Abstract

A greater understanding of health-promoting factors, such as hope, is crucial for preventing and enhancing the mental health of higher education students. The Herth Hope Index (HHI) is a 12-item tool that has been widely used to assess a comprehensive, non-temporal perception of hope. While this instrument has been used extensively in adult populations, most studies focus on clinical populations. Additionally, the HHI reveals inconsistencies in terms of scale dimensionality and items to be retained. Therefore, this study sought to assess the HHI’s psychometric characteristics in a sample of Portuguese Higher Education students. The person response validity, internal scale validity, unidimensionality, and uniform differential item functioning were assessed using a Rasch rating scale model. A total of 2227 higher education students participated during the e-survey activation period (spring semester of 2020). The mean age of the sample was 22.5 ± 6.2 years (range 18–59 years). Three of the twelve items (#3, #5, and #6) failed to satisfy the established criterion for goodness of fit. Following the elimination of these three items, the resultant nine-item scale exhibited satisfactory item fit to the model, appropriate unidimensionality (52.4% of the variance explained), enough person goodness of fit, sufficient separation, and the absence of differential item functioning. The 9-item version of the HHI had psychometric properties comparable to the original 12-item version. This study also underscores the importance of validated instruments for assessing hope-based interventions in academic contexts. Further research is necessary to explore the potential dimensions inherent to the hope concept and to identify variations in hope profiles among items influenced by cultural attributes.

1. Introduction

In 2020, humanity faced a pandemic crisis due to the COVID-19 disease and its associated social impact, especially on the experience of young adults. Several studies report activities aimed at preventing the spread of the disease, with repercussions on so-called traditional education, even university education (J. Viana et al., 2023; Laranjeira et al., 2021a). Millions of students experienced a different reality, given the need for confinement and, for this reason, their separation from common spaces for socializing and learning (Mishra et al., 2020; J. Viana et al., 2023). The change in functional patterns in the general population’s way of life, particularly in young adults, has been associated with their mental health: stress, anxiety, depression, gratitude, and resilience (Lama & Ahad, 2023; Neu et al., 2024; Yotsidi et al., 2023); and increased prevalence of mental disorders with an impact on quality of life (Soldato et al., 2023).

The emergence of positive psychology has led to an increasing number of scholars investigating the influence of positive psychological attributes on mental well-being (Xiao et al., 2021). Hope was inversely related to loneliness, depression, and stress in university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. High levels of hope were associated with lower levels of these mental health symptoms (Strayhorn, 2023). The presence of hope, a significant positive psychological attribute, can mitigate the adverse consequences of psychological instability in secondary school students when they encounter stressful situations. It empowers them to handle their concerns in school and life with a more optimistic approach, thereby effectively safeguarding and enhancing their mental well-being (Nooripour et al., 2021; Laranjeira et al., 2021a). Individuals who possess a strong sense of hope tend to have a more optimistic outlook on the future. Additionally, those with greater psychological resilience are equipped with more positive psychological resources to cope with significant life events. This resilience helps diminish negative emotions that are futile and devoid of meaning, leading to an enhanced sense of life satisfaction, and serves as a protective factor for mental health (Laranjeira et al., 2021b, 2023; Schwander-Maire et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2023).

Gasper et al. (2020) proposed that hope and optimism might be seen as two measures of a singular dimension associated with future orientation. These two constructions share similarities but have fundamental differences. Hope focuses on the journey towards achieving desired goals, while optimism pertains to the overall expectation of positive future outcomes and the positive mindset in perceiving and understanding situations and events (Laranjeira & Querido, 2022). Larsen et al. (2020) showed that these two components are interdependent. Positive emotions, like hope, become more important when a person makes predictions about how to deal with obstacles (Velez et al., 2024). On the other hand, negative feelings, like hopelessness, become more important when a person’s forecasts indicate the situation is unmanageable (Farran et al., 1995; Laranjeira et al., 2021b). A limited number of measures are used to assess hope, specifically in terms of its relationship to oneself and others.

The Herth Hope Index (HHI) has been widely used for measuring hope (Herth, 1992). The HHI is a 12-item tool created to assess a comprehensive, non-temporal perception of hope. The HHI is derived from a description of hope defined as a multidimensional dynamic life force (with contextual [includes personal experiences of the whole life and they are under the influence of the experience of hope]; temporal [a relation between the past, present and future and hope], affiliative [relationship with oneself, with the others and with the Sacred], behavioral [actions taken to make hope come true], affective [emotions related to hope], and cognitive [thoughts and desires related to hope] dimensions) marked by a confident yet uncertain anticipation of attaining a future benefit, which is both realistically feasible and personally meaningful to the hopeful individual (Dufault & Martocchio, 1985). Collectively, these dimensions form the processes of hope. The HHI encompasses three dimensions: temporality and future, positive readiness and expectation, and connection (Herth, 1992). This scale has been translated and adapted for use in various populations, including the general population (Chan et al., 2012; Hirano et al., 2007; Robles-Bello & Sánchez-Teruel, 2023), individuals with chronic illness (Sartore et al., 2010; Rustøen et al., 2018), people with mental illness (Van Gestel-Timmermans et al., 2010), older people (Yaghoobzadeh et al., 2019), and individuals who have attempted suicide (Sánchez-Teruel et al., 2020). While this instrument has been extensively used in adult populations (Redlich-Amirav et al., 2018), most studies focus on clinical populations. Thus, there is a need to study and validate the HHI for non-clinical samples, namely with university students. Additionally, the HHI reveals inconsistencies in terms of scale dimensionality and items to be retained. Each scale validation exhibits a distinct structure when compared to the original version. This suggests challenges in the structure based on the population and the adaptation sample. Furthermore, there is a lack of research assessing the psychometric characteristics of this scale within the general Portuguese population, and there has been no examination of its invariance based on gender or age within this population. The measure’s invariance ensures that the assessment instruments accurately measure the same concept, independent of the characteristics of the individuals or groups being assessed (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002; Robles-Bello & Sánchez-Teruel, 2023). Lastly, the Rasch model was chosen as the methodological approach for this investigation because it is more suited for evaluating the psychometric features of a scale using ordinal data. Most of the previous validation studies of the HHI did not utilize this model.

Therefore, this study aims to assess the HHI’s psychometric characteristics in a sample of Portuguese Higher Education students using Rasch modeling.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A quantitative methodological study was developed, guided by Streiner and Norman’s recommendations (Streiner & Norman, 2008; Streiner & Kottner, 2014). This study is part of wider international research on the mental health of higher education students during a pandemic (Laranjeira et al., 2021a). We followed the International Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) (Mokkink et al., 2010).

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

Both convenience and snowball sampling methods were used to ensure comprehensive data collection of Portuguese Higher Education students from five educational institutions. Considering the practical limitations of time, resources, and accessibility, we intentionally employed a combination of convenience and snowball sampling methods to enhance our study’s outreach and efficiency (Kelley et al., 2003). Eligible participants were required to be at least 18 years old, possess an education level beyond high school, and have proficiency in reading and understanding Portuguese. We excluded incoming international students in mobility due to language barriers. The sample size calculation was based on a population of 41,000 students. For a confidence interval of 95% and a margin of error of 5% (most conservative scenario), a minimum of 381 participants would be necessary.

2.3. Data Collection and Instruments

This cross-sectional, web-based survey was conducted during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring semester of 2020. The e-survey link, granting access to the online survey, was disseminated using institutional email lists provided by the communication offices of the participating universities. The researchers also sent the link to their personal networks (Facebook, X social media, WhatsApp). To prevent duplications or fraud, responders were mandated to complete a CAPTCHA test, and cookies were employed to identify repeated responses.

The data collection instrument included two parts:

(1) Participants’ personal information: age, gender, area of study, past or present positive diagnosis for SARS-CoV-2.

(2) Herth Hope Index (HHI). We used the Portuguese version of HHI (translated and content-validated version) proposed by A. Viana et al. (2010). This scale measures hope using 12 Likert-type items (1 = completely disagree; 4 = completely agree) (Robles-Bello & Sánchez-Teruel, 2023). The original study found the scale has adequate psychometric properties (alpha Cronbach = 0.97; test–retest = 0.91) and a three-dimensional structure: temporality and the future (items 1, 2, 6 and 11); preparation (items 4, 7, 10 and 12); and positive expectations and interconnection (items 3, 5, 8 et 9). The scale has an overall score ranging from 12 to 48. A higher score indicates a higher level of hope. Items 3 and 6 are reversed (Herth, 1992). The HHI has been widely translated and psychometrically tested in many languages across numerous countries. A systematic review conducted by Nayeri et al. (2020) found that the HHI is one of the most widely translated and psychometrically tested tools worldwide, but psychometric variations in factor solutions remain inconsistent.

2.4. Ethics

The protocol received approval from the Ethics Committee of the Universidade Católica Portuguesa (approval n° 74) and the Ethics Committee of the Polytechnic University of Leiria (CE/IPLEIRIA/22/2020). Participants’ names and any other identifying information were not gathered. The research was carried out in compliance with the ethical guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants received the necessary information to provide informed consent regarding their participation in the study (before responding to the online questionnaire). They were informed about the variables and the main goals of the research.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive and inferential statistics were used. Various procedures were undertaken in the Rasch analysis to attain model adequacy, encompassing overall fit indices (e.g., MNSQ Item Outfit, MNSQ Item Infit); item and person fit parameters; threshold order for all items; the unidimensionality assessment; the assumption of local independence among items; and differential item functioning (DIF) (Tennant & Conaghan, 2007). DIF analysis was used to examine the stability of response patterns of the HHI questions concerning various demographic characteristics, hence aiding the assessment of validity regarding internal structure and potential bias in testing.

The Rasch model fundamentally necessitates unidimensionality. For an item to qualify as unidimensional, it must assess a singular construct (Bond & Fox, 2015). A Wright map (Boone, 2016), based on the Rasch rating scale model, was used to indicate the overall efficacy of the scale and the Infit mean square error for each item, which must be less than 1.5 to satisfy the criteria of the Rasch model (Bond et al., 2020). Conversely, the Rasch rating scale model offers a comprehensive analysis of individual scores, including the Outfit mean square error, which must be below 2.0 to conform to the standards of the Rasch model (Linacre, 2002).

The scale’s reliability was assessed by determining its internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha. Each item was evaluated by computing the adjusted item–total correlations and Cronbach’s alpha (α) upon item removal. Cronbach’s alpha levels beyond 0.9 indicate item redundancy, values ranging from 0.70 to 0.90 represent acceptable internal consistency, values between 0.50 and 0.69 reflect poor internal consistency, and values below 0.50 denote inadequate internal consistency (Hair et al., 2019).

A principal components analysis of each scale was performed using the varimax rotation method. The objective of this analysis was to reduce the data and determine the minimum number of principal components necessary to explain the maximum variance of the observed variables. Exploratory factor analysis was performed to examine the 12 questions covering more than one dimension.

We used the R language with the JAMOVI interface and the snowIRT library (package) to adjust the Rasch model to the data with the maximum marginal likelihood estimation method—Marginal Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MMLE) (Seol, 2023). The difNLR library (package) was used to perform the DIF (differential item function) analysis. Non-uniform DIF for ordinal data was detected using a cumulative logit regression model and likelihood ratio chi-square statistics.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

During the survey’s activation time, we obtained 2227 valid responses. The mean age of the sample was 22.5 ± 6.2 years (range 18–59 years). Most of the participants were female (79.6%), and 0.9% were diagnosed positive for SARS-CoV-2 (Table 1). In the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, this low rate of SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis was justified by multiple uncertainties in terms of virus origin, infection transmission roots and diagnostic tests.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of participants’ background (n = 2227).

3.2. Rasch Analysis

A preliminary Rasch analysis was conducted to assess the compatibility of the observed data with the Rasch model. The overall fit findings corroborated the non-significant chi-square test.

3.2.1. Item Bias/Differential Item Functioning (DIF)

Differential item functioning is used to ascertain whether an item assesses a latent concept uniformly across diverse populations (Linacre, 2013). No uniform DIF occurs when differences in response options are inconsistent across the trait being measured. This is addressed by removing the item from the Rasch model. This study assessed DIF analysis regarding sex and age group. No items exhibited probability values beyond the adjusted alpha level when age was taken into account. However, Items 3 (I feel alone), 5 (I have a faith that gives me comfort) and 6 (I feel scared about my future) demonstrated significant DIF (p < 0.001) in relation to sex. As the existence of DIF negatively impacts the quality of the measurement, those three items were removed.

The remaining nine items demonstrated good item fit for sex and age group (p > 0.05), as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Differential item functioning of the HHI items, after removing items #3, #5 and #6 from the Rasch model.

3.2.2. HHI Unidimensionality

Unidimensionality denotes the premise that the aggregated items collectively constitute a unidimensional scale. The principal component analysis indicated the residual values of this study were <0.267. Principal component analysis revealed that 52.4% of total variance was explained by the Rasch dimension, exceeding the recommended cut-off of 40% (Linacre, 2006), and a one-factor solution for the HHI was identified with an eigenvalue of 4.71.

Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (X2(36) = 8414, p < 0.001), and the KMO measure of sample adequacy was 0.923. The data corroborated that the measure is unidimensional and appropriate for research. In the analysis, the assumptions of principal component analysis were met: communalities had values greater than 0.3 (Hair et al., 2019).

3.2.3. Internal Consistency Reliability

To evaluate the reliability of this scale, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was computed for all the instrument’s items. The results in Table 3 indicate that HHI was highly reliable, with a Rasch item reliability of 0.886. Notably, all items have a Cronbach’s alpha value lower than the global alpha. The validity of each item on the scale may be confirmed by its correlation with the overall scale. Corrected item–total correlation varied from 0.550 (Item 9) to 0.731 (Item 12).

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics, corrected item–total correlation and Cronbach’s alpha of HHI.

3.2.4. Fit Statistics to the Rasch Model

Table 4 presents the item fit data for all nine items. All Infit MNSQ statistics (t standardized information-weighted mean square statistic) and Outfit MNSQ (standardized outlier-sensitive mean square statistic) were within the recommended range of 0.60–1.40 (Linacre, 2018), with Infit MNSQ ranging from 0.858 to 1.228 logits and Outfit MNSQ ranging from 0.66 to 1.200. The analyzed items demonstrated a satisfactory alignment with the Rasch model, as the weighted mean square statistic fell within the 0.6–1.4 range (Infit > 0.6 and Outfit < 1.4).

Table 4.

Fit statistics for the HHI.

3.2.5. Wright Maps

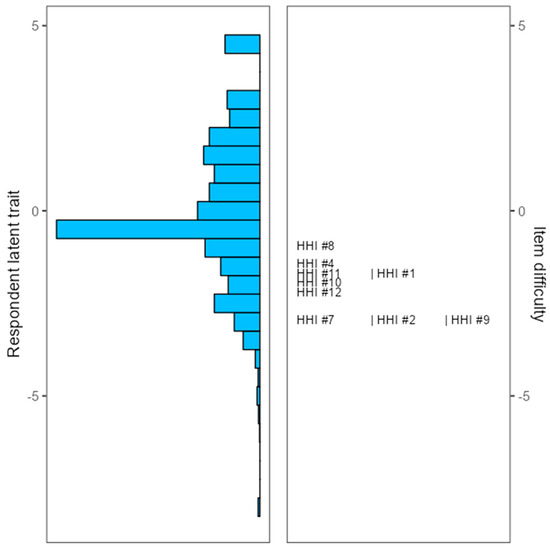

To further understand the power of Rasch analysis for instrument development and improvement, we used a Wright map. A Wright map is a visual representation of the continuum being measured and analyzes the ability of the respondents (left side) and the difficulty of the items (right side). Both ability and difficulty levels are higher at the top and lower at the bottom (Bond & Fox, 2015). Figure 1 displays the item–person map for the HHI’s 9-item version. There is a good distribution of respondent ability, with values ranging from −5 (approximately) to 5 logits (Supplementary Figure S1). Higher scores on the latent dimension indicate items testing higher levels of ability. Regarding item difficulty, there is a similar behavior between the items, especially Items 2, 7 and 9; Item 8 has a particular degree of difficulty, and the rest have a similar degree of difficulty. According to the model, we can estimate the participants’ ability levels with 85% accuracy (internal consistency reliability coefficient = 0.856).

Figure 1.

Person–item map for the HHI.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to assess the psychometric properties of the HHI as a measure of hope in Portuguese Higher Education students using Rasch modeling, with a sample of 2227 students recruited during the COVID-19 outbreak. Structurally speaking, the results indicate a unidimensional solution for the HHI with nine items. Other studies have demonstrated inconsistency in the number of factors. Some studies report a one-factor solution (Geiser et al., 2015; Rustøen et al., 2018; Soleimani et al., 2019; A. Viana et al., 2010), others report a two-factor solution (Haugan et al., 2013; Hunsaker et al., 2016; Van Gestel-Timmermans et al., 2010; Yaghoobzadeh et al., 2019), while some maintain the original solution of three factors (Hirano et al., 2007; R. Marques et al., 2016), namely temporality and future, positive readiness, and expectancy and interconnectedness.

Modifying a questionnaire to suit a different culture can change the interpretation of the questions and the relationships between them, as a result of translation and cultural disparities (Yaghoobzadeh et al., 2019). This is presumably why earlier translations into other languages resulted in significantly different factor solutions. The variation in cultural backgrounds leads to differences in the perception and appraisal of the idea of hope, as stated by Nayeri et al. (2020). This can create opportunities for future investigations to develop a novel, culture-specific tool for assessing hope. Furthermore, the two items framed in a negative manner (#3 and #6) were not effective in measuring the construct. Prior research indicates that the use of reverse-coded items, especially those with negative wording, can result in structural problems similar to those seen in this study (Rustøen et al., 2018). While reverse-keyed items could be useful to control response bias, they do not fulfil this purpose for the HHI.

Hope is better conceptualized as a unidimensional construct, representing a general hope construct that was found to be statistically valid through Rasch analysis. This discrepancy between theory and empiricism in concepts relevant to health had already been described by Rustøen et al. (2018) in their study when validating the HHI using Rasch analysis. These authors point out that although their study also suggested a unidimensional scale, this issue of measuring the concept of hope was not fully resolved, which we also corroborate. Consequently, the present research provides support for other validation methods employed in further research. Moreover, the lingering underlying question is whether hope in non-clinical contexts can be considered as state or trait oriented (i.e., trait hope refers to a relatively stable disposition or personality characteristic, while state hope is a more transient emotional experience influenced by specific situations and contexts). The present study was not designed to answer this question, but considering the results, we might ponder that hope is ‘state-orientated’, understood as the temporary fluctuation in an individual’s sense of hope in response to specific events, short-term circumstances or emotional changes.

Regarding the items that compose the HHI, in a first DIF analysis of the 12 items, 3 items showed a significant DIF (p < 0.001) in relation to sex. These items were removed (#3, #5 and #6), and the remaining nine items demonstrated a good fit for the different groups studied (sex and age). In similar studies on the validation of the HHI, these items were also removed. Item #3 (I feel all alone) was removed in two studies (R. Marques et al., 2016; Rustøen et al., 2018); Item #5 (I have faith that gives me comfort) was removed in the Rustøen study (2018); and Item #6 (I feel scared about my future) was eliminated in three studies (Haugan et al., 2013; R. Marques et al., 2016; Rustøen et al., 2018). Items 3 and 6 are inversely related and can lead to issues due to the potential for measurement mistakes caused by the self-reported measurement method. On the other hand, measurement errors might occur when comparable words and expressions are used in both positive and negative assertions (Yaghoobzadeh et al., 2019). Furthermore, Item #5 did not satisfy the requirements for an acceptable fit with the unidimensional construct. This suggests that there were greater discrepancies in the scores obtained from this item than were anticipated by the Rasch model. A recent Portuguese survey estimated that 58% of young Portuguese belong to a religion or have some beliefs, 50% of whom declare themselves Catholic (Sagnier & Morell, 2021). With the increase in secularization in Europe, transformations have occurred in Portuguese society in recent decades. Compared with Catholic Europe in general, Portugal presents higher values of secularization/religiosity (Coutinho, 2023). In this sense, Lambert (2004) argues that “believing without belonging” remains relevant in situations where the soft variables (belief) continue to hold significance, particularly among young people, while the hard variables (religious practice) decline. This substantial variation in religious affiliation across nations presents a challenge, but it can also be a challenge within a single nation. Typically, faith is also described as a component of hope (Dufault & Martocchio, 1985; Herth, 1992). Higher scores on Item #5 indicate the absence of a significant correlation between the presence of a comforting faith and higher scores on the remaining HHI items; individuals may lack comforting faith but still possess hope, and vice versa. This issue of religion and faith should be further researched to find a link with the hope construct.

Overall, given the present empirical evidence that supports and validates the one-factor model with nine items, we recommend an in-depth and updated theoretical approach through the construct of hope in a non-clinical setting. The theoretical construct, which supports the development of HHI, was developed based on a clinical context with cancer patients some 40 years ago, clearly different from our study with higher education students. Furthermore, in line with past research on higher education students during the COVID-19 pandemic (Lourenço et al., 2022; Lourenço et al., 2021; Schwander-Maire et al., 2022; Tran et al., 2024), hope was positively related to mental health. Even before the pandemic, some studies showed a relationship between hope and academic success (Gallagher et al., 2017; S. C. Marques et al., 2017). It is, therefore, necessary to have instruments that have been properly tested and validated for evaluating hope in academic contexts.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

Utilizing Rasch analysis, a contemporary test theory approach, to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Portuguese variant of the HHI is this study’s greatest asset. The utilization of shorter versions that possess robust psychometric properties is advantageous when conducting large population-based studies. Likewise, this research provides an updated description of higher education students’ responses to a nine-item variant of the HHI using a sizable sample. However, there were several limitations in this study. First, non-probability sampling hinders the capacity to extrapolate the findings and may have influenced findings related to faith and gender variables. For instance, the sample’s overwhelming skew toward female respondents (nearly 80%) could mislead perceptions of item neutrality, particularly regarding affective measures like Item #6, “I feel scared about my future”, or Item #3, “I feel alone.” Further research is necessary involving a more heterogeneous sample and an equitable distribution of participants throughout the nation. It is also advisable to conduct further tests to assess the discriminant and convergent validity of the Portuguese version of the HHI. Second, the gathered data were derived from self-evaluation; hence, there might be a risk for response bias (e.g., social desirability). Self-assessment has faced criticism due to its tendency to generate hope-related outcomes that overstate the true hope status of the respondents. Notwithstanding, the assessments in this sample may be considered reasonable, given that the participants possessed comparable levels of education and were, thus, well-informed regarding matters pertaining to hope. Third, when assessing the difficulty of items in future evaluations of the HHI, it will be crucial to consider variables associated with the participants’ backgrounds. In addition, participants with limited education may find it challenging to identify the most complex items (e.g., faith that comforts), as their inadequate understanding of religious matters or reliance on speculation may influence their responses to this particular test item.

4.2. Implications for Practice

There is a need for further research into hope in non-clinical populations and at different times of crisis and stability. The following research ought to incorporate contemporary test theoretical frameworks, such as the Rasch methodology, to supplement conventional approaches, reassess, and enhance assessment. These reexaminations have the potential to benefit all measurement instrument users. A greater understanding of health-promoting factors, such as hope, is crucial for preventing and enhancing the mental health of higher education students. Hope functions independently of adversities, equipping an individual to confront problems via self-belief and the formulation of solutions to achieve their goals. Hope predicts adaptive coping strategies such as positive reframing, wherein an individual cultivates an optimistic perspective when confronted with bad circumstances (Embalsado, 2024). The findings suggest strategies for creating hope-based interventions that foster self-worth and positive development, eventually resulting in more fulfilling and purposeful lives for higher education students. Moreover, bolstering one’s mental health may contribute to the development of resilience during adulthood and strengthening student motivation for engaging in career planning (Niles et al., 2025). Further research is warranted to examine the various factors that may either strengthen or influence the hope of students in higher education. This knowledge holds significance for stakeholders at both the national and local levels, as it can guide the execution of strategies and interventions that promote health.

5. Conclusions

While there are a few potential limitations, our findings indicate that the Portuguese version of the HHI can serve as a feasible and reliable instrument for evaluating the degree of hope in the general population of Portugal. The HHI showed strong one-dimensionality, and the goodness-of-fit values were satisfactory for all the items. The impact of cross-cultural adaptations on questionnaire interpretation due to translation and cultural disparities was highlighted, emphasizing the necessity for culture-specific tools to accurately assess hope, particularly noting the ineffectiveness of negatively framed items, echoing concerns from previous research.

This study contributes to conceptualizing hope as a unidimensional construct validated through Rasch analysis while acknowledging the ongoing debate on whether hope in non-clinical contexts is state or trait oriented. Additionally, differential item functioning analysis identified three items significantly influenced by gender, prompting their removal, and emphasizes the need to further explore the relationship between religion, faith, and hope, suggesting a refinement of the HHI’s theoretical framework to suit non-clinical contexts better. Finally, this study underscores the importance of validated instruments for assessing hope in academic contexts, given the observed positive correlation between hope, mental health, and academic success among higher education students.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/educsci15091087/s1, Figure S1: Expected scores curve of each item.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L., A.Q. and M.A.D.; methodology, C.L.; software, C.L. and M.A.D.; validation, C.L. and M.A.D.; formal analysis, C.L. and M.A.D.; investigation, C.L. and M.A.D.; resources, C.L. and M.A.D.; data curation, C.L. and M.A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L., A.Q., T.L., Z.C. and M.A.D.; writing—review and editing, C.L., A.Q., T.L., Z.C., A.M.A., F.F.-R., M.Y. and M.A.D.; visualization, C.L., A.M.A., F.F.-R. and M.Y.; supervision, C.L.; project administration, C.L.; funding acquisition, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is also supported by national funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P. [(UID/05704/2023)]—and under the Scientific Employment Stimulus-Institutional Call [(https://doi.org/10.54499/CEECINST/00051/2018/CP1566/CT0012, accessed on 20 July 2025)].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidade Católica Portuguesa (code:74 approved on 15 May of 2020)—and the Ethics Committee of the Polytechnic University of Leiria (CE/IPLEIRIA/22/2020 approved on 1st May of 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their profound gratitude to the students who generously contributed to the study and to the staff who participated in the recruitment process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HHI | Herth Hope Index |

| MNSQ | Mean Square Residuals |

References

- Bond, T. G., & Fox, C. M. (2015). Applying the Rash model: Fundamental measurement in the human sciences (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, T. G., Yan, Z., & Heene, M. (2020). Applying the Rasch model (Fundamental measurement in the human science). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Boone, W. J. (2016). Rasch analysis for instrument development: Why, when, and how? CBE—Life Sciences Education, 15(4), rm4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K. S., Li, H. C. W., Chan, S. W., & Lopez, V. (2012). Herth hope index: Psychometric testing of the Chinese version. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(9), 2079–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, J. P. (2023). Portuguese youth religiosity in comparative perspective. Religions, 14(2), 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufault, K., & Martocchio, B. C. (1985). Symposium on compassionate care and the dying experience. Hope: Its spheres and dimensions. Nursing Clinics of North America, 20, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embalsado, J. V. (2024). Locus-of-Hope intervention in school: A localized strength-based mental health promotion program. International Journal of Public Health, 69, 1607010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farran, C. J., Herth, K. A., & Popovich, J. M. (1995). Hope and hopelessness: Critical clinical constructs. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, M. W., Marques, S. C., & Lopez, S. J. (2017). Hope and the academic trajectory of college students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18(2), 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasper, K., Spencer, L. A., & Middlewood, B. L. (2020). Differentiating hope from optimism by examining self-reported appraisals and linguistic content. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(2), 220–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiser, F., Zajackowski, K., Conrad, R., Imbierowicz, K., Wegener, I., Herth, K. A., & Urbach, A. S. (2015). The German version of the Herth Hope Index (HHI-D): Development and psychometric properties. Oncol Res Treat, 38(7–8), 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, William, C., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengage Learning EMEA. [Google Scholar]

- Haugan, G., Utvaer, B. K., & Moksnes, U. K. (2013). The Herth Hope Index—A psychometric study among cognitively intact nursing home patients. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 21(3), 378–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herth, K. (1992). Abbreviated instrument to measure hope: Development and psychometric evaluation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 17, 1251–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, Y., Sakita, M., Yamazaki, Y., Kawai, K., & Sato, M. (2007). The Herth Hope Index (HHI) and related factors in the Japanese general urban population. Japanese Journal of Health and Human Ecology, 73, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsaker, A. E., Terhorst, L., Gentry, A., & Lingler, J. H. (2016). Measuring hope among families impacted by cognitive impairment. Dementia, 15(4), 596–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley, K., Clark, B., Brown, V., & Sitzia, J. (2003). Good practice in the conduct and reporting of survey research. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 15, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lama, S., & Ahad, T. (2023). Mental health issues among medical students: Exploring predictors of mental health in Dhaka during COVID-19 pandemic. medRxiv, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, Y. (2004). A turning point in religious evolution in Europe. Journal of Contemporary Religion, 19, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjeira, C., Dixe, M. A., & Querido, A. (2023). Mental health status and coping among Portuguese higher education students in the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 13(2), 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjeira, C., Dixe, M. A., Valentim, O., Charepe, Z., & Querido, A. (2021a). Mental health and psychological impact during COVID-19 pandemic: An online survey of Portuguese higher education students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjeira, C., & Querido, A. (2022). Hope and optimism as an opportunity to improve the “Positive Mental Health” demand. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 827320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjeira, C., Querido, A., Marques, G., Silva, M., Simões, D., Gonçalves, L., & Figueiredo, R. (2021b). COVID-19 pandemic and its psychological impact among healthy Portuguese and Spanish nursing students. Health Psychology Research, 9(1), 24508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, D. J., Whelton, W. J., Rogers, T., McElheran, J., Herth, K., Tremblay, J., Green, J., Dushinski, K., Schalk, K., Chamodraka, M., & Domene, J. (2020). Multidimensional hope in counseling and psychotherapy scale. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 30(3), 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linacre, J. M. (2002). Optimizing rating scale category effectiveness. Journal of Applied Measurement, 3, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Linacre, J. M. (2006). Data variance explained by Rasch measure. Rasch Measurement Transactions, 20, 1045. [Google Scholar]

- Linacre, J. M. (2013). Differential item functioning DIF sample size nomogram. Rasch Measurement Transactions, 26, 1391. [Google Scholar]

- Linacre, J. M. (2018). Help for winsteps rasch measurement and rasch analysis software. Available online: https://www.winsteps.com/winman/misfitdiagnosis.htm (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Lourenço, T. M. G., Charepe, Z. B., Pestana, C. B. d. C. F., Rabiais, I. C. M., Alvarez, E. J. S., Figueiredo, R. M. S. A., & Fernandes, S. J. D. (2021). Esperança e bem-estar psicológico durante a crise sanitária pela COVID-19: Estudo com estudantes de enfermagem. Escola Anna Nery, 25, e20200548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, T. M. G., Reis, A., Sáez-Alvarez, E. J., Abreu-Figueiredo, R., Charepe, Z. B., Marques, G., & Gonçalves, M. L. (2022). Predictive model of the psychological well-being of nursing students during the COVID-19 lockdown. SAGE Open Nursing, 8, 23779608221094547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, R., Dixe, M. A., Querido, A., & Sousa, P. P. (2016). Herth hope index for caregivers of persons in palliative care-Portuguese version. CuidArte Enferm, 10(2), 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, S. C., Gallagher, M. W., & Lopez, S. J. (2017). Hope-and academic-related outcomes: A meta-analysis. School Mental Health, 9(3), 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, L., Gupta, T., & Shree, A. (2020). Online teaching-learning in higher education during lockdown period of COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 1, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L. B., Terwee, C. B., Patrick, D. L., Alonso, J., Stratford, P. W., Knol, D. L., Bouter, L. M., & de Vet, H. C. (2010). The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: An international Delphi study. Quality of Life Research, 19(4), 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayeri, N. D., Goudarzian, A. H., Herth, K., Naghavi, N., Nia, H. S., Yaghoobzadeh, A., Sharif, S. P., & Allen, K. A. (2020). Construct validity of the Herth Hope Index: A systematic review. International Journal of Health Sciences, 14(5), 50–57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Neu, T., Rode, J., & Hammer, S. (2024). An examination of social support and mental health in nursing students during COVID-19. Nursing Education Perspectives, 45(2), 112–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niles, J. K., Niles, S. G., & Tsai, Y.-Y. M. (2025). Hope-based interventions to address student well-being and career development. Professional School Counseling, 29(1a), 2156759X251335530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooripour, R., Hosseinian, S., Hussain, A. J., Annabestani, M., Maadal, A., Radwin, L. E., Hassani-Abharian, P., Pirkashani, N. G., & Khoshkonesh, A. (2021). How resiliency and hope can predict stress of COVID-19 by mediating role of spiritual well-being based on machine learning. Journal of Religion and Health, 60(4), 2306–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redlich-Amirav, D., Ansell, L. J., Harrison, M., Norrena, K. L., & Armijo-Olivo, S. (2018). Psychometric properties of Hope Scales: A systematic review. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 72(7), e13213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robles-Bello, M. A., & Sánchez-Teruel, D. (2023). Measurement invariance in gender and age of the Herth Hope Index to the general Spanish population across the lifespan. Current Psychology, 42, 25904–25916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rustøen, T., Lerdal, A., Gay, C., & Kottorp, A. (2018). Rasch analysis of the Herth Hope Index in cancer patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 16(1), 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagnier, L., & Morell, A. (2021). Os jovens em Portugal, hoje. Quem são, que hábitos têm, o que pensam e o que sentem. Fundação Francisco Manuel dos Santos. Available online: https://www.ffms.pt/sites/default/files/2022-07/os-jovens-em-portugal-hoje.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Sartore, A. C., Alves, S. A., & Herth, K. A. (2010). Cultural adaptation and validation of the Herth Hope Index for Portuguese language: Study in patients with chronic illness. Texto & Contexto—Enfermagem, 19(4), 754–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Teruel, D., Robles-Bello, M. A., & Camacho-Conde, J. A. (2020). Adaptation and psychometric properties in Spanish of the Herth Hope Index in people who have attempted suicide. Psychiatric Quartely, 92(1), 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwander-Maire, F., Querido, A., Cara-Nova, T., Dixe, M. A., Aissaoui, D., Charepe, Z., Christie, D., & Laranjeira, C. (2022). Psychological responses and strategies towards the COVID-19 pandemic among higher education students in Portugal and Switzerland: A mixed-methods study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 903946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seol, H. (2023). snowIRT: Item response theory for Jamovi (Version 4.8.8) [jamovi module]. Available online: https://github.com/hyunsooseol/snowIRT (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Soldato, G., Lima, A., Bizotto, T., Brienze, V., André, J., & Caldas, H. (2023). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of academics in the health area. Concilium, 23(14), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, M., Allen, K., Herth, K., & Sharif, S. (2019). The Herth Hope Index: A validation study within a sample of Iranian patients with heart disease. Social Health and Behavior, 2, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayhorn, T. (2023). Hope and mental health: An investigation of loneliness, depression, stress, and hope in university students amid COVID-19. Journal of Psychology & Behavior Research, 5(1), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streiner, D. L., & Kottner, J. (2014). Recommendations for reporting the results of studies of instrument and scale development and testing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(9), 1970–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streiner, D. L., & Norman, G. (2008). Health measurement scales: A practical guide to the development and use (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y., Yu, H., Wu, X., & Ma, C. (2023). Sense of hope affects secondary school students’ mental health: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1097894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tennant, A., & Conaghan, P. G. (2007). The Rasch measurement model in rheumatology: What is it and why use it? When should it be applied, and what should one look for in a Rasch paper? Arthritis Care Research, 57, 1358–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, M. A. Q., Khoury, B., Chau, N. N. T., Van Pham, M., Dang, A. T. N., Ngo, T. V., Ngo, T. T., Truong, T. M., & Le Dao, A. K. (2024). The role of self-compassion on psychological well-being and life satisfaction of Vietnamese undergraduate students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Hope as a Mediator. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 42(1), 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gestel-Timmermans, H., Van Den Bogaard, J., Brouwers, E., Herth, K., & Van Nieuwenhuizen, C. (2010). Hope as a determinant of mental health recovery: A psychometric evaluation of the Herth Hope Index-Dutch version. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 24(1), 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velez, M. J., Marujo, H. A., Charepe, Z., Querido, A., & Laranjeira, C. (2024). Well-being and dispositional hope in a sample of Portuguese citizens: The mediating role of mental health. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 14(7), 2101–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, A., Querido, A., Dixe, M. A., & Barbosa, A. (2010). Avaliação da esperança em cuidados paliativos: Tradução e adaptação transcultural do Herth Hope Index. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 2(1), 607–616. Available online: https://iconline.ipleiria.pt/entities/publication/bf009353-4a13-475e-b1c6-616a1fbf9221 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Viana, J., Gonçalves, S. P., Brandão, C., Veloso, A., & Santos, J. V. (2023). The challenges faced by higher education students and their expectations during COVID-19 in Portugal. Education Sciences, 13, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R., Zhang, C., Lai, Q., Hou, Y., & Zhang, X. (2021). Applicability of the dual-factor model of mental health in the mental health screening of Chinese college students. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 549036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaghoobzadeh, A., Pahlevan Sharif, S., Ong, F. S., Soundy, A., Sharif Nia, H., Moradi Bagloee, M., Sarabi, M., Goudarzian, A. H., & Morshedi, H. (2019). Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation of the Herth Hope Index within a sample of iranian older peoples. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 89(4), 356–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yotsidi, V., Nikolatou, E.-K., Kourkoutas, E., & Kougioumtzis, G. A. (2023). Mental distress and well-being of university students amid COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from an online integrative intervention for psychology trainees. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1171225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).