Evidence for Language Policy in Government Pre-Primary Schools in Nigeria: Cross-Language Transfer and Interdependence

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Language Learning in Early Years Settings

1.2. Cross-Language Transfer in Early Year Settings

1.3. The Present Study

- Is there a correlation between phoneme and decoding scores in Hausa in early years settings in Nigeria?

- Is there a correlation between phoneme and decoding scores in English in early years settings in Nigeria?

- Are phoneme and decoding scores correlated between Hausa and English?

- As per the interdependence hypothesis, is there a bidirectional association between Hausa and English word/decoding scores?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Instruments

3. Results

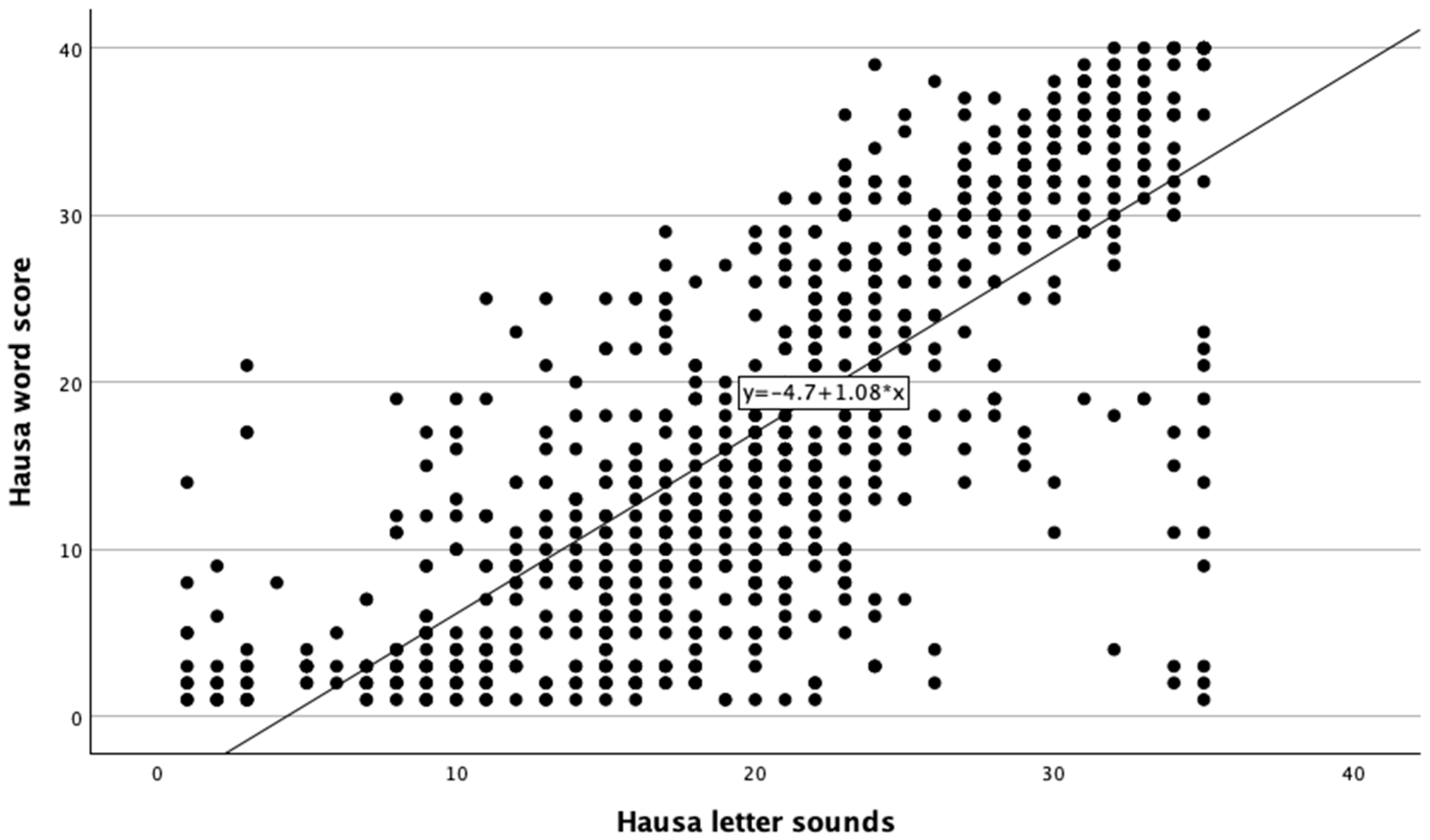

- Is there a correlation between phoneme and decoding scores in Hausa in early years settings in Nigeria?

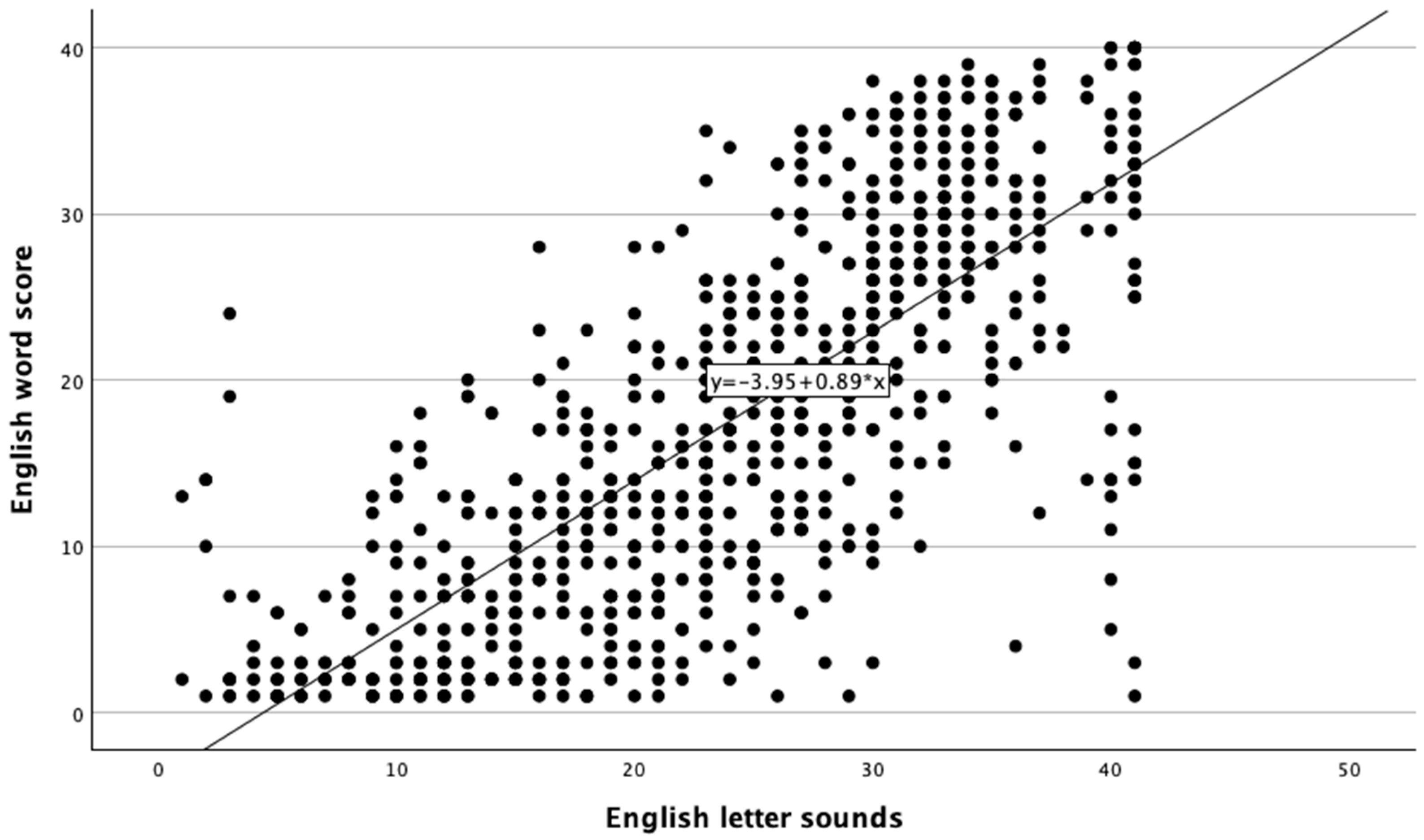

- Is there a correlation between phoneme and decoding scores in English in early years settings in Nigeria?

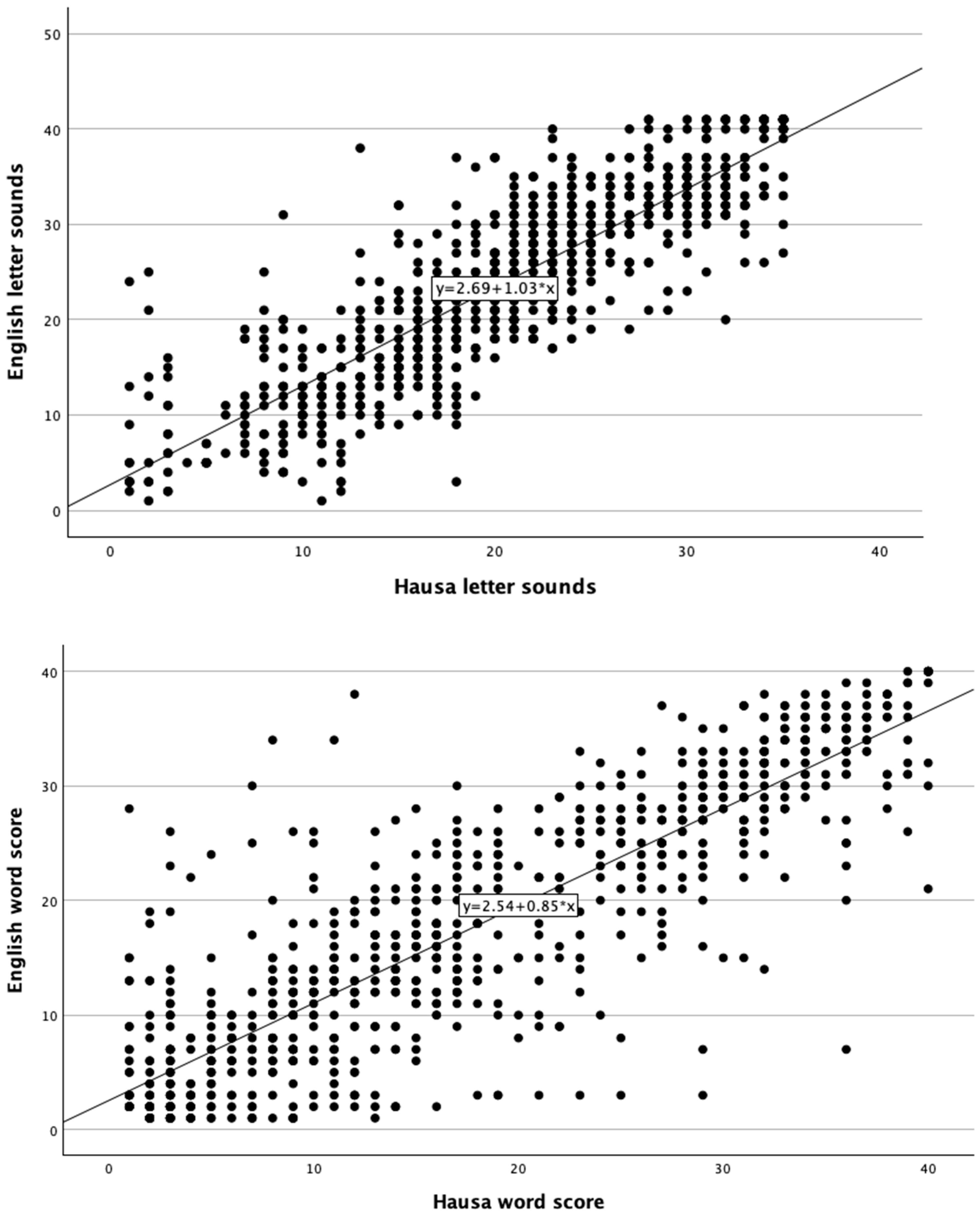

- Are phoneme and decoding scores correlated between Hausa and English?

- As per the interdependence hypothesis, is there a bidirectional association between Hausa and English word/decoding scores?

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NERDC | Nigerian Education Research and Development Council |

| NLP | National Language Policy |

| MT | Mother Tongue |

| ECCDE | Early Child Care Development Education |

| ECE | Early Childhood Education |

| FME | Federal Ministry of Education |

| LIC | Language of the Immediate Community |

| USAID | United States Agency for International Development |

| 1 | https://www.oed.com/discover/nigerian-english/ (accessed on 3 April 2025). |

References

- Abu-Rabia, S., & Siegel, L. S. (2002). Reading, syntactic, orthographic, and working memory skills of bilingual Arabic-English speaking Canadian children. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 31(6), 661–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apio, J., Williams, E. M., Adrupio, S., Acquah, S., & Lawson, L. (2024). Mapping early childhood development research outputs in sub-Saharan Africa: Uganda country report. REAL Centre, University of Cambridge and ESSA. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, D. L., Stoolmiller, M., Good, R. H., III, & Baker, S. K. (2011). Effect of reading comprehension on passage fluency in Spanish and English for second-grade English learners. School Psychology Review, 40(3), 331–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamgbose, A. (2000). Language and exclusion: The consequences of language policies in Africa. Lit Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein, M. H., Hahn, C. S., Putnick, F. L., & Suwalsky, J. T. (2014). Stability of core language skill from early childhood to adolescence: A latent variable approach. Child Development, 85, 1346–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branum-Martin, L., Tao, S., Garnaat, S., Bunta, F., & Francis, D. J. (2012). Meta-analysis of bilingual phonological awareness: Language, age, and psycholinguistic grain size. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(4), 932–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britto, P. R., Yoshikawa, H., & Boller, K. (2011). Quality of early childhood development programs in global contexts: Rationale for investment, conceptual framework, and implications for equity and commentaries. Social Policy Report, 25(2), 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, M., & Bell, M. A. (2022). Vocabulary and executive functioning: A scoping review of the unidirectional and bidirectional associations across early childhood. Human Development, 66(3), 167–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdenski, T. (2000). Evaluating univariate, bivariate, and multivariate Normality using graphical and statistical procedures. Multiple Linear Regression Viewpoints, 26, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Counihan, C., Humble, S., Gittins, L., & Dixon, P. (2022). The effect of different teacher literacy training programmes on student’s word reading abilities in government primary schools in Northern Nigeria. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 33(2), 198–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, J. (1976). The influence of bilingualism on cognitive growth: A synthesis of research findings and explanatory hypotheses (pp. 1–43). Working Papers in Bilingualism, No. 9. Ontario Institute for Studies in Education. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, J. (1979). Linguistic interdependence and the educational development of bilingual children. Review of Educational Research, 49(2), 222–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, J. (1981). The role of primary language development in promoting educational success for language minority students. In California State Department of Education (Ed.), Schooling and language minority students: A theoretical framework. California State University; Evaluation, Dissemination and Assessment Center. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, J. (1998). Immersion education for the millennium: What have we learned from 30 years of research on second language immersion? In M. R. Childs, & R. M. Bostwick (Eds.), Learning through two languages: Research and practice. Second Katoh Gakuen international symposium on immersion and bilingual education (pp. 34–47). Katoh Gakuen, Japan. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, J. (2001). Language, power and pedagogy: Bilingual children in the crossfire. Multilingual Matters Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, J. (2017). Teaching for Transfer in Multilingual School Contexts. In O. Garcia, A. M. Y. Lin, & S. May (Eds.), Bilingual and multilingual education (pp. 103–117). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- de Galbert, P. G. (2023). Language transfer theory and its policy implications: Exploring interdependence between Luganda, Runyankole-Rukiga, and English in Uganda. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 44(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, D. S., Greenop, K., & Fry, J. (2010). The effects of phonological awareness of Zulu-speaking children learning to spell in English: A study of cross-language transfer. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 80, 517–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DfID. (2018). DFID education policy get children learning. Department for International Development.

- Dixon, P., Schagen, I., & Seedhouse, P. (2011). The impact of an intervention on children’s reading and spelling ability in low-income schools in India. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 22(4), 461–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, F. J., Mengoni, S. E., Bailey, A. M., & Snowling, M. J. (2014). Validity and sensitivity of the phonics screening check: Implications for practice. Journal of Research in Reading, 38(2), 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, R. J., Anderson, K. L., King, Y. A., Finders, J. K., Schmitt, S. A., & Purpura, D. J. (2023). Predictors of preschool language environments and their relations to children’s vocabulary. Infant Child Development, 32, e2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durgunoğlu, A. Y. (2002). Cross-linguistic transfer in literacy development and implications for language learners. Annals of Dyslexia, 52, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finders, J., Wilson, E., & Duncan, R. (2023). Early childhood education language environments: Considerations for research and practice. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1202819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Partnership for Education. (2019). Leaving no one behind: A knowledge and innovation exchange. (KIX) Discussion Paper. Global Partnership for Education. [Google Scholar]

- Gravetter, F., & Wallnau, L. (2014). Essentials of statistics for the behavioural sciences (8th ed.). Wadsworth. [Google Scholar]

- Heine, B., & Nurse, D. (2000). African languages: An introduction. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hentges, R. F., Devereux, C., Graham, S. A., & Madigan, S. (2021). Child language difficulties and internalizing and externalizing symptoms: A meta-analysis. Child Development, 92, e691–e715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humble, S. (2020). Quantitative analysis of questionnaires: Techniques to explore structures and relationships. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Humble, S., Dixon, P., Gittins, L., & Counihan, C. (2024). An investigation of the cross-language transfer of reading skills: Evidence from a study in Nigerian Government Primary Schools. Education Sciences, 13(3), 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttenlocher, J., Vasilyeva, M., Cymerman, E., & Levine, S. (2002). Language input and child syntax. Cognitive Psychology, 45(3), 337–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igboanusi, H. (2006). A comparative study of the pronunciation features of Igbo English and Yoruba English speakers of Nigeria. English Studies, 87(4), 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegede, O. O. (2024). Evaluating the potential of a Unified Hausa-Igbo-Yoruba language to ease language related social and political conflicts in Nigeria. Journal of Universal Language, 25(2), 51–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D. A. (1979). Correlation and causality. John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.-S. G., & Piper, B. (2019). Cross-laguage transfer of reading skills: An empirical investigation of bidirectionality and the influence of instructional environment. Reading and Writing, 32, 839–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-S. G., Stern, J., Mohohlwane, N., & Taylor, S. (2025). Instruction influences cross-language transfer of reading skills: Evidence from a longitudinal randomized controlled trial. Reading and Writing, 38, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structured equation modelling (4th ed.). Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen, E. I. (2004). Sensitive periods in the development of the brain and behavior. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 16(8), 1412–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koda, K. (2007). Reading and language learning: Crosslinguistic constraints on second language reading development. Language Learning, 57(s1), 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loehlin, J. C., & Beaujean, A. A. (2017). Latent variable models. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Malah, Z., & Rashid, S. M. (2015). Contrastive analysis of the segmental phonemes of English and Hausa Languages. International Journal of Languages, Literature and Linguistics, 1(2), 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Manis, F. R., Lindsey, K. A., & Bailey, C. E. (2004). Development of reading in grades K–2 in Spanish- speaking English-language learners. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice, 19(4), 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

- NERDC. (2013). National policy on education: Federal Republic of Nigeria. NERDC (Nigerian Educational Research and Development Council).

- NERDC. (2022). National language policy. NERDC (Nigerian Educational Research and Development Council).

- Obiakor, T. E. (2024). Language of instruction policy in Nigeria: Assessing implementation and literacy achievement in a multilingual environment. International Journal of Educational Development, 109, 103108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohiri-Aniche, C. (2016). Marginalization of Nigerian languages in nursery & primary schools: Path to indigenous language death in Nigeria. In O.-M. Ndimele (Ed.), Nigerian languages, literatures, culture and reforms (6th ed., pp. 33–48). M & J Grand Orbit Communications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwafemi, O. L., Nma, A., Osita, O., & Olugbenga, O. (2014). Implementation of early childhood education: A case study in Nigeria. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 2(2), 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otheguy, R., Garcia, O., & Reid, W. (2015). Clarifying translanguaging and deconstruction named languages: A perspective from linguistics. Applied Linguistics Review, 6, 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otheguy, R., Garcia, O., & Reid, W. (2019). A translanguaging view of the linguistic system of bilinguals. Applied Linguistics Review, 19, 625–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, A., Alper, R., Burchinal, M. R., Golinkoff, R. M., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2019). Measuring success: Within and cross-domain predictors of academic and social trajectories in elementary school. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 46(1), 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P., Chatterjee Singh, N., & Torppa, M. (2024). Understanding the role of cross-language transfer of phonological awareness in emergent Hindi-English biliteracy acquisition. Reading Writing, 37, 887–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, C. P., August, D., Carlo, M. S., & Snow, C. (2006). The intriguing role of Spanish language vocabulary knowledge in predicting English reading comprehension. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(1), 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raikes, A., Koziol, N., & Burton, A. (2020). Measuring quality of pre-primary education in sub-Saharan Africa: Evaluation of the measuring early learning environments scale. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 53, 571–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rämä-Ory, P. (2022). Language acquisition in early years of childhood: The role of family and pre-primary education. Thematic Report Commissioned for the World Conference on Early Childhood Care and Education. UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Seid, Y. (2016). Does learning in mother tongue matter? Evidence from a natural experiment in Ethiopia. Economics of Education Review, 55, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skutnabb-Kangas, T., & Toukomaa, P. (1976). Teaching migrant children’s mother tongue and learning the language of the host country in the context of socio-cultural situation of the migrant family. The Finnish National Commission for UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Snow, C. E., Burns, M. S., & Griffin, P. (Eds.). (1998). Preventing reading difficulties in young children. National Academy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Snow, C. E., & Kim, Y.-S. (2007). Large problem spaces: The challenge of vocabulary for English language learners. In R. K. Wagner, A. E. Muse, & K. R. Tannenbaum (Eds.), Vocabulary acquisition: Implications for reading comprehension (pp. 123–139). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sooter, T. (2013). Early childhood education in Nigeria: Issues and problems. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 3(5), 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Spier, E., Dias, P., Ranjit, V., Rothbard, V., & Toungui, A. (2021). Evaluation of UNICEF early childhood development (ECD) programming in the eastern and southern Africa Region. American Institutes for Research. [Google Scholar]

- Standards and Testing Agency. (2012). Phonics screening check: 2012 technical report. Standards and Testing Agency. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a74caeded915d502d6cb0ca/Phonics_screening_check-2012_technical_report.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Tang, Y., Luo, R., Shi, Y., Xie, G., Chen, S., & Liu, C. (2023). Preschool or/and kindergarten? The long-term benefits of different types of early childhood education on pupils’ skills. PLoS ONE, 18(11), e0289614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tooley, J., Dixon, P., & Olaniyan, O. (2005). Private and public schooling in low-income areas of Lagos State, Nigeria: A census and comparative survey. International Journal of Educational Research, 43(3), 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trawick-Smith, J. (2005). Early childhood development: A multicultural perspective. Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Trudell, B., Piper, B., & Ralaingita, W. (2023). Language of instruction in the African classroom: Key issues, challenges and solutions. In R. M. Joshi, C. A. McBride, B. Kaani, & G. Elbeheri (Eds.), Handbook of literacy in Africa (Vol. 24, pp. 79–102). Literacy Studies. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, K. P., Anthony, A. B., Justice, L., & Bowles, R. (2009). Preschoolers’ exposure to language stimulation in classrooms serving at-risk children: The contribution of group size and activity context. Early Education and Development, 20(1), 53–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USAID. (2021). Final report, USAID soma umenye. U.S. Agency for International Development.

- Vaughn, S., Cirino, P. T., Linan-Thompson, S., Mathes, P. G., Carlson, C. D., Hagan, E. C., Pollard-Durodola, S. D., Fletcher, J. M., & Francis, D. J. (2006). Effectiveness of a Spanish intervention and an English intervention for English-Language learners at risk for reading problems. American Educational Research Journal, 43(3), 449–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veii, K., & Everatt, J. (2005). Predictors of reading among Herero–English bilingual Namibian school children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 8(3), 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Cheng, C., & Chen, S.-W. (2006). Contribution of morphological awareness to Chinese–English biliteracy acquisition. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(3), 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawire, B. A., & Kim, Y. S. G. (2018). Cross-language transfer of phonological awareness and letter knowledge: Causal evidence and nature of transfer. Scientific Studies of Reading, 22(6), 443–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L. (2018). Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Applied Linguistics, 39(1), 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolfolk, A., & Perry, N. E. (2012). Child and adolescent development. Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2010). Studies on experimental bilingual education in Senegal. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2019a). Ending learning poverty: What will it take? World Bank Group. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2019b). Equity and inclusion in education in World Bank projects: Persons with disabilities, indigenous peoples, and sexual and gender minorities. World Bank Group. [Google Scholar]

- Yopp, H. K. (1992). Developing phonemic awareness in young children. The Reading Teacher, 45(9), 696–703. [Google Scholar]

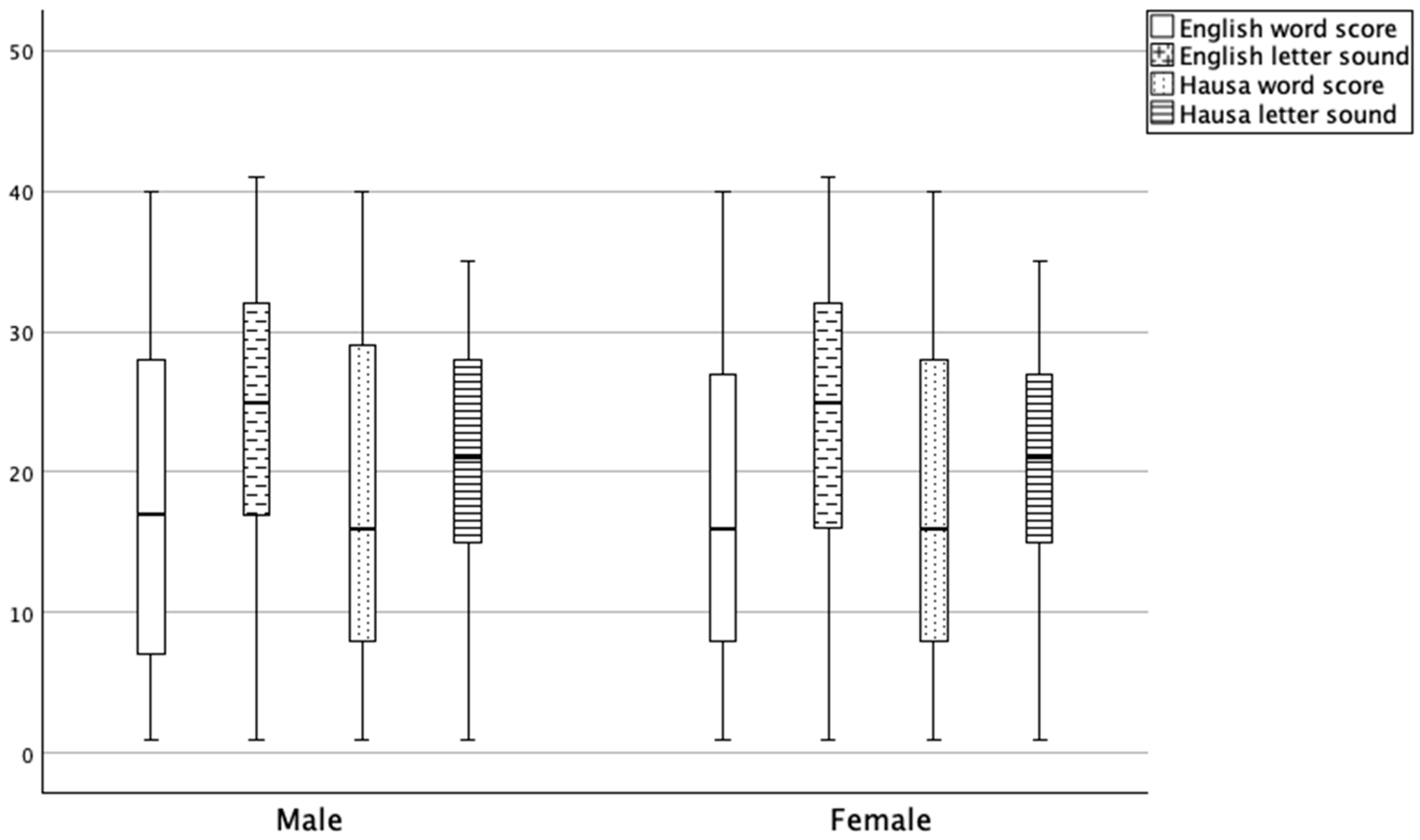

| Total Test Scores | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hausa Letter Sound (Phoneme) Knowledge | Hausa Word Reading Decoding | English Letter Sound (Phoneme) Knowledge | English Word Reading Decoding | |

| Total mean score (SD) | 20.65 (8.257) | 17.69 (11.712) | 24.06 (9.900) | 17.57 (11.467) |

| Male mean score (SD) | 20.96 (8.255) | 17.99 (11.832) | 24.33 (9.725) | 17.70 (11.838) |

| Female mean score (SD) | 20.35 (8.256) | 17.41 (11.602) | 23.80 (10.069) | 17.45 (11.113) |

| Total skewness | −0.236 | 0.262 | −0.230 | 0.194 |

| Total kurtosis | −0.571 | −1.198 | −0.802 | −1.177 |

| Hausa Scores (L1) | English Scores (L2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sounds (Phoneme) | Word Decoding | Sounds (Phoneme) | Word Decoding | |

| Hausa Sounds (Phoneme) (L1) | 1 | |||

| Hausa Word Decoding (L1) | 0.764 ** | 1 | ||

| English Sounds (Phoneme) (L2) | 0.863 ** | 0.738 ** | 1 | |

| English Word Decoding (L2) | 0.730 ** | 0.868 ** | 0.772 ** | 1 |

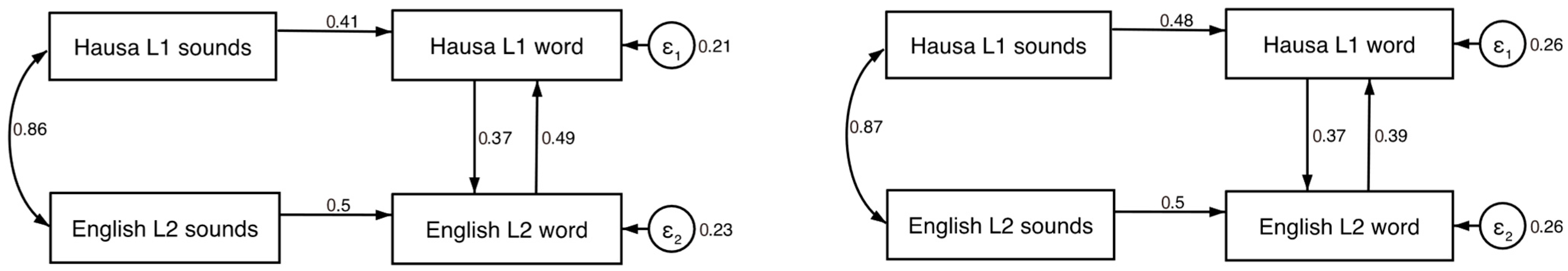

| Endogenous Variables | ||

|---|---|---|

| Exogenous Variables | L1 Word (Hausa) | L2 Word (English) |

| L1 phonemes (Hausa) | 0.441 *** (0.038) | |

| L1 word (Hausa) | 0.367 *** (0.053) | |

| L2 phonemes (English) | 0.504 *** (0.040) | |

| L2 word (English) | 0.446 *** (0.049) | |

| Endogenous Variables | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exogenous Variables | L1 Word (Hausa) | L2 Word (English) | Wald Test | |||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |||

| L1 sounds (Hausa) | Male | 0.410 *** (0.048) | χ2(1) = 0.548, p = 0.459 | |||

| Female | 0.478 *** (0.060) | |||||

| L1 word (Hausa) | Male | 0.369 *** (0.070) | χ2(1) = 0.015, p = 0.903 | |||

| Female | 0.373 *** (0.079) | |||||

| L2 sounds (English) | Male | 0.505 *** (0.054) | χ2(1) = 0.476, p = 0.490 | |||

| Female | 0.498 *** (0.060) | |||||

| L2 word (English) | Male | 0.489 *** (0.062) | χ2(1) = 0.585, p = 0.444 | |||

| Female | 0.394 *** (0.078) | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dixon, P.; Humble, S.; Gittins, L.; Seery, F.; Counihan, C. Evidence for Language Policy in Government Pre-Primary Schools in Nigeria: Cross-Language Transfer and Interdependence. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1197. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091197

Dixon P, Humble S, Gittins L, Seery F, Counihan C. Evidence for Language Policy in Government Pre-Primary Schools in Nigeria: Cross-Language Transfer and Interdependence. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1197. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091197

Chicago/Turabian StyleDixon, Pauline, Steve Humble, Louise Gittins, Francesca Seery, and Chris Counihan. 2025. "Evidence for Language Policy in Government Pre-Primary Schools in Nigeria: Cross-Language Transfer and Interdependence" Education Sciences 15, no. 9: 1197. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091197

APA StyleDixon, P., Humble, S., Gittins, L., Seery, F., & Counihan, C. (2025). Evidence for Language Policy in Government Pre-Primary Schools in Nigeria: Cross-Language Transfer and Interdependence. Education Sciences, 15(9), 1197. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091197