What Makes Adult Learners Persist in College? An Analysis Using the Nontraditional Undergraduate Student Attrition Model

Abstract

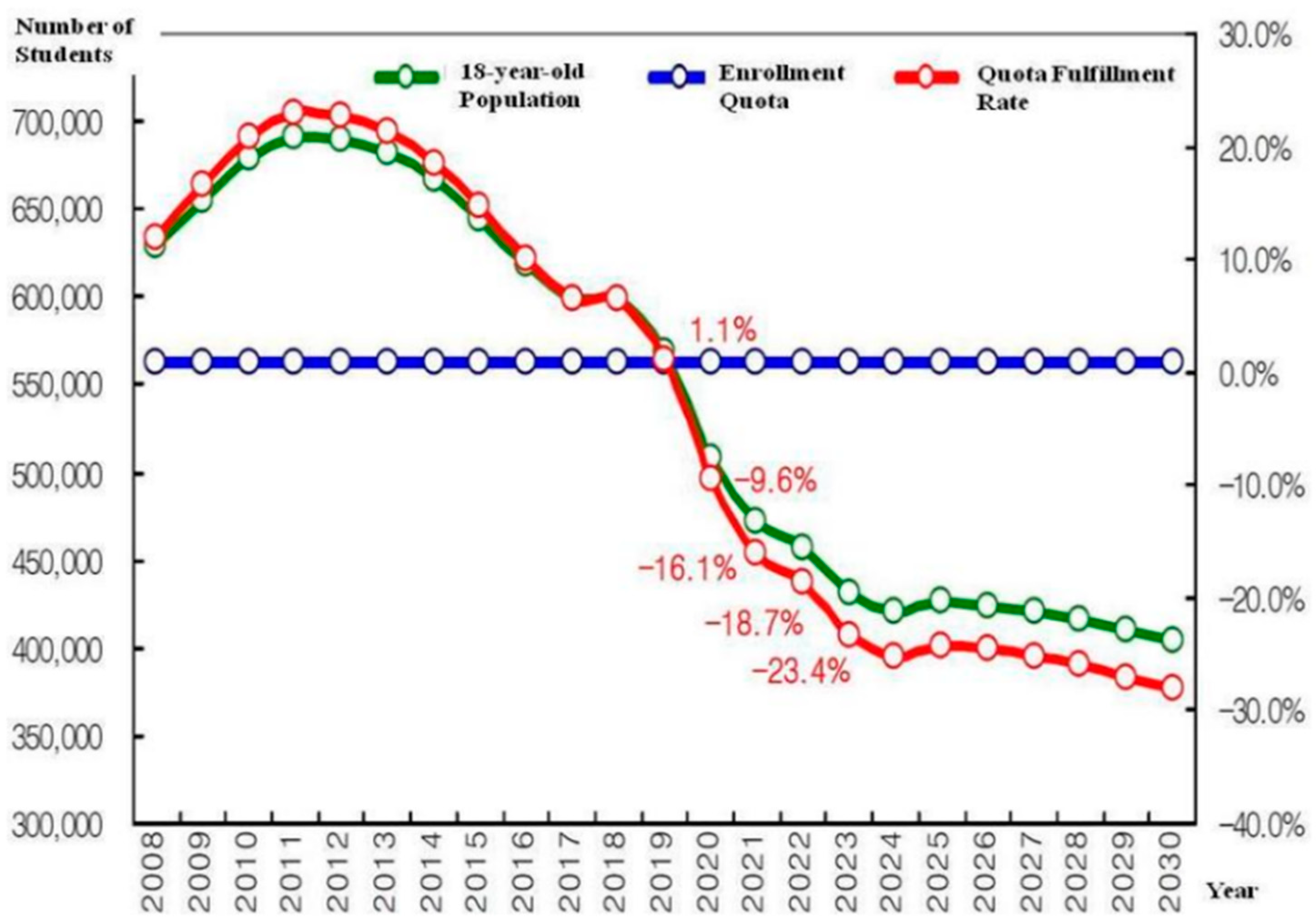

1. Introduction

2. Literature Reviews

2.1. Characteristics of Adult Learners

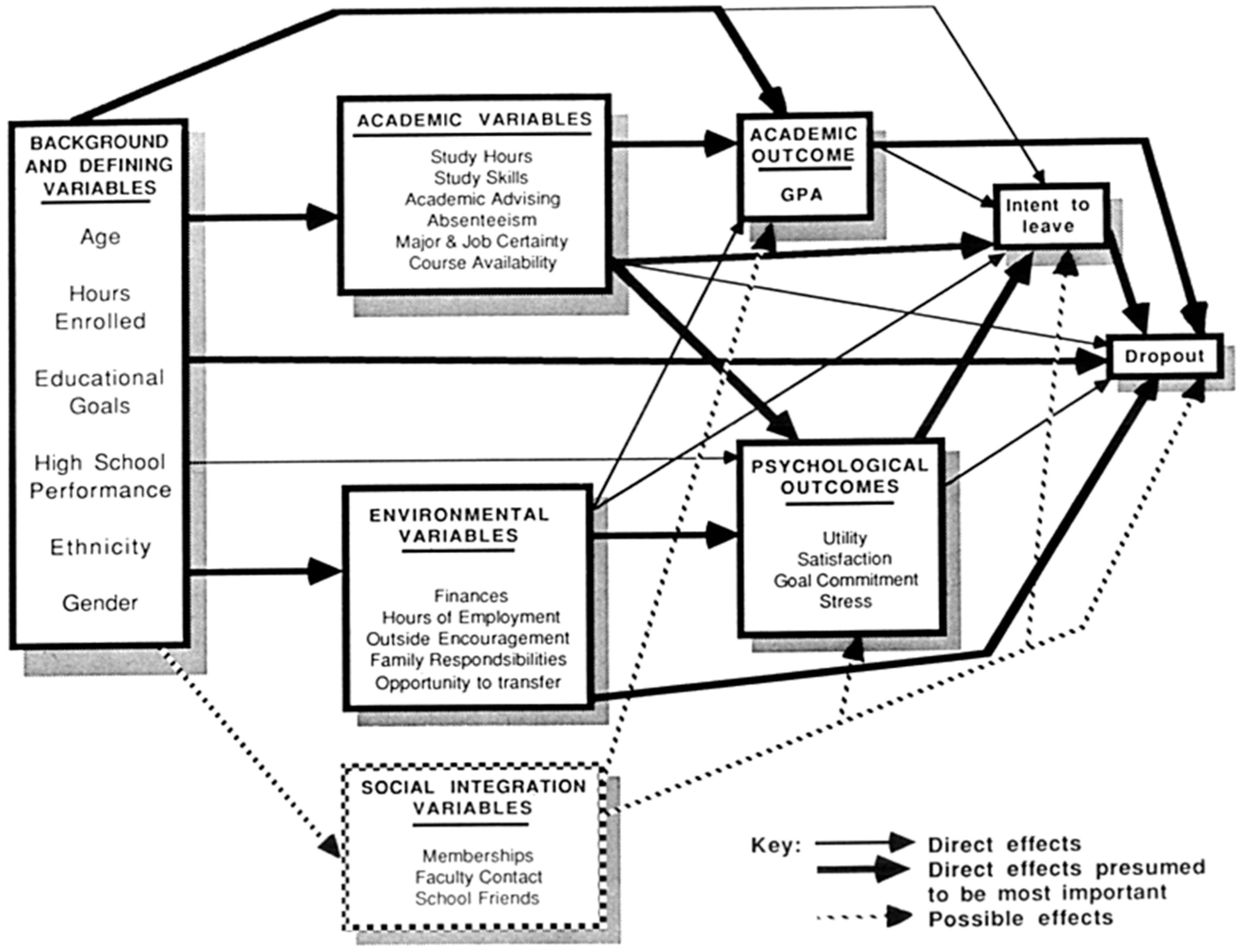

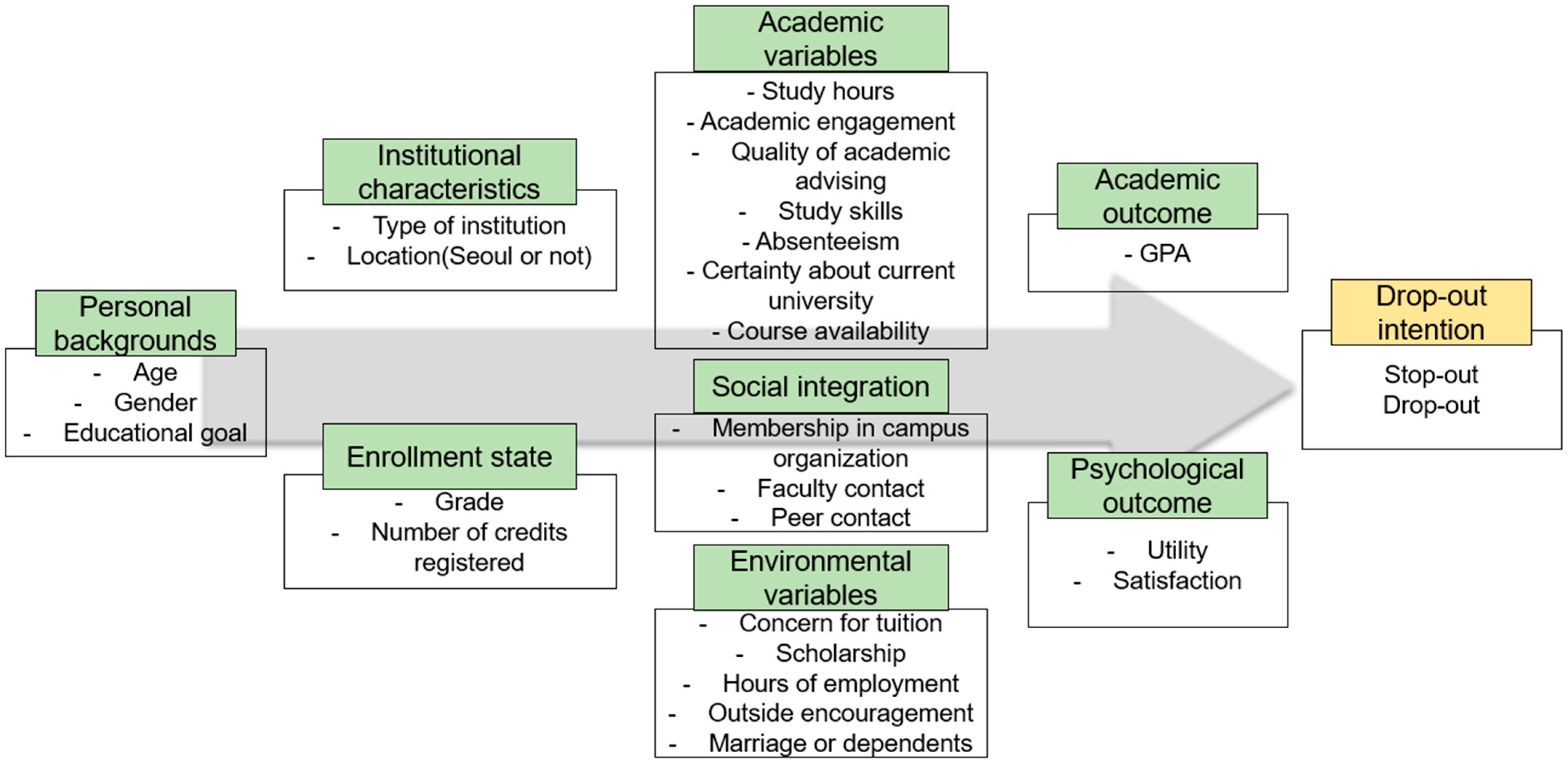

2.2. Theoretical Background About Student Attrition

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Description of Data

3.2. Measurement

3.3. Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Summary of Findings

5.2. Discussions for Both Stop-Out and Drop-Out

5.2.1. Academic Preparedness and Enrollment Status as a Common Factor

5.2.2. Role of Academic Advising and Institutional Support

5.2.3. Unique Patterns in Student Attrition Among Adult Learners

5.2.4. Limited Influence of Social Integration and Psychological Outcomes

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications and Suggestions for Furture Studeis

6.2. Practical Implications for Universities

6.3. Suggestions for Future Study

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

The Results of CFA and Reliability Test for Constructs

| Variable Name (Constructs) | Questions | Mean | SD | Factor Loading | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic variables | |||||

| Academic engagement | Asking questions during class. | 2.55 | 0.974 | 0.731 | 0.857 |

| Logically presenting one’s own opinions. | 2.94 | 1.000 | 0.802 | ||

| Evaluating whether information is trustworthy and of good quality. | 3.37 | 0.948 | 0.804 | ||

| Challenging oneself when encountering difficulties in studying. | 3.11 | 0.957 | 0.799 | ||

| Voluntarily practicing writing. | 2.48 | 1.039 | 0.635 | ||

| Searching for academic papers or scholarly materials. | 2.93 | 1.051 | 0.704 | ||

| Independently studying topics of personal interest. | 3.47 | 0.883 | 0.670 | ||

| Quality of academic advising | Professors show enthusiasm in educating students. | 3.38 | 0.782 | 0.953 | 0.899 |

| Professors value students’ classroom experiences and learning. | 3.48 | 0.746 | 0.953 | ||

| Study skills | I found classes and assignments difficult (reverse-coded) | 2.85 | 0.932 | 0.878 | 0.702 |

| I did not study as hard as I should have (reverse-coded) | 2.72 | 0.943 | 0.878 | ||

| Academic negligence | I skip classes without any reason. | 1.69 | 0.870 | 0.854 | 0.788 |

| I arrive late to class. | 1.75 | 0.857 | 0.852 | ||

| I submit assignments late. | 1.65 | 0.879 | 0.807 | ||

| Certainty about current university | I feel that I fit in well with the environment at this university. | 3.20 | 0.842 | 0.898 | 0.759 |

| I am satisfied with my decision to attend this university. | 3.45 | 0.863 | 0.898 | ||

| Social integration | |||||

| Faculty contact | “How often do you engage in the following activities with professors?”: Casual greetings | 3.35 | 1.853 | 0.843 | 0.950 |

| Brief conversations with professors. | 2.95 | 1.656 | 0.922 | ||

| Discussions or Q&A about class content. | 3.02 | 1.614 | 0.879 | ||

| Conversations about topics unrelated to class content. | 2.75 | 1.636 | 0.940 | ||

| Consultations on personal matters (e.g., academics, career planning). | 2.42 | 1.461 | 0.925 | ||

| Inquiries about grades. | 2.17 | 1.402 | 0.812 | ||

| Participation in department-related activities (e.g., preparing events). | 2.19 | 1.498 | 0.839 | ||

| Friend contact | “How often do you engage in the following activities with your peers?”: Consultations on personal matters (e.g., academics, career planning). | 2.84 | 1.674 | 0.902 | 0.962 |

| Study activities related to classes. | 2.98 | 1.692 | 0.886 | ||

| Learning activities outside of class. | 2.76 | 1.662 | 0.917 | ||

| Advice on school life. | 2.65 | 1.619 | 0.930 | ||

| Participation in department (school) events or gatherings. | 2.52 | 1.582 | 0.888 | ||

| Club or volunteer activities. | 2.37 | 1.624 | 0.831 | ||

| Outdoor activities or sports. | 2.41 | 1.596 | 0.881 | ||

| Recreational activities. | 2.51 | 1.666 | 0.883 | ||

| Environmental variables | |||||

| Parental involvement | Degree to which parents encouraged or engaged in the following areas of students’ college activities: Preparation for future career or further education. | 2.68 | 1.132 | 0.858 | 0.786 |

| Selection of courses. | 1.79 | 0.966 | 0.559 | ||

| Participation in extracurricular activities outside of one’s major or department. | 1.86 | 1.008 | 0.874 | ||

| Management of academic performance (GPA). | 2.25 | 1.108 | 0.836 | ||

| Psychological outcomes | |||||

| Utility | I have found clear reasons for attending this university and understand what I aim to achieve. | 3.45 | 0.847 | 0.900 | 0.762 |

| I find what I am learning at this university interesting and useful. | 3.32 | 0.748 | 0.900 | ||

| Satisfaction | Satisfaction with the overall quality of lectures | 3.34 | 0.883 | 0.909 | 0.943 |

| Satisfaction with faculty and instructors | 3.31 | 0.801 | 0.920 | ||

| Satisfaction with the structure of courses or curriculum | 3.31 | 0.785 | 0.905 | ||

| Satisfaction with teaching methods | 3.26 | 0.781 | 0.899 | ||

| Satisfaction with the overall educational environment | 3.29 | 0.803 | 0.862 | ||

| Satisfaction with interaction with professors | 3.17 | 0.887 | 0.809 | ||

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, C. (1992). Classrooms: Goals, structures, and student motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(3), 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K. T. (2011). Linking adult learner satisfaction with retention: The role of background characteristics, academic characteristics, and satisfaction upon retention. Iowa State University. [Google Scholar]

- Bean, J. P., & Metzner, B. S. (1985). A conceptual model of nontraditional undergraduate student attrition. Review of Educational Research, 55(4), 485–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellare, Y., Smith, A., Cochran, K., & Lopez, S. G. (2023). Motivations and barriers for adult learner achievement: Recommendations for institutions of higher education. Adult Learning, 34(1), 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, M., Gross, J. P. K., Berry, M., & Shuck, B. (2014a). If life happened but a degree didn’t: Examining factors that impact adult student persistence. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 62(2), 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, M. J. (2012). An examination of factors that impact persistence among adult students in a degree-completion program at a four-year university [Doctoral dissertation, University of Louisville]. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, M. J., Gross, J., Berry, T., & Schuck, D. (2014b). The theory of adult learner persistence in degree-completion programs. Adult Education Quarterly, 64(3), 233–250. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, A., & Bergman, M. (2016). Affordability and the return on investment of college completion: Unique challenges and opportunities for adult learners. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 64(3), 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braxton, J. M., Hirschy, A. S., & McClendon, S. A. (2004). Understanding and reducing college student departure (ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 30 (3)). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Bulotaitė, L., Sargautytė, R., Žukauskaitė, I., & Bagdžiūnienė, D. (2025). Study environment and psychological factors of university students’ intention to drop out. Acta Paedagogica Vilnensia, 53, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bye, D., Pushkar, D., & Conway, M. (2007). Motivation, interest, and positive affect in traditional and nontraditional undergraduate students. Adult Education Quarterly, 57(2), 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale, A. P., & Rose, S. J. (2015). The economy goes to college: The hidden promise of higher education in the post-industrial service economy. Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, U.-S. (2006). An analytical study on conditions and nature of adult learners’ participation for lifelong education. Journal of Lifelong Learning Society, 2(1), 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y. J., & Park, G. J. (2018). The study on the satisfaction of the education programs: Focus on adult learners at the lifelong education institutes of university. Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Society, 19(10), 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlan, O., Grabowski, S., & Smith, K. (2003). Adult learning. In M. Orey (Ed.), Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology. The University of Georgia. [Google Scholar]

- Deschacht, N., & Goeman, K. (2015). The effect of blended learning on course persistence and performance of adult learners: A difference-in-differences analysis. Computers & Education, 87, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, J. F., & Graham, S. W. (1999). A model of college outcomes for adults. Adult Education Quarterly, 50(1), 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. (2024). Adult learning—Participants. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Adult_learning_-_participants (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Fuhrmann, B. S. (1997). Philosophies and aims. In J. G. Gaff, & J. L. Ratcliff (Eds.), Handbook of the undergraduate curriculum: A comprehensive guide to purposes, structures, practices and change (pp. 86–99). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, A. C., Maietta, H. N., Gardner, P. D., & Perkins, N. (2022). Postsecondary adult learner motivation: An analysis of credentialing patterns and decision making within higher education programs. Adult Learning, 33(1), 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Commission on the Futures of Education. (2021). Reimagining our futures together: A new social contract for education. UNESCO Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, H. (2019). Exploring the factors affecting participation intention of work-learning parallel adult learners in continuing education: Focusing on the structural relationship between normative beliefs, motivation to comply, and attitudes. Journal of Lifelong Learning Society, 15(2), 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, C.-G., Bae, E. K., & Park, S. O. (2018). Mediating effects of self-directed learning ability on the relationship between types of learning participation motivation and level of learning flow of adult learners in a distance university. Journal of Education & Culture, 24(5), 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, M., Erdoğdu, F., Kokoç, M., & Çağıltay, K. (2019). Challenges faced by adult learners in online distance education: A literature review. Open Praxis, 11(1), 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasworm, C. E. (2003). Adult meaning making in the undergraduate classroom. Adult Education Quarterly, 53(2), 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I. (2022). Competency of adult learners at lifelong education system of university. The Journal of Education Consulting & Coaching, 6(2), 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. M. (2017). Phenomenological approach to the meaning of learning experience on adult learners in distance university. The Journal of Educational Research, 15(1), 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y. M., & Han, S. H. (2012). A structural analysis of adult learner’s self-concept, participation motivation and degree of participation in learning on lifelong learning outcomes. CNU Journal of Educational Studies, 33(2), 123–143. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, M. S. (1980). The modern practice of adult education: From pedagogy to andragogy (2nd ed.). Cambridge Books. [Google Scholar]

- Ku, J. H., Han, S. H., & Kang, H. (2015). A structural analysis of adult learners’ lifelong education consciousness, participation motivation, and learning outcome. Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Society, 16(7), 4537–4548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K.-S. (2013). Government policy and internationalisation of universities: The case of international student mobility in South Korea. Journal of Contemporary Eastern Asia, 12(1), 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S. A., Kim, M. J., Seo, H. J., & Kim, M. J. (2020). A logistic regression analysis on dropout of adult learners in distance higher education. Lifelong Learning Society, 16(4), 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., & Hong, S. (2022). A study on the diagnostic assessment of basic competency for adult learners. Korean Journal of Adult Continuing Educational Study, 13(4), 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyz, N. A., & Gladkaya, E. V. (2024). Lifelong learning in multi-purpose activity of self-employed and employed persons. Integration of Education, 28(2), 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzner, B. S., & Bean, J. P. (1987). The estimation of a conceptual model of nontraditional undergraduate student attrition. Research in Higher Education, 27(1), 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moges, B. T., Assefa, Y., Tilwani, S. A., Desta, S. Z., & Shah, M. A. (2023). The inclusion of indigenous knowledge into adult education programs: Implications for sustainable development. Studies in the Education of Adults, 56(1), 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, E. C., Park, S. W., & Kim, G. Y. (2024). A keyword network analysis of university lifelong education systems: Focusing on the promising practices of lifelong education for the future education (LiFE). CNU Journal of Educational Studies, 45(2), 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Survey of Student Engagement. (2013). NSSE 2013 survey instrument. Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research. [Google Scholar]

- Nemtcan, E., Sæle, R. G., Gamst-Klaussen, T., & Svartdal, F. (2020). Drop-out and transfer-out intentions: The role of socio-cognitive factors. Frontiers in Education, 5, 606291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2021). Education at a glance 2021: OECD indicators. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-H., & Choi, H. J. (2009). Factors influencing adult learners’ decision to drop out or persist in online learning. Educational Technology & Society, 12(4), 207–217. [Google Scholar]

- Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (1980). Predicting persistence and voluntary dropout decisions from a theoretical model. Journal of Higher Education, 51(1), 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P. R., Smith, D. A. F., García, T., & McKeachie, W. J. (1991). A manual for the use of the motivated strategies for learning questionnaire (MSLQ). National Center for Research to Improve Postsecondary Teaching and Learning, The University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Preuss, M. D., Bennett, P. J., Renner, B. J., & Wanstreet, C. E. (2023). The factors influencing retention of online adult learners: A case study of a private institution. International Journal of Research in Education and Science, 9(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, B. S. (2021). Linking higher education with lifelong education: Problems and solutions. Educational Research Tomorrow, 34(3), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter-Williams, D., & Rouse, R. A. (2011). Psychosocial issues and sources of support affecting retention for adult learners: Generational variations. Adult Education Research Conference. [Google Scholar]

- Ross-Gordon, J. M. (2011). Research on adult learners: Supporting the needs of a student population that is no longer nontraditional. Peer Review, 13(1), 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, J. W., & Kim, J. Y. (2024, February). University spots left open as Korea’s young population diminishes. Korea JoongAng Daily. Available online: https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/ (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Sheeran, P. (2002). Intention—Behavior relations: A conceptual and empirical review. European Review of Social Psychology, 12(1), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M., Jung, C., & Woo, H. (2020). A study on effect of learner characteristics for adult learners in distance university on learning outcome: Centered on mediating effect of motivation and impeding factors in learning participation. Journal of Lifelong Learning Society, 16(3), 177–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogunro, O. A. (2015). Motivating factors for adult learners in higher education. International Journal of Higher Education, 4(1), 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, H., & Kaufman, G. (2005). Degree completion among nontraditional college students. Social Science Quarterly, 86(4), 912–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tinto, V. (2012). Completing college: Rethinking institutional action (1st ed.). University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Urban, K., & Jirsáková, J. (2022). Motivation and personality traits in adult learners. Journal of Adult and Continuing Education, 28(1), 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Commerce, Census Bureau. (2022). Current population survey (CPS), October 2022. Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps.html (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Wlodkowski, R. J. (2003). Accelerated learning in colleges and universities. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 2003(97), 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., & Jung, J. (2019). Development of learning process and learning outcomes scale for adult learners in distance university. Journal of Education & Culture, 25(1), 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H. S., Lim, H. N., Choi, J. Y., Seo, Y. I., Shin, H. S., Ko, J. W., & Heo, E. (2012). National assessment of student engagement in learning for Korean universities (III) (Research Report RR2012-17). Korean Educational Development Institute. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Institution type | Community college | 64 | 21.7 |

| 4-year University | 231 | 78.3 | |

| Age | 27 | 210 | 71.2 |

| 29 | 85 | 28.8 | |

| Attending periods | 1 year | 74 | 25.1 |

| 2 years | 112 | 38.0 | |

| 3 years | 68 | 23.1 | |

| 4 years | 41 | 13.9 | |

| Employment status | Employed | 146 | 49.5 |

| Not employed | 149 | 50.5 | |

| Marital status | Married/living with partner | 17 | 5.8 |

| Not married | 278 | 94.2 | |

| Total | 295 | 100.0 | |

| Variable Name | Measurement | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | |||

| Drop-out intentions | |||

| Stop-out intention | 5 Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree~5 = strongly agree) for “I am thinking about leaving college for a while and finishing my degree program later” | 2.31 | 1.162 |

| Drop-out intention | 5 Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree~5 = strongly agree) for “I want to drop out” | 2.16 | 1.070 |

| Independent variables | |||

| Personal backgrounds | |||

| Age | Birth age, 0 = age 27, 1 = age 29 | 0.29 | 0.454 |

| Gender | 0 = female, 1 = male | 0.42 | 0.495 |

| Educational goal | Desired degree: 0 = undecided, 1 = high school~5 = PhD | 2.57 | 1.602 |

| Institutional characteristics | |||

| Type of institution | 0 = community college, 1 = 4-year institution | 0.78 | 0.413 |

| Location | 0 = not Seoul province, 1 = Seoul province | 0.53 | 0.500 |

| Enrollment state | |||

| Grade | Number of years attending current institution | 2.26 | 0.987 |

| Number of credits registered | Number of credits registered this semester: 0 = 0 credits, 1 = 1 to 5 credits, 2 = 6 to 10 credits, 3 = 11 to 15 credits, 4 = 16 to 20 credits, 5 = 21 or more credits | 2.77 | 1.940 |

| Academic variables | |||

| Study hours | 8 Likert scale (1 = never~9 = more than 21 h per week) for “Use time for Study” | 3.58 | 1.969 |

| Academic engagement | Mean of 7 questions such as “asking questions in the class” measured by 5 Likert scale (1 = never~5 = always) | 2.98 | 0.720 |

| Quality of academic advising | Mean of 2 questions such as “Professors are enthusiastic about the education of students” measured by 5 Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree~5 = strongly agree) | 3.43 | 0.728 |

| Study skills | Mean of 2 recoded questions such as “Classes and assignments felt difficult” measured by 5 Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree~5 = strongly agree) | 1.70 | 0.728 |

| Academic negligence | Mean of 3 questions such as “skip classes for no reason” measured by 5 Likert scale (1 = never~5 = always) | 2.79 | 0.823 |

| Certainty about current university | Mean of 2 questions such as “I am satisfied with the decision to attend my current university” measured on 5 Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree~5 = strongly agree) | 3.32 | 0.766 |

| Course availability | 5 Likert scale: “There are various courses that students want” measured by 5 Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree~5 = strongly agree) | 3.16 | 0.929 |

| Social integration | |||

| Membership in campus organization | Use time for campus organization measured by 9 Likert scale (1 = “never”~9: “more than 21 h per week”) | 1.42 | 0.948 |

| Faculty contact | Mean of 6 questions such as “How often do you exchange greeting with professors?” measured on 6-point scale (1 = “never”, 2 = “once or twice per semester”, 3 = “once or twice per month”, 4 = “once a week”, 5 = “two or three times a week”, 6 = “almost every day”) | 2.69 | 1.400 |

| Friend contact | Mean of 6 questions such as “How often do you have conversations about personal matters with friends?” measured on 6-point scale (1 = “never”, 2 = “once or twice per semester”, 3 = “once or twice per month”, 4 = “once a week”, 5 = “two or three times a week”, 6 = “almost every day”) | 2.63 | 1.459 |

| Environmental variables | |||

| Concern for tuition | “I feel anxiety over tuition fees” measured by 5 Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree”~5 = “strongly agree”) | 2.03 | 0.951 |

| Scholarship | 0 = no scholarship in the previous semester, 1 = earn scholarship in the previous semester | 0.27 | 0.444 |

| Hours of employment | Working hours per week measured on 7-point scale (0 = “none”, 1 = “up to 10 h”, 2 = “up to 20 h”, 3 = “up to 30 h”, 4 = “up to 40 h”, 5 = “up to 50 h”, 6 = “more than 50 h”) | 2.19 | 2.332 |

| Parental involvement | Mean of 4 questions such as “Parental involvement in course selection” measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “hardly involved at all”~5 = “highly involved”) | 2.04 | 0.943 |

| Marital status | 0 = “not married”, 1 = “married” | 0.03 | 0.181 |

| Academic outcome | |||

| GPA | Average grade level | 3.20 | 0.992 |

| Psychological outcomes | |||

| Utility | Mean of 2 questions such as “I found out why I am attending college and what I want to get” measured on 5 Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree”~5 = “strongly agree”) | 3.38 | 0.718 |

| Satisfaction | Mean of 6 questions such as “satisfaction with the quality of class” measured on 5 Likert scale (1 = “very dissatisfied”~5 = “very satisfied”) | 3.28 | 0.720 |

| DV: Stop-Out | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Variables | B | s.e | β | ||

| (Constant) | 3.376 *** | 0.989 | ||||

| Personal backgrounds | Age | 0.095 | 0.204 | 0.037 | ||

| Gender | - | −0.313 | 0.167 | - | −0.129 | |

| Educational goal | 0.001 | 0.053 | 0.002 | |||

| Institutional characteristics | Type of institution | 0.351 | 0.208 | 0.119 | ||

| Location | - | −0.056 | 0.176 | - | −0.023 | |

| Enrollment state | Grade | 0.008 | 0.091 | 0.006 | ||

| Number of credits registered | - | −0.210 *** | 0.057 | - | −0.253 | |

| Academic variables | Study hours | - | −0.090 | 0.048 | - | −0.147 |

| Academic engagement | 0.070 | 0.138 | 0.042 | |||

| Quality of academic advising | - | −0.336 * | 0.148 | - | −0.206 | |

| Academic negligence | 0.020 | 0.113 | 0.013 | |||

| Study skills | - | −0.334 ** | 0.108 | - | −0.225 | |

| Certainty about current university | 0.329 * | 0.143 | 0.215 | |||

| Course availability | 0.171 | 0.099 | 0.140 | |||

| Social integration | Membership in campus organization | - | −0.035 | 0.086 | - | −0.030 |

| Faculty contact | 0.167 | 0.100 | 0.184 | |||

| Friend contact | 0.007 | 0.093 | 0.009 | |||

| Environmental variables | Scholarship | - | −0.177 | 0.170 | - | −0.072 |

| Concern for tuition | 0.144 | 0.088 | 0.115 | |||

| Hours of employment | 0.066 | 0.043 | 0.128 | |||

| Parental involvement | 0.149 | 0.090 | 0.119 | |||

| Marital status | 0.662 | 0.449 | 0.097 | |||

| Academic outcome | GPA | - | −0.081 | 0.100 | - | −0.071 |

| Psychological outcome | Utility of college education | - | −0.112 | 0.156 | - | −0.069 |

| Satisfaction about college education | - | −0.092 | 0.174 | - | −0.059 | |

| R2 = 0.379, adjusted R2 = 0.283 | ||||||

| DV: Drop out | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Variables | B | s.e | β | ||

| (Constant) | 3.981 *** | 0.816 | ||||

| Personal backgrounds | Age | 0.222 | 0.168 | 0.098 | ||

| Gender | 0.006 | 0.138 | 0.003 | |||

| Educational goal | 0.008 | 0.043 | 0.011 | |||

| Institutional characteristics | Type of institution | 0.063 | 0.172 | 0.024 | ||

| Location | - | −0.212 | 0.145 | - | −0.102 | |

| Enrollment state | Grade | 0.029 | 0.075 | 0.028 | ||

| Number of credits registered | - | −0.103 * | 0.047 | - | −0.143 | |

| Academic variables | Study hours | - | −0.128 ** | 0.039 | - | −0.239 |

| Academic engagement | 0.108 | 0.113 | 0.075 | |||

| Quality of academic advising | - | −0.184 | 0.122 | - | −0.129 | |

| Academic negligence | 0.060 | 0.093 | 0.044 | |||

| Study skills | - | −0.272 ** | 0.089 | - | −0.210 | |

| Certainty about current university | 0.010 | 0.118 | 0.007 | |||

| Course availability | 0.036 | 0.081 | 0.034 | |||

| Social integration | Membership in campus organization | - | −0.064 | 0.071 | - | −0.063 |

| Faculty contact | 0.117 | 0.082 | 0.147 | |||

| Friend contact | 0.062 | 0.077 | 0.085 | |||

| Environmental variables | Scholarship | - | −0.260 | 0.140 | - | −0.122 |

| Concern for tuition | 0.055 | 0.072 | 0.050 | |||

| Hours of employment | 0.008 | 0.035 | 0.018 | |||

| Parental involvement | 0.194 ** | 0.074 | 0.179 | |||

| Marital status | 0.257 | 0.371 | 0.043 | |||

| Academic outcome | GPA | - | −0.201 * | 0.083 | - | −0.201 |

| Psychological outcome | Utility of college education | - | −0.129 | 0.129 | - | −0.092 |

| Satisfaction about college education | 0.053 | 0.144 | 0.039 | |||

| R2 = 0.442, adjusted R2 = 0.356 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, I. What Makes Adult Learners Persist in College? An Analysis Using the Nontraditional Undergraduate Student Attrition Model. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1085. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091085

Lee I. What Makes Adult Learners Persist in College? An Analysis Using the Nontraditional Undergraduate Student Attrition Model. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1085. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091085

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Inseo. 2025. "What Makes Adult Learners Persist in College? An Analysis Using the Nontraditional Undergraduate Student Attrition Model" Education Sciences 15, no. 9: 1085. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091085

APA StyleLee, I. (2025). What Makes Adult Learners Persist in College? An Analysis Using the Nontraditional Undergraduate Student Attrition Model. Education Sciences, 15(9), 1085. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091085