Maria Montessori’s Educational Approach to Intellectual Disability and Autism: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

Purpose of This Review

2. Materials and Methods

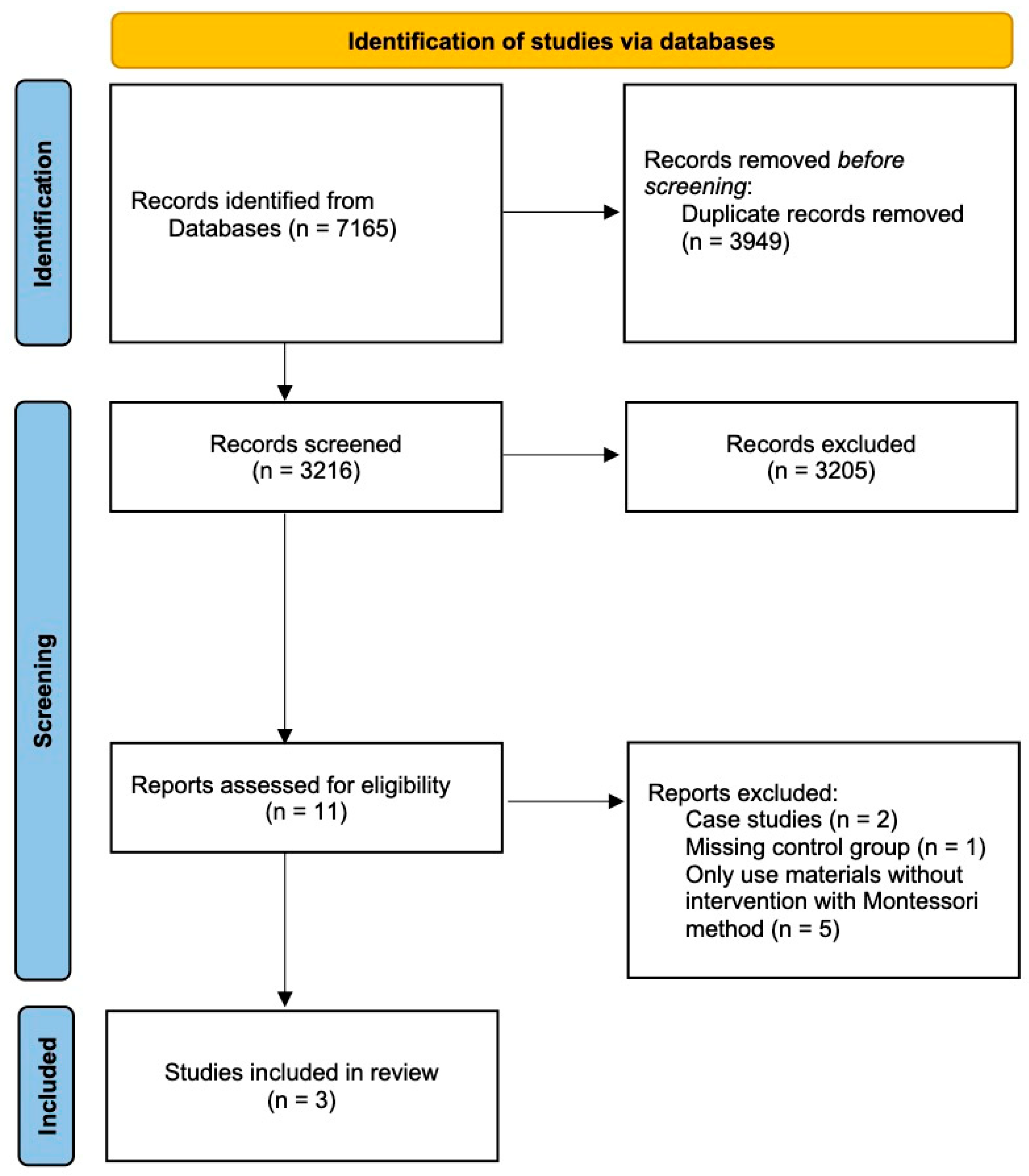

2.1. Study Design and Search Strategy

2.2. Selection Criteria

2.3. Selection Procedures, Screening and Data Elaboration

3. Data Synthesis

4. Results

Summary of Studies

5. Discussion

6. Implications for Clinical Practice and Research

7. Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ackerman, D. J. (2019). The Montessori preschool landscape in the United States: History, programmatic inputs, availability, and effects. ETS Research Report Series, 2019, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshan, A., Mushtaq, A., Rehna, T., Sabih, F., & Najmussaqib, A. (2024). Effectiveness of Montessori sensorial training program for children with mild intellectual disabilities in Pakistan: A randomized control trial. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 71(1), 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babini, V. P. (1996). La questione dei frenastenici. Alle origini della psicologia scientifica in Italia (1870–1910) [The question of frenasthenics. The origins of scientific psychology in Italy (1870–1910)]. Franco Angeli. [Google Scholar]

- Beccaluva, E., Riccardi, F., Gianotti, M., Barbieri, J., & Garzotto, F. (2022). VIC-A tangible user interface to train memory skills in children with intellectual disability. International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction, 32, 100376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollea, G. (1998). Maria Montessori e il bambino handicappato [Maria Montessori and the disabled child]. Psichiatria dell’Infanzia e dell’Adolescenza, 65, 517–522. [Google Scholar]

- Caprara, B., & Macchia, V. (2019). La visione del bambino in Maria Montessori: Tra pedagogia speciale, psicologia dello sviluppo e didattica generale [Maria Montessori’s vision of the child: Between special education, developmental psychology, and general didactics]. Italian Journal of Special Education for Inclusion, 7(2), 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demangeon, A., Claudel-Valentin, S., Aubry, A., & Tazouti, Y. (2023). A meta-analysis of the effects of Montessori education on five fields of development and learning in preschool and school-age children. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 73, 102182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denervaud, S., Fornari, E., Yang, X. F., Hagmann, P., Immordino-Yang, M. H., & Sander, D. (2020). An fMRI study of error monitoring in Montessori and traditionally-schooled children. NPJ Science of Learning, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denervaud, S., Knebel, J.-F., Hagmann, P., & Gentaz, E. (2019). Beyond executive functions, creativity skills benefit academic outcomes: Insights from Montessori education. PLoS ONE, 14(11), e0225319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Serio, B. (2013). Il metodo Montessori e le case dei bambini. Un modello educativo per liberare l’infanzia e avviarla alla conquista dell’indipendenza. Tabanque: Revista Pedagógica, 26, 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, A., & Lee, K. (2011). Interventions shown to aid executive function development in children 4 to 12 years old. Science, 333, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Nunes, E. P., da Conceição Júnior, V. A., Giraldelli Santos, L. V., Pereira, M. F. L., & de Faria Borges, L. C. (2017). Inclusive toys for rehabilitation of children with disability: A systematic review. In Universal access in human–computer interaction. Design and development approaches and methods: 11th international conference, UAHCI 2017, held as part of HCI international 2017, Vancouver, BC, Canada, July 9–14, 2017, Proceedings, Part I 11 (pp. 503–514). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, P. E., Fornari, E., Décaillet, M., Ledoux, J.-B., Beaty, R. E., & Denervaud, S. (2023). Creative thinking and brain network development in schoolchildren. Developmental Science, 26, e13389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, A., Lindeman, N., & Polychronis, S. (2020). Montessori: A promising practice for young learners with autism spectrum disorder. Montessori Life, 31(4), 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Gallelli, R. (2008). La didattica di Maria Montessori e la ricerca neuroscientifica contemporanea [Maria Montessori’s teaching methods and contemporary neuroscientific research]. Pedagogia più Didattica, 1, 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, T., Bai, J. Y. H., Keevy, M., & Podlesnik, C. A. (2018). Resurgence when challenging alternative behavior with progressive ratios in children and pigeons. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 110, 474–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwanowski, P. S., Stengel-Rutkowski, S., Anderlik, L., Pilch, J., & Midro, A. T. (2005). Physical and developmental phenotype analyses in a boy with Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome. Genetic Counseling, 16(1), 31–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kaya, E. Ö., & Torun, S. (2022). Analyzing the selected Eurofit test batteries of the children with Down syndrome and autism in the age range of 12–16 and receiving Montessori education. African Educational Research Journal, 10(4), 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, M., & Yildiz, K. (2019). The effect of Montessori programme on the motion and visual perception skills of trainable mentally retarded individuals. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 7(2), 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keevy, M., Bai, J. Y., Ritchey, C. M., & Podlesnik, C. A. (2022). Examining combinations of stimulus and contingency changes with children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder and pigeons. Learning and Motivation, 78, 101806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimball, R. T., Greer, B. D., Randall, K. R., & Briggs, A. M. (2020). Investigations of operant ABA renewal during differential reinforcement. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 113, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kıran, I., Macun, B., Argın, Y., & Ulutaş, İ. (2021). Montessori method in early childhood education: A systematic review. Cukurova University Faculty of Education Journal, 50(2), 1154–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’Ecuyer, C., Bernacer, J., & Güell, F. (2020). Four pillars of the Montessori method and their support by current neuroscience. Mind, Brain, and Education, 14(4), 322–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. (2025). Global autism prevalence, and exploring Montessori as a practical educational solution: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 16, 1604937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X., Li, R., Wong, S. H., Sum, R. K., Wang, P., Yang, B., & Sit, C. H. (2022). The effects of exercise interventions on executive functions in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 52, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liggett, A. P., Nastri, R., & Podlesnik, C. A. (2018). Assessing the combined effects of resurgence and reinstatement in children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 109, 408–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lillard, A. S. (2012). Preschool children’s development in classic Montessori, supplemented Montessori, and conventional programs. Journal of School Psychology, 50(3), 379–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillard, A. S. (2016). Montessori: The science behind the genius (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lillard, A. S., & Else-Quest, N. (2006). The early years: Evaluating Montessori education. Science, 313(5795), 1893–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillard, A. S., Jiang, R. H., & Tong, X. (2025). Perfect timing: Sensitive periods for Montessori education and long-term wellbeing. Frontiers in Developmental Psychology, 3, 1546451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, A. H., Forman, L., Brown, R., & Frances, A. (1994). A brief history of psychiatric classification. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 17, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, L. (2016). Playing to learn: An overview of the Montessori Approach with pre-school children with autism spectrum condition. Supporting for Learning, 31(4), 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, C. (2017). Montessori education: A review of the evidence base. NPJ Science of Learning, 2(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molineri, G. C., & Alesio, G. C. (Eds.). (1899, September 8–15). T. Atti del “Primo congresso pedagogico nazionale Italiano”. Proceedings of the “First Italian National Pedagogical Congress, Torino, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Montessori, M. (1902, ). Norme per una classificazione dei deficienti in rapporto ai metodi speciali di educazione [Standards for classifying mentally disabled individuals in relation to special education methods]. II° Congresso Pedagogico Nazionale, Napoli, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Montessori, M. (1916). L’autoeducazione nelle scuole Elementari. Continuazione del Volume II: Metodi della Pedagogia scientifica applicato all‘educazione infantile nelle Case dei Bambini [Self-education in elementary schools. Continuation of Volume II: Scientific pedagogical methods applied to early childhood education in Children’s Houses]. Loescher. [Google Scholar]

- Montessori, M. (1970). La scoperta del bambino [The discovery of the child]. Garzanti. [Google Scholar]

- Petretto, D. R., Mura, A., Carrogu, G. P., Gaviano, L., Atzori, R., & Vacca, M. (2025). “What is in a name?”—Definition of mental disorder in the last 50 years: A scoping review, according to the perspective of clinical psychology. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1545341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, J. S. (1992). Successful applications of Montessori methods with children at risk for learning disabilities. Annals of Dyslexia, 42, 90–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randolph, J. J., Bryson, A., Menon, L., Henderson, D. K., Kureethara, M. A., Michaels, S., Rosenstein, D. L. W., McPherson, W., O’Grady, R., & Lillard, A. S. (2023). Montessori education’s impact on academic and nonacademic outcomes: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 19, e1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosati, N. (2021). Montessori method and universal design for learning: Two methodologies in conjunction for inclusive early childhood education. Ricerche di Pedagogia e Didattica—Journal of Theories and Research in Education, 16(2), 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D. H., & Gravel, J. W. (2010). Universal design for learning. In P. Peterson, E. Baker, & B. McGraw (Eds.), International encyclopedia of education (pp. 119–124). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Sablić, M., Mirosavljević, A., & Bogatić, K. (2025). Multigrade education and the Montessori model: A pathway towards inclusion and equity. International Journal of Educational Research, 131, 102600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarimski, K. (1999). Early development of children with Williams syndrome. Genetic Counseling, 10(2), 141–150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schalock, R. L., Luckasson, R., & Tassé, M. J. (2021). An overview of intellectual disability: Definition, diagnosis, classification, and systems of supports. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 126(6), 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, C. L., McArthur, C., & Hitzig, S. L. (2016). A systematic review of Montessori-based activities for persons with dementia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 17(2), 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shvarts, S., Jimenez-Gomez, C., Bai, J. Y. H., Thomas, R. R., Oskam, J. J., & Podlesnik, C. A. (2020). Examining stimuli paired with alternative reinforcement to mitigate resurgence in children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder and pigeons. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 113, 214–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafolla, M., Singer, H., & Lord, C. (2025). Autism spectrum disorder across the lifespan. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 21, 193–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tīģere, I., Bethere, D., Jurs, P., & Ļubkina, V. (2025). Developing Inclusive preschool education for children with autism applying universal learning design strategy. Education Sciences, 15(6), 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornar, C. (1982). I materiali strutturati montessoriani: Una “riscoperta”. Psicologia e Scuola, 10, 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Venturi, C. (2023). Prospettive attuali del Montessori nella scuola primaria. In T. Pironi (Ed.), Maria Montessori tra passato e presente. La diffusione della sua pedagogia in Italia e all’estero [Maria Montessori between past and present. The spread of her pedagogy in Italy and abroad] (pp. 209–224). Franco Angeli. [Google Scholar]

- Winarni, T. I., Schneider, A., Borodyanskara, M., & Hagerman, R. J. (2012). Early intervention combined with targeted treatment promotes cognitive and behavioral improvements in young children with fragile x syndrome. Case Reports in Genetic, 2012, 280813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.-L., Lin, T.-J., Chiou, G.-L., Lee, C.-Y., Luan, H., Tsai, M.-J., Potvin, P., & Tsai, C.-C. (2021). A systematic review of MRI neuroimaging for education research. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 617599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanchi, P., Mullier, E., Fornari, E., Guerrier de Dumast, P. M., Alemán-Gómez, Y., Ledoux, J.-B., Beaty, R., Hagmann, P., & Denervaud, S. (2024). Differences in spatiotemporal brain network dynamics of Montessori and traditionally schooled students. NPJ Science of Learning, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuckerman, O., Arida, S., & Resnick, M. (2005, April 2–7). Extending tangible interfaces for education: Digital Montessori inspired manipulatives. CHI ’05: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 859–868), Portland, OR, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | N | Chronological Age M (S.D.) Years | Intervention Characteristics/Materials/Study Design | Reason for Exclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Ho et al., 2018) | N = 5 children, 3 boys, 2 girls with ASD | Range 3–8 years | Montessori object permanence boxes | Only use of materials without intervention with Montessori method |

| (Liggett et al., 2018) | N = 3 children, 2 boys, 1 girl with ASD | Range 2–8 years | Montessori object permanence box | Only use of materials without intervention with Montessori method |

| (Kimball et al., 2020) | N = 10 children with ASD, 1 language delay, 1 neurotypical | Range 2–8 years | Montessori object permanence boxes | Only use of materials without intervention with Montessori method |

| (Shvarts et al., 2020) | N = 5 children with ASD | Range 2–8 years | Montessori object permanence boxes | Only use of materials without intervention with Montessori method |

| (Keevy et al., 2022) | N = 3 children with ASD | Range 6–8 years | Montessori object permanence boxes | Only use of materials without intervention with Montessori method |

| (Sarimski, 1999) | N = 10 children, 5 boys and 5 girls, Williams syndrome | Range 1–6 years | Play sessions following the Montessori approach | Missing control group |

| (Winarni et al., 2012) | N = 1 boy and 1 girl fragile-X syndrome | Range 3–7 years | Program with elements of Montessori homeschooling | Case studies |

| (Iwanowski et al., 2005) | N = 1 boy with Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome | 1–10/12-year-old | Interactive play sessions according to Montessori principles | Case study |

| References | N | Chronological Age M (S.D.) Years | Country | Context | IQ | Intervention Characteristics | Outcome Measures | Study Design | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (M. Kaya & Yildiz, 2019) | N = 24 men with ID (N = 12 control group, N = 12 experimental group) | Range 20–22 years | Turkey | Private School | - | Sensorial materials; daily life materials; mothers’ support intervention (8 week formation) | Movement test (standing broad jump tests; medicine ball throw test; flexibility measurement; handgrip strength measurement; 20 m sprint test; standing stork test—blind); perception test (evaluating visual perception skills) | Random cluster sampling method | Improvement in visual perception skills, except the shape–ground connection, and in movement skills |

| (E. Ö. Kaya & Torun, 2022) | N = 20 boys with ID (N = 10 control group, 5 Down syndrome, 5 ASD; N = 10 experimental group, 5 Down syndrome, 5 ASD) | Range 12–16 years | Turkey | Special education and rehabilitation centers | - | Montessori education materials | Eurofit test batteries (height and body weight measurements; flamingo balance test; plate tapping test; sit and reach test; standing long jump test; handgrip test) | Random cluster sampling method | Improvement in physical activities and some motor skills according to the results of plate tapping, standing long jump, and sit and reach tests |

| (Afshan et al., 2024) | N = 30 (43.3%) girls with ID (N = 15 control group, N = 15 experimental group) | M = 10.01 (2.84) Range 6–13 years | Pakistan | Special education school | 50–70 | Sensorial materials; 2 sessions (each session 50–60 min); 1 expert, and 3 special teachers | Cognitive Abilities Checklist; Adaptive Function Assessment Form | Randomized control trial | Improvement in cognitive abilities, communication, and self-care domain |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Di Blasi, F.D.; Costanzo, A.A.; Stimoli, M.A.; Liccardi, G.; Zoccolotti, P.; Buono, S. Maria Montessori’s Educational Approach to Intellectual Disability and Autism: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Research. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1031. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081031

Di Blasi FD, Costanzo AA, Stimoli MA, Liccardi G, Zoccolotti P, Buono S. Maria Montessori’s Educational Approach to Intellectual Disability and Autism: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Research. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1031. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081031

Chicago/Turabian StyleDi Blasi, Francesco Domenico, Angela Antonia Costanzo, Maria Agatina Stimoli, Giuseppa Liccardi, Pierluigi Zoccolotti, and Serafino Buono. 2025. "Maria Montessori’s Educational Approach to Intellectual Disability and Autism: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Research" Education Sciences 15, no. 8: 1031. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081031

APA StyleDi Blasi, F. D., Costanzo, A. A., Stimoli, M. A., Liccardi, G., Zoccolotti, P., & Buono, S. (2025). Maria Montessori’s Educational Approach to Intellectual Disability and Autism: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Research. Education Sciences, 15(8), 1031. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081031