Simple Moisture Sensing Element Using Carbon Nanotube Composite Paper

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

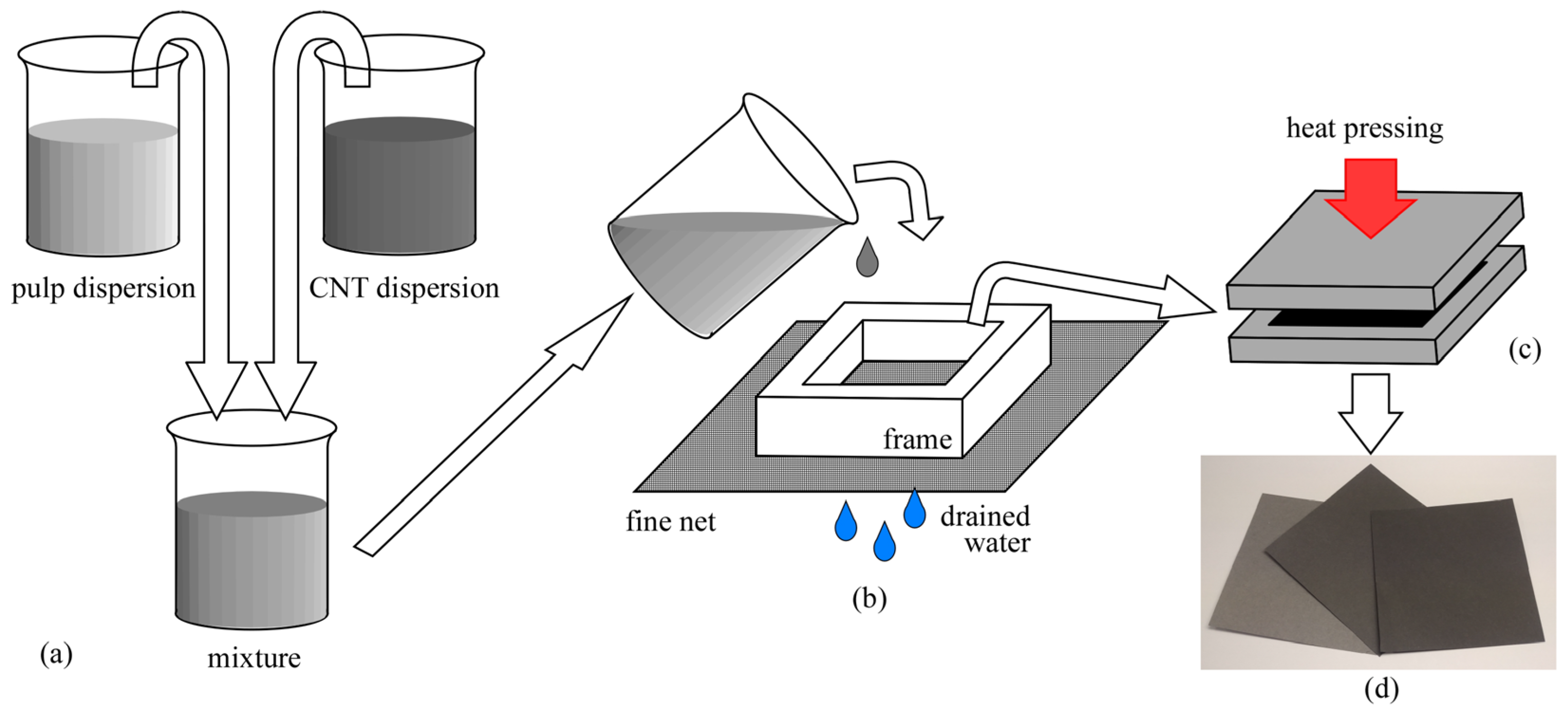

2.1. Carbon Nanotube Composite Paper Fabrication Method

2.2. Evaluation of Carbon Nanotube Composite Paper for Moisture Sensing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Resistivity of CNT Composite Paper

3.2. Evaluation of Changes in Volume and Resistivity of CNT Composite Paper with Moisture Absorption

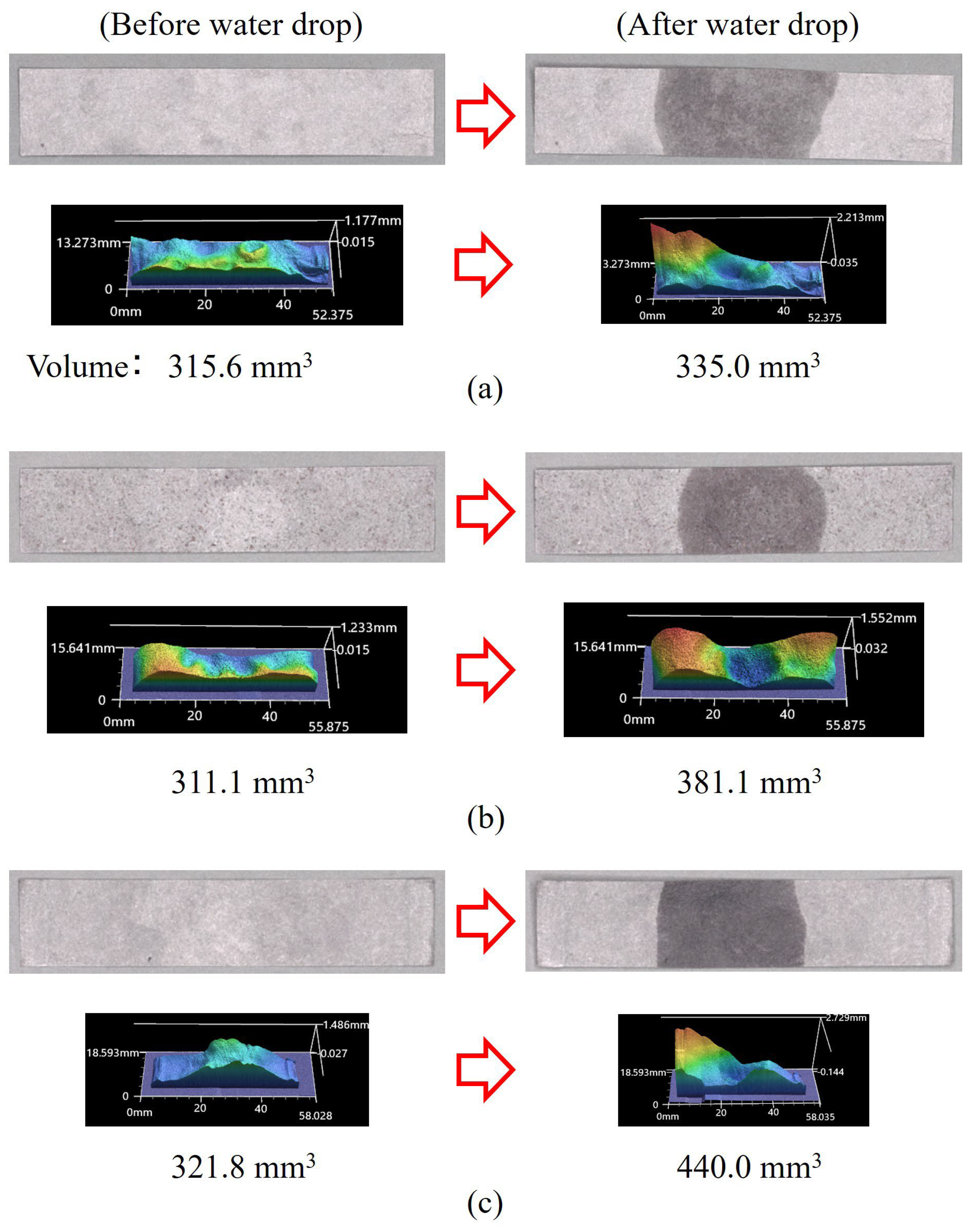

3.2.1. Evaluation of Relationship Between Volume and Resistance Changes

3.2.2. Real-Time Observation of Resistance Change to Water Droplet Absorption

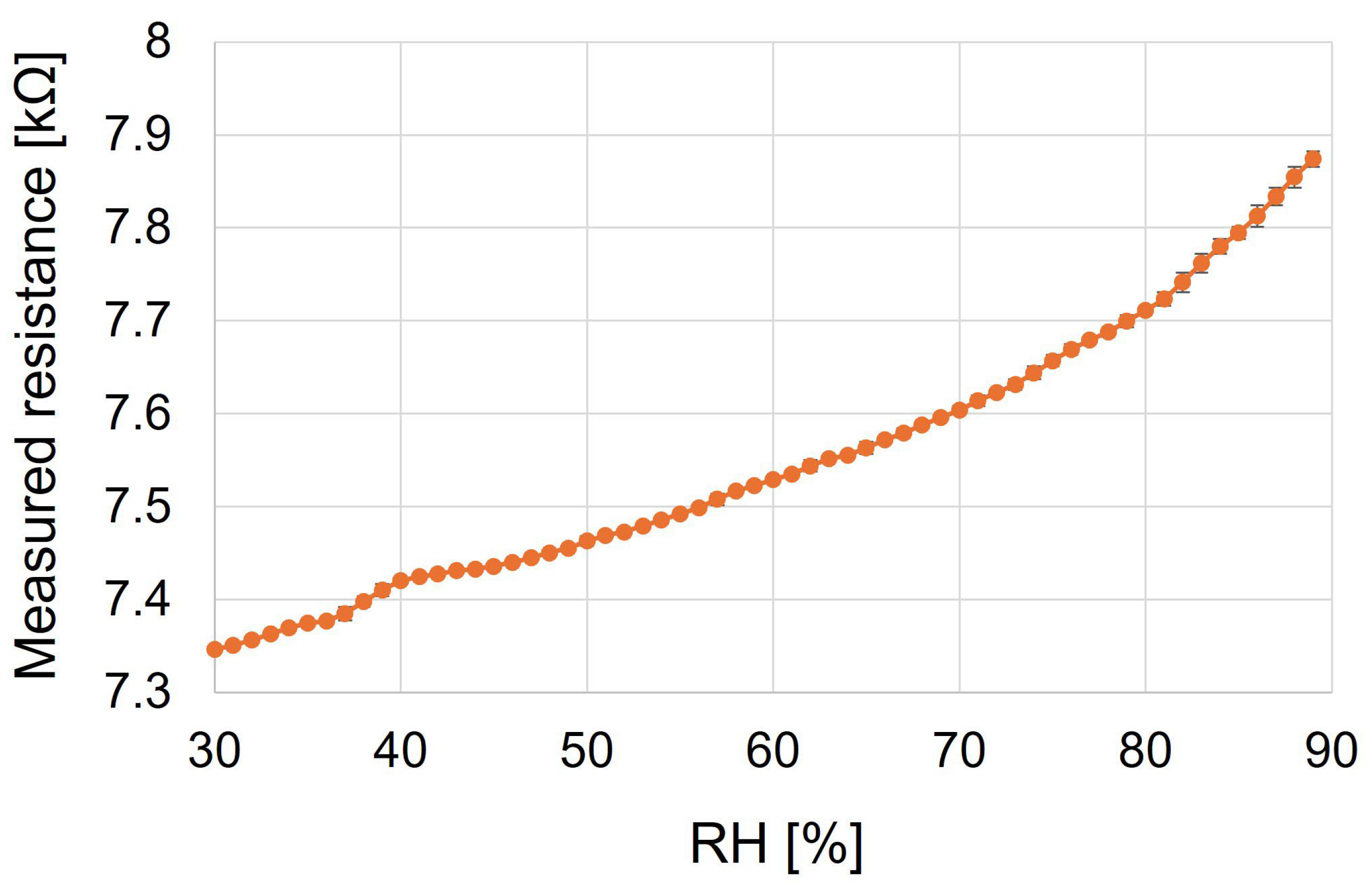

3.2.3. Evaluation of Resistance Change Regarding Humidity

3.3. Comparison with Other Studies on Moisture Sensing Elements

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| CNT | Carbon nanotube |

| SWCNT | Single-walled carbon nanotube |

| MWCNT | Multi-walled carbon nanotube |

| SDS | Sodium dodecyl sulfate |

| 3D | Three dimensional |

| 2D | Two dimensional |

| 1D | One dimensional |

References

- Hart, J.K.; Martinez, K. Environmental sensor networks: A revolution in the earth system science? Earth-Sci. Rev. 2006, 78, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, S.D.T.; Suryadevara, N.K.; Mukhopadhyay, S.C. Towards the implementation of IoT for environmental condition monitoring in homes. IEEE Sens. J. 2013, 13, 3846–3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Dou, M.; Chen, J.; Li, H. Natural disaster monitoring with wireless sensor networks: A case study of data-intensive applications upon low-cost scalable systems. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2013, 18, 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, L.; Briole, P.; Martin, O.; Thom, C.; Malet, J.-P.; Ulrich, P. Monitoring landslide displacements with the Geocube wireless network of low-cost GPS. Eng. Geol. 2015, 195, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ma, W.; Xu, L.; Chen, W.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, C.; Kotov, N.A. Nanoparticle-based environmental sensors. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2010, 70, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, A.; Rizwan, K.; Farooq, U.; Iqbal, S.; Iqbal, T.; Awwad, N.S.; Ibrahium, H.A. Polymer based nanocomposites: A strategic tool for detection of toxic pollutants in environmental matrices. Chemosphere 2022, 303, 134923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catarinucci, L.; de Donno, D.; Mainetti, L.; Palano, L.; Patrono, L.; Stefanizzi, M.L.; Tarricone, L. An IoT-aware architecture for smart healthcare systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2015, 2, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Kara, S. Methodology for monitoring manufacturing environment by using wireless sensor networks (WSN) and the Internet of Things (IoT). Procedia CIRP 2017, 61, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Andrews, B.; Lam, K.P.; Höynck, M.; Zhang, R.; Chiou, Y.-S.; Benitez, D. An information technology enabled sustainability test-bed (ITEST) for occupancy detection through an environmental sensing network. Energy Build. 2010, 42, 1038–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, A.; Ponce, P.; Mata, O.; Molina, A.; Meier, A. Local Weather Station Design and Development for Cost-Effective Environmental Monitoring and Real-Time Data Sharing. Sensors 2023, 23, 9060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulzer, M.; Christen, A.; Matzarakis, A. Predicting indoor air temperature and thermal comfort in occupational settings using weather forecasts, indoor sensors, and artificial neural networks. Build. Environ. 2023, 234, 110077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.; Schillereff, D.N.; Baas, A.C.; Chadwick, M.A.; Main, B.; Mulligan, M.; O’Shea, F.T.; Pearce, R.; Smith, T.E.; van Soesbergen, A.; et al. Low-cost electronic sensors for environmental research: Pitfalls and opportunities. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 2020, 45, 305–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahani, H.; Wagiran, R.; Hamidon, M.N. Humidity sensors principle, mechanism, and fabrication technologies: A comprehensive review. Sensors 2014, 14, 7881–7939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oya, T.; Ogino, T. Production of electrically conductive paper by adding carbon nanotubes. Carbon 2008, 46, 169–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iijima, S. Helical micro-tubules of graphitic carbon. Nature 1991, 354, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, V.N. Carbon nanotubes: Properties and application. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2004, 43, 61–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odom, T.W.; Huang, J.L.; Kim, P.; Lieber, C.M. Atomic structure and electronic properties of single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nature 1998, 391, 62–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbesen, T.W.; Lezec, H.J.; Hiura, H.; Bennett, J.W.; Ghaemi, H.F.; Thio, T. Electrical conductivity of individual carbon nanotubes. Nature 1996, 382, 54–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.F.; Files, B.S.; Arepalli, S.; Ruoff, R.S. Tensile loading of ropes of single wall carbon nanotubes and their mechanical properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 84, 5552–5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresselhaus, M.S.; Dresselhaus, G.; Avouris, P. (Eds.) Carbon Nanotubes: Synthesis, Structure, Properties, and Applications; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jorio, A.; Dresselhaus, M.S.; Dresselhaus, G. (Eds.) Carbon Nanotubes: Advanced Topics in the Synthesis, Structure, Properties, and Applications; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hata, K. Great expectations for a dream material, 21st century industrial revolution. AIST Stories 2013, 1, 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, A.K.-T.; Hui, D. The revolutionary creation of new advanced materials—Carbon nanotube composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2002, 33, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, R.; Bose, S. Carbon nanotube based composites—A review. J. Miner. Mater. Charact. Eng. 2005, 4, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, M.T.; Gun’ko, Y.K. Recent advances in research on carbon nanotube–polymer composites. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 1672–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esawi, A.M.K.; Farag, M.M. Carbon nanotube reinforced composites: Potential and current challenges. Mater. Des. 2007, 28, 2394–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, Y.; Oya, T. Unique dye-sensitized solar cell using carbon nanotube composite-papers with gel electrolyte. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamekawa, Y.; Arai, K.; Oya, T. Development of transpiration-type thermoelectric power generating material using carbon-nanotube-composite papers with capillary action and heat of vaporization. Energies 2023, 16, 8032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyama, A.; Oya, T. Improved performance of thermoelectric power generating paper based on carbon nanotube composite papers. Carbon Trends 2022, 7, 100149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okochi, K.; Oya, T. Unique triboelectric nanogenerator using carbon nanotube composite papers. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyomasu, R.; Oya, T. Development and Improvement of a “Paper Actuator” Based on Carbon Nanotube Composite Paper with Unique Structures. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhas; Gupta, V.K.; Carrott, P.J.M.; Singh, R.; Chaudhary, M.; Kushwaha, S. Cellulose: A review as natural, modified and activated carbon adsorbent. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 216, 1066–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, S.E.; Newsome, P.T. The sorption of water by cellulose. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1934, 26, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etale, A.; Onyianta, A.J.; Turner, S.R.; Eichhorn, S.J. Cellulose: A review of water interactions, applications in composites, and water treatment. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 2016–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chami Khazraji, A.; Robert, S. Interaction effects between cellulose and water in nanocrystalline and amorphous regions: A novel approach using molecular modeling. J. Nanomater. 2013, 2013, 409676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morehead, F.F. A method for studying the effect of humidity on the cross-sectional swelling of some common fibers. Text. Res. J. 1952, 22, 535–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, V.; Savagatrup, S.; He, M.; Lin, S.; Swager, T.M. Carbon nanotube chemical sensors. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 599–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, T.C.; Ramakrishna, S. A conceptual review of nanosensors. Z. Fuer Naturforschung A Phys. Sci. 2006, 61, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Carbon-nanotube based electrochemical biosensors: A review. Electroanalysis 2005, 17, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauter, M.S.; Elimelech, M. Environmental applications of carbon-based nanomaterials. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 5843–5859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-P.; Zhao, Z.-G.; Liu, X.-W.; Zhang, Z.-X.; Suo, C.-G. A Capacitive Humidity Sensor Based on Multi-Wall Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs). Sensors 2009, 9, 7431–7444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Maddipatla, D.; Bose, A.K.; Hajian, S.; Narakathu, B.B.; Williams, J.D.; Mitchell, M.F.; Atashbar, M.Z. Printed carbon nanotubes-based flexible resistive humidity sensor. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 12592–12601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.L.; Hu, C.G.; Fang, L.; Wang, S.X.; Tian, Y.S.; Pan, C.Y. Humidity sensor based on multi-walled carbon nanotube thin films. J. Nanomater. 2011, 2011, 707303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Liu, Y.; Fang, Z.; Kuang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, C.; Chen, G. Flexible and highly sensitive humidity sensor based on cellulose nanofibers and carbon nanotube composite film. Langmuir 2019, 35, 4834–4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeow, J.T.W.; She, J.P.M. Carbon nanotube-enhanced capillary condensation for a capacitive humidity sensor. Nanotechnology 2006, 17, 5441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.-W.; Kim, B.; Li, J.; Meyyappan, M. Carbon nanotube based humidity sensor on cellulose paper. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 22094–22097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapperton, R.H. (Ed.) The Paper-making Machine: Its Invention, Evolution, and Development; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.; Yuan, Z.; Duan, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Tai, H. An ingenious strategy for improving humidity sensing properties of multi-walled carbon nanotubes via poly-L-lysine modification. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 289, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Liu, J.; Deng, Y.; Gao, S.; Mäder, E. Cellulose fibres with carbon nanotube networks for water sensing. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 5541–5547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Mäder, E.; Liu, J. Unique water sensors based on carbon nanotube–cellulose composites. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2013, 185, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Hou, Z.; Wu, K.; Zhao, H.; Liu, S.; Fei, T.; Zhang, T. Flexible humidity sensor based on modified cellulose paper. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 339, 129879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Li, X.; Kasuga, T.; Uetani, K.; Nogi, M.; Koga, H. All-cellulose-derived humidity sensor prepared via direct laser writing of conductive and moisture-stable electrodes on TEMPO-oxidized cellulose paper. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 3712–3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Wei, Y.; Kuang, Y.; Qian, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, F.; Chen, G. Porous and conductive cellulose nanofiber/carbon nanotube foam as a humidity sensor with high sensitivity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 292, 119684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Yan, M.; Wang, S.; Yuan, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Sun, P.; Xie, G.; Du, X.; Tai, H. Facile, flexible, cost-saving, and environment-friendly paper-based humidity sensor for multifunctional applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 21840–21849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Lei, Y.; Li, X.; Cheng, C.; Yang, L.; Jiao, L.; Yang, S.; Shu, D.; Cheng, B. Highly sensitivity and wide-range flexible humidity sensor based on LiCl/cellulose nanofiber membrane by one-step electrospinning. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 503, 158018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.; Wang, Z.; Xue, Y.; Yan, J.; Dutta, A.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Du, S.; Guo, L.; et al. Pencil-on-paper humidity sensor treated with NaCl solution for health monitoring and skin characterization. Nano Lett. 2023, 23, 1252–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Huang, J.; Guo, Z. Functionalized paper with intelligent response to humidity. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 633, 127844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachibana, S.; Wang, Y.-F.; Sekine, T.; Takeda, Y.; Hong, J.; Yoshida, A.; Abe, M.; Miura, R.; Watanabe, Y.; Kumaki, D.; et al. A printed flexible humidity sensor with high sensitivity and fast response using a cellulose nanofiber/carbon black composite. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 5721–5728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arman Kuzubasoglu, B. Recent studies on the humidity sensor: A mini review. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2022, 4, 4797–4807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielli, V.; Frasconi, M. Cellulose-based functional materials for sensing. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, T.; Liu, K.; Zhu, L.; Miao, C.; Chen, T.; Gao, M.; Wang, J.; Si, C. Modulation and mechanisms of cellulose-based hydrogels for flexible sensors. SusMat. 2025, 5, e255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodoro, K.B.R.; Sanfelice, R.C.; Migliorini, F.L.; Pavinatto, A.; Facure, M.H.M.; Correa, D.S. A review on the role and performance of cellulose nanomaterials in sensors. ACS Sens. 2021, 6, 2473–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CNT | Quantity [mg] | Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| SG101 | 0.5 | ZEON CORPORATION, Tokyo, Japan |

| (6,5)-chirality (SG65i) | 2.0 | CHASM, Boston, MA, USA |

| NC7000 | 1.0 | Nanocyl SA, Sambreville, Belgium |

| Contained CNT | Sheet Resistance [kΩ/sq.] | Thickness [mm] (Averaged) |

|---|---|---|

| SG101 | 1.40 | 0.092 |

| (6,5)-chirality | 0.64 | 0.119 |

| NC7000 | 1.58 | 0.100 |

| Contained CNT | Resistance [kΩ] (After Water Drop) | Rate of Resistance Change [%] | Rate of Volume Change [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| SG101 | 10.02 | 43.6 | 6.1 |

| (6,5)-chirality | 8.15 | 155.5 | 22.5 |

| NC7000 | 16.84 | 112.6 | 36.7 |

| Structure | Materials | Method of Fabrication | Ease of Fabrication | Target | Sensing Range | Response/ Recovery Time | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiber (1D) | MWCNT /Cellulose | Dip coating | Good | Water (Immersion) | – (When immersed) | N/A | [49] |

| Film (2D) | MWCNT /Cellulose | Drying gel 1 | Fair | Water (Immersion) | – (When immersed) | N/A | [50] |

| Sheet (2D) | COOH-functionalized SWCNT /Cellulose paper | Drop-cast coating | Fair | Humidity | 10% to 95% RH | 6 s/120 s | [46] |

| Sheet (2D) | EPTAC 2/ Cellulose paper/ Silver | Immersion/ Screen printing | Fair | Humidity | 11% to 95% RH | 35 s/180 s | [51] |

| Sheet (2D) | Printing (cellulose) paper/ Polyester conductive tape | Tape-attach | Good | Humidity | 41.1% to 91.5% RH | 472 s/19 s | [54] |

| Sheet (2D) | LiCl/ Cellulose nanofiber | Electrospinning | Fair | Humidity | 5% to 98% RH | 99 s/110 s | [55] |

| Sheet (2D) | Printing (cellulose) paper/NaCl | Soaking | Good | Humidity | 6% to 90% RH | 1208 s/537 s | [56] |

| Sheet (2D) | Printing (cellulose) paper/ Nitrocellulose/ MWCNT | Coating | Good | Humidity (Water is acceptable) | 54% to 75% RH | 500 to 1000 s/ N/A | [57] |

| Film (2D) | MWCNT /Cellulose nanofiber/ Silver paste | Stencil printing/ Annealing | Fair | Humidity | 30% to 90% RH | 10 s/6 s | [58] |

| Film (2D) | Cellulose nanofiber | Vacuum filtration/Processing with CO2 laser | Fair | Humidity | 11% to 98% RH | 60 s/495 s | [52] |

| Foam (3D) | Cellulose nanofiber/ MWCNT | Freeze drying | Fair | Humidity | 11% to 95% RH | 322 s/442 s | [53] |

| Sheet (3D 3) | CNT 4 /Cellulose paper | Papermaking | Good | Both humidity and water droplet | 23% to 89% RH 5 < 10 μL 6 | 160 s/60 s 7 | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oya, T.; Saito, T.; Morita, Y.; Arai, K. Simple Moisture Sensing Element Using Carbon Nanotube Composite Paper. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 373. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors13100373

Oya T, Saito T, Morita Y, Arai K. Simple Moisture Sensing Element Using Carbon Nanotube Composite Paper. Chemosensors. 2025; 13(10):373. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors13100373

Chicago/Turabian StyleOya, Takahide, Tadashi Saito, Yuma Morita, and Koya Arai. 2025. "Simple Moisture Sensing Element Using Carbon Nanotube Composite Paper" Chemosensors 13, no. 10: 373. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors13100373

APA StyleOya, T., Saito, T., Morita, Y., & Arai, K. (2025). Simple Moisture Sensing Element Using Carbon Nanotube Composite Paper. Chemosensors, 13(10), 373. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors13100373