A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of a Wellbeing Programme Designed for Undergraduate Students: Exploring Participants’ Experiences Using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- How effective is TTT for undergraduate students’ mental wellbeing?

- (2)

- How do students make sense of their experience with the TTT programme?

2. Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Recruitment

2.3. Participants

2.4. Programme Delivery

2.5. Measures and Data Collection

2.6. Data Analyses

2.6.1. Quantitative Arm

2.6.2. Qualitative Arm

3. Results

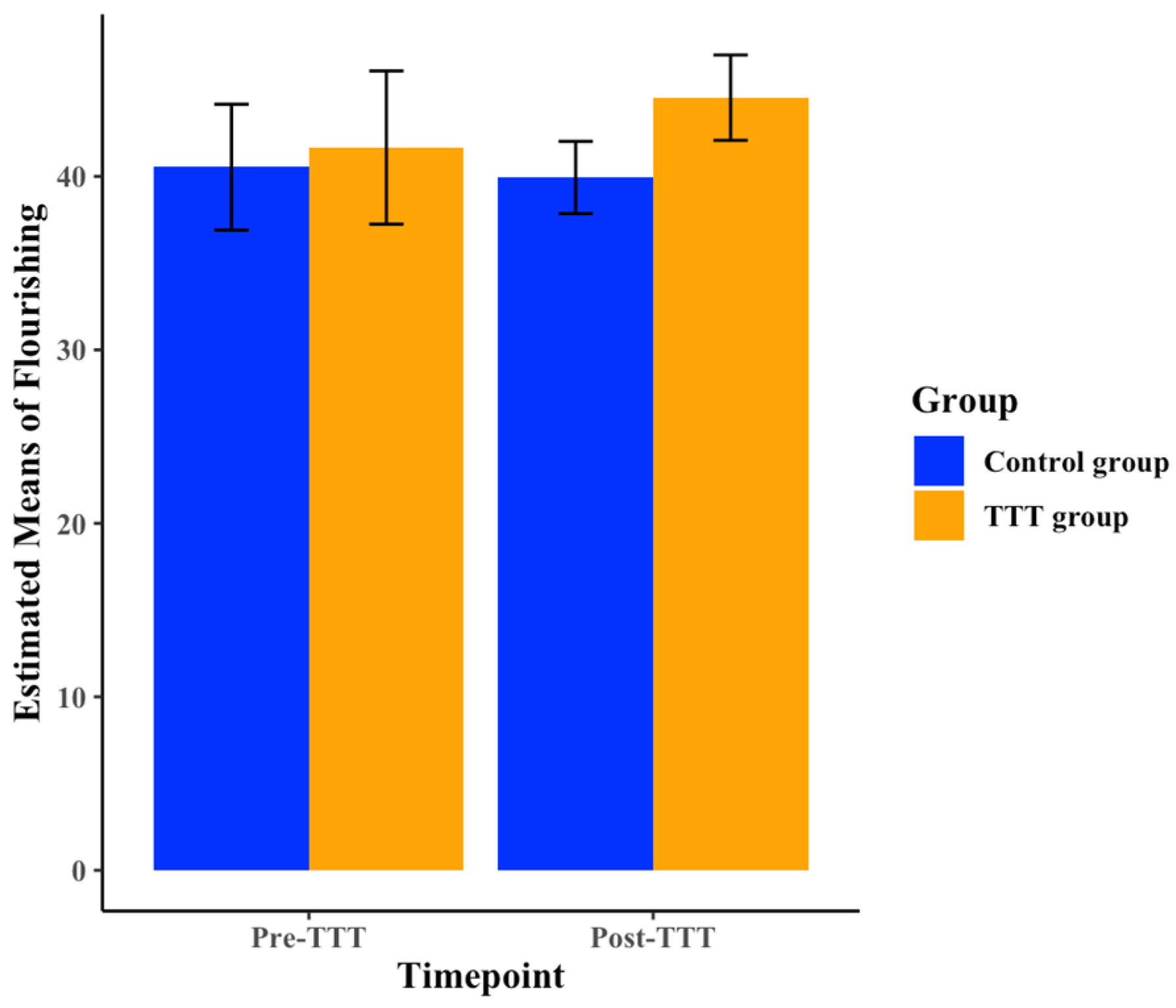

3.1. Quantitative Evaluation of TTT: Results from RCT

3.1.1. Effects on Psychological Wellbeing (FS)

3.1.2. Effects on Mental Wellbeing (SWEMWBS)

3.1.3. Effects on Resilience (BRS)

3.2. Feedback Survey Findings

3.3. IPA Findings: How Students Make Sense of Their TTT Experience

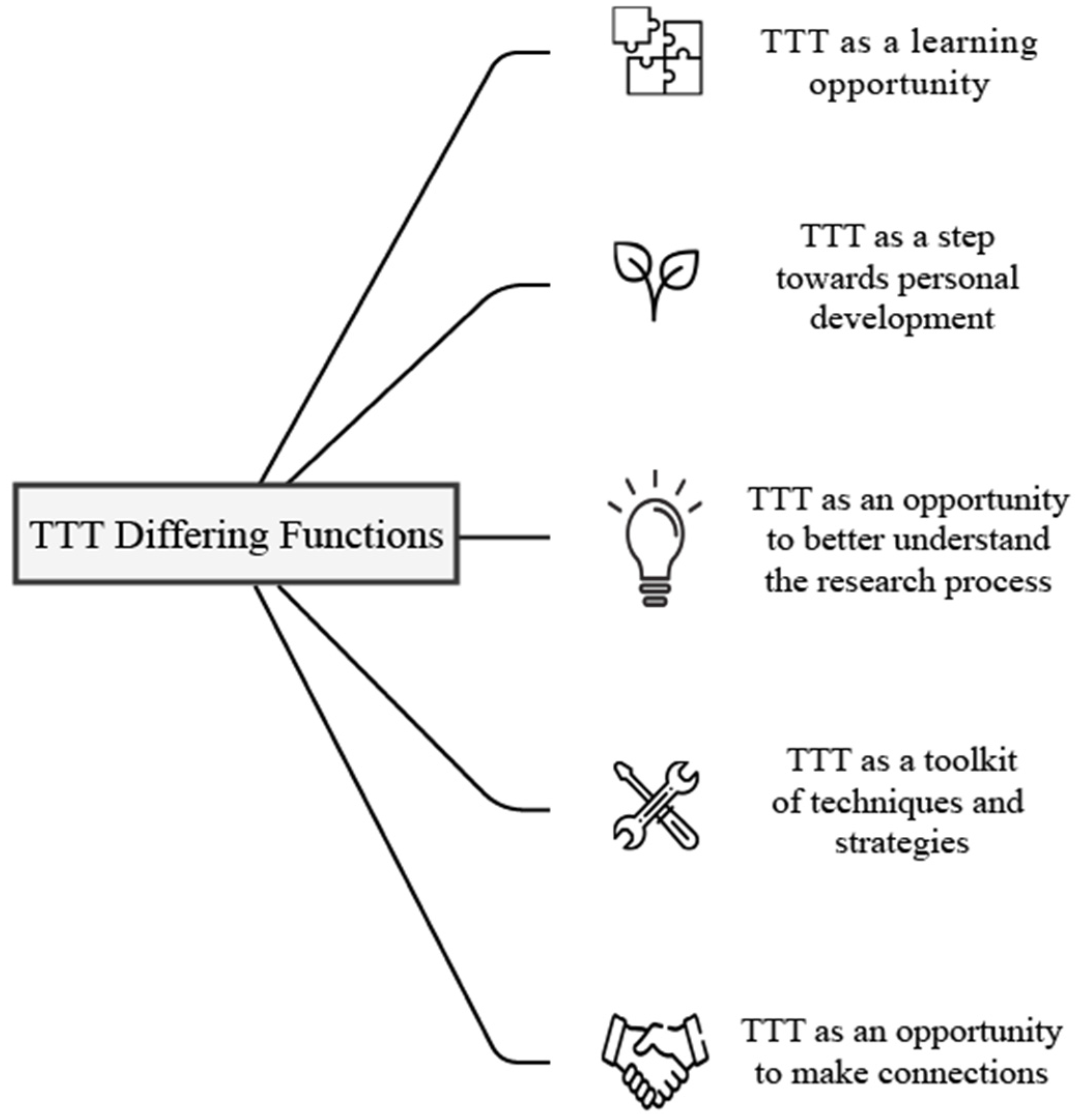

3.3.1. Differing Functions of TTT for the Student

Learning Opportunity

“It’s kind of related to culture, but you know, sometimes people are brought up with certain ideas of like they need to keep things to themselves or like stuff like that. Like something that mentions those kinds of things, so that it makes it easier for people to analyse themselves and like … something related to, um, gender stereotypes and like culture, like different cultures, like the type of beliefs that people tend to grow up with…there was one topic about conflict…but, like, with an extra one about, like, different mindsets and that could add…so that people are more able to understand each other. Like a kind of cultural competency thing.”(ans 18–21, pp. 4–5)

A Step Towards Personal Development

“I knew it was from King’s, so I knew it would be good … on the basis that my teacher said it was good, especially for self-developmental um things, and I have gone to my tutor for, you know, asking how to cope with stress and manage my time better. And so she said that this programme will help me do that.”(ans 28 & 30, p. 4)

Opportunity to Better Understand the Research Process

Toolkit of Techniques and Strategies

“My expectations were that it was going to be a programme that was self-paced online that would help my mental health and wellbeing in, you know, in a few different techniques that the researchers would recommend … I now have a few techniques that I can sort of instil in my everyday life … So I think I’ll definitely be using some of the techniques.”(ans 6–8, p. 2)

“I think I’ll use it in the future. I don’t know about, like, on a daily basis, but it, but um, I have like, when something is related to one of the topics comes up, I do sometimes remember the facts.”(ans 15, p. 3)

Opportunity to Make Connections

“If we can see you on, I think, your group, it would be much more, um, I will feel more close to you than just see the emails.”(ans 82, p. 16)

“It wasn’t like a task for us to finish and with a lot of these mindfulness books, it just seems so detached cause it’s on a book … like you can’t form that connection with the authors, but whereas in the lectures because we can hear your voice because we’ve seen a couple of you in the workshops and stuff it was easy to make that connection.”(ans 39–40, pp. 5–6)

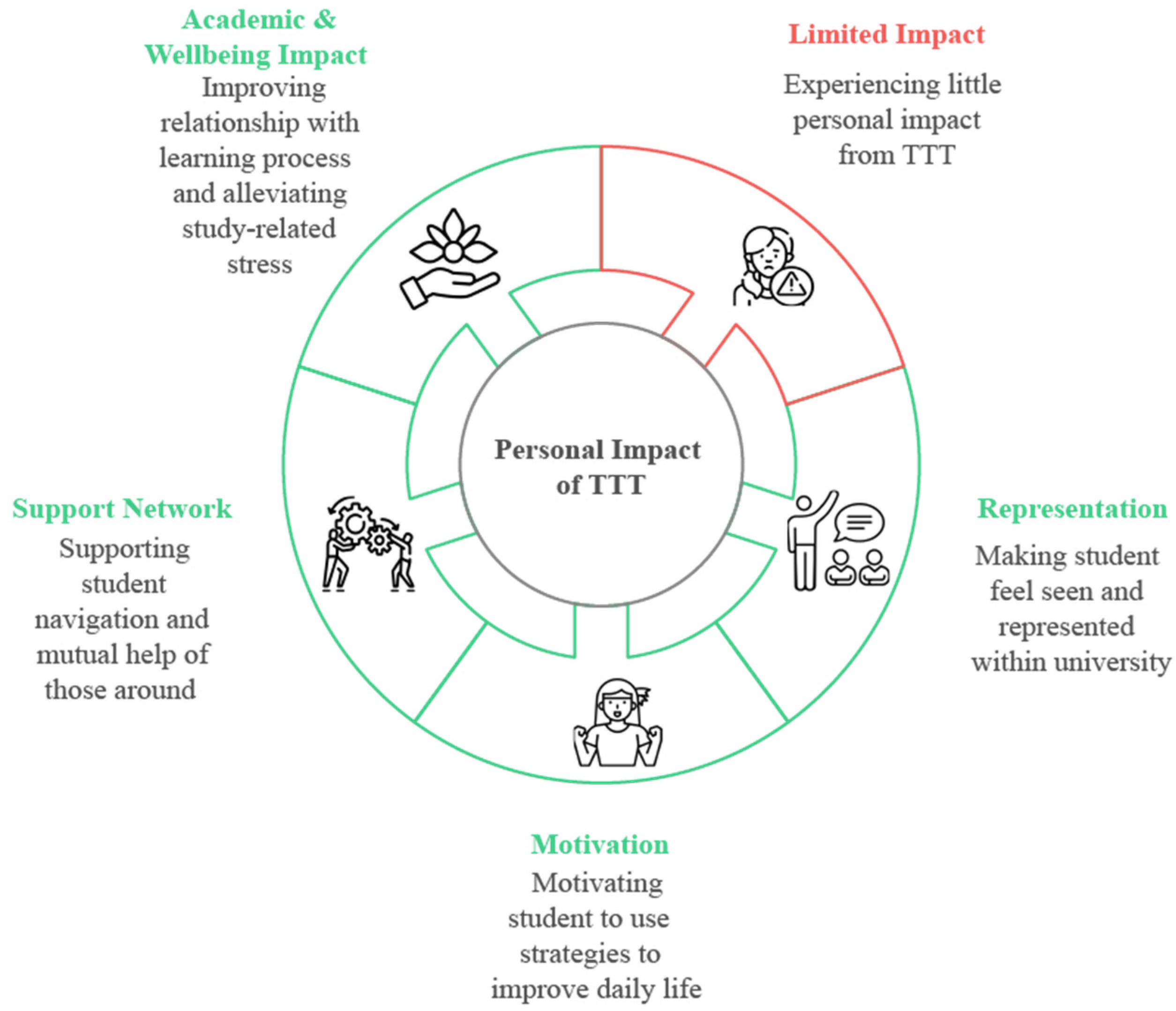

3.3.2. Personal Impact of TTT

“I’m very happy that I was given this opportunity because … it’s helped me (short pause) just not focus on the grades so much and just focus on the bigger things in life.”(ans 30, p. 4)

“It’s helped me a lot in terms of my own mental health, the mental health of others, like my family (ans 33, p. 5). Later on, to elaborate further, she added: So it wasn’t just focused on us. I like the fact that you guys focus on other people as well. Like looking after friends and family.”(ans 77, p. 12)

“And I don’t know if you’re [ethnolinguistic group]. Are you [ethnolinguistic group]? So, as soon as I saw your name, I was like ohh, there’s a [ethnolinguistic group] lecturer … I was so proud of you, and I was just like so happy that I could join this.”(ans 43, p. 6)

“I think everything I learned is very close to my problems, and as a first-year university student, those things were very helpful…. And of those information from the video, from take your message, and a meeting very close to my life. So I will do all those things, like er (pause), it changed my life demands. Let me show you. For example, I have a notebook to list what I should do, so I will not delay for, er, then, my plan but sometimes it will be, er, also to go relax or something.”(ans 20 & 25, pp. 5–6)

“Yeah, maybe some sort of of, um, yeah, strategies that may help to, like, stop procrastinating and, and boost productivity … But yeah, I think it was well in the programme anyway (ans 14, p. 4) or like I was able to keep track on it (what was going on during the programme) and it was fine because I think there were reminders … but maybe for some students who have a bit going on…”(ans 17, p. 5)

“I think it was delivered quite well, especially the topics being sort of split up into the different weeks and then also having the Teams channel and the in-person sessions, …, everything that I would think of has been thought about already and even some things I hadn’t thought about you guys already did.”(ans 15, p. 4)

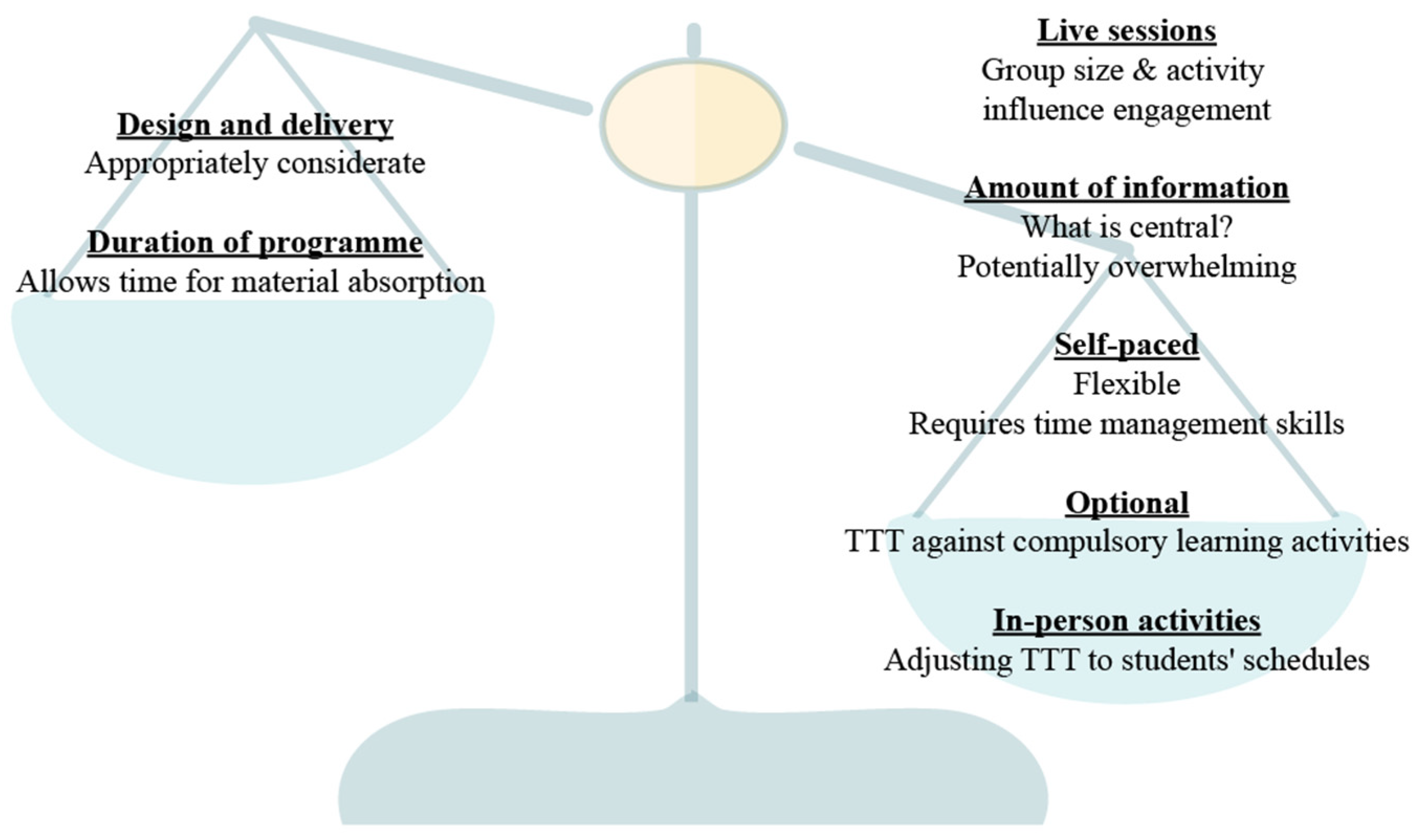

3.3.3. Placing Students Who Need It the Most at the Heart of TTT

“I think in terms of how the resources were, sort of, put up on the KEATS page, I wouldn’t say there were any sort of initial barriers because it had them, like I say, like, split up into the topics, but then also split up into what the resource is. But in terms of how the students may engage with them I would say perhaps, maybe the barriers may be that, um, they may find the, like, the plethora of resources could be maybe overwhelming to some students to see, like, a, a lot up there … I guess, um, reemphasising that, you know, these are optional for you if you want to go into further detail, but the videos are the main thing of, of this programme.”(ans 16, p. 5)

“What I would add on to that is it would be great if there was a poll beforehand that we can say what day or time, um, would have suited us and then maybe the majority, um, we could go with that… like 2 weeks in advance, um, could hopefully give enough time for you to organise it”(ans 9 & 20, pp. 3 & 8)

“I think if we have an online meeting every week like one hour or one hour and a half … So we don’t need to do it by ourselves … I think because for my type of people. Yeah, maybe we don’t, er, do this by ourself, but if there is something push us to do it, it would be very helpful.”(ans 12, 15, 16, p. 3–4)

“Uh, one thing like for me is that maybe I would think I should finish other modules coursework before the Time to Thrive… It’s maybe a little bit a problem…Maybe, just maybe because it’s not compulsory…from my understanding if something is not compulsory, I would be very lazy.”(ans 72–75, p. 14)

“I didn’t attend any of the, the live workshops they did, …the first few weeks I didn’t watch anything because I kept, like, forgetting… I think maybe, maybe it’s just the fact that it’s like, kind of like an optional thing, so people will tend to not prioritise it”(ans 22 & 25, pp. 5–6)

“Compared to other mindfulness and self-developing … this is more engaging because it is long-term… and we had a lot more time afterwards to go over the content, …, there’s no rush to the, to finish the content in that one week.”(ans 21–23, p. 3)

“I also think that smaller groups would help engage students better cause I’m the type, like, if there’s…more than 15 people in the Teams or Zoom meeting that I won’t say anything on the chat at all cause I’m such a shy person, but when there’s like 5 people, I tend to engage a lot more”(ans 65–67, p. 9)

“Maybe next time, you did not need you maybe cannot show those takeaway message before the seminar and on the seminar, you even could have, if there are more people, you can have some small group discussion. I don’t know if Teams have the breakout rooms … it could improve the attention and understand those things much more.”(ans 85–87, pp. 16–17)

4. Discussion

4.1. TTT’s Effectiveness on Student Wellbeing

4.2. The Differing Functions of TTT for the Student

4.3. Personal Impact of TTT

4.4. Placing Students Who Need It the Most at the Heart of TTT

4.5. Implications and Future Research

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Interview Protocol

- What motivated you to join the programme?

- As we explained to you before starting the recording, we know that some students have not engaged as we were hoping. But, if you have, what did you like the most and what didn’t you like about the programme?

- What were your expectations for the programme?

- How, if at all, do you think participating in Time to Thrive has impacted you?

- How, if at all, do you think you will use any information or skills that you have learned on Time to Thrive in your everyday life from now on or in the future?

- What would you change in Time to Thrive to make it more useful to you?

- Is there anything you would suggest we change about how our programme is delivered?

- Is there anything we didn’t cover that you would like to add, or any final comments you’d like to share?

References

- Abulfaraj, G. G., Upsher, R., Zavos, H. M. S., & Dommett, E. J. (2024). The impact of resilience interventions on university students’ mental health and well-being: A systematic review. Education Sciences, 14(5), 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R., Kannangara, C., & Carson, J. (2023). Long-term mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on university students in the UK: A longitudinal analysis over 12 months. British Journal of Educational Studies, 71(6), 585–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antaramian, S. (2015). Assessing psychological symptoms and well-being: Application of a dual-factor mental health model to understand college student performance. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 33(5), 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, R. P., Mortier, P., Bruffaerts, R., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Cuijpers, P., Demyttenaere, K., Ebert, D. D., Green, J. G., Hasking, P., Murray, E., Nock, M. K., Pinder-Amaker, S., Sampson, N. A., Stein, D. J., Vilagut, G., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Kessler, R. C. (2018). WHO world mental health surveys international college student project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127(7), 623–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J. S. L. (2018). Student mental health: Some answers and more questions. Journal of Mental Health, 27(3), 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruffaerts, R., Mortier, P., Kiekens, G., Auerbach, R. P., Cuijpers, P., Demyttenaere, K., Green, J. G., Nock, M. K., & Kessler, R. C. (2018). Mental health problems in college freshmen: Prevalence and academic functioning. Journal of Affective Disorders, 225, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, E. O., Kwok, I., Ludwig, A. B., Burton, W., Wang, X., Basti, N., Addington, E. L., Maletich, C., & Moskowitz, J. T. (2021). Interventions to improve well-being of health professionals in learning & work environments-original article. Global Advances in Health and Medicine, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, C. S., Travers, L. V., & Bryant, F. B. (2013). Promoting psychosocial adjustment and stress management in first-year college students: The benefits of engagement in a psychosocial wellness seminar. Journal of American College Health, 61(2), 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, E., Rands, H., Frommolt, V., Kain, V., Plugge, M., & Mitchell, M. (2018). Investigation of blended learning video resources to teach health students clinical skills: An integrative review. Nurse Education Today, 63, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, A. F., Brown, W. W., Anderson, J., Datta, B., Donald, J. N., Hong, K., Allan, S., Mole, T. B., Jones, P. B., & Galante, J. (2020). Mindfulness-based interventions for university students: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Applied Psychology. Health and Well-Being, 12(2), 384–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, G. P., Foster, J., & Zunszain, P. A. (2019). Time to flourish: Designing a coaching psychology programme to promote resilience and wellbeing in postgraduate students. European Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 3(7), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, G. P., Palmer, S., Egidio Nardi, A., & Venceslau Brás, A. (2017). Integrating positive psychology and the solution-focused approach with cognitive-behavioural coaching: The integrative cognitive-behavioural coaching model. European Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 1, 1–8. Available online: www.nationalwellbeingservice.com/journals (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Dias, G. P., Vourda, M.-C., Percy, Z., Bevilaqua, M. C. do N., Kandaswamy, R., Kralj, C., Strauss, N., & Zunszain, P. A. (2023). Thriving at university: Designing a coaching psychology programme to promote wellbeing and resilience among undergraduate students. International Coaching Psychology Review, 18(2), 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D. w., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97(2), 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, A., Ward, J. (Ed.), & Byrom, N. (2022). Measuring wellbeing in the student population. Available online: https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/207842571/Byrom_Dodd_measuring_wellbeing_in_the_student_population.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Dodd, A. L., Priestley, M., Tyrrell, K., Cygan, S., Newell, C., & Byrom, N. C. (2021). University student well-being in the United Kingdom: A scoping review of its conceptualisation and measurement. Journal of Mental Health, 30(3), 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, A. (2023). University student mental health: An important window of opportunity for prevention and early intervention. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 68(7), 495–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, D., Golberstein, E., & Hunt, J. B. (2009). Mental health and academic success in college. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 9(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, R., Fletcher, A., Giota, J., Eriksson, A., Thomas, B., & Bååthe, F. (2022). A flourishing brain in the 21st century: A scoping review of the impact of developing good habits for mind, brain, well-being, and learning. Mind, Brain, and Education, 16(1), 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellard, O. B., Dennison, C., & Tuomainen, H. (2023). Review: Interventions addressing loneliness amongst university students: A systematic review. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 28(4), 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmail, L. C., Barasky, R., Mittman, B. S., & Hickam, D. H. (2020). Improving comparative effectiveness research of complex health interventions: Standards from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(S2), 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, T. M., Bira, L., Gastelum, J. B., Weiss, T., & Vanderford, N. L. (2018). Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nature Biotechnology, 36, 282–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrer, L., Gulliver, A., Chan, J. K. Y., Batterham, P. J., Reynolds, J., Calear, A., Tait, R., Bennett, K., & Griffiths, K. M. (2013). Technology-based interventions for mental health in tertiary students: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(5), e101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, J., & Grant, A. M. (2003). Solution-focused coaching: Managing people in a complex world. Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Hariton, E., & Locascio, J. J. (2018). Randomised controlled trials—The gold standard for effectiveness research. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 125(13), 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hefferon, K., Ashfield, A., Waters, L., & Synard, J. (2017). Understanding optimal human functioning—The “call for qual” in exploring human flourishing and well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J., Cuthel, A. M., Lin, P., & Grudzen, C. R. (2020). Primary palliative care for emergency medicine (PRIM-ER): Applying form and function to a theory-based complex intervention. Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications, 18, 100570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjorth, C. F., Bilgrav, L., Frandsen, L. S., Overgaard, C., Torp-Pedersen, C., Nielsen, B., & Bøggild, H. (2016). Mental health and school dropout across educational levels and genders: A 4.8-year follow-up study. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, C., Hood, B., & Jelbert, S. (2022a). A systematic review of the effect of university positive psychology courses on student psychological wellbeing. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1023140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, C., Jelbert, S., Santos, L. R., & Hood, B. (2022b). Evaluation of a credit-bearing online administered happiness course on undergraduates’ mental well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE, 17(2), e0263514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, C., Jelbert, S., Santos, L. R., & Hood, B. (2024). Long-term analysis of a psychoeducational course on university students’ mental well-being. Higher Education, 88, 2093–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, B., Jelbert, S., & Santos, L. R. (2021). Benefits of a psychoeducational happiness course on university student mental well-being both before and during a COVID-19 lockdown. Health Psychology Open, 8(1), e2055102921999291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J., Nigatu, Y. T., Smail-Crevier, R., Zhang, X., & Wang, J. (2018). Interventions for common mental health problems among university and college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 107, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, G., & Spanner, L. (2019). The university mental health charter. Available online: https://www.studentminds.org.uk/uploads/3/7/8/4/3784584/191208_umhc_artwork.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Iasiello, M., van Agteren, J., & Cochrane, E. M. (2020). Mental health and/or mental illness: A scoping review of the evidence and implications of the dual-continua model of mental health. Evidence Base, 2020(1), 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. (2023). IBM SPSS statistics for mac. Version 29.0.2.0 [Computer software]. IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, K. E., & Brown, J. D. (2010). To friend or not to friend: Using new media for adolescent health promotion. North Carolina Medical Journal, 71(4), 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahu, E. R., Ashley, N., & Picton, C. (2022). Exploring the complexity of first-year student belonging in higher education: Familiarity, interpersonal, and academic belonging. Student Success, 13(2), 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R. C., Amminger, G. P., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Lee, S., & Bedirhan Ustun, T. (2007). Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry, 20(4), 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. L. M. (2014). Mental health as a complete state: How the salutogenic perspective completes the picture. In Bridging occupational, organizational and public health: A transdisciplinary approach (Vol. 9789400756403, pp. 179–192). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, M. S. (1975). Self-directed learning: A guide for learners and teachers. Association Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kounenou, K., Kalamatianos, A., Garipi, A., & Kourmousi, N. (2022). A positive psychology group intervention in Greek university students by the counseling center: Effectiveness of implementation. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, e965945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, L., Warren, M. A., Schwam, A., & Warren, M. T. (2023). Positive psychology interventions in the United Arab Emirates: Boosting wellbeing—And changing culture? Current Psychology, 42, 7475–7488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, C. F., Sandlund, M., Skelton, D. A., Altenburg, T. M., Cardon, G., Chinapaw, M. J. M., De Bourdeaudhuij, I., Verloigne, M., & Chastin, S. F. M. (2019). Framework, principles and recommendations for utilising participatory methodologies in the co-creation and evaluation of public health interventions. Research Involvement and Engagement, 5, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipson, S. K., Lattie, E. G., & Eisenberg, D. (2019). Increased rates of mental health service utilization by U.S. College students: 10-year population-level trends (2007–2017). Psychiatric Services, 70(1), 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomas, T., & Ivtzan, I. (2016). Second wave positive psychology: Exploring the positive–negative dialectics of wellbeing. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(4), 1753–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomas, T., Waters, L., Williams, P., Oades, L. G., & Kern, M. L. (2021). Third wave positive psychology: Broadening towards complexity. Journal of Positive Psychology, 16(5), 660–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A. J., Bottrell, D., Armstrong, D., Mansour, M., Ungar, M., Liebenberg, L., & Collie, R. J. (2015). The role of resilience in assisting the educational connectedness of at-risk youth: A study of service users and non-users. International Journal of Educational Research, 74, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R. E., & Ochsner, K. N. (2016). The neuroscience of emotion regulation development: Implications for education. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 10, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, S., & Gunnell, D. (2020). Trends in mental health, non-suicidal self-harm and suicide attempts in 16–24-year old students and non-students in England, 2000–2014. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55(1), 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A. L., Williams, L. M., & Silberstein, S. M. (2018). Found my place: The importance of faculty relationships for seniors’ sense of belonging. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(3), 594–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R. (2016). Neuroeducation: Integrating brain-based psychoeducation into clinical practice. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 38(2), 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, R. M., Horton, R. S., Vevea, J. L., Citkowicz, M., & Lauber, E. A. (2017). A re-examination of the mere exposure effect: The influence of repeated exposure on recognition, familiarity, and liking. Psychological Bulletin, 143(5), 459–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nation, M., Crusto, C., Wandersman, A., Kumpfer, K. L., Seybolt, D., Morrissey-Kane, E., & Davino, K. (2003). What works in prevention. Principles of effective prevention programs. The American Psychologist, 58(6–7), 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, J., He, A., Freeman, J., Stephenson, R., & Sotiropoulou, P. (2024). Student academic experience survey 2024. Available online: https://s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/assets.creode.advancehe-document-manager/documents/advance-he/Student%20Academic%20Experience%20Survey%202024_1718100686.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Neves, J., & Hewitt, R. (2020). student academic experience survey 2020. Available online: https://www.hepi.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/The-Student-Academic-Experience-Survey-2020.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Nolan, S. A., Cranney, J., de Souza, L. K., & Hulme, J. A. (2024). Centering psychological literacy in undergraduate psychology education internationally. Psychology Learning and Teaching, 23(2), 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özer, Ö., Köksal, B., & Altinok, A. (2024). Understanding university students’ attitudes and preferences for internet-based mental health interventions. Internet Interventions, 35, 100722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, S., & Szymanska, K. (2007). Cognitive behavioural coaching: An integrative approach. In S. Palmer, & A. Whybrow (Eds.), Handbook of coaching psychology: A guide for practitioners. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe, M. C., Dash, S., Klepac Pogrmilovic, B., Patten, R. K., & Parker, A. G. (2022). The engagement of tertiary students with an online mental health intervention during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: A feasibility study. Digital Health, 8, e20552076221117746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez Jolles, M., Lengnick-Hall, R., & Mittman, B. S. (2019). Core functions and forms of complex health interventions: A patient-centered medical home illustration. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 34(6), 1032–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perowne, R., Rowe, S., & Morrison Gutman, L. (2024). Understanding and defining young people’s involvement and under-representation in mental health research: A Delphi Study. Health Expectations, 27, e14102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Raeside, R., Jia, S. S., Redfern, J., & Partridge, S. R. (2022). Navigating the online world of lifestyle health information: Qualitative study with adolescents. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting, 5(1), e35165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafal, G., Gatto, A., & DeBate, R. (2018). Mental health literacy, stigma, and help-seeking behaviors among male college students. Journal of American College Health, 66(4), 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, S. M., Telford, N. R., Rickwood, D. J., & Parker, A. G. (2018). Young men’s access to community-based mental health care: Qualitative analysis of barriers and facilitators. Journal of Mental Health, 27(1), 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J. D., & Persky, A. M. (2020). Developing self-directed learners. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 84(3), 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar-Ouriaghli, I., Brown, J. S. L., Tailor, V., & Godfrey, E. (2020). Engaging male students with mental health support: A qualitative focus group study. BMC Public Health, 20(1), e1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakulku, J. (2011). The impostor phenomenon. The Journal of Behavioral Science, 6(1), 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Ten Have, M., Lamers, S. M. A., De Graaf, R., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2017). The longitudinal relationship between flourishing mental health and incident mood, anxiety and substance use disorders. The European Journal of Public Health, 27(3), 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrader, L. (2023). Focusing on the positive: An examination of the relationships between flourishing mental health, self-reported academic performance, and psychological distress in a national sample of college students [Doctoral dissertation, Middle Tennessee State University]. Middle Tennessee State University Digital Repository. Available online: https://jewlscholar.mtsu.edu/items/94e27ae8-3a41-47bf-a666-0ae337ae83ee (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Scott, F. J., & Willison, D. (2021). Students’ reflections on an employability skills provision. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 45(8), 1118–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sheu, H. B., & Sedlacek, W. E. (2004). An exploratory study of help-seeking attitudes and coping strategies among college students by race and gender. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 37(3), 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorey, S., Ang, E., Chua, J. Y. X., & Goh, P. S. (2022). Coaching interventions among healthcare students in tertiary education to improve mental well-being: A mixed studies review. In Nurse education today (Vol. 109). Churchill Livingstone. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2022). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J. A., & Osborn, M. (2003). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In J. A. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (pp. 51–80). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Spiers, J., & Riley, R. (2019). Analysing one dataset with two qualitative methods: The distress of general practitioners, a thematic and interpretative phenomenological analysis. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 16(2), 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics (J. B. Ullman, Ed.; 7th ed.). Pearson. Available online: https://www.pearsonhighered.com/assets/preface/0/1/3/4/0134790545.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Tennant, R., Hiller, L., Fishwick, R., Platt, S., Joseph, S., Weich, S., Parkinson, J., Secker, J., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2007). The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrana, A., Viglione, C., Rhee, K., Rabin, B., Godino, J., Aarons, G. A., Chapman, J., Melendrez, B., Holguin, M., Osorio, L., Gidwani, P., Juarez Nunez, C., Firestein, G., & Hekler, E. (2024). The core functions and forms paradigm throughout EPIS: Designing and implementing an evidence-based practice with function fidelity. Frontiers in Health Services, 3, 1281690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Health Minds Network. (2023). The healthy minds study: 2022–2023 data report. Available online: https://healthymindsnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/HMS_National-Report-2022-2023_full.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- van Gijn-Grosvenor, E. L., & Huisman, P. (2020). A sense of belonging among Australian university students. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(2), 376–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vourda, M. C., Bevilaqua, M. C. do N., du Preez, A., Kandaswamy, R., Kralj, C., Higgins, A., Williams, B. P., Zunszain, P. A., & Dias, G. P. (in press). Mental health and personal resourcefulness in adversity: A mixed-methods evaluation of a wellbeing program for university students in London. European Journal of Applied Positive Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, V., & James, T. (2020). Ants and pots: Do they change lives? Students perceptions on the value of positive psychology concepts. Student Success, 11(1), 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmore, J. (2002). Coaching for performance. Nicholas Brealey Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P. T. P. (2019). Second wave positive psychology’s (PP 2.0) contribution to counselling psychology. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 32(3–4), 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2022). Mental health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Worsley, J. D., Pennington, A., & Corcoran, R. (2022). Supporting mental health and wellbeing of university and college students: A systematic review of review-level evidence of interventions. PLoS ONE, 17(7), e0266725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, K., Akiyoshi, K., Kondo, H., Akioka, H., Teshima, Y., Yufu, K., Takahashi, N., & Nakagawa, M. (2023). Innovations in online classes introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic and their educational outcomes in Japan. BMC Medical Education, 23(1), e894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, T., Macinnes, S., Jarden, A., & Colla, R. (2022). The impact of a wellbeing program imbedded in university classes: The importance of valuing happiness, baseline wellbeing and practice frequency. Studies in Higher Education, 47(4), 751–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9(2), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamirinejad, S., Hojjat, K., Golzari, M., Borjali, A., & Akaberi, A. (2014). Effectiveness of resilience training versus cognitive therapy on reduction of depression in female Iranian college students. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 35(6), 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannella, L., Vahedi, Z., & Want, S. (2020). What do undergraduate students learn from participating in psychological research? Teaching of Psychology, 47(2), 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Outcomes | Pre-TTT | ANOVA | Post-Test | ANCOVA | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | |||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | F | p | η2 | M | SD | M | SD | F | p | η2 | |

| Psychological wellbeing (FS) | 41.67 | 2.09 | 40.54 | 1.76 | 0.17 | 0.68 | 0.004 | 45.06 | 1.79 | 39.44 | 1.91 | 8.02 | 0.01 | 0.17 |

| Mental wellbeing (SWEMWBS) | 21.74 | 1.07 | 19.98 | 0.67 | 2.17 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 22.29 | 1.17 | 20.25 | 0.84 | 0.35 | 0.56 | 0.009 |

| Resilience (BRS) | 3.30 | 0.17 | 3.05 | 0.14 | 1.28 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 3.48 | 0.18 | 3.09 | 0.15 | 1.40 | 0.24 | 0.03 |

| Time to Thrive had a variety of content and resources available. Which resources did you engage with? | Videos | 12 (70.6%) |

| Podcast | 10 (58.8%) | |

| Printable version or transcript | 9 (52.9%) | |

| Takeaway messages & interactive quiz | 12 (70.6%) | |

| Suggested additional resources | 4 (23.5%) | |

| Experiential exercises | 6 (35.3%) | |

| Online sessions, face-to-face workshop | 5 (29.4%) | |

| Usefulness of experiential exercises | Rating between 1 (not at all useful) and 5 (very useful) | Mdn = 4.00 |

| Mode = 4.00 | ||

| ‘I haven’t looked at any of the experiential exercises’ | 7 (39.0%) | |

| Intention of participation if no incentives were offered | Yes | 6 (33.3%) |

| No | 8 (44.4%) | |

| Considerations around timing, optional research activity versus course embedded in the curriculum, incentives facilitating commitment to engage | 4 (22.2%) | |

| Would you like the programme to be expanded and offered as a credit-bearing module for your undergraduate degree? | Yes | 14 (82.4%) |

| No | 3 (17.6%) | |

| Usefulness and enjoyability of topics | Topic 1: Stress, resilience & positive emotions | Mdn: 4.00 |

| Mode: 4.00 | ||

| Topic 2: Values, purpose & the solution-focused approach | Mdn: 4.00 | |

| Mode: 4.00 | ||

| Topic 3: Positive communication, social connectedness & loneliness | Mdn: 4.00 | |

| Mode: 4.00 | ||

| Topic 4: Impostor syndrome & overcoming procrastination | Mdn: 5.00 | |

| Mode: 5.00 | ||

| Topic 5: Eat, sleep, exercise, mindfulness & developing self-acceptance | Mdn: 4.00 | |

| Mode: 4.00 | ||

| Topic 6: Navigating transitions & developing self-growth | Mdn: 4.00 | |

| Mode: 4.00 | ||

| Programme’s impact on wellbeing | Yes | 15 (83.3%) |

| No | 2 (11.1%) | |

| Some components of TTT being impactful | 1 (5.6%) | |

| Duration of TTT | Just about right | 16 (94.1%) |

| Too long | 1 (5.9%) | |

| Overall satisfaction with TTT | Mdn: 8.00 | Mode: 6.00 |

| Would you recommend TTT to a friend? | Mdn: 7 | Mode: 7.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vourda, M.-C.; Collins, J.; Kandaswamy, R.; Bevilaqua, M.C.d.N.; Kralj, C.; Percy, Z.; Strauss, N.; Zunszain, P.A.; Dias, G.P. A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of a Wellbeing Programme Designed for Undergraduate Students: Exploring Participants’ Experiences Using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 604. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050604

Vourda M-C, Collins J, Kandaswamy R, Bevilaqua MCdN, Kralj C, Percy Z, Strauss N, Zunszain PA, Dias GP. A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of a Wellbeing Programme Designed for Undergraduate Students: Exploring Participants’ Experiences Using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(5):604. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050604

Chicago/Turabian StyleVourda, Maria-Christina, Jess Collins, Radhika Kandaswamy, Mário Cesar do Nascimento Bevilaqua, Carolina Kralj, Zephyr Percy, Naomi Strauss, Patricia A. Zunszain, and Gisele P. Dias. 2025. "A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of a Wellbeing Programme Designed for Undergraduate Students: Exploring Participants’ Experiences Using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis" Education Sciences 15, no. 5: 604. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050604

APA StyleVourda, M.-C., Collins, J., Kandaswamy, R., Bevilaqua, M. C. d. N., Kralj, C., Percy, Z., Strauss, N., Zunszain, P. A., & Dias, G. P. (2025). A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of a Wellbeing Programme Designed for Undergraduate Students: Exploring Participants’ Experiences Using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Education Sciences, 15(5), 604. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050604