“It’s Like a Nice Atmosphere”—Understanding Physics Students’ Experiences of a Flipped Classroom Through the Lens of Transactional Distance Theory

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Transactional Distance

Transactional distance is the extent to which the teacher manages to successfully engage the students in their learning. If students are disengaged and not stimulated into being active learners, there can be a vast transactional distance, whether the students are under the teacher’s nose or on the other side of the city. But if a teacher, whether online or on campus, can establish meaningful educational opportunities, with the right degree of challenge and relevance, and can give students a feeling of responsibility for their own learning and a commitment to this process, then the transactional gap shrinks and no one feels remote from each other or from the source of learning.(p. 6)

2.1. Structure

2.2. Dialogue

2.3. Autonomy

3. Large Classes

4. Flipped Classroom

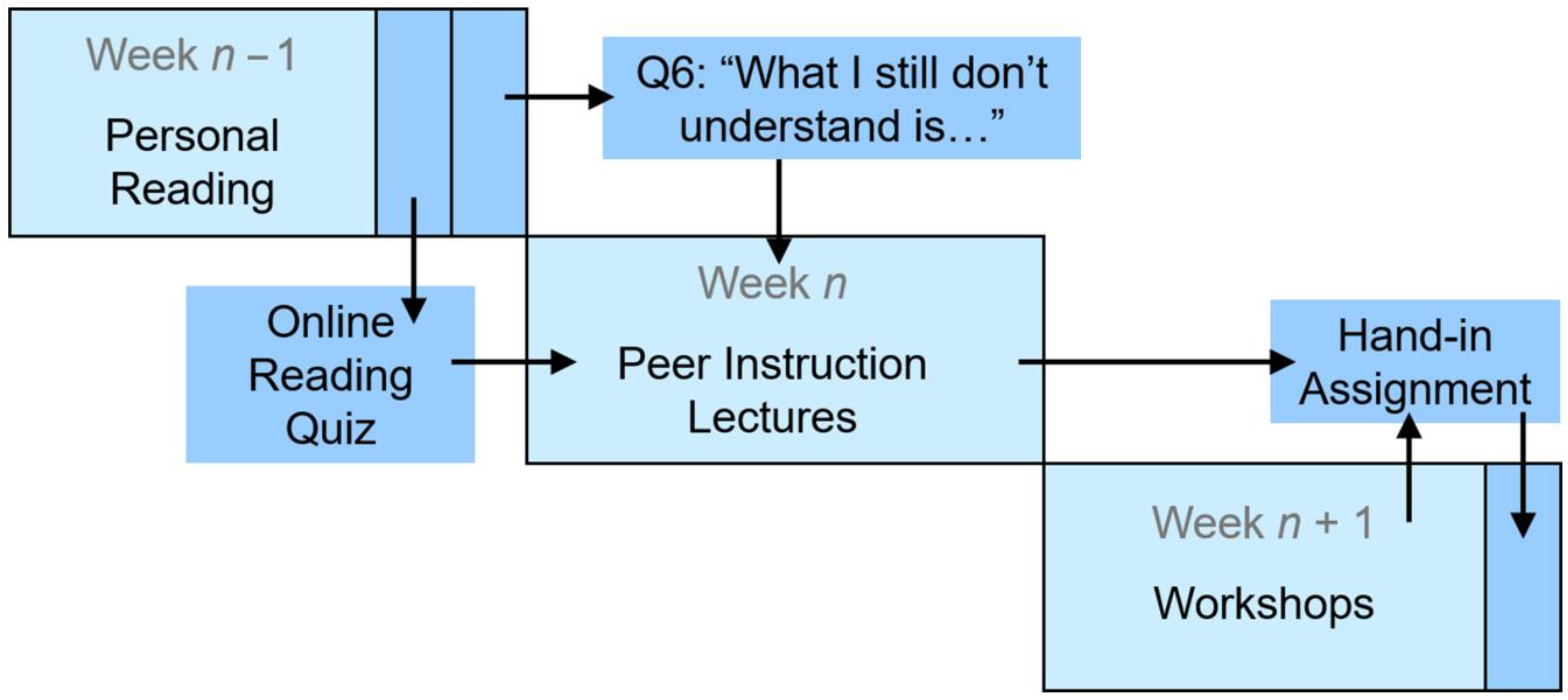

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Context

5.2. Data Collection

5.3. Data Analysis

6. Results

6.1. Creating Connections

‘When the audience is engaged with the lecturer, there is a sense of community that everyone is understanding and there are more people who would want you to ask those questions’.[Student A]

and being able to think along with everyone else at the same pace, that feels quite nice cause also, I mean, obviously everyone has this experience at least once in University where you sorta feel you’re behind everyone else.[Student F]

Well I think like it helps when you have your little private discussion, it’s much easier to go from answering a question in your own head and then answering it or talking to all your peers …. and then explaining it to the whole class rather than just asking the question to the whole class and then you’re going straight from answering it in your own head to explaining it to three hundred people.[Student D]

When the lecturer asks us questions, when someone answers, it makes me feel more comfortable to ask questions and stop the lecturer. I think when the lecturer engages with the audience, it feels more inclusive and that it is acceptable and not awkward to ask questions.[Student I]

6.2. Stimulating Engagement

But using interactive tools certainly worked and it works for me because it makes me think in the lecture rather than just taking a bunch a’ stuff down and having to think about it later.[Student F]

It kind of just makes the lectures a bit more enjoyable and interesting cause you’re kind of more involved with it.[Student A]

Whereas obviously in physics lectures that doesn’t happen because you’re just kind of listening and even if you’re writing notes you have the kind of time and explanations on like the paper or on the board.[Student A]

6.3. Supporting Responsiveness

[the graphs are] definitely the most helpful … and whilst at the same time you have your individual feedback as well’.[Student F]

I think that’s probably for his own sort of understanding of how the class is getting along and how we as students think we need to solve the questions.[Student D]

It gives an image of how many people understand what is going on in an exercise and then Dr. Ross knows which topics he has to focus more on.[Student E]

Whereas previously I’ve just had lecturers who, it just seemed like they had a narrative that they needed to lecture us on. And basically just went from one point to another and just kept going, just sort of like a train without a stop’.[Student D]

‘At the end of each quiz we are asked to leave our comments on the quiz what we found hard/interesting Ross uses the data to organize the lectures for the following week and we go through the hard parts of the quiz’.[Student G]

7. Discussion and Implications for Practice

7.1. Student-Student Dialogue

7.2. Teacher-Student Dialogue

7.3. Student-Content Dialogue

8. Limitations

9. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In this paper I use the term ‘large class’ rather than ‘lecture’ to refer to the in-person learning environment, as the latter tends to be associated with a particular type of pedagogy in which a person stands at the front of the class and talks while the students listen and take notes. In practice a variety of pedagogies may be used, and the focus of this work is large classes which are taught using a flipped, active learning approach. |

References

- Abeysekera, L., & Dawson, P. (2015). Motivation and cognitive load in the flipped classroom: Definition, rationale and a call for research. Higher Education Research & Development, 34(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Akçayır, G., & Akçayır, M. (2018). The flipped classroom: A review of its advantages and challenges. Computers & Education, 126, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T., Liam, R., Garrison, D. R., & Archer, W. (2001). Assessing teaching presence in a computer conferencing context. Journal of the Asynchronous Learning Network, 5(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, T. M., Leonard, M. J., Colgrove, C. A., & Kalinowski, S. T. (2011). Active learning not associated with student learning in a random sample of college biology courses. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 10(4), 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitakis, J. (2014). Massification and the large lecture theatre: From panic to excitement. Higher Education, 67, 735–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basken, P. (2023, December 6). Class attendance in US universities ‘at record low’. Times Higher Education. Available online: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/class-attendance-us-universities-record-low (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Bates, S., & Galloway, R. (2012, April 12–13). The inverted classroom in a large enrolment introductory physics course: A case study [Conference session]. HEA STEM Learning and Teaching Conference, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, T. (2023). Discussion-based online teaching to enhance student learning: Theory, practice and assessment. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, R., & Samarawickrema, G. (2009). Addressing the context of e-learning: Using transactional distance theory to inform design. Distance Education, 30(1), 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, S. L., Li, D., Gross, A., Pallett, W. H., & Webster, R. J. (2013). Transactional distance and student ratings in online college courses. American Journal of Distance Education, 27(4), 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, N. M., Liu, X., & Horissian, K. (2022). Impact of community experiences on student retention perceptions and satisfaction in higher education. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 24(2), 337–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, C., Luu, R., Lai, A., Hsiao, V., Cheung, E., Tamashiro, D., & Ashcroft, J. (2020). Making STEM equitable: An active learning approach to closing the achievement gap. International Journal of Active Learning, 5(2), 71–85. [Google Scholar]

- Cash, C. B., Letargo, J., Graether, S. P., & Jacobs, S. R. (2017). An analysis of the perceptions and resources of large university classes. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 16(2), ar33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Wang, Y., & Chen, N.-S. (2014). Is FLIP enough? Or should we use the FLIPPED model instead? Computers & Education, 79, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. J. (2001). Dimensions of transactional distance in the world wide web learning environment: A factor analysis. British Journal of Educational Technology, 32(4), 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, M. T., Kang, S., & Yaghmourian, D. L. (2017). Why students learn more from dialogue-than monologue-videos: Analyses of peer interactions. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 26(1), 10–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, R. (2014). Interaction ritual chains and collective effervescence. In Collective emotions (pp. 299–311). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cuseo, J. (2007). The empirical case against large class size: Adverse effects on the teaching, learning, and retention of first-year students. The Journal of Faculty Development, 21(1), 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- De Felice, S., Hamilton, A. F. D. C., Ponari, M., & Vigliocco, G. (2023). Learning from others is good, with others is better: The role of social interaction in human acquisition of new knowledge. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 378(1870), 20210357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deslauriers, L., Schelew, E., & Wieman, C. (2011). Improved learning in a large-enrollment physics class. Science, 332(6031), 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doo, M. Y., Bonk, C. J., Shin, C. H., & Woo, B.-D. (2020). Structural relationships among self-regulation, transactional distance, and learning engagement in a large university class using flipped learning. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 41, 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, D. M., Craig, S. D., Gholson, B., Ventura, M., Hu, X., & Graesser, A. C. (2003). Vicarious learning: Effects of overhearing dialog and monologue-like discourse in a virtual tutoring session. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 29(4), 431–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekwunife-Orakwue, K. C., & Teng, T.-L. (2014). The impact of transactional distance dialogic interactions on student learning outcomes in online and blended environments. Computers & Education, 78, 414–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, N. (2005). Learning physics in context: A study of student learning about electricity and magnetism. International Journal of Science Education, 27(10), 1187–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(23), 8410–8415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, K. (2012). Upside down and inside out: Flip your classroom to improve student learning. Learning & Leading with Technology, 39(8), 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Galloway, R. (2023). Case study 1: An introductory physics course. In A. K. Wood (Ed.), Effective teaching in large STEM classes. IOP Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison, R. (2000). Theoretical challenges for distance education in the 21st century: A shift from structural to transactional issues. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 1(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hake, R. R. (1998). Interactive-engagement versus traditional methods: A six-thousand-student survey of mechanics test data for introductory physics courses. American Journal of Physics, 66, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, L. C. (2020). Student engagement in active learning classes. In Active learning in college science (pp. 27–41). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hornsby, D. J., & Osman, R. (2014). Massification in higher education: Large classes and student learning. Higher Education, 67(6), 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J. L., Kummer, T. A., & Godoy, P. D. d M. (2015). Improvements from a flipped classroom may simply be the fruits of active learning. CBE-Life Sciences Education, 14(1), ar5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerez, O., Orsini, C., Ortiz, C., & Hasbun, B. (2021). Which conditions facilitate the effectiveness of large-group learning activities? A systematic review of research in higher education. Learning: Research and Practice, 7(2), 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, M. (2020). Transactional distance and learner outcomes in an online EFL context. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 36, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaoglan-Yilmaz, F. G., Zhang, K., Ustun, A. B., & Yilmaz, R. (2024). Transactional distance perceptions, student engagement, and course satisfaction in flipped learning: A correlational study. Interactive Learning Environments, 32(2), 447–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayaduman, H. (2020). Student interactions in a flipped classroom-based undergraduate engineering statistics course. Computer Applications in Engineering Education, 29, 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothiyal, A., Majumdar, R., Murthy, S., & Iyer, S. (2013, August 12–14). Effect of think-pair-share in a large CS1 class: 83% sustained engagement. Proceedings of the Ninth Annual International ACM Conference on International Computing Education Research (pp. 137–144), San Diego, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Kranzfelder, P., Bankers-Fulbright, J. L., García-Ojeda, M. E., Melloy, M., Mohammed, S., & Warfa, A.-R. M. (2020). Undergraduate biology instructors still use mostly teacher-centered discourse even when teaching with active learning strategies. BioScience, 70(10), 901–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasry, N., Mazur, E., & Watkins, J. (2008). Peer instruction: From Harvard to the two-year college. American Journal of Physics, 76(11), 1066–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D., Morrone, A. S., & Siering, G. (2018). From swimming pool to collaborative learning studio: Pedagogy, space, and technology in a large active learning classroom. Educational Technology Research and Development, 66(1), 95–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughlin, C., & Lindberg-Sand, Å. (2023). The use of lectures: Effective pedagogy or seeds scattered on the wind? Higher Education, 85(2), 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, E. (1999). Peer instruction: A user’s manual. AAPT. [Google Scholar]

- McBrien, J. L., Cheng, R., & Jones, P. (2009). Virtual spaces: Employing a synchronous online classroom to facilitate student engagement in online learning. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 10(3). Available online: https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/irrodl/2009-v10-n3-irrodl05155/1067862ar/abstract/ (accessed on 13 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Moore, M. G. (1983). The individual adult learner. Education for Adults, Adult Learning and Education, 1, 153–168. [Google Scholar]

- Mulryan-Kyne, C. (2010). Teaching large classes at college and university level: Challenges and opportunities. Teaching in Higher Education, 15(2), 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keeffe, P. (2013). A sense of belonging: Improving student retention. College Student Journal, 47(4), 605–613. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, M. (2004). Does active learning work? A review of the research. Journal of Engineering Education, 93(3), 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, P., Li, C. S., & Pickett, A. (2006). A study of teaching presence and student sense of learning community in fully online and web-enhanced college courses. The Internet and Higher Education, 9(3), 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, N. (2002). Beyond interaction: The relational construct of transactional presence. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 17(2), 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöhr, C., & Adawi, T. (2018). Flipped classroom research: From “black box” to “white box” evaluation. Education Sciences, 8(1), 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöhr, C., Demazière, C., & Adawi, T. (2020). The polarizing effect of the online flipped classroom. Computers & Education, 147, 103789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swart, W., Wengrowicz, N., & Wuensch, K. L. (2015). Using transactional distances to explore student satisfaction with group collaboration in the flipped classroom. International Journal of Information and Operations Management Education, 6(1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunggyshbay, M., Balta, N., & Admiraal, W. (2023). Flipped classroom strategies and innovative teaching approaches in physics education: A systematic review. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 19(6), em2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turpen, C., & Finkelstein, N. D. (2010). The construction of different classroom norms during Peer Instruction: Students perceive differences. Physical Review Special Topics-Physics Education Research, 6(2), 020123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, R. R., & Qi, J. (2005). Classroom organization and participation: College students’ perceptions. The Journal of Higher Education, 76(5), 570–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams. (2022, June 9). Class attendance plummets post-Covid. Times Higher Education. Available online: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/class-attendance-plummets-post-covid (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Wolters, C. A., Pintrich, P. R., & Karabenick, S. A. (2005). Assessing academic self-regulated learning. In K. A. Moore, & L. H. Lippman (Eds.), What do children need to flourish? (Vol. 3, pp. 251–270) Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A. K., Bailey, T. N., Galloway, R. K., Hardy, J. A., Sangwin, C. J., & Docherty, P. J. (2021). Lecture capture as an element of the digital resource landscape—A qualitative study of flipped and non–flipped classrooms. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 30(3), 443–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A. K., Galloway, R. K., Donnelly, R., & Hardy, J. (2016). Characterizing interactive engagement activities in a flipped introductory physics class. Physical Review Physics Education Research, 12(1), 010140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A. K., Galloway, R. K., Sinclair, C., & Hardy, J. (2018). Teacher-student discourse in active learning lectures: Case studies from undergraduate physics. Teaching in Higher Education, 23, 818–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A. K., & Labrosse, N. (2023). Large classes in STEM education—Potential and challenges. In Effective teaching in large STEM classes (p. 1). IOP Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J. (2025). Revisiting the theory of transactional distance: Implications for open, distance, and digital education in the 21st century. American Journal of Distance Education, 39(1), 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Transactional Distance Theory Dimensions | Element of Course | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomy | Dialogue | Structure | |

| High | Low | High | Pre-reading |

| High | Medium | High | Pre-lecture quiz |

| High | Low | Low | Students solving problems individually |

| High | High | Low | Students working in small groups |

| Medium | Medium | Low | Class-wide discussion (student questions, lecturer questions) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wood, A.K. “It’s Like a Nice Atmosphere”—Understanding Physics Students’ Experiences of a Flipped Classroom Through the Lens of Transactional Distance Theory. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 921. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070921

Wood AK. “It’s Like a Nice Atmosphere”—Understanding Physics Students’ Experiences of a Flipped Classroom Through the Lens of Transactional Distance Theory. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(7):921. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070921

Chicago/Turabian StyleWood, Anna K. 2025. "“It’s Like a Nice Atmosphere”—Understanding Physics Students’ Experiences of a Flipped Classroom Through the Lens of Transactional Distance Theory" Education Sciences 15, no. 7: 921. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070921

APA StyleWood, A. K. (2025). “It’s Like a Nice Atmosphere”—Understanding Physics Students’ Experiences of a Flipped Classroom Through the Lens of Transactional Distance Theory. Education Sciences, 15(7), 921. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070921