Abstract

The Cultural STEM Night (CSN) initiative was developed to address the persistent lack of culturally relevant STEM teaching materials, which often contributes to student disengagement—particularly among underrepresented populations. This study examined the impact of the CSN program on enhancing STEM affinity and cultural intelligence (CQ) among American and Korean teacher candidates. Over six weeks, participants engaged in synchronous workshops, virtual cultural exchanges, and collaborative STEM lesson design integrating Korean cultural contexts. Quantitative analysis of pre- and post-program surveys using the STEM Affinity Test and Cultural Intelligence Scale revealed statistically significant improvements across all subdomains of STEM affinity (identity, interest, self-concept, value, and attitudes) and in most dimensions of CQ (metacognitive, cognitive, and behavioral). However, motivational CQ did not show significant gains, likely due to limited student interaction time during the event. Qualitative data from written reflections and focus group discussions supported these findings, indicating increased instructional adaptability, cultural awareness, and confidence in designing inclusive STEM lessons. These results demonstrate the transformative potential of interdisciplinary, culturally immersive programs in teacher education. The CSN model, supported by digital collaboration tools, offers a scalable and effective approach to preparing educators for diverse classrooms. Findings underscore the importance of integrating culturally responsive teaching into STEM education to promote equity, engagement, and global competence.

1. Introduction

STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) education is critical for equipping students to navigate complex global challenges. However, classrooms in the United States with high minority populations often lack culturally relevant instructional materials, contributing to disengagement and lower academic outcomes in STEM disciplines (Thevenot, 2021). When students do not see their identities and lived experiences reflected in the curriculum, their motivation and achievement in STEM tend to decline (Ladson-Billings, 1995). Culturally relevant pedagogy (CRP) offers a powerful solution by integrating students’ cultural contexts into instruction, thereby promoting deeper engagement and improved academic performance (Gay, 2010).

Despite growing support for CRP, its application in STEM education remains limited, particularly in international teacher preparation programs (Milner, 2022; Howard, 2010). Addressing this gap, the present study’s main objective is to evaluate how a cross-national, culturally responsive STEM initiative can simultaneously strengthen teacher candidates’ STEM affinity and cultural intelligence.

To achieve this overarching aim, the study pursues three sub-objectives:

- To examine whether participation in the Cultural STEM Night (CSN) program enhances teacher candidates’ confidence and identification with STEM disciplines.

- To assess the program’s effectiveness in developing participants’ intercultural competence and cultural awareness.

- To explore how technology-mediated, cross-national collaboration influences the design and delivery of culturally responsive STEM lessons.

These objectives are directly aligned with the study’s research questions, which investigate whether the CSN program effectively (1) enhances STEM affinity and (2) increases cultural intelligence among teacher candidates in the United States and South Korea.

The following literature review examines five strands of scholarship relevant to the present study: (1) equity in STEM education, (2) culturally responsive teaching in STEM, (3) teacher preparation for CRT, (4) cross-national collaborations in teacher education, and (5) Technology as an Enabler of Culturally Responsive STEM Instruction.

1.1. Equity in STEM Education

STEM education is fundamental in preparing students to thrive in a knowledge-based, innovation-driven economy. Ensuring equitable access to high-quality STEM instruction for students from diverse backgrounds is essential not only for individual achievement but also for cultivating a workforce capable of addressing 21st-century global challenges (National Academies of STEMs, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018).

Despite this imperative, disparities in STEM access persist, particularly among students from underrepresented and marginalized communities. Schools in low-income areas often lack critical resources such as up-to-date laboratory facilities, advanced coursework, and extracurricular STEM opportunities (National Center for Education Statistics, 2022). These deficiencies can impede student engagement and academic development, reinforcing cycles of educational inequity. Additionally, implicit bias among educators may result in reduced expectations and fewer opportunities for minority students, further discouraging participation in STEM fields (Gutstein et al., 2013). Such systemic inequities contribute to the persistent underrepresentation of minority students in STEM (Eaton et al., 2020).

1.2. Culturally Responsive Teaching (CRT) in STEM

Culturally responsive teaching (CRT) is an instructional approach that values students’ cultural identities and learning preferences, promoting an inclusive and effective learning environment in STEM education (Gay, 2010). Grounded in social constructivist theory, CRT emphasizes the influence of cultural context and interpersonal interaction on learning (Vygotsky, 1978). Empirical evidence demonstrates that CRT can increase academic engagement and performance by affirming students’ identities and connecting academic content to their lived experiences (Gay, 2018; Hammond, 2015).

CRT also fosters intercultural competence and prepares students for participation in a global society (Rubin, 2017; Deardorff, 2009). For example, educators can incorporate culturally relevant examples—such as energy sources familiar to students’ communities—or invite speakers from diverse backgrounds to broaden students’ perspectives and aspirations. Furthermore, CRT embraces multiple instructional strategies to accommodate varied learning styles, including collaborative projects, simulations, and visual aids (Howard, 2010), thereby ensuring equitable access to STEM concepts for all learners.

1.3. Teacher Preparation for Culturally Responsive Teaching

Preparing educators to implement CRT is essential for fostering equity in STEM education. Professional development programs that address cultural awareness, instructional adaptation, and implicit bias can significantly improve teachers’ confidence and competence in working with diverse student populations (Darling-Hammond et al., 2002; Howard, 2010). Evidence shows that middle school STEM teachers who received CRT-focused training demonstrated improved integration of cultural contexts in their instruction and reported positive impacts on student learning outcomes (Milner, 2022). Successful professional development models often include coaching, collaborative learning communities, and sustained support systems, which promote reflective practice and instructional growth.

Additionally, CRT training helps teachers establish meaningful relationships with students by bridging home and school cultures and addressing the social-emotional dimensions of learning (Villegas & Lucas, 2002). These relationships foster a greater sense of belonging and contribute to students’ academic success.

1.4. Cross-National Collaboration in Teacher Education

Collaborative programs involving American and Korean teacher candidates have proven effective in enhancing culturally responsive teaching practices in STEM education (Yoon et al., 2022; Yoon & Martin, 2019). Such cross-cultural partnerships not only increase cultural competence but also elevate teacher candidates’ interest in STEM and awareness of diverse educational practices.

Joint lesson planning, virtual classroom exchanges, and intercultural discussions offer teacher candidates rich opportunities to explore culturally relevant teaching strategies. These experiences deepen understanding of how culture shapes learning and empower participants to create inclusive STEM lessons.

Key components of effective cross-cultural programs include:

- Interactive and collaborative learning—promoting intercultural dialogue and mutual understanding;

- Culturally relevant pedagogy—equipping teacher candidates with tools to integrate students’ cultural backgrounds into STEM instruction;

- Continuous reflection and feedback—encouraging professional growth through structured dialogue;

- Use of technology—facilitating real-time collaboration despite geographic distance;

- Mentorship opportunities—providing experienced guidance in culturally responsive teaching.

Participants in such programs consistently report improved cultural awareness, instructional adaptability, and preparedness for diverse classrooms, all of which are vital for equitable and engaging STEM instruction.

1.5. Technology as an Enabler of Culturally Responsive STEM Instruction

Technology plays a pivotal role in enabling international collaboration among teacher candidates. While video conferencing tools such as Zoom were used for real-time interaction and shared instructional planning across time zones (Enkhtur et al., 2024), the program also integrated a range of specialized educational technologies to enhance engagement, co-creation, and instructional planning. For example, collaborative design platforms such as Jamboard, Miro, and Canva supported visual brainstorming and lesson-material development (Singh et al., 2023), while PhET Interactive Simulations (Perkins et al., 2006) and Tinkercad (Autodesk, 2020) were introduced as hands-on resources for STEM concept exploration. Participants also used Google Earth to integrate geographic and cultural context into science lessons, linking content to real-world locations relevant to students’ backgrounds (Fatayan, 2024).

During training sessions, targeted workshops were conducted to familiarize teacher candidates with these tools, emphasizing not only technical functionality but also culturally responsive application. For instance, one session demonstrated how to adapt PhET simulations for bilingual instruction, while another explored ways to use Canva to incorporate culturally relevant visuals into teaching materials (Gay, 2010).

To maximize the effectiveness of online meetings, videoconference sessions were carefully structured: agendas were shared in advance, breakout rooms were assigned for small-group collaboration, and time was allocated for reflection and peer feedback (Bond et al., 2021). Moderators used strategies such as rotating facilitation roles among participants to encourage equitable participation, and embedded polls or live quizzes via Mentimeter and Kahoot! to sustain engagement (Wang & Tahir, 2020).

Asynchronous collaboration spaces in Google Classroom and shared cloud drives enabled participants to continue refining materials between meetings, making the exchange more flexible and inclusive (Enkhtur et al., 2024). While challenges such as internet connectivity issues, varied digital skill levels, and language differences were encountered, these were addressed through pre-session technical orientations, multilingual instructional guides, and the pairing of participants into cross-national support teams (Örtegren, 2022).

Through this blended approach of synchronous, asynchronous, and specialized tool use, technology was not merely a communication medium but also became an active enabler of culturally responsive, cross-national STEM instruction.

1.6. Research Questions

Based on these strands of research, this study introduces the “Cultural STEM Night” (CSN) initiative, an online collaboration between American and Korean teacher candidates. The program is designed to enhance participants’ ability to develop culturally inclusive STEM lessons while fostering intercultural competence.

This study evaluates the effectiveness of CSN in promoting two key outcomes: (1) STEM affinity and (2) cultural intelligence among teacher candidates in the United States and South Korea. The findings contribute to the field by demonstrating how culturally responsive, cross-national teacher education can improve both instructional quality and cultural competence.

The research questions guiding this study are:

- (1)

- Does the CSN program effectively enhance STEM affinity among the participants in the United States and South Korea?

- (2)

- Is the CSN program effective in increasing cultural intelligence among the participants in the United States and South Korea?

2. Materials and Methods

This study investigated the impact of collaborative, culturally responsive teaching by pairing American and Korean teacher candidates in an international, semester-long STEM education course. An American STEM methods instructor partnered with a Korean instructor to design and implement a unique teacher preparation model focused on culturally responsive instruction. The project adhered to ethical standards applicable to non-clinical, educational research; no interventions involving human or animal subjects requiring IRB approval were conducted.

2.1. Participants

A total of 30 teacher candidates—18 from the United States and 12 from South Korea—were recruited to participate in this study. Participants were assigned to six cross-national groups, each composed of three American and two Korean candidates. Groups collaborated to develop culturally responsive STEM lessons aligned with Grade 5 Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills (TEKS) standards. Lesson topics included Matter and Energy, Force and Motion, Earth and Space, and Organisms and Environments. Open Educational Resources (OER) related to culturally responsive teaching and Korean history were provided as references. Final lesson plans were collaboratively developed on Padlet and presented to elementary students and parents during a live virtual event—Cultural STEM Night—hosted via Google Meet. The completed lessons were later compiled and published on Pressbook, providing public access for broader educational use.

2.2. Study Design and Procedure

The six-week study was organized into weekly modules that supported cross-cultural engagement, instructional development, and reflective practice:

- Week 1: Researchers collaboratively reviewed existing literature on international online collaboration and culturally responsive pedagogy. These insights informed the design of a week-by-week syllabus and activity schedule.

- Week 2: Participants attended a three-hour synchronous lecture focused on integrating Korean culture into STEM instruction through Zoom (Figure 1). This session established foundational knowledge in cultural awareness and communication practices.

Figure 1. Teacher Candidates’ STEM Affinity pre-and post-intervention.

Figure 1. Teacher Candidates’ STEM Affinity pre-and post-intervention. - Week 3: A three-hour virtual cultural excursion, delivered via Microsoft Teams, allowed participants to explore elements of Korean culture. Teacher candidates were encouraged to continue informal cross-cultural dialogue outside class.

- Week 4: Group members spent approximately eight hours collaborating synchronously and asynchronously to co-design culturally responsive STEM lesson plans. Lesson drafts were shared on Padlet, and each group presented their work during Cultural STEM Night.

- Week 5: Reflection activities were conducted via online discussion forums. Participants shared insights, challenges, and suggestions for improvement, and were regrouped to encourage active listening and respectful cross-cultural dialogue.

- Week 6: Researchers synthesized reflections and evaluations to revise the course syllabus and publish the culturally responsive teaching curriculum on Pressbook, supporting continuous improvement and scalability.

To accommodate language differences and promote equitable cross-cultural collaboration, the course incorporated both synchronous and asynchronous learning modalities, with staggered meeting times to account for time zone differences. Participants were paired in a 3-to-2 ratio—three American and two Korean teacher candidates per group—to foster meaningful collaboration and ensure individualized engagement across cultural and linguistic backgrounds. This structure enabled all participants to contribute effectively while developing culturally responsive STEM instruction. A detailed six-week program schedule, emphasizing the integration of Korean culture into STEM education through international online collaboration, is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Schedule for the Study Activities.

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

To evaluate the effectiveness of the Cultural STEM Night (CSN) initiative, a mixed-methods research design was employed, combining both quantitative and qualitative data sources to provide a comprehensive understanding of the participants’ development in STEM affinity, cultural intelligence, and instructional practices. This approach aligns with the definition of mixed-methods research as “an intellectual and practical synthesis” of qualitative and quantitative approaches to gain deeper insights than either method alone (Johnson et al., 2007). The combination of survey instruments and open-ended reflections allowed for triangulation of data, enhancing the validity and richness of the findings (Onwuegbuzie & Collins, 2007).

Additionally, the study utilized pre- and post-program assessments, a design rooted in experimental and quasi-experimental methodology (Campbell & Stanley, 1963), to measure changes over time. This structure supports causal inferences about the impact of the CSN program by comparing participants’ responses before and after the intervention.

2.3.1. Quantitative Instruments

Two validated survey instruments were administered before and after the six-week program: the STEM Affinity Test and the Cultural Intelligence Scale (CQS).

The STEM Affinity Test, developed by Fouad and Santana (2017), is grounded in Social Cognitive Career Theory (SCCT) and was designed to assess students’ psychological engagement with STEM disciplines. It consists of 28 items rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree) and measures five key constructs: STEM identity, self-concept, value, personal interest, and attitudes. The instrument has demonstrated high internal reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients exceeding 0.80 across subscales. Its theoretical foundation emphasizes the role of self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and personal goals in shaping STEM-related choices and persistence, particularly among underrepresented populations.

The Cultural Intelligence Scale (CQS) measured participants’ ability to function effectively in culturally diverse settings. The CQS includes 19 items across four dimensions: cognitive, metacognitive, motivational, and behavioral cultural intelligence. Each dimension has shown strong construct validity and internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values above 0.70 (Van Dyne et al., 2008).

2.3.2. Qualitative Reflections

Qualitative data were gathered through open-ended written reflection prompts and post-program focus group interviews to gain deeper insight into participants’ experiences and perceptions. These methods were chosen to explore how participants engaged with culturally responsive teaching, cross-cultural collaboration, and lesson development—core themes aligned with the study’s research questions.

Participants responded to reflection prompts designed to elicit meaningful narratives that connect directly to the research aims:

- “Describe a moment during the course when your understanding of cultural responsiveness deepened”.This prompt relates to the research question on how participants’ perspectives on culturally responsive teaching evolved through the program. It captures shifts in awareness and pedagogical understanding.

- “How did collaborating with peers from another culture influence your approach to lesson planning?”This question explores the impact of cross-cultural collaboration on instructional design, directly addressing the research question about intercultural engagement and its influence on teaching practices.

- “What challenges did you face in integrating Korean culture into your STEM lessons, and how did you overcome them?”This prompt investigates the practical application of culturally responsive strategies and the problem-solving processes participants employed—key aspects of the study’s inquiry into implementation barriers and adaptations.

At the end of the course, virtual focus group discussions were conducted to further explore participants’ perceptions. These sessions allowed participants to elaborate on their written reflections and engage in dialogue with peers. All discussions were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed thematically to identify recurring patterns and insights related to cross-cultural engagement, instructional practices, and the development of culturally responsive STEM lessons.

2.3.3. Data Analysis Procedures

Quantitative data from the STEM Affinity Test (Fouad & Santana, 2017) and CQS (Ang et al., 2007) were analyzed using statistical software (SPSS 15). Paired sample t-tests were conducted to evaluate pre- and post-program changes in participants’ scores, with a significance threshold set at p < 0.05. This approach aligns with standard practices in quasi-experimental designs for educational research (Campbell & Stanley, 1963), allowing for the assessment of program impact over time.

Qualitative data from written reflections and focus group transcripts were analyzed using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). An inductive coding approach was applied to identify emergent themes, which were then organized into broader categories related to cultural competence, collaborative learning, and pedagogical growth. This method enabled the researchers to capture nuanced participant experiences and align them with the study’s research questions.

The integration of quantitative and qualitative data followed a convergent mixed-methods design (Johnson et al., 2007), allowing for triangulation and a more comprehensive understanding of the CSN program’s impact. This methodological approach enhanced the credibility and depth of the findings and informed recommendations for future culturally responsive STEM teacher preparation models.

2.4. Use of Technology and AI Disclosure

The study relied on digital platforms including Zoom, Microsoft Teams, Google Meet, and Padlet to facilitate real-time communication and collaborative work. All instructional materials and reflections were archived for transparency and instructional use. Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) tools were not used in the development, analysis, or writing of this research. Any AI-assisted editing was limited to grammar and formatting, which does not require disclosure under the journal’s guidelines.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of the CSN Program on STEM Affinity

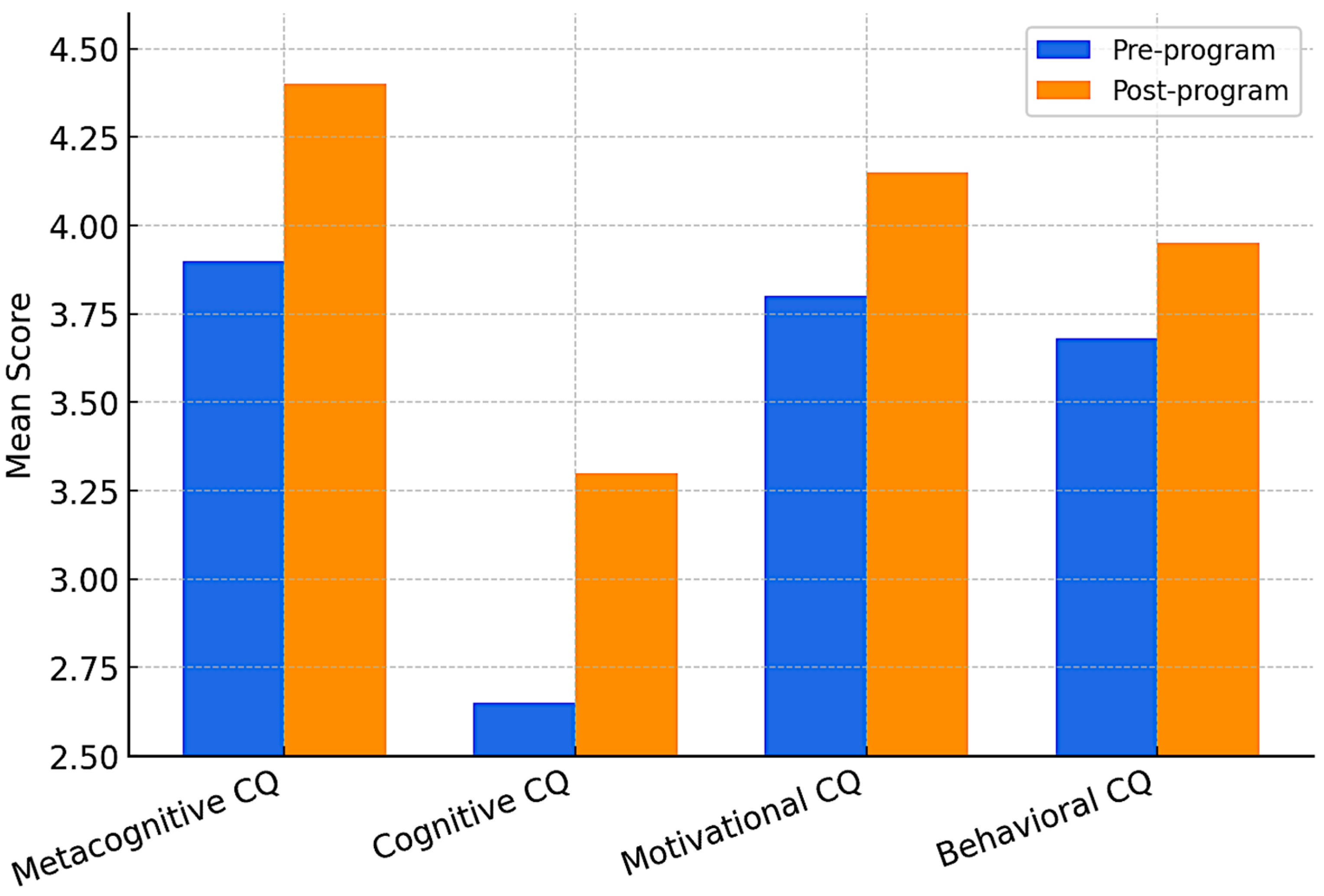

STEM affinity encompasses five key subcomponents: STEM identity, personal interest in STEM, self-concept of ability in STEM, STEM values, and attitudes toward STEM. As shown in Table 2, the implementation of the CSN program resulted in statistically significant improvements across all five dimensions. The most pronounced gain was observed in participants’ attitudes toward STEM, suggesting that the program effectively cultivated more favorable perceptions and a greater appreciation for the subject. This positive shift in attitudes is particularly noteworthy, as it has the potential to enhance teacher candidates’ engagement with STEM content and increase their motivation to teach STEM subjects confidently and enthusiastically in future classrooms.

Table 2.

Results of teacher candidates’ STEM affinity.

Figure 1 visually represents the mean differences in STEM affinity components before and after the intervention, emphasizing the growth in teacher candidates’ STEM identity, self-concept, value, personal interest, and attitudes.

3.1.1. STEM Identity

The analysis of responses related to STEM identity provides important insights into the evolving self-perception of teacher candidates from the United States and South Korea. As illustrated in Table 3, mean scores for all items assessing STEM identity increased following participation in the CSN program, indicating an overall positive shift in self-perception for both groups.

Table 3.

Responses to STEM identity items.

Notably, American teacher candidates reported significantly higher mean scores than their Korean counterparts on items 3 (“I am good at STEM”) and 4 (“I think of myself as a professional in STEM”), suggesting greater confidence in their STEM abilities and professional identity. This disparity in self-perception may reflect broader cultural influences on self-efficacy. Although Korean candidates were high academic performers and STEM majors, many expressed uncertainty regarding their STEM proficiency. Engaging with peers from a different educational system and encountering alternative approaches to problem-solving might have made some participants more aware of areas for growth, leading to more conservative self-ratings. This shift does not necessarily indicate a loss of actual competence, but rather a recalibration of self-perception in light of new experiences and higher perceived benchmarks. These findings are consistent with Kim (2022), who reported that Korean teacher candidates often exhibit lower self-efficacy in inquiry-based teaching despite strong content knowledge. Cultural norms that emphasize modesty or discourage self-assertion may further contribute to this contrast in confidence between U.S. and Korean participants. Together, these factors suggest that the decrease in self-rating may reflect increased self-awareness rather than diminished ability.

3.1.2. Personal Interest in STEM

The evaluation of personal interest in STEM, as detailed in Table 4, provides meaningful insights into the impact of the CSN program on teacher candidates from both the United States and South Korea. Mean scores across all items measuring personal interest increased following the program, indicating enhanced engagement and enthusiasm for STEM. While American participants consistently reported slightly higher scores than their Korean counterparts, both groups demonstrated similar patterns of improvement, suggesting the program was effective across cultural contexts.

Table 4.

Responses to personal interest in STEM items.

The most substantial gain was observed for item 5, which assesses the connection between STEM and everyday life. This improvement may be attributed to the program’s emphasis on designing culturally integrated STEM lessons. By incorporating elements such as art, nature, and architecture from their respective cultural backgrounds, teacher candidates were able to perceive STEM as more relevant and applicable in diverse, real-world settings.

Qualitative reflections reinforced these findings. Participants noted that the program broadened their perspectives on how STEM can intersect with cultural themes. Comments such as, “I am more open to incorporating different cultures into STEM topics”, and “This project made STEM more interesting to me by connecting it to cultural contexts”, underscore the program’s role in fostering deeper, more meaningful interest in STEM education.

3.1.3. Self-Concept of Ability in STEM

As shown in Table 5, the evaluation of self-concept of ability in STEM offers important insights into how American and Korean teacher candidates perceive their competence in STEM disciplines. Consistent with trends observed in STEM identity (Table 3), American candidates reported higher mean scores across all self-concept items, suggesting a stronger self-perception of STEM ability compared to their Korean counterparts. This pattern reflects previous findings from international assessments such as TIMSS and PISA, where Korean students, despite high academic performance, tend to report lower confidence in their STEM abilities (Kwak, 2018).

Table 5.

Responses to the self-concept of ability on STEM items.

Among Korean teacher candidates, participation in the CSN program led to significant gains in self-concept scores, indicating that the program helped address some confidence-related challenges. While a few participants noted limited changes—citing the elementary-level focus of lesson design—others reported increased confidence, particularly in applying scientific knowledge within cultural contexts and communicating it effectively. This variation underscores the individualized impact of the program. As one participant remarked, “It was too short to have substantial changes, but I feel a little more confident about STEM than before”, suggesting that even short-term exposure to culturally relevant STEM instruction can support the development of teacher candidates’ confidence in their STEM teaching capabilities.

3.1.4. Perceptions of STEM Values

The evaluation of responses to STEM values items, presented in Table 6, offers meaningful insights into how American and Korean teacher candidates perceive the importance and relevance of STEM education. Consistent with earlier findings, Korean participants initially reported lower perceptions of STEM value compared to their American counterparts. This aligns with prior research by Kwak (2018), which noted that Korean students ranked 36th to 37th out of 39 countries in the 2015 TIMSS assessment regarding the perceived value of science education.

Table 6.

Responses to STEM values items.

Following participation in the CSN program, both groups exhibited notable improvements in their value perception scores. This suggests that the program effectively enhanced participants’ appreciation of STEM, regardless of cultural background. Open-ended feedback further supported this trend, with teacher candidates emphasizing the meaningfulness and future importance of understanding STEM concepts.

These findings reflect a positive shift in attitudes toward STEM and suggest that the CSN program contributed to fostering a deeper recognition of STEM’s relevance in both education and broader society. This is particularly significant, as valuing STEM is essential for teacher candidates who will be responsible for promoting STEM engagement and literacy in their future classrooms.

3.1.5. Attitudes Toward STEM

The evaluation of responses to attitudes toward STEM items reveals significant positive changes (Barbera et al., 2008) among teacher candidates following their participation in the CSN program (Table 7). Participants showed improved attitudes across all STEM-related items after completing the program, indicating that the CSN effectively enhanced their overall perception of STEM education.

Table 7.

Responses to attitudes toward STEM items.

Although there were slight differences in mean scores between American and Korean teacher candidates, the overall distribution patterns were similar. Both groups exhibited strong interest and positive attitudes toward STEM, demonstrating a shared appreciation for the subject despite cultural differences.

Open-ended feedback from participants further highlighted this shift in attitude. For example, one participant shared, “I hadn’t thought about applying STEM to culture-related topics before, so this project made STEM more interesting to me”. Such reflections emphasize the program’s success in making STEM education more relatable and engaging for teacher candidates. This feedback underscores the CSN program’s role in encouraging teacher candidates to integrate cultural contexts within STEM education. This approach not only fosters greater interest in STEM but also enriches the learning experience by connecting scientific concepts to real-world cultural applications.

3.2. Effects of the CSN Program on Cultural Intelligence (CQ)

The CSN program significantly enhanced teacher candidates’ cultural intelligence (CQ), better preparing them to engage effectively in diverse educational environments. By integrating scientific concepts with cultural contexts, the program helped candidates connect STEM content to traditions, heritage, and the arts from various cultures. This approach enriched their understanding of both STEM education and cultural diversity.

Teacher candidates implemented culturally relevant lessons with elementary students, providing authentic, hands-on teaching experiences that bridged theory and practice. These real-world applications deepened their capacity to deliver STEM instruction in culturally responsive ways.

Additionally, collaborative exchanges with teachers from partner countries offered valuable insights into differing educational systems, classroom norms, lesson planning strategies, and teacher roles. For many Korean teacher candidates, teaching American elementary students for the first time proved to be a transformative experience. Despite initial challenges in unfamiliar classroom settings, they reflected positively on the opportunity, highlighting personal and professional growth. Likewise, American candidates reported increased appreciation for global perspectives and enhanced teaching skills.

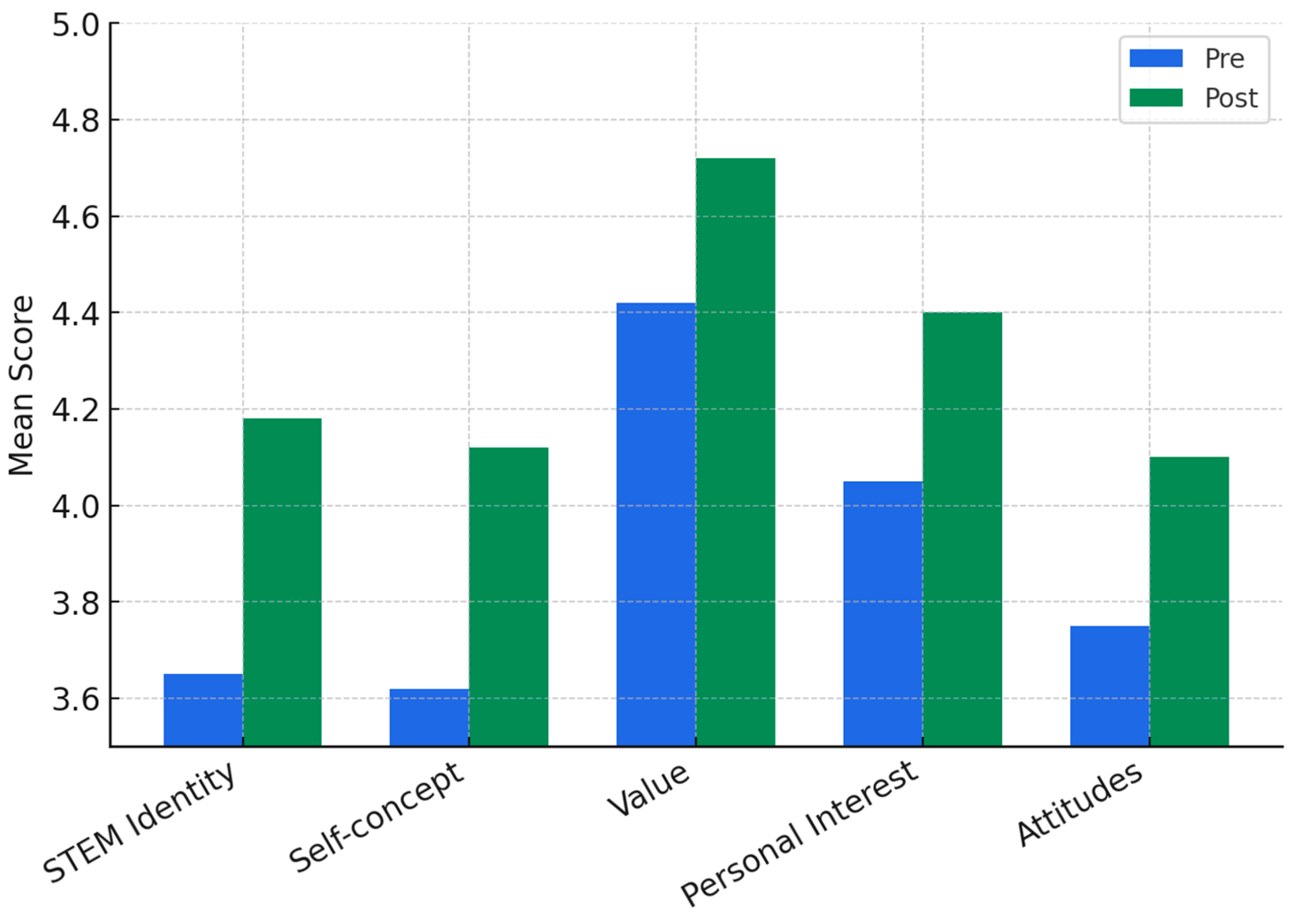

Pre- and post-program assessments using the Cultural Intelligence Scale (CQS) revealed statistically significant improvements across all four CQ domains: cognitive, metacognitive, motivational, and behavioral (Table 8). These findings highlight the CSN program’s effectiveness in fostering teacher candidates’ ability to navigate and succeed in culturally diverse educational contexts.

Table 8.

Results of teacher candidates’ cultural intelligence.

Figure 2 illustrates the pre- and post-program mean scores for teacher candidates’ cultural intelligence across four dimensions.

Figure 2.

Teacher candidates’ cultural intelligence scores.

3.2.1. Metacognitive Cultural Intelligence (CQ)

An analysis of teacher candidates’ responses reveals significant growth in metacognitive cultural intelligence (CQ) as a result of their participation in the CSN program. Metacognitive CQ, as defined by Van Dyne et al. (2008), refers to an individual’s awareness and control of their cultural thinking during intercultural interactions. This form of CQ is essential for fostering active reflection and adaptability in multicultural educational settings.

Throughout the program, teacher candidates showed a marked increase in their curiosity about and appreciation for cultural differences. Many began the program perceiving cultural diversity as unfamiliar or distant. However, through sustained interaction with international peers, they developed a greater understanding of shared human experiences across cultures—an indication of enhanced metacognitive CQ.

Reflective statements from participants illustrate this growth. One candidate remarked, “The event opened my eyes to how important and special it is to incorporate culture into students’ learning. It strengthens their knowledge and awareness of different people and their cultures”. Another shared, “It strengthened my skills by helping me analyze all the different ways culture could be tied in, even if it’s not immediately obvious”. These reflections underscore participants’ deepened ability to critically engage with cultural content in educational contexts—a key indicator of metacognitive CQ.

As shown in Table 9, metacognitive CQ scores improved significantly following the program. Although Korean teacher candidates scored slightly lower than their American counterparts, their gains were substantial. Given their initial limited exposure to English-speaking classroom environments, this progress highlights the CSN program’s effectiveness in fostering cultural awareness and reflective thinking.

Table 9.

Responses to metacognitive CQ items.

Overall, the growth in metacognitive CQ demonstrates that the CSN program successfully equipped teacher candidates with the critical skills needed to incorporate diverse cultural perspectives into their teaching. This development strengthens their capacity to create inclusive, culturally responsive learning environments and underscores the program’s value in preparing educators for today’s multicultural classrooms.

3.2.2. Cognitive Cultural Intelligence (CQ)

Cognitive cultural intelligence (CQ) is defined as “an individual’s awareness and understanding of norms, practices, and conventions in diverse cultural settings” (Van Dyne et al., 2008, p. 17). This dimension of CQ is essential for recognizing cultural similarities and differences, enabling individuals to make informed decisions and engage effectively in multicultural contexts.

The CSN program significantly enhanced teacher candidates’ cognitive CQ by immersing them in various cultural elements of the host nation, including landscapes, traditional games, music, art, and crafts. For Korean teacher candidates, the experience was particularly impactful, as they gained a deeper understanding of how scientific concepts are communicated in American classrooms. They observed linguistic patterns used in classroom questioning and response, as well as strategies that promote interactive and student-centered learning.

One participant shared, “In our presentation, we talked about volcanic landscapes of Jeju Island in South Korea and compared them with similar landscapes in the U.S. In this way, I got to know about some famous national parks in various states”. This reflection illustrates how cross-cultural comparisons broadened candidates’ geographical and cultural knowledge, contributing to the development of cognitive CQ.

Another teacher noted, “By preparing the class, I learned more about my own Korean culture. I also tried to use sentences I learned from videos of American schools. This way, I felt more fluent in a foreign language, and I understood how differences in word choice affect classroom atmosphere”. This statement highlights the dual benefits of the program—enhancing both cultural self-awareness and cross-cultural communication skills.

As shown in Table 10, cognitive CQ scores improved significantly among teacher candidates following the program. Notably, Korean participants reported higher mean scores than their American peers, both before and after the program. This may reflect their prior exposure to American culture, despite having comparatively lower English proficiency. While American candidates expanded their understanding of Korean culture, many still recognized gaps in their knowledge. Korean candidates, on the other hand, demonstrated a stronger grasp of classroom communication (e.g., item 6) but reported limited understanding of U.S. legal, economic, and social systems, including marriage customs.

Table 10.

Responses to cognitive CQ items.

These findings highlight the importance of ongoing cultural exchange and education. Programs like CSN play a vital role in bridging cultural knowledge gaps and equipping future educators with the cognitive tools needed to navigate and thrive in diverse classroom settings. By fostering greater cultural awareness and understanding, such programs contribute to the development of more inclusive and effective teaching practices.

3.2.3. Motivational Cultural Intelligence (CQ)

Motivational cultural intelligence (CQ) is a critical component for educators, as it reflects their capacity to channel attention and energy toward understanding and engaging with cultural differences—thereby enhancing their effectiveness in diverse educational settings (Van Dyne et al., 2008). Closely linked to self-efficacy, this dimension of CQ encompasses the confidence and intrinsic motivation to interact with individuals from various cultural backgrounds.

The CSN program significantly strengthened teacher candidates’ confidence in integrating cultural elements into their STEM instruction. Many participants initially expressed concerns about language barriers and unfamiliarity with the host culture. However, as they engaged in collaborative research and lesson design, their appreciation for cultural diversity deepened. One candidate remarked, “Planning the class made me question myself a lot more than usual class plans since I had to consider cultural differences. Through the process, my attitude toward being careful with multicultural students enhanced”.

Candidates also demonstrated proactive efforts to understand and navigate cultural nuances. For instance, one teacher shared, “I also watched some videos of American school classes, and it helped me learn how to adapt to another culture’s non-verbal language of the teacher”. This initiative not only improved their lesson planning but also fostered a more nuanced understanding of teaching in multicultural environments.

Furthermore, the experience of preparing lessons in a non-native language prompted candidates to reflect critically on both their own and others’ cultures. As one participant noted, “I got another experience of preparing a lesson using a language that is not my mother language, and I could think about not only researching my culture but also someone else’s culture. I believe this experience will enhance my cultural competence”. This reflection illustrates the program’s transformative impact on enhancing motivational CQ.

As presented in Table 11, motivational CQ scores increased significantly post-program, with notable improvements across most survey items. Interestingly, Korean teacher candidates exhibited greater gains than their American counterparts, ultimately surpassing them in overall mean scores. While American candidates initially scored higher on specific items, some experienced slight declines—particularly on item 13—suggesting challenges in sustained engagement with unfamiliar cultures.

Table 11.

Responses to motivational CQ items.

These findings align with Peng et al. (2015), who found that motivational CQ significantly predicted cross-cultural adaptation and psychological comfort among study-abroad participants, particularly when supported by a strong cultural identity. Similarly, Alexander et al. (2021) reported that intensive, experiential cultural development programs led to substantial increases in cognitive, metacognitive, and behavioral CQ, though gains in motivational CQ were limited—a pattern mirrored in our study. A recent systematic review also highlighted that motivational CQ is more resistant to change without prolonged or structured interventions (Alexander et al., 2021; Urgun et al., 2025).

Thus, the observed divergences between American and Korean participants underscore the importance of continuous cultural training and ongoing engagement to nurture motivational CQ effectively. The CSN program’s emphasis on motivational CQ—through immersive interaction and reflective practices—was instrumental in fostering teacher candidates’ confidence, cultural curiosity, and readiness to embrace diversity in their teaching practices.

3.2.4. Behavioral Cultural Intelligence (CQ)

Behavioral cultural intelligence (CQ) is a crucial skill for educators, as it reflects their ability to modify verbal and nonverbal behaviors to interact effectively with individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds (Van Dyne et al., 2008). This adaptability is essential for fostering meaningful communication and mutual understanding in multicultural educational settings.

The CSN program, conducted primarily in English, presented communication challenges—particularly for Korean teacher candidates who were less fluent than their American peers. Despite this, interactions between participants were largely successful and enriching. As one candidate shared, “Cooperating with students from different countries helped me develop cultural competence by communicating in a different language and sharing what we know about our culture”. This quote illustrates the dual nature of language as both a barrier and a bridge in intercultural exchange.

Digital tools such as Padlet, Zoom, and Microsoft Teams played a significant role in supporting communication. For example, Padlet enabled participants to share lesson plans and cultural insights in advance, allowing Korean teachers time to understand their American counterparts’ perspectives. One candidate reflected, “By posting our lessons and providing feedback on Padlet, we were able to interact with future STEM teachers from other cultures and learn about their cultural concepts”. This structured, asynchronous format helped facilitate collaboration and reduce linguistic and cultural gaps.

As shown in Table 12, behavioral CQ improved among teacher candidates following the program. American participants demonstrated adaptability by modifying their communication strategies—such as slowing their speech, incorporating pauses, and adjusting nonverbal cues like facial expressions (items 17–20). While Korean teachers exhibited slightly smaller gains, they made commendable efforts to adjust their verbal communication styles (item 16), reflecting a willingness to bridge cultural divides.

Table 12.

Responses to behavioral CQ items.

One candidate noted, “Padlet allowed us to take the time needed to accept an unfamiliar culture. I could briefly explain our culture to them”. Such reflective practices contributed not only to the development of behavioral CQ but also to a greater appreciation for cultural diversity. Ultimately, these interactions fostered a more inclusive and collaborative learning environment.

4. Discussion

The Cultural STEM Night (CSN) initiative demonstrated statistically significant improvements in key outcomes for both American and Korean teacher candidates, particularly in STEM identity, self-concept, values, personal interest, attitudes, and overall cultural intelligence (CQ). These findings support a growing body of literature advocating for the integration of culturally responsive pedagogy (CRP) into STEM education as a means of enhancing equity, engagement, and learning outcomes (Gay, 2010; Hammond, 2015). In line with the concerns outlined in the introduction—namely, that minority students often disengage from STEM due to a lack of culturally relevant content (Thevenot, 2021; Ladson-Billings, 1995)—CSN provided teacher candidates with concrete strategies to design inclusive STEM lessons rooted in the lived experiences and cultural backgrounds of diverse learners.

The CSN model responds directly to calls for equity in STEM education (National Academies of STEMs, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018), as it cultivates teachers who are both subject-matter competent and culturally responsive. The program’s collaborative design encouraged participants to reflect on systemic inequities and their own instructional approaches. Reflections from teacher candidates revealed a heightened awareness of the importance of affirming student identities in STEM content and a commitment to integrating culturally relevant strategies into their future teaching.

Notably, while cognitive and behavioral dimensions of cultural intelligence showed measurable gains, motivational CQ did not significantly improve. This aligns with previous research suggesting that deeper forms of engagement, such as motivation to act cross-culturally, often require sustained, meaningful interaction (Van Dyne et al., 2008). Given that each teacher candidate had only 15–20 min of interaction per group during the CSN event, the limited duration may have impeded the development of this dimension. To address this gap, future iterations could incorporate longer engagement periods, mentorship continuity, or pre-event workshops to foster stronger emotional and motivational investment.

The program also addressed a key gap identified in the introduction: the limited implementation of culturally responsive teaching (CRT) in international teacher preparation programs. Through the partnership between American and Korean teacher candidates, CSN provided a meaningful platform for cross-cultural exchange and joint curriculum development. These experiences align with CRT principles by valuing diverse cultural perspectives, promoting collaborative learning, and encouraging self-reflection (Gay, 2018; Howard, 2010). Candidate reflections indicated improved instructional adaptability and confidence in navigating cultural differences, which are critical for preparing teachers to meet the needs of diverse student populations.

Technology played an essential role in enabling this international collaboration, consistent with the literature on the role of digital tools in global education (Enkhtur et al., 2024; Bond et al., 2021). Tools such as Padlet and Zoom facilitated synchronous and asynchronous collaboration, breaking down geographical barriers and allowing participants to engage in meaningful dialogue and shared lesson planning. This use of technology not only supported cross-cultural exchange but also enhanced digital literacy and communication skills among teacher candidates—competencies increasingly necessary in today’s technologically integrated classrooms (Örtegren, 2022).

Furthermore, CSN’s emphasis on culturally responsive STEM teaching has broader implications for student achievement. Research has consistently shown that when students see their cultural identities reflected in the curriculum, they are more engaged and perform better academically, particularly in underrepresented and minority populations (Eaton et al., 2020; Gutstein et al., 2013). The CSN initiative exemplifies how teacher training programs can serve as critical levers for promoting equity in STEM by empowering educators to design inclusive, culturally affirming lessons.

Finally, the CSN experience aligns with recommendations for effective professional development in CRT: it was collaborative, reflective, sustained over time, and supported by mentorship (Darling-Hammond et al., 2002; Milner, 2022). The program structure enabled teacher candidates to apply theoretical knowledge in real-world contexts, engage in intercultural dialogue, and receive targeted feedback—all of which are essential for meaningful growth in culturally responsive practice.

5. Conclusions

The cultural STEM night (CSN) initiative highlights the transformative impact of culturally responsive, interdisciplinary programs in STEM teacher preparation. By fostering collaboration between American and Korean teacher candidates, the program not only enhanced participants’ confidence and engagement with STEM instruction but also significantly improved their ability to design culturally inclusive and globally relevant learning experiences.

The results affirm the importance of embedding cultural relevance into STEM education as a means to promote student engagement, affirm identity, and narrow achievement gaps, particularly among students from underrepresented or marginalized communities. While gains in cognitive and behavioral cultural intelligence were evident, the lack of significant improvement in motivational CQ points to the need for more sustained or intensive intercultural engagement. Structuring longer interaction periods, integrating pre-program preparation, or extending mentorship beyond the event could enhance outcomes in future iterations.

Moreover, the study illustrates how educational technologies—such as Padlet, Zoom, and other online platforms—can facilitate meaningful international collaboration, overcoming logistical barriers and expanding access to professional development. These tools proved essential not only for instructional planning but also for cultivating digital fluency and intercultural communication skills among future educators.

The CSN initiative serves as a scalable and replicable model for promoting culturally responsive teaching (CRT) in STEM education. Its success underscores the need for continued investment in CRT-focused teacher training, collaborative international partnerships, and technology-enhanced learning environments.

Future research should examine the longitudinal effects of culturally responsive STEM programs on teaching practices and student outcomes, explore pathways for broader adoption across diverse educational contexts, and investigate systemic strategies—such as policy initiatives and curriculum reforms—that embed CRT into STEM education at scale. Such efforts are vital for building a more equitable, inclusive, and globally competent STEM education system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Y.; methodology, J.Y.; project administration, J.Y. and H.L.; funding acquisition, J.Y.; formal analysis, J.Y.; investigation, J.Y. and H.L.; data curation, J.Y., H.L. and J.M.; supervision, J.Y. and H.L.; writing—review and editing, J.Y., H.L. and J.M.; resources, J.Y. and H.L.; validation, J.Y., H.L. and J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) program by the Texas International Education Consortium (TIEC) and the CARES grant of University of Texas Arlington.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas at Arlington (protocol code EX-2023-0426, approved on 11 October 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to the Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) program by the Texas International Education Consortium (TIEC) and the CARES grant of University of Texas Arlington for their support in facilitating our cross-cultural STEM collaboration. Their resources and guidance enabled meaningful connections and fostered culturally responsive teaching, enriching our project and advancing global education. Thank you for making this impactful initiative possible. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4, July 2025) for assistance with editing and language refinement. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CSN | cultural STEM night |

| STEM | science, technology, engineering, and mathematics |

| CRT | culturally responsive teaching |

| CRP | culturally relevant pedagogy |

| CQ | cultural intelligence |

| CQS | cultural intelligence scale |

| TEKS | Texas essential knowledge and skills |

| OER | open educational resources |

References

- Alexander, K. C., Ingersoll, L. T., Calahan, C. A., Miller, M. L., Shields, C. G., Gipson, J. A., & Alexander, S. C. (2021). Evaluating an intensive program to increase cultural intelligence: A quasi-experimental design. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad, 33(1), 106–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, S., Van Dyne, L., Koh, C., Ng, K. Y., Templer, K. J., Tay, C., & Chandrasekar, N. A. (2007). Cultural intelligence: Its measurement and effects on cultural judgment and decision making, cultural adaptation and task performance. Management and Organization Review, 3(3), 335–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autodesk. (2020). Tinkercad. Available online: https://www.tinkercad.com (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Barbera, J., Adams, W. K., Wieman, C. E., & Katherine, K. (2008). The Colorado learning attitudes about STEM survey: Modification and validation for use in chemistry. Researchgate. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237381629_The_Colorado_Learning_Attitudes_about_STEM_Survey_Modification_and_Validation_for_Use_in_Chemistry (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Bond, M., Bedenlier, S., Marín, V. I., & Händel, M. (2021). Emergency remote teaching in higher education: Mapping the first global online semester. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 18(1), 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D., & Stanley, J. (1963). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research (R. McNally, Ed.). Cengage Learing. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, L., Chung Wei, R., Andree, A., & Liu, E. (2002). Powerful teacher education: Preparing professional educators for 21st century schools. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff, D. K. (2009). Implementing intercultural competence assessment. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 477–491). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton, A. A., Saunders, J. F., Jacobson, R. K., & West, K. (2020). How gender and race stereotypes impact the advancement of scholars in STEM: Professors’ biased evaluations of physics and biology post-doctoral candidates. Sex Roles, 82, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enkhtur, A., Zhang, X., Li, M., & Chen, L. (2024). Exploring an effective international higher education partnership model through virtual student mobility programs: A case study. ECNU Review of Education, 7(4), 971–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatayan, A. (2024). Analyzing the impact of Google earth on the learning motivation of elementary school students. ETDC: Indonesian Journal of Research and Educational Review, 3(2), 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, N. A., & Santana, M. C. (2017). SCCT and underrepresented populations in STEM fields: Moving the needle. Journal of Career Assessment, 25(1), 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, G. (2010). Culturally responsive teaching in theory and practice. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gay, G. (2018). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice (3rd ed.). Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gutstein, T., Miller, R., & Nasir, N. S. (Eds.). (2013). Equity and access for all: A critical perspective on gifted education. TPL Educational Services Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, Z. (2015). Culturally responsive teaching and the brain: Promoting authentic engagement and rigor among culturally and linguistically diverse students. Corwin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, T. J. (2010). Why theories of culture matter in teaching mathematics. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 13(4), 311–329. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, B., Onwuegbuzie, A., & Turner, L. (2007). Toward a definition of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(2), 112–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. (2022). Korean STEM teachers’ perceptions in PISA survey: Focusing on comparison with the United States and China. Journal of the Korean Chemical Society, 66(1), 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, Y. (2018). Effects of educational context variables on STEM achievement and interest in TIMSS 2015. Journal of the Korean Association for STEM Education, 38(2), 113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Culturally relevant teaching, education that affirms difference. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Milner, H. R., IV. (2022). Culturally relevant STEM teaching professional development: A case study of middle school teachers’ perspectives on confidence and implementation. Journal of Research in STEM Teaching, 59(2), 374–403. [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of STEMs, Engineering, and Medicine. (2018). A framework for K-12 STEM education: Practices, disciplinary ideas, and crosscutting concepts. The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2022). State educational agency (SEA) discretionary grants program. Available online: https://ed.gov/fund/grants-apply.html (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Collins, K. M. (2007). A typology of mixed methods sampling designs in social science research. The Qualitative Report, 12(2), 474–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örtegren, A. (2022). Digital citizenship and professional digital competence—Swedish subject teacher education in a postdigital era. Postdigital Science and Education, 4, 467–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, A. C., Van Dyne, L., & Oh, K. (2015). The influence of motivational cultural intelligence on cultural effectiveness based on study abroad: The moderating role of participants’ cultural identity. Journal of Diversity Management, 10(2), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, K., Adams, W., Dubson, M., Finkelstein, N., Reid, S., Wieman, C., & LeMaster, R. (2006). PhET: Interactive simulations for teaching and learning physics. The Physics Teacher, 44(1), 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, J. (2017). Embedding collaborative online international learning (COIL) in higher education: Latest research and implications. In R. O’Dowd, & T. Lewis (Eds.), Online intercultural exchange: Policy, pedagogy, practice (pp. 259–264). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, C. K. S., Zaini, M. F., Chenderan, K., Gopal, R., Shukor, S. S., Madzlan, N. A., & Khalid, P. Z. M. (2023, June). Exploring the use of Jamboard, Padlet and Canva as teaching apps for the digital classroom. In AIP Conference Proceedings (Vol. 2750, No. 1, p. 040008). AIP Publishing LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Thevenot, Y. (2021). Culturally responsive and sustaining STEM curriculum as a problem-based science approach to supporting student achievement for black and latinx students. Voices in Urban Education, 50(1), 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urgun, M., Seidel, T., Vangeli, N., Borges, T. O., & de Oliveira, L. B. (2025). Exploring the impact of cross-cultural training on cultural competence and cultural intelligence: A narrative systematic literature review. Sports, 8(1), 100622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyne, L., Ang, S., & Koh, C. (2008). Development and validation of the CQS: The cultural intelligence scale. In S. Ang, & L. Van Dyne (Eds.), Handbook of cultural intelligence: Theory, measurement, and applications (pp. 16–38). ME Sharpe. [Google Scholar]

- Villegas, A. M., & Lucas, T. (2002). Schooling for diversity: Education in a changing society. Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds.). Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A. I., & Tahir, R. (2020). The effect of using Kahoot! for learning—A literature review. Computers & Education, 149, 103818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J., Ko, Y., & Lee, H. (2022). Virtual and Open Integration of Culture for Education (VOICE) with science teacher candidates from Korea during COVID-19. Asia-Pacific Science Education, 7(2), 384–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J., & Martin, L. (2019). Infusing culturally responsive science curriculum into early childhood teacher preparation. Research in Science Education, 49(3), 697–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).