1. Introduction

The efficiency of hydraulic drive systems largely depends on the method of the velocity regulation of the hydraulic motors (cylinders). There are two main methods of the velocity regulation, throttle and volumetric [

1]. The first is based on the introduction of a variable hydraulic resistance (throttle valve, two-way or three-way flow control valve), which determines the flow rate supplied to the executive hydraulic drive motor, and the excess flow rate is separated through the main pressure-relief valve. This method of regulation has both advantages and disadvantages. The advantages are a high response performance, the ability to regulate low velocity, relatively inexpensive implementation, and easy automation. However, the general disadvantage is the large hydraulic losses, which lead to large energy losses. The second method of regulation is based on the use of a variable-displacement pump. In this way, by changing the displacement volume (at constant rotation frequency) of the pump (according to a certain control law) as much flow rate as is necessary is supplied to the executive hydraulic cylinder or motor. This leads to high energy efficiency, but there are also some disadvantages: the high cost of the pump, lower response performance (when changing the displacement volume and susceptibility to changes in the external load acting on the driven hydraulic motor) at low velocity [

2]. This makes volumetric regulation suitable for hydraulic drive systems with relatively higher power (over 4 kW).

It is not uncommon for systems with higher requirements to use a combination of the two described methods. A more modern method for dealing with the disadvantages of the two classical methods described is load sensitivity, which in turn is also associated with the use of a variable-displacement pump. The dominant factor in determining the overall efficiency of the system is the pump control performance. The most widely used in high power drives with load sensing are axial-piston pumps. The classic controllers are hydromechanical and they are allowed control according to different laws for regulating the flow rate, pressure, or power [

3,

4]. In mobile applications, designs of axial-piston pumps are used that allow operation in a closed circulation (hydrostatic transmission), and the controllers in them have more varieties. In industrial applications, systems with so-called secondary control [

5] are more often used instead of hydrostatic transmission. Regardless of the industrial or mobile application, one of the ways to improve the control performance and energy efficiency is to replace the classic hydromechanical controller of the pump with an electro-hydraulic proportional valve [

6]. On the one hand, this allows for feedback control not only by load but also by velocity. On the other hand, different types and complexities of control laws apply [

7,

8,

9]. The controllers are digitally embedded in the programmable platforms [

10,

11]. Moreover, they can work in real time [

12]. This motivates a number of researchers carrying out scientific and applied activities to seek synergy between modern control algorithms and electro-hydraulic control devices, especially for axial-piston pumps. This is evidenced by a number of developments with various advanced control algorithms such as linear-quadratic regulator (LQR), H-infinity, and μ [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Unlike conventional PID controllers [

12], the advanced controller allows for higher-control performance [

26]. However, the disadvantages are a more adequate mathematical model, complex synthesis, and the required larger computational resources. In this respect, the use of an adaptive controller allows a balance between a relatively easier synthesis and the need for a relatively small computational resource. Given the variation in the value and direction of the external load on the hydraulic motors, the use of adaptive control laws is appropriate [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37].

This motivates the authors to investigate different classical and advanced control algorithms, which can be synthesized and tested both in simulation and experimental conditions.

The main goal of this article is to present the synthesis, implementation, simulation and experimental study of Lyapunov-based two-degree-of-freedom model reference adaptive controller of axial-piston pump.

The main contributions of this article are as follows:

For the first time a Lyapunov-based two-degree-of-freedom (2DoF) model reference adaptive controller (MRAC) for real-time displacement volume regulation of an axial-piston pump is proposed.

The stability of the designed closed loop system is theoretically proven. The tracking error convergence to zero is guaranteed in the case of bounded reference signal.

Demonstrates experimentally closed-loop stability through the observation of tracking error convergence to zero in the presence of load-dependent variability in the pump’s static gain.

Provides a computationally efficient discretized controller implementation suitable for real-time industrial PLC operation. This controller is implemented and validated by a real-world experiment.

The controller’s performance is compared to classical PI, gradient based MRAC, and gain-scheduling adaptive controllers via experimental results on a laboratory hydraulic test bench.

This article is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the laboratory test setup description. In

Section 3, the

Lyapunov-based model reference adaptive controller design is shown,

Section 4 presents the experimental evaluation of the designed controller, and

Section 5 details the conclusions.

3. Lyapunov-Based Model Reference Adaptive Controller Design

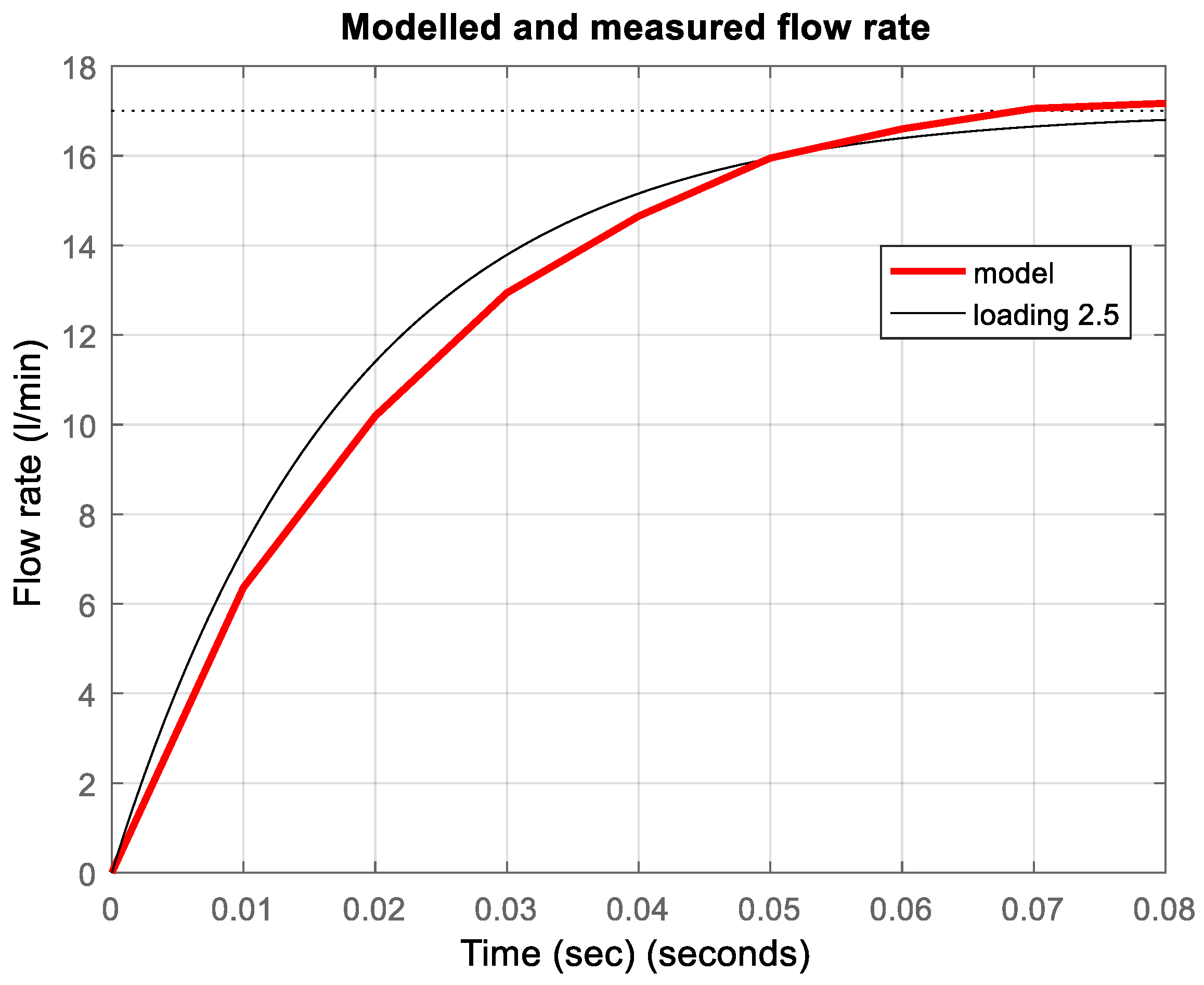

Our main purpose is to design a simple controller that can control the flow rate of axial-piston pump in a wide range of working conditions and to provide control quality and stability of a closed loop system. Moreover, this controller must be sufficiently simple in order to permit easy, real-time implementation in conventional control devices. It is well known that such a controller is the model reference adaptive controller (MRAC) designed on the basis of the Lyapunov stability criteria. The MRAC provides a control performance in case of unknown exactly plant parameters. The controller design requires sufficiently simple plant model. Thus, to estimate such a model, an experiment using a step input signal with an amplitude of 100 mV is performed. The responses are presented in

Figure 3. They are measured for loadings of 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 4, and 5 (these loadings are realized by setting a manually controlled adjustable precision throttle valve at positions of 1.5 mm, 2 mm, 2.5 mm, 3 mm, 4 mm, and 5 mm). It is seen that the plant static gain

depends on current loading. The steady state value of flow rate for loading 5 is approximately 21.5 L/min, since one for loading 1.5 is approximately 12 L/min. Thus, the static gain of the pump

takes values in range

(the amplitude of input signal is 100 mV). As can be seen in

Figure 3, the settling time of the axial-piston pump in respect to the flow rate varies between 0.06 s and 0.09 s for a complete working range. Also, it is obvious that the axial-piston dynamics can be approximated sufficiently well by a first order differential equation

where

is the measured axial-piston pump flow rate and

is the control action.

Due to the approximately constant value of settling time for all loadings, the rough approximation of plant dynamics can be achieved with time constant

s, but it should be noted that its exact value is unknown. For example, the static gain for loading 2.5 is

. The measured step response of model (1) for loading 2.5 is presented in

Figure 4.

As can be seen from

Figure 4, the model (1) approximates plant dynamics for loading of 2.5. In order to compensate for unknown values of plant static gain and plant time constant for various loading conditions the two-degree-of-freedom MRAC is designed. Its feedback and feedforward dynamics are given by

where

is desired flow rate (reference signal),

and

are controller parameters. The closed loop system dynamics is described by

The MRAC design goal is to determine the controller parameters in such a manner that output signal

converges to output signal of reference model

where

is the reference model output and

s is the reference model time constant. The reference model static gain is chosen to take the value of 1, because the pump flow rate should be equal to the desired flow rate in steady state mode. The value of

is smaller than one of

in order to obtain smaller settling time of closed loop system. From Equations (3) and (4) it is seen that if

then the closed loop dynamics will be the same as one for reference model (4). The problem is that the exact values of plant model parameters

and

are unknown. Thus, instead of “ideal” controller parameters

and

in control signal (2), their time varying estimates

and

are used. The difference between the dynamics of the reference model and closed loop system is described by equation

where

is the model reference error. After substituting the measured output and reference model output from Equations (3) and (4) into Equation (6), one obtains

After elementary conversions one obtain

Taking into account expression (5), Equation (9) can be rewritten as follows

where

are errors of controller parameters.

Lemma 1. Let are unknown plant gain and time constant and; is known reference model time constant and are constants andThen the model reference error is bounded. Moreover, if the reference signal is bounded then Proof. The possible candidate for

Lyapunov function for system (9) is

where

are constants.

It is clearly that

is positive definite, i.e.,

It is known that the

is a Lyapunov function if its total derivative respect to time satisfies condition

The time derivative of (13) is

After substituting (9) in (16) one obtains

By regrouping (17) one obtains

After substitution of (11) into (18) the time derivative of (13) is

Clearly

and

are bounded (

). If the reference signal

is bounded, then the

from Equation (4) is bounded. Therefore output

is bounded too (due to

). Thus, as can be seen from Equation (9) the

is also bounded. The second time derivative of the

Lyapunov function (13) is

that is bounded too and

is uniformly continuous. Therefore, according to

Barbalat’s lemma, the condition (12) holds. □

Corollary 1. Taking into account expressions (11) and (12) it is concluded that Expression (21) does not guarantee that the controller parameters converge to ‘’ideal’’ values (5). Indeed, the tracking error

converge to zero and it is the output of a stable system (1), so the input signal of this system

should converge to zero. Also

and

converge to constant values

and

that should satisfy

It should be noted that if the reference signal is constant

for

then

for

and the following is hold

Equation (23) only implies

which gives an infinite number of solutions over a straight line and does not guarantee that

and

. The expression (22) can be written as

It is well known [

41] that if for any

, there are

such that

then

is persistently exciting that guarantee

. It can be shown that the designed control system condition (25) is satisfied if the reference signal contains at least one sinusoid. It should be noted that in a hydraulic control system, the most commonly used reference signals are constant or piecewise constant that led to violation of (25) and

, and

. Nevertheless, the control system has excellent tracking performance (the control system output signal tracks the reference model output). In more rare cases in hydraulic control, the reference signal is periodic rectangular pulses, then the controller parameters converge to their “ideal” values.

Constants

and

in expressions (11) are algorithm tunable parameters. Larger values of

and

lead to fast adaptation process but to large oscillations in the adaptation transient response. Moreover, in real-world implementation, the values

and

are limited by measurement noise and actuator amplitude limitations. However, for real-time implementation of the model reference adaptive control algorithm, derivatives in Equation (13) are approximated by first backward difference

with

s is sample time. It should be noted that Equation (26) represented discrete time realization of continuous control law. After discretization of (4) and taking into account dynamics of zero order holder the discrete time reference model is described by

where

is time shift operator. Applying operator

to Equation (26) one obtains

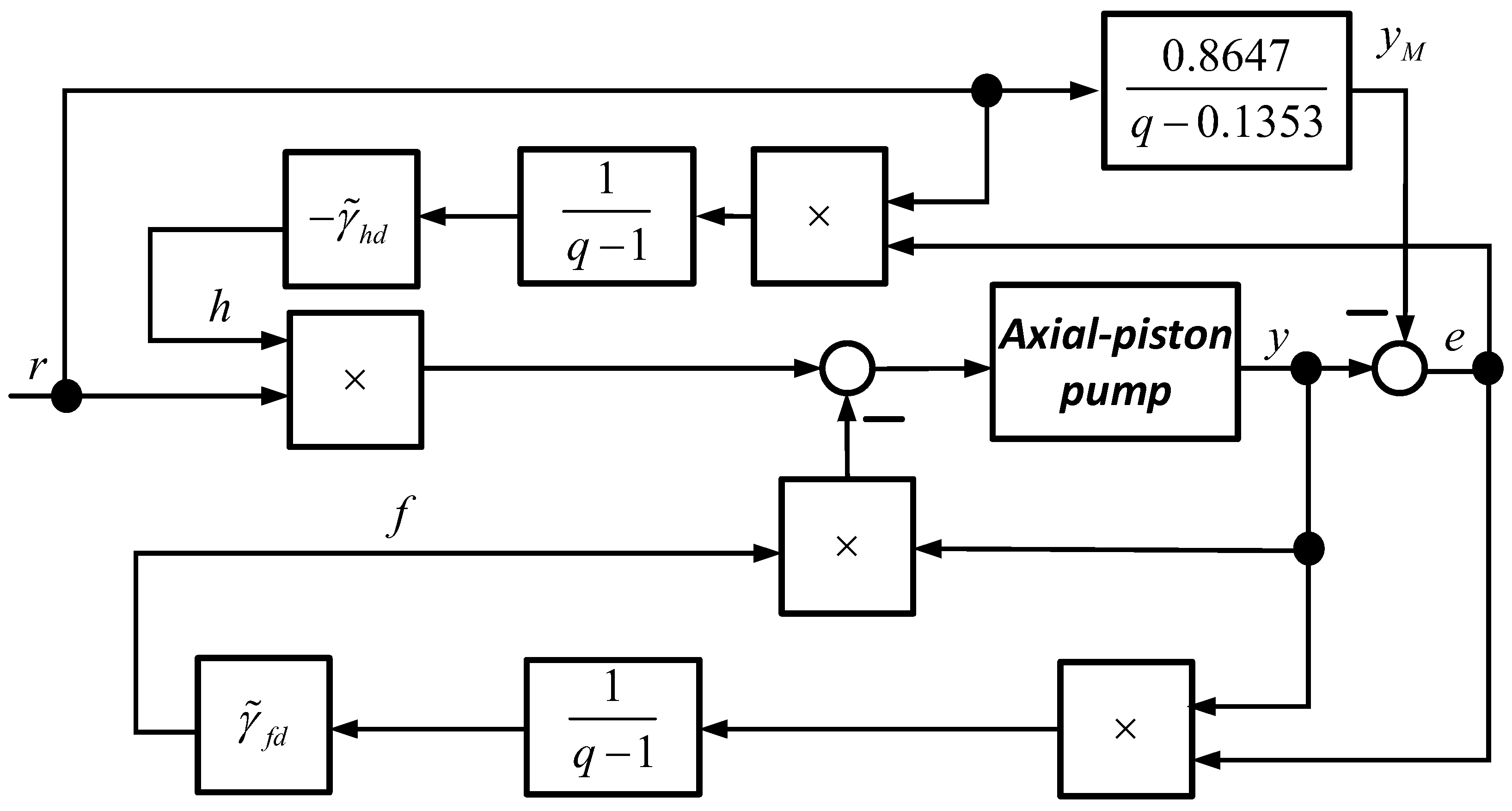

Finally, the block diagram of the adaptive closed loop system is presented in

Figure 5.

The values are experimentally determined. They provide a good compromise between oscillations in control signal and adaptation time.

In order to investigate the quality of the designed controller and to investigate the possibilities of an adaptive control approach for real-time control of the axial-piston pump, a comparison with the previously designed model reference adaptive controller (MRAC) [

42] and gain scheduling adaptive controller (GSAC) [

43] is performed.

The previously designed MRAC uses the reference model (27) and forms the control signal according to Equation (29). The controller parameters

and

are evaluated by the expressions [

42]

The GSAC uses the linear parameter-varying model of the axial-piston pump [

43]

where

The control signal is evaluated by equations

where

is the reference error,

is an anti-wind-up gain that is chosen experimentally to achieve proper wind-up compensation and

is either the control signal upper bound or control signal lower bound:

The controller parameters are evaluated as follows:

4. Experimental Evaluation of Lyapunov-Based MRAC

4.1. Testbench Controller Implementation

The testbench architecture for controller implementation represents a distributed real-time control system where the designed controller, built and tested in Simulink, operates in direct coordination with a Danfoss industrial PLC [

44] via a Controller Area Network (CAN) bus. In this configuration, the Simulink environment functions not merely as a simulation platform, but as a real-time controller executing compiled code that interacts continuously with the physical PLC hardware. The CAN bus provides a deterministic communication backbone that allows the timely exchange of control commands, sensor feedback, and synchronization signals between the two systems.

To ensure that both the PLC and the Simulink-based controller remain in synchronization during execution, the PLC periodically transmits a synchronization packet in blocking communication mode over the CAN. This signal effectively blocks the execution of the Simulink model until the synchronization packet arrives. Then, the model logic is executed as fast as the host CPU allows to generate a response packet to the PLC in the same sampling time. In this way, the system imposes a hardware-driven timing constraint that guarantees deterministic sampling and response intervals. In practice, this means the Simulink algorithm only proceeds to its next computation step when the synchronization signal from the PLC arrives, achieving precise cooperative timing similar to a real-time scheduling system. Of course, such architecture has limited application to laboratory setups for rapid prototyping due to the general purpose operating system at the host.

The Simulink model hosts the adaptive controller and runs with a fixed sampling rate of 100 Hz, which provides a sufficiently high resolution for precise pump flow regulation. This sampling frequency matches flow rate sensor capabilities and ensures that even fast variations in hydraulic flow can be corrected by the control algorithm. In operation, the control outputs computed by the Simulink algorithm are transmitted to the VT-5041 amplifier’s power stage, which in turn actuates the proportional valve solenoid.

4.2. Experimental Results

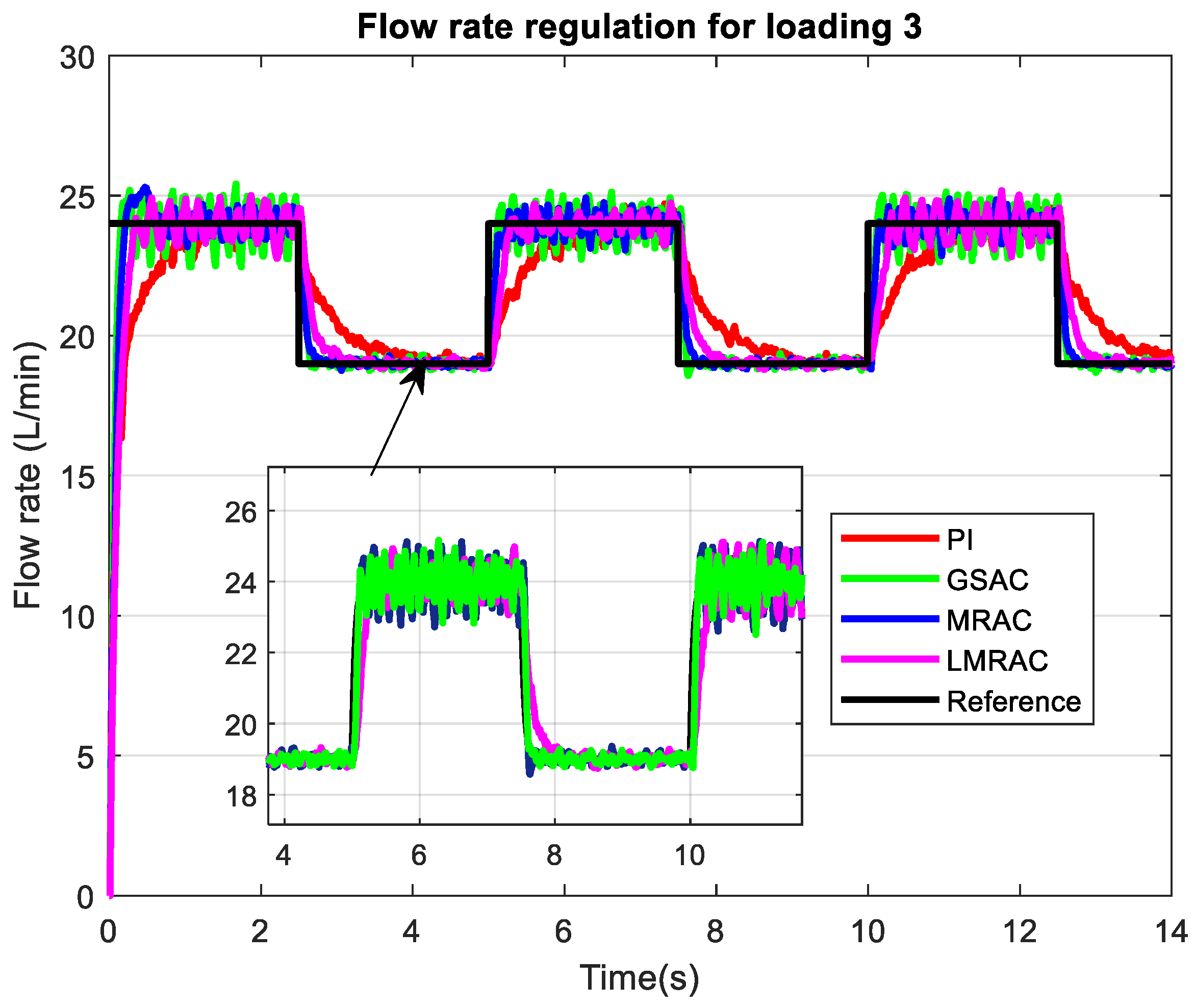

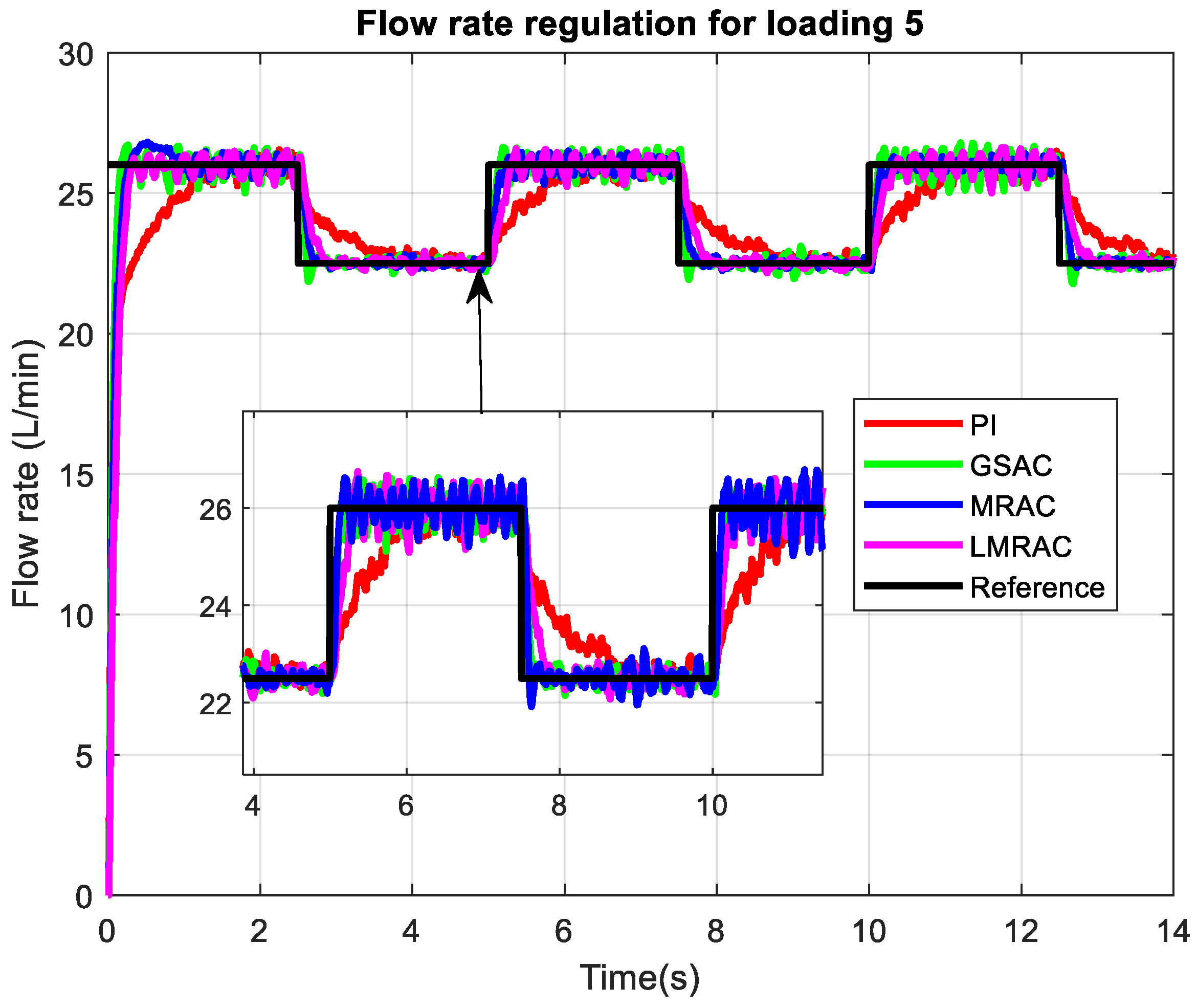

The performance of adaptive controllers is examined for a wide range of loading conditions and compared with a previously designed MRAC, GSAC, and conventional PI controller. Flow rate regulation in four control systems using a

Lyapunov-based model reference adaptive control system (LMRAC), model reference adaptive control system (MRAC), gain scheduling adaptive control system (GSAC), and control system with conventional PI controller (PI) was tested for highest loading imposed on the pump output, which is presented in

Figure 6. The desired flow rate in this mode is between 14 and 17 L/min.

The controllers show marked differences in their dynamic and steady-state behaviors. The initial rise times for all controllers are rapid. The LMRAC and PI controllers closely mirror each other, showing no overshoot, moderate settling times above 0.5 s, and relatively low noise sensitivity. The GSAC and MRAC exhibit slightly faster rise times compared to LMRAC, with GSAC tending to be more aggressive, resulting in minor overshoots.

Similarly,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 demonstrate controller behavior for lower loading conditions corresponding to different levels of shunt valve opening in millimeters. For loading 3, where pump output is less restricted and the throttle valve is more open than loading 2, the difference between adaptive controllers (LMRAC, MRAC, GSAC) becomes less pronounced in terms of settling time. Since the resistance of the pump output is reduced, the adaptive controllers achieve reference value in less than 0.25 s, which is exceptionally fast for pump output regulation. The GSAC experienced more oscillations at a higher flow rate reference with an amplitude up to 0.5 L/min, while the MRAC and LMRAC have similar lower steady state errors. However, it should be noted that an initial overshoot for the MRAC during the starting of the system is observed. while such overshoot is absent for the LMRAC. As a conventional PI controller is not tuned for this particular loading, it experienced a considerable increase in settling time, though with a more damped response with respect to noise, which is expected due to the shift in the open loop frequency response to lower frequencies.

For loading 4 (corresponding to less restriction to output flow compared to loading 3) we observed more damping behavior of the adaptive controllers with respect to the steady state oscillations. Here, LMRAC demonstrated a little bit higher steady state deviations than MRAC during the startup step, which became reduced in the following reference changes. However, the MRAC, again, had an obvious overshoot up to 0.3 L/min during the startup step, which became corrected with time as well. The conventional PI controller continued to underperform compared to adaptive controllers, due to its more conservative tuning required to handle variable load conditions.

Lowest loading 5 corresponds to minimal restriction to pump output with the same range for flow rate commands as we had for loading 4. The behavior of the adaptive controllers was again similar with a very fast rise time and settling time. The steady state noise oscillations at high flow rates were similar between all controllers, with the GSAC showing increased oscillation amplitude during the third reference step. That points to its limited robustness. The MRAC continued to experience a startup overshot of about 0.3–0.5 L/min which was corrected with following operation of the controller. The PI controller demonstrated a faster response compared to higher loading conditions but was still far behind the adaptive counterparts.

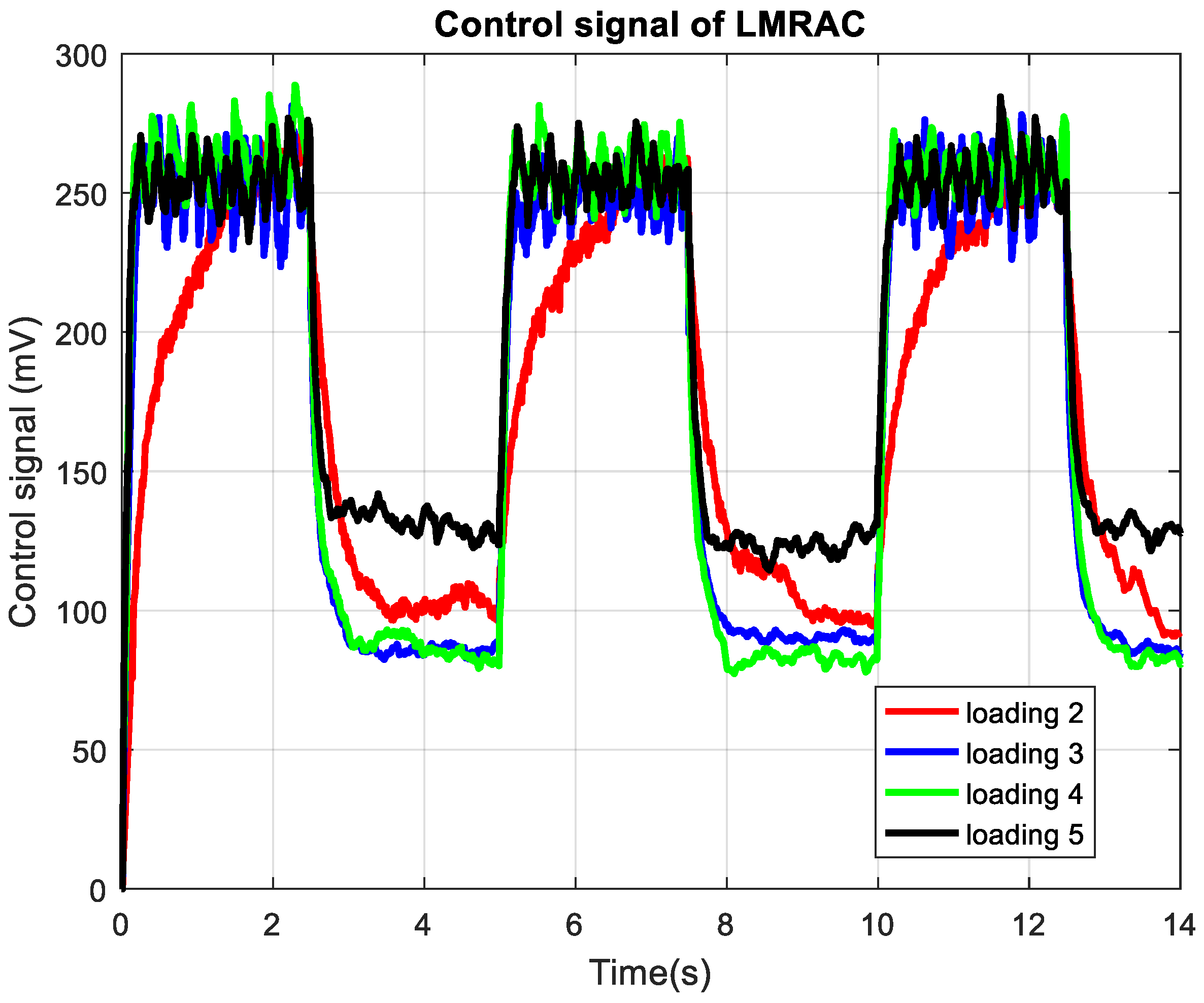

The calculated control signals for a

Lyapunov-based model reference adaptive control system under different loading conditions are visualized in

Figure 10 and control signals for the PI controller for the same loading conditions are in

Figure 11. As the load increased for LMRAC, the control signal amplitude first rises accordingly, indicating the controller’s adaptive compensation for the varying plant gain. However, when reaching the highest loading, the control amplitude became reduced again, notably to compensate for the reduced stability margin of the pump output and susceptibility to oscillatory behavior. Across all loadings from 3 to 5, the controller exhibited rapid transitions in response to the step changes in reference.

Notable differences emerge in the control action for the PI controller compared to the adaptive controllers. The PI controller exhibited consistent low frequency behavior with reduced, but not absent, noise sensitivity. The signal shape demonstrates the inherent limitations of fixed-gain regulation. By keeping the same waveform structure, yet not able to fully compensate for changing plant gain, the result is a bigger output error and less differentiated response among loading curves.

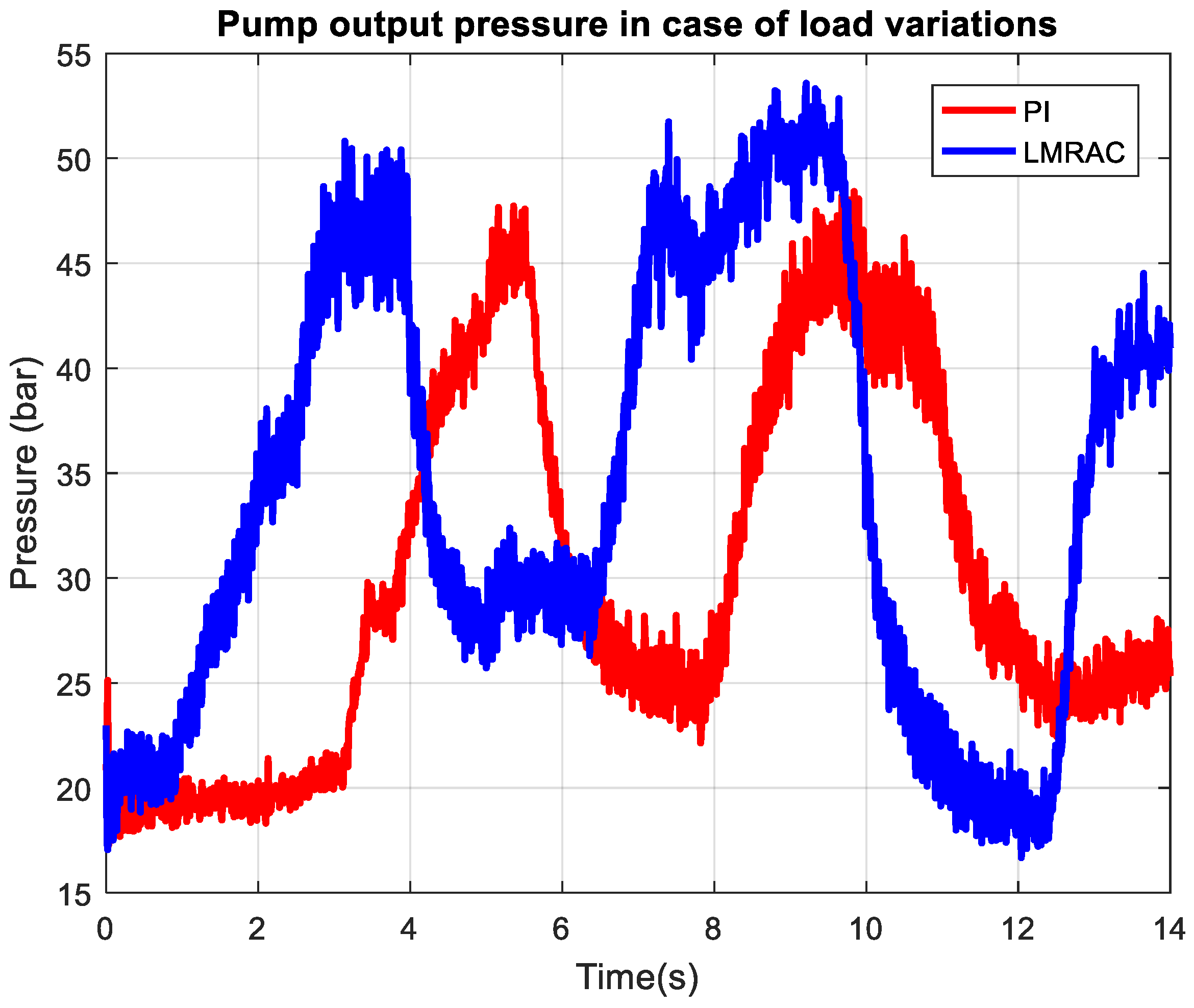

The extension of loading on the system can be appreciated by looking at pump output pressures presented in

Figure 12 for LMRAC and in

Figure 13 for the conventional PI controller. The pressure increases exponentially with loading from 20 bars to above 100 bars, intermittently reaching 120 bars, which is limited by the pressure-relief valve acting in this range. The output pressure decreases progressively from loading 2 to loading 5, since less restriction yields lower pressure for the same flow setpoint. The controller tracks the reference-induced step changes with transitions between high- and low-pressure states, maintaining the pressure level appropriate to each loading curve. Pressure overshoot and steady-state oscillations are more visible at the highest pressure, reflecting the challenge of controlling more restricted flow and greater pump effort.

In order to numerically compare the control system performance, the following index is introduced

It should be noted that the axial-piston pump flow rate takes values between 10 L/min and 26 L/min, whereas the control signal takes values in range 0–1000 mV. So, the first term in (35) will take values in range

, while the second term will take values up to

. By weighting coefficient

the values of the second term are scaled to the values of the first term and the control signal has approximately the same weight as one of pump flow.

Table 1 presents values of index (35) for the four control systems under various loading conditions. The index (35) is evaluated for

s and

s according to the results in

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9. The results clearly demonstrate that the

Lyapunov MRAC consistently achieves lower index (35) values across all tested loadings (2, 3, 4, and 5), indicating superior tracking accuracy and transient performance compared to the PI controller. Specifically, the index (35) for LMRAC ranges from 4.0497 to 4.5942, while the PI controller’s index (35) is significantly higher, ranging from 4.3930 to 6.0027, with the largest performance gap observed at loading 4. This highlights the advantage of the

Lyapunov-based MRAC in adapting to varying system dynamics and maintaining robust control quality, especially as the system load changes, whereas the PI controller’s fixed parameters result in degraded performance under such variations. It is seen that the three adaptive control systems have similar performance. For loading 2, the smallest value of index (35) value is for LMRAC, since for loading 5 the lowest value is for GSAC, but for the whole working range the values are very close. The advantage of LMRAC is that the stability of the system is theoretically guaranteed. From a numerical point of view, all three adaptive systems are sufficiently simple for real-time implementation with a conventional microcontroller.

In order to investigate the developed

Lyapunov-based adaptive controller in different working modes, experiments with dynamically changing load conditions were performed. The realization of the dynamic load pressure disturbance is performed by manual adjustment of precise throttle valve. This is performed in both directions (open/close) for random time moments with various adjustment velocities.

Figure 14 shows the measured flow rate of the axial-piston pump for LMRAC and PI control systems in case of significant variations in hydraulic loading, with multiple reference signal changes appearing throughout the experiment. Despite these dynamic disturbances, the flow rate remains tightly regulated and follows the reference trajectory with a settling time that is smaller than 250 ms without undershoot and overshoot. The PI controller reacts slower than the adaptive controller.

The axial-piston pump output pressure in case of dynamically changing load is presented in

Figure 15. This result reveals real-time insight into how the control system changes with various types of load fluctuations. During the experiment, the pump output pressure exhibits marked transient peaks and grooves that correspond to each load disturbance.

Figure 16 depicts the control action of the LMRAC in response to dynamically varying load conditions. As can be seen, the control signal changes rapidly in order to compensate for each pump load. In this way, the system maintains the desired flow rate level. The control signal for the adaptive controller is smoother than one for the conventional PI controller, which is more appropriate for the operational mode of the electro-hydraulic proportional spool valve.

5. Conclusions

The developed Lyapunov-based two-degree-of-freedom model reference adaptive controller (LMRAC) demonstrates significant theoretical and practical advancements in axial-piston pump control. By employing Lyapunov’s direct stability method, the controller architecture integrates a first-order reference model and adaptively adjusts feedforward and feedback gains through discrete-time update laws derived from stability criteria. The adaptation mechanism ensures asymptotic tracking while compensating for load-dependent variations in the pump’s static gain. This theoretical framework guarantees closed-loop stability by constructing a Lyapunov function whose time derivative remains negative definite, forcing the tracking error to converge to zero. The discretized implementation maintains computational efficiency for real-time operation on industrial PLCs, balancing rapid parameter convergence with noise resilience through carefully tuned adaptation rates.

Experimental validation across loading conditions confirmed the controller’s superiority over conventional PI control, with integral square error (ISE) reductions. The LMRAC’s adaptive gains enabled faster settling time and improved disturbance rejection under variable pressure loads (20–120 bar), as evidenced by control signals and reduced output oscillations. While both controllers operated within comparable control voltage ranges (70–260 mV), the LMRAC’s nonlinear adaptation laws provided inherent robustness against pump nonlinearities and load sensitivity. These results align with the theoretical predictions from the Lyapunov stability analysis, validating the design methodology’s effectiveness in addressing the challenges of displacement volume regulation in variable-displacement pumps.

The results obtained from experimental validation of the designed LMRAC and previously designed MRAC and GSAC show that the closed loop system with LMRAC achieves similar control performance as ones for other adaptive control systems. However, the main advantage of LMRAC is that the stability is investigated theoretically.

Future work could explore formal robustness analysis against unmodeled dynamics and integration with predictive load estimation techniques.