Development of Language and Pragmatic Communication Skills in Preschool Children with Developmental Language Disorder in a Speech Therapy Kindergarten—A Real-World Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Methods and Analysis of Communication Skills

2.4. Pedagogical Principles

2.5. Video Documentation and Analysis

2.6. Problems Concerning Statistical Analysis

2.7. Significance of Other Influencing Factors

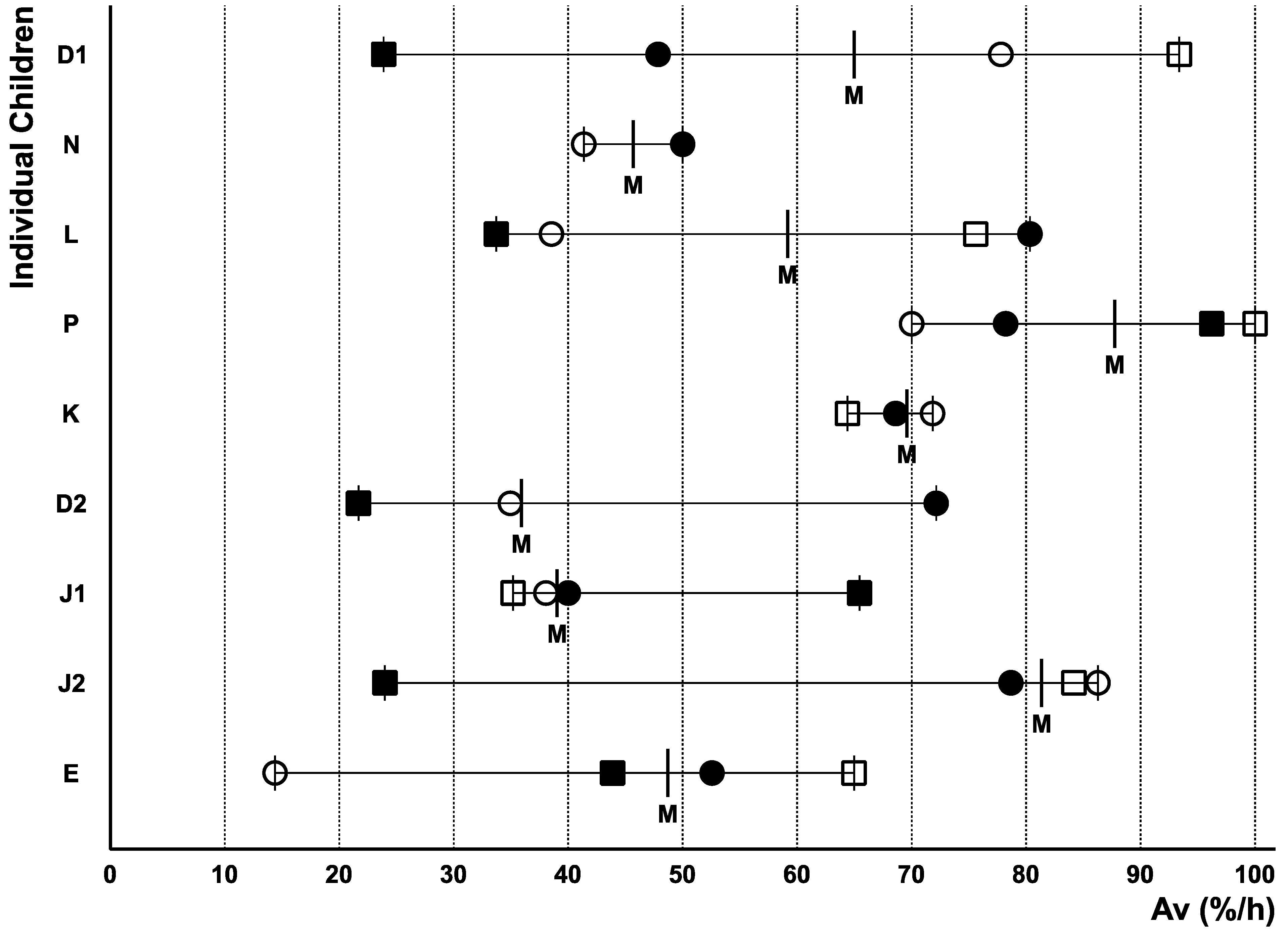

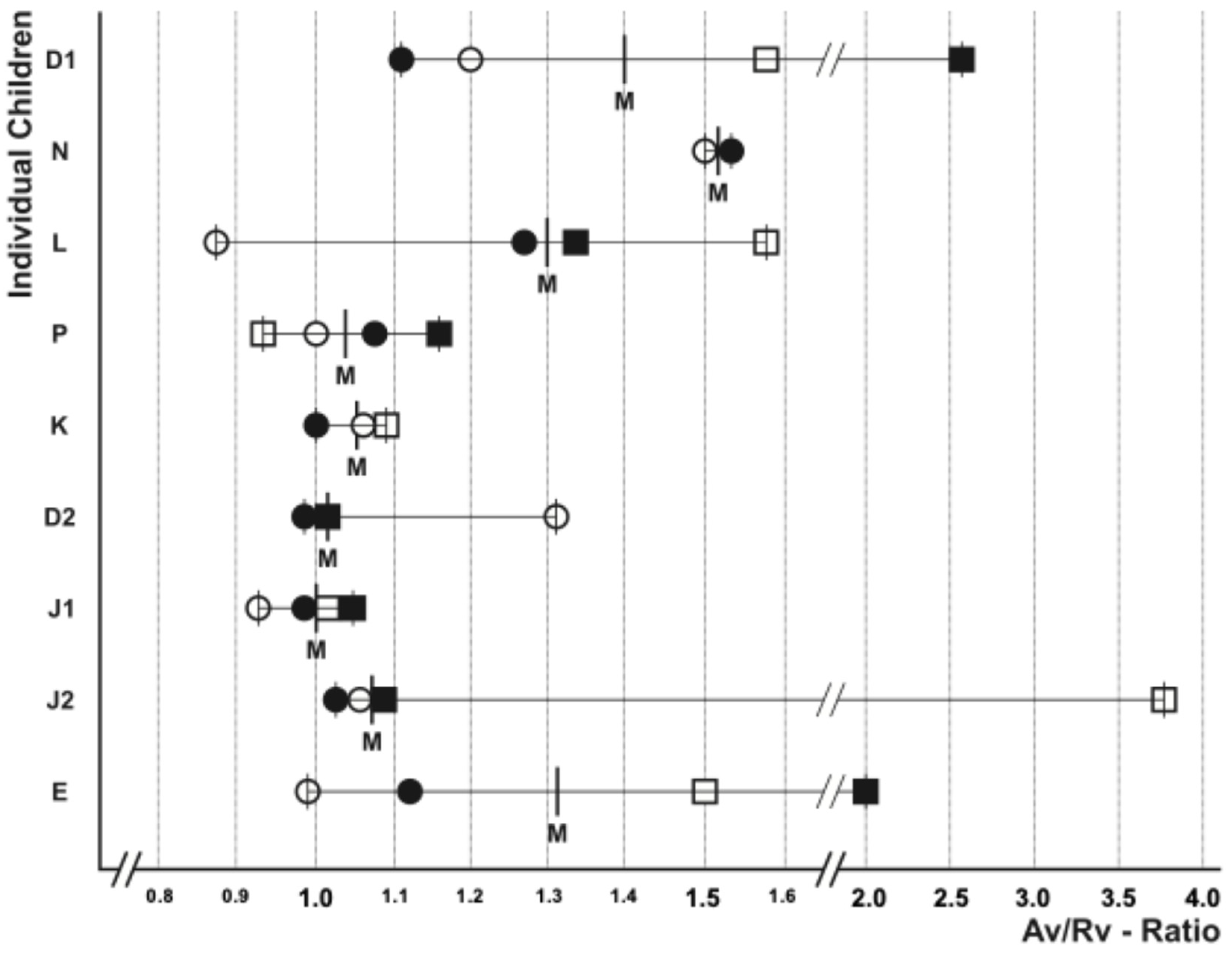

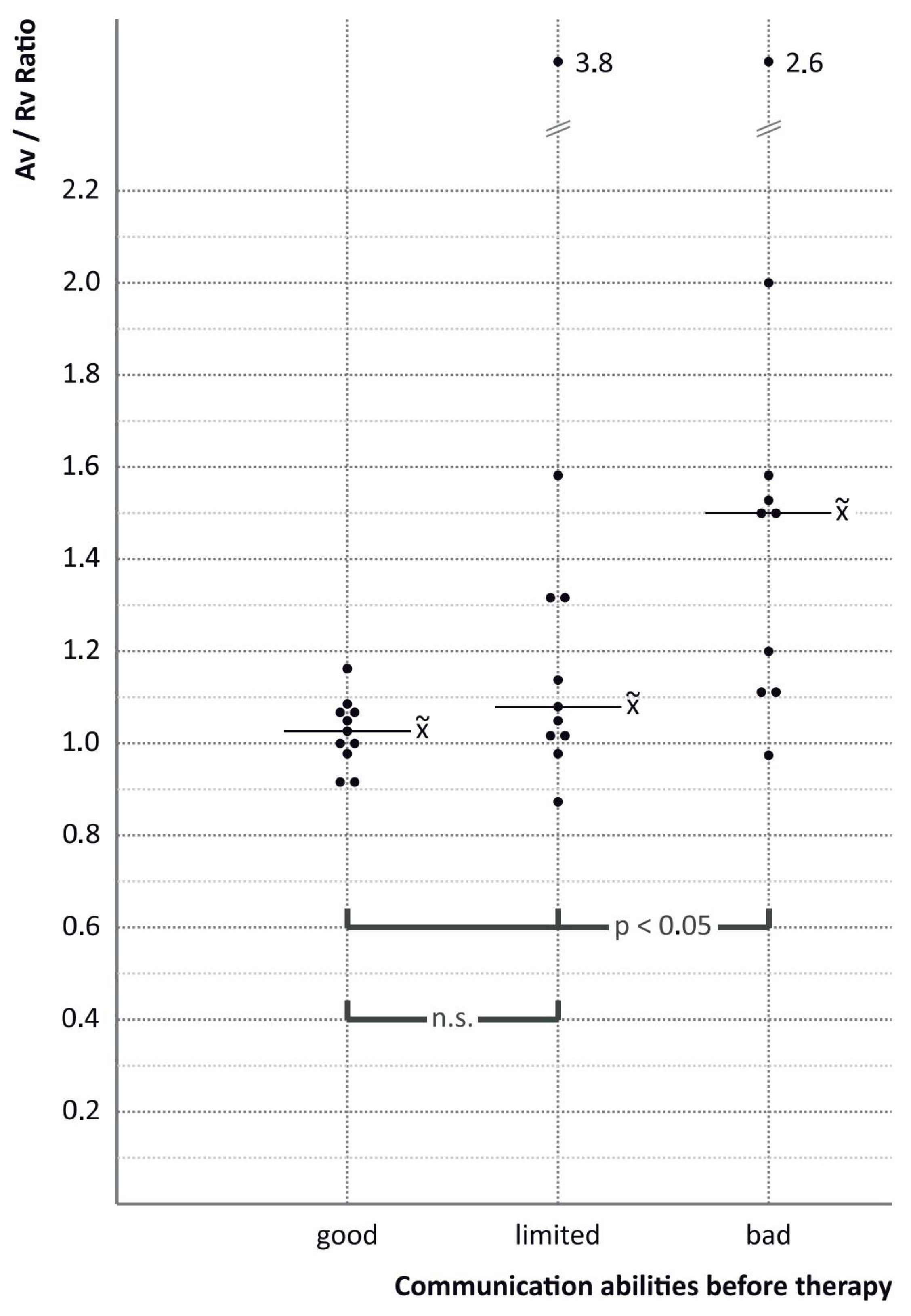

3. Results

4. Discussion

Ethics Considerations of This Study

5. Conclusions

What This Paper Adds

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| D1 B E | N B E | L B E | P B E | K B E | D2 B E | J1 B E | J2 B E | E B E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Articulation | 6 4 | 5 3 | 4 3 | 4 3 | 4 3 | 4 3 | 5 2 | 5 4 | 4 4 |

| Orofacial complex | 4 4 | 4 2 | 3 2 | 4 2 | 3 3 | 3 2 | 3 2 | 4 3 | 1 1 |

| Semantic lexical | 5 5 | 4 3 | 3 1 | 4 3 | 4 3 | 5 3 | 4 1 | 5 1 | 4 4 |

| Grammar Syntax | 6 4 | 6 2 | 4 2 | 4 3 | 5 3 | 5 3 | 4 2 | 4 3 | 5 4 |

| Grammar Morphology | 6 4 | 6 4 | 4 3 | 4 3 | 3 3 | 4 3 | 4 3 | 4 3 | 6 4 |

| Language understanding | 5 4 | 4 2 | 2 1 | 4 3 | 4 3 | 3 2 | 3 1 | 3 1 | 5 3 |

| Auditory Processing | 6 3 | 5 3 | 5 3 | 4 3 | 3 3 | 4 3 | 3 3 | 4 2 | 4 3 |

| Communicative pragmatic | 6 4 | 5 2 | 4 2 | 3 3 | 4 3 | 5 3 | 4 3 | 4 3 | 5 2 |

Appendix B

| Name | IQ | Before Therapy | Age (Years) | After Therapy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practical-Gnostic | Symbolic | Linguistic | Social Communicative | Social Communicative | Linguistic | Symbolic | Practical- Gnostic | |||

| D1 | ↑ | ↓↓ | Ø | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | 6 | ↓↓ | Ø | Ø | Ø |

| N | Ø | Ø | Ø | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | 5 | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | Ø | Ø |

| L | Ø | Ø | Ø | ↓↓ | ↓ | 5 | Ø | ↓↓ | Ø | Ø |

| P | ↓ | Ø | Ø | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | 5 | ↓↓ | Ø | Ø | Ø |

| K | Ø | Ø | Ø | ↓ | Ø | 5 | Ø | ↓ | Ø | Ø |

| D2 | Ø | Ø | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | 5 | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | Ø | Ø | |

| J1 | ↑ | Ø | Ø | Ø | Ø | 5 | Ø | Ø | Ø | Ø |

| J2 | Ø | Ø | ↓↓ | ↓ | 5 | Ø | Ø | Ø | Ø | |

| E | Ø | Ø | ↓ | ↓ | Ø | 4 | Ø | Ø | ↓Ø | Ø |

Appendix C

| Parameters | Assessment Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Below Average | Average | Above Average | |

| Frustration tolerance | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Ability to accept criticism | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Social competence | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Compliance with rules | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Ability to form relationships | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Maximum points | 15 | ||

| Average points | 10 | ||

| Minimum points | 5 | ||

Appendix D

| Child | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | N | L | P | K | D2 | J1 | J2 | E | |

| Frustration tolerance | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Ability to accept criticism | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Social competence | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Compliance with rules | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Ability to form relationships | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Total Points | 9 | 11 | 11 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 7 |

Appendix E. Characterisation of School Types in Germany

References

- Hood, N. Communication in the Early Years: An Introduction. ECE Resources. White, A, Ed. 2019. Available online: https://theeducationhub.org.nz/communication-in-the-early-years-an-introduction (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Hickman, M. The pragmatics of reference in child language: Some issues in developmental theory. In Social and Functional Approaches to Language and Thought; Hickman, M., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 165–184. [Google Scholar]

- Falkum, I.L. Pragmatic development: Learning to use language to communicate. In International Handbook of Language Acquisition; Horst, J.S., von Koss Torkildsen, J., Eds.; Project: Acquiring Figurative Meanings: A Study in Developmental Pragmatics 2018; accessed 10 February 2021; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cutting, A.L.; Dunn, J. Theory of mind, emotion understanding, language and family background: Individual differences and interrelations. Child Dev. 1999, 70, 853–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barron, B. When smart groups fail. J. Learn. Sci. 2003, 12, 307–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoon, I.; Parsons, S.; Rush, R.; Law, J. Childhood language skills and adult literacy: A 29-years follow-up study. Pediatrics 2010, 125, e459–e466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, B.J.; Thomas-Stonell, N.; Rosenbaum, P. Assessing Communicative Participation in Preschool Children with the Focus on the Outcomes of Communication Under Six: A Scoping Review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2020, 63, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, B.J.; Hanna, S.E.; Rosenbaum, P.; Thomas-Stonell, N.; Oddson, B. Factors Contributing to Preschooler’s Communicative Participation Outcomes: Findings from a Population-Based Longitudinal Cohort Study in Ontario, Canada. Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 2018, 27, 737–750. Available online: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/precisepreschoolpubs/7 (accessed on 20 April 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; Text Revision, DSM-5-TR; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF); World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001.

- Levickis, P. Measuring communicative participation in population-based sample of children with speech and language difficulties. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2017, 59, 993–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider-Antrich, P. Entwicklung und Themen früher Peerbeziehungen. Erschienen 2011. Available online: http://www.kita-fachtexte.de (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Andalò, B.; Rigo, F.; Rossi, G.; Majorano, M.; Lavelli, M. Do motor skills impact on language development between 18 and 30 months of age? Infant Behav. Dev. 2022, 66, 101667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piaget, J.; Stöber, N.; Loch, W. Sprechen und Denken des Kindes; Pädagogischer Verlag Schwann: Düsseldorf, Germany, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Zollinger, B. Die Entdeckung der Sprache 1975, 9th ed.; Haupt: Bern, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Alons, E.; Brauner, L.; Luinge, M.; Terwee, C.B.; van Ewijk, L.; Gerrits, E. Review Article Identifying Relevant Concepts for the Development of a Communicative Participation Item Bank for Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Existing Instruments. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2024, 67, 1186–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doove, B.M.; Feron, F.J.M.; van Os, J.; Drukker, M. Preschool Communication: Early Identification of Concerns About Preschool Language Development and Social Participation. Front. Public Health 2021, 8, 546536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, B.J.; Hanna, S.E.; Oddson, B.; Thomas-Stonell, N.; Rosenbaum, P. A population-based study of communicative participation in preschool children with speech-language impairments. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2017, 59, 1049–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martynenko, I. State of Communication Activity of Elder Reschool Children with Developmental Language Disorders. Int. J. Pedagog. Innov. New Technol. 2016, 3, 1207089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas-Stonell, N.; Oddson, B.E.; Robertson, B.; Rosenbaum, P.L. Development of the FOCUS (Focus on the Outcomes of Communication Under Six), a Communication Outcome Measure for Preschool Children. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2010, 52, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flöther, M.; Schlüter, E.; Bruns, T. Multidisciplinary Assessment and management of children with hearing and language disorders—An assessment of the effectiveness of a concept from Lower Saxony, Germany. LOGOS Interdiszip. 2011, 19, 282–292. [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich, D.; Ullrich, K.; Marten, M. A longitudinal assessment of early childhood education with integrated speech therapy for children with significant language impairment in Germany. Int J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2014, 49, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamm, M. Begabung, Kultur und Schule. Mythen, Gegenmythen und Wissenschaftliche Erkenntnisse zu den Grundlagen der Begabtenförderung. Z. Int. Bild. Entwicklungspädagogik 2010, 33, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Stamm, M. Lebenskompetenz Schlägt Intelligenz. Dossier 24/1, Swiss Education 2024. Available online: https://margritstamm.ch/dokumente/dossiers/292-lebenskompetenz-def/file/.html (accessed on 16 July 2024).

- WHO. ICD-10, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision, 5th ed.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Snijders-Oomen. Non-Verbal Intelligence Test SON-R 2,5-7; Hild, P., Winkel, M., Wijnberg-Williams, B., Laros, J., Eds.; Swets & Zeitlinger B.V.: Lisse, The Netherland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Grimme, H. SETK 3-5: Sprachentwicklungstest für 3-5jährige Kinder; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kiese-Himmel, C. AWST-R: Aktiver Wortschatztest für 3-5jährige Kinder; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kauschke, C.; Siegmülle, J. Patholinguistische Diagnostik bei Sprachentwicklungsstörungen, 2nd ed.; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- KABC-II—Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children, 2nd ed.; Kaufman, A.S., Kaufman, N.L., Eds.; Deutsche Bearbeitung Hrsg; Melchers, P., Melchers, M.; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer, R.; Volkamer, M. MOT4-6: Motoriktest für vier-bis Sechsjährige Kinder, 2nd ed.; Verlag Weinheim: Landsberg, Germany, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. ICF-CY International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health—Children + Youth Version; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Boyatzis, C.; Satyaprasad, C. Children’s facial and gestural decoding and encoding: Relations between skills and with popularity. J. Nonverbal Behav. 1994, 18, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randhawa, E. Das Frühkindliche Selbstkonzept. Struktur, Entwicklung, Korrelate und Einflußfaktoren. Dissertation 2012. Available online: https://opus.ph-heidelberg.de/frontdoor/index/docld/42/file/Randdhawa_Dissertation_Selbstkonzept (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Lloyd-Esenkaya, A.; Russell, J.; St Clair, M.C. What Are the Peer Interaction Strengths Difficulties in Children with Developmental Language Disorder? A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Resfr. Public Health 2020, 17, 3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J.; Garrett, Z.; Nye, C. Speech and language therapy interventions for children with primary speech and language delay or disorder. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2003, 3, CD004110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timm, A. Sprache und Interaktion im Kindergarten. Eine Quantitativ-Qualitative Analyse der Sprachlichen und Kommunikativen Kompetenzen von drei- bis Sechsjährigen Kindern; Julius Klinkhard: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Buzhardt, J.; Wallisch, A.; Irvin, D.; Boyd, B.; Salley, B.; Jia, F. Exploring Growth in Expressive Communication of Infants and Toddlers with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Early Interv. 2022, 44, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, J.J. Investing in disadvantaged young children is an economically efficient policy. In Building the Economic Case for Investments in Preschool; accessed 2015; Committee for Economic Development: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, A.L.; Chiat, S. Evaluation of speech and language therapy interventions for pre-school children with specific language impairment: A comparison of outcomes following specialist intensive, nursery-based and no intervention. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2009, 44, 616–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombes, L.; Bristowe, K.; Ellis-Smith, C.; Aworinde, J.; Fraser, L.K.; Downing, J.; Bluebond-Langener, M.; Chambers, L.; Murtagh, F.E.M.; Harding, R. Enhancing validity, reliability and participation in self-reported health outcome for children and young people: A systematic review of recall period, response scale format, and administration modality. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 1803–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka, J.; Kwon, J.; Petrou, S.; Lancsar, E.; Ratcliffe, J. Mind the (inter-rater) gap. An investigation of self-reported versus proxy-reported assessments in the derivation of childhood utility values for economic evaluation: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 240, 112543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortensen, J.A.; Barnet, M.A. Teacher-child interactions in Infant/toddler child care and socioemotional development. Early Educ. Dev. 2015, 26, 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehouse, A.J.O.; Varcin, K.J.; Pilar, S.; Billingham, W.; Alvares, G.A.; Barbaro, J.; Bent, C.A.; Blenkley, D.; Boutrus, M.; Chee, A.; et al. Effect of Preemptive Intervention on Developmental Outcomes Among Infants Showing Early Signs of Autism. A Randomized Clinical Trial of Outcomes to Diagnosis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, e213298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickinson, D.K.; Porche, M.V. Relation between language experiences in preschool classrooms and children’s kindergarten and fourth-grade language and reading abilities. Child Dev. 2011, 82, 870–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botting, N.; Conti-Ramsden, G. Social and Behavioural Difficulties in Children with Language Impairment. Child Lang. Teach. Ther. 2000, 16, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggio, V.; Grana, N.E.; Richaudeau, A.; Torres, S.; Giannotti, A.; Suburo, A.M. Behavior Problems in Children with Specific Language Impairment. J. Child Neurol. 2014, 29, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.J.; Beitchman, J.H.; Brownlie, E.B. Twenty-Year Follow-up of Children with and Without Speech-Language-Impairments: Family, Educational, Occupational, and Quality of Life Outcomes. Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 2010, 19, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Child | Age (y) *1 | Native Family Language | IQ (SON-R) *2 [26] | Number of Siblings | ICD-10 *3 [25] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | 6 | Polish | h | 1 | F80-9 |

| N | 5 | German | a | 1 | F80.9 |

| L | 5 | German | a | 1 | F80.9, F82.9 |

| P | 5 | Russian | a(b), borderline | 0 | F80.9 |

| K | 5 | German | a | 1 | F80.9 |

| D2 | 5 | Polish | a | 1 | F80.9, F82.9 |

| J1 | 5 | Russian | h | 9 | F80.9 |

| J2 | 5 | German | a | 1 | F80.9, F82.9 |

| E | 4 | Russian | a | 1 | F80.9 |

| Skills | Test Procedure | Validated |

|---|---|---|

| Language + Speech | SETK—3–5 Test for language/speech development of children 3–5 years [27] | yes |

| AWST-R—Vocabulary test for children 3–5 years [28] | yes | |

| PDSS—Patholinguistic diagnostics for speech-language-impaired children [29] | yes | |

| Cognition | Kaufmann Assessment Battery for Children II (KABC-II 2015) [30] | yes |

| SON-R2.5–7—Non-verbal IQ test for children 2.5–7 years [26] | yes | |

| Motor skills + Movement | MOT 4–6—Test for children 4–6 years [31] | yes |

| Child | Linguistic Skills Before Therapy | Linguistic Skills After Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| D1 | hardly any dialogue ability | partially good dialogue ability |

| N | hardly any dialogue ability | good dialogue ability |

| L | limited dialogue ability | good dialogue ability |

| P | good dialogue ability | good dialogue ability |

| K | good dialogue ability | good dialogue ability |

| D2 | limited dialogue ability | good dialogue ability |

| J1 | limited dialogue ability | good dialogue ability |

| J2 | limited dialogue ability | good dialogue ability |

| E | hardly any dialogue ability | good dialogue ability |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ullrich, D.; Marten, M. Development of Language and Pragmatic Communication Skills in Preschool Children with Developmental Language Disorder in a Speech Therapy Kindergarten—A Real-World Study. Children 2025, 12, 921. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070921

Ullrich D, Marten M. Development of Language and Pragmatic Communication Skills in Preschool Children with Developmental Language Disorder in a Speech Therapy Kindergarten—A Real-World Study. Children. 2025; 12(7):921. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070921

Chicago/Turabian StyleUllrich, Dieter, and Magret Marten. 2025. "Development of Language and Pragmatic Communication Skills in Preschool Children with Developmental Language Disorder in a Speech Therapy Kindergarten—A Real-World Study" Children 12, no. 7: 921. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070921

APA StyleUllrich, D., & Marten, M. (2025). Development of Language and Pragmatic Communication Skills in Preschool Children with Developmental Language Disorder in a Speech Therapy Kindergarten—A Real-World Study. Children, 12(7), 921. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070921