1. Introduction

Due to the highly concentrated energy, flows induced by a dam break exhibit extreme violence, characterized by significant deformation of the free surface and non-linearity. This can lead to severe floods and structural damage as it propagates along rivers and channels. Researchers such as Chanson et al. [

1] and Liao et al. [

2] have extensively studied the dam break problem theoretically, experimentally, and numerically. Furthermore, Janosi et al. investigated the behavior of soil beds affected by the flows induced by dam breaks [

3,

4,

5]. In the study by Pstacchini et al. [

5], sediment transport due to dam break swash uprush was outlined numerically, including investigating the collision of the collapsed water column with the soil bed in inclined tanks both experimentally and numerically. Brocchini and Peregrine [

4,

6,

7] examined the dynamics of strong turbulence at the free surface and wave profiles using experimental and theoretical methods. Despite numerous efforts to analyze it, the complexity and non-linearity of the dam break problem pose challenges that cannot be easily solved, especially when flows interact with structures or movable soil beds. Therefore, accurate analysis is crucial for estimating consequences and preparing countermeasures.

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) has become a powerful tool for simulating complex flow behaviors, particularly those involving large free surface deformations such as dam break problems. Traditionally, CFD methods have relied on Eulerian approaches, wherein computational grids or meshes are employed to track fluid motion and solve governing equations for velocity and pressure distribution. Recent reviews highlight continuing improvements to VOF interface reconstruction and curvature evaluation methods, as well as hybrid strategies coupling VOF with other interface-capturing approaches to reduce numerical diffusion and improve interface fidelity [

8,

9]. Hybrid particle–mesh methods have been revisited in recent years, offering efficient ways to combine Lagrangian particle advantages with grid-based solvers for pressure/viscous terms [

10]. Despite these advancements, conventional grid-based CFD methods face inherent limitations in accurately capturing highly dynamic phenomena characterized by large deformations, fragmentation, and coalescence [

11,

12]. Moreover, numerical diffusion arising from the advection term in the governing equations often leads to discrepancies between simulated and physical results [

13,

14]. Juez et al. [

13,

14] have explored the impact of transient flows on heterogeneous erodible beds using the Hirano model and the Exner equation, providing critical insights into two-dimensional morphodynamics. These investigations have expanded the understanding of sediment transport and bed evolution under transient conditions, emphasizing the need for more accurate computational methods. Meanwhile, studies by Amicarelli et al. [

15] and Albano et al. [

16] have applied particle-based methods, such as Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH), to analyze large floating body transport in flash floods and free surface flows, highlighting the growing adoption of Lagrangian approaches in fluid dynamics [

17].

The particle method represents a fully Lagrangian approach to CFD, offering a fundamentally different framework from traditional Eulerian methods. Instead of relying on computational grids, the particle method models fluid and solid materials as discrete particles that carry individual physical properties, including position, velocity, acceleration, and pressure. This particle-based representation allows for a natural handling of highly nonlinear phenomena such as large free surface disturbances, sharp interfaces, and complex fragmentation events. Furthermore, a key advantage of the particle method lies in its ability to circumvent numerical diffusion issues associated with the advection term in the Navier–Stokes equations. Among the various particle-based approaches, the SPH and Moving Particle Semi-implicit (MPS) methods are widely recognized for their effectiveness in fluid simulations. SPH, first introduced by Monaghan, approximates pressure using an equation of state, leading to relatively fast computation times [

18]. Hybrid particle–mesh methods have been revisited in recent years, offering efficient ways to combine Lagrangian particle advantages with grid-based solvers for pressure/viscous terms [

19,

20]. In contrast, the MPS method, originally developed by Koshizuka et al., determines pressure through the Poisson Pressure Equation (PPE), which suppresses pressure fluctuations and enhances accuracy at the cost of increased computational expense [

21,

22]. Comparative studies have indicated that MPS exhibits superior performance in capturing sharp interfaces and highly deformed free surface structures, making it a particularly promising candidate for simulating complex hydrodynamic problems, including those involving Fluid-Solid Interaction (FSI) [

23,

24].

Recent developments in the MPS method have focused on refining its accuracy and stability for a broader range of FSI problems. Tanaka and Masunaga [

25] introduced a multi-source term modification to the PPE formulation, effectively reducing pressure fluctuations and improving numerical robustness. Similarly, Lee et al. [

12] proposed a relaxation parameter to optimize the computation of pressure fields, enhancing the method’s overall stability. Further advancements have been made in modeling multi-phase flows, where Nomura et al. [

26] and Shirakawa et al. [

27] investigated surface tension and buoyancy effects, while Kim et al. [

28] introduced a more physically consistent surface tension model for improved interfacial dynamics. These enhancements underscore the continuous evolution of the MPS method as a viable alternative to traditional CFD approaches, especially for hydrodynamics and sediment transport studies [

29]. Given its ability to handle large deformations and complex interactions, MPS presents a compelling approach for advancing numerical simulations of granular beds, where highly non-linear solid–solid interactions govern the bed mechanics, similar to problems addressed by the Discrete Element Method (DEM) [

30,

31].

In a previous study by Kim et al. [

29], the swash uprush problem was investigated with a particle method where a PEO solution was modeled as soil. At that time, the corresponding experiment applied PEO solution for soil, thus the MPS with fluid with large viscosity was implemented, while the numerical results showed reasonable agreement with overall tendencies, this fluid-based approach may become inadequate when addressing the strongly nonlinear mechanics of granular solid particles, where frictional and collisional forces dominate. To extend the MPS method to robust solid particle simulation, physics-based solid particle models were subsequently developed [

32], and their validity was confirmed through comparisons with corresponding experimental measurements, including the angle of repose.

This study aims to further extend the applicability of the MPS method for simulating coupled fluid-solid particle interactions in dam-break-induced flows over granular beds. A novel friction model for solid particles and an improved interaction model between fluid and solid particles have been incorporated to enhance the accuracy of the method. All terms proposed for the fluid-solid interaction MPS method are validated through comparison to corresponding experiments and theoretical values. Furthermore, the validated MPS model is employed to simulate large waves generated by dam breaks over mobile beds, analyzing the energy transferring and the mitigation effects of sediment mobility compared to fixed-bed conditions. Additionally, simulations of step-down discontinuous seabed configurations are conducted to evaluate the impact of mobile bed dynamics. The outcomes of this study contribute to the improvement of numerical simulation methods for highly dynamic fluid-solid interactions, with potential applications in dam failure analysis, coastal engineering, and sediment transport prediction.

3. Simulation Results

This section presents the results of numerical simulations based on four distinct bed configurations, as schematically illustrated in

Figure 2. The methodology employed utilizes the MPS method with rigorous validation of the solid particle interaction terms established in [

32]. The simulation setup is designed to benchmark the solid model’s applicability to particle-fluid interaction problems against the established experimental reference data from [

33].

The computational domain is defined as a two-dimensional rectangular region (), partitioned by a gate at . Both the upstream and downstream regions are initialized with a mobile sediment bed, serving as a dynamic boundary condition. The initial parameters, specifically the water column height and sediment layer thickness, are varied according to the specific case configurations.

To systematically investigate the influence of step discontinuities on the coupled flow and sediment dynamics, four distinct bed geometries are analyzed (

Figure 2):

Case a: Horizontal bed (reference case)

Case b: Sudden upstep (5 cm)

Case c: Sudden downstep (10 cm)

Case d: Submerged downstep (10 cm)

The numerical investigation focuses on capturing the hydrodynamic response and the resultant morphological evolution of the bed following the sudden release of the dam-break flow. The variation in geometry provides critical insight into the influence of discontinuous boundaries on wave propagation, sediment transport mechanisms, and the stability of the numerical solution.

The numerical parameters were meticulously selected based on the convergence study detailed in [

12]. The initial particle distance was set to

m, ensuring sufficient spatial resolution, with a corresponding explicit time interval of

s. satisfy the Courant-Friedrichs-Lewy (CFL) condition. The material properties used are 1000 kg/m

3 for water particle and 1580 kg/m

3 for solid particle. The kinematic viscosity of water was 1.0

ms and the inter-particle friction coefficient for the solid phase was 0.35.

3.1. Case a: Horizontal Bed

Figure 3 presents a comparison of snapshots between experiment and numerical simulation over a horizontal flat bed, with 0.35 m of water in the upstream reservoir. For the simulation model, total 1,210,000 particles, which includes 51,000 water particles, 70,000 solid particles and dummy and wall particles, were used. The referenced experiment was carried out from [

33].

The initial stages of the dam-break flow are characterized by a smooth propagation over the dry sediment layer.

Figure 3 provides a visual comparison between the numerical prediction and the physical reference data. The numerical model successfully reproduces key morphological features, notably the formation of a sand dune approximately

downstream from the gate location, triggered by the collapse of the water column. The subsequent interaction involves wave run-up and localized sediment layer erosion, consistent with the observed physical phenomena.

A critical aspect of the mobile bed model is its representation of energy dissipation.

Figure 4 compares the wave propagation front for the mobile and fixed bed conditions. The observable spatial lag in the mobile bed case demonstrates the substantial energy sink provided by the sediment mobilization process. The kinetic energy transfer from the fluid to the solid phase effectively reduces the wave propagation speed compared to the fixed bed, where energy dissipation is limited to viscous effects and boundary friction.

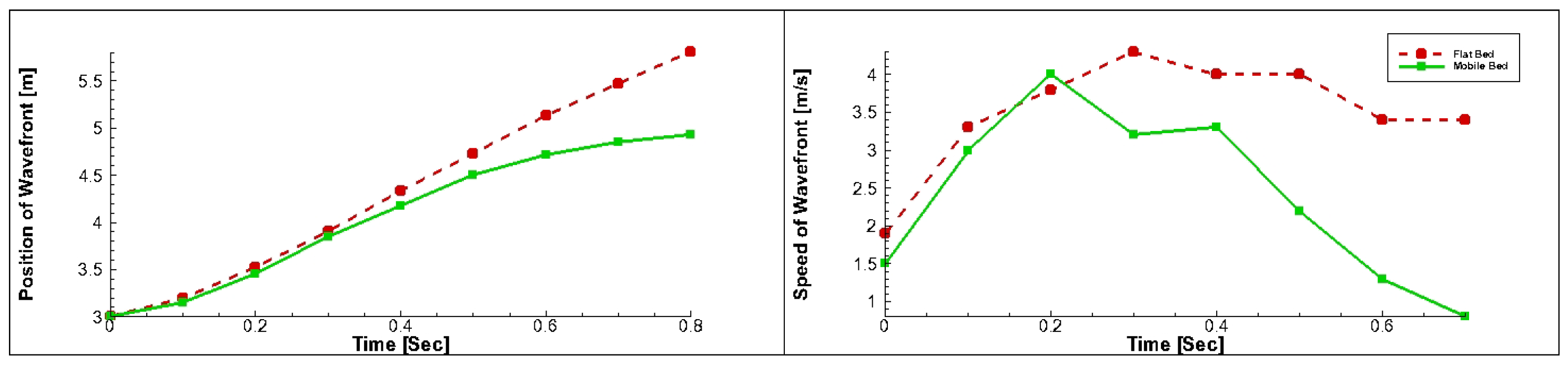

To compare this quantitatively, the wave head position and celerity comparison are shown in

Figure 5. The figure plots the position and velocity of the wave head over time for both bed conditions. As shown in

Figure 5 (right), the celerity under the mobile bed decreased dramatically after

, while the fixed bed maintained a higher speed. This quantitative analysis corroborates the observation from

Figure 4, confirming that the sediment transport mechanism acts as a major energy sink.

The primary reason for this restriction is that the leading edge of the wave propagating over the fixed bed reaches the right wall of the computational domain around

. Following this impact, the subsequent wave reflection from the rigid boundary contaminates the fluid dynamics near the wave front. Since the objective of

Figure 5 is to compare the fundamental energy dissipation mechanisms between the mobile and fixed bed systems in an unperturbed flow regime, extending the analysis beyond the initial wall reflection time would lead to physically inaccurate and misleading conclusions regarding the characteristic wave speed.

The quantitative assessment of the proposed mobile bed model is illustrated by the sediment height profile comparison, conducted by aligning the computational domain and sampling at uniformly distributed x-coordinates. As shown in the figure, the computational results accurately capture the experimental sediment morphology, including the formation and slope of the sand dune. This high degree of agreement is quantitatively confirmed by a low Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of at , effectively validating the accuracy and predictive capability of the numerical model.

The successful prediction is rooted in the model’s accurate representation of the energy dissipation mechanisms. In the case of the fixed bed, the energy is dissipated solely through viscous effects and friction from the wall boundary. Conversely, the mobile bed system exhibits significantly higher energy loss because the wave actively causes morphological perturbation of the sediment layer. Here, the kinetic energy of fluid particles is actively transferred to solid particles to mobilize them. Critically, the inter-particle friction force between solid particles is substantially higher than the fluid’s viscous force, contributing significantly to the total energy loss. Furthermore, the formation of a sediment dune converts the fluid’s kinetic energy into the potential energy of the solid bed. Unlike a fluid wave, the solid particles retain the deformed shape, meaning this converted potential energy remains in the system as a non-recoverable loss, resulting in the observed greater overall energy dissipation in the mobile bed system.

3.2. Case b: Bed with Sudden Upstep

In Case b (

Figure 2b), the

sudden upstep acts as a physical barrier, significantly altering the flow and sediment transport compared to the horizontal bed in Case a. When the gate opened, the gravitational force spontaneously initiated the collapse of the water column, generating and propagating a large wave. The simulation model for this case utilized a total of 1,260,000 particles, comprising 51,000 water particles, 75,000 solid particles, and dummy/wall particles. pon encountering the step (

), the flow underwent a partial reflection and was diverted upward, which subsequently led to increased turbulence and wave generation, visible as surface irregularities between

and

shown in

Figure 6. The upstep consumes a portion of the flow’s kinetic energy in in

Figure 7, converting it into potential energy and turbulence, thereby resulting in a potentially slower overall wave front propagation compared to Case a.

The sediment behavior is also distinctly modified by the geometry. The step likely causes local flow deceleration upstream, which could momentarily mitigate erosion or even induce a small localized deposition mound just before the step. Sediment transport over the step is complicated by the localized increase in shear stress as the flow accelerates up the face of the discontinuity. Furthermore, compared to Case a, the sudden upstep generated a large sand dune and induced a subsequent second impact further downstream. For quantitative validation, the profile comparison, conducted by aligning the computational domain and sampling at uniformly distributed x-coordinates, yielded a Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of at , demonstrating a high degree of agreement between the numerical results and the reference data.

3.3. Case c: Bed with Sudden Downstep

The

downstep configuration (

Figure 2c) creates a flow environment conducive to complex flow separation and high-energy impact. When the gate opens, the flow generated by the collapsed water column accelerates as it drops over the step, likely reaching a supercritical flow regime (

) before impingement onto the lower bed. Due to the high momentum and weight of the impinging water column, the simulation showed the physical crumbling of the solid step edge, beneath the water column. The resulting collapsed solid material then generates an inclined, slope-shaped bed. Propagating along this newly formed bed, the initial impact of the water jet with the lower sediment bed, observed between

and

, caused significant splashing and substantial energy dissipation as shown in

Figure 8.

The transferred energy from the fluid to the solid particles causes localized scour at the impact zone. The sediment material eroded from this depression is then transported and re-deposited further downstream, often forming a large dune. The water surface profile immediately downstream is characterized by high velocity and thin flow depth. Crucially, the flow often transitions to a submerged hydraulic jump-like feature beyond the impact zone, converting remaining kinetic energy into flow depth and further dissipating turbulent energy in

Figure 9. The successful capture of the step crumbling and subsequent large scour confirms the capability of the MPS model’s solid-fluid and solid–solid interaction models under extreme dynamic loading.

The profile comparison, conducted by aligning the computational domain and sampling at uniformly distributed x-coordinates, yielded a Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of at , demonstrating a high degree of agreement.

3.4. Case d: Bed with Submerged Downstep

Case d (

Figure 2d) introduces a submerged downstep condition, fundamentally altering the hydraulic mechanism from the free-fall scenario in Case c. In this setup, the wave front interacts with the tailwater depth, mitigating high-energy impact with turbulent mixing and localized sediment transport.

The capability of the MPS method to accurately capture the submerged flow behavior is demonstrated by comparing the simulation results with experimental snapshots in

Figure 10. The wave front, generated by the collapsing water column, accelerates over the step but forms a smooth, submerged flow as it enters the lower basin. A key feature observed in both the experiment and the simulation is the development of a highly turbulent mixing zone at the wave front, particularly between

and

. This turbulence is characteristic of a submerged hydraulic jump, where the accelerated flow transitioning from the step encounters the quiescent tailwater. The free surface profile was stabilized gradually after

.

The flow subsequent to the wave front led to the transport and re-deposition of the eroded sediment further downstream, resulting in the formation of a distinct dune structure. Both the experimental and numerical results confirm the formation of a localized scour hole immediately downstream of the step edge, which is driven by the intense shear stress generated at the base of the submerged flow. Comparison with the corresponding experiment demonstrates the high accuracy of the MPS method in predicting both the maximum scour depth and the location of maximum deposition.

To quantify the energy dissipation attributed to sediment mobility, the results from the mobile bed and fixed bed simulations for Case d are compared in

Figure 11.

In this comparison, several hydrodynamic differences were observed. Similar to Case a, the wave front celerity in the mobile bed condition is noticeably reduced compared to the fixed bed, confirming that sediment mobilization acts as an effective energy damping mechanism. This damping effect is also observable in the turbulent structure of the flow: in the fixed bed scenario, the entire energy loss from the hydraulic jump is converted into Turbulent Kinetic Energy (TKE) and wall friction. Conversely, in the mobile bed, the physical presence of sediment particles effectively damps the TKE generation by absorbing the fluid’s kinetic energy through particle motion and subsequent inter-particle friction, resulting in a fundamentally different energy partitioning structure.

Moreover, the point of view about the scour and energy partitioning was compared. The scour mechanism is modified from high-impact jet erosion (Case c) to erosion driven by high-velocity shear flow and bed recirculation (vortices) beneath the submerged jump. The water depth restricts the depth of scour but increases the lateral spread of the eroded material due to the enhanced turbulence in the submerged flow. This intense shear stress is immediately used to mobilize the sediment bed, leading to localized scour starting at the step transition. This mechanism fundamentally transforms the fluid’s kinetic energy into multiple components: (1) Sediment Kinetic Energy (the energy required to move the particles); (2) Non-recoverable Potential Energy (energy stored in the permanent deformation of the bed, such as the scour hole and dune); and (3) Inter-particle Friction (energy dissipated as heat due to friction between sediment particles, which is significantly higher than fluid viscosity). Due to the effective partitioning of kinetic energy into these additional sediment-related mechanisms, the mobile bed exhibits a greater overall system energy dissipation rate. This explains why the flow stabilizes faster and the free surface splash is less pronounced when compared to the fixed bed scenario (

,

Figure 11).

The profile comparison, conducted by aligning the computational domain and sampling at uniformly distributed x-coordinates, yielded a Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of at , demonstrating a high degree of agreement.

3.5. Comparative Discussion of Sediment Mobilization

The comparison across the four cases clearly highlights the dominant role of bed geometry in controlling flow energy transfer and subsequent sediment mobility, see

Table 1. The presence of the upstep in Case b induces a mitigating effect on sediment mobility. The step physically impedes flow propagation, resulting in a partial conversion of the flow’s kinetic energy into potential energy and a temporary reduction in flow velocity. This mechanism leads to the mitigation of sediment erosion and transport, offering valuable insight for designing structures aimed at reducing the damage caused by dam-break flow. In contrast, the downstep in Case c leads to the amplification of sediment mobility in localized areas. The impact of the flow plunging onto the downstream bed generates substantial turbulent energy and a high concentration of shear stress. This dynamic is expected to cause a large scour vortex immediately downstream of the discontinuity, a phenomenon that requires quantitative analysis to confirm the degree of sediment transport amplification.

For this quantitative assessment, Case c exhibited the RMSE among the four cases. This elevated error is attributed to the inherent difficulty in accurately capturing the strong impact shock waves and highly turbulent flow generated by the abrupt free-fall of the fluid. Nevertheless, with an RMSE of only 0.8%, this low error margin strongly suggests that the MPS method successfully achieved high fidelity and accuracy in modeling complex fluid-solid coupled problems.

The flow in Case d, unlike the dry-bed condition in Case c, features a stationary water body downstream, creating the effect of submerged conditions. This tailwater causes the shockwave to propagate submerged, leading to the formation of a hydraulic jump or a complex wave system. These submerged conditions increase the drag force acting on the wave front, consequently reducing its propagation velocity. The submerged propagation results in the formation of turbulent vortices, thereby altering the mechanism of energy transfer within the flow. Crucially, the sediment particles in this case experience significantly more complex fluid-solid interactions than those in the dry-bed scenario (Case c), making Case d a vital condition for verifying the numerical model’s capability to accurately reproduce the complex physical interpretation of coupled dynamics.

In the comparison between mobile and fixed beds for Case d, several hydrodynamic differences were observed. Similar to Case a, the wave front celerity in the mobile bed condition is noticeably reduced compared to the fixed bed, confirming that sediment mobilization acts as an effective energy damping mechanism. This damping effect is also observable in the turbulent structure of the flow: in the fixed bed scenario, the entire energy loss from the hydraulic jump is converted into Turbulent Kinetic Energy (TKE) and wall friction. Conversely, in the mobile bed, the physical presence of sediment particles effectively damps TKE generation by absorbing the fluid’s kinetic energy through particle motion and subsequent inter-particle friction, resulting in a fundamentally different energy partitioning structure.

Moreover, the perspective on scour and energy partitioning was compared. The scour mechanism is modified from high-impact jet erosion (Case c) to erosion driven by high-velocity shear flow and bed recirculation (vortices) beneath the submerged jump. The water depth restricts the depth of scour but increases the lateral spread of the eroded material due to the enhanced turbulence. This intense shear stress immediately mobilizes the sediment bed, leading to localized scour starting at the step transition. This mechanism fundamentally transforms the fluid’s kinetic energy into multiple components: (1) Sediment Kinetic Energy (the energy required to move the particles); (2) Non-recoverable Potential Energy (energy stored in the permanent deformation of the bed, such as the scour hole and dune); and (3) Inter-particle Friction (energy dissipated as heat due to friction between sediment particles). Due to the effective partitioning of kinetic energy into these additional sediment-related mechanisms, the mobile bed exhibits a greater overall system energy dissipation rate. This explains why the flow stabilizes faster and the free surface splash is less pronounced when compared to the fixed bed scenario (

,

Figure 11).

Although the results demonstrate good agreement with experiments, several limitations remain. The current simulation employs a fixed friction coefficient and uniform sediment particle size, which may restrict generalizability for natural environments. Computational cost also increases significantly due to the Poisson Pressure Equation, limiting long-duration simulations. Future work will address parameter variability and adaptive resolution to enhance model robustness.

4. Concluding Remarks

This study applied an enhanced Moving Particle Semi-implicit (MPS) method incorporating a solid particle formulation and frictional interaction model to simulate dam-break flows over four erodible bed configurations: a horizontal bed (Case a), sudden upstep (Case b), sudden downstep (Case c), and submerged downstep (Case d).

- 1.

Bed Evolution and Scour Profile: The model successfully captured the formation of scour holes, dune development, and the location of maximum deposition. In particular, the simulation reproduced the collapse of the downstep boundary and the formation of a smooth slope-shaped bed in Case c, indicating that the enhanced MPS framework can represent solid–solid and fluid–solid interactions under rapidly varying flow conditions.

- 2.

Wave Propagation Celerity: Comparisons between fixed and mobile bed conditions revealed a significant reduction in wave celerity when sediment was allowed to move. For instance, in Case a, the wave front velocity decreased markedly after 0.2 s under mobile bed conditions. Similar damping behavior was observed in Case d. These results confirm that sediment mobility plays a critical role in energy attenuation during dam-break events.

- 3.

Hydrodynamic Features: The MPS method reproduced the dominant flow characteristics observed across the four geometries, including smooth front movement (Case a), flow reflection and turbulence (Case b), jet impact and splash behavior (Case c), and the turbulent mixing zone associated with a submerged hydraulic jump (Case d).

Overall, the enhanced MPS method provides a consistent and physically grounded framework for analyzing transient sediment-laden flows. The model reflects the redistribution of energy into permanent bed deformation and dissipation through inter-particle friction, which becomes more significant than viscous losses under rapid flow conditions.

The findings demonstrate that the proposed MPS formulation is a reliable numerical tool for evaluating sediment transport processes and fluid–structure interactions under extreme unsteady flow conditions. In addition, the results highlight the contrasting influence of bed discontinuities, where elevated structures tend to mitigate mobility (Case b), while sudden drops intensify sediment entrainment and scour development (Case c).