Abstract

To address the increasing demand for computational and communication resources, modern networked systems often rely on heterogeneous servers, including those requiring setup times, such as virtual machines or servers, and others that are always active. In this paper, we model and analyze the performance of such hybrid systems using a level-dependent quasi-birth-and-death (LDQBD) process. Building upon an existing queueing model, we extend the analysis by considering scalable approximation methods. Since matrix analytic methods become computationally expensive in large-scale settings, we propose a stochastic bounding approach that derives upper and lower bounds for the stationary distribution, thereby significantly reducing computational cost. This approach further provides bounds on the performance metrics of the hybrid system.

Keywords:

stochastic bounds; level-dependent QBD process; hybrid systems; setup times; performance evaluation MSC:

60J22; 60J28; 60K25

1. Introduction

In recent years, communication traffic has been steadily increasing, driven by factors such as the widespread use of Internet-connected devices, including smartphones and tablets, and the growing volume of data generated by digital transformation (DX). To meet this rising demand, 5G networks have been widely deployed. While 5G networks offer high capacity, high speed, low latency, and massive connectivity, they also raise concerns about increased power consumption. As a result, developing operational strategies to mitigate energy-related costs has become a crucial research challenge.

In mobile networks, many network functions are now virtualized, resulting in configurations that combine legacy network equipment with virtualized network functions, resembling a non-standalone 5G architecture. Legacy equipment remains continuously powered on, whereas virtual network functions (VNFs) can be dynamically activated or deactivated. In order to design such a hybrid system that minimizes power consumption, it is important to conduct performance analysis based on mathematical modeling.

A study closely related to the present work is that of Sato et al. [1], who modeled a hybrid system consisting of both servers running on legacy network equipment (hereafter referred to as legacy servers) and virtualized servers (hereafter referred to as virtual servers) that require setup time to become active. Their model extends the frameworks proposed by Phung-Duc et al. [2] and Ren et al. [3] to allow for different processing rates between legacy and virtual servers. Importantly, their model assumes that once a job is assigned to a virtual server, it cannot be transferred back to a legacy server. For details of the job assignment policy, see Sato et al. [1]. They formulated the system as a level-dependent quasi-birth-and-death (LDQBD) process and analyzed its stationary behavior.

In contrast to the models in Phung-Duc et al. [2] and Ren et al. [3], where the special transition structure of the LDQBD process allows efficient computation of stationary performance metrics using the technique of Phung-Duc and Kawanishi [4], the model in Sato et al. [1] lacks such a structure. Consequently, their stationary analysis relies on standard matrix analytic methods.

For the matrix analytic methods, see, for example, Neuts [5] and Latouche and Ramaswami [6]. See also Artalejo and Gómez-Corral [7] for a recent study on queueing systems with complex dynamics. Algorithms for computing the stationary distribution of LDQBD processes were proposed by Bright and Taylor [8], Phung-Duc et al. [9], Baumann and Sandmann [10]. For more general Markov processes, including LDQBD processes, a sequential update algorithm was developed by Masuyama [11]. Since matrix analytic methods require matrix operations, they might become computationally intensive and thus impractical for large-scale systems, as the computational cost grows significantly with the system size (e.g., the number of virtual servers) due to the large matrix dimensions involved.

To address this issue, we focus on bounds for the stationary distribution and its expectations. There is a substantial body of literature analyzing bounds on stationary expectations for Markov processes, including LDQBD processes. Bounding the stationary distribution and performance metrics with the help of a Lyapunov function [12,13] is a common technique in the literature on stochastic models and their applications. For example, systems of stochastic chemical kinetics have been analyzed using LDQBD processes [14], where the Lyapunov function-based approach was applied to bound their stationary distribution. By leveraging information about the moments of the state variables of a Markov process, together with the Lyapunov function-based approach, a tight bounding technique was proposed in [15].

Another approach to obtaining bounds for the stationary distribution is to utilize stochastic comparison methods (see, e.g., [16,17]). The key idea of this approach is to design a new Markov process whose stationary distribution serves as an upper or lower bound, in a certain stochastic ordering, for the stationary distribution of the original Markov process. For an algorithmic approach to such stochastic bounds, see [18]. Furthermore, structural properties of Markov processes, such as lumpability [19] and censoring [20], have also been exploited in bounding techniques [21,22].

In this paper, we analyze the same system model as in Sato et al. [1], which involves both servers with and without setup times formulated as an LDQBD process. Since matrix analytic methods become computationally expensive in large-scale settings, we apply the bounding technique developed by Bright and Taylor [8] to this model. By exploiting the transition structure of the model, we derive upper and lower stochastic bounds for the stationary distribution, which can be computed via recurrence relations without resorting to matrix-based operations. This approach leads to a significant reduction in computational cost. Our contributions are threefold.

- We refine the upper bounding model developed by Bright and Taylor [8], making it tighter across a wider range of system parameters.

- We derive recurrence relations for the stationary distribution that avoid matrix-analytic computations, thereby improving computational efficiency. This development relies on specific structural properties of the transition rates, as in Sato et al. [1].

- We extend the analysis of Kawanishi [23] and further develop a stochastic lower bounding model within the same framework.

We further show that key performance metrics, such as the expected sojourn time computed from the true stationary distribution, are bounded above and below by our proposed stochastic bounds. In addition, we conduct numerical experiments to evaluate the sensitivity of these performance metrics to variations in system parameters.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the system model. Section 3 provides a brief overview of partial order relations and stochastic dominance. Section 4 and Section 5 introduce the proposed upper and lower bounding models, respectively. Section 6 discusses performance bounds based on the proposed upper and lower bounding models. Section 7 presents numerical examples to validate the proposed approach. Finally, Section 8 concludes this paper.

2. System Model

We consider a queueing system with multiple servers, consisting of both legacy servers and virtual servers. Legacy servers are assumed to be always powered on, and incoming jobs are assigned to them preferentially in order to reduce power consumption. When all legacy servers are busy, jobs are assigned to virtual servers. Virtual servers require a setup time before they become available to process jobs. Once a job is assigned to a server, either legacy or virtual, it is completed on that server without migration. After completing a job, a virtual server is immediately turned off if no jobs are waiting in the queue.

Jobs are processed in the order of arrival, i.e., according to the first-come, first-served discipline. If servers are available and no jobs are waiting, an arriving job is processed immediately. Otherwise, the job enters a finite-capacity waiting room. If the buffer is full on arrival, the job is rejected and lost. Each waiting job is associated with a deadline by which its service must begin. If the job’s service is not started before its deadline, it leaves the system without being processed.

Let l and v denote the number of legacy servers and virtual servers, respectively, so that the total number of servers is l + v. The maximum capacity of the entire queueing system, including both servers and waiting space, is denoted by K, and we assume K ≥ l + v. Jobs arrive at the system according to a Poisson process with rate λ. The deadline time associated with each job is assumed to follow an exponential distribution with mean 1 / θ. Service times are exponentially distributed. The mean service time is 1 / μ for legacy servers and 1 / μv for virtual servers. The setup time required before a virtual server becomes active is also assumed to be exponentially distributed, with mean 1 / α. The parameters of the queueing system are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameters of queueing system.

Based on the conditions described above, we model the system as a two-dimensional continuous-time Markov chain , where N(t) denotes the number of active virtual servers that have completed setup at time t, and J(t) represents the total number of jobs being processed by legacy servers and those waiting in the queue at time t. The state space S of the Markov chain is defined as

The continuous-time Markov chain can be regarded as a finite LDQBD process, where J(t) represents the level and N(t) the phase. The transition rate matrix Q of this LDQBD process has the following block-tridiagonal structure:

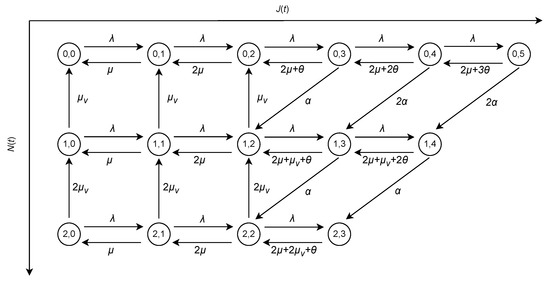

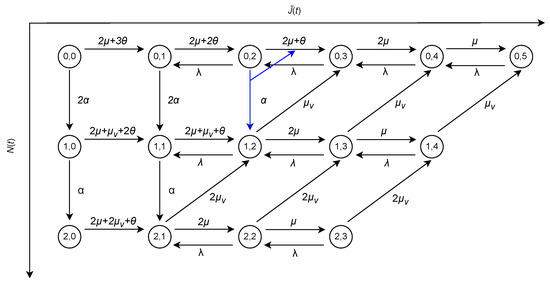

where the block matrices (for 0 ≤ j ≤ K − 1), (for 0 ≤ j ≤ K), and (for 1 ≤ j ≤ K) represent the transitions that increase, preserve, and decrease the level, respectively. The explicit forms of these block matrices are provided in Appendix A. As an illustrative example, Figure 1 shows the state transition diagram for the case where l = 2, v = 2, and K = 5.

Figure 1.

State transition diagram of the model on the state space S.

We can confirm that the generator matrix Q is irreducible. Since the state space is finite, the LDQBD process has a unique stationary distribution π, which satisfies the following system of linear equations

where 0 is the row vector of all zeros, and 1 is the column vector of all ones. Thanks to the block tridiagonal structure of Q, it is well known that π can be computed using the matrix analytic method [6]. Specifically, if we partition the stationary distribution as π = (π0, π1, …, πK), where

and

then the vectors πj can be computed recursively as

where the rate matrix R(j) is defined by

and the auxiliary matrices U(j) are computed via the backward recursion

The vector π0 is obtained as the solution to . The normalization condition leads to

As the size of the block matrices increases, the computational cost grows significantly, especially for large-scale systems. It can be verified that the total number of states of the model is

where Δ = K − v − l ≥ 0. To obtain the stationary distribution of all states, it is necessary to compute R(j) for 1 ≤ j ≤ K. In what follows, we focus on R(j) for 1 ≤ j ≤ K and treat v as an input parameter to analyze the computational complexity with respect to v. Specifically, the size of R(j) for 1 ≤ j ≤ K is

Hence, there are K − v = l + Δ matrices of size (v + 1) × (v + 1), and one matrix of size (k + 1) × k for each 1 ≤ k ≤ v. The total space required to store R(j) for 1 ≤ j ≤ K is therefore

Thus, the space complexity grows as O(v3) with v. Since the most computationally expensive operations for evaluating R(j) are matrix multiplications, it can be verified that the total time required to obtain R(j) for 1 ≤ j ≤ K is

which is of the order O(v4).

To reduce the computational cost of obtaining the stationary distribution, it is effective to adopt the recurrence-based method proposed in Phung-Duc and Kawanishi [4]. However, the transition structure of the model considered in this paper differs from that of the model in Phung-Duc and Kawanishi [4], which prevents direct application of their recurrence-based approach. To address this issue, we construct LDQBD processes that stochastically dominate the original process { X(t) = (N(t), J(t)); t ≥ 0 }, and whose stationary distributions can be computed via recurrence relations.

3. Partial Order Relation and Stochastic Dominance on S

3.1. Partial Order on S

Following the framework of Bright and Taylor [8], we introduce a partial order ⪯ on the state space S defined in Section 2. The quasi order ≺ and the associated partial order ⪯ are defined as follows.

Definition 1

(Quasi order). For two states and , we write if

Definition 2

(Partial order). For , we write if

This ordering will be used in the next subsection to establish stochastic dominance between the original LDQBD process and its bounding processes; see Bright and Taylor [8] for further background.

3.2. Stochastic Dominance on S

We now define stochastic dominance on the partially ordered set S with respect to the partial order relation ⪯ introduced in Section 3.1.

Definition 3

(Stochastic dominance of random variables). Let X and Y be random variables taking values in a partially ordered set S. Let be a real-valued function such that

Then, we say that X is stochastically dominated by Y if

We denote this relation as .

Definition 4

(Stochastic dominance of Markov processes). Let and be continuous-time Markov chains on the state space S equipped with a partial order ⪯. We say that is stochastically dominated by if

Let p = (Pr(X = (i, j)))(i,j)∈S and q = (Pr(Y = (i, j)))(i,j)∈S denote the probability vectors associated with X and Y, respectively. If X ≤ s Y, we write p ≤s q. Therefore, if and have stationary distributions ν and σ, respectively, and stochastically dominates , then we have

4. Upper Bounding Models

In this section, we construct LDQBD processes that stochastically dominate the original model introduced in Section 2. Our approach follows the idea of Bright and Taylor [8], where an LDQBD process providing a stochastic upper bound for a more general (possibly infinite) LDQBD process is constructed.

A key feature of our proposal is that the stationary distribution of the upper bounding process can be computed via recurrence relations. To achieve this, we extend the original state space S, while ensuring that the stationary distribution remains the same as that of the model in Section 2. This extension paves the way for computing the stationary distribution via recurrence relations.

4.1. Extension of State Space

We consider an LDQBD process on the extended state space defined by

Note that , and is infinite. Moreover, we can define the same partial order ⪯ on as on S, by comparing the second components of states.

Let denote the transition rate matrix of the process . We consider to have the following block tridiagonal structure as

where , , and are square matrices of size v + 1, and are defined as follows:

Here, we define a ∧ b ≜ min {a, b} for constants a and b, and [a]+ ≜ max {a, 0}. The diagonal entries of are determined such that the row sums of are zero.

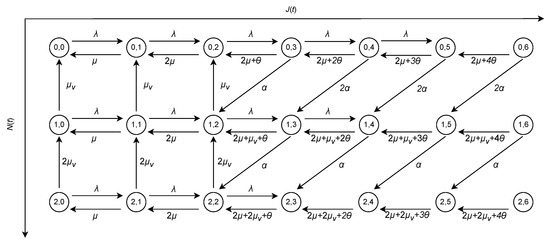

Figure 2 illustrates the state transition diagram of the process on when l = 2, v = 2, and K = 5. The states (2, 4), (1, 5), (2, 5), (0, 6), (1, 6), and (2, 6) are transient states that do not belong to S, and they do not have transitions to states at higher levels. The states (0, j), (1, j), (2, j) for j ≥ 7 are omitted from the figure, as they exhibit the same behavior as (0, 6), (1, 6), (2, 6), respectively.

Figure 2.

State transition diagram of the Markov chain model on the extended state space .

We observe that contains a single irreducible class that exactly coincides with the original state space S. Moreover, the transition rates within this irreducible class are identical to those of the original model on S. This implies that the stationary distribution of , when restricted to this irreducible class, is identical to the stationary distribution π of the original model.

We define the probability vector as

Here, each is defined as

where

Note that for all transient states . Therefore, is essentially the same as the stationary distribution π of the original model on S, padded with zeros corresponding to the transient states in .

4.2. Upper Bounding Model by Bright and Taylor

We briefly summarize the construction of an LDQBD process that stochastically dominates . We begin with the following assumption.

Condition 1.

For all , for every , there exists such that

The following proposition gives a construction of an LDQBD process that stochastically dominates .

Proposition 1

(Theorem 1 in [8]). Suppose the LDQBD process satisfies Condition 1. Define a new LDQBD process with transition rate matrix given by

where the block matrices are defined as

Here, denotes the number of states in level k, i.e., , and , denote the maximum and minimum components of vector a, respectively. Then, the process stochastically dominates .

It should be noted that Condition 1 is satisfied for the specific LDQBD process . Moreover, we observe that has a single finite irreducible class given by

The following corollary is immediate from the stochastic dominance of over .

Corollary 1.

Let denote the stationary distribution on , where

and

If we define the probability vector as

then the following stochastic dominance relation holds.

4.3. Alternative Upper Bounding Model

Using Proposition 1, we can obtain the LDQBD process that stochastically dominates . However, there are several issues that must be addressed.

- The structure of does not preserve the transition structure compatible with the recursive approach developed in Phung-Duc and Kawanishi [4]. As a result, we cannot compute the stationary distribution of using a recurrence relation.

This limitation is a key challenge that we overcome in this paper. In addition, there are the following two issues.

- 2.

- Since the transition rate is defined as the minimum of and , it may result in a conservative upper bounding LDQBD process.

- 3.

- Similarly, since is defined as the maximum of and , it may also lead to a large upper bounding process.

To address the second issue, we suppose that satisfies Condition 1, and we define the normalized transition weights as

Note that by Condition 1.

To resolve the third issue, we define the normalized forward transition weights as

Taking account of the aforementioned issues, we design an alternative LDQBD process that not only stochastically dominates but also enables us to compute its stationary distribution using a recurrence relation. The construction is summarized in the following theorem. The proof is provided in Appendix B.

Theorem 1.

Suppose that satisfies Condition 1. Let us consider the LDQBD process with transition rate matrix given by

where the block matrices are defined as

Here, denotes the Kronecker delta defined by

Then, the process stochastically dominates .

Remark 1.

Note that, for , the term is added to the transition rate in (3). This modification is essential for compensating for the removal of off-diagonal elements in for (see (7)). As a result of this removal, the only possible nonzero transition rates that preserve the level variable appear at levels and , which is the key distinction between and .

We observe that the LDQBD process has a single finite irreducible class given by

All states in are transient. This leads to the following corollary.

Corollary 2.

Let denote the stationary distribution on , where

and

Define the probability vector as

where the zero vectors correspond to the transient states in . Then, the following stochastic dominance relation holds.

Remark 2.

Note that the single irreducible class of the upper bounding model does not include the set of states . Therefore, the transition rates at level do not affect the stationary distribution of . As a result, the transition structure of allows the computation of , which stochastically dominates and is also compatible with the recursive computation method proposed by Phung-Duc and Kawanishi [4].

Example 1.

As an illustrative example, let us consider the case when in Figure 2. In this case, we have

If we apply Proposition 1, then is obtained as follows:

Since the row sums of are greater than or equal to , the condition ensuring that stochastically dominates is satisfied. However, due to the presence of off-diagonal components such as , the resulting transition structure is no longer compatible with the recurrence-based method proposed in Phung-Duc and Kawanishi [4]. In contrast, if we apply Theorem 1, then becomes

Since all the off-diagonal components of are zero, the recurrence-based method can be applied in this case.

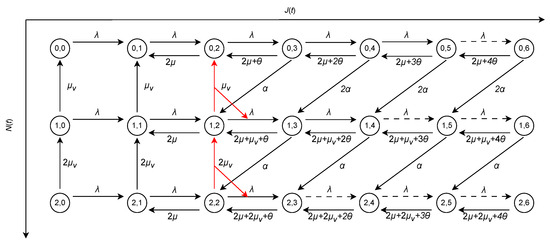

Figure 3 illustrates the state transition diagram of the process on when l = 2, v = 2, and K = 5. It also illustrates the differences in the transition structure before and after applying Theorem 1. The transition rate μv from state (1, 2) to state (0, 2) has been removed and reassigned to the transition rate leading to state (1, 3). Similarly, the transition rate 2μv from state (2, 2) to state (1, 2) has been removed and reassigned to the transition rate leading to state (2, 3). Additionally, transitions represented by dashed arrows with rate λ are newly added.

Figure 3.

State space extension model that gives a stochastic upper bound. Red arrows indicate transitions whose rates have been reassigned: μv from (1, 2) → (0, 2) to (1, 2) → (1, 3), and 2μv from (2, 2) → (1, 2) to (2, 2) → (2, 3). Dashed arrows indicate additional transitions with rate λ.

Since for k ≥ 2 and i ≠ n, the process in Theorem 1 has a transition structure that enables computation of the stationary distribution by recurrence relations, as proposed in Phung-Duc and Kawanishi [4].

4.4. Balance Equations of Stationary Distribution on

We now derive the global balance equations that characterize the stationary distribution on the finite irreducible class of the process .

For i = 0 and 1 < j ≤ K + 1, the global balance equations for are given by

For 1 ≤ i ≤ v and 1 < j ≤ K + 1, the global balance equations for are given by

Note that the above equations do not cover the case where j = 1. To address this, we define a subset of the irreducible class as follows.

From the global balance between and its complement , we obtain

The base case is determined from the normalization condition given by

From the above balance equations and normalization condition, we see that the stationary distribution is uniquely determined.

4.5. Construction of Recurrence Relation

We now construct a recurrence relation for the stationary distribution components on . We begin with the case i = 0. From the global balance Equation (9), we observe that is determined once is given. Next, using (8) for j = K, we find that is determined if is known. Repeating this backward process for j = K − 1, K − 2, …, 2, we see that is recursively determined from . Therefore, starting from the initial value , we obtain the following recurrence relation. The proof is omitted as it is an immediate consequence of the global balance equations.

Lemma 1.

The sequence satisfies the recurrence relation

where the coefficient is given by

and the auxiliary coefficient is recursively defined as

Remark 3.

Lemma 1 implies that all for can be expressed in terms of the initial value . Moreover, from the balance equation between the subset and its complement, we have

Since the right-hand side depends only on for , which are themselves recursively determined by , it follows that is also determined by .

Remark 4.

As in Phung-Duc et al. [2] and Ren et al. [3], the recurrence relations in Lemma 1 can be reformulated without using the auxiliary coefficient as follows.

These recurrence relations involve subtraction, which may lead to numerical instability. In contrast, the formulation given in Lemma 1 avoids subtraction and is numerically more stable.

Next, we consider the recurrence relation for with 1 ≤ i ≤ v. Using the global balance Equations (10) and (11), we obtain a similar recursive structure as follows. The proof is again omitted, as it is an immediate consequence of these equations.

Lemma 2.

For and , satisfies the recurrence relation

where the coefficients are defined as

with the convention that for .

Remark 5.

From Lemma 2, each is expressed in terms of and . Combined with the balance equation

we find that depends on for . Proceeding inductively, and using Lemmas 1 and 2, all components for are recursively determined from the initial value .

Remark 6.

The total number of states in is

which scales as and is asymptotically of the same order as that of the original model. The recurrence-based method computes for all states in using the coefficients , , and . The total space required to store these coefficients is

which grows as . This is asymptotically smaller than the space requirement for storing () in the matrix analytic methods. For each , computing , , and involves at most additions in the denominators of the coefficients. Consequently, the total time required to obtain all coefficients is at most

which grows as . This is also asymptotically smaller than the complexity of computing in the matrix analytic methods.

5. Lower Bounding Model

In constructing the upper bounding LDQBD process, we used J(t) as the level variable, defined as the total number of jobs being processed by legacy servers and those waiting in the queue at time t. A natural idea for deriving a lower bounding LDQBD process is to reverse the direction of the level variable, i.e., to replace J(t) with K − J(t). However, such a straightforward reversal does not yield a LDQBD process that satisfies Condition 1, which is essential for applying the method in [8].

To overcome this issue, we redefine the level variable. Instead of J(t), we consider as the total number of jobs in the system at time t, including those being processed by both legacy and virtual servers as well as those waiting in the queue. Then, we define the level variable by and consider the LDQBD process , where denotes the number of active virtual servers that have completed their setup at time t. The state space of the process is defined by

To derive a lower bounding model for the original process, we construct a LDQBD process with the level variable reversed and appropriately redefined. Let denote the transition rate matrix of on the state space . Then, is constructed so that it has a block tridiagonal structure and is given by

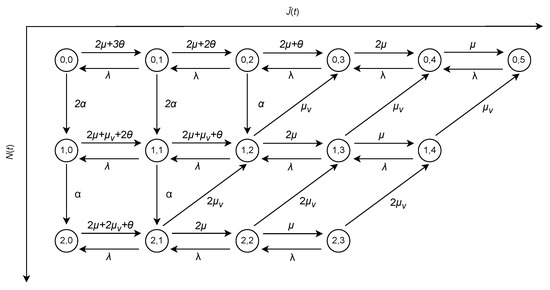

Block matrices of are transition rate matrices, which represent transitions that increase, maintain, and decrease the level variable by one, respectively. The block matrices of are presented explicitly in Appendix A. As an example, we show the state transition diagram for when l = 2, v = 2, and K = 5 in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

State transition diagram of the model on state space .

Remark 7.

In contrast to the upper bounding model, the level variable in the lower bounding model increases due to the departure of jobs rather than their arrival. This reversal reflects the fact that the state with smaller corresponds to a larger number of jobs in the system.

Since is finite, and is irreducible, the stationary distribution of uniquely exists and is given by the solution of the following system of linear equations.

The stationary distribution can be partitioned as , where

and

5.1. Partial Order Relation on

To compare the states based on the number of jobs in the system, we define a partial order on the state space that reflects the reversed level structure.

Definition 5.

For two states , we write if and only if

Definition 6.

For two states and , we write which means that the following condition is satisfied.

Remark 8.

Note that the partial order relation is defined in terms of the level variable , not the actual number of jobs in the system. In our construction, , where j denotes the number of jobs in the system. Therefore, the strict inequality is equivalent to

In other words, holds if and only if the number of jobs in the system in the first state is strictly greater than that in the second.

5.2. Stochastic Dominance on

Let and be random variables taking values in the partially ordered set with the order relation ⪯. We define stochastic dominance in terms of increasing functions on .

Definition 7.

We say that is stochastically dominated by if for every function that is non-decreasing with respect to ⪯, the following holds.

We write if is stochastically dominated by .

5.3. Stochastically Dominating LDQBD for

We construct an LDQBD process that stochastically dominates . Recall that the level variable is defined by , where is the number of jobs in the system at time t. This means that the level increases as the number of jobs decreases. Therefore, when an LDQBD process stochastically dominates with respect to this level variable, it provides a lower bound in terms of the number of jobs in the system.

To construct such a process, we again apply the framework proposed by Bright and Taylor [8], which enables us to construct an LDQBD process that stochastically dominates under a sufficient condition. Unlike the upper bounding model, we do not consider an LDQBD process on an extended state space that includes additional transient states while preserving the same stationary distribution as . However, the following condition plays a crucial role in ensuring the applicability of their method as the upper bounding models.

Condition 2.

For all and , there exists such that

For simplicity, we construct a lower bounding model in the case of K > l + v. We obtain the following theorem for the LDQBD process under Condition 2. The proof is provided in Appendix B.

Theorem 2.

Suppose that and satisfies Condition 2. Define the normalized transition weights

where .

Let be an LDQBD process with transition rate matrix

where the block matrices are defined as

Then, stochastically dominates .

Remark 9.

Due to the transition structure of , we have for all and . Since Condition 2 is satisfied for , we also have for all and .

Remark 10.

The transition rate is set to zero for in order to preserve the transition structure that enables the computation of the stationary distribution of via recurrence relations. To ensure stochastic dominance over , the term is added to the transition rate .

Remark 11.

The process has a single irreducible class given by

All other states in are transient. In particular, all states with level are transient, and hence their stationary probabilities are equal to zero. It should be noted that the assumption of strict inequality is essential to obtain the single irreducible class.

Corollary 3.

Let denote the stationary distribution of the process on the irreducible class , where

and

If we define the probability vector on the entire state space by

then the following stochastic dominance relation holds:

Example 2.

As a concrete example, let us consider the case where and in Figure 4. In these cases, the original block matrices and are given by

Applying Theorem 2, we obtain the modified block matrices and as follows:

Here, ∗ denotes certain positive values that satisfy the conditions specified in Theorem 2.

In Figure 5, we illustrate the transition structure of the process before and after applying Theorem 2. We observe that the transition labeled α from state (0, 2) to state (1, 2) is removed, and its rate is instead added to the transition from state (0, 2) to state (0, 3). As a result, the modified process has a transition structure that allows for efficient computation of the stationary distribution via recurrence relations, as proposed in Phung-Duc and Kawanishi [4].

Figure 5.

Stochastic lower bounding model. Blue arrows indicate the reassignment of the rate from (0, 2) → (1, 2) to (0, 2) → (0, 3).

5.4. Balance Equations of Stationary Distributions in Irreducible Class

We now derive the global balance equations that characterize the stationary distribution over the irreducible class of the process .

For i = v and 1 < j′ ≤ K − v, the global balance equations of are given by

For 0 ≤ i ≤ v − 1 and 1 < j′ ≤ K − i, the global balance equations of are given by

The global balance equations above do not include expressions for with 0 ≤ i ≤ v. To obtain these, we define a subset of the irreducible class as

and consider the total flow between and its complement in . From this, we obtain

Finally, is determined via the normalization condition given by

5.5. Construction of Recurrence Relation

We now construct recurrence relations that determine the stationary probabilities for 1 < j′ ≤ K − v. Observe from the global balance Equation (20) that is determined if is given. Similarly, from (19) at j′ = K − v − 1, since has already been determined from , it follows that is determined from . Proceeding recursively, for any 1 < j′ ≤ K − v, can be determined from . Therefore, the sequence is determined by a recurrence relation starting from . The proof is omitted, as it is analogous to that of Lemma 1.

Lemma 3.

The stationary probability for satisfies the recurrence relation

where the coefficient is given by

and the auxiliary sequence is recursively defined as

Remark 12.

From Lemma 3, we observe that each for can be recursively expressed in terms of . Furthermore, consider the balance equation between the subset and its complement . This equation takes the following form.

Since the right-hand side consists only of terms for , which in turn can be written in terms of , it follows that can also be expressed as a function of .

Using the global balance Equations (21) and (22), we obtain similar recursive relations as follows. The proof is again omitted, as it is standard and analogous to that of Lemma 2.

Lemma 4.

For and , the stationary probability satisfies the following recurrence relation

where

with the convention that for .

Remark 13.

From Lemma 4, it follows that the sequence for can be expressed in terms of and for . In addition, consider the balance equation between and its complement obtained as

The right-hand side depends only on for , and thus can be written in terms of . Furthermore, from Lemma 3, and (for ) are also expressed in terms of . Hence, and all (for ) can be expressed in terms of .

By iterating this argument for , using the balance equations between and , and applying Lemma 4 repeatedly, we conclude that all for and can ultimately be expressed in terms of .

6. Bounds of Performance Metrics

This section presents bounds for key performance metrics. It is important to note that the partial order relations underlying the stochastic comparison are defined with respect to the level variables of the LDQBD processes, but the definitions of the level variables differ between the upper and lower bounding models. In the upper bounding model, the level variable is defined as the sum of the number of jobs being processed by the legacy servers and the number of jobs waiting in the queue. Accordingly, the resulting performance bounds pertain to the number of waiting jobs. In contrast, in the lower bounding model, the level variable represents the total number of jobs in the system, including both jobs in waiting and those in service. Thus, the bounds derived from the lower model are based on the total number of jobs in system.

6.1. Upper Bound of Performance Metrics

Let Lq denote the expected number of jobs waiting in the queue in the original model, whose stationary distribution is denoted by π. Let denote the corresponding expectation in the upper bounding model with stationary distribution . Define a monotone function by

Since and π have the same support and satisfy , we obtain the following inequality:

Note that is the zero vector, and thus the sum over j = 0 to K + 1 does not affect the total value.

Let Wq and PB denote the expected waiting time and the loss probability of a job in the original model with stationary distribution π, respectively. By applying Little’s law, we obtain the following relation:

where is any non-negative constant satisfying . It should be emphasized that although PB can be expressed as

we cannot guarantee the inequality

In our stochastic dominance framework, performance metrics can be compared when they can be represented as expectations of monotone functions. Since the loss rate PB cannot be expressed as a monotone function with respect to the chosen partial order, it cannot be bounded above using the upper bounding distribution , and hence cannot be chosen as . As a result, in order to evaluate an upper bound on Wq, it is necessary to use an external estimate satisfying .

To obtain which is easy to calculate and still holds the relation , we consider the LDQBD process with the level variable as the number of jobs in the system with the stationary distribution . According to [8], the probability distribution that satisfies for any is given by

where

for 1 ≤ j ≤ K. Since by the PASTA (Poisson Arrivals See Time Averages) property [24], we can choose such that by letting . Therefore, Wq is bounded by which is given by

Let W denote the expected sojourn time in the original system, i.e., the expected total time a job spends in the system. Then, we have

where sl is the probability that a job does not abandon the queue and is served by a legacy server, and sv is the probability that a job does not abandon the queue and is served by a virtual server. Since sl ≤ 1 and sv ≤ 1, we obtain the following upper bound:

Therefore, by using the previously obtained bound , we obtain the upper bound Wu for W as

6.2. Lower Bound of Performance Metrics

Let us choose a monotone function f on defined by f((i, j′)) = j′ for . Since , the following inequality holds:

Let L denote the expected number of jobs in the system in the original model with stationary distribution , and let Ll denote that of the lower bounding model with stationary distribution . Since the level variable of the process is related to the actual number of jobs by , we have

Next, let PB and denote the job loss rates in the original and lower bounding models, respectively. Since and the probability masses of are all zero, we have . Therefore,

which gives a lower bound for the expected sojourn time.

7. Numerical Results

In this section, we present numerical results based on the stationary distribution of the LDQBD process. Specifically, we provide two types of validation: (i) a comparison between the numerical results and the upper bounding models given in Proposition 1 and Theorem 1 and (ii) a comparison between the upper and lower bounds established in Theorems 1 and 2.

7.1. Comparison of Upper Bounding Models

Table 2 compares the marginal tail probabilities , , and , obtained from the original model, Proposition 1, and Theorem 1, respectively. We consider two values of the parameter λ, namely λ = 1 and λ = 10, while fixing the remaining parameters at l = 10, v = 20, K = 35, μ = 1, μv = 2, α = 0.01, and θ = 1. We observe that the marginal tail probabilities obtained from Proposition 1 and Theorem 1 are larger than those of the original model, as expected. However, Theorem 1 provides a tighter upper bound than Proposition 1 for the original model under these parameter settings.

Table 2.

Marginal tail probabilities for the original model, Proposition 1, and Theorem 1.

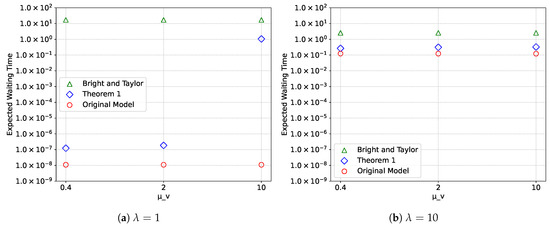

Figure 6 shows a comparison of the expected waiting time obtained from the upper bounding models, as well as from the original model, as the value of μv varies. Figure 6a and Figure 6b correspond to the cases where λ = 1 and λ = 10, respectively. The other parameters are fixed at l = 10, v = 20, K = 35, μ = 1, α = 0.01, and θ = 1.

Figure 6.

Expected waiting time for various values of μv.

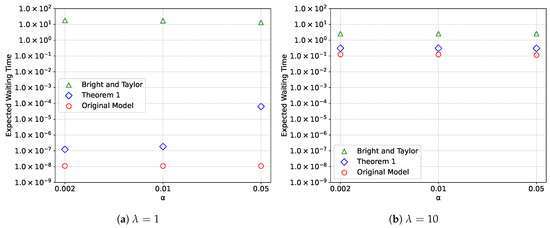

Similarly, Figure 7 shows a comparison of the expected waiting time from the upper bounding models, along with the original model, as the value of α varies. Again, Figure 7a and Figure 7b correspond to λ = 1 and λ = 10, respectively. The remaining parameters are set to l = 10, v = 20, K = 35, μ = 1, μv = 2, and θ = 1.

Figure 7.

Expected waiting time for various values of α.

These figures show that the upper bounding model proposed in Theorem 1 provides a significantly tighter approximation than the one in Proposition 1, originally developed by Bright and Taylor [8], across a wide range of system parameters.

As shown in Example 1, the transition rate matrix given by Proposition 1 is fully populated with nonzero entries related to λ, whereas is not. In contrast, as defined in Theorem 1 preserves zeros in the same positions as . This difference likely accounts for the significant discrepancy between Proposition 1 and Theorem 1 regarding the upper bound of the expected waiting time at λ = 1. It is also worth noting that the expected waiting time based on Theorem 1 can be computed from the stationary distribution obtained via recurrence relations. This implies that one can estimate performance metrics with high accuracy while avoiding expensive computational costs.

7.2. Upper and Lower Bounding Models

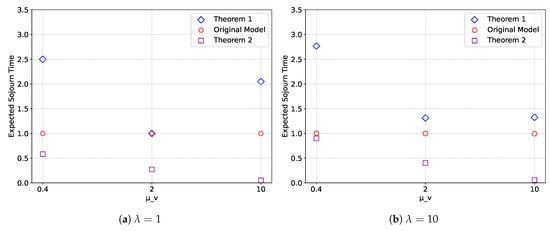

Figure 8 shows a comparison of the expected sojourn time obtained from the upper and lower bounding models, as well as from the original model, for various values of μv. Figure 8a and Figure 8b correspond to the cases where λ = 1 and λ = 10, respectively. The other parameters are fixed at l = 10, v = 20, K = 35, μ = 1, α = 0.01, and θ = 1.

Figure 8.

Expected sojourn time for various values of μv.

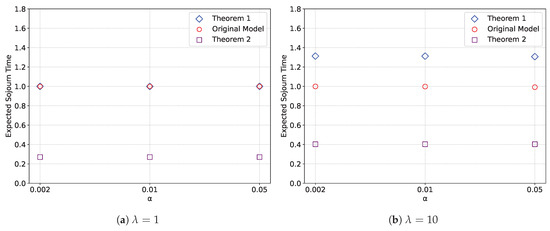

Similarly, Figure 9 presents a comparison of the expected sojourn time obtained from the upper and lower bounding models, along with the original model, for various values of α. Again, Figure 9a and Figure 9b correspond to λ = 1 and λ = 10, respectively. The remaining parameters are set to l = 10, v = 20, K = 35, μ = 1, μv = 2, and θ = 1.

Figure 9.

Expected sojourn time for various values of α.

We observe that the accuracy of the upper bound for the expected sojourn time depends on the value of μv, which may be due to the term in Wu. In contrast, the accuracy of the lower bound deteriorates monotonically as μv increases.

Regarding the dependence on the setup rate α of virtual servers, both the upper and lower bounds for the expected sojourn time appear to be almost insensitive to changes in α, indicating that the range between the bounds is robust with respect to α. Overall, the upper bound provides a more accurate estimate of the expected sojourn time than the lower bound.

7.3. CPU Time

We demonstrate performance improvements achieved by the proposed recurrence-based method. As the performance metric, we use the CPU time required to obtain the upper bound of the expected waiting time. Both the matrix analytic method and our recurrence-based method were implemented in MATLAB® R2025a. Experiments were conducted on a laptop with a 2.4 GHz quad-core CPU and 16 GB of main memory. For each method, CPU times were measured over 10 independent runs.

Table 3 compares the CPU times required to obtain the upper bound of the expected waiting time, based on the stationary distribution in Theorem 1, between the direct application of the matrix analytic method and the proposed recurrence-based method. The parameter v was varied from 1000 to 1500 in increments of 100. The other parameters were fixed at λ = 40, l = 10, μ = 1, α = 0.05, θ = 1, and μv = 2. Note that K = l + v = 10 + v, and thus K also varies with v.

Table 3.

Maximum, average, and minimum CPU times (in seconds) required to obtain the upper bound of the expected waiting time. “N/A” indicates that the computation could not be completed due to insufficient memory.

We observe that the proposed recurrence-based method outperforms the matrix analytic method in terms of CPU time for v = 1000, 1100, and 1200. For v greater than 1200, the matrix analytic method fails to compute the upper bound of the expected waiting time in our computing environment due to insufficient memory. In contrast, the recurrence-based method successfully computes the upper bound in all cases. It is also noteworthy that the CPU time of the recurrence-based method at v = 1500 is almost comparable to that of the matrix analytic method at v = 1200.

8. Conclusions

In this paper, we analyzed the queueing model of hybrid systems proposed by Sato et al. [1], formulated as an LDQBD process. By exploiting the structural properties of the transition rates specific to this model and refining the bounding technique developed by Bright and Taylor [8], we derived both upper and lower stochastic bounds for the stationary distribution, which can be efficiently computed using recurrence relations.

Thanks to these recurrence relations, the upper and lower bounds can be obtained with a significant reduction in computational cost. Furthermore, we showed that key performance metrics computed from the true stationary distribution are bounded above and below by our proposed stochastic bounds. We also conducted numerical experiments to evaluate the sensitivity of these performance metrics to variations in system parameters.

The derivation of the bounds relies heavily on the specific structural properties of the transition rates in the LDQBD process of the queueing model. Extending the applicability of our approach to more general LDQBD processes remains an important topic for future research. Another key challenge is to establish error bounds on the difference between the bounding and the true stationary distributions, which we leave for future work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K.; methodology, K.K.; software, K.K.; validation, K.K. and Y.I.; formal analysis, K.K. and Y.I.; investigation, K.K. and Y.I.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.I.; writing—review and editing, K.K.; visualization, Y.I.; supervision, K.K.; project administration, K.K.; funding acquisition, K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by JSPS KAKENHI 23K10994.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Block Matrices of Q and

This appendix presents the block matrices of Q and explicitly.

Appendix A.1. Block Matrices of Q

The block matrices for 0 ≤ j < l, for 0 ≤ j ≤ l, and for 0 < j ≤ l are (v + 1) × (v + 1) matrices given by

where I is the identity matrix of appropriate size. The exit rate qi,j of state (i, j) ∈ S for 0 ≤ i ≤ v and 0 ≤ j ≤ l is given by

The matrices for l ≤ j < l + v, for l < j ≤ l + v, and for l < j ≤ l + v are (v + 1) × (v + 1) matrices given by

where pi,j = (j − l) ∧ (v − i). The exit rate qi,j of state (i, j) ∈ S, for 0 ≤ i ≤ v and l < j ≤ l + v, is given by

The matrices for l + v ≤ j < K, for l + v < j ≤ K, and for l + v < j ≤ K are (K − j + 1) × (K − j), (K − j + 1) × (K − j + 1), and (K − j + 1) × (K − j + 2) matrices, respectively, and are explicitly given by

where 0⊤ denotes the column vector of all zeros, i.e., the transpose of the row vector 0 defined in the main text. The exit rate qi,j of state (i, j) ∈ S, for 0 ≤ i ≤ K − j and l + v < j ≤ K, is given by

Appendix A.2. Block Matrices of

The block matrices for 0 ≤ j′ < K − l − v, for 0 ≤ j′ < K − l − v, and for 0 < j′ ≤ K − l − v are (v + 1) × (v + 1) matrices given by

where for state with 0 ≤ i ≤ v and 0 ≤ j′ < K − l − v is given by

The matrices for K − l − v ≤ j′ < K − l, for K − l − v ≤ j′ < K − l, and for K − l − v < j′ ≤ K − l are (v + 1) × (v + 1) matrices given by

where if i < K − j′ − l, and otherwise, and . The exit rate of state for 0 ≤ i ≤ v and K − l − v ≤ j′ < K − l is given by

The matrices for K − l ≤ j′ < K, for K − l ≤ j′ ≤ K, and for K − l < j′ ≤ K are (K − j′ + 1) × (K − j′), (K − j′ + 1) × (K − j′ + 1), and (K − j′ + 1) × (K − j′ + 2) matrices, respectively, and are explicitly given by

where the exit rate of state for 0 ≤ i ≤ K − j′ and K − l ≤ j′ ≤ K is given by

Appendix B. Proofs of Theorems 1 and 2

This appendix provides the proofs of Theorems 1 and 2.

Appendix B.1. Preliminaries

Let S be a set equipped with a partial order relation ⪯. A subset Γ ⊂ S is called an increasing set if it satisfies the following condition.

We prove Theorems 1 and 2 using the following lemma, established by Massey [25] for uniform Markov processes and later extended by Brandt and Last [26] to accommodate non-uniform Markov processes.

Lemma A1.

Let and be Markov processes on a common state space S, equipped with a partial order ⪯ . Suppose that for all such that , and for all increasing sets , the following two conditions hold.

- (i)

- If , then

- (ii)

- If , then

Then, stochastically dominates with respect to the partial order ⪯.

Let (M) denote the power set of a set M. Following the idea of [8], we define a family of increasing sets for the LDQBD processes on in the following form.

Note that the family

satisfies the following property:

Similarly, for the LDQBD processes on , we define increasing sets as

and define

which also satisfies the following property.

Appendix B.2. Proof of Theorem 1

For the proof of Theorem 1, we apply Lemma A1 to LDQBD processes defined on the state space , equipped with the partial order ⪯ as defined in Definition 2. We associate q1 in Lemma A1 with the generator of and q2 with that of . We then verify that the two sufficient conditions (i) and (ii) in Lemma A1 are satisfied for every pair of states such that x ⪯ y and for every increasing set of the form ΦI,j defined in the previous subsection.

Before presenting the detailed proof, we outline its structure. The proof is divided into two parts, corresponding to the two sufficient conditions (i) and (ii) in Lemma A1. For each condition, we examine all non-trivial relevant cases for every pair of states satisfying x ⪯ y and for every increasing set of the form ΦI,j.

Proof.

- Verification of condition

We verify condition in Lemma A1.

- In the case of

- –

- For , , we may choose and . Then, it holds thatFrom (5), we haveTherefore,Here, we used the fact that

- –

- For , we may choose and . Then, it holds thatwhere the last equality follows from (4). Thus, the inequality holds.

Therefore, under the condition , condition is satisfied. - In the case of

- –

- For , , we may choose . Then, it holds thatFrom (5), we have .

- –

- For , , we can take . Then, it holds that

- ∗

- If , then by (6), and by (4).

- ∗

- If , then by (7), and by (5).

- -

- For , we may choose . Then, it holds thatwhere the last equality follows from (4).

- –

- For , we can also choose . Then, it holds thatFrom (6), we have .

Therefore, under the condition , condition is satisfied.

- Verification of condition

We verify condition in Lemma A1.

- In the case of

- –

- For , , we may choose and . Then, it holds thatSuppose there exists such that . Since , we haveFrom (2) and (3),which yieldsIf for all , then from (2) and (3),and hence we haveHere, the second equality is justified by .

Therefore, under the condition , condition is satisfied. - In the case of

- –

- For , , we may choose . Then, it holds that

- ∗

- If , then from (2) and (6), we have

- ∗

- If , then from (3) and (7), we haveThe second equality is justified by .

- –

- For , , we can also choose . Then, it holds that

- ∗

- If , then by (1).

- ∗

- If , then by (2).

- ∗

- If , then from (3), we have

- –

- For , we may choose . Then, it holds thatFrom (1) and (6), we have

Therefore, under the condition , condition is satisfied.

Note that we have only considered non-trivial cases. We have thus verified that conditions (i) and (ii) in Lemma A1 hold for all relevant state pairs and increasing sets. Hence, the proof of Theorem 1 is complete. □

Appendix B.3. Proof of Theorem 2

In the following, we verify conditions (i) and (ii) in Lemma A1 by applying to q1 and to q2, respectively. For the proof of Theorem 2, we apply Lemma A1 to LDQBD processes defined on the state space , with the partial order ⪯ given in Definition 6.

Proof.

- Verification of condition

We first verify condition .

- In the case of

- –

- For , , we may take and . Then, it holds thatFrom (16), we have , and hence,Here, we used that .

- –

- For , we may take and . Then, it holds thatwhere the last equality follows from (15).

Thus, condition is satisfied when . - In the case of

- –

- For , , we may take . Then, it holds thatFrom (16), we have , so the condition is satisfied.

- –

- For , , we may also take . Then, it holds that

- ∗

- If , then from (17) and (15), we haveso the inequality is satisfied.

- ∗

- If , then from (18) and (16), we haveso again the inequality holds.

- –

- For , we may take . Then, it holds thatwhere the last equality follows from (15), and thus the inequality is satisfied.

- –

- For , we may also take . Then, it holds thatFrom (17), we have , so the inequality holds.

Therefore, under the condition , condition is satisfied.

- Verification of condition

We next verify condition .

- In the case of

- –

- For , we may choose and . Then, it holds thatSince there exists an such that and , we haveUsing (13) and (14), we obtainand hence we haveTherefore, under the condition , condition is satisfied.

- In the case of

- –

- For , we may choose . Then, it holds that

- ∗

- If , then from (13) and (17), we have

- ∗

- If , then by (18), and using (14),

- ∗

- If , then and . Hence, from (14),

- –

- For , we may choose as well. Then, it holds that

- ∗

- If , then by (12).

- ∗

- If , then by (13).

- ∗

- If , then from (14), we have

- –

- For , we may choose . Then, it holds thatFrom (12) and (17), we haveThus, condition is satisfied when .

In summary, conditions and are satisfied for all non-trivial cases of with , and for every increasing set of the form . Therefore, the proof is complete. □

References

- Sato, M.; Kawamura, K.; Kawanishi, K.; Phung-Duc, T. Modeling and performance analysis of hybrid systems by queues with setup time. Perform. Eval. 2023, 162, 102366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phung-Duc, T.; Ren, Y.; Chen, J.-C.; Yu, Z.-W. Design and analysis of deadline and budget constrained autoscaling (DBCA) algorithm for 5G mobile networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Cloud Computing Technology and Science (CloudCom), Luxembourg, 12–15 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.; Phung-Duc, T.; Chen, J.-C.; Li, F.Y. Enabling dynamic autoscaling for NFV in a non-standalone virtual EPC: Design and analysis. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 7743–7756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phung-Duc, T.; Kawanishi, K. Energy-aware data centers with s-staggered setup and abandonment. In Proceedings of the Analytical and Stochastic Modelling Techniques and Applications (ASMTA 2016), Cardiff, UK, 24–26 August 2016; pp. 269–283. [Google Scholar]

- Neuts, M.F. Matrix-Geometric Solutions in Stochastic Models: An Algorithmic Approach; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Latouche, G.; Ramaswami, V. Introduction to Matrix Analytic Methods in Stochastic Modeling; Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Artalejo, J.R.; Gómez-Corral, A. Retrial Queueing Systems: A Computational Approach; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bright, L.; Taylor, P.G. Calculating the equilibrium distribution in level dependent quasi-birth-and-death processes. Stoch. Model. 1996, 11, 497–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phung-Duc, T.; Masuyama, H.; Kasahara, S.; Takahashi, Y. A simple algorithm for the rate matrices of level-dependent QBD processes. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Queueing Theory and Network Applications (QTNA2010), Beijing, China, 24–26 July 2010; pp. 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, H.; Sandmann, W. Numerical solution of level dependent quasi-birth-and-death processes. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2012, 1, 1561–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuyama, H. A sequential update algorithm for computing the stationary distribution vector in upper block-Hessenberg Markov chains. Queueing Syst. 2019, 92, 173–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweedie, R.L. Sufficient conditions for regularity, recurrence and ergodicity of Markov processes. Math. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 1975, 78, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glynn, P.W.; Zeevi, A. Bounding stationary expectations of Markov processes. Markov Process. Relat. Top. Festschr. Thomas Kurtz 2008, 4, 195–214. [Google Scholar]

- Dayar, T.; Sandmann, W.; Spieler, D.; Wolf, V. Infinite level-dependent QBD processes and matrix-analytic solutions for stochastic chemical kinetics. Adv. Appl. Probab. 2011, 43, 1005–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Somashekar, G.; Delasay, M.; Gandhi, A. Efficient and accurate Lyapunov function-based truncation technique for multi-dimensional Markov chains with applications to discriminatory processor sharing and priority queues. Perform. Eval. 2023, 162, 102356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Stoyan, D. Comparison Methods for Stochastic Models and Risks; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shaked, M.; Shanthikumar, J.G. Stochastic Orders; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fourneau, J.M.; Pekergin, N. An algorithmic approach to stochastic bounds. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Calzarossa, M.C., Tucci, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; Volume 2459, pp. 64–88. [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz, P. Exact and ordinary lumpability in finite Markov chains. J. Appl. Probab. 1994, 31, 3159–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.Q.; Liu, D. The censored Markov chain and the best augmentation. J. Appl. Probab. 1996, 33, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fourneau, J.M.; Lecoz, M.; Quessette, F. Algorithms for an irreducible and lumpable strong stochastic bound. Linear Algebra Its Appl. 2004, 386, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourneau, J.M.; Pekergin, N.; Younès, S. Censoring Markov chains and stochastic bounds. In Proceedings of the Formal Methods and Stochastic Models for Performance Evaluation (EPEW 2007), Berlin, Germany, 27–28 September 2007; pp. 213–227. [Google Scholar]

- Kawanishi, K. Bounding performance of stochastic models for server virtualization in cloud computing. In Proceedings of the 10th International Congress on Industrial and Applied Mathematics (ICIAM 2023), Tokyo, Japan, 20–25 August 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, R.W. Poisson arrivals see time averages. Oper. Res. 1982, 30, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, W.A. Stochastic orderings for Markov processes on partially ordered spaces. Math. Oper. Res. 1987, 12, 350–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, A.; Last, G. On the pathwise comparison of jump processes driven by stochastic intensities. Math. Nachrichten 1994, 167, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).