The Influence of Home Language and Literacy Environment and Parental Self-Efficacy on Chilean Preschoolers’ Early Literacy Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review of the Literature

2.1. Early Literacy

2.2. Home Language and Literacy Environment and Family Literacy Programs

3. Methods

3.1. Instruments

3.1.1. Parents and Caregivers

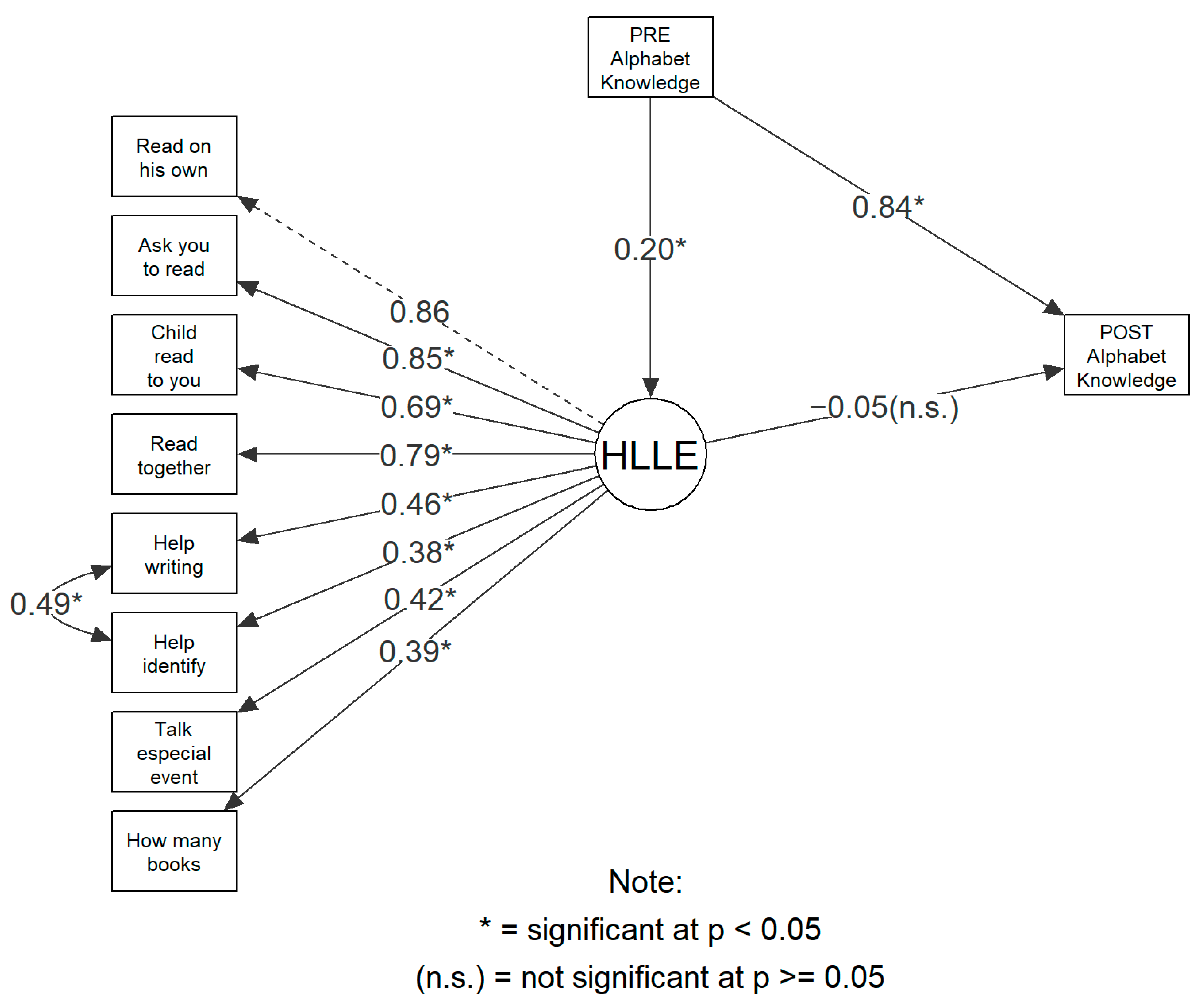

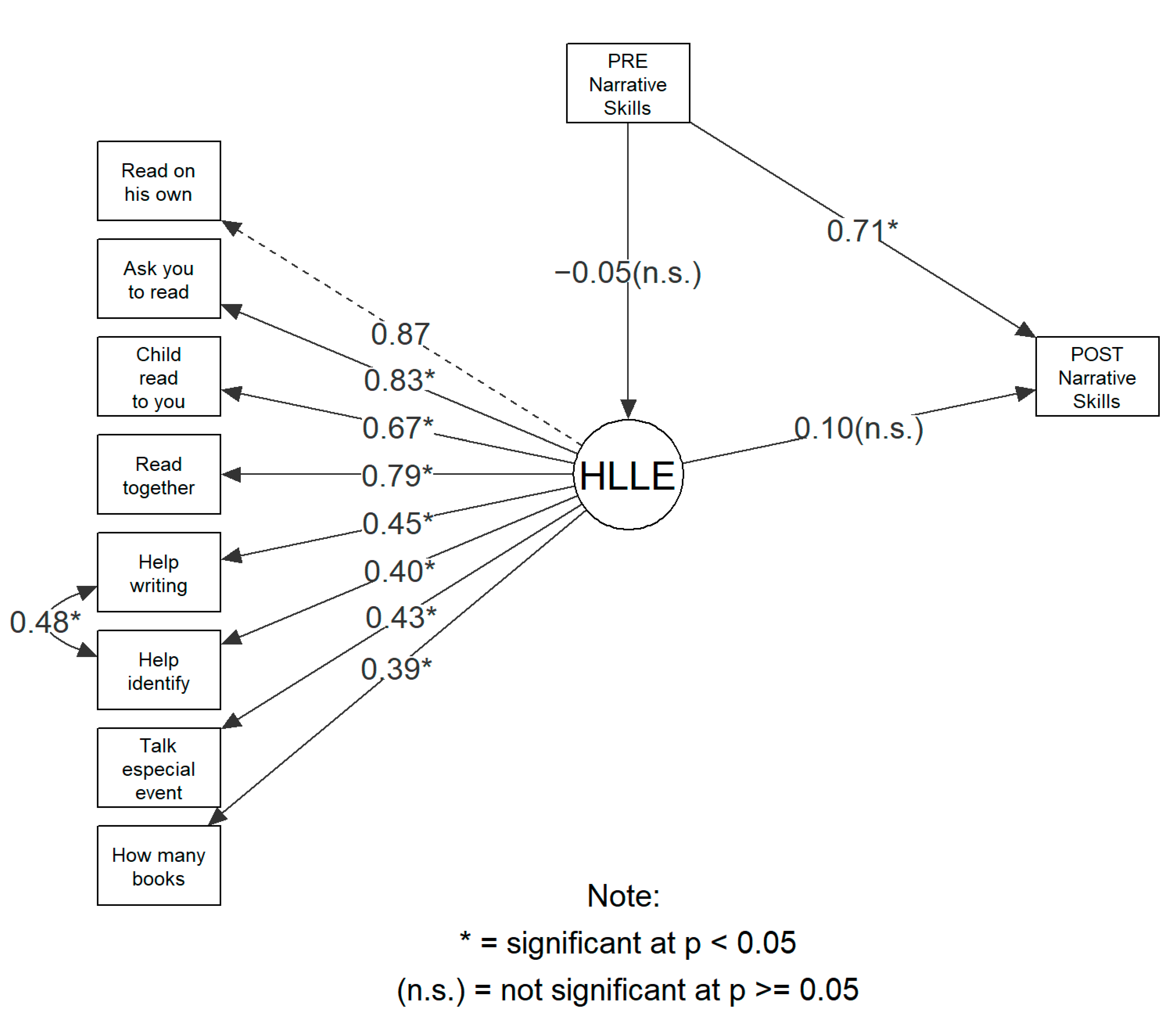

- Home Language and Literacy Environment Survey. Parents of both groups were asked to complete the HLLE before and after the intervention (Romero-Contreras, 2006). This questionnaire includes 7 questions about the frequency with which parents and children engage in literacy-related activities and one question about the number of books available at home. The tool is designed to capture home-based literacy practices and their characteristics (Mendive et al., 2020). These characteristics include activities that parents and children engage in often, such as talking about past events and asking adults to read to children, as well as the number of books at home. The structure of the tool is the following: The first four questions refer to how often children engage in reading activities alone or with an adult. The fifth question asks about the number of books at home. Two questions refer to how often adults help children write or read, and the last question refers to the frequency with which parents and children talk about special past events. Questions are formulated in a Likert scale format, with the exception of the question about the number of books. The tool has been used in Latin American studies (Costa Rica, Mexico, El Salvador) with adequate psychometric properties. Cronbach’s alpha for both applications was good: 0.82 (pre test scores) and 0.83 (post test scores). Appendix A presents a table with the pre- and post-results, including means, standard deviations, p-values, and effect sizes for each of the items in the survey.

- Compared self-efficacy survey. This is a self-reported measure that requires parents to assess how confident they felt about interacting with their children in several literacy-related activities before and after participating in the Alma project. The survey was designed by the authors using items that were related to the strategies presented in the workshops and following M. R. Sanders and Woolley (2005), who suggest that reporting parenting practices is best predicted by task-specific measures of parental self-efficacy. The instrument includes nine questions grouped into 3 dimensions. Dimension 1 refers to “preparedness” and requires participants to rate how well prepared they felt to engage in literacy-related activities such as shared reading, talking about books, sharing, playing, and helping children regulate their emotions (5 items). Dimension 2 refers to “belonging” and asks participants to rate their sense of belonging and connection with parents in the school community (2 items). Finally, dimension 3 refers to “frequency” and asks parents to report the number of times they read and played games with their children every week (2 items). For each of these dimensions, parents were asked to rate their perceptions on a 5-point Likert scale. For example, item 1 reads, “I am capable of reading a picture book with my child”, and parents can choose between “fully agree-agree-neither agree nor disagree-disagree-fully disagree”. Other items refer to being able to teach literacy elements (e.g., letters of the alphabet, print conventions), being able to talk with my child about emotions, etc. For the purposes of the current study, we did not include the items from dimensions 2 and 3 since they tap into parents’ perception of social inclusion within the school context and frequency of activities, and not into self-efficacy in a more explicit way. Parents completed this survey after participating in the last workshop session. Parents rated each dimension for “before participating in the program” and “after participating in the program”. Thus, two scores were computed for each dimension. The survey can be found in Appendix A. To compute the score for each dimension, we added the scores for each set of questions. Thus, the score for dimension 1 (preparedness) is the sum of 5 questions. Cronbach’s alpha for each dimension were: 0.78 (preparedness), 0.67 (belonging), and 0.56 (frequency). Appendix B describes validation procedures for the survey.

3.1.2. Children

- Alphabet knowledge task. Children are presented with each letter of the alphabet and are asked to give its name or sound. For each correctly identified letter (name or sound), children are given one point. The total score for this task is 27 points, and scores are interpreted using the Dialect Alphabet Task end-of-year criteria for interpretation of kindergarten scores. Because alphabet knowledge is not a required measure for Pre-kindergartners, there are no criteria for score interpretation at this level. We used the results from a previous study to interpret Pre-kindergarten students’ scores (Orellana et al., 2022a).

- Narrative skills. To assess narrative skills, we used a translated and adapted version of Paris and Paris (2003) Narrative Comprehension of Picture Books Task (NC task) by Silva et al. (2014). In this task, children are presented with a wordless picture book (A boy, a dog and a frog, by Mayer, 1967). After looking at the pictures (i.e., picture walk), children retell the story and answer comprehension questions. For the picture walk, evaluators present each illustration and introduce the story to the child, who must then observe the pictures and narrate the story. The first two questions ask children to identify characters and story setting (literal comprehension). Questions 3 and 4 require participants to infer what characters are thinking and saying and support their responses with evidence from the pictures. Questions 5 through 9 ask students to identify events and story problems and elaborate on why those events happened (inferential comprehension). Finally, question 10 focuses on the story theme and also asks students to identify the theme and support their arguments. To score students’ responses, we used Silva et al.’s (2014) rubric, where 0 points are given to children who did not respond, said they did not know the answer, or gave a response that was not related to the question being asked. One point was given to answers that identified the component in the question, and 2 points if children identified the element and elaborated on their response. Validity evidence for this rubric can be found in Orellana et al. (2022b).

3.2. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Mean | SD | Range | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participa | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Diff | p_Value | Cohen_d | n |

| Home Language and Literacy Environment—Overall | ||||||||||

| Participa | 23.157 | 26.240 | 4.885 | 3.962 | 11–32 | 15–32 | 3.083 | 0.000 | 0.687 | 121 |

| Control | 21.529 | 23.790 | 4.899 | 4.712 | 9–32 | 12–31 | 2.261 | 0.000 | 0.470 | 119 |

| Home Language and Literacy Environment—PreKinder | ||||||||||

| Participa | 22.985 | 25.561 | 4.744 | 4.329 | 12–32 | 15–32 | 2.576 | 0.000 | 0.566 | 66 |

| Control | 21.638 | 23.190 | 5.081 | 5.056 | 9–31 | 12–31 | 1.552 | 0.005 | 0.306 | 58 |

| Home Language and Literacy Environment—Kinder | ||||||||||

| Participa | 23.364 | 27.055 | 5.086 | 3.330 | 11–32 | 15–32 | 3.691 | 0.000 | 0.811 | 55 |

| Control | 21.426 | 24.361 | 4.759 | 4.324 | 10–32 | 12–31 | 2.934 | 0.000 | 0.644 | 61 |

| Mean | SD | Range | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Diff | p_Value | Cohen_d | n |

| HLLE1—How often does your child look at or read books or magazines on his or her own at home? | 2.544 | 2.950 | 0.977 | 0.878 | 1–4 | 1–4 | 0.406 | 0.000 | 0.436 | 239 |

| HLLE2—How often does your child ask you to read to him or her? | 2.556 | 3.000 | 0.998 | 0.907 | 1–4 | 1–4 | 0.444 | 0.000 | 0.464 | 239 |

| HLLE3—How often does your child read to you (or act as if reading)? | 2.594 | 3.042 | 1.020 | 0.883 | 1–4 | 1–4 | 0.448 | 0.000 | 0.468 | 239 |

| HLLE4—How often do you read books with your child at home? | 2.444 | 2.816 | 0.950 | 0.921 | 1–4 | 1–4 | 0.372 | 0.000 | 0.398 | 239 |

| HLLE5—How often do you help your child to write letters or numbers during the week? | 3.134 | 3.448 | 0.859 | 0.695 | 1–4 | 1–4 | 0.314 | 0.000 | 0.399 | 239 |

| HLLE6—How often do you help your child read or identify letters or numbers during the week? | 3.272 | 3.519 | 0.781 | 0.627 | 1–4 | 2–4 | 0.247 | 0.000 | 0.347 | 239 |

| HLLE7—How often do you and your child talk about a special past event? (for example, a birthday celebration, a party, a family outing, or a school event that occurred in the past? | 3.322 | 3.531 | 0.889 | 0.709 | 1–4 | 1–4 | 0.209 | 0.000 | 0.258 | 239 |

| HLLE8—How many children’s books do you have at home (with including school books). Write the number that applies. | 6.477 | 6.715 | 0.934 | 0.914 | 5–8 | 5–8 | 0.238 | 0.000 | 0.258 | 239 |

Appendix B. Psychometric Analysis for the Self-Efficacy Survey

| Cronbach’s Alpha | ||

|---|---|---|

| Item | Before | After |

| Total | 0.859 | 0.782 |

| 1a. How well prepared am I to read a story with my child? | 0.851 | 0.728 |

| 1b. How well prepared am I to talk about the story? | 0.822 | 0.709 |

| 1c. How well prepared am I to teach my child through play? | 0.815 | 0.710 |

| 1d. How well prepared am I to enjoy spending time together? | 0.816 | 0.756 |

| 1e. How well prepared am I to help my child regulate his/her emotions? | 0.841 | 0.797 |

| Factor 1 | |

|---|---|

| Before 1a | 0.625 |

| Before 1b | 0.737 |

| Before 1c | 0.829 |

| Before 1d | 0.795 |

| Before 1e | 0.749 |

| After 1a | 0.002 |

| After 1b | 0.064 |

| After 1c | 0.194 |

| After 1d | 0.182 |

| After 1e | 0.102 |

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Before 1a | 0.595 | 0.267 |

| Before 1b | 0.735 | 0.024 |

| Before 1c | 0.854 | −0.045 |

| Before 1d | 0.788 | 0.058 |

| Before 1e | 0.746 | 0.069 |

| After 1a | −0.083 | 0.791 |

| After 1b | −0.028 | 0.848 |

| After 1c | 0.140 | 0.681 |

| After 1d | 0.130 | 0.557 |

| After 1e | 0.064 | 0.442 |

References

- Adrian, J. E., Clemente, R. A., Villanueva, L., & Rieffe, C. (2005). Parent-child picture-book reading, mothers’ mental state language and children’s theory of mind. Journal of Child Language, 32(3), 673–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agencia de Calidad de la Educación. (2018). Informe de resultados. Estudio nacional lectura 2ª básico 2017. Agencia de Calidad de la Educación. [Google Scholar]

- Alper, R. M., Beiting, M., Luo, R., Jaen, J., Peel, M., Levi, O., Robinson, C., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2021). Change the things you can: Modifiable parent characteristics predict high-quality early language interaction withing socioeconomic status. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 64(6), 1992–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, K. L., Atkinson, T. S., Swaggerty, E. A., & O’Brien, K. (2019). Exploring the short-term impacts of a community-based book distribution program. Literacy Research and Instruction, 58(2), 84–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardelt, M., & Eccles, J. S. (2001). Effects of mothers’ parental efficacy beliefs and promotive parenting strategies on inner-city youth. J. Family Issues, 22, 944–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonk, L., Gijselaers, H. J. M., Ritzen, H., & Brand-Gruwel, S. (2018). A review of the relationship between parental involvement indicators and academic achievement. Educational Research Review, 24, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, L., Villalón, M., & Orellana, E. (2006). Diferencias en la predictividad de la lectura entre primer año y Cuarto Año Básicos. Psykhe, 15(1), 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bråten, I., & Olaussen, B. S. (2005). Profiling individual differences in student motivation: A longitudinal cluster-analytic study in different academic contexts. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 30(3), 359–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In R. M. Lerner, & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 793–828). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, S. R. (2011). Home literacy environments (HLEs) provided to very young children. Early Child Development and Care, 181(4), 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, S. R., Hecht, S. A., & Lonigan, C. J. (2002). Relations of the home literacy environment (HLE) to the development of reading-related abilities: A one-year longitudinal study. Reading Research Quarterly, 37, 408–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burris, P. W., Phillips, B. M., & Lonigan, C. J. (2019). Examining the relations of the home literacy environments of families of low SES with children’s early literacy skills. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 24(2), 154–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bus, A. G., van Ijzendoorn, M. H., & Pellegrini, A. (1995). Joint book reading makes for success in learning to read: A meta-analysis on intergenerational transmission of literacy. Review of Educational Research, 65, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, K. (2003). Text comprehension and its relation to coherence and cohesion in children’s fictional narratives. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 21(3), 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, J. M., Holliman, A. J., Weir, F., & Baroody, A. E. (2019). Literacy interest, home literacy environment and emergent literacy skills in preschoolers. Journal of Research in Reading, 42(1), 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterji, M. (2006). Reading achievement gaps, correlates, and moderators of early reading achievement: Evidence from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study (ECLS) kindergarten to first grade sample. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(3), 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosnoe, R., Leventhal, T., Wirth, R. J., Pierce, K. M., & Pianta, R. C. (2010). Family socioeconomic status and consistent environmental stimulation in early childhood. Child Development, 81, 972–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curenton, S. M. (2011). Understanding the landscapes of stories: The association between preschoolers’ narrative comprehension and production skills and cognitive abilities. Early Child Development and Care, 181(6), 791–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Calle, A. M., Guzmán-Simón, F., & García-Jiménez, E. (2018). Letter knowledge and learning sequence of graphemes in Spanish: Precursors of early reading. Revista de Psicodidáctica (English Edition), 23(2), 128–136. [Google Scholar]

- Ebert, S., Peterson, C., Slaughter, V., & Weinert, S. (2017). Links among parents’ mental state language, family socioeconomic status, and preschoolers’ theory of mind development. Cognitive Development, 44, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farver, J. A., Xu, Y., Lonigan, C. J., & Eppe, S. (2013). The home literacy environment and Latino head start children’s emergent literacy skills. Developmental Psychology, 49(4), 775–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finders, J., Wilson, E., & Duncan, R. (2023). Early childhood education language environments: Considerations for research and practice. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1202819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner-Neblett, N., & Iruka, I. U. (2015). Oral narrative skills: Explaining the language-emergent literacy link by race/ethnicity and SES. Developmental Psychology, 51(7), 889–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgiou, G. K., Inoue, T., & Parrila, R. (2021). Developmental relations between home literacy environment, reading interest, and reading skills: Evidence from a 3-year longitudinal study. Child Development, 92(5), 2053–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoff, E. (2003). The specificity of environmental influence: Socioeconomic status affects early vocabulary development via maternal speech. Child Development, 74(5), 1368–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutton, J. S., Dudley, J., Horowitz-Kraus, T., DeWitt, T., & Holland, S. K. (2020). Associations between home literacy environment, brain white matter integrity and cognitive abilities in preschool-age children. Acta Paediatrica, 109, 1376–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C., Clark, S., & Reutzel, D. (2013). Enhancing alphabet knowledge instruction: Research implications and practical strategies for early childhood educators. Early Childhood Education Journal, 41, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juel, C. (1988). Learning to read and write: A longitudinal study of 54 children from first through fourth grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(4), 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justice, L. M., Bowles, R. P., Kaderavek, J. N., Ukrainetz, T. A., Eisenberg, S. L., & Gillam, R. B. (2006). The index of narrative microstructure: A clinical tool for analyzing school-age children’s narrative performances. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 15(2), 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Košutar, S., Kramarić, M., & Hržica, G. (2022). The relationship between narrative microstructure and macrostructure: Differences between six-and eight-year-olds. Psychology of Language and Communication, 26(1), 126–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppänen, U., Aunola, K., Niemi, P., & Nurmy, J.-E. (2008). Letter knowledge predicts grade 4 reading fluency and reading comprehension. Learning and Instruction, 18(6), 548–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva, D., & Smith, M. (2016). Beyond book reading: Narrative participation styles in family reminiscing predict children’s print knowledge in low-income Chilean families. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 37, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, J. A. R., Justice, L. M., Yumus, M., & Chaparro-Moreno, L. J. (2020). When children are not read to at home: The million word gap. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 40(5), 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R., Pace, A., Levine, D., Iglesias, A., de Villiers, J., Golinkoff, R. M., Wilson, M. S., & Hirsch-Pasek, K. (2021). Home literacy environment and existing knowledge mediate the link between socioeconomic status and language learning skills in dual language learners. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 55, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manu, A., Ewerling, F., Barros, A. J., & Victora, C. G. (2018). Association between availability of children’s book and the literacy-numeracy skills of children aged 36 to 59 months: Secondary analysis of the UNICEF Multiple-Indicator Cluster Surveys covering 35 countries. Journal of Global Health, 9(1), 010403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Masarik, A. S., & Conger, R. D. (2017). Stress and child development: A review of the family stress model. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, M. (1967). A boy, a dog, and a frog. Dial Press. [Google Scholar]

- McKeough, A., Genereux, R., & Jeary, J. (2006). Structure, content, and language usage: How do exceptional and average storywriters differ? High Ability Studies, 17, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, S., Leech, K. A., Corriveau, K. H., & Daly, M. (2023). Indirect effects of early shared reading and access to books on reading vocabulary in middle childhood. Scientific Studies of Reading, 28(1), 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendive, S., Mascareño Lara, M., Aldoney, D., Pérez, J. C., & Pezoa, J. P. (2020). Home language and literacy environments and early literacy trajectories of low-socioeconomic status chilean children. Child Development, 91(6), 2042–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, S. E., & Bus, A. G. (2011). To read or not to read: A meta-analysis of print exposure from infancy to early adulthood. Psychological Bulletin, 137(2), 267–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, S., Vagh, S. B., Dulay, K. M., Snowling, M., Donolato, E., & Melby-Lervåg, M. (2024). Home learning environments and children’s language and literacy skills: A meta-analytic review of studies conducted in low-and middle-income countries. Psychological Bulletin, 150(2), 132–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niklas, F., Wirth, A., Guffler, S., Drescher, N., & Ehmig, S. C. (2020). The home literacy environment as a mediator between parental attitudes toward shared reading and children’s linguistic competencies. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nippold, M. A., & Schwartz, I. E. (1996). Children with slow expressive language development: What is the forecast for school achievement? American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 5(2), 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Fallon, M. K., Alper, R. M., Beiting, M., & Luo, R. (2022). Quantity and quality of early reading (O’Fallon et al., 2022). ASHA Journals. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppermann, E., Cohen, F., Wolf, K., Burghardt, L., & Anders, Y. (2021). Changes in parents’ home learning activities with their children during the COVID-19 lockdown—The role of parental stress, parents’ self-efficacy and social support. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 682540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, P., & Pezoa, J. P. (2021). Interpretación edumétrica de los resultados del test EVOC de vocabulario en español. ESE. Estudios Sobre Educación, 40, 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, P., Valenzuela, M. F., Villalón, M., & Rosati, M. (2022a). Efectos del apoyo al ambiente familiar en lenguaje y la alfabetización de niños de 4 a 6 años en contextos desfavorecidos. Revista Interdisciplinaria, 39, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, P., Valenzuela Hasenohr, M. F., Pezoa, J., & Villalón, M. (2022b). Competencia narrativa: Evidencias de validez para la estandarización de su evaluación en niños chilenos. Psykhe (Santiago), 31(2), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, A. H., & Paris, S. G. (2003). Assessing narrative comprehension in young children. Reading Research Quarterly, 38(1), 36–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, D. B., Tonn, P., Spencer, T. D., & Foster, M. E. (2020). The classification accuracy of a dynamic assessment of inferential word learning for bilingual English/Spanish-speaking school-age children. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 51(1), 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, B. M., Piasta, S. B., Anthony, J. L., Lonigan, C. J., & Francis, D. J. (2012). IRTs of the ABCs: Children’s letter name acquisition. Journal of School Psychology, 50(4), 461–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Phillips, B. M., & Lonigan, C. J. (2009). Variations in the home literacy environment of preschool children: A cluster analytic approach. Scientific Studies of Reading, 13(2), 146–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piasta, S. B., Groom, L. J., Khan, K. S., Skibbe, L. E., & Bowles, R. P. (2018). Young children’s narrative skill: Concurrent and predictive associations with emergent literacy and early word reading skills. Reading & Writing, 31, 1479–1498. [Google Scholar]

- Piasta, S. B., Logan, J. A. R., Farley, K. R., Strang, T. M., & Justice, L. M. (2022). Profiles and predictors of children’s growth in alphabet knowledge. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk (JESPAR), 27(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasta, S. B., & Wagner, R. K. (2010). Developing emergent literacy skills: A meta-analysis of alphabet learning and instruction. Reading Research Quarterly, 45(1), 8–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, C. P., Silverman, R. D., Harring, J. R., & Montecillo, C. (2010). The role of vocabulary depth in predicting reading comprehension among English monolingual and Spanish–English bilingual children in elementary school. Reading and Writing, 25, 1635–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relyea, J. E., Zhang, J., Liu, Y., & Lopez Wui, M. G. (2019). Contribution of home language and literacy environment to English reading comprehension for emergent bilinguals: Sequential mediation model analyses. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(3), 473–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robins, S., Ghosh, D., Rosales, N., & Treiman, R. (2014). Letter knowledge in parent–child conversations: Differences between families differing in socio-economic status. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Contreras, S. (2006). Measuring language and literacy-related practices in low-SES Costa Rican families: Research instruments and results [Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University]. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R. M., Fauth, R. C., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2006). Childhood poverty: Implications for school readiness and early childhood education. In B. Spodek, & O. N. Saracho (Eds.), Handbook of research on the education of young children (pp. 323–346). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Sabourin-Guardo, E., Miljkovitch, R., Bernier, A., Cyr, C., St-Laurent, D., & Dubois-Comtois, K. (2022). Longitudinal associations between the quality of family interactions and school-age children’s narrative abilities in the context of financial insecurity. Family Process, 63(3), 1574–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, M. R., & Woolley, M. L. (2005). The relationship between maternal self-efficacy and parenting practices: Implications for parent training. Child: Care, Health and Development, 31(1), 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, T. J. M., & Pander Maat, H. L. W. (2006). Cohesion and Coherence. In K. Brown (Ed.), Encyclopedia of language and linguistics (Volume 2, pp. 591–595). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Schatschneider, C., Fletcher, J. M., Francis, D. J., Carlson, C. D., & Foorman, B. R. (2004). Kindergarten prediction of reading skills: A longitudinal comparative analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(2), 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sénéchal, M. (2006). Testing the home literacy model: Parent involvement in kindergarten is differentially related to grade 4 reading comprehension, fluency, spelling, and reading for pleasure. Scientific Studies of Reading, 10, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sénéchal, M., & LeFevre, J. (2003). Parental involvement in the development of children’s reading skills: A five-year longitudinal study. Child Development, 73, 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sénéchal, M., Whissell, J., & Bildfell, A. (2017). Starting from home: Home literacy practices that make a difference. In Theories of reading development (pp. 383–408). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, L. R., Carroll, J. M., & Solity, J. (2013). Separating the influences of prereading skills on early word and nonword reading. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 116(2), 278–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, L. R., & Hudson, J. A. (1991). Tell me a make-believe story: Coherence and cohesion in young children’s picture-elicited narratives. Developmental Psychology, 27(6), 960–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silinskas, G., Torppa, M., Lerkkanen, M.-K., & Nurmi, J.-E. (2020). The home literacy model in a highly transpar-ent orthography. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 31, 80–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M., Strasser, K., & Cain, K. (2014). Early narrative skills in Chilean preschool: Questions scaffold the production of coherent narratives. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skibbe, L. E., Justice, L. M., Zucker, T. A., & McGinty, A. S. (2008). Relations among maternal literacy beliefs, home literacy practices and the emergent literacy skills of preschoolers with specific language impairment. Early Education and Development, 19, 68–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, C. E. (1983). Literacy and language: Relationships during the preschool years. Harvard Educational Review, 55, 165–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, C. E., Burns, M. S., & Griffin, P. (1998). Preventing reading difficulties in young children. National Academy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Snow, C. E., & Dickinson, D. K. (1991). Skills that aren’t basic in a new conception of literacy. In A. Purves, & E. Jennings (Eds.), Literate systems and individual lives: Perspectives on literacy and schooling. State University of New York (SUNY) Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stanovich, K. E. (2008). Matthew effects in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. The Journal of Education, 189(1/2), 23–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storch, S. A., & Whitehurst, G. J. (2002). Oral language and code-related precursors to reading: Evidence from a longitudinal structural model. Developmental Psychology, 38(6), 934–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, K., & Lissi, M. R. (2009). Home and instruction effects on emergent literacy in a sample of Chilean kindergarten children. Scientific Studies of Reading, 13, 175–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sucena, A., Garrido, C., Marques, C., & Lousada, M. (2023). Early predictors of reading success in first grade. Frontiers in Psychology 14, 1140823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompkins, V. (2022). Relations between the home literacy environment and young children’s theory of mind. Cognitive Development, 62, 101179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uccelli, P. (2014). Aprendiendo a narrar en español: Interrrelaciones entre destrezas gramaticales y discursivas en la expresión de la temporalidad entre los 2 y los 3 años de edad. In R. Barriga Villanueva (Ed.), Las narrativas y su impacto en el desarrollo lingüístico infantil (pp. 77–110). El Colegio de México, Centro de Estudios Linguísticos y Literarios. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela-Hasenohr, F., Villalón-Bravo, M., & Orellana-García, P. (2024). Calidad de las interacciones en la lectura de cuentos en el hogar. Estudios Sobre Educación. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernon-Feagans, L., Bratsch-Hines, M., Reynolds, E., & Willoughby, M. (2020). How early maternal language input varies by race and education and predicts later child language. Child Development, 91(4), 1098–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimer, A. A., & Guajardo, N. R. (2005). False belief, emotion understanding, and social skills among head start and non-head start children. Early Education and Development, 16(3), 341–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehurst, G. J., & Lonigan, C. J. (1998). Child development and emergent literacy. Child Development, 69(3), 848–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, A., Ehmig, S. C., & Niklas, F. (2022). The role of the Home Literacy Environment for children’s linguistic and socioemotional competencies development in the early years. Social Development, 31, 372–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. Z., Inoue, T., Shu, H., & Georgiou, G. K. (2020). How does home literacy environment influence reading comprehension in Chinese? Evidence from a 3-year longitudinal study. Reading & Writing, 33, 1745–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Treatment | Control | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N Prekindergarten | 66 | 58 | 124 | ||

| Gender | M | F | M | F | |

| 26 | 40 | 26 | 32 | ||

| Mean age | 4.6 | 4.7 | |||

| N Kindergarten | 55 | 61 | 116 | ||

| Gender | M | F | M | F | |

| 32 | 23 | 32 | 29 | ||

| Mean age | 5.6 | 5.6 | |||

| Total | 121 | 119 | 240 | ||

| Mean | SD | Range | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Diff | p_Value | Cohen_d | n | |

| Alphabet Knowledge | ||||||||||

| Treatment | 5.621 | 11.052 | 5.400 | 7.453 | 0–22 | 0–27 | 5.431 | 0.000 * | 0.761 | 116 |

| Control | 4.964 | 8.627 | 5.823 | 7.595 | 0–25 | 0–27 | 3.664 | 0.000 * | 0.472 | 110 |

| Narrative Skills | ||||||||||

| Treatment | 8.457 | 11.603 | 3.875 | 3.393 | 0–17 | 5–20 | 3.147 | 0.000 * | 0.857 | 116 |

| Control | 8.145 | 10.673 | 3.993 | 3.373 | 0–19 | 0–17 | 2.527 | 0.000 * | 0.679 | 110 |

| Mean | SD | Range | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Diff | p_Value | Cohen_d | n | |

| Alphabet Knowledge—PreKinder | ||||||||||

| Treatment | 5.982 | 11.655 | 5.880 | 7.778 | 0–22 | 0–27 | 5.673 | 0.000 | 0.757 | 55 |

| Control | 4.678 | 8.627 | 5.469 | 7.976 | 0–23 | 0–27 | 3.949 | 0.000 | 0.466 | 59 |

| Alphabet Knowledge—Kinder | ||||||||||

| Treatment | 5.295 | 10.508 | 4.954 | 7.169 | 0–22 | 1–27 | 5.213 | 0.000 | 0.765 | 61 |

| Control | 5.294 | 8.627 | 6.246 | 7.208 | 0–25 | 0–26 | 3.333 | 0.000 | 0.462 | 51 |

| Narrative Skills—PreKinder | ||||||||||

| Treatment | 8.782 | 11.982 | 3.872 | 2.890 | 0–17 | 5–19 | 3.200 | 0.000 | 0.912 | 55 |

| Control | 8.288 | 11.000 | 3.939 | 3.543 | 0–17 | 3–17 | 2.712 | 0.000 | 0.721 | 59 |

| Narrative Skills—Kinder | ||||||||||

| Treatment | 8.164 | 11.262 | 3.887 | 3.781 | 1–17 | 5–20 | 3.098 | 0.000 | 0.808 | 61 |

| Control | 7.980 | 10.294 | 4.087 | 3.158 | 1–19 | 0–17 | 2.314 | 0.000 | 0.628 | 51 |

| Mean | SD | Range | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | Diff | p_Value | Cohen_d | n |

| How well prepared am I to read a story with my child? | ||||||||||

| PreKinder | 2.720 | 8.620 | 1.107 | 0.753 | 1–5 | 6–9 | 5.900 | 0.000 | 6.155 | 50 |

| Kinder | 2.652 | 8.609 | 0.948 | 0.774 | 1–5 | 6–9 | 5.957 | 0.000 | 6.855 | 46 |

| How well prepared am I to talk about the story? | ||||||||||

| PreKinder | 2.620 | 8.700 | 1.123 | 0.614 | 1–5 | 6–9 | 6.080 | 0.000 | 6.642 | 50 |

| Kinder | 2.761 | 8.717 | 1.158 | 0.544 | 1–5 | 7–9 | 5.957 | 0.000 | 6.498 | 46 |

| How well prepared am I to teach my children through play? | ||||||||||

| PreKinder | 2.740 | 8.740 | 1.306 | 0.565 | 1–5 | 7–9 | 6.000 | 0.000 | 5.819 | 50 |

| Kinder | 2.804 | 8.696 | 1.185 | 0.628 | 1–5 | 6–9 | 5.891 | 0.000 | 6.067 | 46 |

| How well prepared am I to enjoy spending time together? | ||||||||||

| PreKinder | 3.400 | 8.780 | 1.212 | 0.507 | 1–5 | 7–9 | 5.380 | 0.000 | 5.537 | 50 |

| Kinder | 3.587 | 8.957 | 1.166 | 0.206 | 1–5 | 8–9 | 5.370 | 0.000 | 5.942 | 46 |

| How well prepared am I to help my child regulate his/her emotions? | ||||||||||

| PreKinder | 3.100 | 8.500 | 1.389 | 0.814 | 1–5 | 6–9 | 5.400 | 0.000 | 4.682 | 50 |

| Kinder | 2.891 | 8.543 | 1.159 | 0.622 | 1–5 | 7–9 | 5.652 | 0.000 | 5.774 | 46 |

| Mean | SD | Range | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Diff | p_Value | Cohen_d | n | |

| Home Language and Literacy Environment—Overall | ||||||||||

| Control | 23.017 | 25.941 | 4.641 | 3.863 | 11–32 | 15–32 | 2.924 | 0.000 | 0.677 | 119 |

| Treatment | 21.694 | 24.124 | 5.170 | 4.920 | 9–32 | 12–32 | 2.430 | 0.000 | 0.481 | 121 |

| Home Language and Literacy Environment—PreKinder | ||||||||||

| Control | 22.603 | 25.948 | 4.515 | 3.476 | 11–32 | 16–32 | 3.345 | 0.000 | 0.824 | 58 |

| Treatment | 22.091 | 23.697 | 5.363 | 5.375 | 9–32 | 12–32 | 1.606 | 0.014 | 0.299 | 66 |

| Home Language and Literacy Environment—Kinder | ||||||||||

| Control | 23.410 | 25.934 | 4.762 | 4.226 | 13–32 | 15–32 | 2.525 | 0.000 | 0.554 | 61 |

| Treatment | 21.218 | 24.636 | 4.935 | 4.305 | 10–31 | 13–32 | 3.418 | 0.000 | 0.735 | 55 |

| Model Fit Statistics | Alphabet Knowledge | Narrative Skills | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 0.937 | 0.930 | |

| Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) | 0.914 | 0.904 | |

| RMSEA (90% CI) | 0.092 (0.06–012) | 0.09 (0.06–0.12) | |

| SRMR | 0.078 | 0.077 | |

| Path Coefficients (Standardized estimates) | |||

| pre intervention → post intervention (c) | 0.840 (p < 0.001) | 0.713 (p < 0.001) | |

| HLLEPRE → post intervention (b) | −0.048 (p = 0.116) | 0.099 (p = 0.142) | |

| pre intervention → HLLEPRE (a) | 0.200 (p = 0.039) | −0.045 (p = 0.638) | |

| Indirect Effect (ab) | −0.011 (p = 0.426) | −0.004 (p = 0.654) | |

| Total Effect (Total) | 0.830 (p < 0.001) | 0.709 (p < 0.001) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Orellana, P.; Cockerill, M.; Valenzuela, M.F.; Villalón, M.; De la Maza, C.; Inostroza, P. The Influence of Home Language and Literacy Environment and Parental Self-Efficacy on Chilean Preschoolers’ Early Literacy Outcomes. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 668. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060668

Orellana P, Cockerill M, Valenzuela MF, Villalón M, De la Maza C, Inostroza P. The Influence of Home Language and Literacy Environment and Parental Self-Efficacy on Chilean Preschoolers’ Early Literacy Outcomes. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(6):668. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060668

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrellana, Pelusa, Maria Cockerill, Maria Francisca Valenzuela, Malva Villalón, Carmen De la Maza, and Pamela Inostroza. 2025. "The Influence of Home Language and Literacy Environment and Parental Self-Efficacy on Chilean Preschoolers’ Early Literacy Outcomes" Education Sciences 15, no. 6: 668. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060668

APA StyleOrellana, P., Cockerill, M., Valenzuela, M. F., Villalón, M., De la Maza, C., & Inostroza, P. (2025). The Influence of Home Language and Literacy Environment and Parental Self-Efficacy on Chilean Preschoolers’ Early Literacy Outcomes. Education Sciences, 15(6), 668. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060668