Emotion 2016, 16, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulotsky-Shearer, R.J.; Fernandez, V.A.; Bichay-Awadalla, K.; Bailey, J.; Futterer, J.; Qi, C.H. Teacher-child interaction quality moderates social risks associated with problem behavior in preschool classroom contexts. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 67, 101103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curby, T.W.; Rudasill, K.M.; Edwards, T.; Pérez-Edgar, K. The role of classroom quality in ameliorating the academic and social risks associated with difficult temperament. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2011, 26, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, D.F.; Allen, M.D.; Brennan, E.M.; Bradley, J.R. The evidence base for mental health consultation in early childhood settings: A research synthesis addressing children’s behavioral outcomes. Early Educ. Dev. 2010, 21, 795–824. [Google Scholar]

- Duran, F.B.; Hepburn, K.S.; Kaufmann, R.K.; Le, L.T.; Allen, M.D.; Brennan, E.M.; Green, B.L. Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation; Center on the Social and Emotional Foundations for Early Learning: Nashville, TN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mackrain, M.; LeBuffe, P.; Powell, G. Devereux Early Childhood Assessment for Infants and Toddlers; Kaplan Early Learning Company: Lewisville, NC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- LeBuffe, P.A.; Naglieri, J.A. The Devereux Early Childhood Assessment for Preschoolers, Second Edition (DECA-P2) Assessment, Technical Manual, and User’s Guide; Kaplan: Lewisville, NC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- LeBuffe, P.A.; Naglieri, J.A. The Devereux Early Childhood Assessment (DECA): A measure of within-child protective factors in preschool children. NHSA Dialog 1999, 3, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naglieri, J.A.; LeBuffe, P.A.; Shapiro, V.B. Assessment of social-emotional competencies related to resilience. In Handbook of Resilience in Children; Goldstein, S.B.R., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2013; pp. 215–225. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, J.; Mincic, M.; Winsler, A. Parent–teacher agreement and the reliability of the Devereux Early Childhood Assessment (DECA) for English- and Spanish-speaking, ethnically diverse children living in poverty. In Self-Regulation and Early School Success, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 115–129. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, S.; Sanders, L.M.; Uhlhorn, S.; Natale, R. Health Promotion in Child-Care Centers: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. In Proceedings of the Pediatric Academic Societies 2011 Annual Meeting, Platform Presentation (CTSA Student Research Award), Denver, CO, USA, 30 April–3 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1997, 38, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Caring for Our Children, National Health and Safety Performance Standards; American Academy of Pediatrics: Itasca, IL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gellar, S.; Lynch, K. Teacher Opinion Survey Revised, Unpublished manuscript; Virginia Commonwealth University Intellectual Property Foundation: Richmond, VA, USA, 1999.

- Sinclair, V.G.; Wallston, K.A. The development and psychometric evaluation of the Brief Resilient Coping Scale. Assessment 2004, 11, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, L.A.; Gurley, D.N.; Sachs, B.; Kryscio, R.J. Psychosocial predictors of maternal depressive symptoms, parenting attitudes, and child behavior in single-parent families. Nurs. Res. 1991, 40, 214–220. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, M.L.; Ashford, K.; Linares, A.M.; Hall, L.A. A pilot test of the Everyday Stressors Index–Spanish version in a sample of Hispanic women attending prenatal care. J. Nurs. Meas. 2015, 23, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curbow, B.; Spratt, K.; Ungaretti, A.; McDonnell, K.; Breckler, S. Development of the child care worker job stress inventory. Early Child. Res. Q. 2000, 15, 515–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jent, J.F.; St. George, S.M.; Agosto, Y.; Rothenberg, W.A.; Howe, E.; Velasquez, C.; Mansoor, E.; Garcia, E.G.; Bulotsky-Shearer, R.J.; Natale, R. Virtual robotic telepresence early childhood mental health consultation to childcare centers in the aftermath of COVID-19: Training approaches and perceived acceptability and usefulness. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1339230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Schools and Childcare Programs Guidance for COVID-19 Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/covid/index.html (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Hemmeter, M.L.; Barton, E.; Fox, L.; Vatland, C.; Henry, G.; Pham, L.; Veguilla, M. Program-wide implementation of the Pyramid Model: Supporting fidelity at the program and classroom levels. Early Child. Res. Q. 2022, 59, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natale, R.A.; Lopez-Mitnik, G.; Uhlhorn, S.B.; Asfour, L.; Messiah, S.E. Effect of a child care center-based obesity prevention program on body mass index and nutrition practices among preschool-aged children. Health Promot. Pract. 2014, 15, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natale, R.A.; Messiah, S.E.; Asfour, L.; Uhlhorn, S.B.; Delamater, A.; Arheart, K.L. Role modeling as an early childhood obesity prevention strategy: Effect of parents and teachers on preschool children’s healthy lifestyle habits. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2014, 35, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natale, R.A.; Messiah, S.E.; Asfour, L.S.; Uhlhorn, S.B.; Englebert, N.E.; Arheart, K.L. Obesity prevention program in childcare centers: Two-year follow-up. Am. J. Health Promot. 2017, 31, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H. Tidyverse: Easily Install and Load the Tidyverse. Available online: https://tidyverse.tidyverse.org (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balise, R.; Odom, G.; Grealis, K.; Cardozo, F. rUM: R Templates from the University of Miami. Available online: https://raymondbalise.github.io/rUM/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Rich, B. Table1: Tables of Descriptive Statistics in HTML. Available online: https://github.com/benjaminrich/table1 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Dassa, L.; Nichols, B. Policy implications of infant mental health. Infant Ment. Health J. 2019, 40, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natale, R.; Howe, B.; Valesquez, C.; Guzman Garcia, E.; Granja, K.; Caceres, B.; Erban, E.; Ramirez, T.; Jent, J. Co-Designing an Infant Early Childhood Mental Health Mobile App for Early Care and Education Teachers Professional Development: A Community-Based Participatory Research Approach. JMIR Form. Res. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Carson, V.; Lee, E.-Y.; Hewitt, L.; Jennings, C.; Hunter, S.; Kuzik, N.; Stearns, J.A.; Unrau, S.P.; Poitras, V.J.; Gray, C.; et al. Systematic review of the relationships between physical activity and health indicators in the early years (0–4 years). BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 33–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accavitti, M.R.; Williford, A.P. Teacher perceptions of externalizing behaviour subtypes in preschool: Considering racial factors. Early Child Dev. Care 2022, 192, 932–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natale, R.A.; Kolomeyer, E.; Robleto, A.; Jaffery, Z.; Spector, R. Utilizing the RE-AIM framework to determine effectiveness of a preschool intervention program on social-emotional outcomes. Eval. Program Plan. 2020, 79, 101773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | JS+CS (n = 287) | HC2 (n = 317) | Total (N = 608) | Test Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.59 (1.18) | 3.34 (1.15) | 3.46 (1.17) | F(1, 606) = 7.37 | 0.007 |

| Gender | χ2(1) = 7.23 | 0.007 | |||

| Female | 160 (55.7%) | 142 (44.8%) | 302 (50.0%) | ||

| Male | 127 (44.3%) | 175 (55.2%) | 302 (50.0%) | ||

| Race | χ2(5) = 13.25 | 0.021 | |||

| White | 206 (74.1%) | 198 (64.5%) | 404 (69.1%) | ||

| Black | 48 (17.3%) | 87 (28.3%) | 135 (23.1%) | ||

| Native | 4 (1.4%) | 4 (1.3%) | 8 (1.4%) | ||

| American | |||||

| Asian Pacific | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.2%) | ||

| Islander | |||||

| Multiracial | 14 (5.0%) | 9 (2.9%) | 23 (3.9%) | ||

| Other | 5 (1.8%) | 9 (2.9%) | 14 (2.4%) | ||

| Ethnicity | χ2(4) = 20.62 | <0.001 | |||

| Hispanic | 238 (83.8%) | 217 (68.9%) | 455 (76.0%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 11 (3.9%) | 16 (5.1%) | 27 (4.5%) | ||

| White | |||||

| Non-Hispanic | 24 (8.5%) | 60 (19.0%) | 84 (14.0%) | ||

| Black | |||||

| Haitian | 7 (2.5%) | 18 (5.7%) | 25 (4.2%) | ||

| Other | 4 (1.4%) | 4 (1.3%) | 8 (1.3%) | ||

| English Proficiency | χ2(1) = 4.90 | 0.027 | |||

| Yes | 174 (61.5%) | 218 (70.1%) | 392 (66.0%) | ||

| No | 109 (38.5%) | 93 (29.9%) | 202 (34.0%) | ||

| Primary Language | χ2(2) = 16.63 | <0.001 | |||

| English | 90 (31.6%) | 151 (47.6%) | 241 (40.0%) | ||

| Spanish | 194 (68.1%) | 164 (51.7%) | 358 (59.5%) | ||

| Creole | 1 (0.4%) | 2 (0.6%) | 3 (0.5%) | ||

| Secondary Language | χ2(3) = 8.45 | 0.038 | |||

| English | 173 (65.5%) | 149 (55.6%) | 322 (60.5%) | ||

| Spanish | 80 (30.3%) | 95 (35.4%) | 175 (32.9%) | ||

| Creole | 8 (3.0%) | 14 (5.2%) | 22 (4.1%) | ||

| Other | 3 (1.1%) | 10 (3.7%) | 13 (2.4%) |

| Characteristic | JS+CS (n = 86) | HC2 (n = 104) | Total (n = 190) | Test Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 46.09 (12.58) | 42.94 (13.67) | 44.39 (13.24) | F(1, 184) = 2.65 | 0.105 |

| Gender | χ2(1) = 0.06 | 0.811 | |||

| Female | 84 (97.7%) | 101 (97.1%) | 185 (97.4%) | ||

| Male | 2 (2.3%) | 3 (2.9%) | 5 (2.6%) | ||

| Race | χ2(4) = 1.71 | 0.79 | |||

| White | 66 (76.7%) | 74 (72.5%) | 140 (74.5%) | ||

| Black | 12 (14.0%) | 21 (20.6%) | 33 (17.6%) | ||

| Native American | 1 (1.2%) | 1 (1.0%) | 2 (1.1%) | ||

| Multiracial | 4 (4.7%) | 3 (2.9%) | 7 (3.7%) | ||

| Other | 3 (3.5%) | 3 (2.9%) | 6 (3.2%) | ||

| Ethnicity | χ2(2) = 10.03 | 0.007 | |||

| Hispanic | 76 (90.5%) | 81 (77.9%) | 157 (83.5%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 1 (1.2%) | 7 (6.7%) | 8 (4.3%) | ||

| White | |||||

| Non-Hispanic | 3 (3.6%) | 9 (8.7%) | 12 (6.4%) | ||

| Black | |||||

| Haitian | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (4.8%) | 5 (2.7%) | ||

| Other | 4 (4.8%) | 2 (1.9%) | 6 (3.2%) | ||

| English Proficiency | χ2(1) = 6.53 | 0.011 | |||

| Yes | 32 (37.2%) | 57 (55.9%) | 89 (47.3%) | ||

| No | 54 (62.8%) | 45 (44.1%) | 99 (52.7%) | ||

| Secondary Language | χ2(3) = 6.74 | 0.081 | |||

| English | 48 (64.0%) | 44 (51.2%) | 92 (57.1%) | ||

| Spanish | 21 (28.0%) | 28 (32.6%) | 49 (30.4%) | ||

| Creole | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (7.0%) | 6 (3.7%) | ||

| Other | 6 (8.0%) | 8 (9.3%) | 14 (8.7%) | ||

| Education Level | χ2(7) = 6.86 | 0.443 | |||

| Elementary or | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.0%) | 1 (0.5%) | ||

| Less | |||||

| Some High School | 2 (2.4%) | 3 (2.9%) | 5 (2.7%) | ||

| High School/GED | 16 (19.5%) | 19 (18.4%) | 35 (18.9%) | ||

| Technical | 9 (11.0%) | 4 (3.9%) | 13 (7.0%) | ||

| Training | |||||

| Some College | 15 (18.3%) | 21 (20.4%) | 36 (19.5%) | ||

| Associate Degree | 8 (9.8%) | 14 (13.6%) | 22 (11.9%) | ||

| Bachelor’s Degree | 25 (30.5%) | 37 (35.9%) | 62 (33.5%) | ||

| Graduate Degree | 7 (8.5%) | 4 (3.9%) | 11 (5.9%) | ||

| Professional Experience | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | ||

| Years as Childcare Professional | 11.30 (10.18) | 11.24 (8.40) | 11.27 (9.17) | F(1, 162) = 0.00 | 0.967 |

| Years at Current Program | 8.59 (8.75) | 6.28 (7.01) | 7.28 (7.87) | F(1, 139) = 3.03 | 0.084 |

| Children Enrolled in Classroom | 13.39 (6.15) | 12.13 (5.61) | 12.70 (5.88) | F(1, 187) = 2.14 | 0.145 |

| JS+CS (Intervention) | HC2 (Comparison) | Effect | Estimate | Std. Error | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (N = 304) | Follow-Up (N = 304) | Baseline (N = 367) | Follow-Up (N = 367) | |||||

| DECA Total Protective Factors | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 51.5 (10.7) | 53.1 (10.1) | 55.6 (12.5) | 57.1 (10.5) | Treatment (JS+CS) | −5.3576 | 1.065 | <0.0001 |

| Missing | 82 (27.0%) | 104 (34.2%) | 137 (37.3%) | 213 (58.0%) | Time (Follow-Up vs. Baseline) | 1.9311 | 0.8948 | 0.0309 |

| Interaction (JS+CS × Follow-Up) | 0.199 | 1.2054 | 0.8689 | |||||

| DECA Attachment/Relationships | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 49.3 (11.2) | 51.8 (9.58) | 50.5 (11.9) | 53.7 (10.5) | Treatment (JS+CS) | −2.4879 | 0.9724 | 0.0105 |

| Missing | 67 (22.0%) | 90 (29.6%) | 116 (31.6%) | 187 (51.0%) | Time (Follow-Up vs. Baseline) | 3.8329 | 0.818 | <0.0001 |

| Interaction (JS+CS × Follow-Up) | −0.864 | 1.1522 | 0.4533 | |||||

| DECA Self-Regulation | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 52.8 (10.6) | 52.9 (10.1) | 56.2 (11.9) | 56.0 (10.6) | Treatment (JS+CS) | −4.1818 | 1.0208 | <0.0001 |

| Missing | 64 (21.1%) | 88 (28.9%) | 126 (34.3%) | 192 (52.3%) | Time (Follow-Up vs. Baseline) | 0.3181 | 0.8269 | 0.7004 |

| Interaction (JS+CS × Follow-Up) | 0.1974 | 1.1162 | 0.8596 | |||||

| DECA Initiative | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 51.2 (10.9) | 53.4 (10.7) | 56.7 (12.0) | 56.7 (10.5) | Treatment (JS+CS) | −6.5743 | 1.0586 | <0.0001 |

| Missing | 70 (23.0%) | 91 (29.9%) | 119 (32.4%) | 196 (53.4%) | Time (Follow-Up vs. Baseline) | 0.606 | 0.8869 | 0.4945 |

| Interaction (JS+CS × Follow-Up) | 1.9162 | 1.1374 | 0.0921 | |||||

| SDQ Total Problems | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 7.99 (5.88) | 7.79 (5.95) | 6.65 (6.18) | 5.85 (5.87) | Treatment (JS+CS) | 2.0777 | 0.5232 | <0.0001 |

| Missing | 74 (24.3%) | 88 (28.9%) | 101 (27.5%) | 181 (49.3%) | Time (Follow-Up vs. Baseline) | −0.4308 | 0.4098 | 0.2932 |

| Interaction (JS+CS × Follow-Up) | −0.0408 | 0.5574 | 0.9416 | |||||

| SDQ Externalizing | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 5.36 (4.25) | 5.18 (4.08) | 4.13 (4.07) | 3.69 (3.86) | Treatment (JS+CS) | 1.6939 | 0.3659 | <0.0001 |

| Missing | 74 (24.3%) | 88 (28.9%) | 101 (27.5%) | 181 (49.3%) | Time (Follow-Up vs. Baseline) | −0.1869 | 0.289 | 0.5178 |

| Interaction (JS+CS × Follow-Up) | −0.2006 | 0.3936 | 0.6102 | |||||

| SDQ Internalizing | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.63 (2.57) | 2.62 (2.51) | 2.53 (2.69) | 2.16 (2.60) | Treatment (JS+CS) | 0.3805 | 0.2245 | 0.0901 |

| Missing | 74 (24.3%) | 88 (28.9%) | 101 (27.5%) | 181 (49.3%) | Time (Follow-Up vs. Baseline) | −0.2309 | 0.1903 | 0.225 |

| Interaction (JS+CS × Follow-Up) | 0.1561 | 0.2568 | 0.5433 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Natale, R.; Kenworthy LaMarca, T.; Pan, Y.; Howe, E.; Agosto, Y.; Bulotsky-Shearer, R.J.; St. George, S.M.; Rahman, T.; Velasquez, C.; Jent, J.F. Strengthening Early Childhood Protective Factors Through Safe and Supportive Classrooms: Findings from Jump Start + COVID Support. Children 2025, 12, 812. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070812

Natale R, Kenworthy LaMarca T, Pan Y, Howe E, Agosto Y, Bulotsky-Shearer RJ, St. George SM, Rahman T, Velasquez C, Jent JF. Strengthening Early Childhood Protective Factors Through Safe and Supportive Classrooms: Findings from Jump Start + COVID Support. Children. 2025; 12(7):812. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070812

Chicago/Turabian StyleNatale, Ruby, Tara Kenworthy LaMarca, Yue Pan, Elizabeth Howe, Yaray Agosto, Rebecca J. Bulotsky-Shearer, Sara M. St. George, Tanha Rahman, Carolina Velasquez, and Jason F. Jent. 2025. "Strengthening Early Childhood Protective Factors Through Safe and Supportive Classrooms: Findings from Jump Start + COVID Support" Children 12, no. 7: 812. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070812

APA StyleNatale, R., Kenworthy LaMarca, T., Pan, Y., Howe, E., Agosto, Y., Bulotsky-Shearer, R. J., St. George, S. M., Rahman, T., Velasquez, C., & Jent, J. F. (2025). Strengthening Early Childhood Protective Factors Through Safe and Supportive Classrooms: Findings from Jump Start + COVID Support. Children, 12(7), 812. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070812