Abstract

This article explores the implementation of a tandem course that integrates gamification and interactive teaching methods and investigates how this model affects teacher motivation and participant engagement, particularly in higher education contexts. This study also highlights the potential of tandem teaching beyond its traditional use in language learning and provides qualitative and quantitative insights into the experiences of both course participants and educators, showing how collaborative, gamified teaching strategies can inspire more effective, student-centered pedagogy. It examines how the course was developed, the outcomes in terms of teachers’ engagement and the enhancement in learning experiences, and proposes a new perspective on how education can be restructured. The study emphasizes that traditional, lecture-based teaching is no longer sufficient in engaging modern learners and teachers too. By adopting more digital, student-centered approaches, we suggest that subjects can be reimagined as more interactive and teacher–student-friendly. The main question stated in the article sounds like the following: “How does gamification and interactive teaching methodologies, like tandem course, affect teacher and participant engagement and motivation?”. To address this question, a study was conducted based on the tandem course titled “Gamification in the learning process and interactive teaching methodologies” prepared within the FORTHEM Alliance by three united universities. It was delivered online during four meetings in May 2024.

Keywords:

creative teaching; educational methods; gamification; teacher motivation; tandem course; long-life learning JEL Classification:

JEL A20

1. Introduction

Nowadays, people in general, but students as well, seem to struggle with a lack of motivation and engagement for learning. Traditional lecture-based instruction often presents a high volume of information, which can be difficult for students to process effectively. This cognitive overload can hinder learning and contribute to a decline in students’ intrinsic motivation. The increasing adoption of gamification and game-based learning in educational settings reflects a growing need to address limitations in traditional, lecture-centered teaching. Studies suggest that these methodologies can enhance student engagement and motivation by creating more dynamic and interactive classroom experiences (F. Chen et al., 2025; Qasim et al., 2024). However, while much research has focused on student outcomes, the impact of gamification and collaborative teaching methods on educators’ motivation and professional engagement remains underexplored. This study examines a tandem course on gamification and game-based learning, collaboratively developed by university teachers for teachers, to investigate how this approach may influence teachers’ motivation and classroom innovation in academia.

The tandem course model allowed educators to work jointly in designing and implementing gamified instructional strategies, fostering a supportive environment where both course facilitators and participants engaged deeply with interactive teaching methods. By creating a shared space for collaboration and idea exchange, the course encouraged educators to explore new ways of integrating gamified elements into their teaching practice.

Preliminary findings indicate that the tandem course structure positively influenced both facilitators and participants, enhancing motivation and enthusiasm for adopting gamification in educational settings. Nevertheless, to fully understand the potential of tandem courses and their long-term effects, further research is needed. This study contributes to a growing body of the literature on teacher motivation and collaborative learning models, providing a foundation for future studies on the role of gamification and teacher collaboration in evolving pedagogical practices to meet contemporary educational demands.

2. Tandem Course as a Teaching Tool—Literature Review

Traditionally, the concept of tandem course has been associated with language learning, as one of the ways to learn a foreign language in authentic intercultural communication contexts (Porshneva et al., 2020). These experiences have been found to support the sociocultural well-being of international students and enrich academic curricula through intercultural exchange (Almazova et al., 2020). Language tandem programs are particularly valued for promoting informal learning environments, encouraging dialogue, and easing the sociolinguistic adaptation of students in multicultural academic settings (Szyszka et al., 2018).

In contemporary higher education, there is a growing trend of student participation in international academic experiences. Among these, the research tandem model is increasingly recognized as an innovative approach to collaborative learning and transnational academic partnership (Tateo et al., 2024; Appel & Mullen, 2000). This sets a challenge to educational institutions to develop new ways and methods in support of international students’ sociocultural and linguistic adaptation. In this regard, tandem language learning could be considered as an effective tool in complementing formal education at university level as it helps create a positive learning environment and involves students in new academic experiences (Almazova et al., 2020). The notion of a mutually supportive partnership is central to tandem learning (White, 2012).

Faculties members from different countries need to work closely together to align their course objectives and assignments, as teacher tandems have been recognized as one of the most effective methods to integrate foreign teachers in the process of professional training (Porshneva et al., 2020). Tandems encourage teachers and students to share knowledge of professional and intercultural communication strategies and different visions of the world.

Tandem courses are an innovative teaching tool to develop critical thinking, foster interdisciplinary learning, enhance collaboration skills, improve problem-solving abilities, and boost student engagement and motivation (Schug & Torea, 2023). Designing the program in a tandem course requires insights from all partners involved, and this challenge helps participants to appreciate the value of all tandem partners in academia (Laanemaa et al., 2023; Lu et al., 2024). Tandem course offers the benefits of authentic, culturally grounded interaction, while also promoting a pedagogical focus among participants (O’Rourke, 2005). Reflections and the end of the experience help all participants process and synthesize the material from different perspectives.

Tandem course design is a collaborative, cross-institutional approach to curriculum development in which educators from different universities and disciplines jointly create a shared course framework (in this case, a gamified learning experience) that each will implement in parallel within their own classrooms. Unlike traditional team teaching—where two or more instructors co-teach the same student group simultaneously (Buckley, 2000)—tandem design involves shared planning and design without co-delivery, yielding a unified pedagogical structure that is adapted and taught locally at each institution. This concept builds on prior work in co-design and collaborative curriculum development, positioning instructors as co-creators of the course rather than solitary implementers, and it is rooted in social constructivist principles that view knowledge building as a shared, dialogic process (Voogt et al., 2015). The collaborative design process not only produces common course materials but also serves as a form of professional development for the educators: working in tandem enables reflective dialogue, mutual learning, and a sense of joint ownership that can reinvigorate teachers’ motivation and engagement (e.g., by sparking pedagogical innovation and nurturing a community of practice) (Zeivots et al., 2024). Furthermore, the tandem design model aligns with design-based research ideals by allowing iterative refinement and study of the jointly developed course across multiple real-world contexts. In the present study’s context, the gamified course co-created through tandem design was intended to enhance student engagement and intrinsic motivation by incorporating game elements that satisfy learners’ needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Rutledge et al., 2018)—an approach consistent with self-determination theory’s framework for fostering motivation. In sum, tandem course design refers to an innovative course development paradigm distinguished by interdisciplinary, multinational educator collaboration in the design phase and parallel deployment of the resulting course, in contrast to standard single-instructor design or in-class team teaching (Zeivots et al., 2024; Buckley, 2000).

3. Implementing Tandem Courses Beyond Language Learning

Based on recent publications dealing with tandem issues, it can be noticed that it is mainly presented as a language teaching tool (Porshneva et al., 2020; O’Rourke, 2005; Appel & Mullen, 2000; Krompák & Hartmann, 2023). But looking at the potential of this tool, we believe that it can be used not only for linguistic purposes. In fact, it can be used as a multidisciplinary tool whenever there are several subjects involved. As the general definition of tandem says, if someone does something in tandem with someone else, they do it together or at the same time. It confirms this aforementioned statement. Considering the three principles behind tandem learning, which are bilingualism; reciprocity (behavior in which two people or groups of people give each other help and advantages); and learner autonomy, it can be stated that it is not dedicated only to language teaching. Unfortunately, such an attitude is not popular among scientists and leaves a gap that we would like to fill. This underutilization of tandem methodologies outside language education is echoed in current research advocating for integrating tandem principles across STEM and vocational training (Dahalan et al., 2024), as well as inclusive education contexts (Jovanović, 2023). These perspectives offer a strong case for broader curricular incorporation.

While researching guidelines regarding the design of a tandem course, we found different inspirational articles about language learning tandem courses, focused on conversational practice and cultural exchange, and inputs about the teacher’s role in virtual classroom tandem course (Hansell et al., 2021). These language courses are often structured so that participants can teach each other, usually focusing on their native languages, while benefiting from the experience of practicing a foreign language. “The principles of tandem allow participants to organize exchanging and sharing their communicative experience, their knowledge and their strategies based on the knowledge of the partner’s mother tongue and culture”. The tandem method of co-teaching and co-learning, when applied face-to-face, offers an effective approach to language acquisition and professional development. It emphasizes mutual help, cooperation, and spontaneous interaction between learners, fostering a dynamic learning environment (Porshneva et al., 2020, p. 760; Antala et al., 2023), demonstrating that tandem teaching also contributes to curricular reform, emphasizing co-creation and shared learning values across disciplines. These findings underscore the broader relevance of the tandem model, which extends well beyond language learning into broader pedagogical innovation.

Well-structured tandem courses can be powerful teaching tools to make learning more dynamic and applicable to real-world contexts and different academic environments (Vinagre, 2007). They provide the opportunity for collaboration between teachers across the world, enhancing not only teaching strategies and research skills, but also providing participants with learning experiences across cultural and disciplinary boundaries. By engaging in a tandem learning model, participants can explore knowledge through access to international and interdisciplinary contexts (Krompák & Hartmann, 2023).

Considering the lack of guidance regarding the tandem teaching model (Howard, 2024), designing the tandem course about gamification was both rewarding and challenging at the same time. The expertise of each teacher involved in the tandem course brought a unique perspective on gamification, fostering an interdisciplinary and intercultural learning experience for both the participants and the teachers themselves (Appel & Mullen, 2000).

This approach emerged as a transdisciplinary exploration of gamification, where it was at first presented as a tool for teaching and learning processes, but also revealed as transferable to real-life situations for any participant. Far beyond expectations, the preparation for the tandem course became not only an inspiring environment for the teachers involved, but it also enhanced collaboration and practical learning and revealed new possibilities and insights regarding the integration of gamification in diverse areas (Jovanović, 2023; Howard, 2024). Just like collaborating with partners from different disciplines or countries can provide broader perspectives on a research topic, skills-oriented tandem courses foster creative approaches to a subject and equip students for diverse, interdisciplinary career paths (Bruen & Sudhershan, 2015; Batardière & Jeanneau, 2020).

The tandem course organized by different universities emphasizes immersion and interpersonal connection between international colleagues, which can enhance both learning experiences proficiency and cultural empathy (Almazova et al., 2020). The entire effort to build such a creative and engaging learning experience could function if it is based on values, for all partners, like co-creation, cooperation, motivation, creating community, diversity, and a global educators network, according to recent research (Abegglen et al., 2023).

4. Gamification and Game-Based Learning as a New Element of Teaching Process

In recent years, gamification has been widely used in education, and it has emerged as a dynamic and rapidly evolving field of research (Swacha, 2021). Recent studies proved that gamification influences students’ study engagement through the indirect effects of enjoyment and self-efficacy (J. Chen & Liang, 2022; Prieto-Andreu et al., 2022). People play games while traveling, unwinding, or at work to generate delightful experiences. In the modern day, where social media and digital technology mediate most of what we do, many schools and firms shift that behavior by transforming routine tasks into rich, fun, gaming-like experiences (W. Wang et al., 2021). This process is called gamification (Robson et al., 2015).

Gamification is used in various fields, including education, marketing, employee training, health, wellness, physical education, and customer engagement. Recent studies that evaluated the empirical findings of the state-of-the-art literature in the emerging field of gamification within the educational domain of learning and instruction reveal three relevant positive effects like students’ engagement and motivation, academic achievement, and social connectivity (Zainuddin et al., 2020). However, research on gamification still faces a variety of empirical and theoretical challenges (Rap et al., 2019). Educational applications might use gamification to make learning more engaging for students, while businesses might use it to improve employee performance, encourage customer loyalty, or reward employees and customers (Banfield & Wilkerson, 2014). Current investigations into vocational and professional training (Dahalan et al., 2024) demonstrate that gamified strategies contribute to measurable gains in student engagement, self-directed learning, and transference of skills to real-world tasks. Moreover, studies focusing on student motivation in physical education have confirmed increased motivation levels “and commitment toward physical exercise in students” (Arufe et al., 2022b). Successful gamification requires an understanding of target audiences, their motivation, and the context in which the strategy is applied. At every stage of education, the core objective of gamification stays the same: to create a rich learning environment in which gamification serves as a driving force that enhances both personal and collective learning experiences (Christopoulos & Mystakidis, 2023).

To ensure new, engaging, and attractive learning environments and the effectiveness of teaching, teachers and researchers all over the world focused on finding new attractive tools for engaging students in the learning process and involving new resources in their teaching process. The process of teaching–learning suffered some change and “among the strategies that have been implemented are gamification and game-based learning” (Fonseca et al., 2023). Findings confirmed the benefits that games can provide in teaching and learning efforts, like improving “academic performance, engagement, and motivation in vocational education learners” and even though there is a need for research “to determine the gamification strategies that are most suited for vocational education and learning” (Dahalan et al., 2024), it became possible to classify and define games’ appearances in educational contexts. In this article, we refer to the difference between game-based learning and teaching and gamification by revealing the way they are applied in class and their purpose. When used in the teaching process, educational games are designed to serve specific educational goals or learning outcomes; cooperative games, for example, can help enhance knowledge and generate pro-environmental engagement alongside students (Vázquez-Vílchez et al., 2021).

Gamification is an innovative constructivist approach to learning, according to recent research (Roodt & Ryklief, 2019) that has gained significant attention in different areas, including education (Manzano-León et al., 2021; D. Wang et al., 2021). The definition of gamification consists of “game-based mechanics, aesthetics and game thinking to engage people, motivate action, promote learning, and solve problems” (Kapp, 2012). Everything that is part of creating a game is considered as a “game element” (Dahalan et al., 2024). Recent studies show that a wide range of game elements have been used in designing games (Man, 2021). Other research mentions that game elements are organized in a hierarchy of components, mechanics, and dynamics (Werbach & Hunter, 2012). Most of the gamification implementation incorporates game elements like avatars, points, badges, and leaderboards. There is evidence that suggests that digital game elements are used in education to achieve specific learning goals and to engage participants to enjoy the learning process (Gupta & Goyal, 2022). Gamification in education injects game elements into learning environments, aiming to enhance engagement, motivation, and ultimately, learning outcomes (Qasim et al., 2024). Designing successful gamification tools in education and discovering how they influence the behavior, motivation, and attitudes of students, and the learning outcomes, are still under research (Dahalan et al., 2024).

Game-based learning is a different concept that refers to fun learning through doing/playing and specifically designed, structured game learning materials that can stimulate the development of thinking skills and self-learning among vocational students (Azizan et al., 2021). The definition is focused on the union of educational learning theories, course curricula, and digital gameplay, with the specific goal of enhancing the learning experience of participants (Jayasinghe & Dharmaratne, 2013; Roodt & Ryklief, 2019). Lots of recent studies argued about the benefits of game-based learning, especially improved motivation, engagement, satisfaction, and academic achievement among students (Arnold et al., 2021; Oliveira et al., 2021; Dahalan et al., 2024; Roodt & Ryklief, 2019). Based on the results of the longitudinal experiment carried out by Lampropoulos and Sidiropoulos, it was proved that gamified learning was the most effective approach in comparison to traditional and online learning (Lampropoulos & Sidiropoulos, 2024).

Regarding game-based learning in practice, the learning experience and the games are becoming the lesson or a part of it. They are serving the content of the curricula and purchasing educational goals. Overall, while game-based learning demonstrates considerable potential in enhancing education, its successful implementation requires careful consideration of age-appropriateness, varied game types, and the integration of emerging technologies like AR (Mikrouli et al., 2024). Games are also recognizable by their framework and specific objectives; whether gamification is about how some specific game elements are used in the teaching and learning process, not only to stimulate motivation alongside students, but also to ensure effectiveness and generate a playful and joyful learning environment. The game elements are “added to the traditional instruction method” or used alongside game-based learning. Gamification’s efficacy is increasingly validated through neuroscience-informed pedagogies that emphasize reward-driven engagement and the impact of immediate feedback loops on cognitive anchoring (Manzano-León et al., 2021; Prieto-Andreu et al., 2022). Regarding the educational field, gamification can be “defined as a strategy that uses elements designed for the game in non-game contexts” (Fonseca et al., 2023).

Both gamification and game-based learning are nowadays leading trends in education as innovative technology (Dahalan et al., 2024). Even if they are similar and both have relatively comparable goals, still they are two distinct techniques with multidimensional relationships (Jayasinghe & Dharmaratne, 2013; Krath et al., 2021). Gamification and game-based learning are different in specific ways: game-based learning incorporates games seamlessly into the educational curriculum to achieve specific learning outcomes, while gamification involves changing the entire learning process into a game using game elements, for example, levels, points, badges, leaderboards, quests, social graphs, or certificates (Krath et al., 2021). The main difference between games and other interactive methods, including gamification, lies in the presence of a specific goal and the achievement of a certain game result. However, achieving this result is not an end but solely a means for deeper analysis, meaningful self-reflection, integration of knowledge into one’s inner world, and, most importantly, for the development and consistent training of specific skills. Both strategies aim to encourage participants and increase learning with the use and the benefits of game-based ideas and tactics (Dahalan et al., 2024) and foster “key competencies of learners, such as problem solving, collaborative communication, and strategic thinking” (Hou, 2023).

Using gamified design in teaching has made important contributions to theory and practice (J. Chen & Liang, 2022). The application of gamified design teaching can make learning more interesting, make students more active in learning, and make teachers use more initiative in teaching. Recent research argues that gamification strategies can be a powerful tool in education to boost students’ engagement, productivity, and motivation, showing game elements’ affordances as impacting gamification’s motivational effects (Roy & Zaman, 2018; Kim et al., 2018). Game-based learning and e-learning have transformed education, making learning more interactive and even fun. Gamified learning platforms provide immediate feedback, progress tracking, and rewards to motivate students (Hanus & Fox, 2015). Gamification is all about making non-game activities feel like they are games. It is a way of adding extrinsic motivation—dangling rewards like carrots on sticks—to enhance participation and productivity (Arufe et al., 2022a). Recent studies of a systematic meta-review of theoretical foundations in gamification, serious games, and GBL research show that the use of this pedagogical approach in the field of teacher training is still scarce, although it is growing exponentially (Krath et al., 2021). Thus, there is a great opportunity for educational institutions to adopt this pedagogical innovation to improve the training of future teachers (Guerrero Puerta, 2024).

5. “Gamification in the Learning Process and Interactive Teaching Methodologies” as an Example of Tandem Course Implementation

5.1. Description of Tandem Course

A tandem course titled “Gamification in the learning process and interactive teaching methodologies” was developed through the Forthem Alliance by three collaborating institutions: the University of Latvia (UL), “Lucian Blaga” University of Sibiu (Romania, ULBS), and University of Opole (Poland, UO). The course was delivered synchronously online and divided into four modules—ULBS was responsible for the first one, UO for the third one, and UL for the second and fourth. Participants were awarded 1 ECTS point.

The first module titled “Gamification in the teaching and learning process” was prepared and led by the University of Lucian Blaga. It was aimed at describing the necessity of adapting teaching practices to meet the needs of today’s learners and sustaining their attention during academic classes. Recent studies indicate that gamification can enhance participant engagement and excitement (Arufe et al., 2022a; Dahalan et al., 2024). The module was focused on analyzing theoretical arguments that support the relevance of gamification in educational settings. Participants explored how to integrate specific gamification mechanisms into online communication, incorporating enjoyable elements to enhance the learning process’s benefits.

The second part titled “Business Simulation Games: Interactive Solution to Challenges Posed by AI in Education” was prepared and led by the University of Latvia Professional Development Academy. It examined the transformative impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) on education and addressed the challenge it poses to traditional teaching methods. This part advocated for the integration of interactive and engaging business simulation games as an effective solution to enhance learning experiences. Participants could have learned to optimize their teaching time while maximizing the development of learners’ skills and knowledge. Key outcomes included sharing methodologies of business simulation games, understanding the principles of long-term memory retention, and creating engaging learning environments.

Since 1992, the University of Latvia has been using business simulation games created by Professors Edgars Vasermanis and Daina Skiltere (Šķiltere, 2015). Irina Bausova played an important role in testing and using these games in classrooms. Over 5000 students and adult learners have participated in these simulations. The games started as paper-based, moved to Excel in 2020, and by 2022, six of them were fully digitalized and are now available worldwide. The digitalization of games and video instructions has reduced the time required to prepare teachers for integrating games into the teaching methodology of a subject. The business simulations of the University of Latvia are designed to teach skills like strategic thinking, business planning, decision-making in uncertain situations, and staying resilient under stress. Players practice financial decision-making and strategic planning in realistic, interactive scenarios while competing with others. These games help participants better understand key concepts in economics, financial literacy, entrepreneurship, and logistics. For educators, these simulation games serve as a facilitation tool in the classroom to capture students’ attention and positively impact their knowledge acquisition. They also make the classroom environment more enjoyable for teachers while saving time on preparing engaging and interactive solutions.

The third module titled “Games for Teaching Economics: Exploring Behavioral Aspects in Classroom Applications” was prepared and delivered by the University of Opole. It aimed at presenting teaching through simulation as a core component of learning supplemented by reflective discussions following gameplay. In this module, educators examined which competencies are developed through the use of board games in economics instruction. Case studies explored the use of online and board games in economics, including the implementation of virtual economies where players engage in creator-designed scenarios. Participants also learned about the behavioral aspects of using games in classes, how they influence the decision-making process of learners, as well as learned about the decision-making errors and pitfalls—what are the most common mistakes people make while making decisions and how to avoid them.

The final module was an interactive workshop titled “Implementation of Business Simulation Games into teaching practice”. It was an interactive part for educators, designed to consolidate the knowledge and skills acquired during the course and to brainstorm the implementation of interactive teaching methodologies into teaching practice. Through collaborative activities, educators learned how to effectively integrate interactive tools and methodologies into their curriculum to enhance student engagement and comprehension. The session, guided by experienced facilitators, offered practical, actionable techniques.

5.2. Research Methods

This part of the study was focused on implementing and analyzing the impact of a tandem course designed for trainers on gamification in education. The course adopted the tandem method as its central pedagogical approach, emphasizing cross-country collaboration to enhance motivation and enrich the learning experience. This qualitative study was carried out to gather in-depth insights into the participants’ experiences and assess the effectiveness of this approach in professional development contexts.

Participants included trainers from diverse educational backgrounds, selected from multiple countries to ensure a wide range of perspectives. The cross-country design of the tandem method facilitated interaction between participants with varying cultural and educational experiences, fostering a rich exchange of ideas.

Diagnostic survey research is the best method for obtaining original data to describe a population too large to study directly. It is also an excellent method for measuring attitudes and beliefs in a large population (Babbie, 2008). Data was collected through a well-structured questionnaire administered to participants at the end of the course. The questionnaire was designed to capture detailed feedback about the tandem method, the gamification content, and the overall learning experience. It included open-ended and Likert scale questions focusing on the following:

- Perceived effectiveness of the tandem method.

- Impact of cross-country collaboration on motivation and learning.

- Practical applicability of gamification strategies learned.

- Suggestions for improving the course design.

Participants were informed about the purpose, scope, and objectives of the research prior to their involvement. Participation was entirely voluntary, and participants were provided with detailed information outlining the nature of the study, potential risks, and their rights to withdraw at any point without consequence.

Written consent was obtained from each educator before data collection commenced. This consent covered participation in the questionnaire, as well as the possibility of follow-up interviews. To ensure anonymity and confidentiality, all data was anonymized during the transcription process, and identifying details were removed. Data was stored securely and only accessible to authorized researchers.

The use of qualitative methods—particularly questionnaires and interviews—was appropriate, as it enabled the exploration of complex, subjective experiences not readily captured by quantitative methods alone. The combination of qualitative and quantitative data provided a more holistic understanding of the tandem course’s impact. Furthermore, the open-ended nature of the questions enabled participants to express their thoughts freely, ensuring that diverse perspectives were adequately represented.

Responses were analyzed using qualitative methods. Open-ended items were examined through thematic analysis to identify recurring patterns and key themes. Quantitative data from Likert scale items was summarized using descriptive statistics to provide additional context to the qualitative findings.

The purpose of the study was to highlight the gaps both in theory and practice concerning tandem courses and particularly their novelty beyond the traditional language learning context. The main question stated in this survey sounded as follows: “How does gamification in the learning process and the use of interactive teaching methodologies, like tandem course, impacts teacher and participant engagement and motivation?”.

5.3. Perception of the Tandem Course by Its Participants

The tandem course was designed for life-long learners (LLLs) from all nine FORTHEM Alliance universities, who were teachers and students of pedagogical studies. A total of 74 application forms were filled in for the course, where 35 participants attended the first class (from them, each time there were different numbers of participants filling in the forms 33 (1st session), 22 (2nd session), 20 (3rd session), and 17 (last one and overall feedback of the course)). Finally, 24 participants successfully completed the course, submitted the final assignment, and received a certificate.

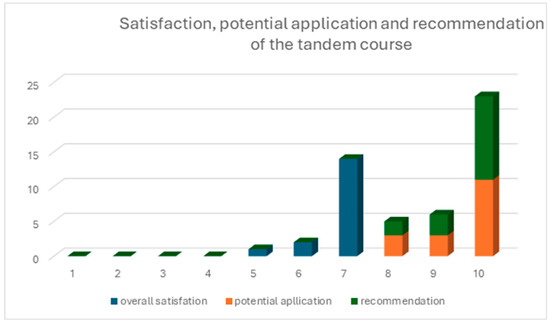

The first question addressed participants’ overall assessment of the course using a Likert scale form, where 1 was the minimum value and meant very unsatisfied, while 7 was the maximum and meant very satisfied. The second question concerned the issue of whether participants are likely to apply the knowledge gained on this course to their teaching practice and third, whether they are likely to recommend this course to a colleague. These two questions also had a Likert scale form, where 1 was the minimum value and meant very unlikely, while 10 was the maximum and meant very likely. The division of answers is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structure of responses for questions: 1. Overall, how satisfied were you with this course? (satisfaction); 2. How likely are you to apply the knowledge gained in this course to your teaching practice? (potential application); 3. How likely are you to recommend this course to a colleague? (recommendation) Source: own elaboration.

All answers were very positive, because the average value of answers for the first question was 6.75, very close to the maximum; for the second question, it was 9.47; and for the third 9.59. It is very optimistic that no one gave answers lower than 5 for the first and lower than 8 for the second and third questions. Concerning the satisfaction of participants, we can conclude that it was high: 59% of respondents awarded a maximum of 7 and the mean satisfaction was 6.4/7. Also, motivation to act, not just observe, was high: 68% rated 9 per 10 on the “apply in my teaching” scale (mean 8.8/10).

Semantic analysis has shown that gamification and emotions dominate the mental map. Top-frequency words in the “key ideas” answers were learning, games, gamification, students, feelings, and engagement. Peer exchange played a significant role as numerous comments referenced “ideas from other educators”, “sharing”, “community”, and mention concrete tools (Mentimeter, Genially, Classcraft).

Improvement suggestions were focused on smoother logistics and more resources. Improvement requests clustered around “one platform”, “less repetition”, and “compile a resource list/handbook”.

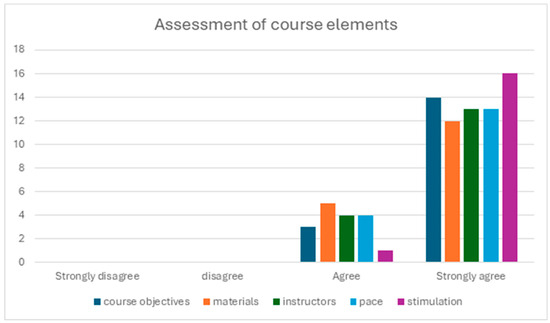

Further analysis of course feedback provided an overall positive impression of the activity. This was possible thanks to five questions. Participants were asked to assess to what extent they agree with the following statements:

- The course objectives were clear;

- The material presented was relevant and useful;

- The instructors were knowledgeable and engaging;

- The pace of the course was appropriate;

- The course activities stimulated my learning.

Possible answers were as follows:

- Strongly disagree;

- Agree;

- Disagree;

- Strongly disagree;

- Neutral.

The structure of all answers is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Structure of responses for the question “To what extent do you agree with the following statements: 1. The course objectives were clear, 2. The material presented was relevant and useful, 3. The instructors were knowledgeable and engaging, 4. The pace of the course was appropriate, 5. The course activities stimulated my learning”. Source: own elaboration.

These results were also very positive, because no one decided to disagree with any of the statements. Respondents were in general agreeing with them, and the majority strongly. The vast majority declared that this course was stimulating.

Despite the overwhelmingly positive feedback, participants also offered constructive suggestions for improvement:

- To provide more resources and ideas for games mentioned during all sessions;

- Recommended readings and maybe diverse resources to grasp complex topics more effectively;

- Engaging new futuristic view;

- More practical examples, also of how to use AI;

- Play one game practically;

- Arrange guest lectures or webinars with professionals from the gamification industry to provide valuable real-world perspectives and keep the course content relevant and up to date;

- More networking opportunities;

- Using the same platform for all the courses.

Some participants stated that no changes were needed and expressed complete satisfaction with the course. There were very positive comments like the following: “this course was useful and really helpful”, “It was a valuable experience”, “I’m glad that so many tools were used during the training”, “it was the most wonderful experience”, and “The course was excellent and highly engaging”. On the other hand, there were also participants who had critical comments like the following: “some information was repeated many times, it looked like educators didn’t know the agenda of others, some of them didn’t participate to avoid that situation. some examples/games were very specific, assigned to specific subjects/areas (…) it was very hard to listen and be active because of technical issues (noise) and no active components” or “Perhaps the gamification content has been focused on gamification but without an application in our classes. I’ve felt that sometimes there wasn’t appropriate for educators”.

The most popular and interesting responses were divided into three groups. The first set reflected Motivation and Engagement, i.e., as follows:

- “I can make my classes more interesting by applying challenges, checkpoints and badges for my students”;

- “Improve classes with gamification elements. Challenge students in a positive way”;

- “Gamification is applying game elements to learning activities; our face says a lot about how we feel”;

- “I will try to incorporate more feeling express exercises in my lessons. I will try to use gamification in math and history, and I will find a way to make it more attractive for the students”.

The second group included sentences reflecting Feelings of Support and Collaboration, like the following:

- “We do not need to be afraid to add some new things into our learning process. It is very important to try new ideas, then share these ideas with colleagues”;

- “The tandem course provided a supportive environment where I could connect with other teachers and share ideas”;

- “Sharing these challenges and overcoming them together with other participants has been one of the most valuable aspects”.

And finally, the third set of responses reflected Adaptation and New Methods:

- “Gamification can be used even in its minimal aspects (we can apply only the idea of competition on a learning task for instance), so it doesn’t necessarily have to be a whole structured process”;

- “To incorporate these practices into my teaching for Fall 2024, I will identify key subjects that benefit from gamification, set clear learning objectives, design engaging and interactive activities, integrate supportive technology, and develop assessments that measure both performance and engagement”;

- “Using group competitions to encourage collaboration and engagement among students”.

All these comments are useful and helpful while preparing for the next edition of the tandem course. Participants also provided some comments and opinions reflecting motivation and engagement, like the following:

- “I can make my classes more interesting by applying challenges, checkpoints and badges for my students.”

- “Improve classes with gamification elements. Challenge students in a positive way.”

- “Gamification is applying game elements to learning activities; our face says a lot about how we feel.”

- “I will try to incorporate more feeling express exercises in my lessons. I will try to use gamification in math and history, and I will find a way to make it more attractive for the students”.

There were also sentences reflecting feelings of support and collaboration:

- “We do not need to be afraid to add some new things into our learning process. It’s very important to try new ideas, then share these ideas with colleagues.”

- “The tandem course provided a supportive environment where I could connect with other teachers and share ideas.”

- “Using group competitions to encourage collaboration and engagement among students.”

- “Sharing these challenges and overcoming them together with other participants has been one of the most valuable aspects”.

Some sentences also reflected adaptation and new methods of teaching:

- “Gamification can be used even in its minimal aspects (we can apply only the idea of competition on a learning task for instance), so it doesn’t necessarily have to be a whole structured process.”

- “To incorporate these practices into my teaching for Fall 2024, I will identify key subjects that benefit from gamification, set clear learning objectives, design engaging and interactive activities, integrate supportive technology, and develop assessments that measure both performance and engagement.”

These reflections align with the growing evidence base that tandem learning models, particularly those supported by gamification, promote sustained changes in educator practice through increased perceived agency, peer validation, and motivational feedback loops (Gupta & Goyal, 2022; Abegglen et al., 2023). Participants’ opinions are very important as feedback from the effort put into preparing and leading the tandem course. It allows for the assessment of whether the planned learning outcomes have been achieved and what could be improved to achieve them to a better degree. Participants’ opinions also constitute a motivational element, as they arouse reflection in those conducting the courses regarding future editions.

5.4. Teachers’ Motivation in Numbers

The opinions of participants (long-life learners, LLLs) are undoubtedly important in the context of arousing motivation, but it is also worth looking at the motivation of teachers—the creators and course leaders themselves. For this purpose, a survey was developed, which was filled out by all the leaders about six months after the end of the classes. To testify teachers’ motivation, a structured interview was prepared and disseminated to capture the experiences and perspectives of the team members as creators of the tandem course. Almost all team members (7 per 8) completed the structured interview questions, reflecting the tandem course from both professional and multidisciplinary perspectives.

The set of interview questions dedicated to the creators of the tandem course consisted of five thematic units: 1. Motivations and expectations for participating in the tandem course, 2. Experiences and perceptions of collaborative, cross-institutional course design, 3. Challenges and benefits of working in a gamification-focused environment, 4. Perceived impact of the experience on professional identity, teaching practices, and future motivation, and 5. Reflections on lessons learned and recommendations for similar collaborative initiatives.

The interviews yielded qualitative insights into the experiences and perspectives of the educators who facilitated the tandem course. Educators emphasized the value of international collaboration. “My motivation was stimulated because of the topic and the opportunity to collaborate with an international team, discover shared passions, and explore different approaches.” The course helped them build confidence in using gamification. “It made me even more convinced that it’s a great way of teaching.” Working with colleagues from diverse backgrounds enhanced their skills. “This experience shaped my professional identity, with visibility in my academic community for international teaching collaborations.” Time constraints and virtual collaboration were challenging, but teamwork made success possible. “Time management was challenging, but all the pressure finally allowed us to create a very creative and innovative tandem course.” Educators started using gamification more often, improving their lessons. “The course transformed my teaching style, making it more engaging and student-centered.”

The interviews revealed how collaborative course design can foster motivation, professional growth, and innovative teaching practices. Educators highlighted the benefits of international teamwork, the confidence gained in applying gamification, and the transformation of their teaching styles toward more student-centered approaches. The findings also revealed practical insights into overcoming challenges, like time constraints and virtual collaboration, through strong teamwork and adaptability.

All seven educators say the co-design sessions were “energizing”, “creatively intense”, or “the best PD this year”. This means that interactive, tandem work itself is a playful mechanic that keeps teachers in a state of flow. Every teacher reports a net gain in willingness to embed game elements after the project. Designing with rather than for peers triggers ownership and intrinsic motivation. Sentences like “I now feel equipped to defend gamification to skeptical colleagues” are expressed by six of seven respondents. Shared experimentation plus peer feedback reduces the perceived risk of trying novel methods. Several teachers noticed “visible curiosity spikes” and “more cameras on” when they piloted the prototype tasks with their own classes. Early, low-stakes trials give immediate positive reinforcement, further fueling motivation. Barriers have a rather logistical nature: time zones, institutional red tape, uneven digital skill levels, while pedagogical alignment within the team was largely unproblematic.

Key findings from the interviews can therefore be summarized as follows:

- Collaboration with international colleagues fostered inspiration and diverse perspectives.

- Educators expanded their skills and adopted new strategies through interdisciplinary teamwork.

- Strong teamwork helped educators navigate challenges and achieve successful outcomes.

- The course encouraged more engaging and student-focused teaching practices.

6. Summary

Recent research on teacher collaboration in higher education, particularly through creative and digital partnerships, suggests that networking and innovative approaches in teaching and learning significantly enhance both teacher and student engagement and motivation (Zainuddin et al., 2020; Abegglen et al., 2023).

The tandem course on gamification and game-based learning provided a valuable collaborative space for educators, emphasizing the role of teacher motivation in fostering engaging classroom environments. These findings align with those reported by other higher education institutions across Europe and Asia, where the integration of gamification and co-teaching strategies has notably improved teacher training outcomes and strengthened resilience in digitally mediated pedagogical environments (Fonseca et al., 2023; D. Wang et al., 2021). This experience demonstrated a promising increase in motivation among participants, who shared strategies, resources, and peer support to develop interactive, student-centered teaching methods. While these preliminary findings suggest that such collaborative frameworks can positively influence teacher motivation and classroom engagement, further research is needed to assess the long-term impact of these methods. Future studies should explore how sustained motivation among educators might influence classroom dynamics and student outcomes over time, and whether structured collaborative opportunities like tandem courses could serve as a viable approach to enhancing educational practices on a broader scale.

This study is an initial investigation that contributes to developing the new literature on teacher motivation and collaborative learning models. It will serve as a foundation for future, more extensive research on the role of gamification and teacher collaboration in evolving pedagogical practices to meet contemporary educational needs. This can be a starting point for more in-depth exploration of specific game mechanics or long-term impacts of game-based learning on skill retention, as well as using tandem courses on a wider and more interdisciplinary scale.

Author Contributions

The contributions of all authors to this research are acknowledged as equal, with responsibilities shared in the areas of conceptualization, data collection, analysis, and manuscript preparation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research only involved anonymous questionnaire responses analysis without collecting any personal data (such as names, emails, or identifying information), and questions were non-sensitive. Participants were only adults and were informed about the purpose of the questionnaire. It was to know their opinion about the tandem course and have feedback about organizers’ and participants’ involvement.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all our participants for providing us with invaluable input and feedback. Furthermore, we would like to thank our colleagues from the FORTHEM Alliance for their support and cooperation. Appreciation is extended to reviewers, whose feedback and insights were instrumental in improving the quality of the paper. Gratitude is also expressed to the institutions and individuals who supported the completion of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abegglen, S., Burns, T., & Sinfield, S. (2023). Collaboration in higher education. A new ecology of practice. Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Almazova, N. I., Rubtsova, A., Eremin, Y., Kats, N., & Baeva, I. (2020). Tandem language learning as a tool for international students sociocultural adaptation. In Integrating engineering education and humanities for global intercultural perspectives (pp. 174–187). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Antala, B., Tománek, Ľ., Cihová, I., Balga, T., Dovicak, M., & Polakovič, R. (2023). Health and movement, physical and sports education and tandem teaching in the curricular reform in Slovack primary schools. Fiep Bulletin Online, 93(1), 270–275. Available online: https://ojs.fiepbulletin.net/fiepbulletin/article/view/6629 (accessed on 30 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Appel, C., & Mullen, T. (2000). Pedagogical considerations for a web-based tandem language. Computer & Education, 34(3–4), 291–308. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0360131599000512 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Arnold, M., North, B., Fischer, H., Mueller, J., & Diab, M. (2021, March 8–9). Game-based learning in vet schools: A learning architecture for educators in vocational education. 15th International Technology, Education and Development Conference (pp. 3297–3303), Online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arufe, G. V., Sanmiguel-Rodríguez, A., Ramos Álvarez, O., & Navarro-Patón, R. (2022a). Can gamification influence the academic performance of students? Sustainability, 4(9), 5115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arufe, G. V., Sanmiguel-Rodríguez, A., Ramos-Álvarez, O., & Navarro-Patón, R. (2022b). Gamification in physical education: A systematic review. Education Sciences, 12(8), 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizan, I. D., Alias, M., & Mustafa, M. Z. (2021). Effect of game-based learning in vehicle air-conditioning course on cognitive and affective skills of vocational students. Journal of Technical Education and Training, 13(3), 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbie, E. (2008). Podstawy badań społecznych. PWN. [Google Scholar]

- Banfield, J., & Wilkerson, B. (2014). Increasing student intrinsic motivation and self-efficacy through gamification pedagogy. Contemporary Issues in Education Research, 7(4), 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batardière, M.-T., & Jeanneau, C. (2020). Towards developing tandem learning in formal language education. Learning and Teaching Languages and Cultures in Tandem, 39(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruen, J., & Sudhershan, A. (2015). “So they’re actually real?” integrating E-Tandem learning into the study of language for international business. Journal of Teaching in International Business, 26(2), 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, F. J. (2000). Team teaching: What, why, and how? Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F., Chen, L., Tseng, C., Pai, C. H., Tsai, K., Liang, E., Chen, Y., Chen, T., Liu, S., Lee, P., Lai, K., Liu, B. R., Fouad, K. E., & Chen, C. (2025). Enhancing student engagement and learning outcomes in life sciences: Implementing interactive learning environments and flipped classroom models. Discover Education, 4(1), 102. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s44217-025-00501-x (accessed on 30 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., & Liang, M. (2022). Play hard, study hard? The influence of gamification on students’ study engagement. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 994700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopoulos, A., & Mystakidis, S. (2023). Gamification in education. Encyclopedia, 3(4), 1223–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahalan, F., Alias, N., & Shaharom, M. S. N. (2024). Gamification and game based learning for vocational education and training: A systematic literature review. Education and Information Technolgies, 29, 1279–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, I., Caviedes, M., Chantré, J., & Bernate, J. (2023). Gamification and game-based learning as cooperative learning tools: A systematic review. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 18(21), 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero Puerta, L. (2024). Exploring if gamification experiences make an impact on pre-service teachers’ perceptions of future gamification use: A case report. Societies, 14(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P., & Goyal, P. (2022). Is game-based pedagogy just a fad? A self-determination theory approach to gamification in higher education. International Journal of Educational Management, 36(3), 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansell, K., Pörn, M., & Bäck, S. (2021). Teachers’ interaction in combined physical and virtual learning environments: A case study of tandem language learning and teaching in Finland. Apples—Journal of Applied Language Studies, 15(2), 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanus, M. D., & Fox, J. (2015). Assessing the effects of gamification in the classroom: A longitudinal study on intrinsic motivation, social comparison, satisfaction, effort, and academic performance. Computers & Education, 80, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.-T. (2023). Diverse development and future challenges of game-based learning and gamified teaching research. Education Sciences, 13(4), 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, E. (2024). Dual language tandem teaching: Coordinating instruction across languages through cross-linguistic pedagogies. Velazquez Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jayasinghe, U., & Dharmaratne, A. (2013, August 26–29). Game-based learning vs. gamification from the higher education students’ perspective. 2013 IEEE International Conference on Teaching, Assessment and Learning for Engineering (pp. 683–688), Bali, Indonesia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, A. (2023). A service-learning program for multilingual education at an early age: Tandem teaching experiences. In J. L. E. Chichón, & F. Z. Martínez (Eds.), Handbook of research on training teachers for bilingual education in primary schools (pp. 186–207). IGI Global. Available online: https://www.igi-global.com/chapter/a-service-learning-program-for-multilingual-education-at-an-early-age/318362 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Kapp, K. M. (2012). The gamification of learning and instruction: Game based methods and strategies for training and education (R. Taff, Ed.). Pfeiffer. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S., Song, K., Lockee, B., & Burton, J. (2018). What is gamification in learning and education? In Gamification in learning and education (pp. 25–38). Springer. Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-47283-6 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Krath, J., Schürmann, L., & von Korflesch, H. F. (2021). Revealing the theoretical basis of gamification: A systematic review and analysis of theory in research on gamification, serious games and game-based learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 125, 106963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krompák, E., & Hartmann, E. (2023). Multimodal literacy and linguistic landscape: A digital tandem project in european teacher education—Littéracie multimodale et paysage linguistique—Un projet de tandem numérique pour la formation des enseignants européens. Enseignement et Apprentissage des Langues et Éducation à la Citoyenneté Numérique, 26(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laanemaa, E., Hatšaturjan, A., Kibar, T., Piirsalu, S., Kuzmina, O., & Sõrmus, E. (2023, November 9–10). The experience of using tandem language learning in professional higher education. Innovation in Language Learning International Conference, Florence, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Lampropoulos, G., & Sidiropoulos, A. (2024). Impact of gamification on students’ learning outcomes and academic performance: A longitudinal study comparing online, traditional, and gamified learning. Education Sciences, 14(4), 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X., Lu, B., & Khumsat, T. (2024). Ideas for the construction of Chinese-Thai e-Tandem course with the aim of creating a target language environment. Journal of Sinology, 18(1), 230–249. Available online: https://journals.mfu.ac.th/jsino/article/view/128 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Man, C. K. (2021). Game elements, components, mechanics and dynamics: What are they? Creative Culture. Available online: https://medium.com/creative-culture-my/game-elements-components-mechanics-and-dynamics-what-are-they-80c0e64d6164 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Manzano-León, A., Camacho-Lazarraga, P., Guerrero, M. A., Guerrero-Puerta, L., Aguilar-Parra, J. M., Trigueros, R., & Alias, A. (2021). Between level up and game over: A systematic literature review of gamification in education. Sustainability, 13(4), 2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikrouli, P., Tzafilkou, K., & Protogeros, N. (2024). Applications and learning outcomes of game-based learning in education. International Educational Review, 2(1), 25–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R. P., de Souza, C. G., Reis, A. d. C., & de Souza, W. M. (2021). Gamification in e-learning and sustainability: A theoretical framework. Sustainability, 13(21), 11945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, B. (2005). Form-focused Interaction in Online Tandem Learning. CALICO Journal, 22(3), 433–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porshneva, E. R., Markey, D., Abdulmianova, I. R., & Lebedeva, M. V. (2020). Teaching and learning in tandem: The dialogue of cultures in practice. Available online: https://www.europeanproceedings.com/article/10.15405/epsbs.2020.11.03.81 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Prieto-Andreu, J. M., Gómez-Escalonilla-Torrijos, J. D., & Said-Hung, E. (2022). Gamification, motivation, and performance in education: A systematic review. Revista Electrónica Educare, 26, 251–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, S. H., Ansari, A. B., & Ahmad, F. A. (2024). Gamification and game-based learning: Future of education. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research, 10(5), 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rap, A., Hopfgartner, F., Hamari, J., Linehan, C., & Cena, F. (2019). Strengthening gamification studies: Current trends and future opportunities of gamification research. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 127, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, K., Plangger, K., Kietzmann, J. H., McCarthy, I., & Pitt, L. (2015). Is it all a game? Understanding the principles of gamification. Business Horizons, 58, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodt, S., & Ryklief, Y. (2019). Using digital game-based learning to improve the academic efficiency of vocational education students. International Journal of Game-Based Learning, 9(4), 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R., & Zaman, B. (2018). Need-supporting gamification in education: An assessment of motivational effects over time. Computers & Education, 127, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutledge, C., Walsh, C. M. M., Swinger, N., Auerbach, M. M., Castro, D. D., Dewan, M., Khattab, M., Rake, A., Harwayne-Gidansky, I., Raymond, T. T., Maa, T., & Chang, T. P. M. (2018). Gamification in action: Theoretical and practical considerations for medical educators. Academic Medicine, 93(7), 1014–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schug, D., & Torea, T. (2023). International E-tandems: A tool for increasing student motivation in the foreign language classroom. Arab World English Journal, (1), 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swacha, J. (2021). State of research on gamification in education: A bibliometric survey. Education Sciences, 11(2), 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szyszka, M., Smirnov, I., & Benchetrit, R. (2018). Towards crossing the borders in foreign language teacher training: A report on a pilot phase of the Tandem Learning for Teacher Training project. Border and Regional Studies, 6(4), 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šķiltere, D. (2015). Biznesa imitācijas spēles. Attīstīsim uzņēmējspējas! (176p) GlobeEdit, OmniScriptum GmbH & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Tateo, L., Machado Dazzani, M. V., He, M., & Stadskleiv, K. (2024). The research-tandem model as student-led training to international research. In M. V. Machado Dazzani, K. Stadskleiv, M. He, & L. Tateo (Eds.), Research-based international student involvement. cultural psychology of education (vol. 17). Springer. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-78837-6_1 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Vázquez-Vílchez, M., Garrido-Rosales, D., Pérez-Fernández, B., & Fernández-Oliveras, A. (2021). Using a cooperative educational game to promote pro-environmental engagement in future teachers. Education Sciences, 11(11), 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinagre, M. (2007). Integrating tandem learning in higher education. In Online Intercultural Change. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voogt, J., Laferrière, T., Breuleux, A., Itow, R. C., Hickey, D. T., & McKenney, S. (2015). Collaborative design as a form of professional development. Instructional Science, 43(2), 259–282. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11251-014-9340-7 (accessed on 30 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., Khambari, M. N. M., Wong, S. L., & Razali, A. B. (2021). Exploring interest formation in English learning through XploreRAFE+: A gamified AR mobile app. Sustainability, 13(22), 12792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., Chen, N., Li, J., & Sun, G. (2021). SNS use leads to luxury brand consumption: Evidence from China. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 38(1), 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werbach, K., & Hunter, D. (2012). For the win: How game thinking can revolutionize your business. In For the win, revised and updated edition. Wharton Digital Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C. J. (2012). Tandem learning. In N. M. Seel (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the sciences of learning. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainuddin, Z., Chu, S. K. W., Shujahat, M., & Perera, C. J. (2020). The impact of gamification on learning and instruction: A systematic review of empirical evidence. Educational Research Review, 30, 100326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeivots, S., Hopwood, N., Wardak, D., & Cram, A. (2024). Co-design practice in higher education: Practice theory insights into collaborative curriculum development. Higher Education Research & Development, 44(3), 769–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).