Abstract

This study explored the experiences of Hungarian minority parents of children with severe disabilities from Romania. Examining individual life paths and becoming a parent is difficult in all aspects, but the issue of parental responsibility for raising a child with a severe disability suggests a much more complex approach. Participants were parents (female = 8; male = 3) who were purposively sampled from an urban setting (Bihor area) and whose children attended SEN schools in the same area. Data were collected using semi-structured interviews and were thematically analysed. It turned out from the interviews that the challenges parents of children with severe disabilities encounter at home, school, and in society are accumulated emotional stress and exhaustion; however, they also face material challenges. The analysis also revealed that the parents were unsure of what was expected of them in making educational or habilitation–rehabilitation decisions on behalf of their children. The parents’ difficulty with decision-making and their unpreparedness put them under serious stress, often characterized by depressive life stages. The findings reveal the need for ongoing professional development and the establishment of organizational–community networks. Parents of children with disabilities face serious, unresolved challenges that are difficult to overcome. In order to overcome these challenges, we need to develop policies that take the needs of parents into consideration.

1. Introduction

As the primary socializing environment, family plays an important role in children’s quality of life. Several studies have indicated that society can play an active role in the development of children with severe disabilities by providing services for their families (Kagan, 1999). For children to develop optimally on a psychosocial level, there is a significant role for parents to play (Llewellyn & Hindmarsh, 2015; McLaughlin et al., 2008). Moreover, parents of children with disabilities have complex responsibilities, but our society cannot appreciate their life challenges. This study aims to interpret the voices of parents raising a child with severe or multiple disabilities in the Hungarian minority in Romania. These parents have to take into account special needs, intensive care, development, and education, while the antagonism between institutional services (health, school, medical development) and the needs of the families is also visible. This dependence on others puts parents in a vulnerable position, which reinforces the necessity to examine what families with children with disabilities require (Belényi, 2016; Berszán, 2005).

At the international level, the reform of social values and service structures is becoming more and more prevalent (Cohen & Mehta, 2017; French et al., 2023; Gardiner & Iarocci, 2012; Lipset, 2017), but in Romania, the complex healthcare network should still be improved (Belényi, 2016; Berszán, 2008; Grigoras et al., 2021; Petre et al., 2023). This can be seen, for example: in the lack of organisations providing health-related, social, or legal aid. The level of centralisation of organisations often hinders the function of services. For many families, the constant stress and uncertainty make it difficult to continue the search for real solutions to their problems and also create chaos that negatively impacts their fate. This may then result in divorce, substance abuse, deep and persistent depression, bipolar disorder, etc. A negative outlook on life may also manifest in anger towards professionals (teachers, doctors, specialist care providers developers, or anyone else in the institutions) trying to help them, especially stigmatising them for not performing their job well. Developing a web network of trust is the most sensitive point among parents of children with disabilities (Bolborici & Bódi, 2022), as the aforementioned institutionalised frameworks that centralise complex care into specialist care tend to ignore the psychological wounds of families in most cases, only focusing on specialist development/treatment with an approach described as ‘indelicate coldness’ (Gyarmati, 2020; Neagu, 2021; Soare & Institutul de Investigare a Crimelor Comunismului și Memoria Exilului Românesc, 2013).

In Romania, as typical in other countries and societies as well, negative discrimination is deeply rooted in the social perception of people with disabilities. These attitudes towards them can lead to exclusion, marginalisation, and a lack of opportunity. These may come from fear, or a lack of knowledge regarding impairments. People with disabilities frequently struggle to obtain and retain employment due to employer biases or worries about accommodation expenses and productivity. This challenge affects not only adults but children as well. Children with disabilities may experience prejudice in obtaining a quality education, regarding admission to mainstream schools, lacking appropriate modifications, and having limited access to inclusive learning settings. This stigma can emerge in a variety of ways, including bullying, patronising behaviour, and social avoidance. Physical barriers in the built environment, transportation, and public amenities can limit the mobility and independence of people with disabilities, compounding their isolation from society (Baciu & Lazăr, 2017; Birau et al., 2019). While it is difficult to eliminate the stigmas carried over from the past, it is not mainly the task of families to remove them, but that of the majority of society (Neagu, 2021; Stuart, 2016). The family’s responsible attitude can help overcome the dilemmas of equal opportunities, and this study aims to provide support by presenting and analysing exceptionally difficult life situations (Orvos-Tóth, 2018).

1.1. Transgenerational Trauma and Resilience in the Hungarian Minority in Romania

The Hungarian minority in Romania has a deeply interwoven history marked by resilience in the face of communal trauma. Following the Treaty of Trianon in 1920, the Hungarian population in Transylvania, now part of Romania, experienced significant social and cultural upheaval. As of the 2011 census, this minority constituted 6.1% (1,227,623 individuals) of Romania’s population. Despite historical adversities, including systemic marginalization and forced assimilation, the Hungarian community demonstrated remarkable adaptive capacity, preserving their cultural identity through renewal and social cohesion (Berry et al., 2021; Dani, 2016; Székely, 2015).

Recent research in transgenerational trauma highlights how chronic stressors, such as forced minority existence, leave epigenetic marks that influence gene expression across generations (Falus et al., 2015; Gardner et al., 2020). Mechanisms like inherited memory, cultural traditions, and post-memories further underscore the enduring psychological and social ramifications for subsequent generations (Cicchetti & Valentino, 2015; Dani, 2016; Romsics, 2020). Transgenerational trauma refers to the psychological and emotional effects of traumatic experiences that are passed from one generation to the next. These traumas may stem from collective events, such as wars, forced migration, or systemic discrimination. In the context of this study, transgenerational trauma specifically addresses the chronic stress and societal marginalization experienced by the Hungarian minority in Romania, shaped by historical events like the Treaty of Trianon and the Ceaușescu regime’s policies. This concept helps to explain how these shared adversities continue to affect family dynamics, parenting practices, and the perception of disability within these communities.

Epigenetic changes are modifications to gene expression that occur without altering the underlying DNA sequence (McCulley, 2024). These changes can be triggered by environmental factors, such as stress, diet, or exposure to toxins, and may be inherited by subsequent generations. Research in epigenetics has shown that chronic stressors, like those associated with transgenerational trauma, can influence gene activity linked to mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety. In this study, epigenetic changes serve as a theoretical framework to explore how historical and familial stressors may contribute to the intergenerational transmission of vulnerabilities, including those impacting families raising children with disabilities (Bowers & Yehuda, 2020).

This legacy is particularly burdensome for families with children with disabilities. The concept of “socially dependent”, introduced in the 1970s, institutionalized a narrative of exclusion, prioritizing state care over familial bonds. Institutionalization became a political tool to obscure societal issues, leaving indelible scars on affected families. Although legislative strides have been made toward inclusivity, gaps in access to state-subsidized services persist, perpetuating inequality (Belényi, 2011; Soare & Institutul de Investigare a Crimelor Comunismului și Memoria Exilului Românesc, 2013).

The Ceaușescu regime’s Decree 770 (1966), which banned abortion, exemplifies how historical policies exacerbated transgenerational trauma. The ban resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands of women and saw a proliferation of neglected and institutionalized children, often housed in overcrowded facilities derisively referred to as “child lagers” (from the Romanian Leagan, meaning cradle). By 1989, over 13,000 children were institutionalized in Romania, many labeled nerecuperabili—a term denoting individuals deemed irredeemable, synonymous with social death (Neagu, 2021).

1.2. Legacy of Institutionalization Impact on Children with Disabilities and Their Families in Post-Regime Romania

The societal perceptions of people with disabilities are intricately linked to the post-traumatic experiences of families shaped by historical policies like the 770 Decree. Epigenetic mechanisms provide valuable insights into how chronic stress, stemming from these experiences, may contribute to certain illnesses, including psychiatric disorders (Lickliter & Honeycutt, 2013). The intergenerational transmission of trauma not only affects the health and well-being of individuals but also profoundly shapes family dynamics and coping mechanisms. This study’s interviews highlight how coping with a disability as a shared family burden influences life trajectories, often introducing emotional, social, and financial strain. Furthermore, the narratives reveal a lack of adequate supportive environments, organizations, and social services, emphasizing the enduring systemic barriers faced by these families. By examining these transgenerational patterns and the systemic shortcomings, the study underscores the urgent need for more inclusive support structures to address the compounded challenges of disability and historical trauma.

In 1997, the reforms began, proclaiming the principles of decentralisation and renewal. The main objective of the reforms was to decentralize power and decision-making authority from the central government to local governments. The aim was to delegate responsibility and resources to regional and local governments, enabling them to better address the needs and priorities of their respective communities (Dogaru & Chitescu, 2020). As Romania is unable to take stock of the damage caused by the Decree, it is still unclear how many families fell victim to the abortion law under the Ceaușescu regime (Neagu, 2021), and what traumas the current population carries, both in terms of perceptions of disability and equal opportunities. By looking at the historical context of the abortion ban, we can understand the root causes of many negative issues related to disability—such as the lack of social services, an unsupportive environment or a lack of an organisation to help. The results showed that the socioeconomic status of those born after the abortion ban was implemented had a significant impact on their educational and labour market achievements as adults (Pop-Eleches, 2006).

Moving away from the medical model of disability in Romania is still problematic. The Western equal opportunities movements are associated with the Warnock Report, which introduced an integrative or inclusive approach to pedagogy, as well as the concept of special educational needs (Dogaru & Chitescu, 2020). The Report also abolished categories of disability, and pejoratively conceptualised negative attitudes towards the word ‘disability’. It drew attention to the positive portrayal of the potential and possibilities that lie within every child, regardless of the severity of the disability. Romania, however, is still characterised by a secretive approach and struggles to deal with inherited trauma. The introduction of a triple system of categories of disability—curable, partially curable, and incurable—will be a blight on generations. The incurable, many of whom are children with mild to moderate disabilities, experience great suffering, and are confined within institutional settings, characterized by images of children burned by frost, bleeding from rat bites, and locked in cages (Soare & Institutul de Investigare a Crimelor Comunismului și Memoria Exilului Românesc, 2013). The post-revolutionary Romanian government had to address the issue of high numbers of institutionalized children. During Ceausescu’s regime, he implemented policies aimed at increasing the birth rate, resulting in numerous families having more children than they could afford. As a result, many children were left in orphanages with inadequate medical and social care, leading to a high rate of mortality and developmental issues (Hjorthold, 2017). The importance of the mother–child relationship, based on the attachment theory of the 1960s (Ainsworth & Bell, 1970; Bowlby, 1969), was replaced in Romania by the image of the working comrade who can have four, five, or even more children and who, after the third month following childbirth, returns to work immediately because this is what the Greater Romania Party expected of her. She left her children to institutions and the care of grandmothers and relatives.

Epigenetic studies provide a framework for understanding how environmental stressors such as poverty, stigmatization, and institutional neglect manifest across generations. These influences, extending from prenatal to multigenerational environments, suggest a transgenerational phenomenon that reinforces cycles of trauma (Brezeanu, 2021; Krippner & Barrett, 2019). The legacy of Decree 770 illustrates the profound intersection of political policy, disability stigma, and familial disempowerment, underscoring the need for systemic reforms to support marginalized families.

The horrors of the 770 Decree are still with us today, recounted or silenced by our mothers, grandmothers, aunts, and distant female relatives. The perceptions of people with disabilities are also linked to this post-traumatic experience, and epigenetic mechanisms can shed light on the causal background of certain types of illness, as research on this topic has also discovered in the background of psychiatric illnesses (Babik & Gardner, 2021). The family–history aspect of transgenerational involvement can also be found in the interviews in this study.

The term “disabled” in Romania refers to persons with long-term physical, mental, intellectual, or sensory impairments that interact with a variety of barriers. Many disabilities (namely, ASD, ADHD, and some rare genetic disorders) generally remain unrecognized or are not diagnosed or treated early. Due to the lack of early intervention, the disabled person is described by the medical staff as having an irreversible condition/severe disability (Hurjui & Hurjui, 2018).

In this study, “permanent or long-term care” refers to the ongoing and sustained support provided to children with severe disabilities, encompassing a wide range of physical, emotional, social, and educational needs that persist throughout their lives. This type of care is characterized by its duration and intensity, often requiring lifelong planning and support from family members, caregivers, and professionals (World Health Organization, 2022). For children with severe disabilities, permanent or long-term care often involves daily assistance with basic activities such as mobility, communication, personal care, and access to therapy and education (Olusanya et al., 2022). Additionally, it includes navigating complex healthcare systems, advocating for inclusive education, and planning for transitions into adulthood, including vocational training or supported living arrangements (National Research Council, 2012). In this study, the term also reflects the unique burdens faced by families, particularly those in minority communities, as they contend with limited access to specialized services and institutional support. These caregiving arrangements are shaped by cultural, economic, and systemic factors, highlighting the need for adaptable, family-centered approaches to ensure both the child’s well-being and the caregiver’s resilience (Romanian Ministry of Health, 2020; UNICEF, 2023). Within the context of Romanian minority families, this operational definition serves as a foundational element for understanding the challenges and social dynamics explored throughout the study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Questions

We focused on two questions. Firstly, to what extent does coping with a disability, as a shared family burden, affect—or s/has affected—the lives of the family and the life trajectories of family members? Secondly, what supportive environment, organisation, or social services were available to the family?

2.2. Research Design

This study employed a qualitative research design using grounded theory methodology to explore the lived experiences of Hungarian minority parents raising children with severe disabilities in Romania. Grounded theory was selected because it enables theory development directly from empirical data, making it well-suited to explore complex, under-researched phenomena without pre-existing assumptions. The design was further supported by the use of semi-structured interviews, allowing for in-depth, flexible data collection tailored to participants’ narratives.

2.3. Development of the Interview Tool

The interview guide was informed by both a review of relevant literature and the first author’s extensive expertise as a Special Education Needs (SEN) teacher. It was designed to capture the complexity of parental experiences while allowing flexibility for participants to express themselves in depth. Key areas of inquiry included family dynamics, access to resources, and perceptions of societal attitudes toward disability. The questions were open-ended to encourage rich narratives and tailored to align with the cultural and contextual specifics of minority families in Romania.

2.4. Questions and Themes

Examples of the questions used include: personal background: “Can you tell me about yourself and your family situation?”; diagnosis journey: “How did you come to learn about your child’s condition, and how did you process the diagnosis?”; daily challenges: “What are the main challenges you face as a parent raising a child with a disability?”; support and resources: “What kinds of support have you found most helpful, and where do you feel there are gaps?”; future aspirations: “What are your hopes and concerns for your child’s future?”; These questions were organized to flow naturally, beginning with general topics about family life and progressively addressing more specific issues, such as coping mechanisms and experiences with institutional support.

2.5. Interview Language

The interviews were conducted in Hungarian, the native language of the participants, to facilitate clear and authentic communication. They took place in quiet, comfortable settings, such as classrooms, after regular class hours. These locations were chosen to ensure privacy and a relaxed environment for participants to share their experiences openly. As the authors are fluent in Hungarian, no translator was required.

To ensure the reliability and validity of the data, several measures were implemented throughout the research process. Credibility was established through prolonged engagement with participants, which allowed for the development of trust and a deeper understanding of their perspectives. Transferability was ensured by providing detailed descriptions of the participants’ context, enabling readers to evaluate the applicability of the findings to similar populations. Dependability and confirmability were supported by maintaining a reflexive journal to document personal reflections and potential biases, ensuring transparency in the research process. Additionally, peer debriefing sessions with colleagues were conducted to validate interpretations and ensure they were firmly grounded in the data. As the primary researcher and interviewer, the first author brings over a decade of experience as a Special Education Needs (SEN) teacher, with expertise in working closely with families of children with disabilities. This professional background was instrumental in designing the study and interpreting the data, providing valuable insights into the lived experiences of participants. Despite this, conscious efforts were made to remain objective and to allow participants’ voices to guide the findings, ensuring that their perspectives were authentically represented in the study.

2.6. Research Setting

The interviews were conducted between September 2021 and June 2022, during the afternoons to accommodate participants’ schedules. The sessions took place primarily in schools located in Bihor County, Romania, in designated quiet areas or private rooms. These locations were chosen to ensure a comfortable and confidential setting where participants could freely share their experiences. Conducting the interviews in familiar and accessible environments also helped establish trust and encouraged open communication, fostering a rich and authentic data collection process. This contextual detail has been added to the methodology section to provide readers with a clearer understanding of the research setting.

2.7. Sample and Procedure

Participants were parents from a purposively selected sample (11 interviews with 8 females and 3 males were recorded and analysed using Atlas.ti software (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, 2022, coding + analysis), from an urban environment (Bihor County and surroundings), whose children are enrolled in special education in the same area in special education schools. The participants in this study voluntarily answered the interview questions without receiving any form of financial or material compensation. Six of the eight mothers provide permanent and long-term care for their children, permanent or long-term care for impaired children is a crucial measure that involves providing unwavering support, assistance, and essential services to cater to the complex requirements of children with disabilities over an extended period of time. Three mothers and two of the fathers work full-time. Six interviewees are raising their disabled children alone (five women and one man), and five parents live in a family with two parents living together (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Coding characteristics.

2.8. Data Analysis

The coding process in this study followed a structured approach to ensure consistency and reliability. Coding was conducted in two iterations, with a thorough comparison performed to evaluate the reliability of the codes. Across 11 interviews, the first round yielded 1250 codes, while the second round resulted in 1200 codes. A total of 1113 instances showed agreement between the two coding rounds.

To calculate inter-rater reliability, Cohen’s Kappa was employed:

Observed Agreement (Po) was calculated by dividing the number of agreed coding situations (1113) by the total number of coding situations, determined as the average of the two rounds of coding:

Observed Agreement

Expected Agreement (Pe) was calculated using the proportions of codes from the two rounds:

Proportion of codes in the first round

Proportion of codes in the second round

Expected agreement

Cohen’s Kappa (κ) was calculated using the formula:

Calculation formula:

Although the Cohen’s Kappa value of approximately κ −0.091, suggests slightly lower agreement than chance, this negative value may reflect minor variations in coding rather than significant inconsistencies. Overall, the coding process achieved acceptable reliability, supported by triangulation with thematic analysis to ensure internal and external validity (Sántha, 2009; Sántha & Gyeszli, 2022).

The themes and subthemes were developed from coded data following grounded theory principles. Categories were constructed to represent major themes such as Traumatic Loss, Sense of Belonging, and Role Conflict. Within these, subthemes like Loss of Normality and Prejudices captured more nuanced participant experiences. The distribution of codes across themes was quantified and illustrated in the below table to highlight key findings (Table 1).

Responses to the semi-structured interview questions were recorded during face-to-face interviews (45–50 min). After the audio recordings were transcribed, they were coded and analysed by the first author. Following the Grounded Theory (Glaser & Strauss, 2017), we tried to stay removed from our knowledge of the subject (one of the authors, as a practising special education teacher, considers the present research important and incomplete but still considers it important to be able to investigate it with a researcher’s eye), in order to formulate our theoretical justifications, starting from the data obtained from the interview analyses, and moving steadily along the gradients of abstraction. The interview questions served only as a starting point, providing the opportunity for free-association reflections and discussion of issues relevant and important to the interviewees and related to the topic (Corbin & Strauss, 2008; Henwood & Pidgeon, 2003). The analysis was structured around three main topics, which were developed by combining concepts from the data analysis and the literature. Based on the methodology of the Grounded Theory, we followed a kind of constructivist reporting process, thus focusing on the ‘what’ and ‘how’ questions (Kálmán & Könczei, 2022; Sántha, 2011; Sántha & Gyeszli, 2022). Grounded theory is a research method that is well-suited for investigating topics that are not well-known or have not been studied extensively. It allows researchers to develop theories and explanations based solely on the data collected, without any preconceived notions or hypotheses. This makes it a valuable tool for gaining new insights and understanding phenomena from the perspective of the participants themselves. We included three main and several sub-themes in the analysis in a typological order. In the process of interpretation, open coding was used along with constant comparisons of concepts and ideas. The coding process led to a summary of categories that emerged from the data using axial and selective coding. As part of the process of developing a theory, it is necessary to construct networks of terms and concepts as well as the relations that link them.

The analysis was divided into two phases. In the first phase, the corpus was contextualised by developing categories step-by-step, highlighting the intertextual meanings, while in the second phase, the text was analysed in detail using open, axial, and selective coding. The three main typologies are traumatic loss, sense of belonging, and role conflict. The typologies were not arranged in a hierarchical order since each topic and sub-topic raises relevant issues, but the coding results were used to juxtapose the sub-topics and related topics, which, when built around the main typologies, provide a deeper insight into the family history aspects of transgenerational involvement.

The grounded theory methodology was selected for this study to explore and generate insights into the lived experiences of Hungarian minority parents raising children with severe disabilities in Romania. Grounded theory is particularly suitable for this context because it allows for the emergence of themes and patterns directly from participant narratives, providing a bottom-up approach to understanding complex phenomena. This methodology aligns with the study’s aim to address under-researched areas by constructing a theoretical framework grounded in the data.

2.9. Research Trustworthiness

Semi-structured interviews were chosen as the primary data collection method due to their flexibility and depth. They enabled participants to share detailed accounts of their experiences while allowing the interviewer to probe further into specific areas of interest. This approach balanced consistency, through a set of guiding questions, with adaptability, allowing participants to express themselves freely and highlight issues most significant to them. Open-ended questions encouraged the exploration of diverse perspectives, which is essential for uncovering nuanced insights in a population with varied experiences and challenges.

The duration of the interviews was tailored to the participants’ availability, lasting between 45 and 90 min, conducted in quiet and familiar settings, such as schoolrooms, to ensure comfort and confidentiality. While relatively brief, the depth of the discussions was ensured by focusing on key thematic areas, such as family dynamics, access to support services, and the interplay of disability and minority identity. This structure ensured methodological rigor without overburdening participants, many of whom face significant time constraints due to caregiving responsibilities.

Grounded theory further supports this study by facilitating iterative analysis. Themes were derived inductively, allowing the data to inform the development of theoretical constructs, rather than imposing pre-existing frameworks. This adaptability is essential in exploring under-researched areas where existing theories may not fully capture the unique intersections of culture, ethnicity, and disability.

The combined use of grounded theory and semi-structured interviews ensures that the findings are both rooted in the participants’ lived experiences and rigorously analyzed, providing a comprehensive understanding of the challenges faced by these families. This approach demonstrates methodological robustness while being sensitive to the contextual and cultural nuances of the study population.

3. Results

The study included 11 parents (8 mothers and 3 fathers) of children with severe disabilities enrolled in special education programs in Bihor County, Romania. Each participant has a child diagnosed with one or more conditions, including Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Intellectual Disability (ID), and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). These families reflect diverse caregiving situations—some are single parents, others live in two-parent households—with varying levels of access to formal support systems (see Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the study participants.

Table 3.

Participants.

The study identified three core themes reflecting the lived experiences of Hungarian minority parents raising children with severe disabilities in Romania: Traumatic Loss, Sense of Belonging, and Role Conflict (Table 4). These themes emerged from thematic analysis of 11 in-depth interviews and are detailed in Table 4 below, which summarizes the themes, subthemes, and their conceptual links.

Table 4.

The Main Themes and Associated Subthemes.

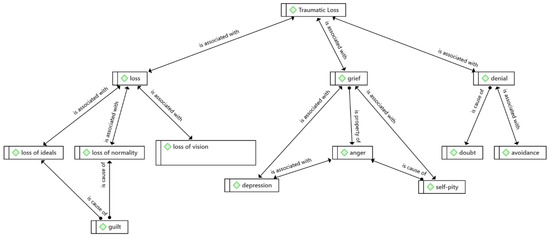

The typology of traumatic loss was present in all interviews, and in the analysis, it is linked to three sub-topics: the conceptual triad of loss, grief, and denial, which can also be divided into smaller sub-topics, as shown in the figure. Highlighting the content associated with these can provide a deeper insight into the intertextual link between trauma and loss (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the First Main Theme Entitled “Traumatic Loss”. Authors’ own edition, created with Atlas.ti.

Text highlights related to the typology of Traumatic Loss:

Well, what will happen to her when I’m gone… Who will take care of her? So I want her to be as independent as possible. If she grows up… She is 18… Then, she will have a place to go, to have company. Because you cannot even keep her at home when she is 18… Because you can’t take her to the park when she is over 18.(2:33, participant A, mother of an 8 years old boy/ID)1

It is very difficult! But again, with an average child, I don’t know… The hardest thing for him, of course, is what will happen to him later when I won’t be there. Nothing else… it is… We will solve the rest, we will solve everything else until then. But what about him? What will happen to him when I won’t be there? What will happen to him? (takes a long pause, sighs, tears in his eyes)(1:78, participant E, mother of an 8 years old boy, ASD)

Mostly, general loss, grief, and denial could have been seen in the interviews. The disruption of daily life is typical since traumatic loss can disrupt the established routines and dynamics within the family. Negative perceptions related to the future, e.g., loss of vision was also mentioned. Beside feeling a significant loss, other negative emotions like anger and doubt and negative psychological statuses like depression were also visualised. Families raising children with disabilities face unique obstacles, including financial pressure, social isolation, navigating healthcare and education systems, and caregiving. These challenges can be stressful, and in the face of severe loss, can compound grief.

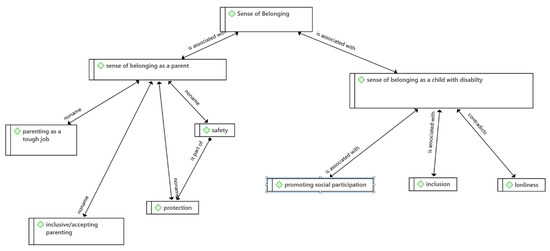

The other emerging typology raises the issue of the sense of belonging, i.e., belonging as a parent and belonging as a disabled child. Here, the most striking thing is the pertinent parenting image, which is prominent throughout but can only be truly interpreted in the highlighted passages (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the Second Main Theme Entitled “ Sense of Belonging”. Authors’ own edition, created with Atlas.ti.

Text highlights related to the typology of Sense of Belonging:

Well, that is why it’s very difficult for me because he doesn’t talk about school or his feelings, but there is no example! And again, the example of coming home to my husband, couple, etc., I tell him… so he doesn’t have this example of people talking. We all come home… me, mum does her thing, she takes the tablet, because they have not seen each other all day, and then, the only things left are… to eat, to have a bath, to go to bed, so it’s left to the most routine form of conversation. And, if I try to open it up, I will ask him, “How was school? Did you study, did you write, did you count? I just get nice echoes back; I don’t get anything from him yet, actually.(4:64, participant D, mother of a 12-year-old girl, ID)

It’s hard (he pauses, looks in front of him), well, even my brother and I can talk like that, and I try to use quotes quote (laughs embarrassedly), and stuff like that… improve myself, so I don’t fail, because if I fail, X (the child’s name) will take it from me. I was just talking to my brother, and I said that I am not even allowed to be angry here, I am not even allowed to be hysterical (laughs); that’s a luxury for me.(2:10, participant B, mother of a 10 years old boy ASD/ADHD)

It is clear that sense of belonging is significant among the interviewees; however, this is also disrupted due to the social isolation reported by the parents. Experiencing social isolation and facing stigmas due to the child’s condition is typical. The traumatic loss of a disabled child can intensify this feeling of being isolated, as the family may experience difficulties in finding understanding and support from their immediate community or extended social network. The traditional breadwinning role of fathers in families with disabled children is causing a strain on their relationships. This pressure often leads to one-third of men losing confidence in their ability to care for their child. Fathers who care for a disabled child are often faced with financial pressure, which forces them to work long hours.

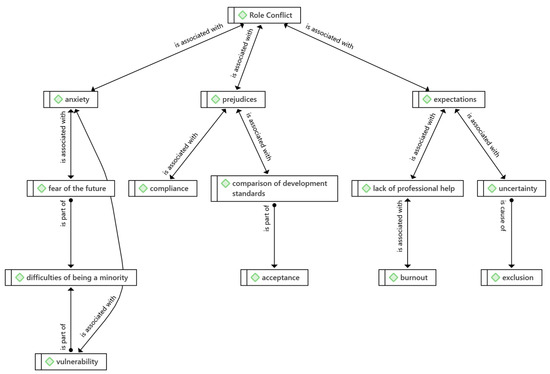

The typology of role conflict is composed of three sub-topics and several smaller thematic links, such as those shown in the figure (see Figure 3): anxieties, prejudices and expectations, and difficulties arising from being a minority, which is closely linked to anxieties and fears about the future and feelings of vulnerability. Acceptance also comes up several times in the analyses, but there is a contrast in terms of prejudice.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the Third Main Theme Entitled “The Role Conflict”. Authors’ own edition, created with Atlas.ti.

4. Discussion

4.1. Findings

The sense of loss experienced as trauma is a significant burden on the shoulders of families, which becomes heavier without effective help and community involvement (Florian et al., 2016). The results of qualitative research show that changing their child’s condition encourages parents to cope with internal conflicts. Mothers live in close symbiosis with their children, creating a unique closed world. Fathers find it more difficult to accept the idea of this closed world, and they look to blame society (Kandiyoti, 2016; Zoja, 2018). In the analysis, mothers’ reaction mechanisms point toward struggle and acceptance, while fathers grind along in the dilemma of the immediate environment and wider social acceptance (Findler et al., 2016; Harvey, 2015; Jackson, 2021). Coping with a disability as a common family burden has a significant impact on the lives of families, as families with a disabled child live in difficult circumstances. The needs expressed by parents are, in many cases, in line with findings from international research, which suggest that acceptance and understanding of children with disabilities can be framed in terms of engaging properly functioning families and supportive relationships while providing inclusive-environmental and social opportunities.

Table 5 summarizes the major themes and subthemes identified in this study, offering insights into the lived experiences of Hungarian minority parents raising children with severe disabilities in Romania. The table juxtaposes findings from this study with relevant international research, highlighting both similarities and contextual differences. Themes such as Traumatic Loss, Sense of Belonging, and Role Conflict reveal the psychological and social burdens on parents, while Barriers to Support and Coping Strategies underscore the systemic challenges and adaptive mechanisms unique to the Romanian context. This comparative analysis provides a comprehensive understanding of the challenges faced by these families and situates the findings within a global framework.

Table 5.

Comparative Analysis of Key Themes from the Study and International Research.

The findings presented in Table 4 are crucial for understanding how the intersection of minority status, systemic barriers, and disability shapes parental experiences in Romania. For Special Education Needs (SEN) education, these findings emphasize the need for culturally sensitive and community-based approaches to support families. While international research points to the benefits of inclusive policies and deinstitutionalization (Cienkus, 2022; Podgórska-Jachnik, 2024), Romania lags in implementing these reforms, leaving parents to rely heavily on informal networks and personal resilience. The themes of Traumatic Loss and Role Conflict illustrate the significant emotional toll on caregivers, suggesting the need for targeted mental health interventions and professional support (Llewellyn & Hindmarsh, 2015). Additionally, fostering a Sense of Belonging by reducing social stigma and encouraging inclusion is paramount for creating an environment where both parents and children feel supported (D’Eloia & Price, 2018; Juvonen et al., 2019). By addressing Barriers to Support, particularly in rural and minority areas, Romania can align with international best practices in SEN education. The findings also highlight the importance of advocacy and peer networks as coping strategies, underscoring their relevance for policy development and practical interventions in educational and social care systems (Petre et al., 2023; Tokić et al., 2023). This analysis not only informs future research but also provides actionable insights for improving the quality of life for families navigating the challenges of disability in Romania.

International comparisons further contextualize these findings. Parents raising children with disabilities across various countries report similar experiences of emotional distress, role conflict, and social isolation. For example, studies from the UK, Australia, and Canada (Llewellyn & Hindmarsh, 2015; Canary, 2008; Morrison, 2004) describe how parents face persistent stress due to caregiving responsibilities, lack of inclusive education, and navigating complex service systems. Research from the United States and Western Europe highlights the protective role of peer support groups, counseling services, and structured interventions (Singer, 2007; Gore et al., 2024). However, these supports are often unavailable or underdeveloped in Romania, particularly for minority families. Furthermore, the added layers of transgenerational trauma and minority status distinguish the Hungarian parents’ experiences in Romania from those documented in majority populations elsewhere. Unlike parents in countries with more established disability rights frameworks and deinstitutionalized support systems (Cienkus, 2022; Montenegro et al., 2023), Hungarian minority parents in Romania must navigate not only disability-related challenges but also systemic barriers rooted in cultural marginalization and historical neglect. This intersectionality amplifies parental stress and underscores the need for tailored, culturally sensitive interventions.

4.2. Interpretations

The need for belonging focuses on adaptive approaches, specifically examining how resources in minority Hungarian communities—broken down into social, environmental, and relational systems—support families raising a disabled child and foster mutual support (Berszán, 2017). Counseling, therapy, and support groups can play a crucial role in helping family members cope with their grief, process emotions, and develop strategies to manage challenges. However, it is important to note that access to these services may vary depending on location and available resources. International research highlights several interventions for managing parental anxiety and guilt. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), and narrative therapy have all been used to reduce emotional strain in parents of children with disabilities (Hutchinson et al., 2014; Singer, 2007). These approaches help parents reframe negative thoughts, develop coping skills, and build emotional resilience. Parent training programs like the Early Positive Approaches to Support (E-PAtS) in the UK also offer group-based learning for emotional regulation, stress relief, and long-term planning (Gore et al., 2024). These models could serve as valuable templates for similar programs in Romanian minority communities.

Families reported experiencing role conflicts, a situation where individuals feel they must fulfill multiple roles or responsibilities that may conflict or be demanding. These experiences differ based on the severity of the disability, the availability of resources, and individual circumstances. Addressing role conflicts requires cognition, communication, and support through open communication, establishing support networks, and seeking internal help, along with self-care strategies. An international comparison highlights both universal challenges and culturally specific dynamics in parenting children with severe disabilities. Globally, parents often face emotional distress, social isolation, and a struggle to balance caregiving with work and social life (Llewellyn & Hindmarsh, 2015; Hutchinson et al., 2014). However, in many Western countries, structured support systems, such as early intervention services, inclusive education frameworks, and family-centered mental health programs, help alleviate some of these burdens (Canary, 2008; Gore et al., 2024). In contrast, parents in Romania, particularly from minority groups, encounter significant gaps in service accessibility and cultural sensitivity. The findings of this study illustrate how these parents must rely heavily on personal resilience and informal support networks, which is a less common necessity in countries with robust disability policies and community-based care models (Montenegro et al., 2023; Dempsey et al., 2016). Additionally, the Romanian context reflects a legacy of institutionalization and social stigma, which is less prevalent in countries where deinstitutionalization and disability rights movements have transformed public attitudes (Cienkus, 2022). This comparison underscores the urgent need for Romania to adapt international best practices, such as parent training programs, inclusive education initiatives, and coordinated care pathways while tailoring them to the socio-historical realities and cultural identity of minority families.

4.3. Recommendations

The pedagogical study of families with children with disabilities and institutional relationships is still neglected in the field of Hungarian educational research in Romania (Berszán, 2017; Dan et al., 2023; Soare & Institutul de Investigare a Crimelor Comunismului și Memoria Exilului Românesc, 2013). This gap underscores the importance of focusing on the theme of the present study and the challenges faced by these families. Despite the immense challenges, families in Romania with disabled children also demonstrate resilience and personal growth. Seeking professional help and connecting with support networks are essential for families. Programs aimed at fostering community support, increasing access to services, and creating inclusive environments would benefit these families and alleviate their burden. Support can also be devised through low-cost, community-anchored approaches such as parent-led peer groups, mobile social worker networks, and school-based mental health outreach programs. In other countries, such as Ireland and Canada, these models have reduced caregiver burnout and improved emotional well-being (Dempsey et al., 2016; Powers et al., 2020). Embedding these initiatives into Romania’s special education framework could offer scalable and culturally adaptable solutions.

Parents of children with severe disabilities need access to peer support networks and training programs that equip them with knowledge about resources and strategies to manage caregiving responsibilities and role conflicts. Advocacy workshops can further empower them to navigate institutional barriers and actively participate in their child’s education and care. Social workers play a vital role in bridging families and services, and their training should focus on understanding the intersectional needs of minority families while promoting inclusive policies and facilitating community partnerships to create localized support systems. Educators, on the other hand, must adopt inclusive pedagogical practices and collaborative frameworks that involve parents in decision-making and ensure adaptive teaching strategies are implemented to foster meaningful education for children with disabilities. Collaboration between minority- and majority-language schools can also promote best practices and inclusivity. Researchers should prioritize studies that explore the intersection of disability, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, as well as the long-term effects of caregiving on family trajectories. Further exploration of community networks, decentralized services, and inclusive education models can provide actionable insights to improve the quality of life for children with severe disabilities and their families while addressing the unique challenges faced by minority communities.

4.4. Limitations

This study highlights critical areas for intervention and policy reform to improve the quality of life for families raising children with severe disabilities. The findings underscore the urgent need for culturally responsive support systems tailored to the unique challenges faced by minority communities. This includes decentralizing and expanding access to professional services, such as counseling, peer support networks, and inclusive educational programs. For policymakers, this study emphasizes the necessity of allocating resources to develop localized and linguistically appropriate support systems that address both the financial and social barriers faced by families.

For practitioners, particularly educators and social workers, the study underscores the importance of fostering inclusive practices that empower parents to advocate for their children and engage in collaborative decision-making. Enhanced training in inclusive pedagogy and family-centered approaches is essential to create supportive environments that accommodate the diverse needs of families.

Future research should build on these findings by exploring longitudinal outcomes for families navigating disability, particularly in minority contexts. Studies focusing on the intersection of disability, cultural identity, and systemic barriers could provide deeper insights into effective support strategies. Additionally, investigating the efficacy of community-based interventions, such as parent networks and peer support groups, could inform scalable models of care and inclusion. By addressing these areas, the field can advance toward a more equitable and supportive framework for families and children with disabilities.

5. Conclusions

Although attitudes toward people with disabilities have shifted significantly in Romania over the last 30 years, the educational system remains strongly segregated, and medical and health services remain rigid. Our research emphasizes the diverse experiences of parents raising disabled children in Romania. Poverty, single parenthood, anxiety, and serious health concerns all interacted to affect the experiences of some Hungarian minority parents raising children with severe disabilities in Romania, according to our findings. Despite their differences, parents raising children with severe disabilities in Romania shared their experiences of continuous struggle, a lack of appropriate support and resources, stigma, and a lack of understanding about living with a disabled child in society. Parents, particularly mothers who were largely responsible for the daily care of their children with severe disabilities, placed their child’s needs over family relationships, social life, work, and education. Families raising children with disabilities often face significant obstacles, including caregiving, financial stress, social isolation, and navigating healthcare and educational systems. Caring for a child with severe disabilities can be an immense financial burden for parents. High medical bills, equipment costs, and treatments limit their capacity to work or pursue education. Dependency on the primary caregiver, typically the mother, exacerbates financial stress. Providing support to families is crucial (Tokić et al., 2023; Zulfia, 2020). A lack of support, vulnerability, misconceptions, and fear of the future were common challenges single parents and their children face. It is, therefore, necessary to consider these broader determinants when developing interventions to improve their quality of life, which may require the implementation of structural and community-level changes. Future research could explore how best practices from international contexts, such as community-based mental health services, inclusive education, and parent advocacy programs, could be adapted to meet the cultural and systemic realities of minority families in Romania.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.A.D. and K.E.K.; methodology, B.A.D.; formal analysis, B.A.D.; investigation, B.A.D.; resources, B.A.D.; data curation, B.A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, B.A.D.; writing—review and editing, B.A.D. and K.E.K.; visualization, B.A.D.; supervision, K.E.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study complies with all regulations. The Ethical Committee of the Doctoral School of Humanities approved this study (2025/1). Informed consent was obtained from the participant(s). The research was conducted ethically, the results are reported honestly, the submitted work is original and not (self-)plagiarised, and the authorship reflects the individual contributions.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. They are available from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Note

| 1 | ATLAS.ti assigns an identifier to each generated quotation by combining the index of the principal text and the first 30 characters of the text segment automatically, e.g., 2:33. |

References

- Ainsworth, M. D. S., & Bell, S. M. (1970). Attachment, exploration, and separation: Illustrated by the behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. Child Development, 41(1), 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH. (2022). ATLAS.ti 22 windows [Software]. ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH. Available online: https://atlasti.com (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Babik, I., & Gardner, E. S. (2021). Factors affecting the perception of disability: A developmental perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 702166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baciu, L., & Lazăr, T.-A. (2017). Between equality and discrimination: Disabled persons in Romania. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 2017, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belényi, E. H. (2011). Fogyatékosság és esélyegyenlőség oktatáspolitikai perspektívában. Új Kutatások a Neveléstudományban, 3(1), 197–206. [Google Scholar]

- Belényi, E. H. (2016). Többszörös kisebbségben: Identitás és oktatási inklúzió egy romániai magyar siket közösségben. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2437/234053 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Berry, S. C., Wise, R. G., Lawrence, A. D., & Lancaster, T. M. (2021). Extended-amygdala intrinsic functional connectivity networks: A population study. Human Brain Mapping, 42(6), 1594–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berszán, L. (2005). A fogyatékos személyek védelme Romániában. Esély, 5, 53–78. [Google Scholar]

- Berszán, L. (2008). Fogyatékosság és családvilágok: A sérült gyermeket nevelő családok életminősége és speciális problémái. Mentor Könyvek Kiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Berszán, L. (2017). A fogyatékos személyek társadalmi integrációja/Egyetemi kézikönyv. Egyetemi Műhely Kiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Birau, F. R., Dănăcică, D.-E., & Spulbar, C. M. (2019). Social exclusion and labor market integration of people with disabilities. A case study for romania. Sustainability, 11(18), 5014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolborici, A.-M., & Bódi, D.-C. (2022). Issues of special education in Romanian schools. European Journal of Education, 5(2), 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, M. E., & Yehuda, R. (2020). Chapter 17—Intergenerational transmission of stress vulnerability and resilience. In A. Chen (Ed.), Stress resilience (pp. 257–267). Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss, Vol. 1: Attachment. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Brezeanu, L. (2021). Acasă. Jurnalul Decretului. Available online: https://jurnaluldecretului.ro/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Canary, H. E. (2008). Creating supportive connections: A decade of research on support for families of children with disabilities. Health Communication, 23(5), 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicchetti, D., & Valentino, K. (2015). An ecological-transactional perspective on child maltreatment: Failure of the average expectable environment and its influence on child development. In Developmental psychopathology (pp. 129–201). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cienkus, K. (2022). Deinstitutionalization or transinstitutionalization? Barriers to independent living for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy, 36, 315. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, D. K., & Mehta, J. D. (2017). Why reform sometimes succeeds: Understanding the conditions that produce reforms that last. American Educational Research Journal, 54(4), 644–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, B. A., Kovács, K. E., Bacskai, K., Ceglédi, T., & Pusztai, G. (2023). Family–sen school collaboration and its importance in guiding educational and health-related policies and practices in the hungarian minority community in romania. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dani, E. (2016). Székelymagyar nemzeti- és kulturálisidentitás-stratégiák a trianoni határokon túl (Székely-hungarian national and cultural identity strategies beyond the trianon borders). Hungarian Cultural Studies, 9, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Eloia, M. H., & Price, P. (2018). Sense of belonging: Is inclusion the answer? In Sport and disability. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey, L., Dowling, M., Larkin, P., & Murphy, K. (2016). Sensitive interviewing in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 39(6), 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogaru, G.-V., & Chitescu, R.-I. (2020, September 4). Reform of public education system in Romania. International Conference Innovative Business Management & Global Entrepreneurship (IBMAGE 2020) (pp. 369–379), Warsaw, Poland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falus, A., Melicher, D., & Purebl, G. (2015). Mentális folyamatok epigenetikai szabályozása. Orvostovábbképző Szemle, XXII(1), 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Findler, L., Klein Jacoby, A., & Gabis, L. (2016). Subjective happiness among mothers of children with disabilities: The role of stress, attachment, guilt and social support. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 55, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florian, L., Black-Hawkins, K., & Rouse, M. (2016). Achievement and inclusion in schools (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, M., Kimmitt, J., Wilson, R., Jamieson, D., & Lowe, T. (2023). Social impact bonds and public service reform: Back to the future of New Public Management? International Public Management Journal, 26(3), 376–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, E., & Iarocci, G. (2012). Unhappy (and happy) in their own way: A developmental psychopathology perspective on quality of life for families living with developmental disability with and without autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 33(6), 2177–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, M., Hutt, S., Kamentz, D., Duckworth, A. L., & D’Mello, S. K. (2020). How does high school extracurricular participation predict bachelor’s degree attainment? It is complicated. Journal of Research on Adolescence (Wiley-Blackwell), 30(3), 753–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (2017). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, J., Rosser, B., Jaremus, F., Miller, A., & Harris, J. (2024). Fresh evidence on the relationship between years of experience and teaching quality. The Australian Educational Researcher, 51(2), 547–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoras, V., Salazar, M., Vladu, C. I., & Briciu, C. (2021). Diagnosis of the situation of persons with disabilities in Romania. Ministreul Municii si Protectiei Sociale. [Google Scholar]

- Gyarmati, B. F. (2020). Analysis of the special education system in Romania. Romanian Journal of School Psychology, 13(26), 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, C. (2015). Maternal subjectivity in mothering a child with a disability: A psychoanalytical perspective. Agenda, 29(2), 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henwood, K., & Pidgeon, N. (2003). Grounded theory in psychological research. In Qualitative research in psychology: Expanding perspectives in methodology and design (pp. 131–155). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjorthold, A. (2017). Social vulnerability factors for children in an institution in Romania. Analele Ştiinţifice Ale Universităţii “Alexandru Ioan Cuza” Din Iaşi. Sociologie Şi Asistenţă Socială, 10(1), 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Hurjui, I., & Hurjui, C. M. (2018). General considerations on people with disabilities. Romanian Society of Legal Medicine, 26, 225–228. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson, M., East, L., Stasa, H., & Jackson, D. (2014). Deriving consensus on the characteristics of advanced practice nursing: Meta-summary of more than 2 decades of research. Nursing Research, 62(2), 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, A. J. (2021). Worlds of care: The emotional lives of fathers caring for children with disabilities. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen, J., Lessard, L. M., Rastogi, R., Schacter, H. L., & Smith, D. S. (2019). Promoting social inclusion in educational settings: Challenges and opportunities. Educational Psychologist, 54(4), 250–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, J. (1999). The role of parents in children’s psychological development. Pediatrics, 104(1 Pt 2), 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kálmán, Z., & Könczei, G. (2022). A taigetosztól az esélyegyenlőségig. Osiris. [Google Scholar]

- Kandiyoti, D. (2016). The paradoxes of masculinity: Some thoughts on segregated societies. In Dislocating masculinity (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Krippner, S., & Barrett, D. (2019). Transgenerational trauma: The Role of epigenetics. The Journal of Mind and Behavior, 40(1), 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Lickliter, R., & Honeycutt, H. (2013). A developmental evolutionary framework for psychology. Review of General Psychology, 17(2), 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipset, S. (Ed.). (2017). Revolution and counterrevolution: Change and persistence in social structures (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn, G., & Hindmarsh, G. (2015). Parents with intellectual disability in a population context. Current Developmental Disorders Reports, 2(2), 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCulley, M. (2024). Epigenetics and health: A practical guide. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, J., Goodley, D., Clavering, E., & Fisher, P. (2008). Families raising disabled children: Enabling care and social justice (2008th ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Montenegro, C., Dominguez, M. I., Moller, J. G., Thomas, F., & Ortiz, J. U. (2023). Moving psychiatric deinstitutionalization forward: A scoping review of barriers and facilitators. Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health, 10, e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, L. (2004). Ceausescu’s legacy: Family struggles and institutionalization of children in Romania. Journal of Family History, 29(2), 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council. (2012). Disability classification in education: A systematic approach to inclusion. National Research Council. [Google Scholar]

- Neagu, M. (2021). Voices from the silent cradles: Life histories of Romania’s looked-after children. Bristol University Press. Available online: https://policy.bristoluniversitypress.co.uk/voices-from-the-silent-cradles (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Olusanya, B. O., Kancherla, V., Shaheen, A., Ogbo, F. A., & Davis, A. C. (2022). Global and regional prevalence of disabilities among children and adolescents: Analysis of findings from global health databases. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 977453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orvos-Tóth, N. (2018). Örökölt sors. Kulcslyuk kiadó. Available online: https://bookline.hu/product/home.action?_v=Orvos_Toth_Noemi_Orokolt_sors&type=22&id=308513 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Petre, I., Barna, F., Gurgus, D., Tomescu, L. C., Apostol, A., Petre, I., Furau, C., Năchescu, M. L., & Bordianu, A. (2023). Analysis of the healthcare system in Romania: A brief review. Healthcare, 11(14), 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podgórska-Jachnik, D. (2024). Interinstitutional support and deinstitutionalization of social services for individuals with disabilities as a context for inclusive education. Edukacyjna Analiza Transakcyjna, 13, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop-Eleches, C. (2006). The Impact of an abortion ban on socioeconomic outcomes of children: Evidence from Romania. Journal of Political Economy, 114(4), 744–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, M. A., Bardsley, J. K., Cypress, M., Funnell, M. M., Harms, D., Hess-Fischl, A., Hooks, B., Isaacs, D., Mandel, E. D., Maryniuk, M. D., Norton, A., Rinker, J., Siminerio, L. M., & Uelmen, S. (2020). Diabetes self-management education and support in adults with type 2 diabetes: A consensus report of the American diabetes association, the association of diabetes care & education specialists, the academy of nutrition and dietetics, the American academy of family physicians, the American academy of pas, the American association of nurse practitioners, and the American pharmacists association. Diabetes Care, 43(7), 1636–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanian Ministry of Health. (2020). Strategic plans for the inclusion of children with disabilities in Romania. Available online: https://anpd.gov.ro/web/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/The-National-Strategy-for-the-Rights-of-Persons-with-Disabilities-An-equitable-Romania-2022-2027.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Romsics, L. (2020). A trianonibékeszerződés. Helikon. [Google Scholar]

- Sántha, K. (2009). Bevezetés a kvalitatív pedagógiai kutatás módszertanába. Eötvös József. [Google Scholar]

- Sántha, K. (2011). Abdukció a kvalitatív kutatásban. Eötvös József. [Google Scholar]

- Sántha, K., & Gyeszli, E. (2022). Abduction in teaching: Results of a qualitative research. The New Educational Review, 68, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, J. L. (2007). Experimental studies of ongoing conscious experience. In G. R. Bock, & J. Marsh (Eds.), Novartis foundation symposia (1st ed., pp. 100–122). Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soare, F. S., & Institutul de Investigare a Crimelor Comunismului și Memoria Exilului Românesc (Eds.). (2013). Politică și societate în epoca Ceaușescu. [Politics and society in the Ceausescu era]. Polirom. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart, H. (2016). Reducing the stigma of mental illness. Global Mental Health, 3, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Székely, I. (2015). Reziliencia: A rendszerelmélettől a társadalomtudományokig. Replika, 94, 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Tokić, A., Slišković, A., & Nikolić Ivanišević, M. (2023). Well-Being of parents of children with disabilities—Does employment status matter? Social Sciences, 12(8), 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. (2023). Inclusive education and long-term care: Challenges and solutions in Eastern Europe. UNICEF. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/eca/reports/focus-quality-inclusive-education (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- World Health Organization. (2022). Global report on health equity for persons with disabilities. WHO. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240063600 (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Zoja, L. (2018). The father: Historical, psychological and cultural perspectives (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfia, R. (2020). Mother’s experience in caring for children with special needs: A literature review. IJDS Indonesian Journal of Disability Studies, 7(1), 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).