Abstract

The crisis of research integrity triggered by academic misconduct, such as scientific fraud and paper retractions, has emerged as a critical issue demanding urgent resolution within the academic community. Blockchain (BC), with its core features of distributed ledger, peer-to-peer transmission, consensus mechanisms, timestamps, and smart contracts, offers novel technical solutions for research institutions seeking efficient models of research credit supervision. By incorporating the psychological factors of risk perception among decision-makers and the dynamic evolution of behavioral decision-making, and drawing on prospect theory, this study has constructed an evolutionary game model involving researchers, scientific research institutions, and governmental entities to examine BC-enabled research credit supervision. This model analyzes the key determinants influencing scientific research institutions’ adoption of blockchain regulation (BC regulation), elucidates the behavioral characteristics and boundary conditions of research integrity among researchers under this new regulatory paradigm, and reveals the dynamic evolutionary trajectory of collaborative supervision between governments and scientific research institutions. The findings indicate the following: (1) Compared to traditional regulation, the BC regulation demonstrates superior regulatory effectiveness at equivalent levels of researcher integrity and misconduct costs, as well as under identical settings for reputational loss and penalties. (2) In addition to cost considerations and government subsidies, factors such as loss aversion coefficient, risk preference coefficient, and privacy breach losses are critical in influencing research institutions’ decisions to implement BC regulation. (3) The evolution of blockchain-empowered regulatory models encompasses three distinct evolutionary patterns. This study provides a theoretical foundation and a simulation case to optimize regulatory strategy formulation and resource allocation, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of research credit supervision.

Keywords:

blockchain; supervision on scientific research credit of scientific research institutions; prospect theory; evolution game; simulation analysis MSC:

65-11; 90B99; 91A22

1. Introduction

In recent years, the issue of research misconduct has become increasingly prominent [1,2], with frequent negative reports of academic fraud and paper retractions, plunging scientific research institutions into academic scandals and a crisis of integrity [2,3]. Research misconduct gravely undermines the value of science by distorting knowledge, wasting research funding, and damaging the credibility of scientists [4]. Research misconduct is defined as fabrication, falsification, and plagiarism [5]. The global volume of retractions has surged [6], with a record-breaking 10,000+ papers retracted in 2023 alone. This trend underscores the critical and urgent need for enhanced governance of research integrity [7]. Nations are prioritizing the governance of research misconduct. The United States has released “A Framework for Federal Scientific Integrity Policy and Practice” to strengthen research integrity [8]. The National Natural Science Foundation of China has publicized cases of research misconduct to serve as a warning [9,10,11]. The issue of research misconduct persists due to several factors: low costs for researchers who engage in misconduct, a focus on personal gain [12], the lack of data sharing, insufficient openness in credit systems, and the ease with which research misconduct information can be altered [13]. This leads to concealed misconduct, the alignment of interests between scientific research institutions and researchers, and the flexible application of penalties by scientific research institutions, which allows misconduct to continue despite repeated attempts to stop it [14]. Consequently, mitigating research misconduct among researchers within scientific research institutions has emerged as a pressing practical and theoretical challenge.

BC and AI-powered audit systems, as cutting-edge technologies in the context of digital transformation, offer promising governance pathways for addressing and mitigating scientific misconduct. Although AI-driven audit systems can intelligently detect anomalies in research data and predict risks [15,16], they face limitations such as heavy reliance on the scale and quality of training data, as well as limited interpretability due to algorithmic opacity. In contrast, BC, regarded as one of the most disruptive technologies of the Fourth Industrial Revolution [17,18], leverages its immutability and traceability to establish a trustworthy timeline for research processes from the outset. This not only provides a high-quality data foundation for subsequent audits but, more importantly, creates a supervision mechanism that does not rely on central authority, fundamentally transforming how research trust is generated. Therefore, BC can empower scientific research institutions to oversee researcher misconduct, serving as an effective solution to address academic impropriety [19,20]. For instance, the Chenzhou Science and Technology Bureau in Hunan Province, China, has implemented a BC-based platform for research integrity supervision, involving regulatory agencies, scientific research institutions, and the public. Nevertheless, real-world applications remain scarce, underscoring the need to explore factors hindering the adoption of BC in empowering research credit supervision.

China’s “delegation, regulation, and service” policy has led to increased governmental involvement in the governance of research integrity, transforming it into a complex system involving researchers, scientific research institutions, and governments. This system exhibits characteristics of dynamism and variability, rendering BC-enabled oversight of research credit an evolving process. Evolutionary game theory provides a scientifically sound analytical framework for this purpose. It characterizes the dynamic process in which decision-makers adaptively adjust their strategies over time. This framework has been applied to contexts such as BC and agricultural supply chains [21,22], financial supply chains [23], data sharing [24,25], and privacy protection [26]. Furthermore, research misconduct is associated with the utilitarian mindset of researchers [12,27], who often prioritize personal advancement and promotion, leading to short-term gains. Existing studies have largely overlooked the role of risk perception in this context, failing to account for how researchers’ awareness of risks fluctuates under regulatory oversight. Prospect theory offers a framework to address the inconsistency between risk perception and decision-making behavior [28,29], positing that decision-makers evaluate gains and losses relative to a reference point rather than in absolute terms, often resulting in overestimation of low-probability events and underestimation of high-probability ones.

This study constructs an evolutionary game model for the credit regulation of scientific research institutions, involving researchers, scientific research institutions, and governments, from the perspective of BC empowerment. The analysis addresses the following questions: (1) How does BC facilitate research credit regulation in comparison to traditional regulation? (2) What are the factors hindering the adoption of BC by scientific research institutions? (3) What is the evolutionary pattern of the BC-enabled research credit regulation model? (4) How does BC influence researchers’ behaviors under varying levels of risk perception?

The contributions of this study are as follows: Firstly, this study constructs a tripartite evolutionary game model involving researchers, scientific research institutions, and governments under BC-enabled scientific research credit supervision. This framework expands the structure of game participants and enhances the generalizability of the game model, aligning with the practical context of research credit supervision by scientific research institutions under the current “delegation, regulation, and service” policy. Secondly, by integrating prospect theory and focusing on psychological perspectives, this study examines the influence of risk perception factors among game participants on the evolution of BC-enabled research credit supervision by scientific research institutions. This approach addresses the limitations of expected utility in traditional evolutionary game theory. Thirdly, given the scarcity of practical cases applying BC to research credit supervision, this study investigates the impact of factors such as cost, benefit, risk perception level, reputation loss, characteristics of traditional regulation, and features of BC regulation on the equilibrium and stability of the evolutionary game system. It analyzes key factors influencing the adoption of BC by scientific research institutions and verifies the feasibility of BC in reducing research misconduct among researchers by comparing the effects of traditional and BC-based supervision on research behaviors. This provides a theoretical foundation and simulation case for whether research supervision entities should adopt BC. Finally, this study identifies the evolutionary pathways of BC-enabled research credit supervision models and the optimal evolutionary trajectory for such supervision models. It further analyzes how to adjust government policy design to shift the evolutionary path from conventional path to the optimal path. This offers a theoretical basis for future national policies aimed at incentivizing scientific research institutions to adopt BC for research credit supervision.

The remaining sections of this study are organized as follows: Section 2 reviews relevant literature; Section 3 introduces the model variables and hypothesis conditions, and constructs the evolutionary game model; Section 4 analyzes the stable strategies within the evolutionary game framework; Section 5 presents case studies and numerical simulation analyses; and Section 6 concludes with research findings, managerial implications, limitations, and future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Impact of BC on Scientific Research Credit Supervision

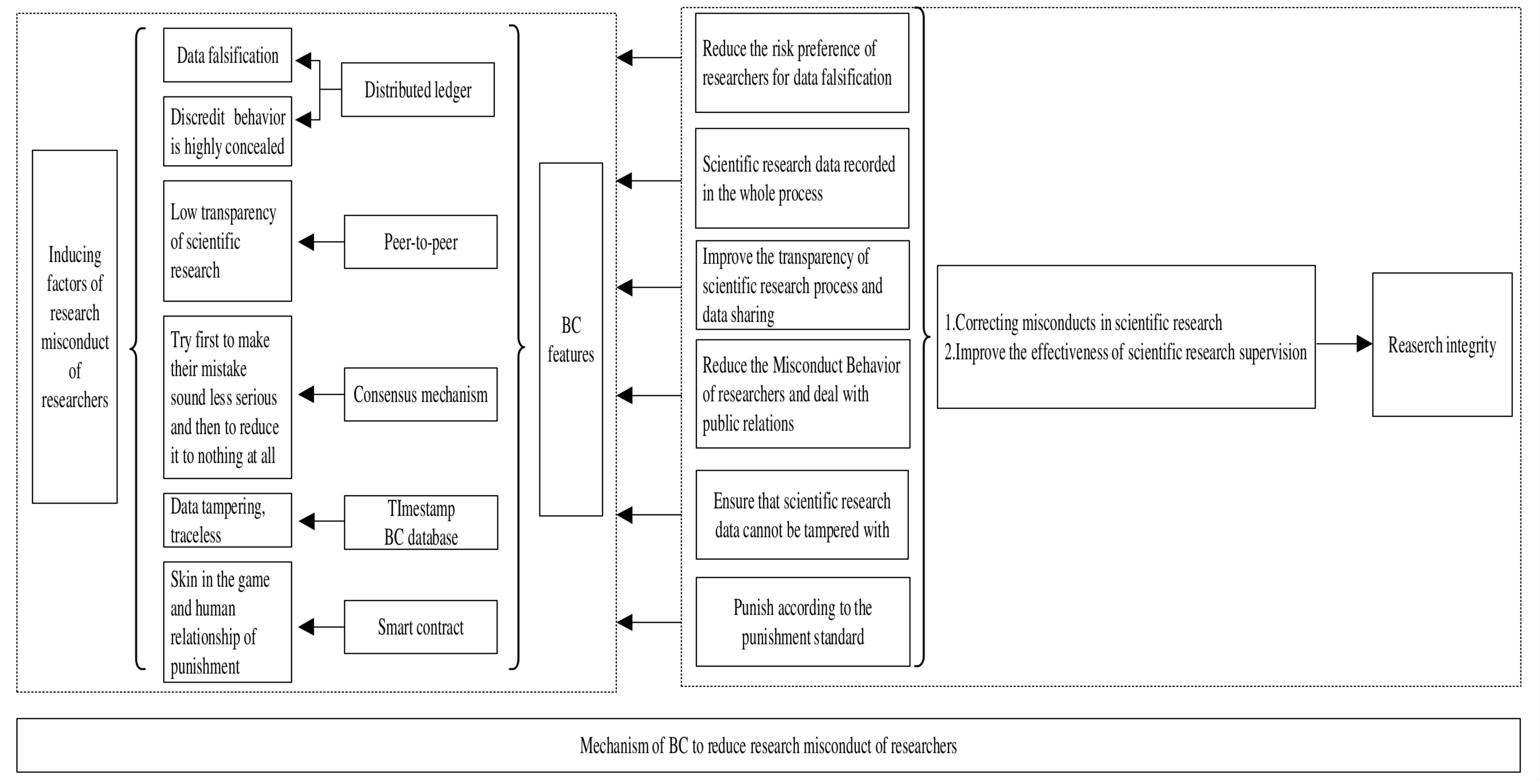

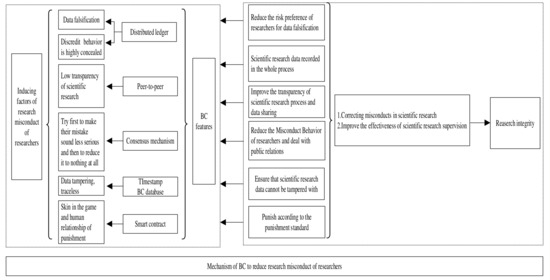

BC offers several advantages that can enhance the credibility regulation of scientific research institutions. Distributed ledger systems enable the establishment of public [30], private, and consortium BCs [31,32] involving key research oversight entities such as authors, accreditation agencies, and experts, thereby recording the entire research data lifecycle. Peer-to-peer transmission facilitates data sharing among regulatory bodies, including accreditation institutions and experts, effectively eliminating information asymmetry. The consensus mechanism designates nodes to record misconduct information and disseminates it throughout the entire network to ensure authentication, recording, and traceability [33], thereby enhancing transparency [34]. Timestamping prevents tampering with the chronological integrity of research data [13], ensuring an auditable record of research activities. BC databases such as LedgerDB, VeDB, and SecuDB can prevent researchers from illicitly tampering with scientific research outcomes. Specifically, LedgerDB is a centralized ledger database that supports unified auditing and verification for applications involving mutually distrustful parties [35,36]. VeDB is a trusted relational database that integrates hardware and software. It offers both high-performance trust capabilities and support for practical tamper-resistant applications [37], thereby enhancing data security and integrity [38,39,40]. SecuDB, a relational database operating within a hardware-encrypted enclave, employs full hardware encryption to achieve privacy preservation and verifiable functionality [41]. Smart contracts automatically enforce penalties for research misconduct according to predefined standards [42], addressing issues of subjective or nepotistic sanctions that may arise from personal relationships between researchers and scientific research institutions. Refer to Figure 1 for a visual depiction of this mechanism.

Figure 1.

Mechanism of BC in reducing research misconduct of researchers in scientific research-competent units.

2.2. Factors Hindering Scientific Research Institutions from Adopting BC

Existing research indicates that BC has not been widely adopted [43,44], primarily due to cost considerations and the influence of government subsidies. On one hand, the high costs associated with implementation [45], maintenance [46], upgrades [47], and economic benefits [48,49] pose significant barriers. On the other hand, government subsidies are insufficient to offset these initial costs [44]. Additionally, BC systems are vulnerable to cyberattacks, which can lead to the leakage of user privacy [47,50]. The decentralized ledger and peer-to-peer transmission mechanisms further increase the risk of sharing sensitive user information [46,49].

2.3. Scientific Research Credit Supervision

Previous research on scientific misconduct has predominantly employed qualitative methodologies such as bibliometric analysis [51], meta-analysis [4], interviews [27,52,53,54], and case studies [55], with a primary focus on investigating the underlying causes of research misconduct and corresponding countermeasures. Gorman et al. [56] advocated for the application of quantitative approaches, specifically mathematical modeling, to examine research integrity and assess the feasibility of enhancing scientific integrity. A minority of scholars have begun to utilize evolutionary game theory models in this domain. Prior studies have mainly concentrated on the strategic interactions between two principal stakeholders, including governments and researchers [57], research sponsors and researchers [58], university management departments and researchers [59], as well as project managers and researchers [60]. However, these findings are increasingly incompatible with the current Chinese context, where the “delegation, regulation, and service” policy has transformed the government’s involvement in research misconduct governance. Research credit regulation now involves a complex system comprising researchers, scientific research institutions, and governments, characterized by dynamic and variable interactions. Consequently, BC-enabled research credit management within scientific research institutions is an evolving process subject to continuous adaptation. Furthermore, research misconduct is associated with researchers’ utilitarian mindsets [61], where considerations of career advancement and promotion drive short-term, opportunistic behaviors.

Despite prior studies, several critical gaps remain. Firstly, privacy risk factors constitute a significant barrier to the adoption of BC, a consideration that has been largely overlooked in existing research. Secondly, there is a lack of investigation into the evolutionary processes of research credit regulation based on BC within scientific research institutions, as well as the exploration of patterns for the evolution of BC-enabled research credit regulatory models. Thirdly, the association between research misconduct and researchers’ utilitarian attitudes is inadequately addressed [12]; current models, which rely on expectation effect-based evolutionary game theory [62], often ignore risk perception factors such as risk aversion and risk preference. In particular, within the context of BC-enabled research credit regulation by scientific research institutions, insufficient attention has been paid to how researchers’ risk cognition evolves and influences their behavior.

3. Problem Description, Assumptions, and Parameter Setting of Model

3.1. Problem Description

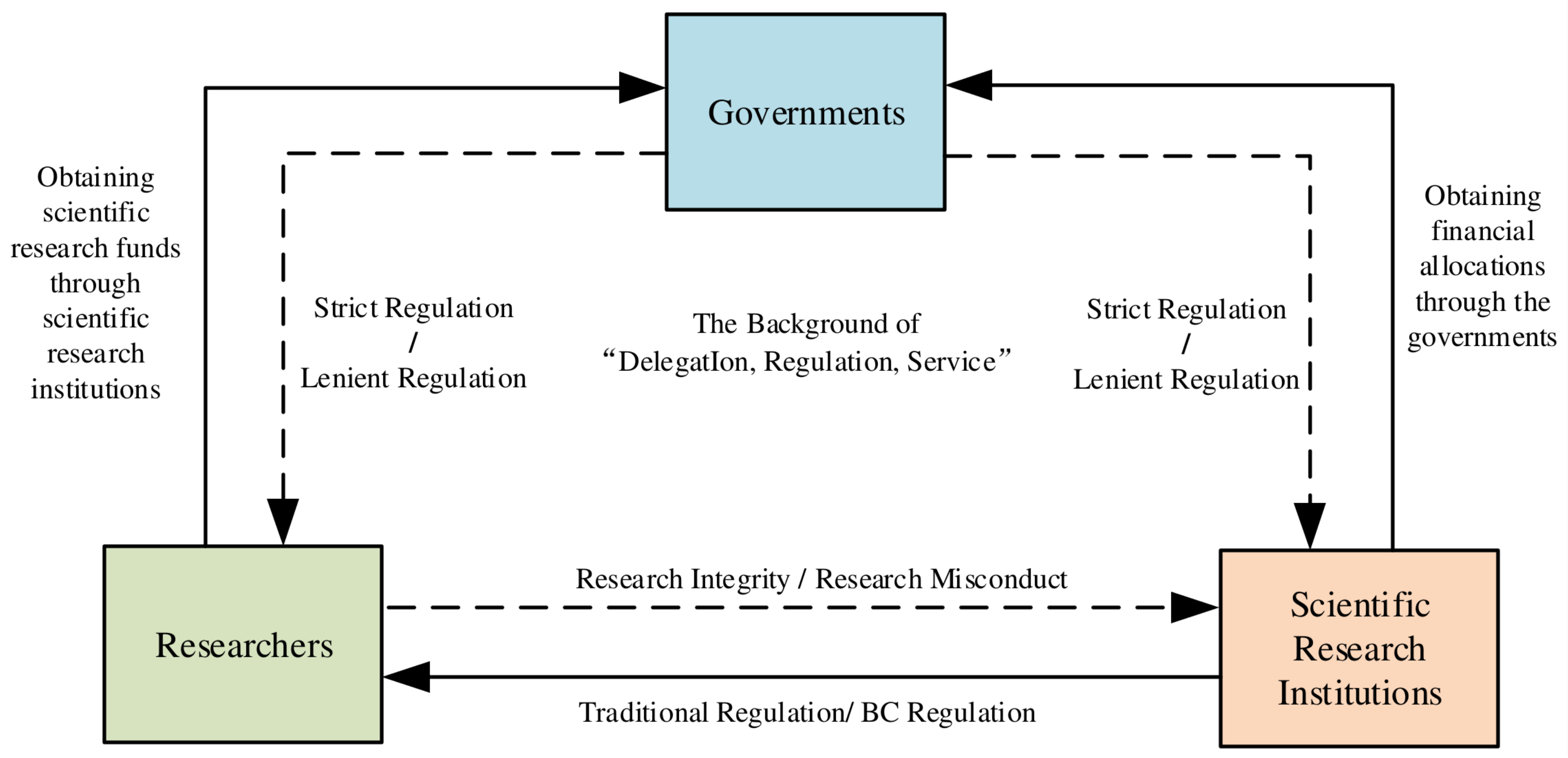

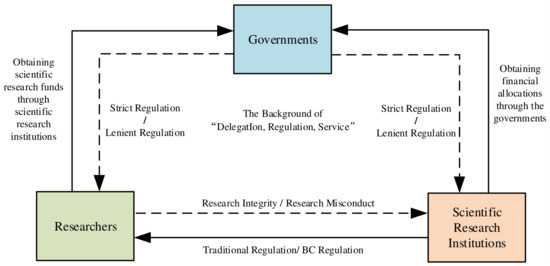

Under the context of the “delegation, regulation, and service” reform by the government, scientific research institutions have been granted substantial autonomy in managing funding, projects, and academic achievements. This shift presents significant challenges to the regulation of research integrity, given the complex interests among researchers, scientific research institutions, and governments. The differing focuses and demands of these stakeholders result in strategic behaviors that are not only influenced by their own benefits but also have profound impacts on the cost–benefit considerations of other participants. The regulation of research integrity within scientific research institutions manifests as an interactive strategic game involving researchers’ integrity-related decision-making, the transition between traditional and new regulatory approaches by scientific research institutions, and the design of governments. Consequently, this study constructs a tripartite evolutionary game model elucidating the logical relationships among the three principal actors in BC-enabled research integrity regulation, as depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Logic diagram of tripartite evolutionary game model.

Researchers’ choice to uphold research integrity is primarily driven by their academic ethical standards and compliance with relevant laws and policies established by governments and scientific research institutions. This commitment often aims to secure research funding through institutional platforms and emphasizes the long-term benefits of scientific achievement. Conversely, the decision to engage in research misconduct may stem from self-interested, short-sighted attitudes or heightened risk perception [12], with motivations centered on accelerating professional title advancement, enhancing project prestige, increasing research funding, and prioritizing short-term academic gains [63].

Although the governments do not directly oversee researchers, as the primary administrators of scientific research institutions, they can implement supervisory mechanisms, such as formulating policies on research credit regulation and disseminating them to research entities to achieve indirect oversight of researchers. Under the “delegation, regulation, and service” framework, the government opts for a “regulation” approach, emphasizing strict regulation of scientific research institutions and personnel to foster research integrity, combat research misconduct, and cultivate a conducive research environment that promotes technological innovation. Conversely, the “relaxation” approach involves lenient regulation constraints on research entities and personnel, aiming to mitigate administrative burdens associated with performance-driven evaluations or to balance regulatory costs [63].

As policy implementers and direct managers of researchers, scientific research institutions are tasked with both executing government-mandated research credit regulation policies and supervising the conduct of researchers. When selecting BC regulation, scientific research institutions can benefit from the technology’s advantages, such as distributed ledger technology, peer-to-peer transmission, immutability, timestamping, and smart contracts, all of which enhance the effectiveness of research credit supervision, reduce instances of research misconduct, and foster a culture of integrity. Additionally, adopting BC can bolster the overall research capacity of the institution and facilitate the cultivation of top-tier talent. Conversely, scientific research institutions opt for traditional regulation, primarily due to cost considerations or concerns over privacy breaches. They may also prefer to downplay or minimize exposure of research misconduct issues to mitigate potential reputational damage [63].

3.2. Assumptions and Parameter Setting of Model

To develop a BC-enabled research credit regulation game model for scientific research institutions, this study analyzes the strategic choices of researchers, scientific research institutions, and governments, examining the influence relationships among key elements and their dynamic evolutionary processes, based on the following assumptions:

Hypothesis 1.

Researchers are designated as Participant 1, scientific research institutions as Participant 2, and governments as Participant 3. All three parties are boundedly rational actors, initially operating at a nascent stage. Over time, their strategic choices evolve through a dynamic process, gradually stabilizing toward optimal strategies within the evolutionary game framework. The researchers strategy set is {research integrity, research misconduct}. The probability of “research integrity” is equal to (), and the probability of “research misconduct” is equal to . The scientific research institutions strategy set is {BC regulation, traditional regulation}. The probability of “BC regulation” is equal to (), and the probability of “traditional regulation” is equal to . Governments strategy set is {strict regulation, lenient regulation}. The probability of “strict regulation” is equal to (), and the probability of “lenient regulation” is equal to .

Hypothesis 2.

Drawing on prospect theory, researchers, scientific research institutions, and governments exhibit heterogeneity in risk perception and preference, information acquisition and analysis, and knowledge levels. These differences in subjective evaluation of gains and losses influence strategic choices and system stability, as each game-theoretic agent assigns new value to objective outcomes based on individual cognitive biases and risk preferences. The existing literature [62,64,65] predominantly adopts 0 as the reference point to analyze the impact of agents’ risk preferences on strategy selection; accordingly, this study sets .

According to prospect theory [63,64,66], the expected total utility of strategies for researchers, scientific research institutions, and governments is evaluated through the value function and the weighting function , with the prospect value represented as . The parameter denotes the decision-making process of game participants based on their perceived value of gains and losses, with the value function expressed as Equation (1):

Here, () denotes the risk preference coefficient. The parameter reflects the degree of diminishing marginal sensitivity to gains and losses for the game participants. A lower indicates a higher risk preference, while signifies risk neutrality. The parameter () represents the loss aversion coefficient; a higher value indicates greater sensitivity to losses among the game participants. Additionally, decision-makers form subjective judgments based on the probability of events, as expressed in Equation (2):

Here, denotes the objective probability of event occurring. When is small, , indicating that low-probability events are typically overestimated; conversely, when is large, , signifying that high-probability events are generally underestimated. Additionally, and . The parameter () represents the decision sensitivity coefficient. A higher value of reflects a greater subjective discrimination rate among game participants.

Hypothesis 3.

When researchers adopt research integrity, they incur a cost denoted as ; conversely, adopting research misconduct incurs a lower cost, . If scientific research institutions implement BC regulation, researchers engaging in misconduct are subject to an additional psychological deterrence cost, , where . Under traditional regulation, when researchers engage in research misconduct, there is a probability that such misconduct will be exposed, resulting in a reputational loss of and a financial penalty of imposed by scientific research institutions. Here, () represents the interpersonal penalty coefficient, reflecting the interest alignment between researchers and scientific research institutions as posited by the stakeholder theory, which incentivizes scientific research institutions to minimize penalties for dishonest behavior to support their own development. The parameter () denotes the probability that scientific research institutions identify misconduct under traditional regulation. In contrast, under BC regulation, any instance of research misconduct is invariably exposed, leading to a reputational loss and a financial penalty imposed by scientific research institutions, as depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Relevant parameters and their meanings.

Hypothesis 4.

When scientific research institutions implement BC regulation, they receive government subsidies denoted as , while incurring costs (encompassing BC infrastructure development, maintenance, and related expenditures). The cost of BC regulation is . Given the inherent privacy leakage risks associated with BC, there exists a probability () that research output data from both scientific research institutions and researchers may be exposed, resulting in a loss quantified as . If traditional regulations are adopted, the associated cost is , where . Under BC regulation, should researchers engage in research misconduct, scientific research institutions suffer a reputational loss of (where , reflecting the mitigating effect of BC oversight on negative reputational impact ), and researchers are subject to a penalty imposed by scientific research institutions. Conversely, under traditional regulations, research misconduct by personnel results in a reputational loss for scientific research institutions, a penalty for researchers, and a penalty for scientific research institutions imposed by governments, as depicted in Table 1.

Hypothesis 5.

Governments incur a regulatory cost of under a strict regulation and under a lenient regulation, with . When governments implement a strict regulation, if researchers engage in research misconduct, governments suffer a reputational loss ; however, the negative impact is partially mitigated by a factor () due to the strict regulation, and scientific research institutions are subject to a penalty imposed by governments. Conversely, under a lenient regulation, if researchers commit research misconduct, governments also incur a reputational loss , but lenient regulation does not mitigate the negative impact by any proportion , as depicted in Table 1.

3.3. Description and Analysis of the Basic Model

Based on the aforementioned assumptions, the perceived payoff matrix for the evolutionary game involving researchers, scientific research institutions, and governments is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Perceived payment matrix of evolutionary game involving researchers, scientific research institutions, and governments.

Based on the perceived payoff matrix and prospect theory, the expected prospect values for researchers adopting either research integrity or research misconduct, as represented in Equations (3) and (4), and the average expected prospect value in Equation (5), are simplified as follows:

The expected prospect values for scientific research institutions adopting BC regulation or traditional regulation, as represented by Equations (6) and (7), along with the average expected prospect value in Equation (8), are simplified as follows:

The expected prospect values for the governments’ choice between strict regulation and lenient regulation, as represented by Equations (9) and (10), and the average expected prospect value as shown in Equation (11), are simplified as follows:

Accordingly, the replicator dynamic equations for strategy selection by researchers, scientific research institutions, and governments, namely Equations (12)–(14), can be simplified and expressed as follows:

4. Model Analysis

4.1. For Researchers

The replicator dynamic equation governing researchers’ strategic choices is expressed as (12), with the first derivative of and the specified function defined as follows:

According to the stability theorem of differential equations, the probability of researchers’ strategic choices reaches equilibrium when conditions and . From , it follows that ; from , it follows that .

Proposition 1.

If condition holds, then

consistently constitutes an evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS). If condition is satisfied, then (1) when occurs, all reach a stable equilibrium; (2) when is present, emerges as the evolutionarily stable strategy; and (3) when arises, becomes the evolutionarily stable strategy.

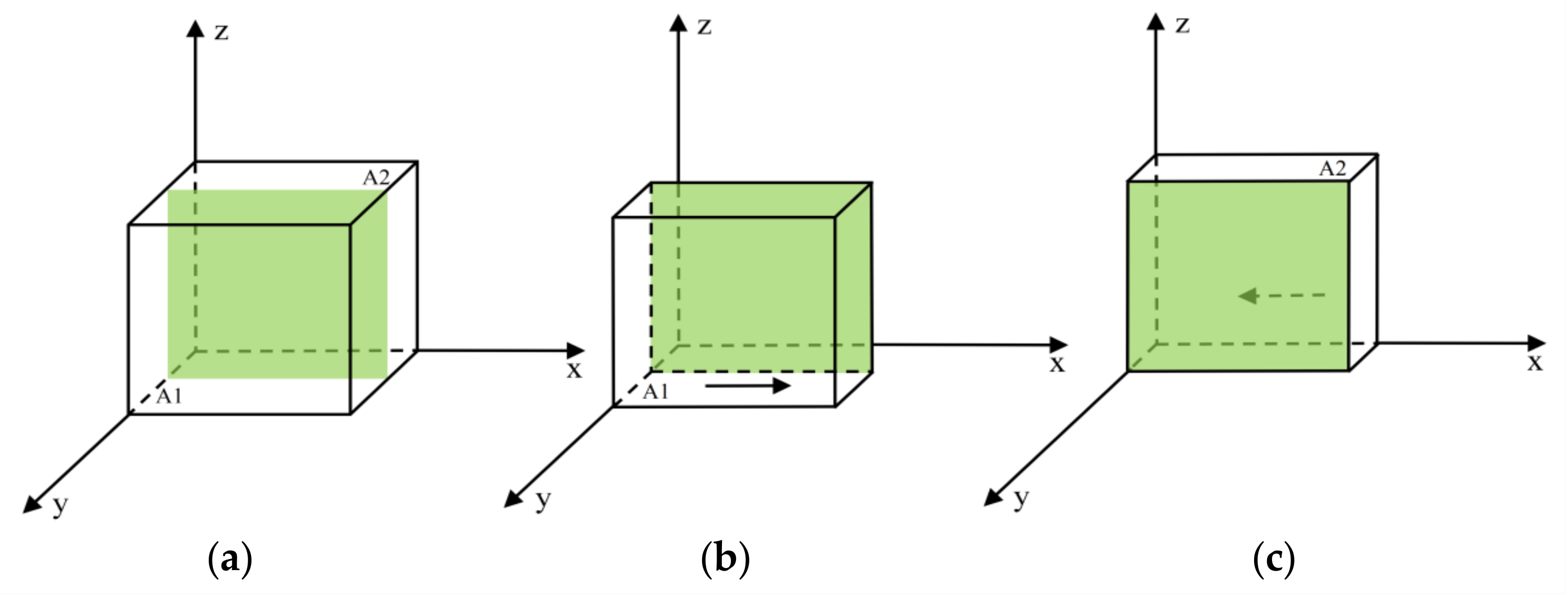

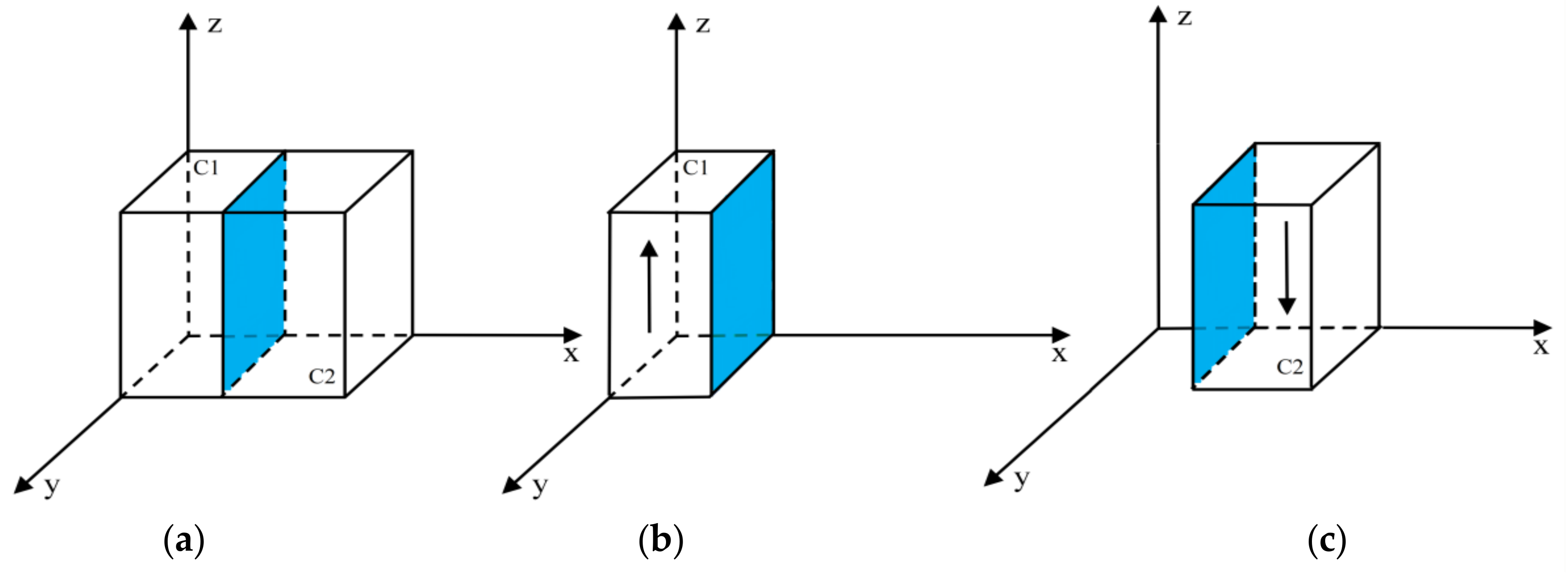

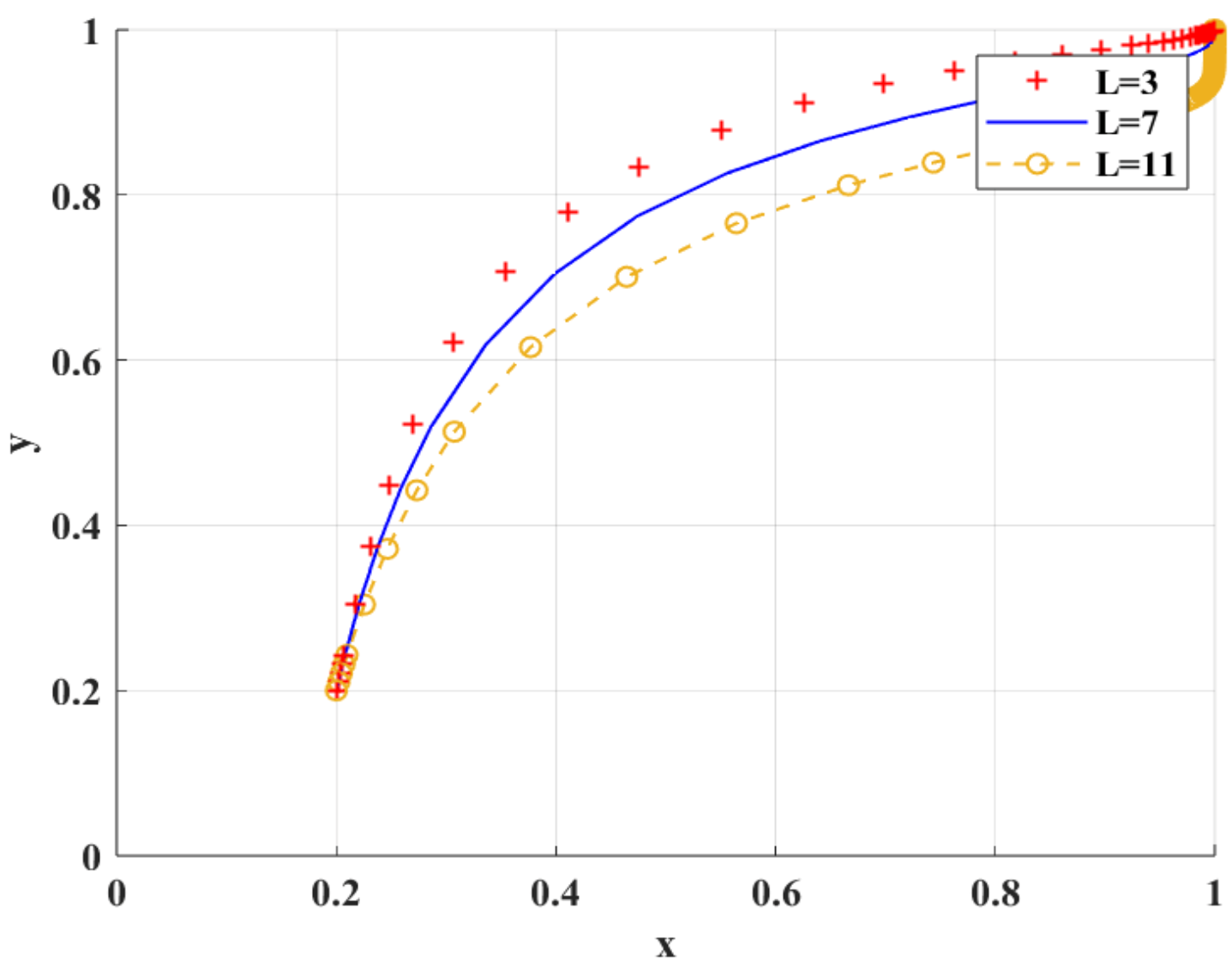

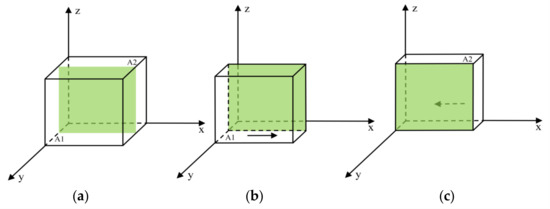

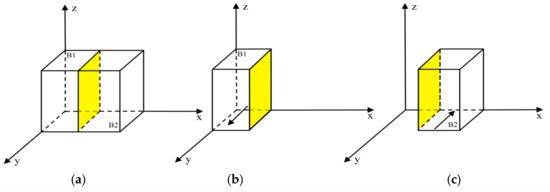

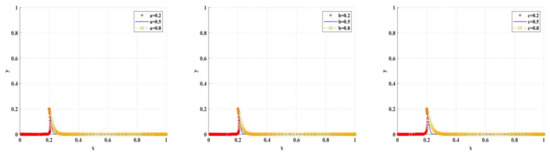

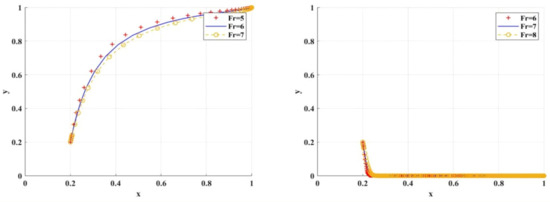

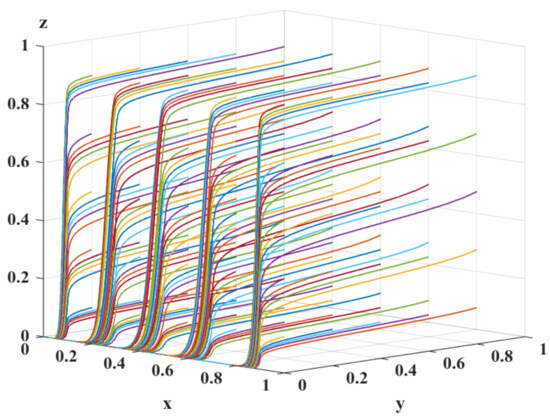

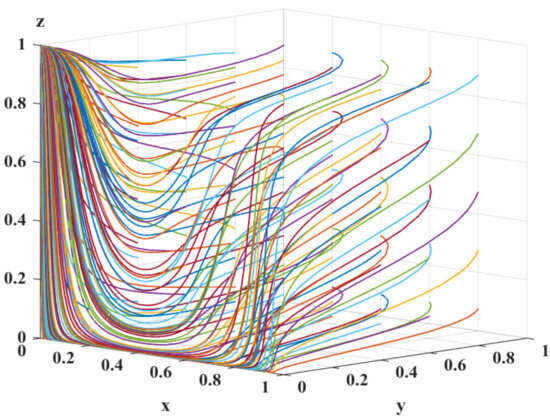

Proposition 1 indicates that researchers’ strategic choices are influenced by the comparative magnitude of the combined reputation loss and penalty () relative to the differential cost of research strategy investment (). Specifically, (1) when the sum of reputation loss and penalties exceeds the differential investment cost, researchers will uniformly adopt research integrity regardless of the regulatory approach employed by scientific research institutions and governments; (2) when this sum is less than the differential investment cost, researchers’ strategic decisions depend on the regulatory strategies selected by scientific research institutions. At a certain probability of institutional strategy choice, researchers’ strategies remain at an initial equilibrium, as illustrated in the green shaded area of Figure 3a. When scientific research institutions favor BC regulation, researchers’ strategies stabilize in research integrity, as shown in Figure 3b (A1). Conversely, when scientific research institutions prefer traditional regulation, researchers’ strategies stabilize in research misconduct, as depicted in Figure 3c (A2).

Figure 3.

Phase diagram of researchers’ strategy evolution: (a) , (b) , and (c) .

4.2. For Scientific Research Institutions

The replicator dynamic equation governing strategic choices in scientific research institutions is represented by (13), with the first derivative of and the specified function defined as follows:

According to the stability theorem of differential equations, the probability of strategy selection by scientific research institutions must satisfy conditions and to attain a stable equilibrium. The evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS) for scientific research institutions is as specified in Proposition 2. Deriving from condition yields ; from condition , it follows that .

Proposition 2.

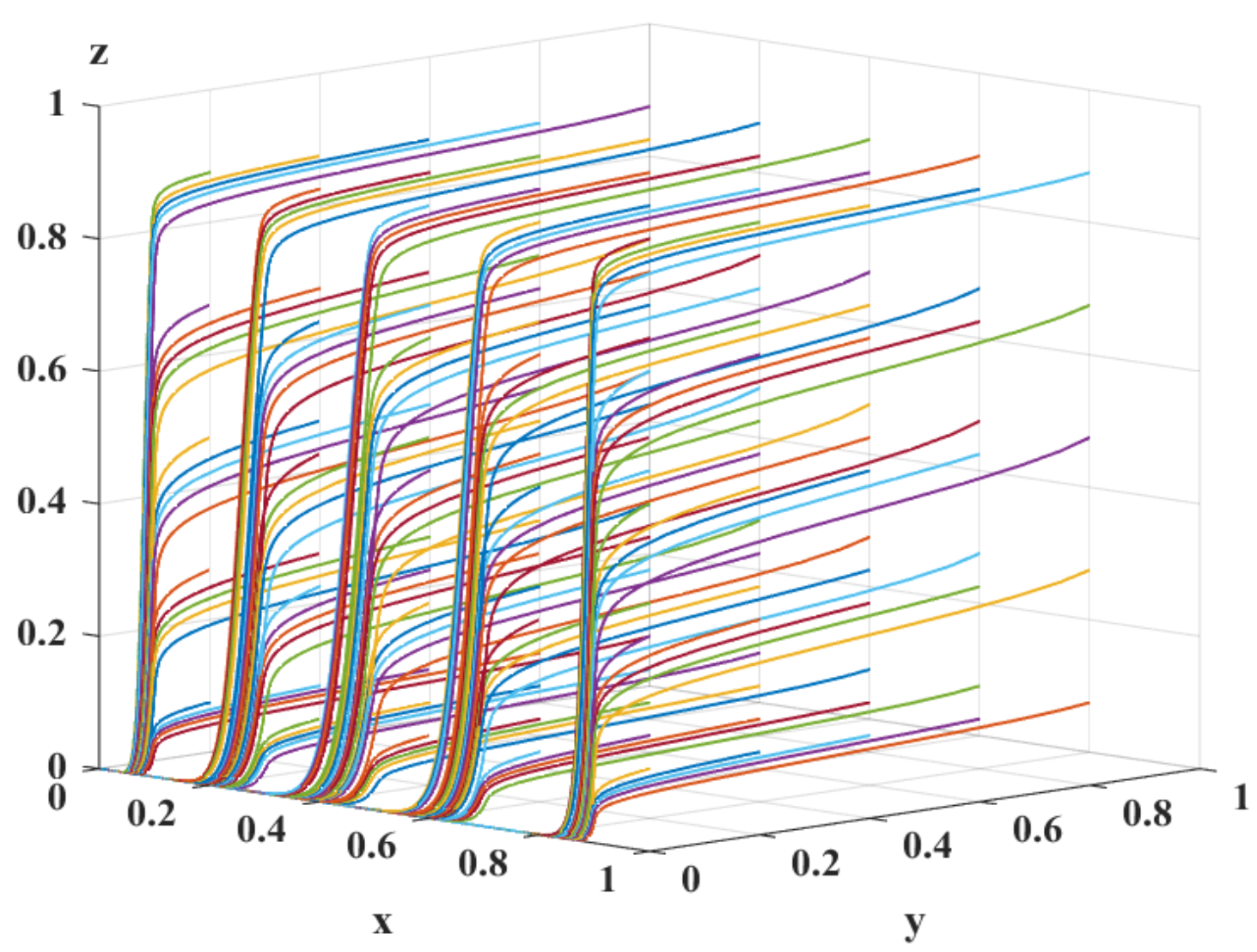

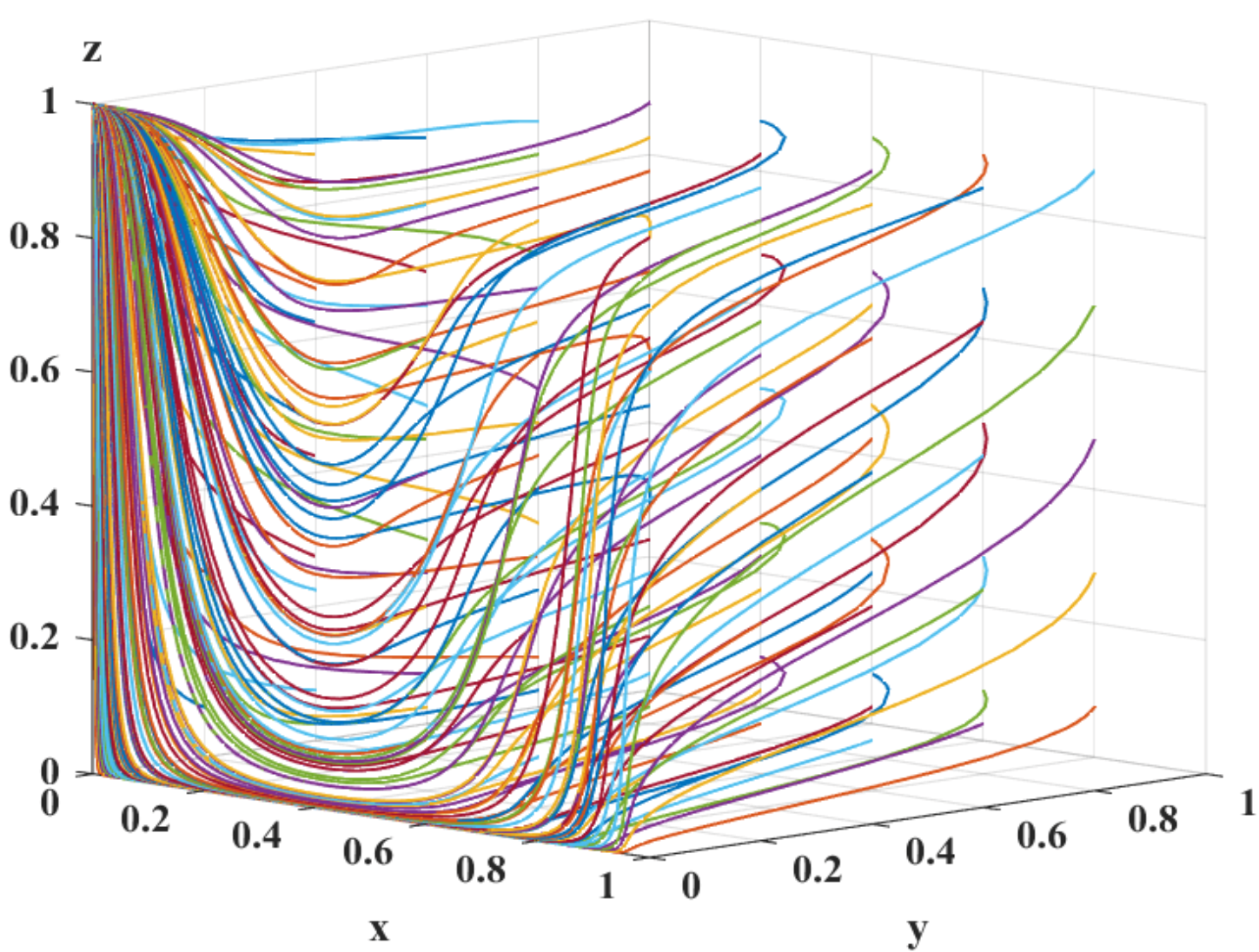

If condition holds, then is an evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS). If condition is satisfied, then (1) under condition , all strategies are evolutionarily stable; (2) under condition , constitutes an ESS; and (3) under condition , is an ESS.

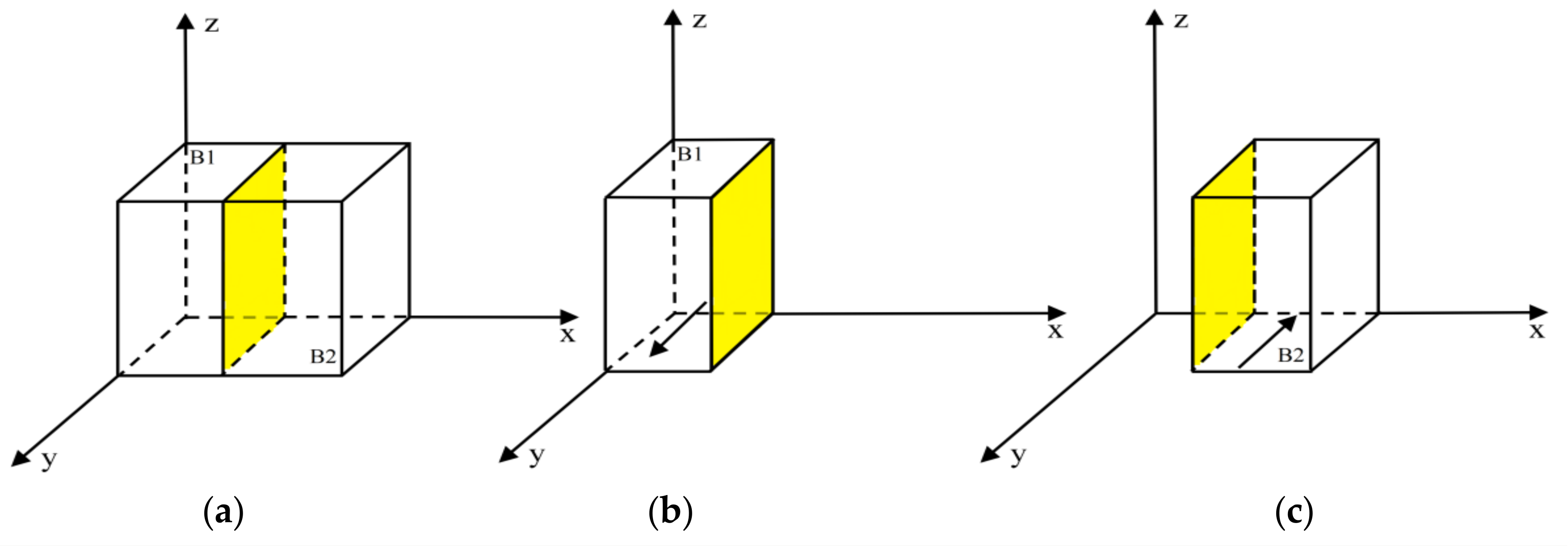

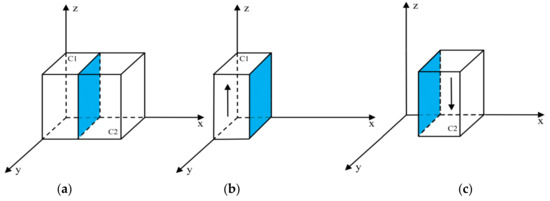

Proposition 2 indicates that the boundary factors influencing scientific research institutions’ adoption of BC regulation primarily encompass three categories: benefits, costs, and self-inflicted losses. Benefits include government subsidies and penalties imposed on researchers for research misconduct; costs comprise the differential in strategy implementation expenses (), routine costs associated with BC integration, and privacy challenges inherent to BC; and self-inflicted losses refer to the reputational damage suffered by scientific research institutions due to researchers’ breach of trust. When the expected benefits for scientific research institutions fall below the combined costs and self-losses, they tend to favor traditional regulation regardless of researchers’ and governments’ strategic choices. Conversely, if the benefits exceed these combined costs and losses, the scientific research institutions’ strategic decision-making depends on the probability of researchers choosing research misconduct: at a specific threshold of , the strategy remains at an initial equilibrium, as illustrated by the yellow shaded region in Figure 4a; when researchers are inclined toward research misconduct, the scientific research institutions’ strategy stabilizes in favor of BC regulation, as depicted in Figure 4b at point B1; and when researchers favor research integrity, the scientific research institutions’ strategy stabilizes under traditional regulation, as shown in Figure 4c at point B2.

Figure 4.

Phase diagram of scientific research institutions’ strategy evolution: (a) , (b) , and (c) .

4.3. For Governments

The replicator dynamic equation governing strategic selection in governments is given by (14), with the first derivative of and the respective definitions of specified as follows:

According to the stability theorem of differential equations, the probability of governments’ strategy selection must satisfy conditions and to attain a stable equilibrium. The evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS) of governments is as delineated in Proposition 3. Derived from condition , it follows that ; and from condition , it follows that .

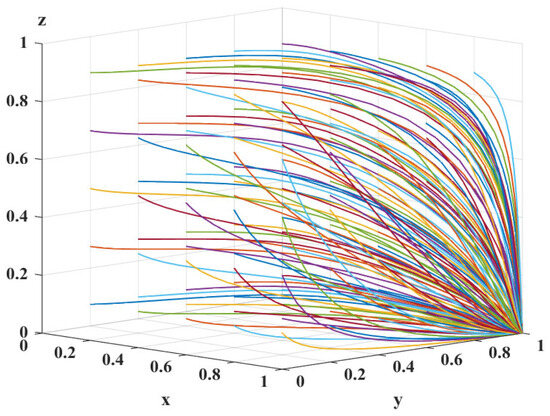

Proposition 3.

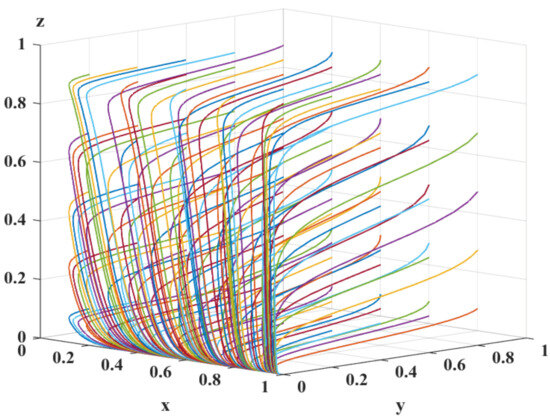

If condition holds, then is an evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS). If condition is satisfied, then (1) when occurs, all strategies z are at evolutionary stability; (2) when occurs, constitutes an ESS; and (3) when occurs, is an ESS.

Proposition 3 indicates that the governments’ strategic choice is influenced by the comparative magnitude of its differential cost () and the combined benefits from penalizing research misconduct, namely, fines and reputational damage. Specifically, (1) when the differential cost exceeds the aggregate of fines and reputational losses, governments adopt a lenient regulation regardless of the strategies employed by researchers and scientific research institutions, and (2) when the differential cost is lower than this aggregate, governments’ regulatory strategy is contingent upon the researchers’ strategic probabilities: at a specific probability of choosing research integrity, governments’ strategy remains at its initial equilibrium, as illustrated by the blue shaded region in Figure 5a. When researchers tend to select research misconduct, governments stabilize their strategy at strict regulation, as shown in Figure 5b (C1), and conversely, when researchers favor research integrity, governments maintain a lenient regulation, as depicted in Figure 5c (C2).

Figure 5.

Phase diagram of governments’ strategy evolution: (a) , (b) , and (c) .

4.4. Stability Analysis of Equilibrium Points in the Three-Party Evolutionary Game System

To investigate the evolutionarily stable strategies (ESSs) within the three-party framework, local stability analysis was conducted utilizing the Jacobian matrix derived from Friedman’s evolutionary game dynamic system [67]. Given that mixed-strategy equilibria in asymmetric evolutionary games do not constitute an ESS [68], the analysis was confined to pure-strategy equilibria of the evolutionary game system. Based on Equations (15)–(17), the Jacobian matrix of the system is obtained as follows:

Here:

According to Lyapunov’s first method, an equilibrium point is asymptotically stable if all eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix possess negative real parts; conversely, if at least one eigenvalue has a positive real part, the equilibrium point is unstable. The eigenvalue analysis results for the eight local equilibrium points, derived from the Jacobian matrix, are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Eigenvalues of equilibrium points.

Proposition 4.

When conditions , , and are satisfied, the evolutionarily stable strategy corresponds to (research misconduct, traditional regulation, lenient regulation), denoted as .

Scenario 1: In this context, BC remains immature and has yet to attract governments’ attention. Considering cost-efficiency, scientific research institutions tend to adopt traditional regulations. Such strategies are prone to induce interpersonal sanctions and undermine researchers’ trustworthiness. Given that the costs associated with maintaining research integrity significantly exceed those of misconduct, and driven by utilitarian motives, researchers are inclined to pursue dishonest practices. Furthermore, the costs of strict regulation enforcement far surpass those of lenient regulation, leading governments to favor lenient regulation and consequently deprioritize the governance of research misconduct.

Proposition 5.

When conditions and are satisfied, the evolutionarily stable strategy corresponds to (research integrity, traditional regulation, lenient regulation), denoted as .

Scenario 2: Following the exposure of research misconduct cases triggered by Scenario 1, governments issued relevant policies to enhance the oversight of research integrity, emphasizing the governance of research misconduct. At this stage, BC remains underdeveloped and has not attracted governmental attention. Due to cost considerations, scientific research institutions continue to prefer traditional regulation; however, in accordance with governmental directives, they are mandated to intensify research integrity supervision, including increasing the detection probability of misconduct and shifting from discretionary sanctions to stringent punitive measures. Given the increased costs and penalties associated with research misconduct, researchers tend to adopt strategies aligned with research integrity. Nonetheless, the high costs of maintaining integrity compared to the relatively lower costs of misconduct, coupled with a utilitarian mindset, lead researchers to favor research misconduct. Although governments have begun to focus on research integrity governance, regulatory authority remains primarily with scientific research institutions, resulting in a continued preference for lenient regulation.

Proposition 6.

When conditions , , and are satisfied, the evolutionarily stable strategy is (research misconduct, traditional regulation, strict regulation), namely .

Scenario 3: As incidents of research misconduct among researchers in Scenario 2 continue to occur with increasing frequency, governments have resolved to intensify governance measures against research integrity violations. Without regard to cost considerations, a strict regulation has been adopted, including the ongoing issuance of policy documents to reinforce oversight of research credibility by scientific research institutions. Additionally, given the maturity of BC, an initial application subsidy policy has been introduced; however, the subsidy magnitude remains limited. During this period, scientific research institutions, driven by cost-efficiency considerations, tend to favor traditional regulation. Over time, as researchers adapt to a high-regulation environment for research integrity, utilitarian motives and cost considerations may lead them to revert to research misconduct.

Proposition 7.

When conditions and are satisfied, the evolutionarily stable strategy corresponds to (research integrity, BC regulation, lenient regulation), denoted as .

Scenario 4: In the context of strict regulation in Scenario 3, instances of research misconduct among researchers persist despite regulatory efforts. To address this, governments enhance subsidies for BC adoption, incentivizing scientific research institutions to implement BC scientific credit supervision. As subsidy levels increase, the comprehensive costs associated with BC application are progressively offset. Moreover, BC regulation advantages surpass those of traditional regulation, prompting research entities to adopt BC regulation. The multifaceted benefits of BC lead to an escalation in the costs and losses associated with research misconduct, eventually exceeding the costs of maintaining research integrity. Consequently, researchers tend to favor strategies aligned with research integrity. Recognizing that the integration of BC improves the efficiency and effectiveness of scientific credit regulation, governments, as an indirect supervisory authority over researchers, gradually diminish their role as the primary regulator and adopt more lenient regulations.

4.5. Analysis of the Evolutionary Model of Research Credit Regulation Empowered by BC in Scientific Research Institutions

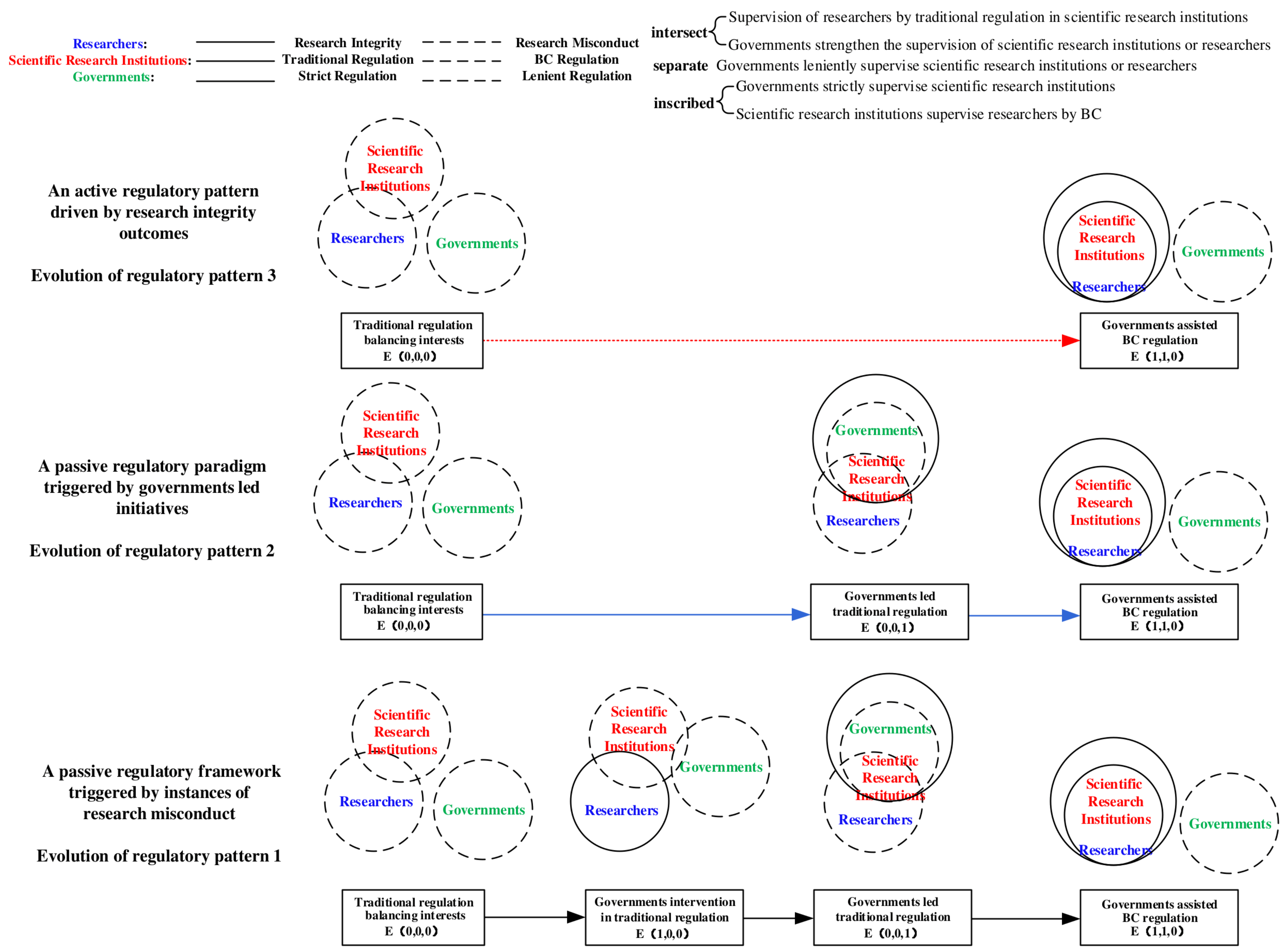

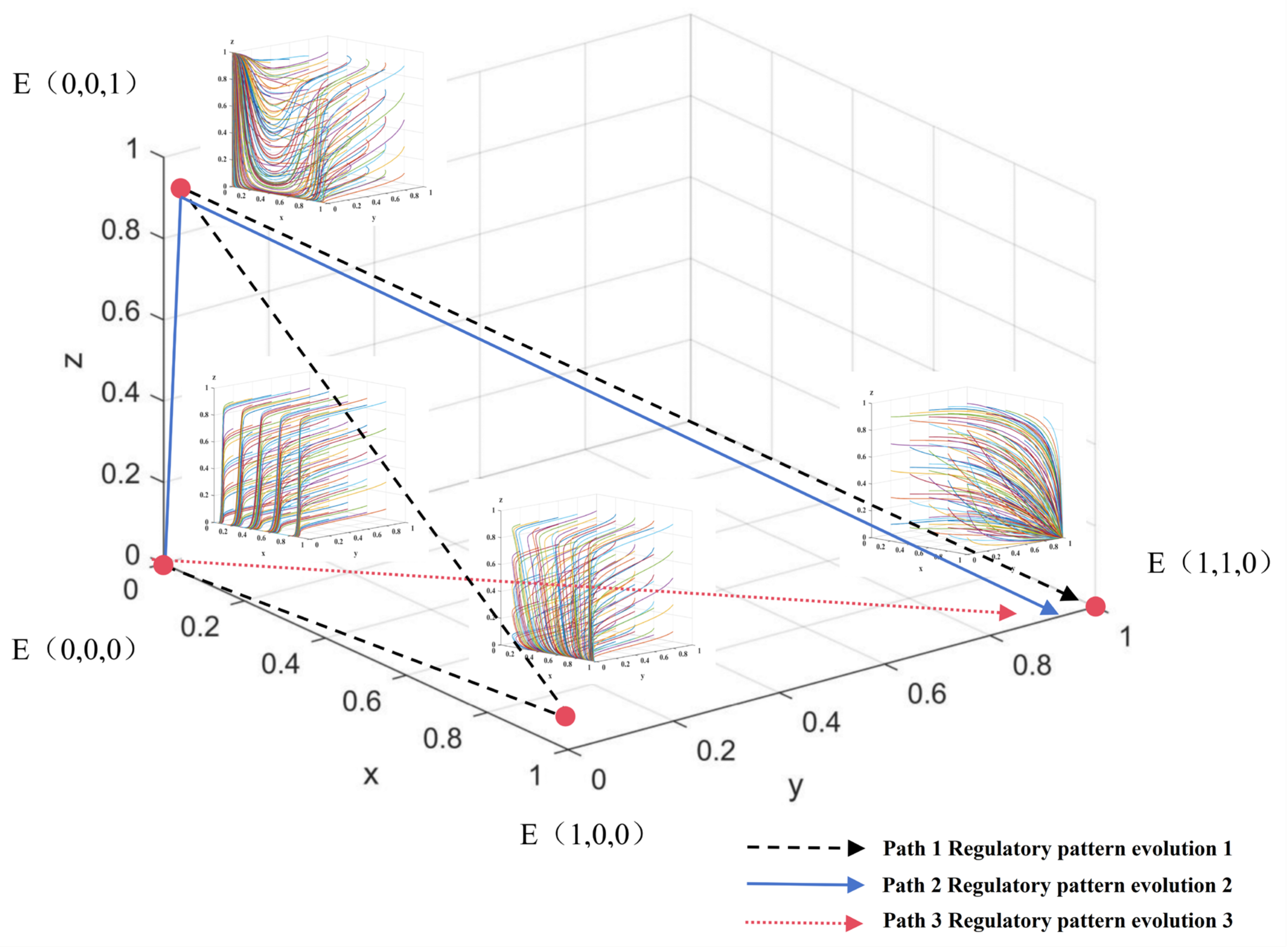

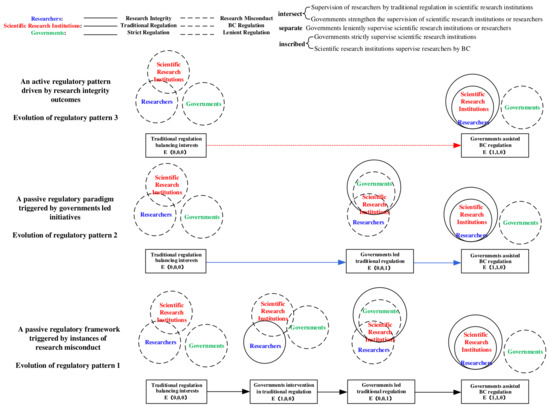

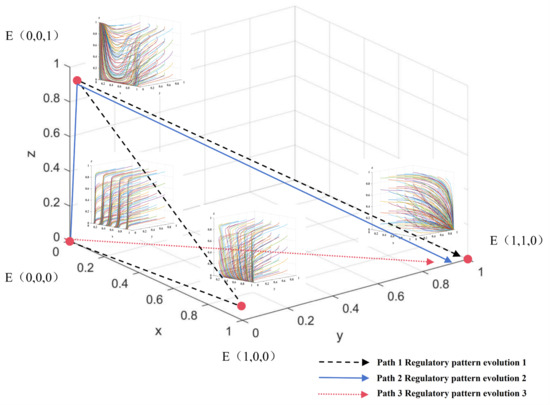

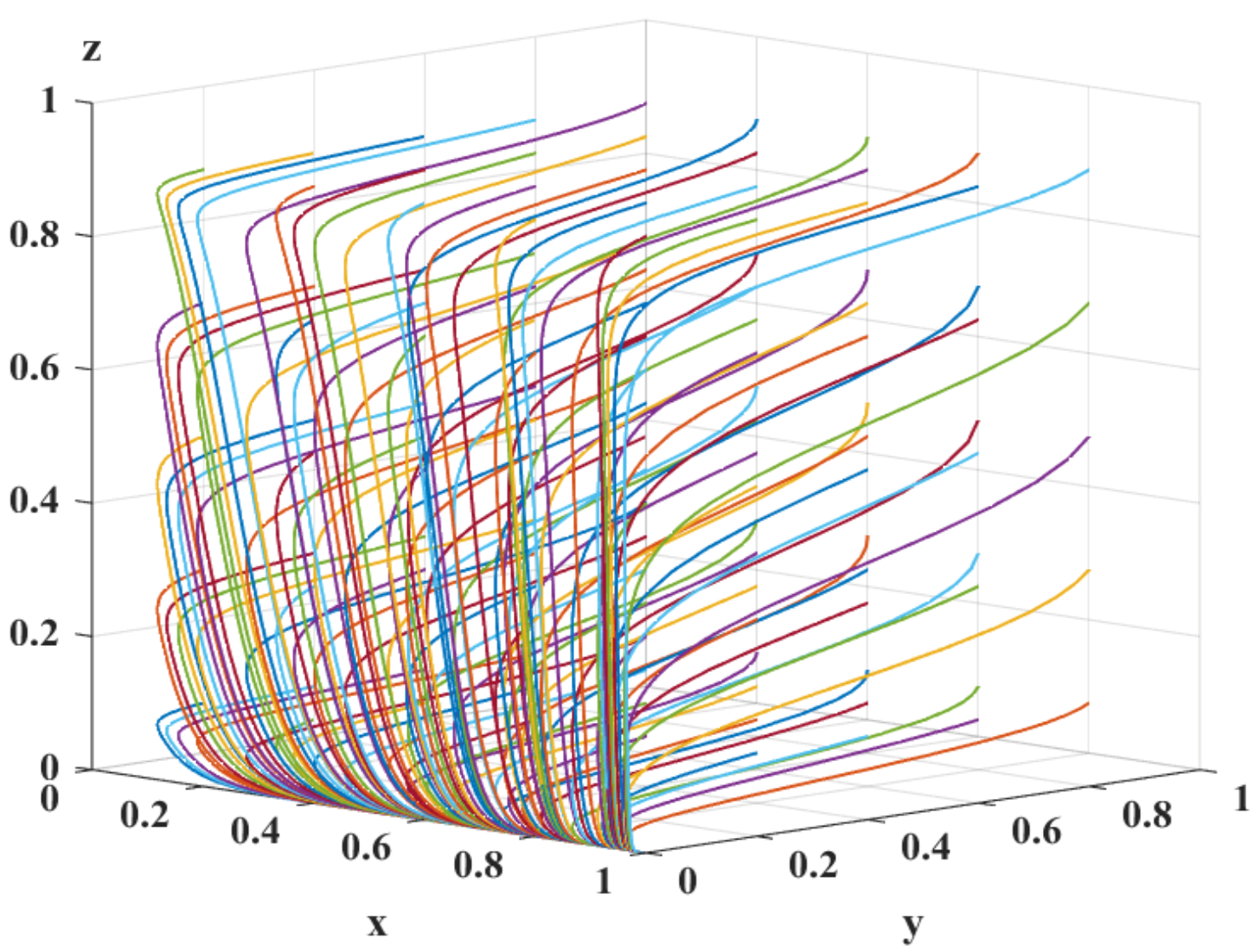

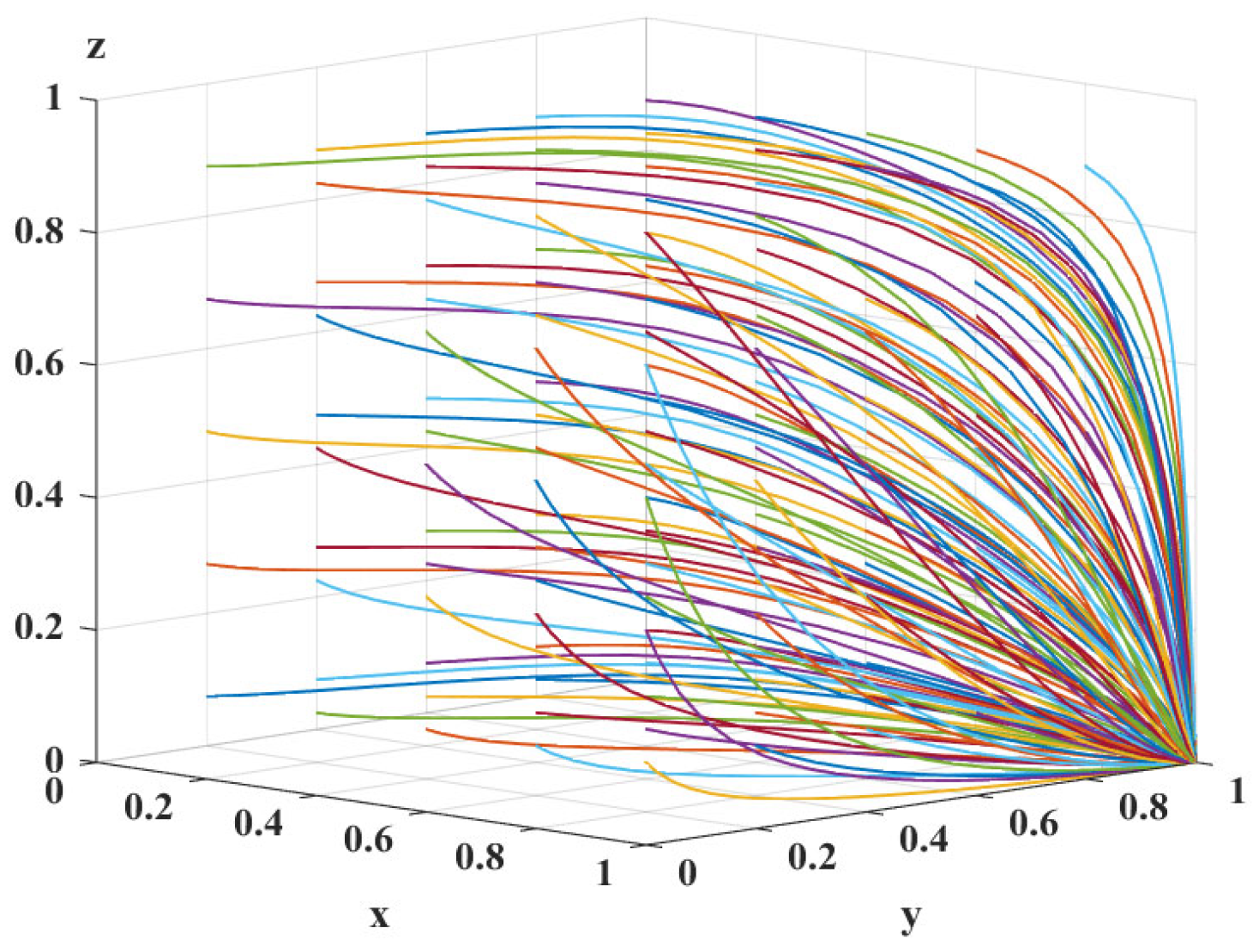

Based on Propositions 4–7, it is evident that the evolution of BC-enabled research integrity regulations within scientific research institutions is jointly constrained by factors such as costs, benefits, and losses. This process manifests in three evolutionary patterns: a passive regulatory pattern triggered by research misconduct outcomes, a government-led passive regulatory pattern, and an active regulatory pattern driven by research integrity results, as illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Evolutionary pattern of scientific research credit supervision of BC-enabled scientific research competent units.

As illustrated in Figure 6, regulatory pattern 1 represents a passive regulatory framework triggered by instances of research misconduct. This pattern encompasses an evolutionary trajectory among four states: traditional regulation balancing interests, government intervention in traditional regulation, government-led traditional regulation, and government-assisted BC regulation. During the interest-balancing phase of traditional regulation, BC remains immature, and governmental attention to its application prospects is limited. Given the developmental needs of scientific research institutions and researchers whose interests are partially aligned, cost considerations and the necessity for interest equilibrium (with overlapping interests between researchers and scientific research institutions) result in the regulatory focus excluding misconduct oversight (external to governments). Under these conditions, the stable strategy for all three parties is Strategy .

In the government intervention phase of traditional regulation, as cases of scientific misconduct become more visible, governments begin to engage in misconduct governance by issuing directives to strengthen research integrity oversight (partial overlap between governments and scientific research institutions). Scientific research institutions respond by intensifying their research credit management efforts (expanding the overlap between researchers and scientific research institutions), leading researchers to favor strategies aligned with research integrity. However, due to the low costs associated with traditional regulation and lenient regulation, the stable strategy remains as Strategy .

During the government-led traditional regulation period, persistent misconduct cases prompt governments to escalate enforcement efforts, adopting a strict regulation (full inclusion of scientific research institutions within governments’ oversight). Concurrently, BC matures, prompting governments to implement BC subsidy policies, albeit with limited funding. Despite this, scientific research institutions tend to prefer traditional regulation, although regulatory intensity increases further (expanding the overlap between researchers and scientific research institutions). Over time, researchers adapt to the heightened regulatory environment, and being driven by utilitarian motives and cost considerations, revert to research misconduct, establishing Strategy as the stable equilibrium.

In the BC-assisted regulation phase, misconduct cases continue to emerge. Governments respond by increasing BC subsidies, gradually offsetting the comprehensive costs of BC adoption. Owing to the superior regulatory advantages of BC over traditional regulation, such as the full integration of scientific research institutions within the BC network and the internalization of researchers within scientific research institutions, misconduct behaviors are significantly mitigated. Consequently, governments begin to diminish their dominant role in research credit regulation (external to governments), leading to a stable Strategy among all three parties.

A passive regulatory paradigm triggered by government-led initiatives is characterized by the evolutionary trajectories among three states: traditional regulation balance of interests, government-led traditional regulation, and government-assisted BC regulation, collectively denoted as .

An active regulatory pattern driven by research integrity outcomes, characterized by the evolutionary trajectory between traditional regulation and its balance of interests and government-assisted BC regulation, namely .

Regulatory pattern 1 represents a prevalent evolutionary trajectory characterized by a reactive transformation in scientific research institutions, triggered by the manifestation of research misconduct. This passive regulatory adaptation is marked by inefficiency and protracted processes, resulting in delayed governmental attention to research integrity issues and a lag in the adoption of BC regulation by scientific research institutions. Consequently, this pattern exacerbates the deterioration of research integrity, as evidenced by a continual increase in cases of research misconduct.

Regulatory pattern 2, while initiated by governmental intervention and thus improving the efficiency of the transformation process, still confines scientific research institutions to a passive regulatory role. The transition remains lengthy and does not fundamentally resolve the underlying inefficiencies.

In contrast, regulatory pattern 3 constitutes the optimal evolutionary pathway. Compared to patterns 1 and 2, pattern 3 is distinguished by three key features: (1) Governments effectively implement and publicize targeted BC subsidy policies, thereby fostering a favorable policy environment and maximizing incentives for scientific research institutions to proactively engage in regulatory transformation; (2) regulatory resource allocation is optimized, restoring scientific research institutions to their principal role in research integrity oversight, while governments assume an indirect supervisory function; and (3) the efficiency of regulatory transformation within scientific research institutions is significantly enhanced, curbing the escalation of research misconduct and reducing the incidence of integrity violations.

5. Case and Simulation Analysis

5.1. Case and Parameters Setting

In 2022, Chenzhou City in Hunan Province, China, launched a BC-based research integrity platform. The Chenzhou Science and Technology Bureau, project-recommending entities, entrusted organizations, and relevant regulatory bodies utilize this platform to manage critical project workflows. The platform systematically organizes information on scientific research institutions, project archives, expert databases, and integrity blacklists, and immutably records research integrity data such as project initiation, research, evaluation, acceptance, and performance assessment on-chain throughout the research project lifecycle, thereby generating research integrity metadata. Scientific research institutions, the general public, and peer reviewers can access publicly available on-chain project information for evaluation and oversight, with the results also recorded on-chain for evidentiary purposes.

This reference case demonstrates the feasibility of BC in research integrity management. However, due to limited disclosure in the reference case, obtaining sufficient data for simulation remains challenging. Consequently, this study adopts parameterization methods from the literature [69] and sets parameters according to actual conditions. In accordance with Zhang [70] and Shi et al. [71], the initial values of parameters were set as follows: cost parameters and for researchers were set to 10 and 6, respectively; cost parameters and for research administration authorities were set to 3 and 6, respectively; and cost parameters and for the government were set to 6 and 3, respectively. Specifically following the “Implementation Rules for the National BC Innovation Application Comprehensive Pilot Project in Chengdu” [72] and the “Revised Special Fund Subsidy Measures for BC in Longyan City (2020–2023)” [73], the value range for parameter is set to [10, 200]. Based on the procurement announcement for the BC research platform at Donghua University in Shanghai [74], the initial value for parameter is set at 29.8. Drawing on disciplinary cases from the Chenzhou Science and Technology Bureau [75] and penalty standards from the National Health Commission’s investigations into medical research integrity [76], parameters and are defined in terms of the return of research funds or deductions in monthly performance pay. Following the established literature [77,78,79], the initial value ranges for parameters , , and are set to [1, 4], while parameter is set to [1, 6], and parameters and are set to [0.1, 0.8]. Following the methodology established by Sun et al. [80], parameters and were each initialized with a value of 0.5. Similarly, drawing upon the work of Wang et al. [81], parameters and were also each assigned an initial value of 0.5. For other variables lacking case references or statistical data, random sampling is employed based on the aforementioned empirical context [82]. Table 4 presents the initial parameter values, and Figure 7 illustrates the evolutionary equilibrium simulation results.

Table 4.

Initial value of relevant parameters.

Figure 7.

Simulation diagram of evolutionary equilibrium results of scientific research units’ selection of BC regulation.

5.2. Simulation Analysis of Key Factors Influencing Scientific Research Institutions’ Selection of BC Regulation

5.2.1. Sensitivity Analysis of Important Influencing Factors of Scientific Research Institutions’ Selection of BC Regulation, Based on Prospect Theory

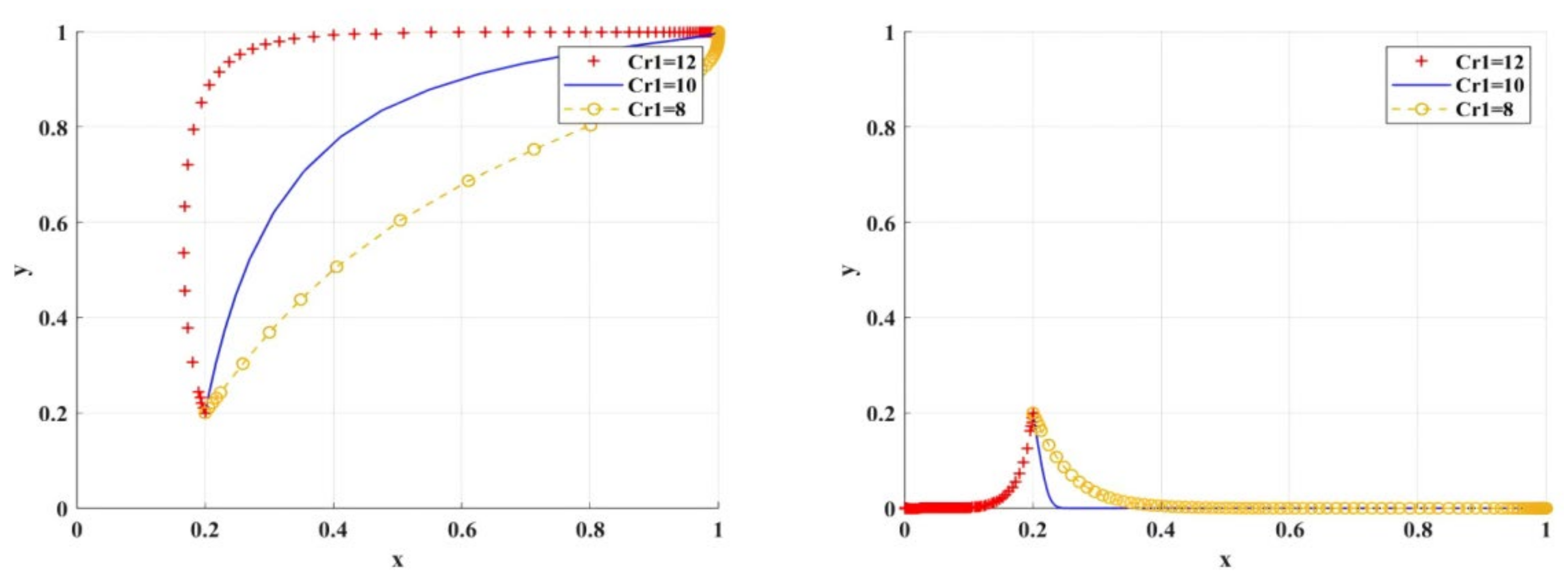

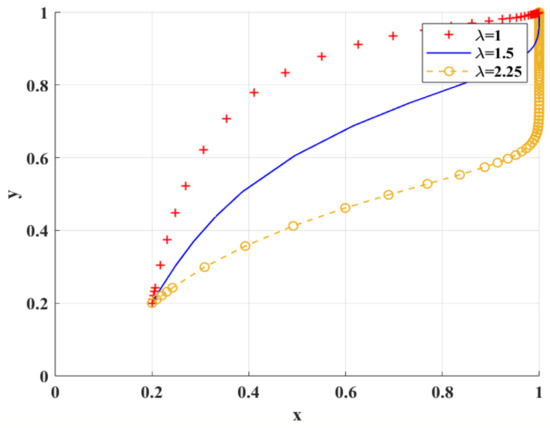

- (i)

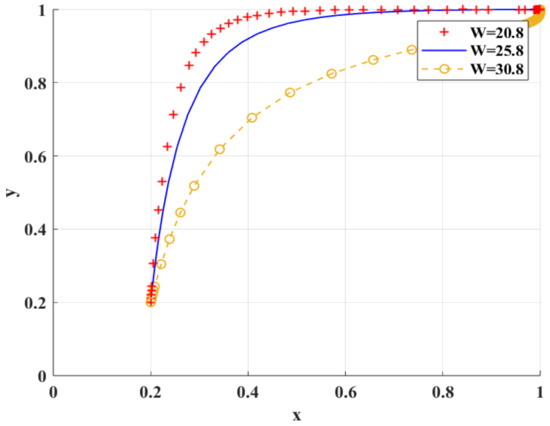

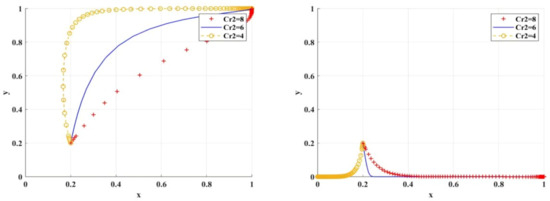

- Sensitivity analysis of loss aversion coefficient

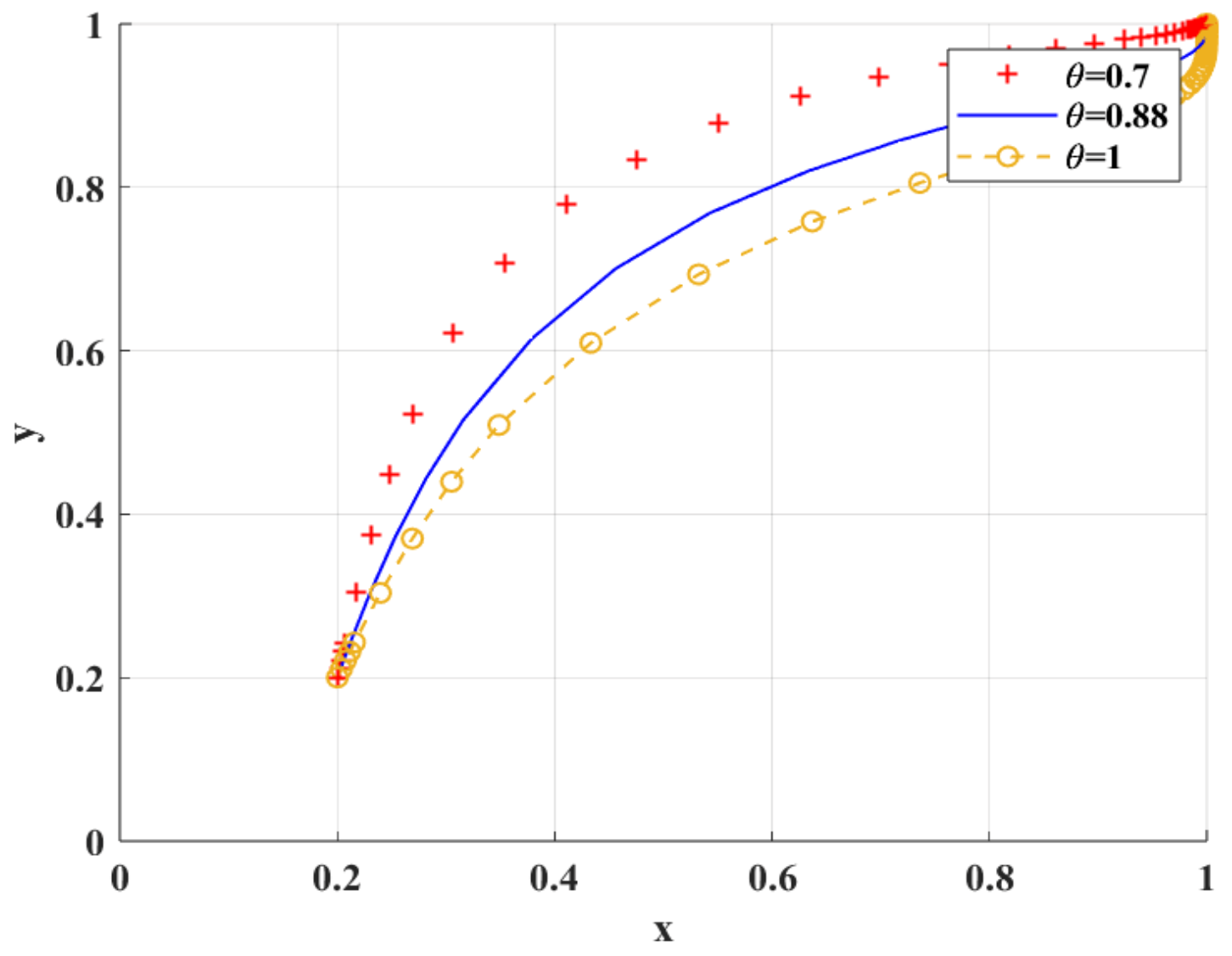

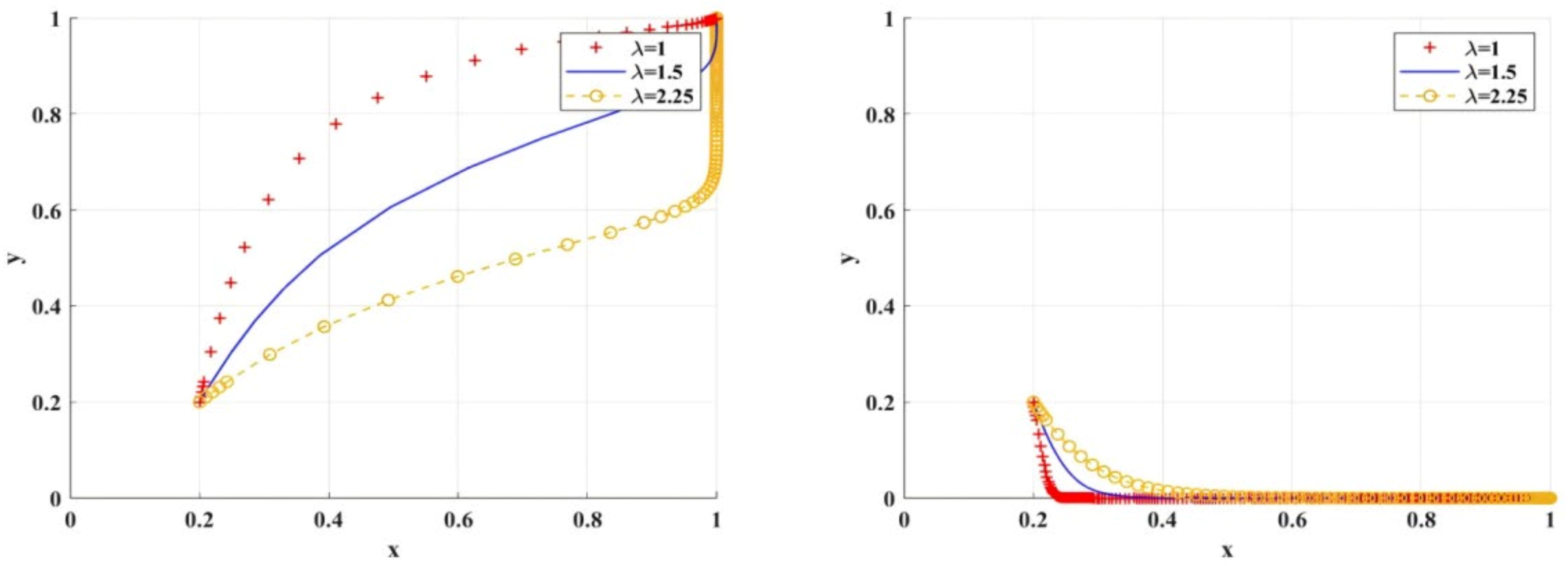

Figure 8 shows the simulation results under the scenario of variable loss aversion coefficient . With the increase in , the degree of researchers’ aversion to the risk of research integrity and loss avoidance increases, which leads to the trend of research integrity. With the decrease in , the speed of researchers’ tendency to engage in research integrity increases only when scientific research institutions tend to adopt BC regulation. With the increase in , the rate at which scientific research institutions tend to adopt BC regulation decreases. This is because scientific research institutions will carefully consider the risks and effects of the new digital supervision technology and delay the time of adopting BC regulation.

Figure 8.

Impact of different loss aversion coefficient values on BC regulation when adopted by scientific research institutions.

- (ii)

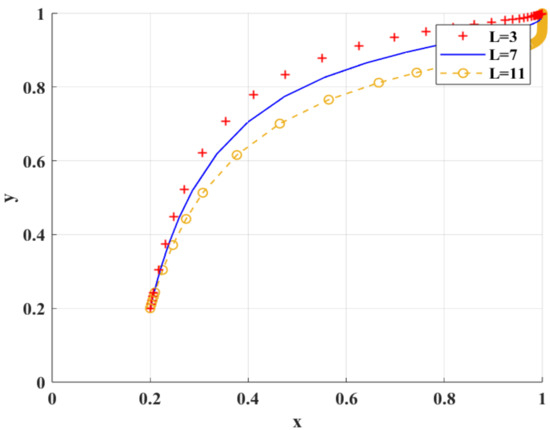

- Sensitivity analysis of risk preference coefficient

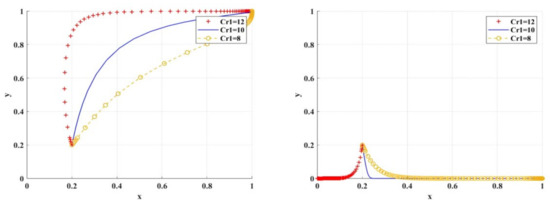

Figure 9 shows the simulation results under the scenario of variable risk preference coefficient . When is smaller, it indicates that the game players are more sensitive to risk preference. With the decrease in , researchers tend to be slower in the probability of research integrity, which indicates that the more risk preference researchers have, the more they tend to select research integrity. Only when scientific research institutions tend to choose BC regulation, can researchers choose research integrity.

Figure 9.

Influence of different risk preference coefficient values on BC regulation when adopted by scientific research institutions.

5.2.2. Sensitivity Analysis of Other Important Influencing Factors for Scientific Research Institutions’ Selection of BC Regulation

Select the loss aversion coefficient and the risk preference coefficient , so that the initial probabilities of and of researchers, scientific research institutions, and governments are all 0.2. Explore other important factors affecting the selection of BC regulation by scientific research institutions.

- (iii)

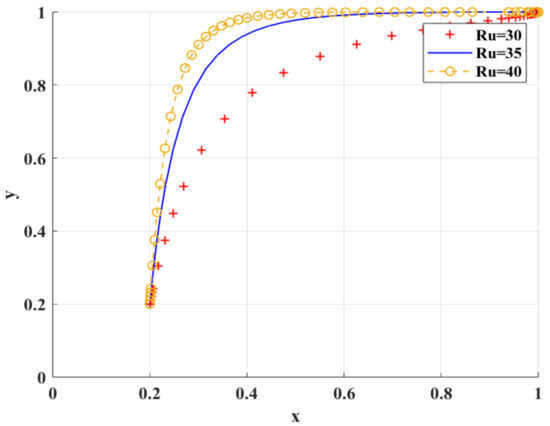

- Sensitivity analysis of government subsidies

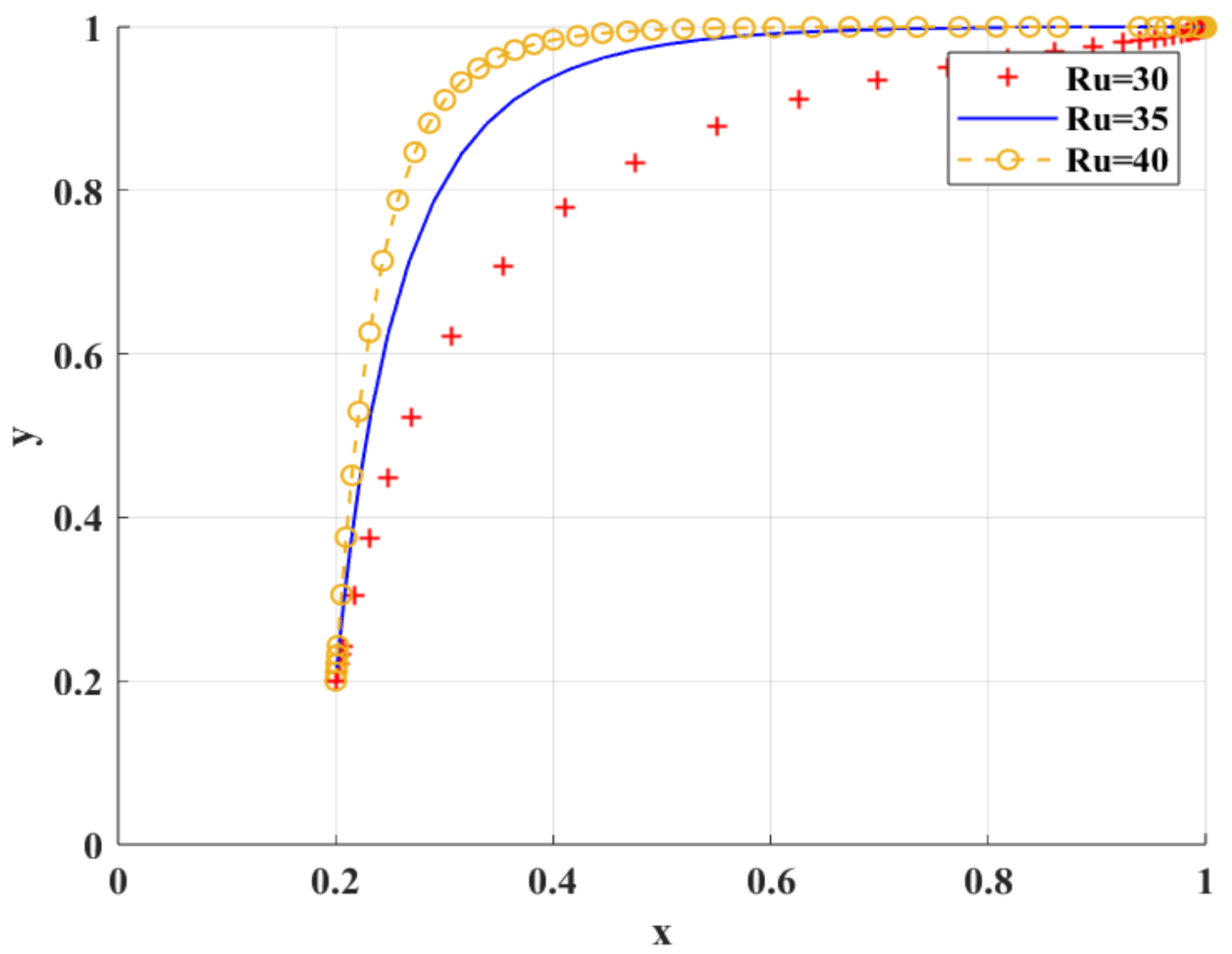

Figure 10 shows the simulation results under the scenario of variable government subsidies. When gradually increases, scientific research institutions are more inclined to BC regulation.

Figure 10.

The impact of on the adoption of BC regulation by scientific research institutions.

- (iv)

- Sensitivity analysis of cost factors

Figure 11 shows the simulation results under the variable scenarios of research integrity cost, research misconduct cost, and psychological deterrent hidden cost. When gradually increases, only when scientific research institutions are more inclined to BC regulation, will researchers have a higher probability of choosing research integrity. This indicates that when is higher, researchers should be constrained to choose research misconduct by strengthening the scientific research institutions’ inclined BC regulation.

Figure 11.

The impact of , , on the adoption of BC regulation by scientific research institutions.

When gradually decreases, only when scientific research institutions are more inclined to the BC regulation, will researchers have a higher probability of choosing research integrity. This indicates that when is low, researchers should be constrained to choose research misconduct by strengthening the scientific research institutions’ inclined BC regulation. Therefore, only by raising the cost of research misconduct can researchers be forced to spontaneously behave in a way that prioritizes research integrity.

When gradually decreases, only when scientific research institutions are more inclined to BC regulation, will researchers have a higher probability of choosing research integrity. This indicates that when is low, researchers should be constrained to choose research integrity by strengthening the scientific research institutions’ inclined BC regulation.

Other costs, such as the sensitivity of the costs of different regulatory strategies of scientific research institutions and governments, have no obvious impact on the adoption of BC regulation by scientific research institutions, and so they are omitted from this study.

Figure 12 shows the simulation results of the scenario of variable construction and daily maintenance costs. negatively affects the adoption of BC regulation by scientific research institutions.

Figure 12.

The impact of on BC regulation when adopted by scientific research institutions.

- (v)

- Sensitivity analysis of privacy disclosure loss

Figure 13 shows the simulation results under the scenario of variable loss of privacy disclosure. The increasing loss of privacy disclosures will affect the evolutionary speed of scientific research institutions’ choice of BC regulation. Only by reducing the loss of data privacy disclosures will scientific research institutions tend to adopt BC regulation.

Figure 13.

The impact of on the adoption of BC regulation by scientific research institutions.

5.3. Comparative Simulation Analysis of BC Regulation Versus Traditional Regulation in Scientific Research Institutions

In order to verify the effectiveness of BC-enabled scientific research institutions’ scientific research credit supervision, this study compares the simulation results of two kinds of supervision strategies of scientific research institutions. The above Table 4 shows the simulation data of scientific research institutions using BC regulation, and Table 5 shows the simulation data of scientific research institutions using traditional regulation. Based on the value ranges assigned in Table 4 and in accordance with the formation conditions of different equilibrium points in the evolutionary game model, the data for Table 5 are derived. The simulation diagrams corresponding to the data in Table 5 are provided in Appendix A.

Table 5.

Initial values of relevant parameters.

5.3.1. Comparative Analysis of Sensitivity of Important Influencing Factors of Different Strategic Choices of Scientific Research Institutions, Based on Prospect Theory

- (i)

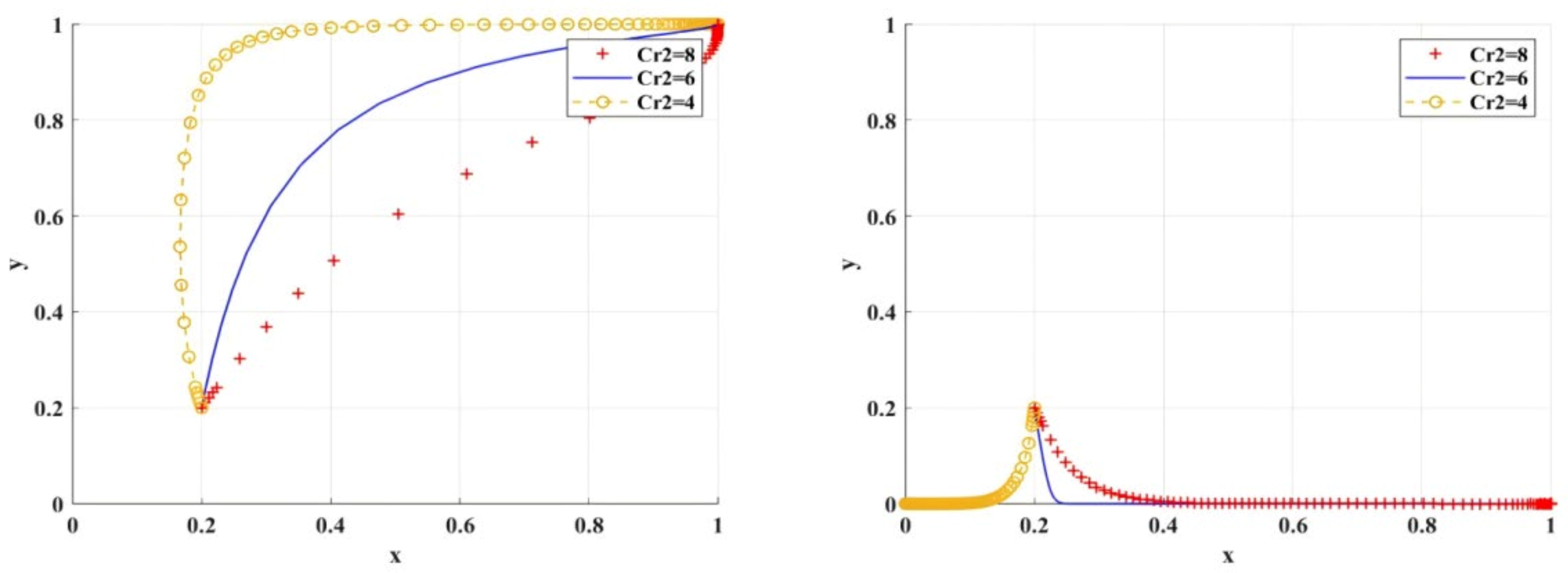

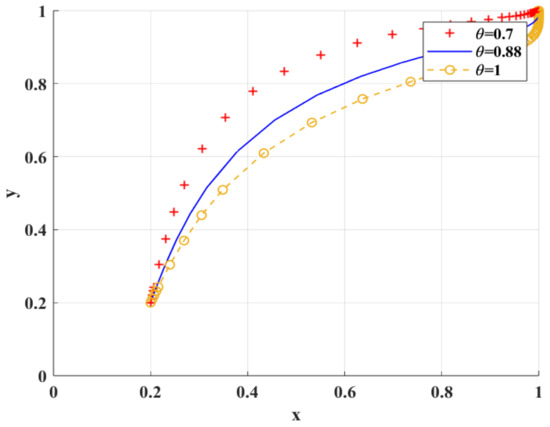

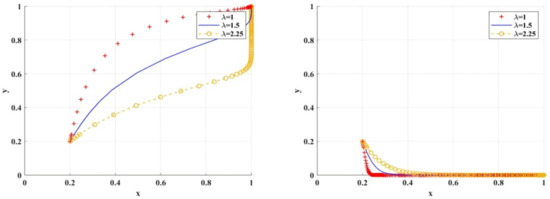

- Comparative analysis of sensitivity of loss aversion coefficient

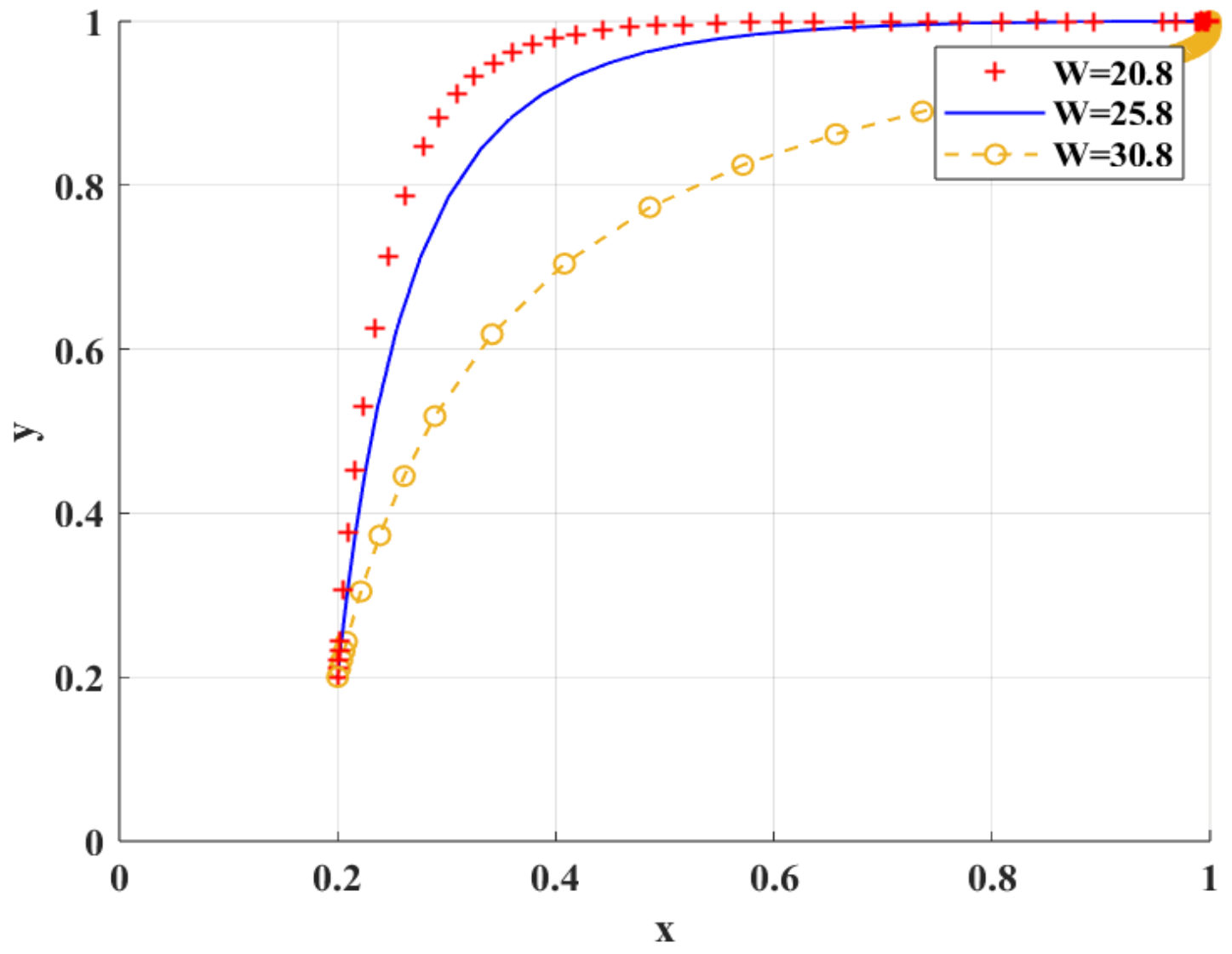

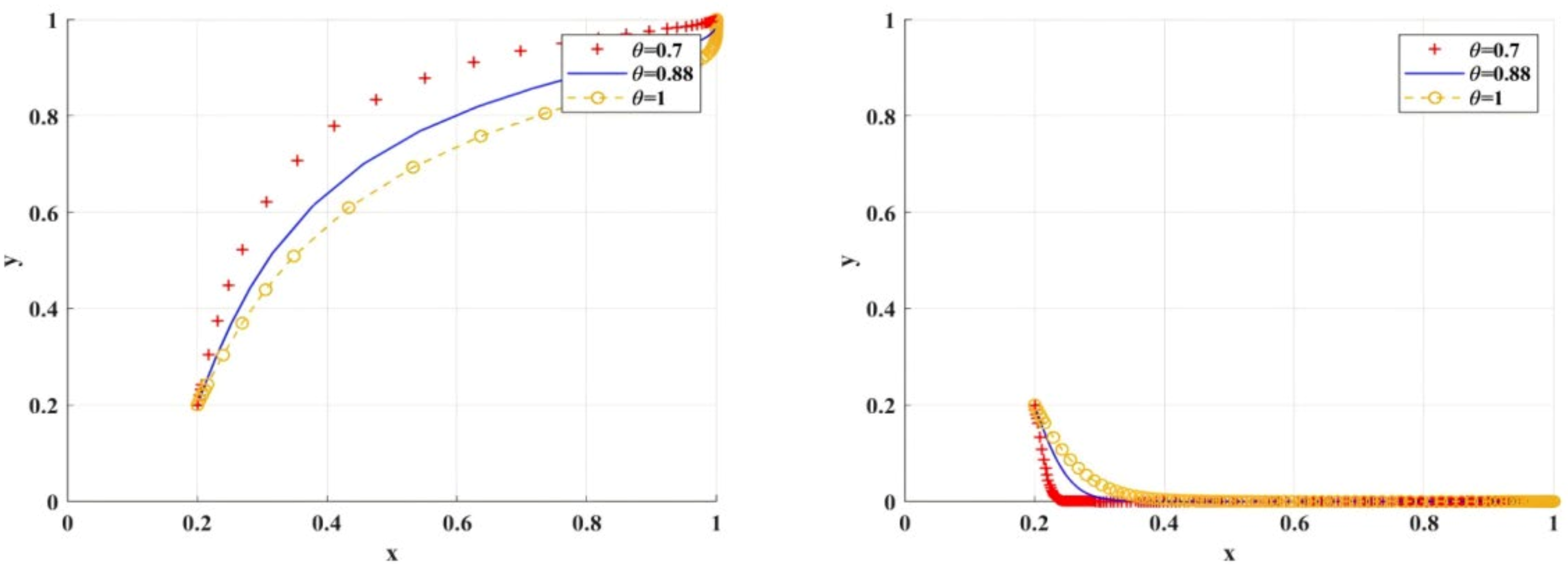

Figure 14 shows the simulation results of the variable scenario of loss aversion coefficient . First, with the increase of , the speed of scientific research institutions’ adoption of BC regulation will be delayed, while the impact on scientific research institutions’ adoption of traditional regulation will not change significantly; Second, no matter how changes, there is a positive linear relationship between the adoption of BC regulation by scientific research institutions and the choice of research integrity by researchers, and an inverted “” linear relationship between the adoption of BC regulation by scientific research institutions and the choice of research integrity strategy by researchers, which indicates that the adoption of BC regulation by scientific research institutions has a deterrent effect on researchers, that is, scientific research institutions’ preference for BC regulation will promote researchers’ choice of research integrity. Specifically, at the same level of parameter , the adoption of BC regulation by scientific research institutions accelerates the rate at which researchers shift toward research integrity, compared to traditional regulation. On the contrary, even if scientific research institutions adopt traditional regulation, researchers do not immediately choose to uphold research integrity, but embrace this mentality over time.

Figure 14.

Impact of different loss aversion coefficient values on BC regulation/traditional regulation of scientific research institutions.

- (ii)

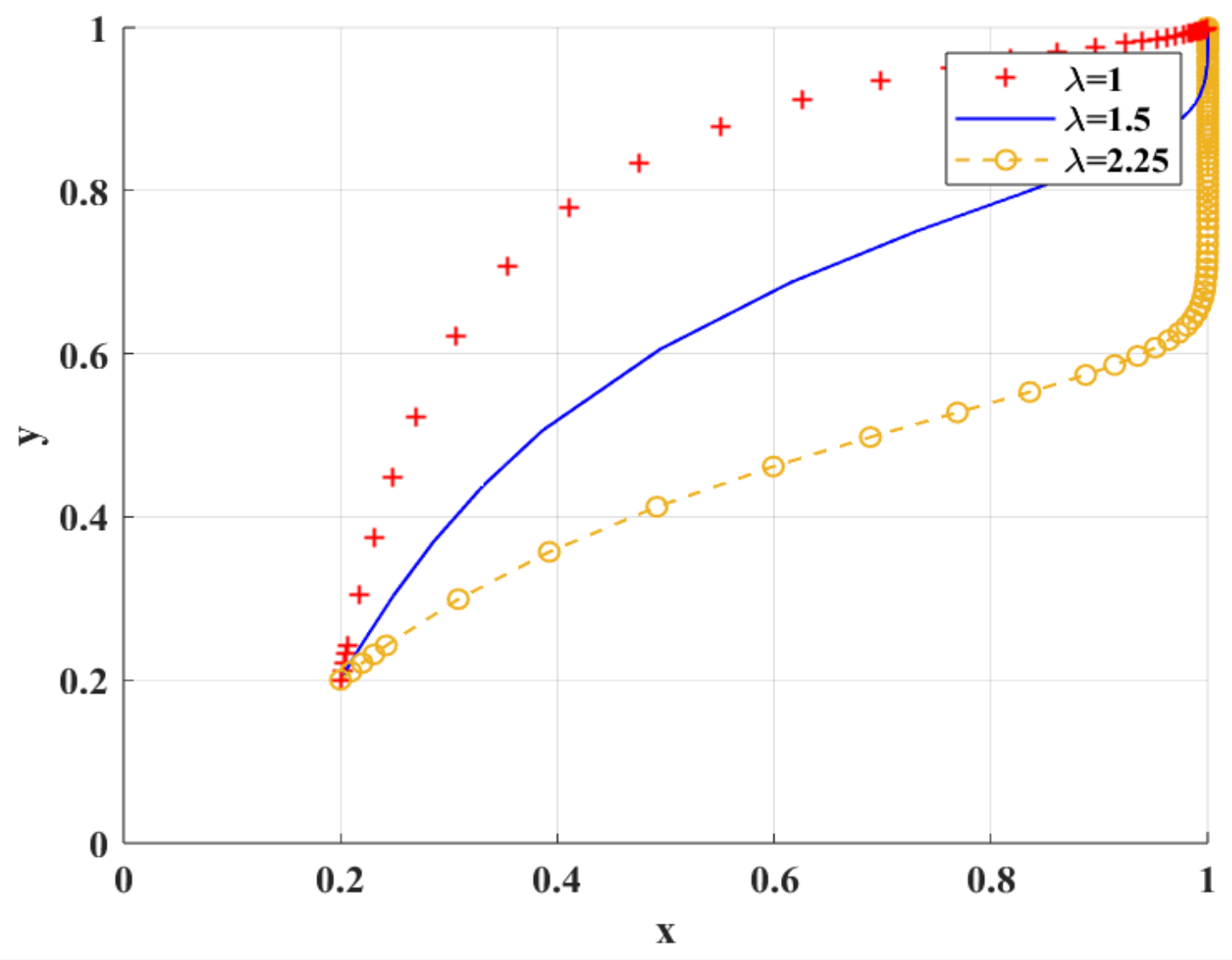

- Comparative analysis of sensitivity of risk preference coefficient

Figure 15 shows the simulation results of the variable scenario of risk preference coefficient . As decreases, researchers tend to research integrity more slowly. Compared with traditional regulation, the effect of using BC regulation to promote researchers to choose research integrity is better. When , the probability of researchers choosing research integrity eventually evolves to about 0.96. In addition, with the same loss aversion coefficient , when compared with traditional regulation, BC regulation adopted by scientific research institutions has a deterrent effect on researchers, and can better promote researchers to choose research integrity.

Figure 15.

Influence of different risk preference coefficient values on BC regulation/traditional regulation of scientific research institutions.

5.3.2. Comparative Analysis on Sensitivity of Other Important Influencing Factors of Different Strategies for Scientific Research Institutions

Select the loss aversion coefficient and the risk preference coefficient , so that the initial probabilities of and of researchers, scientific research institutions and governments are all 0.2, and explore the impact of other important factors on different strategic choices of scientific research institutions.

- (iii)

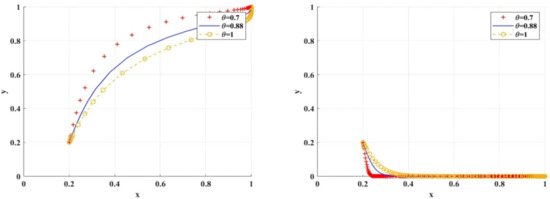

- Sensitivity analysis of traditional regulation characteristics

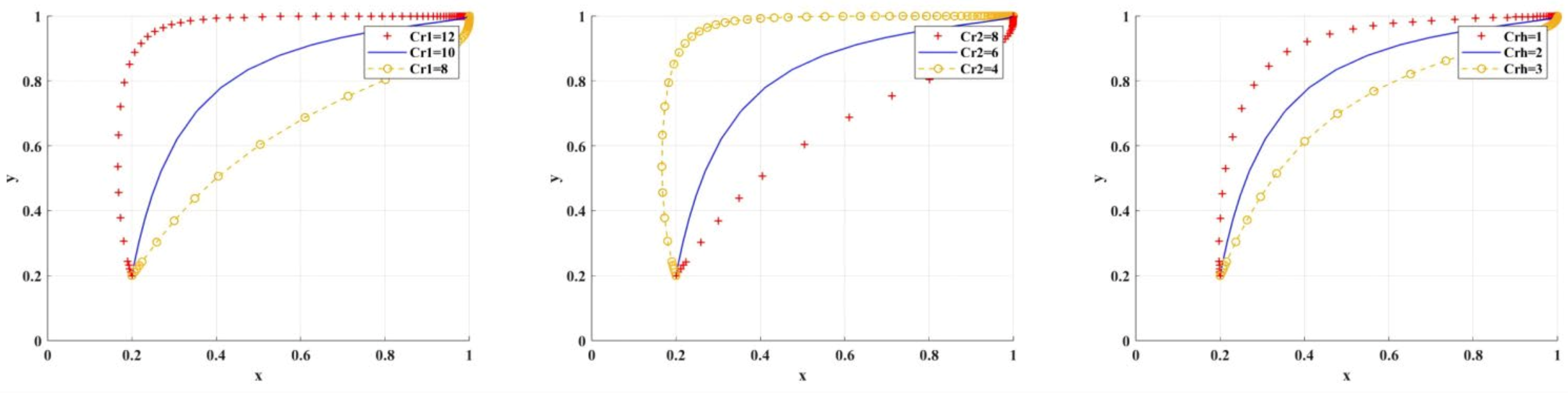

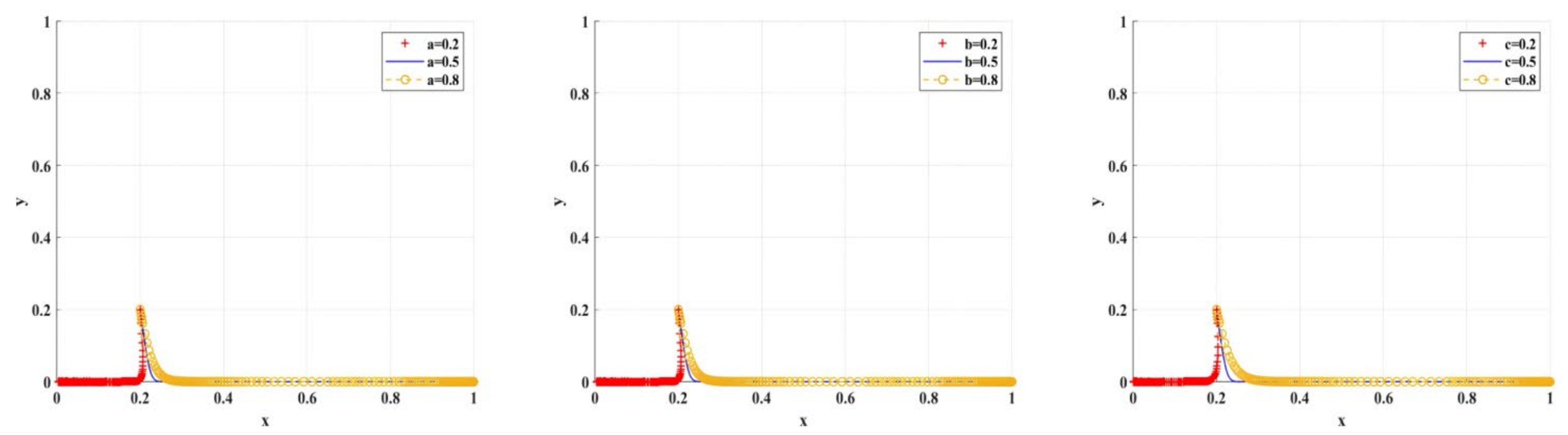

Figure 16 shows the simulation results under the variable situation of the human relationship punishment coefficient, the probability of identifying research misconduct, and the probability of exposing research misconduct. When is low, the slight punishment from scientific research institutions will cause researchers to choose research misconduct. Only when increases to 0.5 or above, will researchers tend to adopt research integrity.

Figure 16.

The impact of , , on BC regulation/traditional regulation of scientific research institutions.

When is low, researchers choose research misconduct; when increases to 0.5 or above, researchers tend to embrace research integrity.

When is low, researchers choose research misconduct; when increases to 0.5 or above, researchers tend to embrace research integrity.

- (iv)

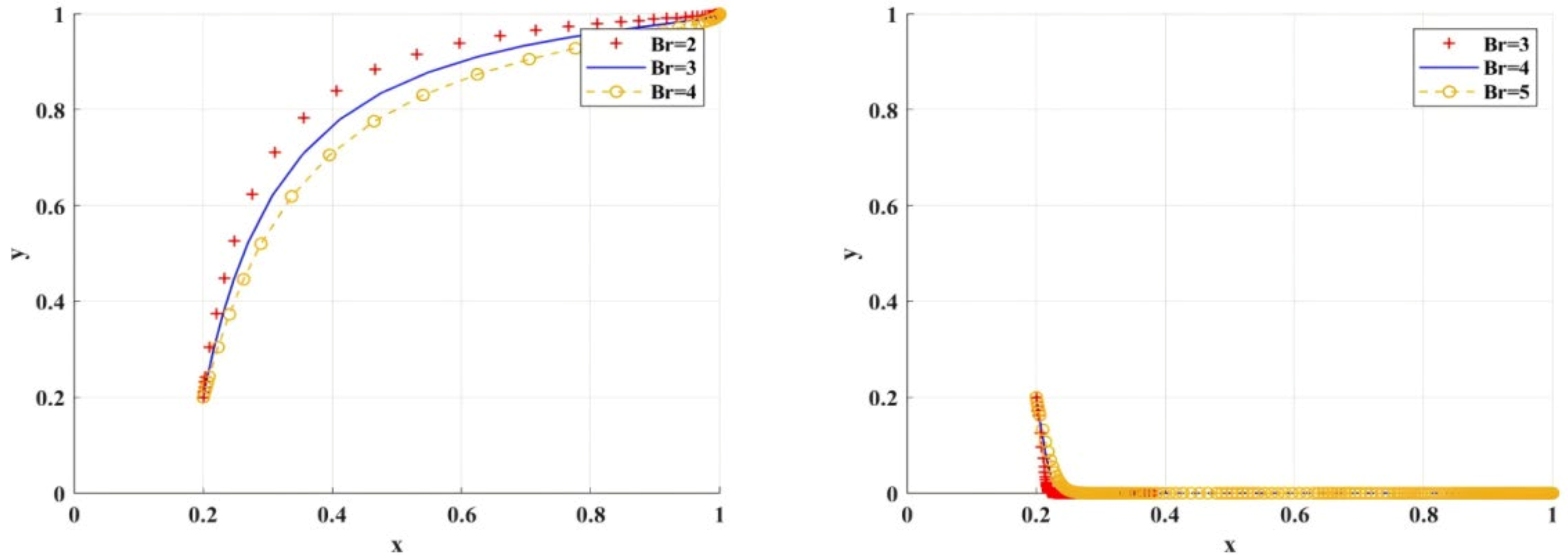

- Comparative analysis of sensitivity of cost factors

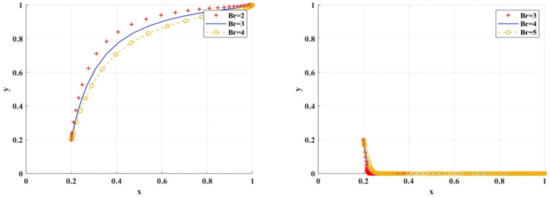

Figure 17 shows the simulation results under the scenario of variable cost of research integrity. When is at the same level, different regulatory strategies of scientific research institutions have different effects on researchers’ choices regarding research integrity. When is at the lower middle level, different regulatory strategies of scientific research institutions can encourage researchers to choose research integrity. When increases to 12 or more, scientific research institutions only choose BC regulation, encouraging researchers to choose research integrity.

Figure 17.

The impact of on BC regulation/traditional regulation of scientific research institutions.

Figure 18 shows the simulation results under the scenario of variable research misconduct costs. is at a medium to high level. Different regulatory strategies of scientific research institutions can encourage researchers to choose research integrity. When is reduced to 4 or less, scientific research institutions only choose BC regulation, and this encourages researchers to choose research integrity.

Figure 18.

The impact of on BC regulation/traditional regulation of scientific research institutions.

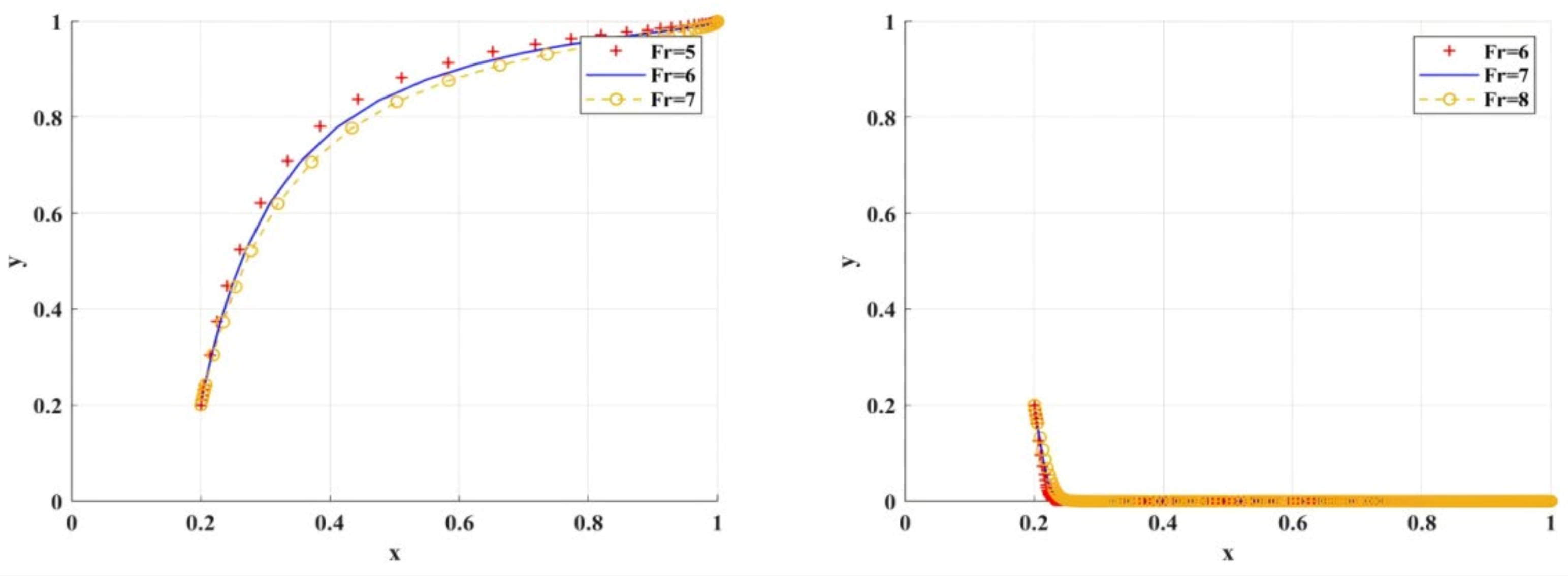

- (v)

- Comparative analysis of reputation loss and penalty sensitivity

Figure 19 shows the simulation results under the situation of variable reputation loss. The adoption of BC regulation by scientific research institutions can better promote researchers to choose research integrity when is reduced. In contrast, scientific research institutions adopt traditional regulation. Only when is increased can researchers choose research integrity.

Figure 19.

The impact of on BC regulation/traditional regulation of scientific research institutions.

Figure 20 shows the simulation results of a variable scenario in which researchers choose to be punished by scientific research institutions for research misconduct. BC regulation adopted by scientific research institutions can better encourage the researchers to choose research integrity under the condition of reducing . in contrast, traditional regulation adopted by scientific research institutions can only promote researchers to choose research integrity under the condition of improving .

Figure 20.

The impact of on BC regulation/traditional regulation of scientific research institutions.

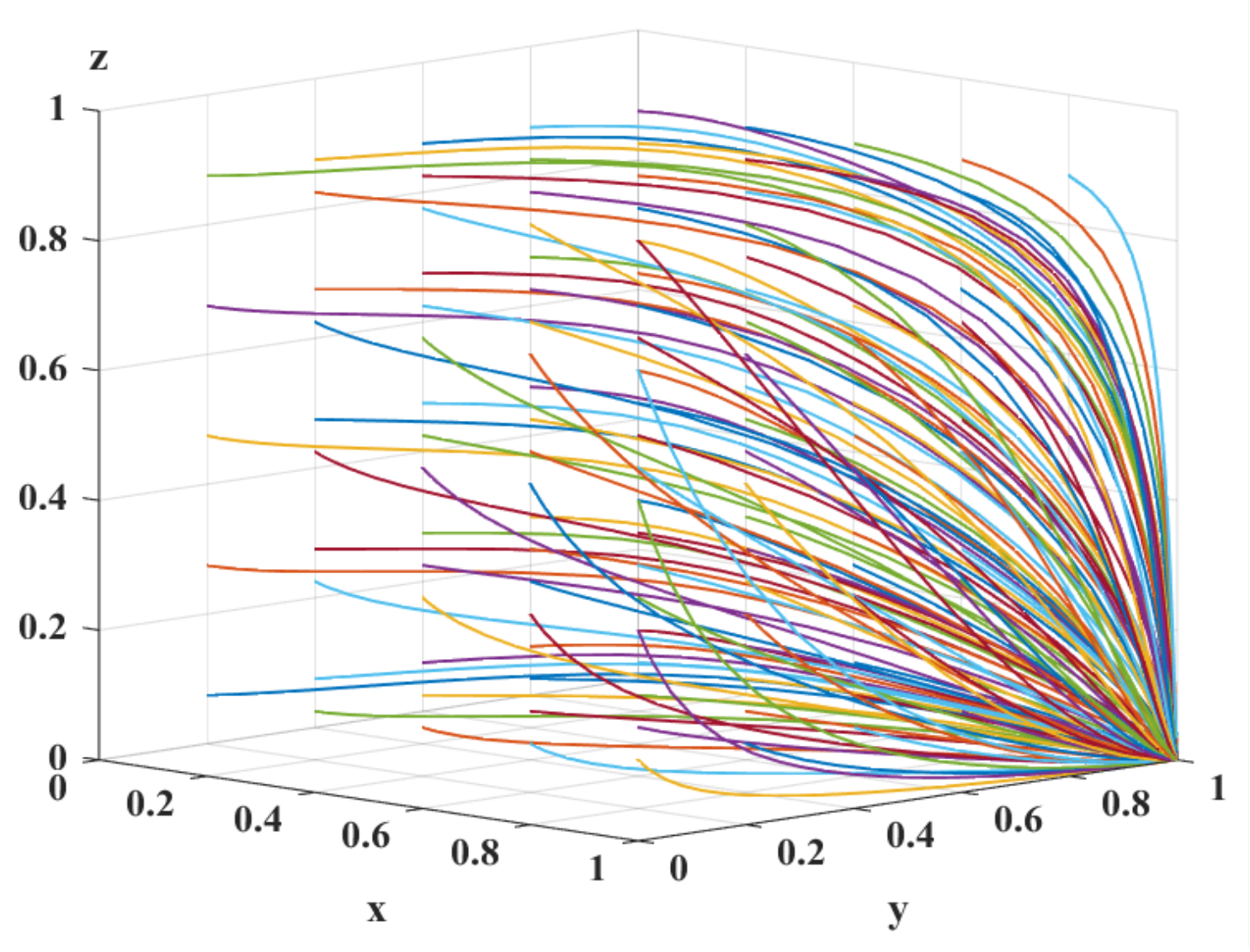

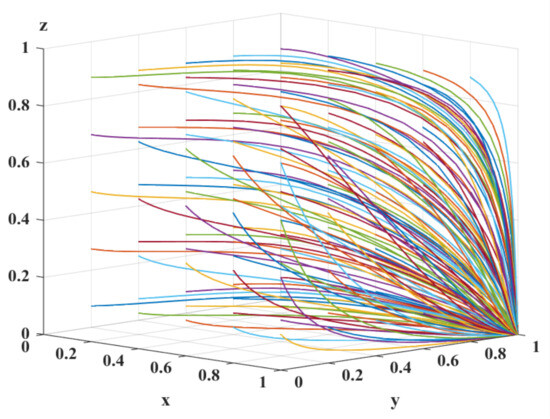

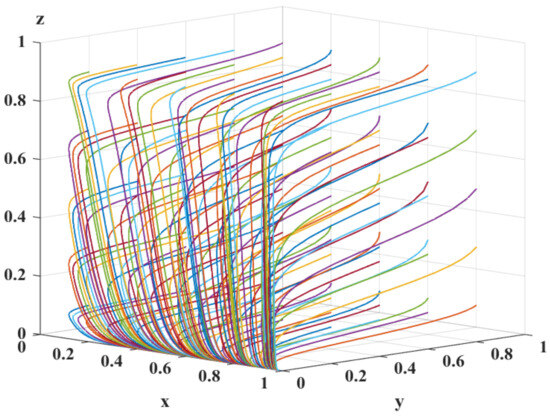

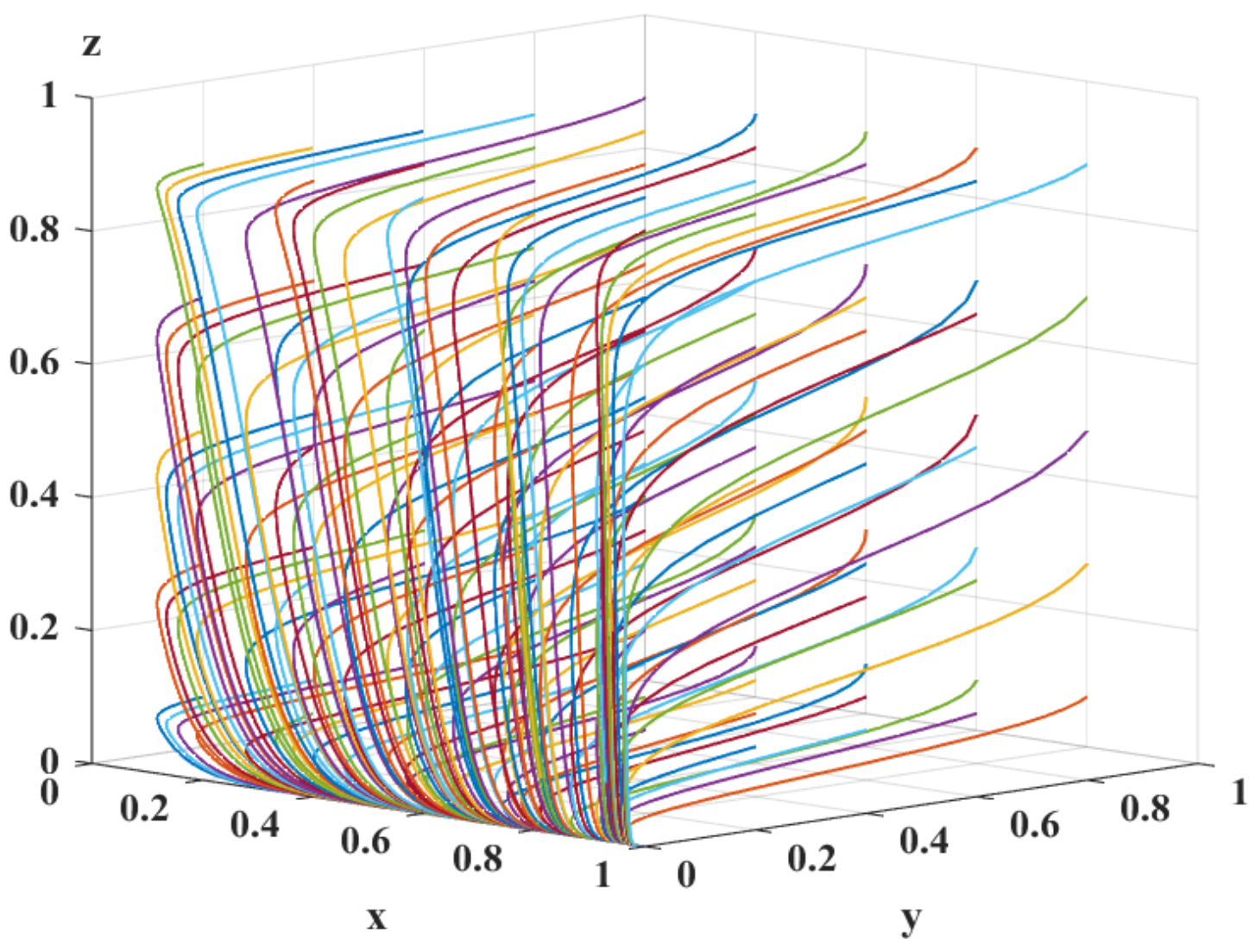

5.4. Simulation Analysis of the Evolutionary Pathways in BC-Enabled Research Integrity Regulation Patterns for Scientific Research Institutions

Combined with the contents of propositions 4–7 in Section 4 of this study, the evolutionary process of scientific research credit regulation of BC-enabled scientific research institutions presents three evolutionary patterns: the passive regulation pattern with the result of scientific research misconduct as the trigger point, the passive regulation pattern with governments as the trigger point, and the active regulation pattern driven by the result of research integrity. See Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9 for the values of relevant parameters. Based on the value ranges assigned in Table 4 and in accordance with the formation conditions of different equilibrium points in the evolutionary game model, the data for Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9 were generated. The data simulation diagrams are provided in Appendix B. The path simulation of the evolution of scientific research credit supervision pattern of BC-enabled scientific research institutions is shown in Figure 21.

Table 6.

: Initial values of relevant parameters.

Table 7.

: Initial values of relevant parameters.

Table 8.

: Initial values of relevant parameters.

Table 9.

: Initial values of relevant parameters.

Figure 21.

The evolutionary path of scientific research credit supervision pattern of BC-enabled scientific research institutions.

6. Conclusions

Based on prospect theory, this study establishes a tripartite evolutionary game model to examine research credit supervision empowered by BC, involving researchers, scientific research institutions, and governments.

This study yields the following main conclusions:

- (i)

- Under equivalent levels of cost, reputation loss, and penalty settings, the BC-based supervision model achieves higher regulatory effectiveness compared to traditional strategies.

- (ii)

- Beyond cost and government subsidies, risk aversion coefficients, risk preference coefficients, and privacy breach losses are key factors influencing scientific research institutions’ adoption of BC supervision.

- (iii)

- The evolutionary pathways of BC-enabled research credit supervision comprise three modes: a passive regulatory framework triggered by instances of research misconduct (Path 1), a passive regulatory paradigm triggered by government-led initiatives (Path 2), and an active regulatory pattern driven by research integrity outcomes (Path 3). This study further offers managerial insights into transitioning from Path 1 to Path 3.

- (iv)

- An analysis grounded in prospect theory reveals that research integrity is only effectively ensured when scientific research institutions implement BC-based supervision, particularly in contexts involving high-risk-seeking researchers. Furthermore, the BC-based regulatory approach demonstrates a consistently stronger deterrent effect than conventional methods across varying risk attitudes, thereby more reliably promoting research integrity.

This study suggests that researchers should enhance their cognitive sensitivity to research integrity and the consequences of misconduct, and strengthen their capacity to monitor and expose unethical practices. Firstly, it is essential to reinforce awareness of research integrity and recognize that the long-term losses incurred by misconduct far exceed any short-term gains. Secondly, researchers should familiarize themselves with the channels and procedures for reporting research misconduct, actively participate in oversight procedures, and take the initiative to report violations. Thirdly, relevant scientific research institutions should strengthen guidance on research values, appropriately improve compensation packages, and foster an institutional environment conducive to dedicated research, thereby curbing the tendency toward excessive pursuit of quick results.

This study suggests that scientific research institutions can enhance their willingness to adopt BC-based supervision strategies through considerations of risk perception, cost control, and comprehensive benefits. Firstly, internal advocacy should be strengthened to improve understanding of the feasibility and importance of BC in research credit supervision. This not only helps internally drive the willingness to adopt BC but also exerts a deterrent effect on researchers, encouraging compliance with integrity norms. Secondly, active communication with BC providers should be conducted to effectively reduce the construction and daily operational costs of BC systems. Thirdly, in addition to government subsidies, measures such as increasing penalties for research misconduct can be implemented to broaden revenue sources, offset the costs of BC adoption, and further strengthen the willingness to adopt the technology. Simultaneously, continuous collaboration with providers to optimize BC anti-leakage mechanisms will enhance system security levels, mitigate privacy leakage risks, and thereby increase adoption willingness.

This study proposes that governments should foster the willingness of research administration authorities to adopt BC-based supervision strategies by implementing the following supporting measures. Firstly, they should formulate policies to promote the application of BC in research credit supervision, and enhance advocacy and guidance to stimulate the endogenous motivation of scientific research institutions. Simultaneously, close attention should be paid to the difficulties and challenges encountered during implementation. “Targeted subsidies” should be provided based on actual funding gaps, offering differentiated financial support to avoid a “one-size-fits-all” approach. This will improve policy implementation efficiency while alleviating fiscal pressure. Secondly, industrial policies that promote the development of BC should be introduced to facilitate technological maturity and scenario application. Such measures will not only help BC providers develop more secure and efficient solutions but also create a favorable environment for collaboration between scientific research institutions and providers. This will establish a virtuous cycle of “technological advancement–expanded application–enhanced willingness.” Thirdly, there should be a strengthened service orientation, avoiding mere formalism. Within the framework of safeguarding the bottom line of research integrity supervision, scientific research institutions and researchers should be granted sufficient autonomy. Administrative intervention should be applied prudently to better foster research integrity awareness and willingness to adopt BC.

Further research in the future can be expanded as follows: First, this study constructs a three-party game model of scientific research credit supervision of scientific research institutions enabled by BC, and only considers the impact of static punishment mechanisms on scientific research credit supervision of scientific research institutions. In the future, dynamic punishment mechanisms and dynamic incentive mechanisms can be considered to explore the impact of dynamic punishment or dynamic incentive mechanisms on scientific research credit supervision of scientific research institutions. Second, this study only considers the game analysis of the tripartite main body of the scientific research credit supervision link of scientific research institutions empowered by the BC. In the future, scientific research institutions can use the process link of the BC, introduce the BC supplier, build the four-party game model of researchers–scientific research institutions–governments–BC supplier, and analyze the impact of the BC supplier’s improvement of the BC on the scientific research credit supervision of scientific research institutions. Third, it would be promising to adopt the Generalized Optimal Game Theory [83,84] and Computer-Generated Force [84,85] to establish a tripartite coordination system. This system would synthesize subjective perception, objective existence, and computational complexity to analyze the mechanisms and models of research credit supervision by overseeing entities empowered by BC under a regulatory framework. Fourth, AI-powered audit systems could be adopted to empower research supervisory authorities in conducting scientific research credit oversight. Finally, this study does not fully account for geopolitical factors. Future research could incorporate cross-national comparative case studies to further validate the generalizability of the findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.L.; methodology, Z.Z.; validation, Z.Z.; formal analysis, R.C.; data curation, Z.Z.; writing—original draft, Z.Z. and M.Z.; writing—review and editing, R.C.; project administration, G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Henan University Philosophy and Social Science Innovation Team Funding Project (2020-CXTD-12; 2024-CXTD-10) and Ministry of Education Humanities and Social Sciences Youth Fund Project (22YJC630002).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Initial values of relevant parameters.

Table A1.

Initial values of relevant parameters.

| Parameter | Initial Value | Parameter | Initial Value | Parameter | Initial Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 3 | 3 | |||

| 10 | 4 | 0.5 | |||

| 6 | 7 | 0.5 | |||

| 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |||

| 3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |||

| 6 | 2 | 1 | |||

| 29.8 | 3 | 0.7 | |||

| 6 | 1 | — | — |

Figure A1.

Simulation results of the evolutionary equilibrium.

Figure A1.

Simulation results of the evolutionary equilibrium.

Appendix B

Table A2.

: Initial values of relevant parameters.

Table A2.

: Initial values of relevant parameters.

| Parameter | Initial Value | Parameter | Initial Value | Parameter | Initial Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3 | 3 | |||

| 10 | 1 | 0.5 | |||

| 6 | 1 | 0.5 | |||

| 3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |||

| 3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |||

| 6 | 2 | 1 | |||

| 29.8 | 0 | 0.7 | |||

| 6 | 1 | — | — |

Figure A2.

Simulation results of the evolutionary equilibrium.

Figure A2.

Simulation results of the evolutionary equilibrium.

Table A3.

: Initial values of relevant parameters.

Table A3.

: Initial values of relevant parameters.

| Parameter | Initial Value | Parameter | Initial Value | Parameter | Initial Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 3 | 3 | |||

| 10 | 4 | 0.5 | |||

| 6 | 7 | 0.5 | |||

| 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |||

| 3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |||

| 6 | 2 | 1 | |||

| 29.8 | 3 | 0.7 | |||

| 6 | 1 | — | — |

Figure A3.

Simulation results of the evolutionary equilibrium.

Figure A3.

Simulation results of the evolutionary equilibrium.

Table A4.

: Initial values of relevant parameters.

Table A4.

: Initial values of relevant parameters.

| Parameter | Initial Value | Parameter | Initial Value | Parameter | Initial Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 3 | 3 | |||

| 10 | 4 | 0.5 | |||

| 6 | 7 | 0.5 | |||

| 2 | 0.2 | 0.5 | |||

| 3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | |||

| 6 | 2 | 1 | |||

| 29.8 | 9 | 0.7 | |||

| 6 | 1 | — | — |

Figure A4.

Simulation results of the evolutionary equilibrium.

Figure A4.

Simulation results of the evolutionary equilibrium.

Table A5.

: Initial values of relevant parameters.

Table A5.

: Initial values of relevant parameters.

| Parameter | Initial Value | Parameter | Initial Value | Parameter | Initial Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 3 | 3 | |||

| 10 | 3 | 0.5 | |||

| 6 | 6 | 0.5 | |||

| 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |||

| 3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |||

| 6 | 2 | 1 | |||

| 29.8 | 3 | 0.7 | |||

| 6 | 1 | — | — |

Figure A5.

Simulation results of the evolutionary equilibrium.

Figure A5.

Simulation results of the evolutionary equilibrium.

References

- Edwards, M.A.; Roy, S. Academic Research in the 21st Century: Maintaining Scientific Integrity in a Climate of Perverse Incentives and Hypercompetition. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2017, 34, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L. Five Ways China must Cultivate Research Integrity. Nature 2019, 575, 589–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.L.; Pan, Y.T. The Dilemmas and the Irrational Risks of Measuring Scientific Research Integrity: A Theoretical Reflection on the Technical Approaches to the External Norms of Scientific Research Integrity. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2023, 40, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Wang, K.; Kong, Y. Prevalence of Research Misconduct and Questionable Research Practices: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2021, 27, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ALLEA. The European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity. Available online: https://www.allea.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/ALLEA-European-Code-of-Conduct-for-Research-Integrity-2017-1.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2017).

- Oransky, I. Retractions are Increasing, but not Enough. Nature 2022, 608, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Noorden, R. More than 10,000 Research Papers were Retracted in 2023—A New Record. Nature 2023, 624, 479–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of Science Quality and Integrity. A Framework for Federal Scientific Integrity Policy and Practice. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/media/files/a-framework-federal-scientific-integrity-policy-and-practice (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- National Natural Science Foundation of China. Notification of the Outcomes of Misconduct Cases (First Batch) by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. Available online: https://www.nsfc.gov.cn/publish/portal0/jd/04/info92362.htm (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- National Natural Science Foundation of China. Notification of the Outcomes of Misconduct Cases (First Batch) by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. Available online: https://www.nsfc.gov.cn/publish/portal0/jd/04/info93663.htm (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- National Natural Science Foundation of China. Case Report (2025, Issue No. 1). Available online: https://www.nsfc.gov.cn/publish/portal0/jd/04/info94739.htm (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Wei, H.A.; Wei, B. The Holistic Governance of Integrity in Research. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2019, 36, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H. Technique “Carries Tao”: On Research Integrity Construction Based on Blockchain Technology. Stud. Dialect. Nat. 2021, 37, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, K.L.; Zhang, B.H.; Chen, F.R. Rsearch on the Punishment Intensity of Scientific Research Misconduct in Academic Institutions. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2021, 39, 1345–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaqtari, F.A. The Role of IT Governance in the Integration of AI in Accounting and Auditing Operations. Economies 2024, 12, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Goel, S. Making It Possible for the Auditing of AI: A Systematic Review of AI Audits and AI Auditability. Inf. Syst. Front. 2025, 27, 1121–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, P.C.; Kumar, V.; Lu, T.C.; Daim, T. Technology Convergence Assessment: Case of Blockchain within the IR 4.0 Platform. Technol. Soc. 2021, 67, 101709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secinaro, S.; Dal Mas, F.; Brescia, V.; Calandra, D. Blockchain in the Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Fields: A Bibliometric and Coding Analysis. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2022, 35, 168–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, V. On the Use of Blockchain-based Mechanisms to Tackle Academic Misconduct. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 103805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas-Quispe, M.A.; Pacheco, A. Blockchain Ensuring Academic Integrity with a Degree Verification Prototype. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, H.; Zhong, H.Y. Evolution Analysis of Blockchain Technology Investment Based the Quality and Safety of Agricultural Supply Chain. Oper. Res. Manag. Sci. 2023, 32, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.W.; Xu, X.H.; Guan, X.; Bo, Q.G.; Chen, C. Evolutionary Game Analysis for Blockchain Adoption Decisions of Two Oligopolies in An Agricultural Market. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2024, 33, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; He, D.Y.; Su, H.L. Application of Blockchain Technology to Preventing Supply Chain Finance Based on Evolutionary Game. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2024, 32, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]