Higher Education Digital Academic Leadership: Perceptions and Practices from Chinese University Leaders

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Evolution and Concepts of Digital Academic Leadership

2.2. The Reciprocal Relationship Between Digital Transformation and Academic Leadership

2.3. Multidimensional Competencies and Frameworks of DAL

2.4. Challenges in Operationalizing Digital Academic Leadership

2.5. Strategic Pathways for Effective DAL Implementation

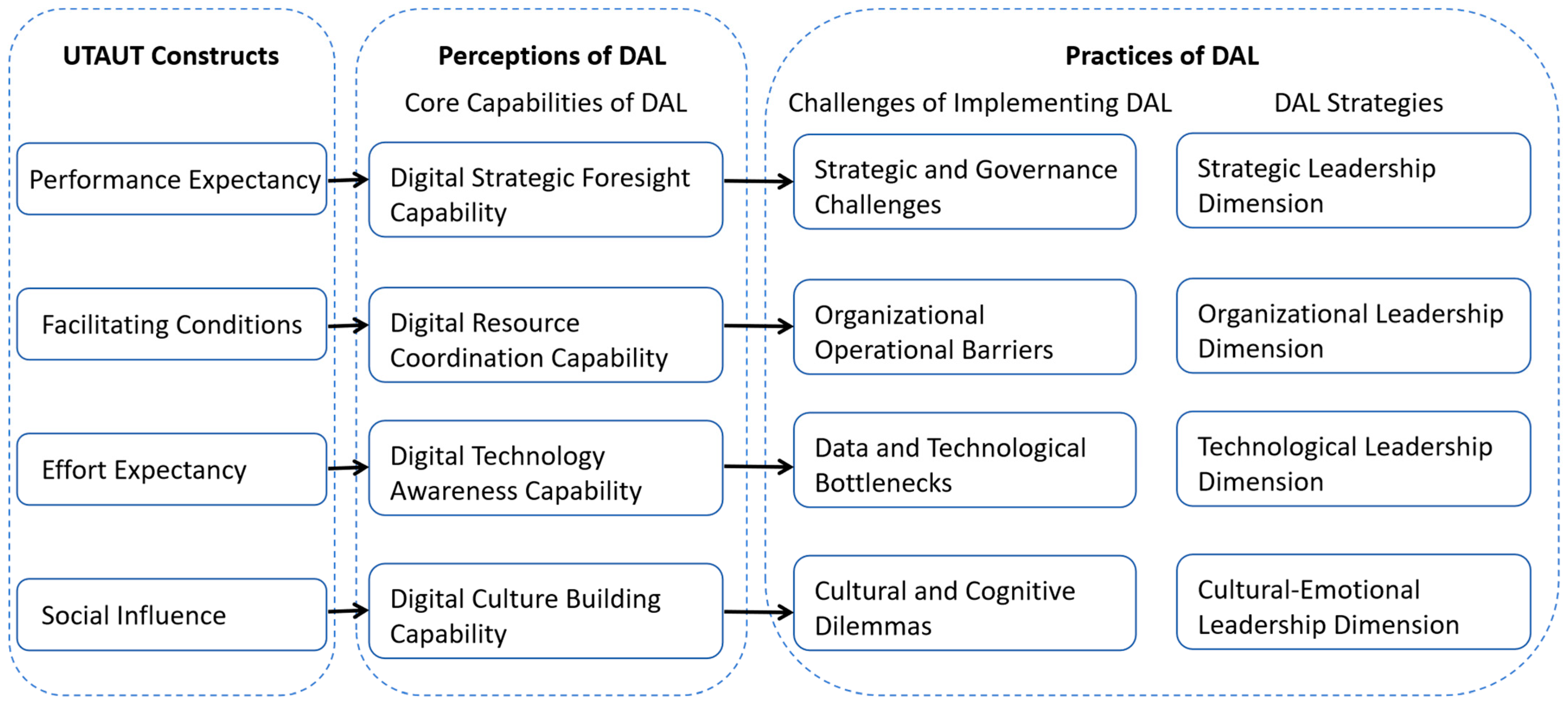

3. Analytical Framework

4. Method

4.1. Research Context

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Data Analysis

5. Findings

5.1. Empirical Results of the Questionnaire Survey

5.2. Chinese University Leaders’ Perceptions of Digital Academic Leadership

5.3. Challenges of Implementing DAL in HEIs

5.3.1. Strategic and Governance Challenges

5.3.2. Organizational Operational Barriers

5.3.3. Data and Technological Bottlenecks

5.3.4. Cultural and Cognitive Dilemmas

5.4. Strategies for HEIs Leaders to Achieve Organizational Goals Through DAL

5.4.1. Strategic Leadership Dimension

5.4.2. Organizational Leadership Dimension

5.4.3. Technological Leadership Dimension

5.4.4. Cultural-Emotional Leadership Dimension

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Have you heard of the concept of digital leadership? How do you personally understand or define it?

- In your view, what role do university administrators’ digital literacy and competencies play in advancing institutional digital transformation?

- What is your general perception of the role of digitalization in the future development of higher education institutions?

- How would you assess the current level of digitalization within your institution or department?

- What challenges have you or your team encountered in the process of institutional or departmental digital transformation? How have these challenges been addressed?

- What specific measures have you or your team implemented to integrate digital technologies into teaching, research, or administrative processes?

- How would you evaluate your own digital leadership capabilities? Through what channels or approaches do you seek to enhance your digital competencies?

- What are your thoughts on ethical and social responsibility issues related to the application of digital technologies?

- How do you perceive the level of recognition and participation in digital transformation among faculty, staff, and students at your institution?

- Are there any other important aspects of digital leadership that we have not covered but you believe deserve further exploration? For example, the use of artificial intelligence in teaching, research, or university governance.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (2020). The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2(4), 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, H., Halkiopoulos, C., Barlou, O., & Beligiannis, G. N. (2021). Transformational leadership and digital skills in higher education institutes: During the COVID-19 pandemic. Emerging Science Journal, 5(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S., & Saraih, U. N. (2024). Digital leadership in the digital era of education: Enhancing knowledge sharing and emotional intelligence. International Journal of Educational Management, 38(6), 1581–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avidov-Ungar, O., Shamir-Inbal, T., & Blau, I. (2022). Typology of digital leadership roles tasked with integrating new technologies into teaching: Insights from metaphor analysis. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(1), 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B. J., Kahai, S., & Dodge, G. E. (2000). E-leadership: Implications for theory, research, and practice. The Leadership Quarterly, 11(4), 615–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belt, E., & Lowenthal, P. (2020). Developing faculty to teach with technology: Themes from the literature. TechTrends, 64(2), 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benchea, L., & Ilie, A. G. (2023). Preparing for a New world of work: Leadership styles reconfigured in the Digital Age. European Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 15(1), 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez, J., Arenas, A., Castillo, A., & Esteves, J. (2022). Impact of digital leadership capability on innovation performance: The role of platform digitization capability. Information & Management, 59(2), 103590. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, L., & Hu, J. (2024). Digitalization leadership & innovation and changes of organization in colleges and universities on the background of digitalization transformation. Beijing Education, 46(4), 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Cartier, C. (2016). A political economy of rank: The territorial administrative hierarchy and leadership mobility in urban China. Journal of Contemporary China, 25(100), 529–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cegielski, O. M. (2023). Making sense of technological change in the Post-COVID Era: Digital leadership and equitable learning opportunities in Colorado’s PK-12 schools. University of Colorado Colorado Springs. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W., & Zhang, J. H. (2023). Does shared leadership always work? A state-of-the-art review and future prospects. Journal of Work-Applied Management, 15(1), 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z., Khuyen, D. N. B., Caliskan, A., & Zhu, C. (2024). A systematic review of digital academic leadership in higher education. International Journal of Higher Education, 13(4), 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z., & Zhu, C. (2021). Academic members’ perceptions of educational leadership and perceived need for leadership capacity building in Chinese higher education institutions. Chinese Education & Society, 54(5–6), 171–189. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z., & Zhu, C. (2024). Educational leadership styles and practices perceived by academics: An exploratory study of selected Chinese universities. Educational Management Administration & Leadership. 17411432241294171. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/17411432241294171 (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Chugh, R., Turnbull, D., Cowling, M. A., Vanderburg, R., & Vanderburg, M. A. (2023). Implementing educational technology in Higher Education Institutions: A review of technologies, stakeholder perceptions, frameworks and metrics. Education and Information Technologies, 28(12), 16403–16429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwen-Li, C., Arisanti, I., Octoyuda, E., & Insan, I. (2022). E-leadership analysis during pandemic outbreak to enhanced learning in higher education. TEM Journal, 11(2), 932–938. [Google Scholar]

- Cortellazzo, L., Bruni, E., & Zampieri, R. (2019). The role of leadership in a digitalized world: A review. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z. (2023). Analysis of China’s higher education digitalization strategies. Bulletin of the LN Gumilyov Eurasian National University. Political Science. Regional Studies. Oriental Studies. Turkology Series, 143(2), 201–210. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, H. A. (2017). Cultivating social capital in undergraduate research: Key sources and distinctions by gender. The University of Texas at El Paso. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Technology acceptance model: TAM. Al-Suqri, MN, Al-Aufi, AS: Information Seeking Behavior and Technology Adoption, 205(219), 5. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y. (2024). Transformation of bureaucracy in digital times. In Emerging developments and technologies in digital government (pp. 131–140). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N. K. (2017). The research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dima, A. M., Point, S., Maassen, M. A., & Jansen, A. (2021). Academic leadership: Agility in the digital revolution. Proceedings of the International Conference on Business Excellence, 15(1), 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, K. (2020). Dimension Characteristics and Promotion Path of Leadership in Digital Age. Leadership Science, 46(16), 60–62. [Google Scholar]

- Eberl, J. K., & Drews, P. (2021). Digital leadership-mountain or molehill? A literature review. In Innovation through information systems: Volume III: A collection of latest research on management issues (pp. 223–237). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers, U. D. (2020). Digital leadership in higher education. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Leadership Studies, 1(3), 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhan, T., Uzunbacak, H. H., & Aydin, E. (2022). From conventional to digital leadership: Exploring digitalization of leadership and innovative work behavior. Management Research Review, 45(11), 1524–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y. (2019). Digital leadership. Orient Publishing Center. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, D. (2020). Understanding China’s school leadership: Interpreting the terminology (p. 278). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Ghamrawi, N., & Tamim, R. M. (2023). A typology for digital leadership in higher education: The case of a large-scale mobile technology initiative (using tablets). Education and Information Technologies, 28(6), 7089–7110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granić, A. (2022). Educational technology adoption: A systematic review. Education and Information Technologies, 27(7), 9725–9744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P. (2018). Bringing context out of the shadows of leadership. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 46(1), 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, A., Jones, M., & Ismail, N. (2022). Distributed leadership: Taking a retrospective and contemporary view of the evidence base. School Leadership & Management, 42(5), 438–456. [Google Scholar]

- Hebert, D. M., & Lovett, M. (2021). Elements for academic leadership in a virtual space. Journal of Higher Education Policy And Leadership Studies, 2(3), 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderikx, M., & Stoffers, J. (2022). An exploratory literature study into digital transformation and leadership: Toward future-proof middle managers. Sustainability, 14(2), 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, J. E., & Kozlowski, S. W. (2014). Leading virtual teams: Hierarchical leadership, structural supports, and shared team leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(3), 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, M. C., & Gutworth, M. B. (2020). A meta-analysis of virtual reality training programs for social skill development. Computers & Education, 144, 103707. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L., Jiang, N., Huang, H., & Liu, Y. (2022). Perceived competence overrides gender bias: Gender roles, affective trust and leader effectiveness. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 43(5), 719–733. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X. (2018). Social media use by college students and teachers: An application of UTAUT2 [Doctoral dissertation, Walden University]. [Google Scholar]

- Jameson, J., Rumyantseva, N., Cai, M., Markowski, M., Essex, R., & McNay, I. (2022). A systematic review and framework for digital leadership research maturity in higher education. Computers and Education Open, 3, 100115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H. F. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika, 39(1), 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakose, T., Polat, H., & Papadakis, S. (2021). Examining teachers’ perspectives on school principals’ digital leadership roles and technology capabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability, 13(23), 13448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasmia, N. B., & M’hamed, H. (2023). Digitalization of higher education: Impacts on management practices and institutional developement. A literature review. Conhecimento & Diversidade, 15(39), 56–82. [Google Scholar]

- Kawiana, I. G. P. (2023). Digital leadership: Building adaptive organizations in the digital age. Jurnal Multidisiplin Sahombu, 3(01), 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya-Capocci, S., O’Leary, M., & Costello, E. (2022). Towards a framework to support the implementation of digital formative assessment in higher education. Education Sciences, 12(11), 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khemtong, N., Promchom, K., Thumsen, P., & Wechayalak, N. (2024). Digital leadership relationships among school administrators with the effectiveness of academic work in the new normal era. Higher Education Studies, 14(3), 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, H. J. (2020). Investigating older adults’ decisions to use mobile devices for learning, based on the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. Interactive Learning Environments, 28(7), 890–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakemond, N., Holmberg, G., & Pettersson, A. (2021). Digital transformation in complex systems. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 71, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C. (2017). Leadership in virtual teams: A multilevel perspective. Human Resource Management Review, 27(4), 648–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. P., Chiu, C. K., & Liu, N. T. (2019). Developing virtual team performance: An integrated perspective of social exchange and social cognitive theories. Review of managerial science, 13, 671–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A. (2011). Unraveling the myth of meritocracy within the context of US higher education. Higher education, 62, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Dai, Q., & Chen, J. (2024). Factors affecting teachers’ use of digital resources for teaching mathematical cultures: An extended UTAUT-2 model. Education and Information Technologies, 30, 7659–7688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., Zha, S., & He, W. (2019). Digital transformation challenges: A case study regarding the MOOC development and operations at higher education institutions in China. TechTrends, 63, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, B. (2013). Intellectual leadership in higher education: Renewing the role of the university professor. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Marikyan, M., & Papagiannidis, P. (2021). Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. TheoryHub book. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, X., Dawod, A. Y., & Phaphuangwittayakul, A. (2023, February 4–5). The implications, challenges, and pathways of digital transformation of University Education in China. 7th TICC International Conference, Chiang Mai, Thailand. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Msila, V. (2022). Higher education leadership in a time of digital technologies: A south african case study. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 12(10), 1110–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noureddine, R., Boote, D., & Campbell, L. O. (2025). Assessing the validity of utaut among higher education instructors: A meta-analysis. Education and Information Technologies, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. C. (1978). An overview of psychological measurement. In Clinical diagnosis of mental disorders: A handbook (pp. 97–146). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Oberer, B., & Erkollar, A. (2018). Leadership 4.0: Digital leaders in the age of industry 4.0. International journal of organizational leadership, 7(4), 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, P., Martin, P. Y., Carvalho, T., Hagan, C. O., Veronesi, L., Mich, O., Saglamer, G., Tan, M. G., & Caglayan, H. (2019). Leadership practices by senior position holders in Higher Educational Research Institutes: Stealth power in action? Leadership, 15(6), 722–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasolong, H., & Setini, S. (2021). Digital leadership in facing challenges in the era industrial revolution 4.0. Webology, 1, 975–990. [Google Scholar]

- Philippart, M. H. (2021). Success factors to deliver organizational digital transformation: A framework for transformation leadership. Journal of Global Information Management (JGIM), 30(8), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porfírio, J. A., Carrilho, T., Felício, J. A., & Jardim, J. (2021). Leadership characteristics and digital transformation. Journal of Business Research, 124, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, N., Kiani, S., & Tavakoli, R. (2024). Organizational alignment in cross-functional digital transformation initiatives. Digital Transformation and Administration Innovation, 2(3), 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ratajczak, S. (2022). Digital leadership at universities–a systematic literature review. In Forum scientiae oeconomia (Vol. 10, No. 4, pp. 133–150). Wydawnictwo Naukowe Akademii WSB. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E. M., Singhal, A., & Quinlan, M. M. (2014). Diffusion of innovations. In An integrated approach to communication theory and research (pp. 432–448). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E. M., & Smith, L. (1962). Bibliography on the diffusion of innovations. Department of Communication, Michigan State University. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, J., Cai, Y., & Stensaker, B. (2024). University managers or institutional leaders? An exploration of top-level leadership in Chinese universities. Higher Education, 87(3), 703–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainger, G. (2018). Leadership in digital age: A study on the role of leader in this era of digital transformation. International Journal on Leadership, 6(1), 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sanati, S. R., Jannatipour, M., Jamshidi, R., Rohani, M. H., & Sadeghi, M. E. (2024). Developing a culturally-aligned digital transformation framework for iranian organizations: “greentech digital transformation (gdt) framework”. International Journal of Innovation in Management, Economics and Social Sciences, 4(4), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, R., & Teo, T. (2019). Unpacking teachers’ intentions to integrate technology: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 27, 90–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, T. P., & Barbuto, J. E., Jr. (2013). A multilevel framework: Expanding and bridging micro and macro levels of positive behavior with leadership. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 20(3), 274–286. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, L. (2023). An exploration of digital leadership enhancement strategies for higher education leaders. Huazhang, (04), 123–125. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, W., Huang, Y., & Fan, W. (2020). Morality and ability: Institutional leaders’ perceptions of ideal leadership in Chinese research universities. Studies in Higher Education, 45(10), 2092–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tana, S., Breidbach, C. F., & Burton-Jones, A. (2023). Digital transformation as collective social action. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 24(6), 1618–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wart, M., Roman, A., Wang, X., & Liu, C. (2019). Operationalizing the definition of e-leadership: Identifying the elements of e-leadership. International review of administrative sciences, 85(1), 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y., & Xu, X. (2012). Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quarterly, 36(1), 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B., Liu, Y., & Parker, S. K. (2020). How does the use of information communication technology affect individuals? A work design perspective. Academy of Management Annals, 14(2), 695–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. (2021). Developing a nuanced understanding of the factors that influence digital inclusion for active and healthy ageing among older people [Doctoral dissertation, University of Sheffield]. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, K. S., & Wäger, M. (2019). Building dynamic capabilities for digital transformation: An ongoing process of strategic renewal. Long range planning, 52(3), 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weritz, P. (2021). Understanding is leadership in the new normal: A systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the 27th Americas Conference on Information Systems (AMCIS 2021). Association for Information Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, J., Wang, M., & Zhang, S. (2023). School culture and teacher job satisfaction in early childhood education in China: The mediating role of teaching autonomy. Asia Pacific Education Review, 24(1), 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J. (2019). Digital transformation in higher education: Critiquing the five-year development plans (2016–2020) of 75 Chinese universities. Distance Education, 40(4), 515–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S., Chen, P., & Zhang, G. (2024). Exploring chinese university educators’ acceptance and intention to use AI tools: An application of the UTAUT2 model. SAGE Open, 14(4), 21582440241290013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L., Rashid, A. M., & Ouyang, S. (2024). The unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) in higher education: A systematic review. Sage Open, 14(1), 21582440241229570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S., & Yang, Y. (2021). Education informatization 2.0 in China: Motivation, framework, and vision. ECNU Review of Education, 4(2), 410–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R. (2016). Cultural challenges facing East Asian higher education: A preliminary assessment. In The palgrave handbook of Asia pacific higher education (pp. 227–245). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X., Gou, R., & Xie, Y. (2023). Principals’ data leadership: A key capability for implementing the national education digital strategy. China Educational Technology, 44(5), 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, L., & Jiang, X. (2023). The value orientation and path choice of digital leadership cultivation for leaders in colleges and universities. Henan Education, 19(1), 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y., Zhao, R., & Yu, X. (2022). Enhancing virtual team performance via high-quality interpersonal relationships: Effects of authentic leadership. International Journal of Manpower, 43(4), 982–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., & Zheng, X. (2023). Digital Leadership: Structural Dimensions and Scale Development. Business and Management Journal, 45(11), 152–168. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C., & Caliskan, A. (2021). Educational leadership in Chinese higher education. Chinese Education & Society, 54(5–6), 161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Zupancic, T., Herneoja, A., Schoonjans, Y., & Achten, H. (2018). A research framework of digital leadership. Computing for a Better Tomorrow, 2, 641–646. [Google Scholar]

| Proposed Dimensions/Key Competencies | Specific Dimensional Indicators | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Three Proposed Dimensions/Key Competencies | Vision for technological integration; resource management; fostering collaboration | Msila (2022) |

| Strategic planning capability; organizational mobilization capability; digital infrastructure (resource-, literacy-, institutional-based) | Cai and Hu (2024) | |

| Trust-building; collaborative team dynamics; adaptive communication | Hebert and Lovett (2021) | |

| Forward-thinking; data literacy; value recognition | Fang (2019) | |

| Four Proposed Dimensions/Key Competencies | mindful change capability; professional and operational expertise; environmental sensing capability; interactive resonance competence | Duan (2020) |

| Data literacy; digital tool proficiency; ethical decision-making in AI; fostering digital citizenship | Jameson et al. (2022) | |

| Five Proposed Dimensions/Key Competencies | Digital awareness; technology vision; technology adoption; collaborative practices; challenge addressing | Cheng et al. (2024) |

| 5D Typology: Digital competence; digital culture; digital differentiation; digital governance; digital advocacy | Ghamrawi and Tamim (2023) | |

| Digital leadership; charisma; foresight; influence; decision-making; control | Shan (2023) |

| Theory | Core Constructs | Primary Focus | Theoretical Basis | Moderators | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) |

| Predicting general human behavior | Extension of theory of reasoned action (TRA) | / | Ajzen (1991, 2020) |

| Diffusion of Innovations (DOI) |

| Adoption dynamics in social systems | Communication Theory | Social system norms and communication channels | Rogers and Smith (1962); Rogers et al. (2014) |

| Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) |

| Technology adoption in organizational settings | Rooted in TRA and TPB | / | Davis (1989) |

| Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) |

| Organizational technology adoption | Integrates TAM, TPB, DOI, and other models | Age, gender, experience and voluntariness | Venkatesh et al. (2003) |

| UTAUT2 | UTAUT constructs +

| Consumer technology adoption | Evolutionary extension of UTAUT | Age, gender, and experience (expanded) | Venkatesh et al. (2012) |

| Construct | Operational Definition | Example in HE | Theoretical Foundations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Expectancy | The degree to which using a technology will provide benefits in achieving specific job performance | Perceived effectiveness of digital tools in enhancing institutional decision-making | TAM (Perceived Usefulness) |

| Effort Expectancy | The perceived ease of use associated with technology adoption | Learning curve required to implement AI-driven academic monitoring systems | TAM (Perceived Ease of Use) |

| Social Influence | The extent to which users perceive that significant referent groups endorse technology adoption | Peer universities’ successful digital transformation impacts adoption willingness | DOI (Social System Norms) |

| Facilitating Conditions | Available organizational resources and technical infrastructures enabling technology implementation | Government funding for smart campus initiatives | TPB (Perceived Behavioral Control) |

| Participant | Gender | School Type | School Location | Administrative Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDDF1 | Male | Double First-Class University | Guangdong Province | Dean, School of Automation |

| ZJPK2 | Male | Provincial Key University | Zhejiang Province | Director, Campus Construction and Management Department |

| ZJHV3 | Male | Higher Vocational College | Zhejiang Province | Director, Organization Department (Talent Office) |

| GDHV4 | Male | Higher Vocational College | Guangdong Province | Director, Faculty Development Center |

| GDPK5 | Male | Provincial Key University | Guangdong Province | Party Secretary, School of Data Science and Artificial Intelligence |

| ZJDF6 | Male | Double First-Class University | Zhejiang Province | Director, Yangtze River Delta Smart Oasis Innovation Center |

| GDHV7 | Male | Higher Vocational College | Guangdong Province | Head, Student Affairs Office, School of General Education |

| Variable | Category | n | % | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 48 | 62% | 1.38 | 0.49 |

| Female | 30 | 39% | |||

| Institution Type | Double First-Class | 4 | 5% | 2.55 | 0.60 |

| Provincial Key | 27 | 35% | |||

| Higher Vocational College | 47 | 60% | |||

| Tenure in Position | Below 5 years | 48 | 62% | 1.71 | 0.49 |

| 5–10 years | 17 | 22% | |||

| 10–15 years | 4 | 5% | |||

| Over 15 years | 9 | 12% | |||

| Disciplinary Cluster | Natural–Applied Sciences (NASs) | 23 | 30% | / | / |

| Humanities–Social Sciences (HSSs) | 41 | 52% | |||

| Interdisciplinary–Hybrid Fields (IHFs) | 14 | 18% | |||

| Total | 78 | 100% |

| Competency Domain | Male (n = 48) M(SD) | Female (n = 30) M(SD) | t(df), p | Undergraduate University (n = 31) M(SD) | Higher Vocational College (n = 47) M(SD) | t(df), p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Strategic Change | 4.12 (0.72) | 4.17 (0.61) | −0.33(76), 0.742 | 3.98 (0.69) | 4.25 (0.66) | −1.72(76), 0.090 |

| Digital Resource Building | 3.67 (0.96) | 3.23 (0.83) | 2.07(76), 0.042 * | 3.29 (0.88) | 3.65 (0.95) | −1.67(76), 0.100 |

| Digital Ethical Empathy | 4.16 (0.74) | 4.22 (0.60) | −0.34(76), 0.733 | 3.98 (0.76) | 4.31 (0.61) | −2.12(76), 0.037 * |

| Digital Cognitive Practice | 4.05 (0.74) | 3.72 (0.56) | 2.07(76), 0.042 * | 3.78 (0.72) | 4.02 (0.66) | −1.50(76), 0.138 |

| Competency Domain | NASs M(SD) | HSSs M(SD) | IHFs M(SD) | F(2,75) | p | Post Hoc Comparisons (t, p, Cohen’s d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Strategic Change | 4.26 (0.53) | 4.01 (0.79) | 4.33 (0.46) | 1.695 | 0.191 | NASs-IHFs: t = −0.40, p = 0.695, d = −0.13 NASs-HSSs: t = 1.36, p = 0.178, d = 0.34 HSSs-IHFs: t = −1.43, p = 0.160, d = −0.50 |

| Digital Resource Building | 3.65 (0.88) | 3.35 (0.93) | 3.71 (0.99) | 1.217 | 0.302 | NASs-IHFs: t = −0.19, p = 0.843, d = −0.06 NASs-HSSs: t = 1.27, p = 0.210, d = 0.32 HSSs-IHFs: t = −1.24, p = 0.220, d = −0.35 |

| Digital Ethical Empathy | 4.20 (0.59) | 4.17 (0.79) | 4.20 (0.53) | 0.013 | 0.987 | NASs-IHFs: t = −0.00, p = 0.997, d = −0.00 NASs-HSSs: t = 0.13, p = 0.896, d = 0.04 HSSs-IHFs: t = −0.11, p = 0.911, d = −0.05 |

| Digital Cognitive Practice | 4.12 (0.57) | 3.78 (0.77) | 4.02 (0.57) | 2.088 | 0.131 | NASs-IHFs: t = 0.51, p = 0.611, d = 0.17 NASs-HSSs: t = 1.89, p = 0.063, d = 0.48 HSSs-IHFs: t = −1.11, p = 0.274, d = −0.34 |

| Dimensions | Core Capabilities | Definitions |

|---|---|---|

| Strategic Dimension | Digital Strategic Foresight Capability | To anticipate emerging digital trends and formulate long-term strategies that align with institutional goals |

| Organizational Dimension | Digital Resource Coordination Capability | Effective integration and management of digital assets across various organizational units |

| Technological Dimension | Digital Technology Awareness Capability | A comprehensive understanding of current and emerging digital technologies and their potential applications |

| Cultural Dimension | Digital Culture Building Capability | Cultivating an organizational culture that embraces digital innovation and continuous learning |

| Categories | Subcategories | Themes | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Challenges of Implementing DAL in HEIs | Strategic and Governance Challenges | Lack of digital regulatory and ethic framework | Medium |

| High investment costs and limited funding in digitalization | High | ||

| Organizational Operational Barriers | Structural rigidity and cross-departmental collaboration failure | Medium | |

| Lack of professional teams and expertise | High | ||

| Data and Technological Bottlenecks | Data governance failures, information silos, and real-time update delays | Medium | |

| Data accuracy and algorithmic ethical risks | Low | ||

| Cultural and Cognitive Dilemmas | Faculty technostress, digital literacy divide, and institutional training gaps | High | |

| Dynamic tension between technological rationality and pedagogical humanism | Low | ||

| Strategies for HEIs Leaders to Achieve Organizational Goals through DAL | Strategic Leadership Dimension | Institutionalizing national policy-embedded innovation | Medium |

| Coordinating cross-departmental synergies | Medium | ||

| Organizational Leadership Dimension | Orchestrating hybrid talent deployment | High | |

| Optimizing adaptive governance and resource allocation | Medium | ||

| Technological Leadership Dimension | Hardware: architecting intelligent campus infrastructures | High | |

| Software: re-engineering integrated digital ecosystem | High | ||

| Cultural–Emotional Leadership Dimension | Cultivating techno-cultural ambidexterity | Low | |

| Mediating technophobia through role modeling and structural support | Medium |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jing, M.; Guo, Z.; Wu, X.; Yang, Z.; Wang, X. Higher Education Digital Academic Leadership: Perceptions and Practices from Chinese University Leaders. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 606. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050606

Jing M, Guo Z, Wu X, Yang Z, Wang X. Higher Education Digital Academic Leadership: Perceptions and Practices from Chinese University Leaders. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(5):606. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050606

Chicago/Turabian StyleJing, Meiying, Zhen Guo, Xiao Wu, Zhi Yang, and Xiaqing Wang. 2025. "Higher Education Digital Academic Leadership: Perceptions and Practices from Chinese University Leaders" Education Sciences 15, no. 5: 606. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050606

APA StyleJing, M., Guo, Z., Wu, X., Yang, Z., & Wang, X. (2025). Higher Education Digital Academic Leadership: Perceptions and Practices from Chinese University Leaders. Education Sciences, 15(5), 606. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050606