Abstract

Kindergarten teachers’ performance at work has important implications for the quality of early childhood education and the development of children. Therefore, promoting teachers’ work performance is of interest to kindergarten managers and policymakers. Evidence suggests that professional development opportunities may play an important role in understanding employees’ work performance. However, the possible mechanism underlying the relationship between professional development opportunities and work performance remains underexplored, especially among kindergarten teachers. This cross-sectional study examined whether professional commitment and work engagement mediated the association of professional development opportunities with work performance among Chinese kindergarten teachers. Online questionnaire data were collected from 336 kindergarten teachers working in Hong Kong, China (mean age = 31.6 years; 86% of them were women). Kindergarten teachers rated the availability of professional development opportunities and their work performance. They also rated their professional commitment (indicated by affective, continuance, and normative commitment) and work engagement (indicated by vigor, dedication, and absorption). Structural equational modeling revealed that both professional commitment and work engagement uniquely mediated the association between professional development opportunities and work performance. The findings illustrated how professional development opportunities may enhance work performance by motivating teachers at the affective/cognitive and the behavioral levels. The findings also pointed to the potential utility of supporting the work performance of kindergarten teachers by providing them with ample professional development opportunities and promoting their professional commitment and work engagement.

1. Introduction

Early childhood education may promote children’s school readiness and facilitate their development (Lipscomb et al., 2022). As the caregivers and educators of young children, kindergarten teachers’ performance at work is crucial to the quality of early childhood education and children’s learning (Kusumawati, 2023). Therefore, the work performance of kindergarten teachers is of interest to not only parents and kindergarten managers but also policymakers and broader society. Although prior studies have linked job resources such as professional development opportunities (PDOs) to employees’ work performance (Mduma & Mkulu, 2021), few have examined such links among kindergarten teachers. Moreover, the possible mechanism underlying the relationship between PDOs and work performance remains underexplored (Egert et al., 2020). Guided by the job demands–resources theory (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017), a framework stemming from industrial-organizational psychology that can be readily used to analyze school practices and teacher well-being (Granziera et al., 2021), this cross-sectional study examined whether PDOs were associated with work performance among Chinese kindergarten teachers and whether the association was simultaneously mediated by professional commitment and work engagement.

1.1. PDOs and Work Performance

PDOs refer to formal and informal opportunities provided by an organization that help employees acquire new knowledge, hone professional skills, build social networks, cultivate work-related competence, or contribute to personal growth (Contreras et al., 2021). PDOs can come in different forms, including seminars, workshops, programs, resource libraries, job shadowing, peer learning, mentor coaching, and informal exchanges about news and techniques (Allehyani, 2023). According to the job demands–resources theory (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017), job resources involve “physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that are functional in achieving work goals, reduce job demands, and the associated physiological and psychological costs, or stimulate personal growth, learning, and development” (p. 274). PDOs are job resources, as they may—at least theoretically—increase employees’ work motivation (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014), allow them to cope with job demands more effectively (Molino et al., 2013), and contribute to positive work-related outcomes (Buettner et al., 2016; Byun & Jeon, 2023; Grant et al., 2019).

Indeed, there is evidence indicating that PDOs may be linked with work performance. For example, in a cross-sectional study with employees from small and medium-sized companies in South Korea, Y. Park and Choi (2016) found that PDOs (in the form of formal learning, such as training, and informal learning, such as meetings) were associated with work performance. Moreover, in a cross-sectional study with government employees in Nigeria, Tabiu et al. (2020) found that PDOs (in the form of in-house training) were associated with work performance. In addition, in a cross-sectional study with Pakistani and U.S. university employees, Saleem and Amin (2013) and Truitt (2011) found that PDOs (in the form of coaching, mentoring, training, and networking opportunities) were associated with work proficiency. Finally, in a cross-sectional study with Japanese high school teachers, Thahir et al. (2021) found that PDOs (in the form of need analyses and participation support) were linked with teaching performance. Therefore, kindergarten teachers with more PDOs were hypothesized to have better work performance.

1.2. The Mediating Role of Professional Commitment

Professional commitment refers to employees’ loyalty, dedication, and sense of responsibility toward their profession (Lestari et al., 2021). Professional commitment comprises three components: affective, continuance, and normative commitment (Meyer et al., 1993). Affective commitment refers to employees’ attachment to, feelings about, and identification with the profession. Employees with high affective commitment often feel proud of their profession and center their identities around it. Continuance commitment refers to employees staying in their profession based on their cost–benefit analyses. Employees with high continuance commitment often believe that it would cost too much to leave their profession. Normative commitment refers to employees’ perceived obligations to work in their profession. Employees with high normative commitment often have a strong sense of responsibility to stay in and contribute to their profession. Previous studies have linked professional commitment with better work performance among Jordanian nurses (Mrayyan & Al-Faouri, 2008), Filipino teachers (Esplana & Callo, 2024), and Taiwanese workers (Lin et al., 2022). This may not be surprising, as more committed employees are more likely to invest time and effort in their work and strive for excellence (Lestari et al., 2021). In fact, early childhood education studies have indicated that more committed kindergarten teachers in South Korea may provide more support to children, create higher-quality learning environments, and make a larger contribution to the community (Buettner et al., 2016; Byun & Jeon, 2023).

According to the job demands–resources theory (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017), job resources improve work performance by instigating a motivating process. Continued professional development in one field—which invariably entails employees’ investment of time and effort (Mlambo et al., 2021)—may increase employees’ senses of competence and obligations and thus work performance (Yang et al., 2017). In fact, prior research has linked PDOs to higher commitment to the profession among Chinese part-time faculty members (K. S. Li et al., 2013), Indonesian elementary school teachers (Asiyah et al., 2021), and Chinese workers (Jun-Jia & Ming-Hua, 2022). It is noteworthy, however, that null findings have also been reported. For example, in a cross-sectional study with nurses from the U.K., Drey et al. (2009) found that mandatory training was not associated with professional commitment.

Only a handful of studies have examined the potential mediating role of professional commitment in the relationship between job resources and work performance. For example, in a cross-sectional study with employees from information technology companies in Taiwan, professional commitment mediated the relationship of positive organizational interactions with work performance (Lin et al., 2022). Moreover, in a cross-sectional study with Filipino teachers, professional commitment partially mediated the relationship of collaborative workplace culture with work performance (Esplana & Callo, 2024). To the best of our knowledge, no prior studies have examined the interrelationships among professional commitment, PDOs, and work performance. However, positive organizational interactions, collaborative workplace culture, and PDOs are all job resources that may motivate employees and improve their work performance (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). Therefore, professional commitment was hypothesized to mediate the relationship of PDOs with work performance among Chinese kindergarten teachers.

1.3. The Mediating Role of Work Engagement

Work engagement refers to employees’ intense involvement and complete absorption in a work-related task that is both challenging and enjoyable (Bakker et al., 2020). Work engagement may comprise three components: vigor, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli et al., 2002). Vigor refers to employees’ high levels of energy, enthusiasm, and willingness at work. Vigorous employees are often passionate and excited about their work. Dedication refers to employees’ senses of pride, significance, and responsibility. Dedicated employees often see the value of their profession and are eager to contribute to their organizations. Absorption refers to employees’ satisfaction with and immersion in their work. Absorbed employees often experience a flow-like state and get “carried away” while working. Evidence suggests that more engaged employees are more likely to experience positive emotions, seek support from their colleagues and feedback from their supervisors, and aim for the highest quality of work (Corbeanu & Iliescu, 2023). Furthermore, highly engaged employees—such as from American public service sectors (Scrimpshire et al., 2023), Romanian private companies (Tisu et al., 2020), and Peruvian call centers (Gabel Shemueli et al., 2021)—tend to show better work performance.

As elaborated by Bakker and Demerouti (2017), job resources may promote employees’ work engagement by providing them with intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. For example, PDOs may help employees learn and grow, fulfilling their basic needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competence (Deci et al., 2017). PDOs may also help employees achieve work-related goals and gain social and tangible rewards (e.g., praise and awards). Indeed, PDOs have been linked to work engagement among Colombian nurses (Contreras et al., 2021), Chinese workers (Jun-Jia & Ming-Hua, 2022), and Nepalese workers (Niraula & Kharel, 2023).

Corroborating such views, previous studies have identified work engagement as a mediator in the relationship between job resources and work performance. For example, in a cross-sectional study with employees from Italian companies, work engagement mediated the link of positive supervisor behaviors with work performance (De Carlo et al., 2020). Moreover, in a longitudinal study with Taiwanese nurses, work engagement mediated the link of transformational leadership with task performance (Lai et al., 2020). Little research on this topic has been conducted with teachers, but one cross-sectional study demonstrated that work engagement mediated the link of positive organizational culture with work performance among Malaysian faculty members (Abdullahi et al., 2021). Therefore, work engagement was hypothesized to mediate the association of PDOs with work performance among Chinese kindergarten teachers.

1.4. The Present Study

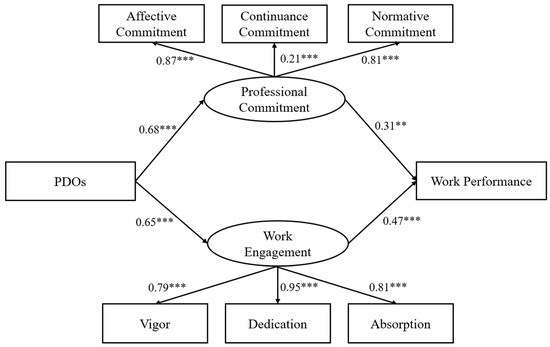

To recap, whether and why PDOs may be associated with work performance remains underexplored among kindergarten teachers. Therefore, guided by the job demands–resources theory (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017), the present study examined whether PDOs were linked with work performance and whether professional commitment and work engagement mediated such an association among Chinese kindergarten teachers (see Figure 1 for a conceptual diagram).

Figure 1.

Standardized path coefficients of a structural equational model linking professional development opportunities (PDOs) to work performance among Chinese kindergarten teachers. Note: ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedures

Participants were 336 full-time kindergarten teachers working in Hong Kong, China. An online poster detailing the study’s aims and procedures was emailed to all in-service kindergarten teachers studying at a public university in Hong Kong. The university has been providing early childhood education programs for decades and has trained more than 80% of all kindergarten teachers in Hong Kong. The online poster was also posted on education-related forums and social media platforms. Participants would be directed to the study’s questionnaire page after clicking on the poster. Participants then provided informed consent and rated questions on their working experiences and provided demographic information. Participants received a supermarket coupon of HKD 50 (about USD 6) as a token of appreciation after completing the questionnaire. We opted to use an online questionnaire given ethical consideration: Compared to a paper-and-pencil questionnaire, an online questionnaire provides participants with a stronger sense of security and reduces their worry about being identified (Riggle et al., 2005). In fact, an online questionnaire typically incorporates more robust security measures and involves a lower risk of unauthorized access—either by hijackers or persons with potential conflict of interest (Chang & Vowles, 2013), such as the supervisors in our case. The procedures were approved by The Education University of Hong Kong’s Human Research Ethics Committee.

Participants had an average age of 31.6 years (SD = 21.2), and 86% of them were women. Their teaching experience varied; three percent had worked as kindergarten teachers for less than 1 year, 49% for 1 to 5 years, 32% for 5 to 10 years, and 16% for more than 10 years.

2.2. Measures

Variables were assessed using validated measures. The measures were presented in Chinese in the questionnaire. Two translators independently forward- and backward-translated the measures from English to Chinese. A third translator then checked the work, resolved the discrepancies, and finalized the Chinese items. Ratings for each measure were averaged, such that higher scores indicated higher levels of the construct.

PDOs were assessed using the 3-item subscale of possibilities of professional development from the Job Resources Scale (Mastenbroek et al., 2014). On a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree), teachers rated the availability of PDOs in their current kindergartens (e.g., “My work offers me the opportunity to learn new things” and “In my work, I have sufficient opportunities to develop my strong points”). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.83.

Professional commitment was assessed using the 9-item subscale of the Affective, Continuance, and Normative Organizational and Professional Commitment Scales (McInerney et al., 2015). On a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree), teachers rated their commitment to the teaching profession, including affective commitment (three items, e.g., “Being in the teaching profession is important to my self-image”), continuance commitment (three items, e.g., “Too much of my life will be disrupted if I were to change my profession”), and normative commitment (three items, e.g., “I feel a responsibility to the teaching profession to continue in it”). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.83, 0.79, and 0.83, for affective, continuance, and normative commitment, respectively.

Work engagement was assessed using the 9-item UTECH Work Engagement Scale (Schaufeli et al., 2006). On a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree), teachers rated their engagement with their work, including vigor (three items, e.g., “At my work, I feel bursting with energy”), dedication (three items, e.g., “My job inspires me”), and absorption (two items, e.g., “I feel happy when I am working intensely”). One item from the absorption subscale was removed to improve its Cronbach’s alpha. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89, 0.84, and 0.76, for vigor, dedication, and absorption, respectively.

Work performance was assessed using the 5-item Teachers’ Perceptions of Work Performance Scale (Cheng et al., 2013). On a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree), teachers rated their work performance (e.g., “I think that I have a diligent work attitude and outstanding performance” and “The kindergarten principal is satisfied with my work performance”). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.86.

2.3. Data Analyses

First, the research team computed the means and standard deviations of and correlations among variables using SPSS 29. Second, the team conducted structural equational modeling using Jamovi Statistical Data Analysis 2.3.24, examining whether work engagement (indicated by vigor, dedication, and absorption) and professional commitment (indicated by affective, continuance, and normative commitment) mediated the association of PDOs with work performance. Initial analyses indicated that age, gender, and years of working experience were not correlated with PDOs or work performance (rs ranging from 0.01 to 0.30, n.s.). Therefore, these demographic variables were not controlled for in the structural equational model. The team evaluated the model–data fit with the Chi-square test (χ2), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker Lewis index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). CFI and TLI values close to or larger than 0.95, RMSEA values close to 0.06, and SRMR values close to or smaller than 0.08 indicate an excellent fit between the hypothesized model and the observed data (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

3. Results

Table 1 shows the means and standard deviations of and correlations among variables. PDOs were correlated positively with affective and normative commitments, vigor, dedication, and absorption, and work performance (rs ranging from 0.49 to 0.62, ps < 0.001). Moreover, vigor, dedication, and absorption were correlated positively with work performance (rs ranging from 0.56 to 0.70, ps < 0.001), whereas affective, continuance, and normative commitments were correlated positively with work performance (rs ranging from 0.14 to 0.55, ps < 0.001).

Table 1.

Means (Ms) and standard deviations (SDs) of and correlations among variables.

Figure 1 shows the standardized coefficients of the structural equational model. Table 2 shows the unstandardized coefficients and standard errors of all direct and indirect effects. The results indicated that PDOs were positively associated with professional commitment (β = 0.68, SE = 0.10, p < 0.001), and professional commitment was positively associated with work performance (β = 0.31, SE = 0.05, p < 0.01). Moreover, PDOs were positively associated with work engagement (β = 0.65, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001), and work engagement was positively associated with work performance (β = 0.47, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001). Analyses of the indirect effects revealed that both professional commitment (β = 0.21, SE = 0.06, p < 0.01) and work engagement (β = 0.30, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001) mediated the association of PDOs with work performance. Overall, the model demonstrated an excellent fit with the data (X2(14) = 25.1, p < 0.05; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.05; SRMR = 0.02). Moreover, the model explained 57% of the variance in work performance, indicating a large effect size (Cohen, 1988).

Table 2.

Unstandardized path coefficients (B), standard errors (SE), and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of a structural equational model linking professional development opportunities (PDOs) to work performance among Chinese kindergarten teachers.

4. Discussion

Kindergarten teachers play an irreplaceable role in ensuring the quality of early childhood education and promoting the development of young children. Therefore, it is crucial to understand how kindergartens and policymakers may improve kindergarten teachers’ work performance. In keeping with the existing literature (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Golbodaghi, 2024; Lee et al., 2017; Thahir et al., 2021), which is mostly based on non-teachers’ experience (Granziera et al., 2021), our results indicated that professional commitment and work engagement uniquely mediated the association between PDOs and work performance. Our findings illustrated how PDOs, as job resources, may enhance kindergarten teachers’ work performance by motivating them at the affective/cognitive and the behavioral level. Our findings also pointed to the potential utility of supporting the work performance of kindergarten teachers by providing them with ample PDOs and targeting their professional commitment and work engagement.

4.1. Professional Commitment and Work Engagement as Unique Mediators

According to the job demands–resources theory (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017), PDOs may instigate a motivating process that helps employees achieve work-related goals, reduce job demands, or stimulate learning and growth. Such a motivating process may involve different factors, some more affective/cognitive (e.g., professional commitment), some more behavioral (e.g., work engagement). The unique contribution of our study lies in our inclusion of both professional commitment and work engagement in the same analytical model and in our focus on kindergarten teachers, a profession known to be associated with high physical, social, emotional, and pedagogical demands (Kwon et al., 2021; Zheng et al., 2024). This may be particularly relevant here, given that motivating factors are often moderately to strongly correlated, as in our and other studies (Jun-Jia & Ming-Hua, 2022), and that job resources may gain motivating potential and become extra impactful when job demands are high (Bunjak et al., 2023). Therefore, additional research should be directed at examining whether the strength of the interrelationships among PDOs, professional commitment, work engagement, and work performance may vary as a function of work demands. More generally, however, our study demonstrated the utility of “borrowing” the work from one field to broaden our understanding of another. Future early childhood education researchers may consider using the job demands–resources theory (Becker et al., 2017) to guide their studies.

It is worth noting that, despite our large effect size, our model did not explain all variance in work performance, suggesting that kindergarten teachers’ work performance may be shaped by factors not assessed in this study. A more comprehensive approach may be used to examine, for example, how different job resources, such as collaborative workplace culture, transformational leadership, positive organizational interactions, and PDOs, may uniquely contribute to the work performance of kindergarten teachers.

Our findings have important practical implications: Kindergarten managers and policymakers may provide teachers with more PDOs and promote teachers’ professional commitment and work engagement as means to improve the work performance of teachers. Possible strategies to optimize PDOs may include providing a wide range of initiatives, offering incentives to encourage teachers to participate in professional development activities, and maintaining a flexible training schedule to accommodate teachers’ needs (Allehyani, 2023). Possible strategies to enhance professional commitment may include introducing teacher-friendly policies and cultivating a sense of pride among teachers. For example, allowing greater flexibility in personal leave and work hours may help teachers balance their professional and personal lives (Byun & Jeon, 2023). Highlighting their contributions to nurturing children may also improve teachers’ self-images (Byun & Jeon, 2023). Meanwhile, possible strategies to enhance work engagement may include offering various job resources, such as supervisor support and performance feedback (J. Park et al., 2022), promoting positive emotions in the workplace, using transformational leadership to instill inspiration among teachers, and arranging enjoyable but challenging tasks for teachers (Vîrgă et al., 2021).

4.2. Limitations and Conclusions

This study was not without limitations. First, participants were recruited via emails sent to in-service kindergarten teachers studying in one university and posters posted on education-related forums and social media platforms. Although more than 80% of early childhood educators in Hong Kong had received training from this university, the generalizability of our findings to the larger population of kindergarten teachers remains unknown. Additionally, given the limitations of time and resources available, participants’ identities could not be verified with, for example, confirmation letters from their employers. Therefore, our hypotheses should be retested using representative samples recruited via random sampling methods, ideally through actual kindergartens. Second, this study used generic measures of PDOs and work performance. Instead of asking participants to rate, for example, whether formal PDOs (e.g., seminars, workshops, and programs) and informal PDOs (e.g., meetings and everyday exchanges) were provided (Richter et al., 2014), in a mandatory or self-directed manner (Drey et al., 2009), the team asked participants to rate whether there were opportunities for growth and development in general. Similarly, instead of asking participants to rate, for example, their performance in such aspects as pedagogical skills, classroom management techniques, abilities to cater for child diversity, and experience with children and their parents (Y. L. J. Li, 2003), the team asked participants to rate whether they did well at work in general. An important direction for future research is to use a more nuanced, more multidimensional approach to measure both PDOs and work performance.

Third, since both the predictor and outcome variables were based on data reported by a common reporter, our findings might have been affected by social desirability and common method variance. To improve internal validity, future studies may consider indicating a latent construct using data collected using multiple methods (e.g., using both subjective and objective measures to assess the availability of PDOs). Future studies may also consider linking variables assessed using one method from one informant (e.g., self-reports of professional commitment using questionnaires) to variables assessed using another method from another informant (e.g., independent observations of kindergarten teachers’ teaching performance). Finally, our study was directed by theory (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017) and research (Golbodaghi, 2024; Lee et al., 2017; Thahir et al., 2021) that had conceptualized PDOs, professional commitment, and work engagement as driving forces of work performance. However, definitive claims about causation cannot be made based on cross-sectional data. Our findings could be interpreted to mean, for example, that more competent kindergarten teachers were more committed to the profession, more enthusiastic about their work, and more likely to plead for PDOs. Longitudinal studies should be conducted to investigate whether PDOs may sequentially predict professional commitment, work engagement, and work performance among kindergarten teachers. Future experimental studies should be conducted to examine whether providing kindergarten teachers with more PDOs may improve their professional commitment, work engagement, and work performance.

In the face of these limitations, this study extended the literature by examining whether PDOs were associated with work performance among Chinese kindergarten teachers and whether such an association was mediated by professional commitment and work engagement. Theoretically, our findings underscored the possible role of PDOs in understanding kindergarten teachers’ affective/cognitive and behavioral motivation and work performance. Practically, our findings highlighted the potential utility of supporting the work performance of kindergarten teachers by providing them with ample PDOs and promoting their professional commitment and work engagement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.-Y.L. and C.-B.L.; methodology, T.-Y.L. and C.-B.L.; data analysis, T.-Y.L. and C.-B.L.; writing—original draft preparation, T.-Y.L.; writing—review and editing, C.-B.L.; supervision, C.-B.L.; project administration, T.-Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of The Education University of Hong Kong (Ref. no. 2022-2023-0220) (Date of approval: 29 December 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdullahi, M. S., Raman, K., & Solarin, S. A. (2021). Effect of organizational culture on employee performance: A mediating role of employee engagement in malaysia educational sector. International Journal of Supply and Operations Management, 8(3), 232–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allehyani, H. S. (2023). Facing forward: Obstacles and implications for kindergarten teachers’ professional development. International Journal of Modern Education Studies, 7(2), 596–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiyah, S., Wiyono, B. B., Hidayah, N., & Supriyanto, A. (2021). The effect of professional development, innovative work and work commitment on quality of teacher learning in elementary schools of Indonesia. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 2021(95), 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., Petrou, P., Op den Kamp, E. M., & Tims, M. (2020). Proactive vitality management, work engagement, and creativity: The role of goal orientation. Applied Psychology, 69(2), 351–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, B. D., Gallagher, K. C., & Whitaker, R. C. (2017). Teachers’ dispositional mindfulness and the quality of their relationships with children in Head Start classrooms. Journal of School Psychology, 65, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buettner, C. K., Jeon, L., Hur, E., & Garcia, R. E. (2016). Teachers’ social-emotional capacity: Factors associated with teachers’ responsiveness and professional commitment. Early Education and Development, 27(7), 1018–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunjak, A., Černe, M., Nagy, N., & Bruch, H. (2023). Job demands and burnout: The multilevel boundary conditions of collective trust and competitive pressure. Human Relations, 76(5), 657–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, S., & Jeon, L. (2023). Early childhood teachers’ work environment, perceived personal stress, and professional commitment in South Korea. Child & Youth Care Forum, 52(5), 1019–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T. Z. D., & Vowles, N. (2013). Strategies for improving data reliability for online surveys: A case study. International Journal of Electronic Commerce Studies, 4(1), 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H. Y. K., Cheng, C. Y., & Ju, Y. Y. (2013). Work-related musculoskeletal disorders and ergonomic risk factors in early intervention educators. Applied Ergonomics, 44(1), 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, F., Abid, G., Govers, M., & Saman Elahi, N. (2021). Influence of support on work engagement in nursing staff: The mediating role of possibilities for professional development. Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración, 34(1), 122–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbeanu, A., & Iliescu, D. (2023). The link between work engagement and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 22(3), 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carlo, A., Dal Corso, L., Carluccio, F., Colledani, D., & Falco, A. (2020). Positive supervisor behaviors and employee performance: The serial mediation of workplace spirituality and work engagement. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deci, E. L., Olafsen, A. H., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annual review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drey, N., Gould, D., & Allan, T. (2009). The relationship between continuing professional education and commitment to nursing. Nurse Education Today, 29(7), 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egert, F., Dederer, V., & Fukkink, R. G. (2020). The impact of in-service professional development on the quality of teacher-child interactions in early education and care: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 29, 100309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esplana, J. E. V., & Callo, E. C. (2024). Workplace culture and environment towards teacher’s performance: The mediating role of professional commitment. TWIST, 19(3), 313–322. [Google Scholar]

- Gabel Shemueli, R., Sully de Luque, M. F., & Bahamonde, D. (2021). The role of leadership and engagement in call center performance: Answering the call in Peru. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 42(2), 265–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golbodaghi, A. (2024). The influence of professional coaching on job performance: The mediating effects of work meaningfulness and work engagement (Order No. 31142255). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global A&I: The Sciences and Engineering Collection (3037345054). Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/influence-professional-coaching-on-job/docview/3037345054/se-2 (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Grant, A. A., Jeon, L., & K Buettner, C. (2019). Chaos and commitment in the early childhood education classroom: Direct and indirect associations through teaching efficacy. Teaching and Teacher Education, 81, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granziera, H., Collie, R., & Martin, A. (2021). Understanding teacher wellbeing through job demands-resources theory. In C. F. Mansfield (Ed.), Cultivating teacher resilience (pp. 229–244). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumawati, E. (2023). Analysis of the relationship between the school principal’s visionary leadership and kindergarten teachers’ performance. Journal of Innovation in Educational and Cultural Research, 4(1), 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K. A., Ford, T. G., Jeon, L., Malek-Lasater, A., Ellis, N., Randall, K., Kile, M., & Salvatore, A. L. (2021). Testing a holistic conceptual framework for early childhood teacher well-being. Journal of School Psychology, 86, 178–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, F. Y., Tang, H. C., Lu, S. C., Lee, Y. C., & Lin, C. C. (2020). Transformational leadership and job performance: The mediating role of work engagement. Sage Open, 10(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. M., Chou, M. J., Chin, C. H., & Wu, H. T. (2017). The relationship between psychological capital and professional commitment of preschool teachers: The moderating role of working years. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 5(5), 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, G. D., Izzati, U. A., Adhe, K. R., & Indriani, D. E. (2021). Professional commitment: Its effect on kindergarten teachers’ organizational citizenship behavior. Cypriot Journal of Educational Science, 16(4), 2037–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K. S., Tong, C., & Wong, A. (2013). The impact of career development on employee commitment of part-time faculty (PTF) in Hong Kong’s continuing professional development (CPD) sector. British Journal of Education, Society & Behavioural Science, 4(1), 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. L. J. (2003). What makes a good kindergarten teacher? A pilot interview study in Hong Kong. Early Child Development and Care, 173, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. P., Liu, C. M., & Chan, H. T. (2022). Developing job performance: Mediation of occupational commitment and achievement striving with competence enhancement as a moderator. Personnel Review, 51(2), 750–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipscomb, S. T., Chandler, K. D., Abshire, C., Jaramillo, J., & Kothari, B. (2022). Early childhood teachers’ self-efficacy and professional support predict work engagement. Early Childhood Education Journal, 50(4), 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastenbroek, N. J. J. M., Demerouti, E., van Beukelen, P., Muijtjens, A. M. M., Scherpbier, A. J. J. A., & Jaarsma, A. D. C. (2014). Measuring potential predictors of burnout and engagement among young veterinary professionals: Construction of a customised questionnaire (the Vet-DRQ). Veterinary Record, 174(7), 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInerney, D. M., Ganotice, F. A., Jr., King, R. B., Marsh, H. W., & Morin, A. J. (2015). Exploring commitment and turnover intentions among teachers: What we can learn from Hong Kong teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 52, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mduma, E. R., & Mkulu, D. G. (2021). Influence of teachers’ professional development practices on job performance in public secondary schools: A case of Nyamagana District, Mwanza-Tanzania. International Journal of English Literature and Social Sciences, 6(1), 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., & Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(4), 538–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlambo, M., Silén, C., & McGrath, C. (2021). Lifelong learning and nurses’ continuing professional development, a metasynthesis of the literature. BMC Nursing, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molino, M., Ghislieri, C., & Cortese, C. G. (2013). When work enriches family-life: The mediational role of professional development opportunities. Journal of Workplace Learning, 25(2), 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrayyan, M. T., & Al-Faouri, I. (2008). Nurses’ career commitment and job performance: Differences between intensive care units and wards. Journal of Research in Nursing, 13(1), 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niraula, G. P., & Kharel, S. (2023). Human resource development and employee engagement in Nepalese development banks. Tribhuvan University Journal, 38(1), 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J., Han, S. J., Kim, J., & Kim, W. (2022). Structural relationships among transformational leadership, affective organizational commitment, and job performance: The mediating role of employee engagement. European Journal of Training and Development, 46(9), 920–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y., & Choi, W. (2016). The effects of formal learning and informal learning on job performance: The mediating role of the value of learning at work. Asia Pacific Education Review, 17, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, D., Kunter, M., Klusmann, U., Lüdtke, O., & Baumert, J. (2014). Professional development across the teaching career: Teachers’ uptake of formal and informal learning opportunities. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(1), 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggle, E. D., Rostosky, S. S., & Reedy, C. S. (2005). Online surveys for BGLT research: Issues and techniques. Journal of Homosexuality, 49(2), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, S., & Amin, S. (2013). The impact of organizational support for career development and supervisory support on employee performance: An empirical study from Pakistani academic sector. European Journal of Business and Management, 5, 194–207. Available online: https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/EJBM/article/view/4993/5084#google_vignette (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Taris, T. W. (2014). A critical review of the Job Demands-Resources Model: Implications for improving work and health. In G. F. Bauer, & O. Hämmig (Eds.), Bridging occupational, organizational and public health. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrimpshire, A. J., Edwards, B. D., Crosby, D., & Anderson, S. J. (2023). Investigating the effects of high-involvement climate and public service motivation on engagement, performance, and meaningfulness in the public sector. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 38(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabiu, A., Pangil, F., & Othman, S. Z. (2020). Does training, job autonomy and career planning predict employees’ adaptive performance? Global Business Review, 21(3), 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thahir, M., Komariah, A., Kurniady, D. A., Suharto, N., Kurniatun, T. C., Widiawati, W., & Nurlatifah, S. (2021). Professional development and job satisfaction on teaching performance. Linguistics and Culture Review, 54, 2507–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisu, L., Lupșa, D., Vîrgă, D., & Rusu, A. (2020). Personality characteristics, job performance and mental health: The mediating role of work engagement. Personality and Individual Differences, 153, 109644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truitt, D. L. (2011). The effect of training and development on employee attitude as it relates to training and work proficiency. Sage Open, 1(3), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vîrgă, D., Maricuţoiu, L. P., & Iancu, A. (2021). The efficacy of work engagement interventions: A meta-analysis of controlled trials. Current Psychology, 40(12), 5863–5880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. H., Fang, S. C., & Huang, C. Y. (2017). The mediating role of competency on the relationship between training and task performance: Applied study in pharmacists. International Journal of Business Administration, 8(7), 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zheng, X., Fu, J., & Peng, J. (2024). Exploring the relationships among display rules, emotional job demands, emotional labour and kindergarten teachers’ occupational well-being. European Journal of Education, 59(4), e12771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-J., & Song, H.-M. (2022). The impact of career growth on knowledge-based employee engagement: The mediating role of affective commitment and the moderating role of perceived organizational support. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 805208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).