Abstract

Over the past decade there has been growing interest in the identification of core practices and their incorporation into teacher-training programmes. Researchers have made use of methodological approaches based on consultation with experts and, to a lesser degree, field or empirical studies. With the aim of characterising research on core practices, we conducted a review of the recent scientific literature, identifying conceptualisations and methodological approaches. We examined 39 scientific articles published between 2019 and 2023 and identified five underlying conceptual dimensions: teachability, teacher performance, ambitious teaching, improvement of student performance, and research-based support. The most common methodological approaches used consisted of descriptive qualitative case studies conducted in the context of teacher-training programmes. We discuss how these findings could influence the use of empirical methods to identify core practices in more recently emerging fields of application, such as early childhood teacher education.

1. Introduction

One of the most challenging aspects of teacher training is the relationship between theory and practice (Darling-Hammond, 2017; Grossman & McDonald, 2008). There are a number of training models that promote the integration of pedagogical theory and practice (Clarà, 2019), one of which is the core practices model (Chan, 2023; Grossman & McDonald, 2008; Grossman et al., 2009a). The model’s fundamental proposal is the teaching of certain key skills and strategies—referred to as core practices—that teachers are able to master during the course of their training and which enable them to meaningfully influence the achievements of their students (Barahona & Davin, 2021).

Core practice aims to integrate the practical aspect of teacher training, which has been gradually consolidated, including faculties of education around the world; in the USA, it forms the core practice consortium, integrated by Stanford University, University of Pennsylvania, University of Michigan (Barahona & Davin, 2021); in addition, it has expanded to Europe, including the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (Fogo, 2014), through The University of Hong Kong (Cuenca, 2021), and in Latin America, through the Universidad Catholica of Chile.

Core practices in the context of teacher training have become established as a phenomenon of interest and are addressed by three lines of investigation. The first concerns the identification of core practices specific to teaching the various subject matters, such as English as a foreign language (Kloser, 2014), history (Windschitl et al., 2012), social sciences (Millican & Forrester, 2018), natural sciences (Grosser-Clarkson & Neel, 2020; O’Flaherty et al., 2024) and music (Kumar, 2020) The second addresses the incorporation of core practices into teacher-training programmes (Chan, 2023; Forzani, 2014; Zeichner, 2012), and the third focuses on the evaluation of training programmes involving this training approach (López-Jiménez et al., 2021).

Core practices are defined as identifiable teaching actions, sets of moves and routines that pre-service teachers are able to grasp by means of training (Barahona & Davin, 2021; Kloser, 2014; Millican & Forrester, 2018); these practices are central to the daily work of teaching and supporting student learning, and are fundamental to developing other more complex practices (Bogatić & Jevtić, 2025). Although the criteria specified for identification of core practices vary from author to author, practices have been widely incorporated into training programmes over the past decade, suggesting a drive to establish stronger ties between pre-service teachers and teaching practice.

The literature highlights specific core practices as relevant to certain subject matters, and a variety of approaches are used in their identification, such as validation by experts as part of the Delphi method (Grosser-Clarkson & Neel, 2020; Kumar, 2020; Windschitl et al., 2012) and literature review (O’Flaherty et al., 2024). However, this approach overlooks some of the criteria proposed by (Grossman et al., 2009a) and (López-Jiménez, 2023), who define core practices as (a) practices considered to be frequently occurring in certain populations of teachers, (b) practices that influence student learning, and (c) practices that can be enacted in a range of educational settings. Consultation with experts and documentary review should be accompanied by empirical studies that identify core practices using these criteria prior to their incorporation into teacher-training programmes (Grossman et al., 2009b).

The core practices model allows us not only to identify those practices that are central to a given subject matter, but also to provide future teachers with more robust practical training in more specific and emerging fields of application, such as early childhood teacher education (López-Jiménez et al., 2021). However, there is currently little evidence available concerning the identification and incorporation of core practices into early childhood teacher education (Hedges & Cooper, 2018; López-Jiménez, 2023; McDonald et al., 2013). Thus, we adopt a theoretical framework that allows us to identify and understand the grammar of early childhood education pedagogical practice, that is, to identify the key actions or routines early childhood teacher education teachers learn during their training, deciphering their constituent parts, fostering the existence of a common language and a repertoire of practices that can be transferred across different educational contexts (Hedges & Cooper, 2018; López-Jiménez et al., 2021; López-Jiménez, 2023) as teaching has its own very specific requirements and challenges. and requires a common language and a structure to describe it (Matsumoto-Royo & Conget, 2024).

The purpose of this article was to characterise the study of core practices in initial teacher education based on a review of recent scientific research, identifying their conceptualizations and predominant methodological approaches. To this end, we asked: How are core practices conceptualised in recent research? What core practices have been empirically investigated? And what methodological approaches have been used? It is hoped that a review of this type will help guide the incorporation of core practices into training programmes for early childhood educators.

Theoretical Framework

This study is based on Grossman’s postulates on core practices, understood as a set of strategies and actions that define the teaching profession and structure learning and instruction in teacher education. From this perspective, teacher-training programmes formally incorporate instances of representation, decomposition, and approximation, both in coursework and practical settings, ensuring comprehensive training.

We adopt these postulates (Barahona & Davin, 2021; Grossman et al., 2009a, 2009b) to conceptualise core practices as identifiable actions, movements, and teaching routines that trainee teachers can recognise and develop during their training. We characterise these practices as follows (Barahona & Davin, 2021; Matsumoto-Royo & Conget, 2024):

- (a)

- They frequently occur in teaching practice.

- (b)

- They are supported by research and have the potential to improve student achievement.

- (c)

- They can be understood and applied by pre-service teachers.

- (d)

- They preserve the integrity and complexity of teaching.

- (e)

- They can be effectively implemented in specific classroom settings.

These characteristics have emerged from the field of teacher training through a perspective known as practice-based pedagogy, which emphasises that teacher education should focus on the key actions and strategies that teachers employ in their profession (Owens et al., 2021). Another crucial aspect of this approach is that training should take place within communities of practice—collaborative spaces involving teachers, pre-service teachers, and teacher educators—aimed at fostering relationships that support learning about teaching practice.

According to (Grossman et al., 2009b), this theoretical approach has helped to differentiate core practices from previous similar proposals (e.g., competences) by addressing the interactive and pedagogical components of teaching practice. In other words, core practices are not standardised actions, but a framework of essential practices that form the basis of a common language for research and teacher training (Grossman & McDonald, 2008; Owens et al., 2021).

Within this theoretical perspective, a few models have proposed sets of core practices for teacher training. For example, the University of Michigan proposed 19 core practices, termed high-leverage practices (Matsumoto-Royo & Conget, 2024), while the University of Washington proposed nine core practices (Kavanagh et al., 2020). The teaching methodology of these practices involves three elements that teacher educators must ensure: representation, decomposition and approximation of the practice (Grossman et al., 2009a; Owens et al., 2021; Bogatić & Jevtić, 2025). Representation refers to all the ways in which the practice is presented to novices (real models, videos or written records, etc.). Decomposition refers to a common language that allows novices to describe the practice in segments and the approach to the implementation (rehearsals, simulations of the task).

Another line of research concerns the identification of core practices and their subsequent incorporation into training programmes. These studies pinpoint core practices that are specifically related to the various subject matters by means of consultation with experts (Grosser-Clarkson & Neel, 2020; Kumar, 2020; Windschitl et al., 2012) and review of the specialised literature (Millican & Forrester, 2018; O’Flaherty et al., 2024). A further line of research concerning the definition of core practices is the empirical study of those enacted by expert teachers in their classrooms (Tricco et al., 2018).

2. Materials and Methods

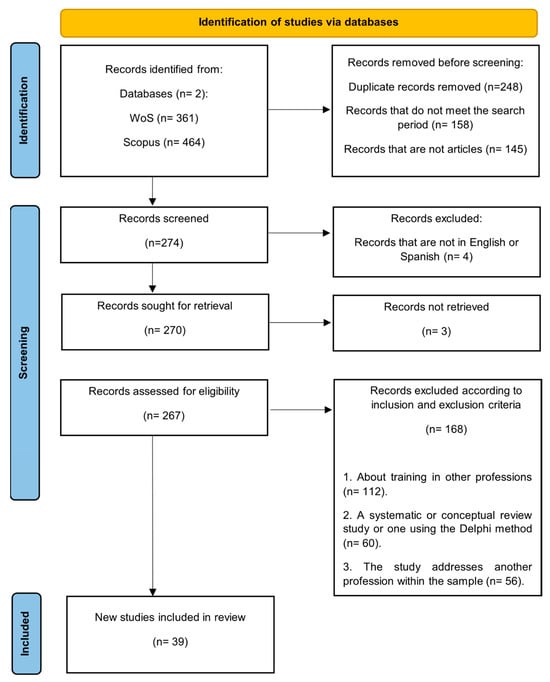

For the present study, we selected the systematic literature review method (Huanca-Arohuanca, 2022) and used the PRISMA guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses), which provide a systematic and structured approach to conducting literature reviews. This model is utilised to improve the transparency and quality of studies by establishing clear guidelines for the identification, selection, evaluation, and synthesis of the available scientific evidence (Guirao, 2015; Newman & Gough, 2020). Following these guidelines, a protocol was developed to plan the review and analysis process, which followed five stages: (1) definition of research objectives; (2) search process; (3) definition of inclusion and exclusion criteria; (4) data selection and extraction process; and (5) data analysis.

- Phase 1: Research objectives

To analyse the papers dealing with core practices published in the last 5 years, three research objectives were set (1) to examine the conceptual foundations on which current core practice research is based; (2) to identify which core practices have been studied empirically; and (3) to explore the methodological approaches used in the empirical studies. These objectives provide an overview of the understanding and methodological approaches used in the empirical study of core practices in teacher education.

- Phase 2: Search Process

This review focused on peer-reviewed scientific studies published in high-impact journals and available online, searching for articles in two databases: Web of Science (WoS) and SCOPUS. These databases were selected for their rigor and comprehensiveness, integrating all relevant sources for basic and applied research (Assarroudi et al., 2018). To identify potentially eligible studies, sets of keywords were defined to carry out the article search process rigorously. The following Boolean terms were used: (“Core practice” OR “practice based” OR “practice-based” (All Fields)) AND (“early childhood education” OR “preschool education” OR “teacher education” OR “initial teacher education “OR “preservice teacher” (All Fields)).

Titles, keywords and abstracts of the articles published between 1 January 2019 and 1 May 2023 were defined as search criteria. This approach was taken in order to answer the research questions based on recent evidence. The search was conducted in May 2023, covering a five-year period that includes the most recent advances and emerging trends in the field, ensuring this review is both relevant and timely (Creswell, 2014). This strategy enabled us to map the conceptualisation and methodological approach of core practices during this period (Roller & Lavrakas, 2015).

- Phase 3: Definition of Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

After conducting the search, 825 studies were identified. Relevant information for each article, including authors, title, keywords, abstract, Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs), year, and journal of publication, was recorded in an Excel database. Two researchers manually reviewed this database to identify duplicates, resulting in the exclusion of 248 studies due to duplication, and leaving 557 studies for further analysis.

Subsequently, those studies that did not meet the time range for publication were eliminated, excluding 158 documents. Then, 145 studies that did not meet the criteria of being articles were excluded, leaving a total of 274 investigations. After a manual review of the language of these articles, 4 were eliminated if they did not meet the criteria of being in Spanish or English, resulting in 270 articles for analysis based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were established to ensure that the selected studies articles aligned with this review’s objectives and scope. The inclusion criteria ensured relevance to this review’s focus, while the exclusion criteria discarded studies that did not meet strict methodological standards or addressed topics outside the field of interest. Table 1 presents the inclusion and exclusion criteria applied to the abstracts: (a) the reported study should be framed in the area of teacher training in the study area of core practices; (b) the study should be empirical, emphasising data collection through verifiable methods such as observation or direct experimentation; (c) the study should incorporate a sample of participants from the education area composed of pre-service teacher, teacher in service or teacher educators.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

- Phase 4: Data Selection and Extraction Process

A comprehensive evaluation of the articles was conducted by reading their titles, keywords, and abstracts. Five researchers rigorously and independently applied the predefined set of inclusion and exclusion criteria, scoring each article. Articles requiring collective decisions were reviewed in group meetings. This review is presented in Figure 1, which schematises the selection process carried out.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of search and selection process according to the PRISMA guidelines.

We excluded 56 articles from the participants’ category because the participants identified in the methodological frameworks did not refer to the participation of in-service teachers, pre-service teachers or teacher educators.

In relation to the study type category, 60 articles were excluded because they did not meet the characteristics of an empirical study. Regarding the subject category, 112 articles were excluded on the grounds that they did not fall within the area of core practices in teacher training or the teaching process in early childhood education.

A total of 39 articles (see Appendix A) met the inclusion criteria and were therefore considered relevant for this review. Three articles that could not be accessed electronically were discarded.

- Phase 5: Data analysis

The 39 selected articles (see Appendix A) were subjected to a qualitative content analysis approach through a systematic sorting process to identify categories and themes that responded to the research questions (Xie et al., 2020). To meet the objectives of this review, pre-established categories were defined: conceptualisation of core practices, core practice investigated, research design and operationalisation of core practices explored. The data were organised into codes and emerging subcategories (see Table 2), except for the predefined subcategories in research design, based on the typology of Johnson and Mawyer (2019). This study understands ‘operationalisation of a given Core Practice’ as the explicit definition of steps or actions followed to observe, apprehend or measure the core practice precisely.

Table 2.

Categories and subcategories of analysis.

A total of six researchers participated in this study, organised in pairs to ensure the reliability of the analysis. Initially, tables were created for each publication, comprising sections of the texts that responded to the categories that were formulated. Subsequently, the data were organised, reconstructed and managed into codes and subcategories, allowing for a more in-depth analysis (Colonnese et al., 2022). Regarding criteria (a) and (b), the terms and conceptualisations that were stated by the authors in the articles were respected. Nevertheless, seven articles employed (Johnson & Mawyer, 2019) typology to infer the research design, while the second criterion categorised the research purposes into three categories proposed by the same author: descriptive/exploratory, correlational/associative. In both instances, categorisation was agreed upon by two members of the research team. Prior to the presentation of the results, the subcategories were subjected to a comprehensive review by the entire research team. This entailed an in-depth discussion concerning their relevance, coherence, and the most appropriate designation.

3. Results

The results from the 39 articles analysed are presented in three sections that respond to the questions that guided this review. The first section presents the conceptual diversity and nuances of recent research on the conceptualisation of core practices. The second section presents the specific core practices that have been empirically studied, and the final section describes the methodological approaches identified in the study of core practices.

3.1. Definition and Conceptualisation of Core Practices in Recent Literature

Regarding how core practices are conceptualised by recent publications on the subject, of the 39 articles analysed, 18 articles [1, 2, 3, 6, 8, 10, 13, 14, 15, 18, 19, 28, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36] (Appendix A) allude to or mention the term without providing an explicit definition, while 21 present a precise definition of core practices [4, 5, 7, 9, 11, 12, 16, 17, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 29, 30, 37, 38, 39] (Appendix A). One set of definitions is similar in that they mainly conceptualise CPs as teaching practices, while another set of definitions emphasise their theoretical relevance for educational theory and practice.

3.1.1. Core Practices as Teaching Practices

The following dimensions of core practices as teaching practices are emphasised in this set of definitions: their teachability in teacher education, their relevance to teacher performance, and their research-based support.

Firstly, seven articles [17, 22, 26, 30, 37, 38, 39] (Appendix A) conceptualise core practices as identifiable elements of teaching (movements, strategies, skills, routines) that are fundamental to supporting learning and improving student performance. These components can be elucidated, apprehended and enacted by in-service teachers and pre-service teachers, as well as taught by teacher educators through successive practical approaches. In this context, the definitions place an emphasis on the teachable and learnable aspects of core practices for initial teacher education. To illustrate, the study by Cash et al. (2022), which examined the learning and performance of a set of core practices in a sample of pre-service physical education teachers, defines them as follows:

Core practices represent a precisely defined set of outcomes for teachers to acquire (Grossman et al., 2009a). Core practices (a) can be demonstrably taught to PSTs (Pre-service teachers); (b) have a strong alignment between theory and practice; (c) need to be applied in approximations of teaching as well as school-based teaching… (p. 2).

Secondly, six articles [9, 20, 23, 25, 27, 29] (Appendix A) indicate that core practices are essential and frequent aspects of the teaching profession. These include tasks and activities that are necessary to be a skilful teacher, be able to cope with teaching responsibilities, and be effective in teaching. This second conceptual approach, while similar to the first in terms of teaching and learning core practices, places greater emphasis on the idea of becoming a competent teacher through teacher education and further professional development. Finally, in third place, only one article [16] conceptualises core practices as ‘good teaching practices’ that are research-based: “core practices of good teaching that draw on research that associates disciplinary teaching practices with student learning.” (Peercy et al., 2022).

3.1.2. Core Practices as Key Theoretical Constructs

In this second set of conceptualisations of CPs, the studies emphasise the theoretical value of CPs for pedagogical theory and practice, including their role in ambitious teaching and their impact on improving the achievements of students.

The analysis revealed that four articles [4, 5, 11, 12] (Appendix A) highlighted, in their definitions, the theoretical implications of core practices in the context of teaching practice. It is pointed out that they form part of an ambitious approach to teaching that is closely aligned with the learning objectives of various disciplines. This approach acknowledges the complexity and intersubjectivity of educational work. Core practices would be assimilated into learning communities and allow teachers to learn from their students and improve the teaching processes they implement in the classroom, proving to be a key construct for teaching theory.

On the other hand, three articles [7, 21, 24] (Appendix A) simply define them as essential teaching practices that efficiently guide and support student learning, highlighting their theoretical value for improving academic performance, yet without explicitly establishing their relevance.

3.2. Core Practices Empirically Addressed by the Recent Literature

In relation to the second question that guided this review, which core practices have been subjected to empirical investigation? Of the 39 articles, 16 do not report findings, results or analysis of specific core practices, while the remaining 23 articles report empirical results on one or more core practices.

Regarding the core practices addressed in the 23 articles analysed, the most studied core practices were identified as Eliciting student thinking, Explaining and modelling, Building a positive learning environment, and Leading discussions with students (see Table A1 in Appendix B).

Most of these studies focused on investigating only one specific core practice with its constituent movements (e.g., 4), with the simultaneous study of five or more core practices in the same training programme being infrequent [9, 29, 30, 38, 39] (Appendix A).

Finally, the studies employed core practices (e.g., Making students’ thinking visible vs. Eliciting student thinking) and variants to specify the subject matter or discipline to which they apply (e.g., Eliciting and responding to students mathematical ideas). As can be seen in Table A1 (see Appendix B), all 23 studies were developed in the context of designing, developing or implementing training programmes for pre-service and in-service teachers, based on samples of novice teachers and pre-service teachers, and to a lesser extent on populations of in-service teachers and teacher educators.

3.3. Methodological Approaches in Core Practices Studies

In relation to the third research question, what methodological approaches are employed to study core practices? Of the 39 articles, 23 reported methodological treatments that enabled the researchers to obtain empirical results on one or more core practices. These treatments are primarily reflected in the research designs and how the CPs investigated in the study are operationalised for further analysis.

3.3.1. Design of Studies Empirically Investigating Core Practices

The 23 studies that investigated the core practices presented in Table A2 (see Appendix C) reported a variety of methodological designs, with qualitative or mixed studies with a descriptive purpose being the most prevalent (Descriptive/Exploratory studies), and to a lesser extent, quantitative studies with an associative purpose (Associational/Correlational). The data collection techniques employed were primarily videotaping of pedagogical performances [1, 5, 7, 9, 17, 18, 19, 23, 24, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 38], followed by semi-structured interviews [27, 29, 30, 31] (Appendix A), review of documents from collaborative analysis meetings or lesson plans [16, 17, 18, 19, 27, 29, 30, 31, 39], and to a lesser extent, the application of standardised measurement instruments [4, 37] (Appendix A) or assessment tasks [20, 21].

Regarding Descriptive/Exploratory studies, Table A2 (see Appendix C) shows that the research designs reported a range from multiple case studies to mixed designs and participatory research. Despite this diversity, most of these studies share exploratory–descriptive qualitative approaches. Nineteen studies stated an aim to describe the teaching, learning, reflection and/or enacted core practices, highlighting the challenges and strengths of teacher/professional education, as their research purpose. The studies categorised as Descriptive mostly focused on reporting frequencies of use, specific movements and/or performance vignettes of the core practices studied, while only six Descriptive studies explored specific core practices in the context of other theoretically related or broader educational phenomena [16, 17, 19, 20, 27, 31].

Regarding the Correlational/Associative studies, as shown in Table A2 (see Appendix C), three studies were conducted with the objective of establishing relationships or associations between specific core practices and other variables of interest [4, 23, 37] from a strictly quantitative approach. In other words, these studies present associations between a core practice and other variables, such as feedback received by coaches, critical thinking and pedagogical knowledge.

3.3.2. Operationalisation of the Investigated CPs

The core practices (CPs) investigated were operationalised for analytical treatment mainly in two ways: the use of codebooks and the use of measurement instruments. Qualitative analysis based on the codebooks of the core practices and their constituent movements was the most frequent treatment.

Regarding the use of codebooks, Table A2 (see Appendix C) shows that most of the studies operationalised the core practices studied in codebooks, in which their definitions and constitutive movements are made explicit and are presented as specific and observable actions performed by teachers. These codebooks were applied to the data collected to identify specific CPs and their movements. On the other hand, two studies [32, 34] specify that they used codebooks in a checklist format due to its feasibility to be applied to the data, thus determining the presence/absence of the constituent elements, while three other studies [9, 21, 23] indicate that they employed a rubric format in order to differentiate performance levels of teaching performance from core practice. An example of this type of study is the study conducted by (Meneses et al., 2023), who designed a codebook that characterised the specific movements of core practices to subsequently code video recordings and audio transcriptions of pre-service teacher lessons.

As regards the use of measurement instruments, the results suggest that two of the three Correlational studies [4, 37] used standardised procedures for an accurate measurement of core practices, including the use of a standardised observation instrument and a standardised performance assessment. For example, the study by Davis and Palincsar (2023), examined the relationship between the feedback-giving ability of educator teachers (coaches) and the subsequent thinking elicitation (CP) ability of pre-service teachers when confronted with their professional practice. For this purpose, the authors used the CLASS instructional support dimension as a standardised measure of teachers’ performance (proficiency) in this core practice, establishing statistical relationships between feedback received and level of teacher performance in eliciting thinking.

Finally, six studies did not report how the CPs investigated were operationalised.

4. Discussion

The aim of this review was to obtain insights on the study of core practices in the recent scientific literature to guide the identification and incorporation of these practices in teacher training, ensuring that they represent a challenge. We then analysed the results in relation to early childhood education, as this places the debate in a relevant field of training (Kumar, 2020; López-Jiménez et al., 2021).

The findings show that the conceptualisation of core practices in recent studies follows the five original dimensions proposed by (Grossman et al., 2009a, 2009b): teachability in teacher education programmes, proficiency, ambitious teaching, improvement of student achievement, and research-based support. However, most recent studies place greater emphasis on the teachability dimension of core practices, particularly in teacher education programmes for pre-service teachers. This emphasis on the teachability of these practices is consistent with the literature that addresses initial teacher education, but it is also limiting, as it often neglects research in classroom contexts with experienced teachers (in-service teachers) or in more complex educational settings, such as urban, rural, or inclusive schools (Tricco et al., 2018).

The studies reviewed (e.g., Peercy et al., 2020) call for a responsive study of core practices in classrooms where high levels of vulnerability and barriers to teacher performance are prevalent, a situation that is not desirable when studies are developed exclusively in the context of pre-service teacher training where teaching is cautious and simplified in complexity. Consequently, a predominantly unidimensional conceptualisation of core practices biases their identification in fields of recent application, such that an analysis was not conducted to determine whether a highly teachable practice effectively improves student learning (Kavanagh & Danielson, 2020) and whether it is a viable practice to be enacted by in-service teachers in specific performance contexts after a couple of years of professional practice (Kavanagh et al., 2020; Shaughnessy et al., 2021b).

On the other hand, the incorporation of the core practices in early childhood education training would allow teachers to have a common language, which would facilitate the proactive and spontaneous deepening of children’s thinking and understanding according to their own interests and motivations during pedagogical interactions in the classroom (Hedges & Cooper, 2018; López-Jiménez, 2023). Likewise, the stages of development in which the children find themselves could also be considered in the analysis of these practices (Bogatić & Jevtić, 2025).

Considering the aforementioned considerations, it is imperative that early childhood teacher education programmes that aspire to incorporate elements of practice-based training (i.e., core practices) examine the typical practices performed by experienced in-service teachers considering the diversity of educational settings and their communities’ assessment of these practices (Peercy et al., 2020). The adoption of lists of core practices from other educational levels or disciplines may prove to be decontextualised and inappropriate for the early childhood education level. Similarly, core practices that are commonly studied at higher levels of education (e.g., Eliciting student thinking and Explaining and modelling) must be adapted for early childhood learners who are still developing their language and thinking. Furthermore, it is of paramount importance to understand which core practices are efficacious with young children and what impact they have on their learning and development. Thus, a particular challenge at this educational level is to identify core practices relevant to the teaching and learning process, taking into account the pedagogical principles of this educational level, such as play, inclusion and cultural relevance, as well as the teacher’s role in facilitating learning through a mediating and responsive attitude.

Core practices propose that educational practices should be intentional and adapted to the needs of students at different stages of development (Harti et al., 2024). In early childhood education, it is essential to differentiate strategies for infants and preschoolers, as each group has unique learning and developmental needs that require specific pedagogical approaches. For example, play and exploration are fundamental in the education of the youngest children, while more structured strategies may be more appropriate for older children (4 to 6 years).

On the other hand, given the necessity for field studies, the findings of this review show that core practices can be empirically studied through a range of methodological approaches, without being confined to quantitative, mixed, or qualitative designs (Shaughnessy et al., 2021a). Indeed, core practices, as a study phenomenon, can be approached through qualitative (e.g., coding of video recordings with codebooks) and quantitative (e.g., correlation analysis with measurement instruments) analyses.

The core practice approach emphasises the need to integrate theory with practice (Matsumoto-Royo & Conget, 2024). This means that, when discussing the core practices, it is crucial not only to describe them, but also to connect how they are implemented in the classroom and how they are supported by theoretical research. By doing so, it can be demonstrated to early childhood educators and teacher trainers why these practices are relevant and necessary in their daily work (Harti et al., 2024).

These practices, conceived as essential and recurring actions in teaching, facilitate the transfer of pedagogical skills to different educational settings. Furthermore, by focusing on fundamental aspects of teaching—such as classroom management, interaction with children and formative assessment—the core practices provide educators with concrete tools to improve their performance from the initial stage of their training, thus guaranteeing more effective teaching that is aligned with the needs of child development.

In addition, the findings reveal a series of methodological decisions that depend on the design and research questions, such as the number of core practices to be studied, the specific movements comprising each core practice studied, and the size grain of the core practices and their movements (Cuenca, 2021). When these decisions are applied to the identification of core practices in fields of recent application, questions arise as to which option is more pertinent. Regarding the first decision, it may be impractical to include a list of more than six core practices in a single study given that each of these comprises specific pedagogical movements. Regarding the second decision, it appears that determining a priori the movements that comprise a core practice exclusively from a literature review or expert consultation does not seem to be a context-sensitive option (Hedges & Cooper, 2018). Therefore, as core practices are highly dependent on specific teaching spaces, this makes the refinement and inductive piloting of instruments and codebooks a more pertinent undertaking (Matsumoto-Royo & Conget, 2024). Finally, regarding the third type of decisions, refining the size grain of core practices and their movements in studies aimed at their identification is a permanent challenge (Cross et al., 2024; Harti et al., 2024) that should be guided by their relevance for teacher training, taking into account the skills and movements that teachers in training need to learn (Cash et al., 2022; Millican & Forrester, 2018).

The latter is clearly illustrated in the field of early childhood teacher training because the identification of core practices and very generic movements (e.g., teaching using play as a means of learning) does not allow for their fruitful incorporation into training programmes since pre-service teachers will have difficulties in decomposing the practice and subsequently enacting it in specific teaching situations. This would not be very different from training based on general principles or teaching knowledge that establish that education at this educational level should be inclusive, developmentally appropriate and playful (Cross et al., 2024). Similarly, identifying very specific core practices and movements (e.g., talking to young children while they play and eat) restricts teacher training to a very technical and mechanical levels (Peercy et al., 2020), without guiding teaching towards more ambitious and challenging pedagogical levels (Grossman et al., 2009b; Matsumoto-Royo & Conget, 2024). Both situations are especially harmful at an educational level where the development of young children is highly permeable to what their teachers do, and abundant prior research on teaching practice is necessary for an appropriate identification and selection of core practices to be incorporated into teacher-training programmes. Prior research on teaching methodologies is essential for the appropriate identification and selection of core practices to be incorporated into teacher-training programmes.

To conclude this discussion, the findings prompt us to consider whether a single approach exists for identifying, selecting, and integrating core practices in recently implemented training programmes. Rather, it may be more beneficial to allow for the coexistence of empirical field approaches as well as consultation with experts, collaborative analysis with in-service teachers, and a review of the existing literature (Kavanagh et al., 2020; Owens et al., 2021). This is because core practices are highly complex (Grossman et al., 2009b) and multidimensional constructs (Grossman et al., 2009a) that require multiple approaches to fully elucidate all their dimensions. On the one hand, the findings of this review show that all empirical studies started with a manageable set of core practices that were supported by substantial evidence from previous studies and valued by the expert community. On the other hand, the fact that the ultimate purpose of identifying these practices is to ascertain their potential relevance in teacher-training programmes does not imply that their empirical identification is limited primarily to case studies of pre-service teacher-training programmes, an issue that (Grossman & McDonald, 2008) pointed out more than a decade ago. Finally, as core practices are highly complex constructs with several dimensions, it is the responsibility of teacher-training programmes to weigh all these dimensions before including them in their curricula considering the multiple forms of evidence (Grossman et al., 2009b).

Despite the importance of this review for understanding the empirical study of fundamental practices in teacher education, it is necessary to consider some limitations. First, most of the studies analysed focus on initial teacher education programmes, which makes it difficult to understand how these practices are developed and consolidated in real classroom settings with practicing teachers. In addition, the predominance of qualitative and descriptive approaches in the research reviewed limits the identification of causal relationships between these practices and their impact on student learning, underscoring the need for studies that employ correlational or experimental methodologies. On the other hand, although core practices have been widely adopted in teacher education, their identification still relies heavily on expert consultation, which could provide a partial view of their applicability in different educational contexts.

5. Conclusions

The purpose of this review was to characterise the study of core practices, identifying their conceptualisations and methodological approaches in studies published between 2019 and 2023. Three key contributions emerge from this analysis to advance in the identification of core practices and their subsequent incorporation into teacher-training programmes.

First, given that the conceptualisation of core practices is dominated by the teachability dimension in teacher education programmes, this emphasis should not undermine the empirical dimension that also defines what a core practice is.

The identification of core practices specific to certain pedagogical disciplines should consider that they are recurrent empirical phenomena in successful teachers and that they have a demonstrable impact on the improvement of teaching and student learning. When a set of core practices is incorporated into teacher-training programmes, it is essential to ensure that these practices are effectively present in experienced teachers in that region or context, and that their teaching is valued as challenging and of high quality.

Second, regarding the empirical dimension of core practices, the recent literature presents a variety of methodological approaches that ensure an empirical treatment of these practices in populations of in-service and pre-service teachers. These approaches range from qualitative studies with a descriptive approach to longitudinal and correlational studies using measurement instruments and coding procedures primarily applied on observed or recorded teaching practices. This demonstrates that empirical identification of core practices in the field is a feasible task from which teacher education programmes can benefit. For example, research can determine the specific movements that constitute certain core practices in diverse and situated contexts, their frequency of use, and their empirical relationship to other educational phenomena, such as feedback and pedagogical knowledge.

Finally, the empirical identification of core practices for incorporation into training programmes serves to complement methodologies based on expert consultation and literature review. Both approaches enrich each other, providing a more robust and comprehensive basis for the identification and selection of core practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, T.L.-J., V.Z., V.T. and N.V.; Methodology, T.L.-J., V.Z., V.T., C.H., N.V. and A.A.; Formal Analysis, T.L.-J., V.Z., V.T., C.H., N.V. and A.A.; Investigation, N.V.; Writing—Original Draft, T.L.-J., V.Z., V.T. and N.V.; Writing—Review and Editing, V.Z., V.T. and A.A.; Supervision, T.L.-J.; Project Administration, T.L.-J. Funding Acquisition, T.L.-J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (ANID) through FONDECYT Project Initiation No. 11231120.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study. Data sharing does not apply to this article. Data are contained within this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A presents the list of articles reviewed and analysed.

| Article Number | Citation | Author | Year | Title | Journal |

| 1 | (Alston & Danielson, 2021) | Alston, C.; Danielson, K. A. | 2021 | Enacting thinking: supporting teacher candidates in modeling writing strategies | Literacy Research and Instruction |

| 2 | (Bennett & Jamil, 2022) | Bennett, A.; Jamil, F. | 2022 | Kindergarten teacher responses to a contextualized professional development workshop on STEAM teaching | International Journal of Teacher Education and Professional Development |

| 3 | (Buchbinder & McCrone, 2020) | Buchbinder, O.; McCrone, S. | 2020 | Preservice teachers learning to teach proof through classroom implementation: successes and challenges | The Journal of Mathematical Behavior |

| 4 | (Cash et al., 2022) | Cash, |A.H.; Dack, H.; Leach, W. | 2022 | Examining coaches’ feedback to preservice teacher candidates on a core practice | International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education |

| 5 | (Chan, 2023) | Chan K. K. H. | 2023 | Eliciting and working with student thinking: preservice science teachers’ enactment of core practices when orchestrating collaborative group work | Journal of Research in Science Teaching |

| 6 | (Christiansen & Erixon, 2021) | Christiansen I. M.; Erixon E. L. | 2021 | Opportunities to learn mathematics pedagogy and learning to teach mathematics in Swedish mathematics teacher education: a survey of student experiences | European Journal of Teacher Education |

| 7 | (Colonnese et al., 2022) | Colonnese, M.W.; Reinke, L.T.; Polly, D. | 2022 | An analysis of the questions elementary education teacher candidates pose to elicit mathematical thinking | Action in Teacher Education |

| 8 | (Conroy et al., 2022) | Conroy, M. A.; Sutherland, K. S.; Granger, K. L.; Marcoulides, K. M.; Feil, E.; Wright, J.; Ramos, M.; Montesion, A. | 2022 | Effects of BEST in CLASS-Web on teacher outcomes: a preliminary investigation | Journal of Early Intervention |

| 9 | (Davis & Palincsar, 2023) | Davis, E. A; Palincsar, A. S. | 2023 | Engagement in high-leverage science teaching practices among novice elementary teachers | Science Education |

| 10 | (Fink et al., 2019) | Fink Chorzempa, B.; Smith, M. D.; Sileo, J. M. | 2019 | Practice-based evidence: a model for helping educators make evidence-based decisions | Teacher Education and Special Education |

| 11 | (Grossman & Dean, 2019) | Grossman, P.; Dean, C. G. P. | 2019 | Negotiating a common language and shared understanding about core practices: The case of discussion | Teaching and teacher education |

| 12 | (Hawkins et al., 2022) | Hawkins, L. K.; Martin, N. M.; Bottomley, D.; Shanahan, B.; Cooper, J. | 2022 | Toward deeper understanding of children’s writing: pre-service teachers’ attention to local and global Text features at the start and end of writing-focused coursework | Literacy Research and Instruction |

| 13 | (Hogan et al., 2022) | Hogan, E.; Gannon, C.; Anthony, M.; Byrne, V.; Dhingra, N. | 2022 | Transfer, adaptation, and loss in practice-based teacher education amidst COVID-19 | The New Educator |

| 14 | (Holstein et al., 2022) | Holstein, A.; Weber, K. E.; Prilop, C. N.; Kleinknecht, M. | 2022 | Analyzing pre- and in-service teachers? feedback practice with microteaching videos | Teaching and Teacher Education |

| 15 | (Howell & Mikeska, 2021) | Howell, H.; Mikeska, J. N. | 2021 | Approximations of practice as a framework for understanding authenticity in simulations of teaching | Journal of Research on Technology in Education |

| 16 | (Johnson & Mawyer, 2019) | Johnson, H. J.; Mawyer, K. K. N. | 2019 | Teacher candidate tool-supported video analysis of students’ science thinking | Journal of Science Teacher Education |

| 17 | (Kane, 2020) | Kane, B. D. | 2020 | Equitable teaching and the core practice movement: preservice teachers’ professional reasoning | Teachers College Record |

| 18 | (Kavanagh & Danielson, 2020) | Kavanagh, S. S.; Danielson, K. A. | 2020 | Practicing justice, justifying practice: toward critical practice teacher education | American Educational Research Journal |

| 19 | (Kavanagh et al., 2020) | Kavanagh, S. S.; Metz, M.; Hauser, M.; Fogo, B.; Taylor, M. W.; Carlson, J. | 2020 | Practicing responsiveness: using approximations of teaching to develop teachers’ responsiveness to students’ ideas | Journal of Teacher Education |

| 20 | (Lee & Lee, 2023) | Lee, J. E.; Lee, M. Y. | 2023 | How elementary prospective teachers use three fraction models: their perceptions and difficulties | Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education |

| 21 | (Marzabal et al., 2019) | Marzabal, A.; Merino C.; Moreira, P.; Delgado, V. | 2019 | Assessing science teaching explanations in Initial teacher education: how is this teaching practice transferred across different chemistry topics? | Research in science education |

| 22 | (Matsumoto-Royo et al., 2022) | Matsumoto-Royo, K.; Ramírez-Montoya, M. S.; Glasserman-Morales, L. D. | 2022 | Lifelong Learning and Metacognition in the Assessment of Pre-service Teachers in Practice-Based Teacher Education | Frontiers in Education |

| 23 | (Meneses et al., 2023) | Meneses, A.; Nussbaum, M.; Veas M. G.; Arriagada, S. | 2023 | Practice-based 21st-century teacher education: design principles for adaptive expertise | Teaching and Teacher Education |

| 24 | (Mikeska & Howell, 2020) | Mikeska, J. N; Howell, H. | 2020 | Simulations as practice-based spaces to support elementary teachers in learning how to facilitate argumentation-focused science discussions | Journal of Research in Science Teaching |

| 25 | (Mikeska et al., 2023) | Mikeska, J. N.; Howell, H.; Kinsey, D. | 2023 | Inside the black box: how elementary teacher educators support preservice teachers in preparing for and learning from online simulated teaching experiences | Teaching and Teacher Education |

| 26 | (Mikeska & Lottero-Perdue, 2022) | Mikeska, J. N.; Lottero-Perdue, P. S. | 2022 | How preservice and in-service elementary teachers engage student avatars in scientific argumentation within a simulated classroom environment | Science Education |

| 27 | (Nel & Marais, 2021) | Nel, P. C.; Marais, D. E. | 2021 | Addressing the wicked problem of feedback during the teaching practicum | Perspectives in Education |

| 28 | (Neumann et al., 2021) | Neumann, K. L.; Alvarado-Albertorio, F.; Ramírez-Salgado, A. | 2021 | Aligning with practice: examining the effects of a practice-based educational technology course on preservice teachers’ potential to teach with technology | TechTrends |

| 29 | (Peercy et al., 2020) | Peercy, M. M.; Kidwell, T.; Lawyer, M. D.; Tigert, J.; Fredricks, D.; Feagin, K.; Stump, M. | 2020 | Experts at being novices: what new teachers can add to practice-based teacher education efforts | Action in Teacher Education |

| 30 | (Peercy et al., 2022) | Peercy, M. M.; Tigert, J.; Fredricks, D.; Kidwell, T.; Feagin, K.; Hall, W.; Himmel, J.; DeStefano Lawyer, M. | 2022 | From humanizing principles to humanizing practices: exploring core practices as a bridge to enacting humanizing pedagogy with multilingual students | Teaching and Teacher Education |

| 31 | (Schutz et al., 2019) | Schutz, K. M.; Danielson, K. A.; Cohen, J. | 2019 | Approximations in english language arts: scaffolding a shared teaching practice | Teaching and Teacher Education |

| 32 | (Shaughnessy et al., 2019) | Shaughnessy, M.; Boerst, T. A.; Farmer, S. O. | 2019 | Complementary assessments of prospective teachers’ skill with eliciting student thinking | Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education |

| 33 | (Shaughnessy et al., 2021a) | Shaughnessy, M.; DeFino, R.; Pfaff, E.; Blunk, M. | 2021 | I think I made a mistake: how do prospective teachers elicit the thinking of a student who has made a mistake? | Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education |

| 34 | (Shaughnessy et al., 2021b) | Shaughnessy M.; Garcia N. M.; O’Neill, M. K.; Selling, S. K.; Willis, A. T.; Wilkes C. E., II; Salazar, S.B.; Ball D. L. | 2021 | Formatively assessing prospective teachers’ skills in leading mathematics discussions | Educational Studies in Mathematics |

| 35 | (Thompson & Emmer, 2019) | Thompson, S. L.; Emmer, E. | 2019 | Closing the experience gap: the influence of an immersed methods course in science | Journal of Science Teacher Education |

| 36 | (Trevisan et al., 2020) | Trevisan, A. L.; Ribeiro, A. J.; da Ponte, J. P. | 2020 | Professional learning opportunities regarding the concept of function in a practice-based teacher education program | International Electronic Journal of Mathematics Education |

| 37 | (Vogelsang et al., 2022) | Vogelsang, C.; Kulgemeyer, C.; Riese, J. | 2022 | Learning to plan by learning to reflect?—exploring relations between professional knowledge, reflection skills, and planning skills of preservice physics teachers in a one-semester field experience | Education Sciences |

| 38 | (Wæge & Fauskanger, 2021) | Waege, K.; Fauskanger, J. | 2021 | Teacher time outs in rehearsals: in-service teachers learning ambitious mathematics teaching practices | Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education |

| 39 | (Xie et al., 2020) | Xie, X.; Ward, P.; Oh, D.; Li, Y.; Atkinson, O.; Cho, K.; Kim, M. | 2020 | Preservice physical education teacher’s development of adaptive competence | Journal of Teaching in Physical Education |

| Nota: Appendix A presents the list of articles reviewed and analysed. | |||||

Appendix B

Appendix B presents Table A1.

Table A1.

Core practices empirically studied in the reviewed articles.

Table A1.

Core practices empirically studied in the reviewed articles.

| Article Number | Core Practices | Population |

|---|---|---|

| 38 | Launching problems | In-service elementary teachers |

| 38 | Using mathematical representations | In-service elementary teachers |

| 38 | Aiming towards a mathematical goal | In-service elementary teachers |

| 38 | Facilitating student talk | In-service elementary teachers |

| 38 | Organising the board | In-service elementary teachers |

| 38 | Eliciting and responding to students’ mathematical ideas | In-service elementary teachers |

| 4, 5, 7, 16, 32, 33 | Eliciting student thinking | Pre-service science teachers; pre-service teachers; pre-service elementary teachers |

| 16 | Supporting ongoing changes in student thinking | Pre-service science teachers |

| Eliciting and probing students’ thinking about science | Pre-service elementary teachers and novice teachers | |

| 9, 24 | Supporting students to construct and discuss scientific explanations and arguments | Pre-service elementary teachers and novice teachers |

| 9 | Choosing and using representations examples and models of science content and practice | Pre-service elementary teachers and novice teachers |

| 21 | Explaining science ideas | Chemistry pre-service secondary teachers |

| 9 | Leading science sensemaking discussions | Pre-service elementary teachers and novice teachers |

| 9 | Setting up and managing small-group investigations | Pre-service elementary teachers and novice teachers |

| 9 | Establishing norms of discourse and work that reflect the discipline of science | Pre-service elementary teachers and novice teachers |

| 1, 20, 23, 27 | Explaining and modelling | Pre-service elementary teachers; ELA pre-service secondary teachers |

| 23 | Implementing organisational routines | Pre-service elementary teachers |

| 23 | Providing feedback to students | Pre-service elementary teachers |

| 17 | Making students’ thinking visible | ELA pre-service teachers |

| 31 | Facilitating discussion and modelling | ELA teacher educators |

| 18 | Facilitating text-based discussions | Teacher educators; pre-service elementary teachers |

| 19, 23, 34 | Lead discussions with students | Novice elementary teachers; pre-service elementary teachers; novice secondary teachers |

| 29, 30, 39 | Build a positive learning environment | Pre-service physical education teachers; ESOL novice teachers; ESOL pre-service teachers |

| 29, 30 | Knowing the students | ESOL novice teachers; ESOL pre-service teachers |

| 29, 30 | Developing positive relationships with colleagues, families, stakeholders, and self | ESOL novice teachers; ESOL pre-service teachers |

| 29, 30 | Planning and enacting content and language instructions in ways that meet students at their current level | ESOL novice teachers; ESOL pre-service teachers |

| 29, 30 | Supporting language and literacy development | ESOL novice teachers; ESOL pre-service teachers |

| 29, 30 | Assessing in ways that are attentive to students’ language proficiency | ESOL novice teachers; ESOL pre-service teachers |

| 37 | Reflection | Pre-service physics teachers |

| 37 | Lesson Planning | |

| 39 | Establishing rules and routines in the teaching environment | Pre-service physical education teachers |

| 39 | Checking students understanding during and at the conclusion of lesson | Pre-service physical education teachers |

| 39 | Providing clear and precise instructions | Pre-service physical education teachers |

| 39 | Coordinating and adjusting instruction based on students’ needs during a lesson | Pre-service physical education teachers |

| 39 | Breaking down content into smaller elements as task statements | Pre-service physical education teachers |

Note. ELA: English language arts; ESOL: English for speakers of other languages; Novice teachers: teachers with 0 to 4 years of teaching experience.

Appendix C

Appendix C presents Table A2.

Table A2.

Methodological approach to empirically studied core practices.

Table A2.

Methodological approach to empirically studied core practices.

| Article Number | Research Design of Study | Purpose of the Study | Pedagogical [Enacted] Performance Context | Operationalisation of the Core Practice |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Multi-case study * | Descriptive | Simulated practice | Codebook applied to video recordings |

| 4 | Cross-sectional quantitative design | Correlational | Professional practice | Classroom assessment scoring system (CLASS), domain of instructional support |

| 5 | Exploratory qualitative study | Descriptive | Simulated practice | Codebook applied to video recordings and transcriptions |

| 7 | Multi-case study * | Descriptive | Professional practice | Codebook applied to transcriptions of video or audio recordings |

| 9 | Longitudinal study | Descriptive | Professional practice and first year of teaching | Coding rubrics applied to video recordings |

| 16 | Qualitative study | Descriptive | Professional practice | Non-coded core practice |

| 17 | Qualitative multiple case study | Descriptive | Simulated practice | Non-coded core practice |

| 18 | Qualitative case study of one course | Descriptive | Professional practice | Codebook applied to video recordings, lessons plans and other documents |

| 19 | Qualitative case study | Descriptive | Simulated practice | Non-coded core practice |

| 20 | Observational study | Descriptive | Simulated practice | Non-coded core practice |

| 21 | Exploratory case study | Descriptive | Simulated practice | Coding rubrics applied to written assignments |

| 23 | Design-based research | Correlational | Professional practice | Codebook and performance score range applied to video recordings |

| 24 | Case study * | Descriptive | Virtual simulated practice | Codebook applied to video recordings |

| 27 | Exploratory case study | Descriptive | Simulated practice | Non-coded core practice |

| 29 | Participatory design research | Descriptive | Professional practice and first years of teaching | Codebook applied to lesson observations and debriefing interviews |

| 30 | Participatory design research | Descriptive | Firsts year of teaching | Codebook applied to lesson observations, video recordings and transcriptions of interviews and meetings |

| 31 | Multi-case study | Descriptive | Methods courses | Non-coded core practices |

| 32 | Multi-case study * | Descriptive | Professional practice and simulated practice | Observational checklist applied to video recordings |

| 33 | Not declared | Descriptive | Simulated practice | Codebook applied to video recordings |

| 34 | Multi-case study * | Descriptive | First years of teaching | Observational checklist applied to video recordings |

| 37 | Pre-post field study | Correlational | Professional practice | Standardised performance assessment (digital format) |

| 38 | Qualitative case study * | Descriptive | Rehearsals in professional development | Codebook applied to video recordings |

| 39 | Mixed-Method cases studies | Descriptive | Lab small-group peer teaching setting and school-based setting with groups of 5–8 pupils | Codebook applied to lesson plans |

Note. * Type of study not specified in the article. The type of study was categorised based on the proposal of Johnson and Mawyer (2019). CLASS: The Classroom Assessment Scoring System.

References

- Alston, C., & Danielson, K. A. (2021). Enacting thinking: Supporting teacher candidates in modeling writing strategies. Literacy Research and Instruction, 60(5), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assarroudi, A., Heshmati Nabavi, F., Armat, M. R., Ebadi, A., & Vaismoradi, M. (2018). Directed qualitative content analysis: The description and elaboration of its underpinning methods and data analysis process. Journal of Research in Nursing, 23, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barahona, M., & Davin, K. J. (2021). A practice-based approach to foreign language teacher preparation: A cross-continental collaboration. PROFILE: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 23, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A., & Jamil, F. (2022). Kindergarten teacher responses to a contextualized professional development workshop on STEAM teaching. International Journal of Teacher Education and Professional Development, 5(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogatić, K., & Jevtić, A. (2025). Rethinking play and child-centredness within early childhood curriculum in Croatia. Journal of Childhood, Education & Society, 6(1), 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchbinder, O., & McCrone, S. (2020). Preservice teachers learning to teach proof through classroom implementation: Successes and challenges. The Journal of Mathematical Behavior, 58(2), 100779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, A. H., Dack, H., & Leach, W. (2022). Examining coaches’ feedback to preservice teacher candidates on a core practice. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 11(3), 308–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K. K. H. (2023). Eliciting and working with student thinking: Preservice science teachers’ enactment of core practices when orchestrating collaborative group work. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 60(5), 1014–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, I. M., & Erixon, E. L. (2021). Opportunities to learn mathematics pedagogy and learning to teach mathematics in Swedish mathematics teacher education: A survey of student experiences. European Journal of Teacher Education, 47(1), 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarà, M. (2019). El problema teoría-práctica en los modelos de formación del profesorado: Una mirada psicológica. Estudios Pedagógicos (Valdivia), 45(2), 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonnese, M. W., Reinke, L. T., & Polly, D. (2022). An analysis of the questions elementary education teacher candidates pose to elicit mathematical thinking. Action in Teacher Education, 44(3), 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, M. A., Suther-land, K. S., Granger, K. L., Marcoulides, K. M., Feil, E., Wright, J., Ramos, M., & Montesion, A. (2022). Effects of BEST in CLASS-Web on teacher outcomes: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Early Intervention, 44(2), 130–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, E., Dobson, M., & Brooks, J. S. (2024). Leadership competencies in early childhood education: Design and validation of a survey tool. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 49(4), 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca, A. (2021). Proposing core practices for social studies teacher education: A qualitative content analysis of inquiry-based lessons. Journal of Teacher Education, 72(3), 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher education around the world: What can we learn from international practice? European Journal of Teacher Education, 40(3), 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, E. A., & Palincsar, A. S. (2023). Engagement in high-leverage science teaching practices among novice elementary teachers. Science Education, 107(2), 291–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, C. B., Smith, M. D., & Sileo, J. M. (2019). Practice-based evidence: A model for helping educators make evidence-based decisions. Teacher Education and Special Education, 42(1), 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogo, B. (2014). Core practices for teaching history: The results of a Delphi panel survey. Theory & Research in Social Education, 42(2), 151–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forzani, F. M. (2014). Understanding “core practices” and “practice-based” teacher education: Learning from the past. Journal of Teacher Education, 65(4), 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosser-Clarkson, D., & Neel, M. A. (2020). Contrast, commonality, and a call for clarity: A review of the use of core practices in teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 71(4), 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P., Compton, C., Igra, D., Ronfeldt, M., Shahan, E., & Williamson, P. (2009a). Teaching practice: A cross-professional perspective. Teachers College Record, 111(9), 2055–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P., & Dean, C. G. P. (2019). Negotiating a common language and shared understanding about core practices: The case of discussion. Teaching and Teacher Education, 80(2), 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P., Hammerness, K., & McDonald, M. (2009b). Redefining teaching, re-imagining teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 15(2), 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P., & McDonald, M. (2008). Back to the future: Directions for research in teaching and teacher education. American Educational Research Journal, 45(1), 184–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guirao, S. J. A. (2015). Utilidad y tipos de revisión de literatura. Ene, 9(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harti, F., Chausseboeuf, L., Santelices, M. P., & Wendland, J. (2024). Modalities and effectiveness of interventions aimed at promoting teacher–child interaction to reduce children’s externalizing behavior problems in childcare centers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Early Childhood Education Journal, 52, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, L. K., Martin, N. M., Bottomley, D., Shanahan, B., & Cooper, J. (2022). Toward deeper understanding of children’s writing: Pre-service teachers’ attention to local and global Text features at the start and end of writing-focused coursework. Literacy Research and Instruction, 61(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, H., & Cooper, M. (2018). Relational play-based pedagogy: Theorising a core practice in early childhood education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(4), 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, E., Gannon, C., Anthony, M., Byrne, V., & Dhingra, N. (2022). Transfer, adaptation, and loss in practice-based teacher education amidst COVID-19. The New Educator, 18(5), 256–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holstein, A., Weber, K. E., Prilop, C. N., & Kleinknecht, M. (2022). Analyzing pre- and in-service teachers? feedback practice with microteaching videos. Teaching and Teacher Education, 117(3), 103817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, H., & Mikeska, J. N. (2021). Approximations of practice as a framework for understanding authenticity in simulations of teaching. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 53(1), 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huanca-Arohuanca, J. W. (2022). Combate cuerpo a cuerpo para entrar a la Liga de los Dioses: Scopus y Web of Science como fin supremo. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia, 27, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, H. J., & Mawyer, K. K. (2019). Teacher candidate tool-supported video analysis of students’ science thinking. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 30(5), 528–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, B. D. (2020). Equitable teaching and the core practice movement: Preservice teachers’ professional reasoning. Teachers College Record, 122(11), 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, S. S., & Danielson, K. A. (2020). Practicing justice, justifying practice: Toward critical practice teacher education. American Educational Research Journal, 57(1), 69–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, S. S., Metz, M., Hauser, M., Fogo, B., Taylor, M. W., & Carlson, J. (2020). Practicing responsiveness: Using approximations of teaching to develop teachers’ responsiveness to students’ ideas. Journal of Teacher Education, 71(1), 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloser, M. (2014). Identifying a core set of science teaching practices: A Delphi expert panel approach. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 51(9), 1185–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. (2020). Facilitating engagement with practice: Using a practice-based course model for pre-service early childhood teachers. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 44(3), 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. E., & Lee, M. Y. (2023). How elementary prospective teachers use three fraction models: Their perceptions and difficulties. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 26(5), 455–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Jiménez, T. (2023). Core practices in early childhood education: Towards a theoretical and methodological proposal. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 25, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Jiménez, T., Saballa-Pavéz, D., & Peña-Sandoval, C. (2021). Core practices that promote learning in early childhood education: A multiple case study. Psychology and Education, 58(5), 6147–6158. [Google Scholar]

- Marzabal, A., Merino, C., Moreira, P., & Delgado, V. (2019). Assessing science teaching explanations in Initial teacher education: How is this teaching practice transferred across different chemistry topics? Research in science education, 49(6), 1107–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto-Royo, K., & Conget, P. (2024). Oportunidades de aprendizaje de la práctica pedagógica en el campus universitario: Planificación, ejecución y contribución en la formación profesional de futuros docentes. Pensamiento Educativo, 61(2), 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto-Royo, K., Ramírez-Montoya, M. S., & Glasserman-Morales, L. D. (2022). Lifelong learning and metacognition in the assessment of pre-service teachers in practice-based teacher education. Frontiers in Education, 7, 879238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, M., Kazemi, E., & Kavanagh, S. S. (2013). Core practices and pedagogies of teacher education: A call for a common language and collective activity. Journal of Teacher Education, 64(5), 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses, A., Nussbaum, M., Veas, M. G., & Arriagada, S. (2023). Practice-based 21st-century teacher education: Design principles for adaptive expertise. Teaching and Teacher Education, 128, 104118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikeska, J. N., & Howell, H. (2020). Simulations as practice-based spaces to support elementary science teachers in learning how to facilitate argumentation-focused discussions. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 57(9), 1356–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikeska, J. N., Howell, H., & Kinsey, D. (2023). Inside the black box: How elementary teacher educators support preservice teachers in preparing for and learning from online simulated teaching experiences. Teaching and Teacher Education, 122, 103979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikeska, J. N., & Lottero-Perdue, P. S. (2022). How preservice and in-service elementary teachers engage student avatars in scientific argumentation within a simulated classroom environment. Science Education, 106(6), 1453–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millican, J. S., & Forrester, S. H. (2018). Core practices in music teaching: A Delphi expert panel survey. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 27(3), 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, C., & Marais, E. (2021). Addressing the wicked problem of feedback during the teaching practicum. Perspectives in Education, 39(1), 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, K. L., Alvarado-Albertorio, F., & Ramírez-Salgado, A. (2021). Aligning with Practice: Examining the Effects of a Practice-Based Educational Technology Course on Preservice Teachers’ Potential to Teach with Technology. TechTrends, 65, 1027–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M., & Gough, D. (2020). Systematic reviews in educational research: Methodology, perspectives and application. In O. Zawacki-Richter, M. Kerres, S. Bedenlier, M. Bond, & K. Buntins (Eds.), Systematic reviews in educational research (pp. 3–22). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- O’Flaherty, J., Lenihan, R., Young, A. M., & McCormack, O. (2024). Developing micro-teaching with a focus on core practices: The use of approximations of practice. Education Sciences, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, D. C., Sadler, T. D., & Friedrichsen, P. (2021). Teaching practices for enactment of socio-scientific issues instruction: An instrumental case study of an experienced biology teacher. Research in Science Education, 51, 375–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peercy, M. M., Kidwell, T., Lawyer, M. D., Tigert, J., Fredricks, D., Feagin, K., & Stump, M. (2020). Experts at being novices: What new teachers can add to practice-based teacher education efforts. Action in Teacher Education, 42(3), 212–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peercy, M. M., Tigert, J., Fredricks, D., Kidwell, T., Feagin, K., Hall, W., DeStefano, M., & Lawyer, M. D. (2022). From humanizing principles to humanizing practices: Exploring core practices as a bridge to enacting humanizing pedagogy with multilingual students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 113, 103653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roller, M. R., & Lavrakas, P. J. (2015). Applied qualitative research design: A total framework approach. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schutz, K. M., Danielson, K. A., & Cohen, J. (2019). Approximations in English language arts: Scaffolding a shared teaching practice. Teaching and Teacher Education, 81, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaughnessy, M., Boerst, T. A., & Farmer, S. O. (2019). Complementary assessments of prospective teachers’ skill with eliciting student thinking. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 22(6), 607–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaughnessy, M., DeFino, R., Pfaff, E., & Blunk, M. (2021a). I think I made a mistake: How do prospective teachers elicit the thinking of a student who has made a mistake? Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 24, 335–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaughnessy, M., Garcia, N. M., O’Neill, M. K., Selling, S. K., Willis, A. T., Wilkes, C. E., II, Salazar, S., & Ball, D. L. (2021b). Formatively assessing prospective teachers’ skills in leading mathematics discussions. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 108(3), 451–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S. L., & Emmer, E. (2019). Closing the experience gap: The influence of an immersed methods course in science. Action in Teacher Education, 41(3), 300–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, A. L., Ribeiro, A. J., & da Ponte, J. P. (2020). Professional learning opportunities regarding the concept of function in a practice-based teacher education program. International Electronic Journal of Mathematics Education, 15(2), em0563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogelsang, C., Kulgemeyer, C., & Riese, J. (2022). Learning to plan by learning to reflect?—Exploring relations between professional knowledge, reflection skills, and planning skills of preservice physics teachers in a one-semester field experience. Education Sciences, 12(7), 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wæge, K., & Fauskanger, J. (2021). Teacher time outs in rehearsals: In-service teachers learning ambitious mathematics teaching practices. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 24(6), 563–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windschitl, M., Thompson, J., Braaten, M., & Stroupe, D. (2012). Proposing a core set of instructional practices and tools for teachers of science. Science Education, 96(5), 878–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X., Ward, P., Oh, D., Li, Y., Atkinson, O., Cho, K., & Kim, M. (2020). Preservice physical education teacher’s development of adaptive competence. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 40(4), 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeichner, K. (2012). The turn once again toward practice-based teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 63(5), 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).