Abstract

Restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimators are commonly used to obtain unbiased estimators for the variance components in linear mixed models. In modern applications, particularly in genomic studies, the dimension of the design matrix with respect to the random effects can be high. Motivated by this, we first introduce high-dimensional kernel linear mixed models, derive the REML equations, and establish theoretical results on the consistency of REML estimators for several commonly used kernel matrices. The validity of the theories is demonstrated via simulation studies. Our results provide rigorous justification for the consistency of REML estimators in high-dimensional kernel linear mixed models and offer insights into the application of estimating genetic heritability. Finally, we apply the kernel linear mixed models to estimate genetic heritability in a real-world data application.

MSC:

62F12

1. Introduction

Heritability, particularly narrow-sense heritability, refers to the proportion of phenotypic variance explained by additive genetic variance. For example, it is well-known that the estimated heritability of human height is roughly 0.8 [1,2]. However, early identified genes could only explain a small fraction of height heritability. More recently, large-scale genome-wide association studies (GWASs) involving 5.4 million individuals have identified 12,111 height-related single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). It has been shown that common SNPs can explain 40–50% of the phenotypic variation in human height [3]. Therefore, the previously observed “missing heritability” can be attributed to the small effect sizes of individual SNPs. Furthermore, because a classical GWAS relies on linear models and multiple testing procedures, a SNP must meet stringent criteria at the whole-genome level (e.g., p-value < ) to be considered significant. As a result, many SNPs with small yet meaningful effects remain undetectable using classical GWAS methods.

The idea that heritability is spread across multiple SNPs that contribute to phenotypic traits, also known as polygenicity, has been widely accepted over the past few decades. As a result, rather than estimating the individual effect of each SNP, state-of-the-art models in GWASs estimate the cumulative effect of multiple SNPs in a genetic region, such as all SNPs in a gene, a pathway, or even a chromosome. For quantitative traits, linear mixed-effects models are commonly used to model the cumulative effect of multiple SNPs. It was shown that, using a linear mixed model, known as genome-wide complex trait analysis (GCTA) [4], 45% of the variance in human height could be explained by all common SNPs [5]. This finding has since been supported by the large-scale GWAS mentioned above.

Linear mixed-effects models (LMMs) provide powerful alternatives in GWASs, and various studies have explored LMMs in the high-dimensional setting. In Li et al. [6], the authors proposed inference methods for linear mixed models using techniques similar to the debiased LASSO method [7,8], achieving an estimator of the fixed effects with the optimal convergence rate and valid inferential procedures. However, their framework assumes that the cluster size of the random effects is large, which is generally not true in genetic studies where linear mixed-effects models are commonly applied. Similarly, Law and Ritov [9] proposed methods for constructing asymptotic confidence intervals and hypothesis tests for the significance of random effects. In both studies, however, high dimensionality resides in the fixed effects, while the dimension of the random effects is assumed to be low. This limits their applicability to genetic studies, where the SNP matrix is often treated as the design matrix for random effects [4,10].

Therefore, it is of greater interest to investigate the properties of variance component estimators when the random effects are high-dimensional. Jiang et al. [11] provided theoretical guarantees for the consistency of the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimator under the setting where the random-effects design matrix is high-dimensional and random in the so-called linear regime ( for some ). These techniques have since been extended to construct confidence intervals for variance components [12] and to establish the asymptotic normality of heritability estimators based on GWAS summary statistics [13].

Currently, the most commonly used LMMs in GWASs, as studied in Jiang et al. [11], for a polygenetic quantitative trait can be expressed via the following additive model:

where is the fixed effect of the ith individual, which is typically of the form , and are covariates (e.g., age, gender, and race group) of the ith individual; is a set of SNPs; and is the genotype of the jth SNP of the ith individual. is the effect of the jth SNP, which typically follows a normal distribution with being the cardinality of the set . is the random error or other possible environmental effects, which are typically modeled by a normal distribution . By writing , model (1) can be written as

or in a vector form

where , , and . Under the distributional assumptions in Model (1), the distributions of and are

where the matrix is an -matrix containing SNPs in region .

An underlying assumption in Model (1) or (2) is that the genetic effect associated with the quantitative trait of interest is linear. This may not be a reasonable assumption in reality, as generally the relationships between genotypes and phenotypes are rather complex. Therefore, the following semi-parametric models could be more appropriate.

where and is some function space. In particular, let be a reproducing kernel Hilbert space (RKHS) associated with a kernel function . The representer theorem [14] shows that when , the estimating equation for and under penalized least squares is equivalent to the Henderson mixed model equation, which is often used to obtain the BLUP in a linear mixed model. In this case, the linear mixed model is given as

where with being a kernel matrix, , and are independent.

In this paper, we study the consistency of the REML estimator for variance components in a high-dimensional kernel linear mixed-effects model. Such models have also been widely used in spatial statistics [15], as well as in identifying significant genetic variants [10,16] and predicting genetic risk for diseases [17]. The results established in this paper extend the work by Jiang et al. [11] from linear kernels to other commonly used kernels that capture nonlinear genetic effects, thereby providing theoretical justification for the successful application of kernel LMMs in genetic studies.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides the formulation of the REML equations for kernel linear mixed-effects models and the main consistency results for the REML estimators. The main results rely heavily on random matrix theories (RMTs), and a brief review of the RMTs is also given in Section 2. Simulation studies are given in Section 3 to verify the theoretical results, followed by a real-world data application.

Notations : Throughout this paper, bold alphabetic or Greek letters are used for vectors, while bold capital alphabetic or Greek letters are used for matrices. For an matrix , means that is positive and semi-definite, while means that . For a vector , denotes its Euclidean norm, and we use to denote the operator norm of a matrix ; that is, . When is symmetric and positive semi-definite, this is the same as the largest eigenvalue of . is used to denote the determinant of a squared matrix . For two matrices of the same size, denotes the Hadamard product; i.e., . Moreover, if is a univariate function and is a matrix, then denotes a matrix of the same size as and .

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The REML Equations for Variance Components

Let q be the rank of the fixed-effects design matrix and such that and . Then, by multiplying on both sides of Equation (5), we obtain

where and

Let be the probability density function of . Then the restricted log-likelihood of is

where is the ratio between two variance components. With slight abuse of notation, let in what follows.

A well-known result for REML estimators is that they are independent of the choice of , which is based on the following identity [18]

where . Also, let , then

Therefore, , and the restricted log-likelihood function can be written as

By taking the derivatives with respect to and and letting them equal to zero, we know that the REML estimators of and satisfy the following REML equations:

2.2. A Review on Random Matrix Theory

In this section, we briefly review the theory of random matrices. For more details on the application of random matrix theory in statistics, we refer interested readers to Bai and Silverstein [19] and Paul and Aue [20]. Let be an matrix with eigenvalues . The empirical spectral distribution (ESD) of the matrix is defined to be

For a double array of i.i.d. random variables with a mean of 0 and a variance of , write with and . It is well known that the ESD of the sample covariance matrix converges almost surely in distribution to the Marchenko–Pastur (M-P) law.

Theorem 1.

(Marchenko–Pastur Law). Suppose that are i.i.d. random variables with a mean of 0 and a variance of . Also assume that as . Then, with a probability of 1, tends toward the M-P law having density

and has a point mass at the origin if , where .

The following corollary is by Jiang et al. [11], which is a consequence of convergence in distribution and will be frequently used.

Corollary 1.

Under the assumptions of Theorem 1, for the integer l,

In general, the assumptions on i.i.d. can be reduced. The following theorem is Theorem 4.3 in Bai and Silverstein [19].

Theorem 2.

Suppose that the entries of are random variables that are independent of each n and identically distributed for all n and satisfy . Also assume that , is real, and that the empirical distribution function of converges a.s. to a probability distribution function H as . The entries of both and may depend on n. Set

where is symmetric and satisfies almost surely, where H is a distribution (possibly defective) on the real line. Assume that , , and are independent. When as , then the ESD of and converges almost surely as to a nonrandom distribution function F.

The limiting spectral behaviors of have not only been studied, but the limiting spectral behaviors of inner-product kernel matrices have also been studied. Here we quote Theorem 2.1 in El Karoui [21].

Theorem 3.

(Spectrum of Inner-Product Kernel Random Matrices). Let us assume that we observe n i.i.d. random vectors . Consider the kernel matrix with entries

Assume that

- 1.

- ; that is, and remain bounded as .

- 2.

- is a positive definite matrix and remains bounded in p; that is, there exists such that for all p.

- 3.

- has a finite limit; that is, there exists such that .

- 4.

- .

- 5.

- The entries of , a p-dimensional random vector, are i.i.d. Also, as denoted by , the kth entry of , we assume that , , and for some .

- 6.

- f is a function in the neighborhood of and a function in the neighborhood of 0.

Under these assumptions, the kernel matrix can (in probability) be approximated consistently in the operator norm when p and n tend to ∞ by the matrix , where

where

In other words,

El Karoui [21] also studied the behaviors of the spectrum of Euclidean distance kernel random matrices or, in other words, radial basis kernel matrices. The following result is from Theorem 2.2 from El Karoui [21].

Theorem 4.

(Spectrum of Euclidean Distance Kernel Random Matrices). Consider the kernel matrix with entries

Let us call

Let us call ψ the vector with the ith entry . Suppose that the assumptions of Theorem 3 hold, but that conditions 5 and 6 are replaced by

- (5’)

- The entries of , a p-dimensional random vector, are i.i.d. Also, as denoted by the kth entry of , we assume that , , and for some .

- (6’)

- f is in a neighborhood of τ.

Then can be approximated consistently in the operator norm (and in probability) by the matrix , which is defined by

where . In other words,

The following lemma provides a useful bound for the variance of a quadratic form, and its proof is given in Appendix A.

Lemma 1.

Suppose that , with μ being a fixed vector; ; ; and . Then

2.3. Consistency of REML Estimators in Kernel LMMs

In this section, we will show the main results on the consistency of REML estimators for kernel linear mixed models under three commonly used classes of kernel matrices in genetic data analysis. The first one is the weighted product kernel, which is a natural generalization of the product kernel and is the kernel matrix used in a sequence kernel association test (SKAT) [10] in genetic association studies. The other two classes are the inner-product-based kernel matrices and the Euclidean distance-based kernel matrices. An example of an inner-product-based kernel is the polynomial kernel, and an example of a Euclidean distance-based kernel is a Gaussian kernel. Proofs of all results in this section can be found in Appendix A.

2.3.1. Weighted Product Kernel

The following theorem serves as a natural extension of the result by Jiang et al. [11] to the case of a weighted product kernel. It guarantees the consistency of REML estimators of the variance components in kernel linear mixed models when the entries in are i.i.d. and have a finite fourth moment, and the weights in the diagonal matrix are upper and lower bounded.

Theorem 5.

For with entries in and ,

- 1.

- are i.i.d. with , , and ;

- 2.

- withfor some .

Then as and , we have

where is the true value for γ.

In addition, the same result still holds when is replaced by its column standardized version as given in the following corollary. The proofs of the theorem and the following corollary are very similar to the proofs in Jiang et al. [11], and they can be found in Appendix A.

Corollary 2.

Let be a random matrix whose elements are i.i.d. with , , and . Let be the matrix that is obtained by column standardizing the matrix ; i.e.,

where with , , and with . Let be the weight matrix satisfying Equation (11). Then for , as and , we have

where is the true value for γ.

The i.i.d. assumption on the entries of in Theorem 5 and Corollary 2 may limit their applicability in genetic studies, where SNPs are often correlated due to linkage disequilibrium (LD). However, it is worth noting that the correlation among SNPs does not necessarily hinder the application of these results. This is because the theoretical guarantees rely on the validity of the Marchenko–Pastur law, which was originally established for random matrices with i.i.d. entries having a mean of zero and unit variance. Importantly, the i.i.d. assumption on the entries can be relaxed: the Marchenko–Pastur law still holds for random matrices with i.i.d. rows, as long as each row has a mean of zero and unit variance and satisfies a light tail condition (e.g., sub-Gaussian) [22]. Therefore, as long as the SNP vectors from each individual are i.i.d., we expect that the results in Theorem 5 and Corollary 2 remain valid.

2.3.2. Inner-Product Kernel Matrices

Inner-product kernels, including the linear kernel and the polynomial kernel, are commonly used in practice. Generally, an inner-product-based kernel matrix has the form . The first thing that needs to be addressed is the positive definiteness of . In fact, based on Hiai [23], a necessary and sufficient condition for to be positive definite is when f is real analytic and for all . In this subsection, we will implicitly assume that this condition is satisfied.

Theorem 6.

For with entries in and the function f,

- 1.

- .

- 2.

- are i.i.d. with , , and for some .

- 3.

- f is a function in the neighborhood of 1 and a function in the neighborhood of 0.

Then as as , we have

where is the true value for γ.

2.3.3. Euclidean Distance Kernel Matrices

Another commonly used kernels in practice are the Euclidean distance-based kernels, such as the Gaussian kernel. Similar to the case in the inner-product kernel matrices, the positive definiteness of is the first issue to be addressed. According to Wendland [24], f being completely monotone is a necessary and sufficient condition for a Euclidean distance kernel matrix to be positive semi-definite. In other words, the function f needs to satisfy and for all and . Throughout Section 2.3.3, it will be implicitly assumed that f is completely monotone.

Theorem 7.

Let be a kernel matrix with entries . Suppose that the entries in and the function f satisfying

- 1.

- .

- 2.

- are i.i.d. with , and for some .

- 3.

- f is a function in a neighborhood of 2.

Then as and , we have

where is the true value for γ.

Remark 1.

Both Theorems 6 and 7 rely on the approximation of inner-product kernel matrices or Euclidean distance kernel matrices by linear kernels, identity matrices, and some low-rank matrices. Based on the proofs in El Karoui [21], the approximation rate for inner-product kernel matrices is for some , while for a Gaussian kernel with entries with , the approximation rate is with being the rate that grows to infinity, and this is an extremely fast rate.

3. Results

3.1. Simulation Studies

3.1.1. Weighted Product Kernel

We follow an idea similar to that by Jiang et al. [11]; we simulated the genotype for each SNP. Specifically, the minor allele frequencies (MAFs) for p SNPs were generated from the uniform distribution , where is the allele for the jth SNP. In the simulation, the number of SNPs is set to . For the weight matrix , the jth element is defined to be

The logarithm of MAF, which was defined in Li et al. [25], is one of the commonly used weights to detect effects from common variants and also takes the contributions from rare variants into account. To simulate the genotype matrix , the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium was assumed. Specifically, for the j SNP, the genotype value of each individual was sampled from according to the probabilities , and , respectively. Given the simulated genotypes, column standardization was applied to each column in , and the resulting genotype matrix was denoted as . The weighted kernel matrix is defined as

The responses are simulated based on the following equation:

where the fixed-effect design matrix and the elements in were generated from a standard normal distribution. We set . The random effect , and the random noise . The choice of the variance component for the random effects is the same as in Jiang et al. [11] under their dense scenario. On the other hand, genetic data is often noisy, and the signal-to-noise ratio is low. To mimic the real situation, we set the variance of the random error to be two. In the simulation, we selected 100, 200, 400, 600, 800, and 1000 as the sample sizes. A total of 1000 Monte Carlo replications were conducted to evaluate the performance of the REML estimators for the variance components in the simulation model.

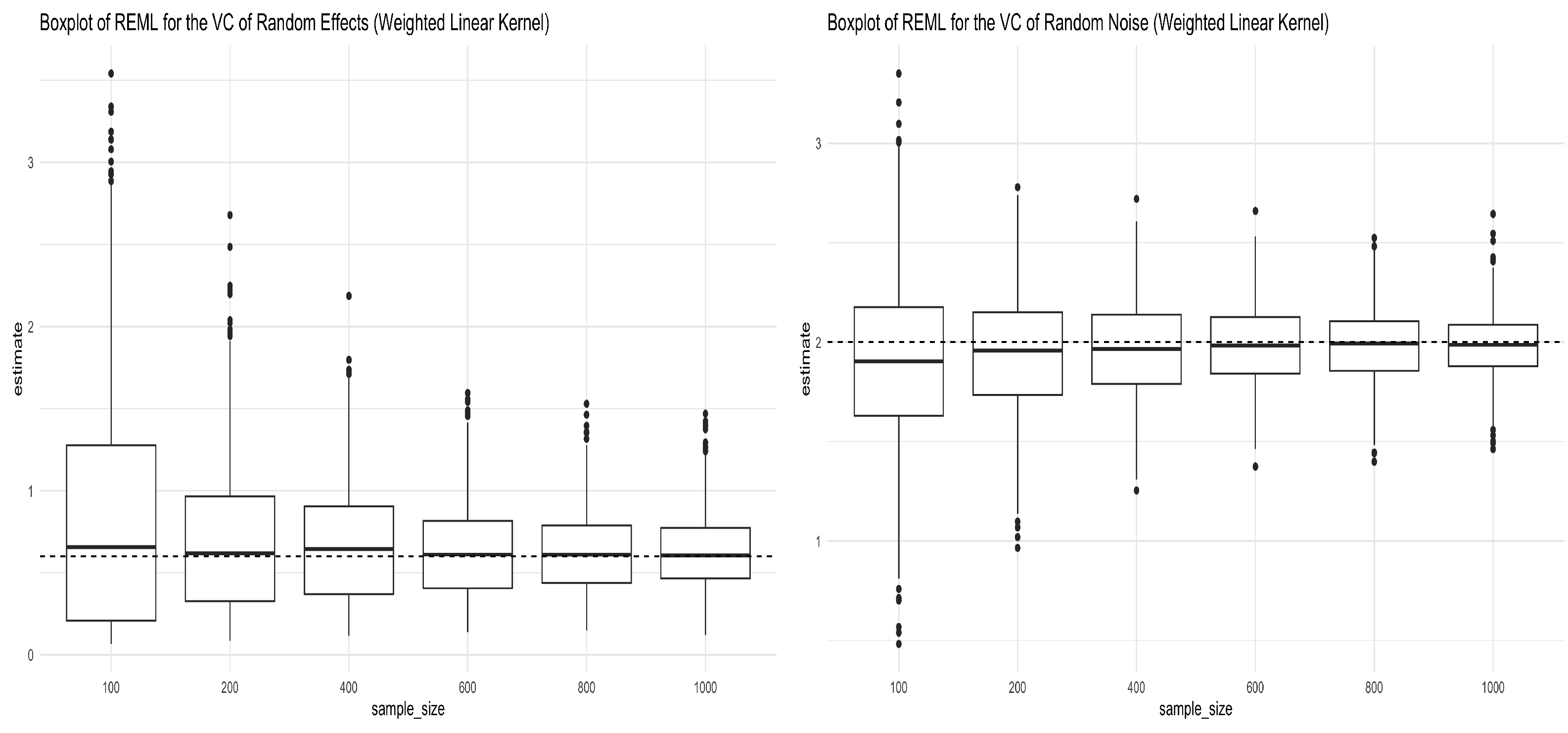

Figure 1 provides the boxplots for the REML estimators of the variance components in the simulation model (12). As shown from both panels, the REML estimators converge to the true values, which justifies the theoretical results developed in the previous sections. The mean and standard deviation of the REML estimators of the variance components are given in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Boxplots for REML estimators of variance components obtained from Simulation (12) under the weighted linear kernel. The left panel shows the boxplots for the REML estimator of (truth = 0.6), and the right panel shows the boxplots for the REML estimator of (truth = 2) under different sample sizes.

Table 1.

Mean and standard deviations (values in the parenthesis) of REML estimators for and based on 1000 Monte Carlo simulations under the weighted linear kernel.

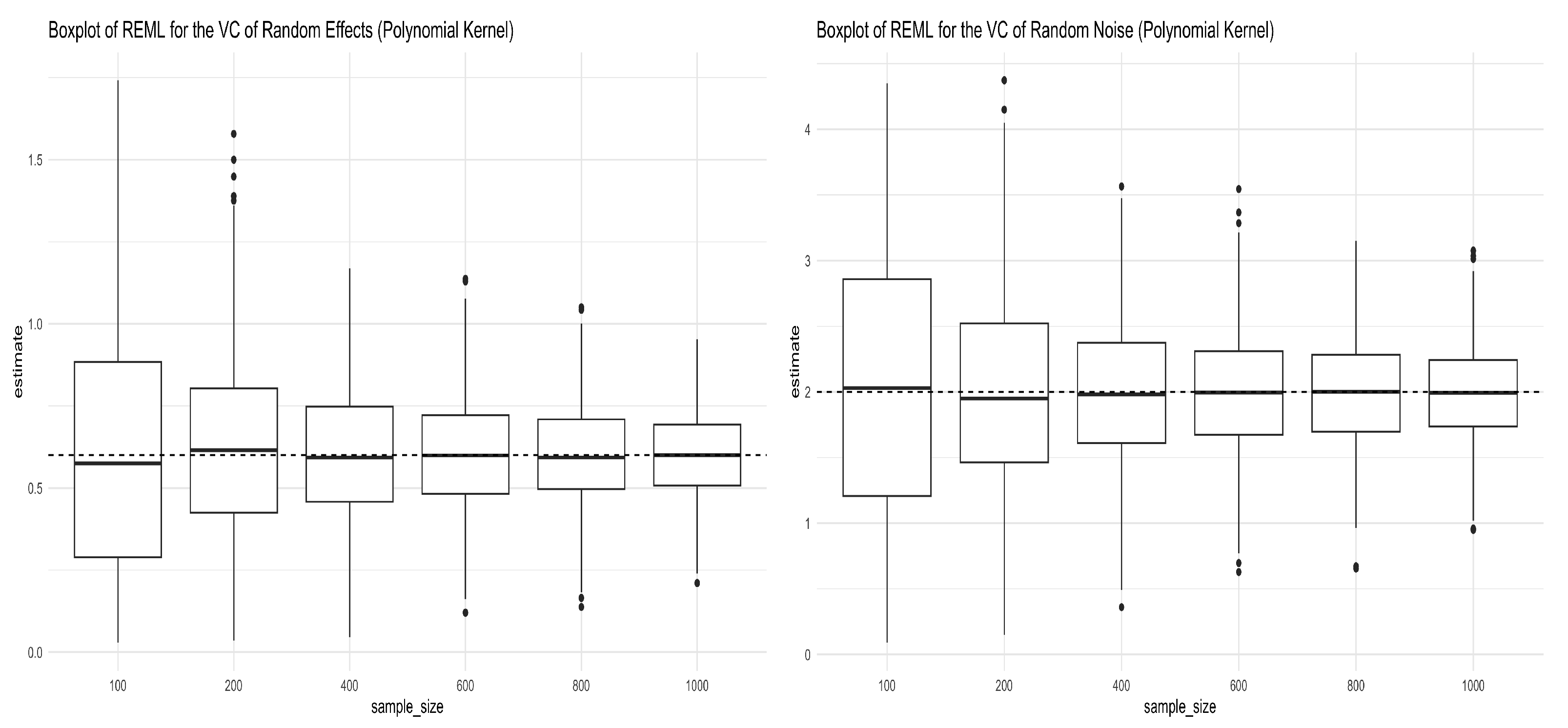

3.1.2. Inner Product Kernel

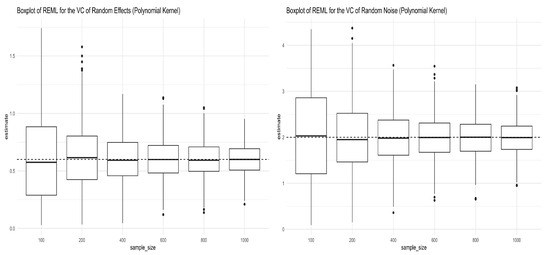

We followed the same procedures mentioned in Section 3.1.1 to simulate the genotype matrix , and Equation (12) was used to generate the response, except that in this case the kernel matrix is , with the polynomial kernel having an order of 2. In the expression, power means the elementwise power. Figure 2 shows the simulation results for the REML estimators of the two variance components in Equation (12). As we can see from both panels in Figure 2, the REML estimators converge to the true values as anticipated. The mean and standard deviation of the REML estimators of the variance components are given in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Boxplots for REML estimators of variance components obtained from Simulation (12) under the polynomial kernel with a degree of 2. The left panel shows the boxplots for the REML estimator of (truth = 0.6), and the right panel shows the boxplots for the REML estimator of (truth = 2) under different sample sizes.

Table 2.

Mean and standard deviations (values in the parenthesis) of REML estimators for and based on 1000 Monte Carlo simulations under the polynomial kernel with a degree of 2.

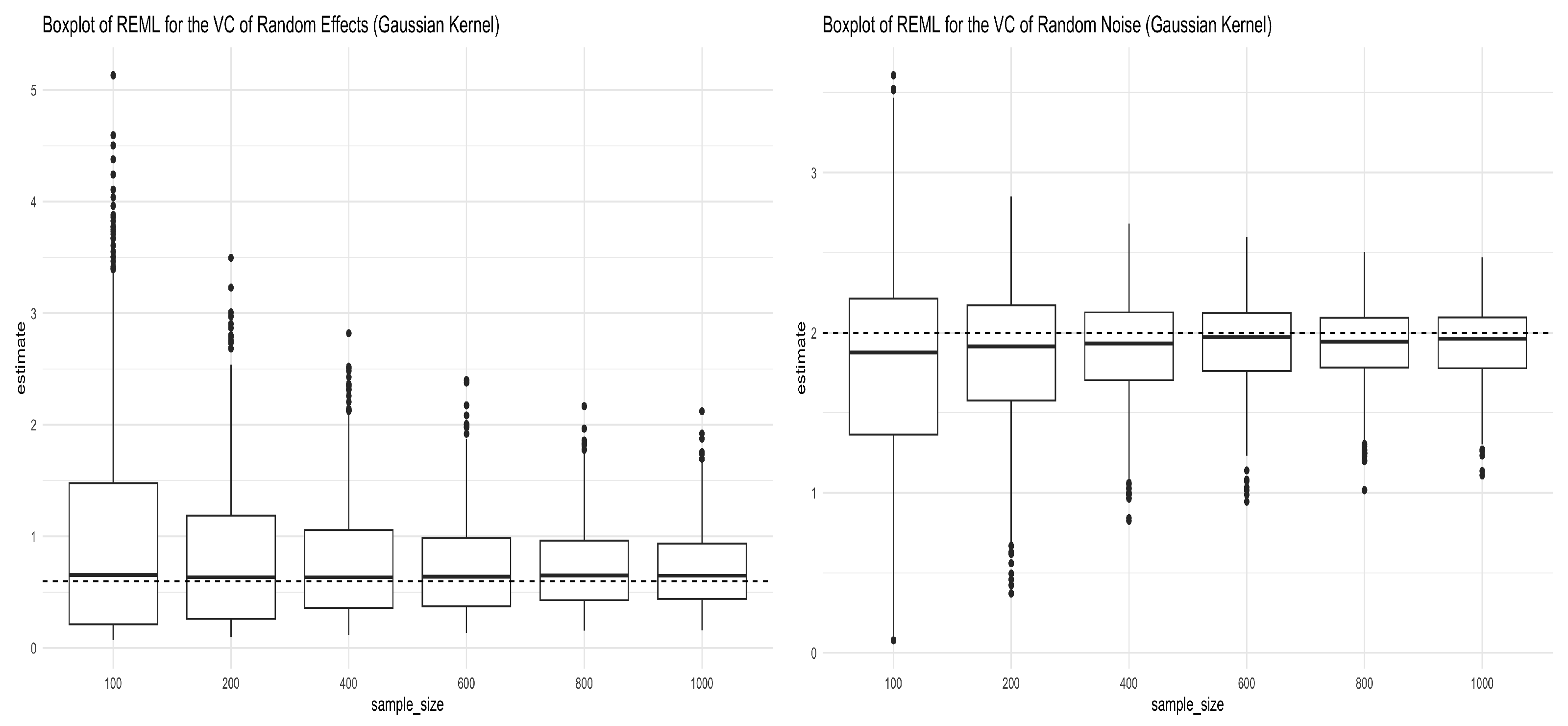

3.1.3. Euclidean Distance Kernel

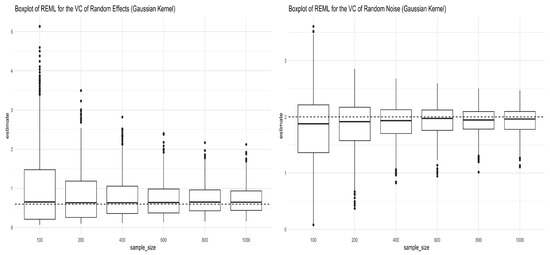

In this section, we investigated the consistency of REML estimators of the variance components when the kernel used to generate data in Equation (12) is the Gaussian kernel. When applying the Gaussian kernel , the tuning parameter is chosen to be the sample variance of the Euclidean distance between each pair. Figure 3 shows the simulation results for the REML estimators of the two variance components in Equation (12). The REML estimators converge to the true values as shown in both panels in Figure 3. The mean and standard deviation of the REML estimators of the variance components are given in Table 3.

Figure 3.

Boxplots for REML estimators of variance components obtained from Simulation (12) under the Gaussian kernel. The left panel shows the boxplots for the REML estimator of (truth = 0.6), and the right panel shows the boxplots for the REML estimator of (truth = 2) under different sample sizes.

Table 3.

Mean and standard deviations (values in parentheses) of REML estimators for and based on 1000 Monte Carlo simulations under the Gaussian kernel.

3.2. Real Data Analysis

To check the performance of Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML) estimators in high-dimensional kernel linear mixed models, we conducted a real data analysis similar to that by Jiang et al. [11]. The Study of Addiction: Genetics and Environment (SAGE) (dbGap Study Accession: phs000092.v1.p1) dataset was used to estimate the heritability of body mass index (BMI) based on kernel linear mixed models. To check the consistency of heritability estimation across different traits, we also include height and weight as the phenotypes.

After removing individuals without height or weight measures, a total of individuals of European ancestry remain. We also performed a quality control process similar to that by Jiang et al. [11] to avoid bias in the estimation. Specifically, SNPs with a missing rate of >1%, a minor allele frequency (MAF) of <5%, and a p-value of <0.001 from the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium test were excluded from the analysis. After the quality control process, p = 4,898,519 SNPs remained for analysis.

As in Jiang et al. [11], for the fixed-effect design matrix , besides the intercept, the first 10 principal component scores computed from the product kernels were included. Kernel LMMs with the product kernel , a second-order polynomial kernel, and a Gaussian kernel were used to estimate the variance components and hence the heritability. The results are summarized in Table 4. The heritability obtained by the linear kernel is 20.35%, which is very close to the one (19.6%) obtained in Jiang et al. [11]. It can be seen from the table that the heritability estimation of BMI is higher when the polynomial kernel or the Gaussian kernel with is used. The heritability obtained by the polynomial kernel is 50.08%, while the one obtained by the Gaussian kernel is 34.29%.

Table 4.

Heritability estimation for BMI, height, and weight under different kernel matrices.

It is believed that the BMI is highly heritable, and recent twin studies have demonstrated large variation in BMI heritability, ranging from 31% to 90% [26]. Based on the previous results, the heritability estimation obtained using the product kernel is below this range, while the estimations using the Gaussian kernel and the polynomial kernel are within this range. The trend that estimated heritability using the polynomial kernel is the highest among the three choices of kernel and is consistent among the other two phenotypes.

In addition, we also experimented with different values of the constant c in the polynomial kernel, ranging from 0 to 1. Table 5 summarizes the heritability estimates under these choices. The results show that the performance of heritability estimation is sensitive to the choice of kernel hyperparameters. In particular, Table 5 reveals a general pattern: as the value of c increases, the estimated heritability tends to decrease. One explanation is that so that the largest eigenvalue of the is lower bounded by , which means that when c becomes larger, the rank-one matrix dominates the spectrum of the polynomial kernel matrix. Consequently, the kernel matrix carries less informative structure for estimating the variance component in the random effects, resulting in a smaller estimate of .

Table 5.

Heritability estimation for BMI, height, and weight under different kernel matrices.

4. Discussion

Kernel methods have been widely used in machine learning to capture nonlinear relationships between features and responses. In this paper, we demonstrate that when kernels are correctly specified, the REML estimators for the variance components in high-dimensional kernel linear mixed models are consistent across three classes of kernel functions. Simulation studies validate the theoretical results on consistency.

In addition, we would like to highlight a few directions for future work. First, as we have mentioned, the consistency of the REML estimators for variance components in kernel LMMs is established under the assumption that the kernels are correctly specified. In practice, the underlying data-generating process and the appropriate kernel are often unknown. Misspecifying the kernel in a kernel LMM could lead to inconsistent variance component estimators, resulting in biased estimates of heritability. Therefore, it is worth exploring a data-driven approach to identify the appropriate kernel function and evaluate its performance in estimating genetic heritability compared to commonly used kernels.

Second, the theories in this paper are established under the high-dimensional linear regime, where the sample size grows linearly with the number of SNPs. One reason for this assumption is that random matrix theory is widely used to derive theoretical results, and most existing work in random matrix theory focuses on the linear regime. Therefore, it is worthwhile to extend random matrix theory beyond the linear regime. Recently, Ghorbani et al. [27] and Mei et al. [28] developed theories for random kernel matrices under the polynomial regime, where with . However, in genetic studies, the number of SNPs is often much larger than the sample size. Thus, it is worthwhile to extend the results in this paper to scenarios where and and to develop the corresponding theories for random kernel matrices under this regime.

Last but not least, as demonstrated in the real data analyses, the performance of kernel LMMs depends heavily on the choice of the kernel matrix. In practice, researchers often lack prior knowledge about which kernel is most appropriate. Therefore, developing a data-driven method for kernel selection would be highly desirable. One widely used strategy is multiple kernel learning [29], in which a single kernel matrix is replaced by a convex combination of several kernel matrices, where the weights of the kernel matrices are also learning by minimizing a loss function (e.g., mean squared error in the regression setting). Extending the current work to accommodate kernel matrices constructed via multiple kernel learning would be a valuable direction for future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.S. and Q.L.; methodology and formal analysis, X.S.; writing—original draft preparation, X.S.; writing—review and editing, Q.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The R code used for implementation can be found at https://github.com/SxxMichael/KernelLMM (accessed on 19 July 2025).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used ChatGPT 4o for the purposes of correcting grammatical mistakes. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Mathematical Proofs of the Main Results

Appendix A.1. Proof of Lemma 1

Proof.

Let and note that

we can obtain

Therefore,

□

Appendix A.2. Proof of Theorem 5

Proof.

Let . Then according to the well-known identity (see for example, Searle et al. [18]), we have

Therefore,

Under the assumptions of , we have , and hence

which further implies that

As a consequence,

where the last equality follows from Corollary 1.

Now we define

with

Next, we write , and we are going to show that converges to some constant limit, and . We first show that . Based on Lemma 1,

where and and are the corresponding matrices of and with the truth . We now consider each term in the right hand side of Equation (A1). First note that

Since

and it follows from the assumption on and Corollary 1,

we know that . On the other hand,

and since , it follows that

According to Corollary 1

which implies that .

For the second term, it is clear that

Since

we can know that .

Similarly for the third term, we have

Therefore, and by Chebyshev’s inequality, for any ,

It then follows from the Dominated Convergence Theorem that

which implies that .

Next, let us focus on . It is easy to see that

Since

it follows from Bounded Convergence Theorem that

Moreover, note that

and according to Theorem 2, the ESD of converges in distribution almost surely to a nonrandom distribution F. Let be the eigenvalues of , then

For notation simplicity, we define

Similarly, since , it follows from Bounded Convergence Theorem that

Moreover, note that

and by Theorem 2,

Let

Then we have

Using Fubini Theorem and some tedious algebra, it follows that

Note that since is non-increasing and is non-decreasing, we have for any

and hence

which implies that

that is, . Therefore, , which is a constant limit, and the limit is , , and when , , and , respectively. This proves the desired result as is the solution to , and hence .

Next, we prove the second part of this theorem. Let

First note that , so we have

Next, since , by continuous mapping theorem, we have

which implies that . Finally, since where , by the famous Hanson Wright inequality, for any ,

Note that

so we obtain

which implies that . □

Appendix A.3. Proof of Corollary 2

Proof.

For simplicity, let and . Then . Let . Now note that

Since , we have and

Combining all of these yields . On the other hand,

By Lemma 2.6 in Jiang et al. [11],

which implies that , and hence . Finally, since

and by Corollary 2.3 in Jiang et al. [11],

Therefore, we can bound the Levy’s distance between and by Corollary A.42 in Bai and Silverstein [19]:

Hence, the ESD of converges a.s. in distribution to the ESD of . On the other hand,

Thus, the ESD of converges a.s. in distribution to the ESD of , and the desired results in the corollary follows Theorem 5. □

Appendix A.4. Proof of Theorem 6

Proof.

We follow the same framework as in the proof of Theorem 5. Let

Based on Theorem A.43 in Bai and Silverstein [19], we have

The matrix will play a vital part in the remainder of the proof as it is easy to see that the LSD of converges in distribution a.s. to some nonrandom distribution function by Theorem 2. On the other hand, since the elements in are i.i.d. with and , it is easy to see that the elements in are still i.i.d. with a mean of 0 and unit variance. Moreover, since

we know that the LSD of also converges in distribution a.s. to some nonrandom distribution function, and we denote such distribution by F.

It can be seen from the proof of Theorem 5 that one major part of showing the result is to show that , and . The proof of is exactly the same arguments as in the proof of Theorem 5, so we focus on the other two quantities.

As a consequence of Theorem A.45 in Bai and Silverstein [19] and Theorem 3, we have

Moreover, it follows from Theorem A.43 in Bai and Silverstein [19] that

which implies that

Therefore,

which implies that . Similarly, note that

which implies that and hence

For , note that

which implies that , and hence

Therefore, and as in the proof of Theorem 5, it follows from Chebyshev’s inequality and Dominated Convergence Theorem that .

Similar to the proof of Theorem 5, we now focus on . Recall from Equation (A2) that

Note that

Combined with Equations (A3) and (A4), it is easy to see that converges to a constant limit. The remaining part of the proof follows the same statements as in the proof of Theorem 6, so it is omitted. □

Appendix A.5. Proof of Theorem 7

Proof.

Let and be as defined in Equation (10). Now let

By Theorem A.43 in Bai and Silverstein [19] and the triangle inequality for matrix rank, we have

On the other hand, as a consequence of Theorem A.45 in Bai and Silverstein [19] and Theorem 4,

Moreover, it follows from Theorem A.43 in Bai and Silverstein [19] that

which implies that

The remaining of the proof is the same as the proof of Theorem 3. □

References

- Macgregor, S.; Cornes, B.K.; Martin, N.G.; Visscher, P.M. Bias, precision and heritability of self-reported and clinically measured height in Australian twins. Hum. Genet. 2006, 120, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silventoinen, K.; Sammalisto, S.; Perola, M.; Boomsma, D.I.; Cornes, B.K.; Davis, C.; Dunkel, L.; De Lange, M.; Harris, J.R.; Hjelmborg, J.V.; et al. Heritability of adult body height: A comparative study of twin cohorts in eight countries. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 2003, 6, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yengo, L.; Vedantam, S.; Marouli, E.; Sidorenko, J.; Bartell, E.; Sakaue, S.; Graff, M.; Eliasen, A.U.; Jiang, Y.; Raghavan, S.; et al. A saturated map of common genetic variants associated with human height. Nature 2022, 610, 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Lee, S.H.; Goddard, M.E.; Visscher, P.M. GCTA: A tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 88, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Benyamin, B.; McEvoy, B.P.; Gordon, S.; Henders, A.K.; Nyholt, D.R.; Madden, P.A.; Heath, A.C.; Martin, N.G.; Montgomery, G.W.; et al. Common SNPs explain a large proportion of the heritability for human height. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 565–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Cai, T.T.; Li, H. Inference for high-dimensional linear mixed-effects models: A quasi-likelihood approach. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2022, 117, 1835–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Geer, S.; Bühlmann, P.; Ritov, Y.; Dezeure, R. On asymptotically optimal confidence regions and tests for high-dimensional models. Ann. Stat. 2014, 42, 1166–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.H.; Zhang, S.S. Confidence intervals for low dimensional parameters in high dimensional linear models. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. Stat. Methodol. 2014, 76, 217–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M.; Ritov, Y. Inference and estimation for random effects in high-dimensional linear mixed models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2023, 118, 1682–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.C.; Lee, S.; Cai, T.; Li, Y.; Boehnke, M.; Lin, X. Rare-variant association testing for sequencing data with the sequence kernel association test. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 89, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Li, C.; Paul, D.; Yang, C.; Zhao, H. On high-dimensional misspecified mixed model analysis in genome-wide association study. Ann. Stat. 2016, 44, 2127–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, C.; Jiang, J.; Paul, D.; Zhao, H. Variance estimation and confidence intervals from genome-wide association studies through high-dimensional misspecified mixed model analysis. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 2022, 220, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Jiang, W.; Paul, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, H. High-dimensional asymptotic behavior of inference based on gwas summary statistic. Stat. Sin. 2023, 33, 1555–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Lin, X.; Ghosh, D. Semiparametric regression of multidimensional genetic pathway data: Least-squares kernel machines and linear mixed models. Biometrics 2007, 63, 1079–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; Carlin, B.P.; Gelfand, A.E. Hierarchical Modeling and Analysis for Spatial Data; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, X.; Wen, Y.; Cui, Y.; Lu, Q. A conditional autoregressive model for genetic association analysis accounting for genetic heterogeneity. Stat. Med. 2022, 41, 517–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Los Campos, G.; Vazquez, A.I.; Fernando, R.; Klimentidis, Y.C.; Sorensen, D. Prediction of complex human traits using the genomic best linear unbiased predictor. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Searle, S.R.; Casella, G.; McCulloch, C.E. Variance Components; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; Volume 391. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Z.; Silverstein, J.W. Spectral Analysis of Large Dimensional Random Matrices; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 20. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, D.; Aue, A. Random matrix theory in statistics: A review. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 2014, 150, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Karoui, N. The spectrum of kernel random matrices. Ann. Stat. 2010, 38, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couillet, R.; Liao, Z. Random Matrix Methods for Machine Learning; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hiai, F. Monotonicity for entrywise functions of matrices. Linear Algebra Its Appl. 2009, 431, 1125–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendland, H. Scattered Data Approximation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; He, Z.; Zhang, M.; Zhan, X.; Wei, C.; Elston, R.C.; Lu, Q. A generalized genetic random field method for the genetic association analysis of sequencing data. Genet. Epidemiol. 2014, 38, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrempft, S.; van Jaarsveld, C.H.; Fisher, A.; Herle, M.; Smith, A.D.; Fildes, A.; Llewellyn, C.H. Variation in the heritability of child body mass index by obesogenic home environment. JAMA Pediatr. 2018, 172, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghorbani, B.; Mei, S.; Misiakiewicz, T.; Montanari, A. When do neural networks outperform kernel methods? Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 14820–14830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, S.; Misiakiewicz, T.; Montanari, A. Learning with invariances in random features and kernel models. In Proceedings of the Conference on Learning Theory, PMLR, Boulder, CO, USA, 15–19 August 2021; pp. 3351–3418. [Google Scholar]

- Gönen, M.; Alpaydın, E. Multiple kernel learning algorithms. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2211–2268. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).