Abstract

European Researchers’ Night 2023 was developed at the National Museum of Natural History and Science of Lisbon, Portugal, with the motto “Science for Everyone (SCIEVER)—Inclusion and Sustainability”. The event promotes the relevance of science and research by focusing on the social, economic, and environmental dimensions of sustainability and inclusion and bridging the gap between scientists, students, and civil society. Our study aims to understand the impact of the event on 30 students from a degree in Basic Education, who completed a questionnaire before and after the event. Data collection was focused on the audience’s expectations and engagement with the activities and the perceived value of such events. The students attended the event as a group, and the individual experiences described were similar: the importance of the European Researchers’ Night in raising awareness of science in initial teacher training. The findings may have implications in terms of curricula revision, education research, and education policies.

1. Introduction

European Researchers’ Night as a Stage for STEM Learning

In a world decisively influenced by scientific development, science communication holds growing relevance in enabling informed decision-making and the participation of citizens in society and political discourse (Humm & Schrögel, 2020). Thus, opportunities to learn about, engage with, question, and critique science have become increasingly important in contemporary societies. In this context, the European Researchers’ Night (ERN) initiative contributes to such scientific awareness.

Starting in 2005, as an initiative of the European Commission action (funded by the Horizon 2020 program in the form of Marie Skłodowska-Curie Action grants), ERN attracts more than one million visitors each year, all over Europe. This event occurs on the evening and night of the last Friday of September, and in 2023, the ERN took place in 26 European countries, including Portugal. The overall aim of the initiative is to “bring research and researchers closer to the public; promote excellent research projects across Europe and beyond; increase the interest of young people in science and research careers; and showcase the impact of researchers’ work on people’s daily lives” (European Commission, 2023).

One of the ERN’s key aspects is that it takes place across a multitude of designed settings and experiences outside of the formal classroom (Allen & Peterman, 2019), in so-called non-formal and informal science education, understood as something that can happen in non-formal venues, implying the learning of structured, mediated specific contents, or informally, depending on individual experiences and choices (Clapham & Barata, 2024). Another aspect is that ERN is an example of an initiative that fosters the development of STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics) skills and demonstrates the practical relevance of their education. STEM education aims to integrate those disciplines by establishing connections between real-life problems, which need a multi-disciplinary resolution (Bozkurt Altan & Ercan, 2016). This teaching approach is crucial for ensuring that children and young people have the necessary skills, knowledge, and mindset to be responsible and active citizens (European Commission, 2022), with implications for national development and productivity, economic competitiveness, and societal well-being (Marginson et al., 2013; Freeman et al., 2019; Montgomery & Fernández-Cárdenas, 2018). Thus, STEM education may play an important role within Initial Teacher Education (ITE) in contributing to active citizenship and societal well-being. As Dawson (2014) notes, teacher training in science education is important to equip people with the tools, skills, and information to negotiate contemporary life or enter scientific professions. In this sense, it is also crucial that future teachers have contact with environments like the ERN by providing an awareness of the relationship between science and society, which a school-based science learning environment could not assure (Jarvis & Pell, 2005). This contact is relevant when, despite the emphasis on numeric and scientific literacy in the European Education Area, the share of pupils not reaching basic achievement levels remains considerably above the agreed maximum of 15% (European Commission, 2022). In the case of Portugal, over 10 years (between 2012 and 2022), mathematical literacy fell by 14.6%, that of reading fell by 12.8%, and that of science fell by 7.3% (OECD, 2023). To improve these results, it is important to develop integrated education programs capitalizing on the knowledge and skills of every discipline (Roberts, 2012). Additionally, training STEM teachers (Bozkurt Altan & Ercan, 2016), changing the structure of education programs (see Sengupta et al., 2019), and recruiting researchers to increase students’ awareness of the relevance of science learning (Sahin, 2015) are essential steps. It is also important that policies in ITE—for preschool, basic, and upper secondary education—stimulate teacher development throughout the continuum approach and recognize formal, non-formal, and informal learning as valid and powerful means of professional development (European Commission, 2015).

Students’ contact with science in non-formal or informal environments (e.g., science festivals, museums, botanical gardens, and natural parks) has shown various benefits by providing opportunities to engage with science in inspiring, relevant, and educational ways (Canovan, 2019; Phipps, 2010). This contact facilitates learning by making abstract concepts more concrete, contributing to the development of affective characteristics such as interest, attitude, and motivation, and contributing to the creation of learning environments where students are researching, questioning, and responsible for their own learning, and where the teacher can focus on guiding and directing—which is too often taken for granted as a basis for science curriculums in more formal settings (Yildirim, 2018). In terms of cognitive learning, Whitesell (2016) found that attending a non-formal or informal science education institution had a small positive effect on students’ science performance. On the other hand, other studies showed a positive attitude toward science, through increased interest, motivation, and skills development (Lin & Schunn, 2016; Sontay et al., 2016; Bakioglu, 2017; Yildirim, 2018; Susperreguy et al., 2020). Furthermore, out-of-school learning environments can be more effective in supporting formal learning (Karademir, 2013; Taylor & Caldarelli, 2004) by being more natural, flexible, and entertaining than school education (Noel, 2007).

As Bultitude (2014) explains, modern science festivals are an opportunity for engaging more diverse audiences than is possible through many other forms of science engagement, and they provide a burst of focused effort, resulting in a much higher impact than is possible through a series of unconnected individual events.

The ERN 2023 project coordinated by the National Museum of Natural History and Science (MUHNAC) in Lisbon, Portugal, had two main goals: (i) to raise Portuguese citizens’ awareness, particularly young people, toward innovation and research conducted in Europe to promote (social, economic, and environmental) sustainability and inclusion while preserving ecosystems and natural resources, and (ii) to bring researchers closer to civil society and students, enabling meaningful opportunities for communities to express concerns and expectations about how research and science address climate change and promote sustainable growth.

This study is part of a broader experimental project aimed at evaluating the impact of engaging students from a Basic Education degree in science projects as a valid and powerful method for fostering their professional development. Similarly, it also aims to help students develop the knowledge, skills, and attitudes that promote ways of thinking, planning, and acting with empathy, responsibility, and care for our planet, within the framework of the GreenComp, the European Sustainability Competence Framework (Bianchi et al., 2022). We explore the 2023 ERN at Lisbon as a means to (i) counter the lack of published research available about the ERN, despite the high number of events (Boyette & Ramsey, 2019; Roche et al., 2018; Jensen et al., 2021), and (ii) gather data on public perceptions and awareness regarding the range of scientific activities that demonstrate informal learning at the ERN and assess the potential for integrating these activities into formal educational contexts (during degree classes or in future pedagogical settings). This objective follows the trend of policies that aim to stimulate teacher training throughout the continuum approach and recognize formal, non-formal, and informal learning as valid and powerful means of professional development (European Commission, 2015). Considering the above, our study addresses the following research question to measure the educational impact of the initiative: What are the participants’ opinions and expectations about the ERN before and after participating in the event?

2. Methodology

2.1. ERN at MUHNAC—University of Lisbon

“Science for everyone (SCIEVER)—sustainability and inclusion” was the title of the ERN action (Call: SEP-210792697), covering the years 2022–2023 and four cities across Portugal (Lisbon, Braga, Coimbra, and Évora). The SCIEVER consortium, coordinated by the University of Lisbon through the National Museum of Natural History and Science (MUHNAC-ULisbon), combined the efforts of a number of researchers from Portuguese universities, building on experience from previous successful ERN actions in which the output was carefully evaluated. Lessons learned translated into greater clarity of the ERN’s impacts, including the event’s COVID-19-driven online transition. Given the previous positive results, the consortium proposed a digital program both as an alternative and as a complement to the main program. The event was free and well-publicized to the community (e.g., TV, radio, newspapers, maps, flags, newsletters, website, and social media) and was also made fully inclusive, in line with current recommendations.

The ERN 2023 in Lisbon took place on the 29th of September at MUHNAC-ULisbon between 5 p.m. and 12 a.m.; it hosted 500 researchers from 88 scientific institutions, developing 162 activities in STEAM education with the motto “Inclusion and Sustainability” (Architecture, Arts and Design, Human and Social Sciences, Environmental and Natural Sciences, Physics, and Chemistry, Technology, Mathematics, Health Sciences, and interactive performances). The event brought together a wide range of science shows for the audiences (e.g., science tours, interviews, debates, speed dates, science exhibits, remote labs, public lectures, workshops, meet-the-researchers, roundtables, hands-on activities, games, quizzes, science theatres, competitions, digital activities, astronomical observation, live demonstrations, interactive performances, and sports). The on-site event brought together 4100 people, participating in activities inside of MUHNAC-ULisbon and outside, at the Lisbon Botanical Garden and at the Príncipe Real Garden, a historical public garden. The event relied heavily on the museum staff and volunteer staff (e.g., university students and members of the general public), as in other science festivals (Jensen & Buckley, 2011).

2.2. Context

This study was conducted within the context of a science curricular unit, focusing on a case study of teacher training in STEAM education. Given the 2023 ERN subtheme “Inclusion and Sustainability”, the intervention aimed to determine the opinion and expectations of a group of university students about using the Lisbon ERN event to design pedagogical itineraries that support theoretical content and develop active educational methodologies aligned with sustainable objectives. It was assumed that some educational strategies about sustainability may align closely with the ERN activities, where researchers demonstrate scientific subjects. These activities promote hands-on learning, increasing students’ engagement in science in a fun way. Such strategies aim to foster critical and creative thinking, as well as problem-solving skills required in 21st-century society. This relationship was also found through the application of the survey before and after the pedagogical intervention at the ERN event, aimed at the development of sustainability competencies for education intervention (Cohen et al., 2018).

The study sample included a group of university students from a degree in Basic Education (n = 30, pre-visit and n = 25 post-visit from the same group), aged eighteen to forty-five years old, of both sexes (2 males and 28 females), from the Jean Piaget Higher School of Education, in Almada, Portugal (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characterization of the sample of classes of the Basic Education Course from the Jean Piaget School of Education.

For the type of area where respondents reside (Q4), 66.7% lived in urban areas, 30% lived in peri-urban areas, and the rest lived in rural areas (3.3%). The most frequent level of education (Q5) was higher education students, with 53.3% of respondents, followed by 5 respondents with a degree, 3 with a master’s (10%), and 2 with secondary education (6.7%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characterization of respondents (pre-visit questionnaire).

The sample is classified as intentional because it was chosen at the discretion of the researchers (Pardal & Correia, 1995) as a case study. The class was selected considering the objectives and theme of the ERN 2023, the student’s curricula, and the fact that the degree in Basic Education from the Piaget Institute is directly related to the mission, tradition, and training experience of the institution, which trains educators and teachers for the use of active educational strategies about relevant themes for society, like inclusion and sustainability. The degree gives access to postgraduate studies under the respective legal terms, namely, access to Preschool Education; Teaching in Primary Education; Preschool Education and Teaching in Primary Education; Teaching in Primary Education and teaching Portuguese, History, and Geography of Portugal in Middle Education; and Teaching Primary Education and Mathematics and Natural Sciences in Middle Education. These different postgraduate degrees enable students to practice teaching in the respective areas and levels of education.

2.3. Data Collection

The data were collected between 20 September (pre-visit questionnaire) and 20 October (post-visit questionnaire), among the same sample, by using a Google Forms questionnaire via email, before and after their participation in the activities of the Lisbon 2023 ERN event. The online questionnaire was a fast, economical, and efficient solution, simplifying the data recording process and reducing the chance of error, as noted in other studies (Solomon, 2001; Jansen et al., 2007). To ensure the credibility of the questionnaire, in addition to the filling time estimated between 10 and 15 min, the following criteria were implemented: (i) being clear as a whole; (ii) covering all topics to be included; (iii) presenting the most appropriate questions; (iv) asking questions to obtain the type of information needed to answer the research problem; and (v) requesting empirical data.

2.4. Data Analysis

The study employed a mixed methodology for data collection through questionnaire surveys, combining quantitative analysis for frequency results of yes/no questions with qualitative analysis for the open-ended questions. Both before and after surveys included a mix of closed-ended questions (e.g., demographic data and yes/no questions) and open-ended questions (e.g., “Indicate the name of the three activities that you most enjoyed participating in?” and “What do you think about “scientific research?”) to gather a more comprehensive set of data. Previous studies have demonstrated the reliability of this combination (Bogner & Wiseman, 2004). The analysis of the open questions followed a process of coding the answers using the content analysis method (Pardal & Correia, 1995)—given the small sample, coding and categorization were directly performed by the researchers. This methodology has proven useful in the analysis of other scientific studies (Yilmaz et al., 2013). Proximity categorization was chosen as a methodological approach to identify emerging patterns in the responses. As Babbie (2015) argues, this process facilitates the study of social events without being obtrusive and can efficiently handle large amounts of data, making it both effective and accessible. To ensure intercoder reliability of the data, we engaged three researchers outside the ERN team. Working with a heterogeneous group of researchers—experts in the fields of Education Science, Psychology, Biology, and Science Communication—reinforced the validation of the questionnaire and helped to define the size and scope of the questions to be asked.

Therefore, at the beginning of September 2023, a study with a sample of 5 randomly selected students was conducted to test the reliability of the preliminary research instruments. These procedures allowed the researchers to assess the objectivity of the questions, eliminate confusing or redundant questions, and estimate the duration, leading to the final version of the questionnaire. Other studies have shown the effectiveness of this methodology (Coutinho, 2011).

Besides the five demographic questions, the pre-questionnaire included ten questions about interest in scientific areas and events, opinions on scientific research, participation in previous ERN events and opinions, interest and expectations about participating in the 2023 ERN Lisbon event, the relevance of such an event to professional training, and how to adapt the ERN contents or activities to professional practice.

The post-questionnaire integrated thirteen questions about satisfaction with participation in the 2023 ERN Lisbon event, the number and scientific area of the activities chosen within the event, the main goal of the ERN event, satisfaction about interaction with researchers, understanding of the activity goals, favorite types of activities, and the ranking of the three best and worst activities, followed by three positive and three negative aspects of the event as a whole, and finally, the intention to participate again and defining the event in just one word.

No prior information on the research topic was disclosed to the participants. Informed consent for participation was obtained from all participants involved. Participants were informed about the study’s objectives, the project’s host institution, data confidentiality, and the estimated time to complete the questionnaire. All data were collected confidentially and anonymously, in compliance with the European Data Protection Regulation. Participants were informed that they could withdraw their consent at any time without any penalty.

The quantitative analysis of close yes/no questions allowed for the calculation of frequencies that would complement the qualitative results given by the content analysis of open questions. All the respondents consented for the anonymized data to be used for research (including academic publication).

3. Results

From the 30 students who filled in the pre-visit questionnaire, only 25 answered the post-visit questionnaire: two students dropped out of the course, and three were sick.

3.1. Pre-Visit Questionnaire

Interest in scientific issues (Q6) had a positive score, including 83.3% of respondents, with 70% saying that they were interested in participating in scientific events. These results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Interest in scientific issues (pre-visit questionnaire).

The content analysis of the question “What do you think about scientific research?” (Q7) identified five qualitative categories. Knowledge was the most used to define “scientific research” (Table 4). Some responses had elements grouped into more than one category because the answer reflected several ideas, reflecting the rich data set.

Table 4.

Representative examples of excerpts from the answers given and emerging categories from the question “What do you think about scientific research?” (Q7) (pre-visit questionnaire).

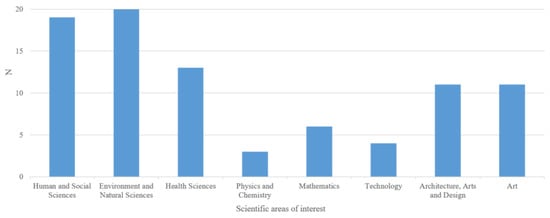

Exploring the topic “interest in scientific area” (Q8), the most significant scientific areas were Environmental and Natural Sciences (69% of respondents) and Social and Human Sciences (65.5%), with similar numbers. These were followed by Health Sciences (44.8%), Architecture and Design (37.9%), Arts (37.9%), Mathematics (20.7%), Technologies (13.8%), and Physical Chemistry (10.3%). The results are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Bar chart of the scientific area of interest (pre-visit questionnaire).

In the question “Are you interested in participating in scientific events?” (Q9), 70% of respondents said yes and 30% say no. Most respondents were unaware of the existence of the ERN in Portugal (86.7%), and none had participated in a previous edition (Q11), but 86.7% responded positively when asked about their interest in participating in the ERN (Q12). Respondents who replied positively to Q12 were asked the open question “What do you expect to find at the European Researchers’ Night?” (Q12.1). From the content analysis, three concepts emerged and were useful for grouping participants’ answers (Table 5).

Table 5.

Representative examples of excerpts from the answers given and emerging categories from question 13.1 “What do you expect to find at the European Researchers’ Night?” (pre-visit questionnaire).

From the two participants who did not show an interest in participating (Q12.2), one said “I don’t know” and the other said “I don’t know the event, so I have no motivation”. Of note, 86.7% respondents thought that participation in this type of event is essential for their professional training (Q13) and also think about framing the activities developed in their pedagogical practice (Q14) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Frequency table of questions related to scientific events (pre-visit questionnaire).

We also conducted a content analysis of the answers to the question “If you said yes, indicate in what way” (Q14.1) following the question “Do you plan to adapt the activities carried out at the European Researchers’ Night into your pedagogical/professional practice?” (Q14). Four qualitative categories were identified, highlighting participants’ interest in collecting ideas and adapting them to the classroom, with 10 occurrences (Table 7). The two participants who answered “No” simply answered “I don’t know”.

Table 7.

Representative examples of excerpts from the answers given and emerging categories from the question “If you said yes, indicate in what way” (Q14.1) following the question “Do you plan to adapt the activities carried out at the European Researchers’ Night into your pedagogical/professional practice?” (Q14) (pre-visit questionnaire).

3.2. Post-Visit Questionnaire

Regarding satisfaction with participating in the ERN 2023 event (Q6), 96% said yes (Table 8). The reasons (Q6.1) emerge from the content analysis conducted, where the diversity of innovative and dynamic projects and the interesting set of activities appear as the most referenced (Table 9). To the question “How many activities did you participate” (Q7), 64% participated in fewer than 10 activities, and 28% participated in between 11 and 20. Of note, 92% of respondents reported having enjoyed the interaction with the researchers (Q10), with 60% stating that the objectives of the activities were clear and 36% stating only sometimes (Q11). About the three modalities in which they most liked to participate (Q12), 48% of the respondents answered games, 40% answered conversations and demonstrations, and 8% answered guided visits and exhibitions (Table 8).

Table 8.

Frequency table of question Q8, related to scientific events (post-visit questionnaire).

Table 9.

Representative examples of excerpts from the answers given and emerging categories from question 6.1 “Did you enjoy participating in the ERN? Why?” (post-visit questionnaire).

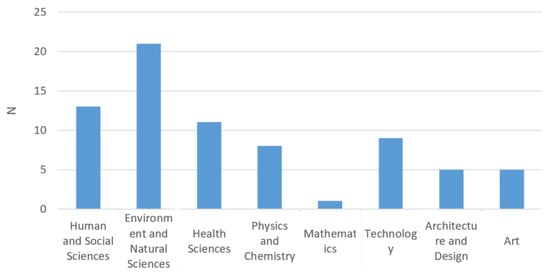

In terms of which “scientific areas” were most frequently mentioned (Q8), once again, Environmental and Natural Sciences received the most positive responses (84%), followed by Social and Human Sciences (52%), Health Sciences (44%), Technologies (36%), Physical Chemistry (32%), Arts (20%), Architecture and Design (20%), and finally, Mathematics (4%) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Bar chart of the scientific area of interest (post-visit questionnaire).

From the content analysis of the question “What was the objective of the ERN?” (Q9), four categories emerged: learn, projects/scientific institutions, science and society, and others. The participants focused on learning science subjects in a practical, playful, and pedagogical way but also recognized that the event presented projects and publicized scientific institutions. Four respondents said that the objective was to bring society closer to science (Table 10).

Table 10.

Representative examples of excerpts from the answers given and emerging categories from the question “What was the objective of the ERN?” (Q9) (post-visit questionnaire).

From the content analysis of the question “What are the three activities you enjoy the most?” (Q13), four coding categories emerged, scientific areas (35), session types (7), all activities (2), and other (1), which manifests the perception of the scientific area by the participants. The most mentioned activities were astronomy and virtual reality (Table 11).

Table 11.

Representative examples of excerpts from the answers given and emerging categories from the question “What are the three activities you enjoy the most?” (Q13) (post-visit questionnaire).

The three activities most disliked by participants (Q14) were the human genome, insects, and math activities (Table 12). The scientific areas of most interest were Environmental and Natural Sciences, Social and Human Sciences, and Environmental Science and Health. The areas generating the least interest were Arts, Design, and finally, Mathematics.

Table 12.

Representative examples of excerpts from the answers given and emerging categories from question 14, “What are the three activities you dislike most?” (post-visit questionnaire).

From the content analysis of the question “Point out three aspects that went well” (Q15), six categories emerged: activities (18), public communications (13), organization (13), local (3), staff (3), and others (4) (Table 13).

Table 13.

Representative examples of excerpts from the answers given and emerging categories from question 15, “Point out three aspects that went well” (post-visit questionnaire).

From the content analysis of question Q16, “Point out three aspects that went wrong”, five categories emerged: Nothing (11), Explanation (10), Space (2), Schedule (2), and Others (4) (Table 14).

Table 14.

Representative examples of excerpts from the answers given and emerging categories from question 16, “Point out three aspects that went wrong” (post-visit questionnaire).

Of note, 72.0% of respondents stated that they would like to participate in upcoming ERN events (Q17), with 20% saying that they were not interested in participating and 8% stating maybe (see Table 15).

Table 15.

Frequency table of question 17, related to future participation in ERN (post-visit questionnaire).

Based on the content analysis of question Q18, “Define ERN 2023 in a single word,” the top three most frequently occurring words are interesting, knowledge, and innovative. All of these words align well with the goals of the ERN and the goals of educational training (Table 16).

Table 16.

The top three most frequently occurring words from question 18, “Define ERN 2023 in a single word” (post-visit questionnaire).

4. Discussion

We acknowledge that the sample size, with only 25 participants in the post-test and a 16% loss from the pre-test, limits the generalizability of our results. This limitation may affect the external validity of the study since the representativeness of the sample is reduced. However, due to practical and logistical constraints, it was necessary to work with this specific sample, which we considered a case study. Additionally, complementary qualitative analyses can provide a deeper understanding of the data and strengthen the study’s conclusions.

Proximity-based categorization was an initial methodological choice to identify emerging content patterns in responses. However, we recognize the importance of deepening the analysis and are committed to incorporating additional techniques, such as the use of specialized software and the verification of inter-coder agreement, to enhance the rigor and validity of the research.

The marked numerical discrepancy between male and female students participating in this study is supported by previous research, such as the study published by the University of Madeira (Portugal). This study revealed that in 2018–2019, there was a significant numerical disparity between male and female students enrolled in teacher training courses for early childhood education, with 107 women and only 3 men (Mendonça et al., 2019). This demonstrates the female predominance in early childhood education professions (educators and primary school teachers).

In this study, we focus on university students’ opinions and expectations about participating in scientific events, such as the ERN. Based on the findings presented herein, we show that the students’ participation in the ERN was a valuable opportunity to interact with scientific projects. The range of topics mentioned by the respondents helps to address the research question: “What are the participants’ opinions and expectations about the European Researchers’ Night before and after the event?”. Although most respondents were interested in science, they were not aware of the existence of the ERN, and none of the respondents had previously attended, or intended to attend, an ERN event. For most participants in the study, this may have reinforced their motivation for participating in the event. Our results suggest that more communication about the ERN is needed to counter higher education students’ lack of awareness and information about the event. This is consistent with other studies that refer to the importance of participatory communication models as becoming a broader goal of public engagement events (Bultitude et al., 2011), even while research institutions continue to struggle to reach out beyond their enthusiastic supporters and that these science festivals are falling short of their aims to make science accessible to a broad audience (Jensen et al., 2021; Kennedy et al., 2018; Von Roten & Moeschler, 2007).

Despite this low awareness about scientific events, most of the participants understood the objectives of the ERN and described them as simple and clear and were positive regarding their interest in participating in further scientific events. This is also aligned with the results of Owen et al. (2013) and Kennedy et al. (2018). The participants’ expectations about participating in the ERN were centered around curiosity about new areas of scientific knowledge and experiencing the evolution of human knowledge, as shown in previous studies (Jensen & Buckley, 2014; Jensen et al., 2021). Other expectations were related to fun and exciting experiences and innovation, mostly related to Environmental and Natural Sciences. Therefore, according to the Greencomp (Bianchi et al., 2022), the participation of these students in the ERN activities under the themes of “Inclusion and Sustainability” seems to have fostered an interest in sustainability and the promotion of an inquiry mindset by engaging them in activities that may promote new skills for creative thinking in the search for solutions to societal problems. As expected, they preferred scientific projects in which the interaction with the researchers was more effective and with future application in a pedagogical context. The sample population of participants in the event is students completing a degree in Basic Education; therefore, it is not representative of the general public.

Most of the students also believe that participation in this type of event is essential for teacher training and for framing the activities developed in the pedagogical activity. Other studies about science festival audiences refer to the necessity of achieving true, socially inclusive quality public engagement (Belin, 2018; Jensen & Roche, 2019; Jensen et al., 2021; Kennedy et al., 2018). The school or, in the particular case of this study, the higher education institution, plays a crucial role in democratizing education by offering scientific experiences to students. These institutions serve as important places where students can access knowledge and opportunities that help counteract the inequalities they might face at home. By providing such experiences, schools and universities help to create a higher training level, ensuring that all students have the chance to grow academically and personally. As demonstrated by Canovan (2019), most families may see science as ‘narrow’ and ‘not for us’. This study showed that attendance at science festivals improved the perception of science, and families were significantly more likely to feel increased positivity about their children pursuing science careers. Other studies also corroborate these findings by showing that the representation of groups such as women and those from more deprived backgrounds remains stubbornly low, particularly in the physical sciences (Nunes et al., 2017; Henderson et al., 2017). As Humm and Schrögel (2020, p. 2) have said, “What is known, is that science communication only reaches certain parts of society”. Therefore, including scientific events in teacher training brings science closer to students and may empower them to create new ways of teaching toward an inquiry-based methodology to engage the learners.

The participants enjoyed the event for a variety of reasons mentioned: notably the diversity of innovative and dynamic projects, but also direct interaction with STEM researchers. The results highlight the importance given by the participants during the ERN to hands-on practical activities. Participants mentioned games, conversations and demonstrations, guided visits, and exhibitions as something they enjoyed. It seems that the direct involvement between participants and researchers is also crucial and has been identified in previous research as a key factor in achieving participant impacts (see Chen, 2014; Jensen & Buckley, 2014; Bultitude & Sardo, 2012; Sardo & Grand, 2016; Wiehe, 2014). Other studies also report a desire for fun or inspiring encounters and feel that attending science festivals provides that opportunity (see Craig et al., 2011; Jensen, 2012; Jensen & Buckley, 2011; Sardo & Grand, 2016). We agree with Falk and Dierking (2012), who consider that understanding factors that may contribute to participant enjoyment of scientific events is important because participants are more likely to return and tell others about the event if they feel satisfied with the experience, ensuring a rise in future attendance numbers.

To the question “Do you plan to adapt the activities carried out at the European Researchers’ Night into your pedagogical/professional practice?”, the results indicated that students acquired new knowledge they did not have before and that they were aware of the potential of the event for developing new pedagogical activities, in particular dynamic activities, that could support knowledge acquisition about everyday concepts in future pedagogical contexts. The students were well attuned to the pedagogical potential of the ERN. We considered that these findings provide a crude approximation that the ERN itself is functioning as a non-formal and informal learning event, as Roche et al. (2018) also note. These observations are in line with the guidelines of the Teaching and Learning International Survey—Talis (OECD, 2014), which considers that, in school, informal and non-formal learning activities that are team-based and directly related to the daily work context are the most prominent and most efficient and effective ways of learning. This awareness is important because if these students become future teachers, it is important that they develop scientific activities with children from the earliest years. As several studies have shown, children’s attitudes begin to be shaped from an early age, and the school period plays an important role in the development of positive attitudes toward science (see Melber & Brown, 2008; Parker & Gerber, 2000).

5. Conclusions

This paper has helped to explore the perceptions of university students enrolled in a Basic Education degree about the relevance of scientific events for teacher training, in particular the ERN. Data collection focused on their expectations, engagement with the activities, and perceived value of these events. The students attended the ERN as a group, and the individual experiences were quite similar: they recognized the event’s importance in raising awareness about science within initial teacher education. The study demonstrates that participants are satisfied and motivated to engage in science activities. They are enthusiastic about experiencing and playing with science in the future, as well as becoming more aware of its relevance to their pedagogical practice. Additionally, the research highlights the role of the ERN in increasing students’ awareness of science’s importance. Participating in the ERN provided a practical and enriching experience that complements the theoretical content. By promoting hands-on activities that interpret everyday phenomena, the event shows how students can understand these concepts in a simple, accessible, and even fun way, illustrating the real impact of science in daily life. The results also emphasize the importance of democratizing access to science, fostering a reciprocal relationship where science becomes more accessible to the community, and vice versa. The student’s participation in the ERN was crucial in encouraging them to learn about STEM fields and helping them feel more comfortable with these topics. Furthermore, it underscores the importance of aligning learning objectives with effective teaching methods and the Sustainable Development Goals, promoting quality and sustainable education. As future teachers, this experience could serve as an opportunity to promote similar initiatives with their students, helping to present science as a fun and inspiring subject. Overall, this study aims to contribute to addressing the limited research on science festivals like the ERN. Future research with larger and more diverse samples is recommended to validate these findings and improve their generalization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.P.L.; methodology, R.P.L.; software, R.P.L.; validation R.P.L., J.M.A.F., S.T., C.d.S., and R.B.; formal analysis, R.P.L., J.M.A.F., S.T.; investigation, R.P.L.; resources, R.P.L.; data curation, R.P.L.; writing—original draft preparation, R.P.L.; writing—review and editing, R.P.L., J.M.A.F., S.T., C.d.S., and R.B.; visualization, R.P.L., J.M.A.F., S.T., C.d.S., and R.B.; supervision, R.P.L.; funding acquisition, R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

European Commission action (Call: SEP-210792697). Raquel Pires Lopes was financially supported by a Post-Doctoral Research Scholarship (BIPD), funded by the European Union through the Marie Sklodowska-Curie actions program, under the of the project “European Researchers’ Night 2022-23–101061524-SCIEVER”, with the reference 04/BIPD/2022. João Ferreira was financially supported by a Research Scholarship (BI), funded by the European Union through the Marie Sklodowska-Curie actions program, under the of the project “European Researchers’ Night 2022-23–101061524-SCIEVER”, with the reference 02/BI/2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the fact that in Portugal, the collection of data through questionnaires is governed by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the national law that ensures its implementation, Law No. 58/2019. This regulation applies to all countries in the European Union and establishes strict guidelines on how personal data should be handled, including obtaining informed consent. In this study, informed consent for participation was obtained from all participants involved. Participants were informed about the study’s objectives, data confidentiality, and the estimated time to complete the questionnaire. All data were collected confidentially and anonymously, in compliance with the European Data Protection Regulation. Participants were informed that they could withdraw their consent at any time without any penalty. This information was also presented at the beginning of the questionnaire given to the students.

Informed Consent Statement

The need for participant consent was waived due to the fact that in Portugal, the collection of data through questionnaires is governed by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the national law that ensures its implementation, Law No. 58/2019. This regulation applies to all countries in the European Union and establishes strict guidelines on how personal data should be handled, including obtaining informed consent. In this study, informed consent for participation was obtained from all participants involved. Participants were informed about the study’s objectives, data confidentiality, and the estimated time to complete the questionnaire. All data were collected confidentially and anonymously, in compliance with the European Data Protection Regulation. Participants were informed that they could withdraw their consent at any time without any penalty. This information was also presented at the beginning of the questionnaire given to the students.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the European Commission for funding. They are also very grateful to all the participants who agreed to collaborate in this study by completing the questionnaires and consenting to the use of their answers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Allen, S., & Peterman, K. (2019). Evaluating informal STEM education: Issues and challenges in context. In A. C. Fu, A. Kannan, & R. J. Shavelson (Eds.), Evaluation in informal science, technology, engineering, and mathematics education. New directions for evaluation (vol. 161, pp. 17–33). Wiley Periodicals, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Babbie, E. R. (2015). The practice of social research. Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Bakioglu, B. (2017). Effectiveness of out-of-school learning setting aided teaching of the 5th grade let’s solve the riddle of our body chapter [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Amasya University Institute of Science.

- Belin, C. (2018). Formal Learning in an informal setting: The cognitive and affective impacts of visiting a science center during a school field trip [Ph.D. thesis, University of Arkansas]. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, G., Pisiotis, U., & Cabrera, M. (2022). GreenComp: The european sustainability competence framework (Y. Punie, & M. Bacigalupo, Eds.). EUR 30955 EN; JRC128040. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogner, F. X., & Wiseman, M. (2004). Outdoor ecology education and pupils’ environmental perception in preservation and utilization. Science Education International, 15(1), 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Boyette, T., & Ramsey, J. R. (2019). Does the messenger matter? Studying the impacts of scientists and engineers interacting with public audiences at science festival events. Journal of Science Communication, 18(2), A02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt Altan, E., & Ercan, S. (2016). STEM education program for science teachers: Perceptions and competencies. Journal of Turkish Science Education, 13, 103–117. [Google Scholar]

- Bultitude, K. (2014). Science festivals: Do they succeed in reaching beyond the ‘already engaged’?”. JCOM, 13(04), C01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bultitude, K., McDonald, D., & Custead, S. (2011). The rise and rise of science festivals: An international review of organised events to celebrate science. International Journal of Science Education, Part B, 1(2), 165–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bultitude, K., & Sardo, M. (2012). Leisure and pleasure: Science events in unusual locations. International Journal of Science Education, 34(18), 2775–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canovan, C. (2019). Going to these events truly opens your eyes. Perceptions of science and science careers following a family visit to a science festival. Journal of Science Communication, 18(02), A01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G. (2014). National science festival of Thailand: Historical roots, current activities and future plans of the national science Fair. Journal of Science Communication, 13(4), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapham, A., & Barata, R. (2024). Fighting the machine: Co-constructing team based evaluation for non-formal learning. Museum & Society, 22(2), 29–47. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (8th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, C. P. (2011). Metodologia de Investigação em ciências sociais e humanas. Edições Almedina. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, E., O’Brien, B., Youngs, R., Visscher, N., Morrissey, K., & Owen, K. (2011). Visitor expectations and satisfaction at Burke museum family day events. Evaluation Report. CAISE Center for Advancement of Informal Science Education. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, E. (2014). Equity in informal science education: Developing an access and equity framework for science museums and science centers. Studies in Science Education, 50(2), 209–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2015). Schools policy education & training 2020. Shaping career-long perspectives on teaching. A guide on policies to improve initial teacher education. Available online: https://wikis.ec.europa.eu/download/attachments/44165762/Shaping%20career-long%20perspectives%20on%20teaching.pdf?version=2&modificationDate=1683218225261&api=v2 (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- European Commission. (2022). EACEA—Increasing achievement and motivation in mathematics and science learning in schools. Eurydice report. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. (2023). Commission staff working document. Accompanying the document proposal for a council recommendation on pathways to school success (Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture Ed.). DGEC—European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, J. H., & Dierking, L. D. (2012). Lifelong learning for adults: The role of free-choice experiences. In B. Fraser, K. Tobin, & C. J. McRobbie (Eds.), Second international handbook of science education (pp. 1063–1079). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, B., Marginson, S., & Tytler, R. (2019). An international view of STEM education. In STEM education 2.0. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, M., Sullivan, A., Anders, J., & Moulton, V. (2017). Social class, gender and ethnic differences in subjects taken at age 14. The Curriculum Journal, 29(3), 298–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humm, C., & Schrögel, P. (2020). Science for all? Practical recommendations on reaching underserved audiences. Frontiers in Communication, 5, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, K. J., Corley, K. G., & Jansen, B. J. (2007). E-survey methodology. In R. A. Reynolds, R. Woods, & J. D. Baker (Eds.), Handbook of research on electronic surveys and measurements (pp. 1–8). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, T., & Pell, A. (2005). Factors influencing elementary school children’s attitudes toward science before, during, and after a visit to the UK National Space Centre. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 42(1), 53–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, A. M., Jensen, E. A., Duca, E., & Roche, J. (2021). Investigating diversity in European audiences for public engagement with research: Who attends European researchers’ night in Ireland, the UK and Malta? PLoS ONE, 16(7), e0252854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, A. M., & Roche, J. (2019). Section 5: Science communication in museums within Europe. In S. R. Davies (Ed.), Summary report: European science communication today, deliverable 1.1 (pp. 51–68). Wiley Periodicals, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, E. (2012). External evaluation report: Science in Norwich Day. University of Warwick. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Eric_Jensen4/publication/267779286_External_Evaluation_Science_in_Norwich_Day_External_Evaluation_Report_Science_in_Norwich_Day/links/554798450cf26a7bf4d99698.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Jensen, E., & Buckley, N. (2011). The role of university student volunteers in festival-based public engagement. National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, E., & Buckley, N. (2014). Why people attend science festivals: Interests, motivations and selfreported benefits of public engagement with research. Public Understanding of Science, 23(5), 557–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karademir, E. (2013). Determination of objectives realization at outdoor science education activities of teachers and pre-service teachers by the theory of planned behavior within the scope of science and technology lesson [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Hacettepe University Institute of Social Sciences.

- Kennedy, E. B., Jensen, E. A., & Verbeke, M. (2018). Preaching to the scientifically converted: Evaluating inclusivity in science festival audiences. International Journal of Science Education, Part B, 8(1), 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P. Y., & Schunn, C. (2016). The dimensions and impact of informal science learning experiences on middle schoolers’ attitudes and abilities in science. International Journal of Science Education, 38(17), 2551–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marginson, S., Tytler, R., Freeman, B., & Roberts, K. (2013). STEM: Country comparisons: International comparisons of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) education. Final report. Australian Council of Learned Academies. [Google Scholar]

- Melber, L. M., & Brown, K. D. (2008). Not like a regular science class: Informal science education for students with disabilities. A Journal of Educational Strategies, 82(1), 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, A., Brazão, J., Nascimento, A., & Freitas, D. (2019). Estereótipos de género entre os estudantes da formação de professores em educação infantil (0–10 anos): Estudo de caso na Universidade da Madeira. Ensaios Pedagógicos, 3, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, C., & Fernández-Cárdenas, J. (2018). Teaching STEM education through dialogue and transformative learning: Global significance and local interactions in Mexico and the UK. Journal of Education for Teaching, 44(1), 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, A. M. (2007). Elements of a winning field trip. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 44(1), 42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, T., Bryant, P., Strand, S., Hillier, J., Barros, R., & Miller-Friedmann, J. (2017). Review of SES and science learning in formal educational settings. Available online: https://royalsociety.org/-/media/policy/topics/education-skills/education-research/evidence-review-eef-royalsociety-22-09-2017.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- OECD. (2014). TALIS 2013 results. An international perspective on teaching and learning. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2023). PISA 2022 results (volume I): The state of learning and equity in education. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, R., Stilgoe, J., Macnaghten, P., Gorman, M., Fisher, E., & Guston, D. (2013). A framework for responsible innovation. In Responsible innovation: Managing the responsible emergence of science and innovation in society (vol. 31, pp. 27–50). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Pardal, L., & Correia, E. (1995). Métodos e técnicas de investigação social. Areal Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, V., & Gerber, B. L. (2000). Effects of a science intervention program on middle-grade student achievement and attitudes. School Science and Mathematics, 100, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, M. (2010). Research trends and findings from a decade (1997–2007) of research on informal science education and free-choice science learning. Visitor Studies, 13(1), 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A. (2012). A justification for STEM education. Technology and Engineering Teacher, 71(8), 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Roche, J., Davis, N., Chaikovsky, M., Boyle, S. O., & Farrelly, C. O. (2018). European researchers night as a learning environment. The International Journal of Interdisciplinary Educational Studies, 13(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, A. (2015). STEM students on the stage (SOS): Promoting student voice and choice in STEM education through an interdisciplinary, standards-focused project based learning approach. Journal of STEM Education, 16(3), 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Sardo, A. M., & Grand, A. (2016). Science in culture: Audiences’ perspective on engaging with science at a summer festival. Science Communication, 38(2), 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, P., Shanahan, M. C., & Kim, B. (2019). Critical, transdisciplinary and embodied approaches in STEM education. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, D. J. (2001). Conducting web-based surveys. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 7(1), 19. [Google Scholar]

- Sontay, G., Tutar, M., & Karamustafaoglu, O. (2016). Student views about “science teaching with outdoor learning environments”: Planetarium tour. Journal of Research in Informal Environments, 1(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Susperreguy, M. I., Di Lonardo Burr, S., Xu, C., Douglas, H., & LeFevre, J. (2020). Children’s home numeracy environment predicts growth of their early mathematical skills in kindergarten. Child Development, 91(5), 1663–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, E. W., & Caldarelli, M. (2004). Teaching beliefs of non-formal environmental educators: A perspective from state and local parks in the United States. Environmental Education Research, 10(4), 451–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Roten, F. C., & Moeschler, O. (2007). Is art a “good” mediator in a science festival? Journal of Science Communication, 6(3), A02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitesell, E. R. (2016). A day at the museum: The impact of field trips on middle school science achievement. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 53(7), 1036–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiehe, B. (2014). When science makes us who we are: Known and speculative impacts of science festivals. Journal of Science Communication, 13(04), C02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, H. (2018). The impact of out-of-school learning environments on 6th grade secondary school students attitude towards science course. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 6(12), 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, S., Timur, S., & Timur, B. (2013). Secondary school students’ key concepts and drawings about the concept of environment. Anthropologist, 16(1–2), 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).