Abstract

This survey study aims to understand how college students use and perceive artificial intelligence (AI) tools in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). It reports students’ use, perceived motivations, and ethical concerns and how these variables are interrelated. Responses (n = 822) were collected from seven universities in five UAE emirates. The findings show widespread use of AI tools (79.6%), with various factors affecting students’ perceptions about AI tools. Students also raised concerns about the lack of guidance on using AI tools. Furthermore, mediation analyses revealed the underlining psychological mechanisms pertaining to AI tool adoption: perceived benefits fully mediated the relationship between AI knowledge and usefulness perceptions, peer pressure mediated the relationship between academic stress and AI adoption intent, and ethical concerns fully mediated the relationship between ethical perceptions and support for institutional AI regulations. The findings of this study provide implications for the opportunities and challenges posed by AI tools in higher education. This study is one of the first to provide empirical insights into UAE college students’ use of AI tools, examining mediation models to explore the complexity of their motivations, ethical concerns, and institutional guidance. Ultimately, this study offers empirical data to higher education institutions and policymakers on student perspectives of AI tools in the UAE.

1. Introduction

Diffusion of Innovation Theory (DIT, Rogers, 1962) addresses how innovations, such as AI tools, spread within a social system, emphasizing the role of communication channels, social influence, and the perceived attributes of the innovation. DIT explains six factors for a new technology to spread in society. One of the key factors in DIT is relative advantage or the degree to which a technological innovation is seen as better than the existing technology. Further, according to DIT, in order for a technological innovation to spread in the whole society, it has to be used by a “critical mass” or at least 10% of the population in a given society (Rogers, 1962). AI technologies have affected many areas in our society in a short period of time (Polak & Anshari, 2024). In the context of higher education, the use of AI tools seems to have already reached beyond the critical mass for college students (Farhi et al., 2023). AI tools have been shown to have the capacity to assist with self-learning and group-work for student learning, as well as provide feedback to students (Biggs et al., 2022). Higher education is considered to be a hub for creating and disseminating knowledge, and AI-related technologies are transforming how higher education fulfils its functions. For example, research has shown that AI tools offer new ways to engage students with their academic tasks and perform more effectively in achieving academic goals (e.g., Abbas et al., 2024; Johnston et al., 2024). Undoubtedly, modern technologies such as AI tools have to be incorporated into teaching to promote effective learning higher education (Alenezi, 2021). Therefore, the key issue here is to understand how college students currently use and perceive these technologies.

AI tools offer students many advantages, including assisting with task efficiency, checking grammar, improving the flow of writing, and suggesting creative ideas (Chen et al., 2020). AI tools are now able to provide data analysis with interpretation functions (Santosh, 2020). Despite the advantages, the use of AI in higher education poses challenges. There are fears regarding academic misconduct through AI. For example, a major issue is plagiarism, and professors worry about students’ misuse of AI tools, challenging academic integrity (Biggs et al., 2022). The ability of AI to generate essays, summarize documents, and code has led universities to reconsider plagiarism detection and assessment strategies. Furthermore, ethical issues pertaining to data security and data processing inadequacies have not been properly addressed. There is also growing concern among students that AI tools collect their information without notice, which could possibly be misused or even abused (A. Nguyen et al., 2023). Another important issue is the vague nature of the policies about the ethical issues of using AI in academia. Research suggests that many students do not know about institutional AI policies, and, accordingly, confusion exists about the extent to which AI tools are allowed to be used (A. Nguyen et al., 2023). For example, while some institutions strictly regulate the use of AI tools for students’ work, others encourage responsible use without providing specific guidelines that students can clearly and confidently adhere to. Such ambiguity may lead to ethical dilemmas, and students may spend time trying to figure out whether their specific use violates the university guidelines. Therefore, clear and transparent academic integrity guidelines at the institutional level are warranted to address ethical challenges while ensuring effective and confident use of AI tools.

The UAE constitutes a unique case of AI being adopted within higher education and cultural contexts. The UAE has rapidly embraced technology as part of its national innovation agenda, with AI playing a central role in its vision for economic and educational transformation. The UAE is one of the few countries that has a Ministry of Artificial Intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Office, n.d.). With its diverse and multicultural population, higher education institutions in the UAE also place a strong emphasis on integrating advanced technologies into learning environments (Fernandez et al., 2022). Such environments shape college students’ perceptions and adoption of AI tools (Artificial Intelligence Office, n.d.) and make the UAE a unique case for exploring how AI tool usage influences higher education.

While prior research has explored the use and perceptions of AI tools among college students (e.g., Farhi et al., 2023; Huang, 2024; Ravšelj et al., 2025), few studies have comprehensively examined the variables that influence students’ use of AI tools in the UAE higher education context. This study addresses this gap by investigating how students use AI tools and by identifying the variables that influence student perceptions of AI tools. Through this approach, the study examines the relationships between the key variables to offer deeper insights into the AI adoption mechanisms in higher education context in UAE.

The main purpose of this study is to examine the use of and perceptions on AI tools among college students in UAE higher education institutions. More specifically, the research questions guiding this study are the following: (1) What factors influence the adoption of AI tools among college students in UAE higher education institutions? (2) How do these factors relate to students’ perceptions of the usefulness and impact of AI tools on their learning experiences? (3) What are the perceptions of college students in the UAE regarding the ethical issues and policies related to AI tool usage in their academic environment?

This study will add knowledge to the body of research on AI in higher education settings and provide insights for higher education institutions and policymakers in developing guidelines for students using AI tools.

2. Literature Review

AI is defined as a system created to think, act, and analyze, in a rational manner, similar to humans. AI tools can perform tasks, solve problems, and analyze and perceive information (Biggs et al., 2022). Educational institutions have traditionally been the main center for knowledge and dissemination, but with the easier access to knowledge and information in our time (Alenezi, 2021), these institutions are no longer the sole gatekeepers for information. Instead, they have adopted contemporary technologies in their practice to achieve the mission of education, support student development, and provide important and diverse educational services (Alenezi, 2021).

College students are using AI tools to enhance their learning experience and customize content that meets their needs, as these tools have become time and effort saving, and they improve engagement (Abbas et al., 2024). On the other hand, although AI tools demonstrate great capabilities that are similar to those of humans, their policies should be compatible with educational goals, especially in adhering to ethical standards to ensure their proper use (Acosta-Enriquez et al., 2024; Alenezi, 2021). As AI tool adoption continues to grow, concerns about the use of AI tools have increased, and higher education institutions currently face great challenges in digital transformation (Abbas et al., 2024; Alenezi, 2021). These drivers of digital transformation have become essential, requiring policies that support responsible AI use among students while allowing colleges and professors to prioritize the development of new skills that enhance students’ capabilities and adapt to evolving technologies (Reiss, 2021).

3. College Students’ Use of AI Tools

The presence of AI tools in higher education is important in learning new methods that help enhance student engagement (Santosh, 2020). AI tools help simplify administrative processes and enhance the quality of education through participation in student activities (Johnston et al., 2024). The use of AI tools by students for academic or professional purposes has become widespread at the present time, as students believe that universities should help them develop their skills in using these tools for their future careers (Johnston et al., 2024). Studies have shown that students feel confident and independent in learning through their use of AI-powered writing programs (Rodzi et al., 2023). For example, while ChatGPT is one of the most widely recognized AI writing tools, other AI-powered writing programs such as QuillBot, Writesonic, and Grammarly are also frequently used in helping students with writing tasks (Marzuki et al., 2023).

The technology acceptance model (TAM; Davis, 1989) suggests that users accept new technologies when they perceive their usefulness and if technologies are easy to use. In the context of AI tools in higher education, perceived usefulness refers to students’ belief that AI enhances their academic performance, such as improving writing quality, automating tasks, or providing personalized learning support (Davis, 1989; Ibrahim et al., 2025). Perceived ease of use reflects how effortless students find AI tools to use, which influences their intention to integrate AI tools into daily academic tasks (Ibrahim et al., 2025). Research indicates that more than half of higher education students perceive AI tools as useful (Benuyenah & Dewnarain, 2024; Johnston et al., 2024). The use of these tools for students helps improve results, in addition to providing support and saving time and effort, thus increasing productivity (Köchling & Wehner, 2023). Many studies have found that AI tools often provide accurate support and facilitate the completion of many academic tasks, which enhances students’ learning processes. For example, the AI tool ChatGPT is one of the tools known among students, as it significantly helps in adaptive learning and writing, in addition to explaining complex concepts (Johnston et al., 2024). On the other hand, the excessive use of these tools causes problems with academic integrity and often provides false information, and fears of total reliance on these tools thus reduces creativity and thinking among students (Biggs et al., 2022).

4. Types of AI Tools in Higher Education

Nowadays, there is a broad variety of AI tools in higher education institutions, as these tools are designed for various purposes and for different medical, mathematical, and human fields. For example, there are smart education technologies that analyze and extract data, such as measurement and statistical data, and these tools focus on educational content management systems and test results (Chen et al., 2020). Another AI tool that is important in higher education institutions is chatbots, as studies have shown that AI-generated chatbots are widely used in higher education institutions, with chatbots acting as virtual teachers and helping to answer many inquiries and provide academic support to students (McGrath et al., 2024). Intelligent chatbots provide advantages to teachers, as chatbots help reduce the burden, for example, by providing support outside of working hours and handling inquiries, in addition to enhancing student participation and providing interactive educational experiences and creating a more interactive environment (Alenezi, 2021; McGrath et al., 2024).

AI tools have powerful capabilities, as they allow students to interact more effectively with their study materials, enabling personalized learning, simplifying the study processes, and fostering educational environments that meet the individual progress of students (Chen et al., 2020). For example, the “MATHia” tool from Carnegie Learning provides personalized mathematics education like one-on-one tutoring, while the Century Tech tool works to enhance students’ personalized education through interactive learning and analysis of student behaviors (Chen et al., 2020). AI tools such as “Knewton” coordinates and modifies content to suit students’ progress by evaluating their content (Shi et al., 2024). Grammarly provides immediate modifications and writing improvement through spelling rules, writing styles, and the development of creative writing, which helps students develop writing skills and positively affects their academic performance (Abubakari, 2024).

Perceived Benefits of AI Tools for College Students

Access to AI tools has allowed students to choose each tool separately to complete tasks, which suits different learning styles and students’ goals. The perceived benefits of AI tools in higher education institutions are many, which have enhanced students’ educational experiences and academic performance, as these tools help improve writing skills and productivity, provide personalized feedback to students, and enhance students’ creative thinking (Köchling & Wehner, 2023). These benefits have often made the educational environment more attractive to students by increasing productivity, increasing learning outcomes and self-confidence, supporting knowledge discovery, and developing personal educational skills. Research shows that students report improved motivation and engagement when using AI tools, which can lead to better academic performance (Benuyenah & Dewnarain, 2024; Yurt & Kasarci, 2024).

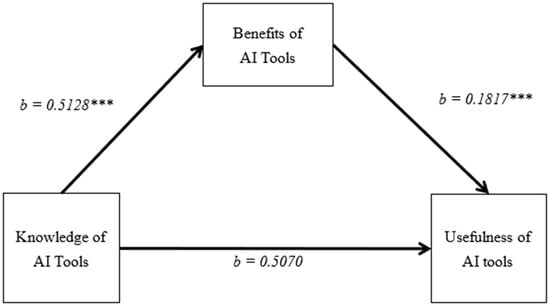

Individuals’ knowledge of AI tools is important in determining whether the adoption and usage of the tool for academic purposes would be effective. For example, studies have indicated that knowledge is the major determinant of attitude about and perception of technology (Davis, 1989; Venkatesh et al., 2003). However, knowledge about AI tools alone does not necessarily result in perceptions of their usefulness. For instance, knowledge of technologies such as functionality or features may lead users to perceive the benefits of the use of technology. Without realizing benefits like increased work quality, efficiency in terms of time saving, or enhanced decision making, knowledge about the technology itself is less likely to lead to perceptions of its usefulness. That is, the general benefits derived from technologies can act as a mediator leading to the perception of usefulness. Past research on the use of technologies suggests that knowledge about the automation of tasks or data-driven insights is more likely to lead to users perceiving the technologies as useful in their professional or personal contexts, hence perceiving them as beneficial (Gefen & Straub, 2000). This mediational model is consistent with the TAM (Davis, 1989), which posits that perceived usefulness is a prime determinant of technology adoption, influenced by antecedents such as knowledge and perceived benefits (Venkatesh et al., 2003). Figure 5 illustrates the role of the mediator and the benefits of AI tools. Thus, we propose that the relationship between knowledge of AI tools and perceived usefulness will be mediated by perceived benefits. Hence,

H1:

The relationship between students’ perceived knowledge about AI tools and perceived usefulness of AI tools will be mediated by perceived benefits of AI tools.

5. Intention to Use AI Tools

Students can be motivated to use AI tools because of various factors. Various tasks in college often put students under study pressure due to meeting deadlines, achieving higher grades, exams, and other academic tasks (Abbas et al., 2024). Students in such situations can try to reduce their stress by finding more efficient or easy ways to handle their stress. Knowing the effectiveness and convenience of AI tools in handling their tasks can lead to more intention of using AI tools. Thus, study pressure may create the need for students to seek solutions to improve academic efficiency, making AI tools a solution for students.

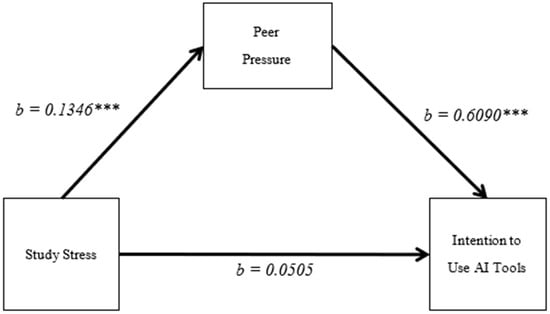

However, the presence of study pressure does not necessarily mean students will adopt technologies, as they may have other potential solutions. There may be other variables that may mediate the relationship between study stress and the intention to use AI tools. One of such variables can be peer pressure. Peer pressure acts as a social influence mechanism by encouraging behaviors such as accepting or rejecting a certain idea based on the perceptions of other individuals around (Changalima et al., 2024). When students observe their peers using AI tools to help with academic tasks, they are more likely to adopt these tools in order to enhance their own academic performance. Peer pressure can encourage both ethical and unethical AI use, depending on the prevailing academic culture and social norms. However, one worrisome situation is that, under the stress of deadlines or obtaining higher grades, students may feel pressured to use AI tools, submitting AI-generated work without proper attribution or without contemplating the ethical consequences (H. M. Nguyen & Goto, 2024). When unethical AI use is perceived to be acceptable within peer groups, students can be more likely to rationalize their misconduct. Conversely, peer influence can also promote ethical AI use by encouraging responsible engagement, such as using AI for learning support or collaborative work with proper institutional guidance.

Understanding the role of peer pressure is especially important in countries such as the UAE where solidarity among college students is strong and often influences academic performance (Williams et al., 2014). This is consistent with social and behavioral theories, which suggest that individual behaviors are influenced by the social and environmental dynamics around them (Bandura, 1986). Therefore, we expect that peer pressure will mediate the relationship between study stress and intention to use AI tools. Hence, the following mediation hypothesis is proposed:

H2:

The relationship between study stress and intention to use AI tools will be mediated by peer pressure.

6. Ethical Perceptions and Concern for Use of AI Tools

Given that AI tools can act as a double-edged sword (Imtiaz et al., 2024), higher education institutions struggle to resolve ethical dilemmas while maintaining academic integrity (McGrath et al., 2024). Academic integrity is a fundamental value in the education system, which includes honesty, fairness, trust, and responsibility in all scientific endeavors and academic learning (Abubakari, 2024; Acosta-Enriquez et al., 2024).

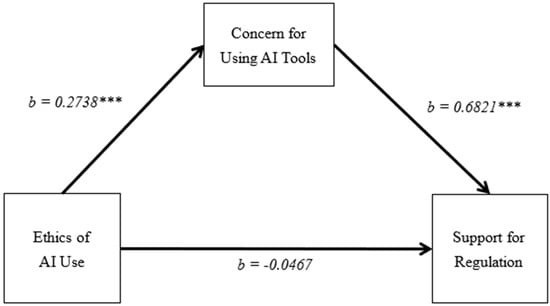

From this perspective, the current trends in using AI tools by college students pose ethical challenges. Perceptions on ethics in AI use are likely to lead to students’ support for regulation from their universities. Such perceptions of the need for regulation can be the results of the desire to use AI tools fairly without concern for potential negative consequences. Research has revealed that students often struggle with the idea of relying on AI tools to generate texts or for writing purposes or other things that facilitate students’ academic work due to ethical concerns (A. Nguyen et al., 2023; Reiss, 2021). However, this can at times manifest in the form of cheating or plagiarism with or without awareness of the potential consequences, especially when university policies are unclear. When students are concerned about the consequences, such concern can lead to misuse or avoidance of these tools (Vázquez-Parra et al., 2024). Students’ ethical perceptions of using AI tools vary according to the individual’s societal norms and values. When students perceive AI tools as ethically questionable, this creates concerns about misuse, for example, which leads to anxiety about using these tools (Acosta-Enriquez et al., 2024). Thus, those students who are concerned about ethical aspects of AI use are more likely to support regulation from their universities. Additionally, concerns about privacy can be related to ethical perceptions of AI tools, with studies revealing that many students feel uncomfortable with the information collection practices of AI tools such as ChatGPT, especially the sharing of personal information, due to fears of misuse or violation (A. Nguyen et al., 2023). In summary, we expect that the relationship between ethical use of AI and support for regulation would be mediated by concern for using AI tools. Hence, we propose the following mediation hypothesis:

H3:

The relationship between ethical perceptions and support for regulation will be mediated by concern for using AI tools.

7. Methodology

7.1. Research Design

Given the purpose of the study, an online survey was conducted among college students to examine their use and perceptions of AI tools in UAE universities. The survey questionnaire was designed based on a literature review to capture key aspects of AI tool usage and key perception variables, such as perceived usefulness, ease of use, ethical concerns, academic benefits, and behavioral intention toward AI adoption. Mediation models were developed and tested to assess the relationships between the key perception variables. This approach allowed for a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms shaping students’ perceptions of AI tools.

7.2. Study Respondents

This study employed an online survey method among students in UAE universities.

Following IRB approval, the survey questionnaire was uploaded onto the Qualtrics survey platform, and the survey link was active for less than one month, ending in late November of 2024. To minimize selection bias, participants were recruited through university networks, where faculty members and administrators shared the survey link via institutional emails. This approach ensured a diverse sample from various academic backgrounds and geographic locations in the UAE. A total of 822 effective responses were collected from seven universities in the five UAE states (i.e., Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah, Ajman, and Ras Al Khaimah). Thus, the survey covered broad geographical areas in the UAE (See Table 1 for demographics of survey participants).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of survey participants (N = 822).

7.3. Questionnaire Development

The questionnaire was written in English and Arabic. Two bilingual researchers proofread both Arabic and English versions to secure consistency in the questionnaire. Participants were advised to use the English version if their primary language was not Arabic.

The questionnaire consisted of three sections. The first section briefly introduced the survey to the study participants. The second section included demographic questions, as well as descriptive questions about AI tools. The third question included research questions to measure the variables in the study. The questionnaire was active for one month, and data collection ended in late November of 2024.

7.4. Measures

The instrument used in this study was a combination of new items developed by the researchers and items purposely modified from existing survey-based, empirical studies for the purpose of this study. The frequency of AI tool usage was measured by a single question, “How frequently do you use AI tools for academic purposes?” with responses including daily, weekly, monthly, or less than monthly. Familiarity with AI tools was measured by a single question, “Overall, how familiar/unfamiliar are you with AI tools such as ChatGPT?” with responses measured on a 7-point bipolar scale, from very unfamiliar to very familiar. Number of AI tools used was measured by a single question, “How many AI tools do you use, regardless of frequency of use?” with responses including 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or more than 6 AI tools. Awareness of AI tool use guidelines was measured by a single question, “Have you ever heard about guidelines from your professors regarding the use of AI tools?” with responses including yes, no, and not sure. All other research questions used 7-point Likert or bipolar scale items. Stress in this study was defined as felt psychological distress experienced by students due to academic challenges, measured by five items (M = 3.98, SD = 1.44, α = 0.83). Knowledge about AI tools was operationally defined as the knowledge, awareness, and experience of AI tools, measured by five items (M = 5.14, SD = 1.42, α = 0.88). The usefulness of AI tools was defined as the perceived usefulness, help, and enhancement of learning effectiveness, measured by four items (M = 5.14, SD = 1.42, α = 0.89). The benefit of AI tools was defined as the perceived benefits of AI tools for study, measured by three items (M = 5.29, SD = 1.24, α = 0.87). Intention to use AI tools was defined as the perceived intention to use AI tools in the future, measured by three items (M = 5.22, SD = 1.39, α = 0.90). Peer pressure was defined as the social influence exerted by friends, encouraging an individual to adopt behaviors or attitudes, measured by four items (M = 5.29, SD = 1.24, α = 0.88). The ethics of using AI tools was defined as perceived ethics of AI use, referring to an individual’s concerns and apprehensions regarding the ethical implications of using AI tools (M = 4.98, SD = 1.44, α = 0.75). Support for university regulation of the use of AI tools was defined as an individual’s agreement with the university that established guidelines, restrictions, or ethical standards for the use of AI tools in academic settings, measured by three items (M = 4.98, SD = 1.29, α = 0.90). Concern about using AI tools was defined as an individual’s apprehensions regarding the ethical, academic, and personal implications of AI use, measured by four items (M = 4.46, SD = 1.58, α = 0.82). All variables are presented in Appendix A, including the question items, factor loadings, composite reliability, and average variance extracted.

8. Results

8.1. Sample Characteristics

The initial original sample included 1150 students after excluding 183 incomplete responses, but 235 (20.4%) students indicated that they did not use any AI tools. Thus, the responses from 822 students were used for data analysis in this study. Seven universities from five emirates (Abu Dharbi, Ajman, Al Ain, Dubai, Las Al Khaima, and Sharjah) participated in this study. The mean age of the respondents was 22.32 years of age (SD = 5.75), and 61% (n = 499) were female. By semester standing, participants identified their standing as freshmen, 40% (n = 329); sophomores, 19% (n = 153); juniors, 17% (n = 141); seniors, 15% (n = 128); and graduate students, 9% (n = 71). The participants were from a wide variety of majors; 10% were engineering majors (n = 84), 23% were majoring in business and/or economics (n = 185), 18% were majoring in the social sciences (n = 147), 7% were majoring in health sciences, which included pharmacy, dentistry, and nursing majors (n = 54), 8% were arts and humanities majors (n = 69), and 34% were education majors (n = 34). This demographic composition provided a diverse regional and educational background among the study participants.

8.2. Descriptive Statistics

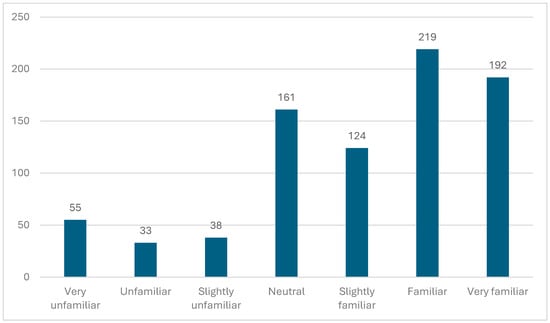

Figure 1 shows the students’ familiarity with AI tools. The question was “how familiar/unfamiliar are you with AI tools such as ChatGPT?” The majority of students reported themselves as familiar or very familiar with AI tools. Out of a total of 822 participants, 192 (23.4%) participants reported themselves as “very familiar”; 219 participants (26.6%), “familiar”; 124 (15.1%) participants, “slightly familiar”; 161 (19.6%) participants, “neutral”; 38 (4.6%) participants, “slightly familiar”; 33 (4.0%) respondents, “unfamiliar”; and 55 (6.7%) respondents, “very unfamiliar.” These results indicate that a large proportion of the sample had a moderate-to-high level of familiarity with AI tools, with more than half of the participants (50%) reporting being at least “slightly familiar” or higher. A t-test showed no significant difference between male (M = 4.96, SD = 1.74) and female (M = 5.12, SD = 1.65) participants for familiarity with AI tools, t = −1.35, p > 0.05.

Figure 1.

How familiar or unfamiliar are you with AI tools such as ChatGPT? (n = 822).

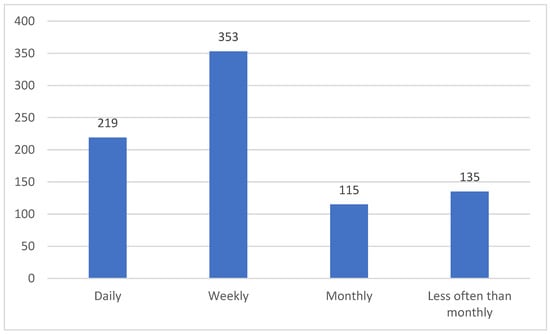

Figure 2 presents how frequently students use AI tools for academic purposes. Responses were categorized into four frequency levels: “daily”, “weekly”, “monthly”, and “less than monthly”. Of the total 822 participants, 219 (26.6%) participants used AI tools daily; 353 (42.9%) participants used them weekly; 115 (14.0%) participants, monthly; and 135 (16.4%) participants, less often than monthly. Cumulatively, a significant number of participants (572 participants or 69.6%) used AI tools either daily or weekly.

Figure 2.

How frequently do you use AI tools for academic purposes? (n = 822).

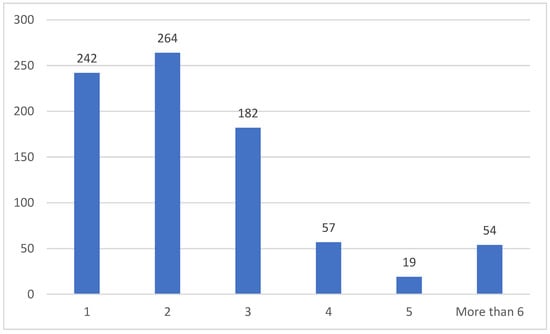

Figure 3 shows the number of AI tools students use for academic purposes. The majority of students used more than one AI tool. Of the participants, 246 (29.5%) participants used one AI tool; 264 (32.2%) participants, two AI tools; 182 (22.2%) participants used three AI tools; 57 (7.0%) participants, four AI tools; 19 (2.3%) participants, five AI tools; and 54 (6.6%), more than six AI tools.

Figure 3.

How many AI tools do you use? (n = 822).

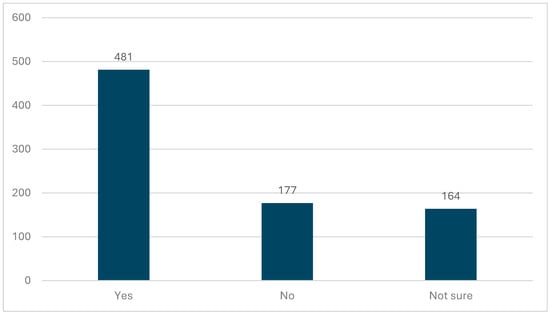

Figure 4 shows whether students have heard about the guidelines or policies on the use of AI tools from their professors. Responses were categorized into three options: “yes”, “no”, and “not sure”. Out of the total 822 participants, the majority of participants, 481 (58.5%) participants, reported that they were aware of the guidelines on the use of AI tools from their professors; 177 (21.5%) participants indicated that they did not hear about any guidelines or policies on the use of AI tools; and 164 (20.0%) participants were not sure whether they heard the guidelines. These results show that while more than half of the participants heard about the guidelines, a significant number of the participants did not hear or were not sure whether they heard about the guidelines.

Figure 4.

Have you heard about any guidelines on AI use from professors? (n = 822).

8.3. Hypothesis Testing

A series of mediation analyses was performed to test the proposed hypotheses using the PRCESS macro procedure Model 4 in SPSS Version 22.0 (Hayes, 2022). All three mediation models tested were based on 822 participants. The results of the multicollinearity tests showed no significant issue of multicollinearity between the predictor variables in all three models; VIF values ranged from 1.022 to 1.130. The condition indices were below the normally adopted threshold of 10, which suggests acceptable levels of collinearity.

H1 predicted that the relationship between students’ knowledge about AI tools and the perceived usefulness of AI tools would likely to be mediated by the perceived benefits of using AI tools (see Table 2 for means and standard deviations for variables). The analysis results indicated that knowledge significantly predicted benefits, b = 0.5128, SE = 0.0496, t = 10.3430, p < 0.001 (see Table 2 and Table 3 and Figure 5 for mediation analysis results for H1). The model for 11.54% of the variance in benefits (R2 = 0.1154, F(1, 820) = 106.978 accounted, p < 0.001). Knowledge was a strong predictor of usefulness, b = 0.5070, SE = 0.0309, t = 16.4016, p < 0.001. Benefits also had a significant effect on usefulness, b = 0.1807, SE = 0.0205, t = 8.8247, p < 0.001. Together, knowledge and benefits explained 38.06% of the variance in usefulness, R2 = 0.3806, F(2, 819) = 251.656, p < 0.001. The indirect effect of knowledge on usefulness through benefits was significant, b = 0.0927, SE = 0.0162, 95% CI [0.0639, 0.1276]. The direct effect of knowledge on usefulness remained significant, b = 0.5070, SE = 0.0309, 95% CI [0.4463, 0.5677]. These results suggest that knowledge influences usefulness both directly and indirectly through benefits. Thus, H1 was supported by data.

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients for H1.

Table 3.

Means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients for H2.

Figure 5.

The relationship between knowledge of AI tools and usefulness of AI tools mediated by perceived benefits of AI tools. *** p < 0.001.

H2 predicted that the relationship between study stress and intention to use AI tools would be mediated by peer pressure (see Table 3 for means and standard deviations). The regression analysis revealed a significant relationship between stress and peer pressure, b = 0.1346, SE = 0.0315, t = 4.2735, p < 0.001 (see Table 4 and Table 5, and Figure 6 for mediation analysis results for H2). The model explained 2.18% of the variance in peer pressure, R2 = 0.0218, F(1, 820) = 18.263, p < 0.001. The regression showed that peer influence significantly predicted intention, b = 0.6090, SE = 0.0286, t = 21.3003, p < 0.001, while stress had a marginally significant effect, b = 0.0505, SE = 0.0261, t = 1.9363, p = 0.053. The model accounted for 36.96% of the variance in intention, R2 = 0.3696, F(2, 819) = 240.043, p < 0.001. The indirect effect of stress on intention through peer pressure was significant, b = 0.0820, SE = 0.0219, 95% CI [0.0406, 0.1273]. However, the direct effect of stress on intention was not significant, b = 0.0505, SE = 0.0261, 95% CI [−0.0007, 0.1017]. These results indicate that peer pressure fully mediates the relationship between stress and intention. Thus, H2 was supported by data.

Table 4.

Means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients for H3.

Table 5.

H1 mediation results for knowledge, benefits, and usefulness.

Figure 6.

The relationship between study stress and intention to use AI tools mediated by peer pressure. *** p < 0.001.

H3 predicted that the relationship between perceived ethics about using AI tools and students’ support for regulation would be mediated concern for using AI tools (see Table 4 for means and standard deviations). The analysis showed the significant relationship between ethics and concern, b = 0.2738, SE = 0.0392, t = 6.9803, p < 0.001 (see Table 6 and Table 7 and Figure 7 for mediation analysis results). The model explained a small portion of the variance in concern, R2 = 0.0561, with the overall model being significant, F(1, 820) = 48.7244, p < 0.001. The relationship between ethics and support was not significant, b = −0.0467, SE = 0.0389, t = −1.2009, p = 0.2302. However, the relationship between concern and support was significant, b = 0.6821, SE = 0.0336, t = 20.2719, p < 0.001. The model explaining support accounted for 34.15% of the variance, R2 = 0.3415, and the overall model was significant, F(2, 819) = 212.3408, p < 0.001. The direct effect of ethics on support was not significant, but there was a significant indirect effect through concern. The indirect effect was b = 0.1868, SE = 0.0334, 95% CI [0.1234, 0.2552], indicating that concern fully mediated the relationship between ethics and support. Thus, H3 was supported.

Table 6.

H2 mediation analysis results for stress, peer pressure, and intention.

Table 7.

H3 mediation analysis results for ethics, concern, and support.

Figure 7.

The relationship between perceived ethics of AI use and support for regulation mediated by concern for using AI tools. *** p < 0.001.

9. Conclusions

This study explored college student perspectives about AI tools in UAE universities using a survey method. The survey showed that the use of AI tools is widespread among UAE colleges. The results showed that a significant number of college students use AI tools and are familiar with the AI tools they use regularly. Data analyses also supported the proposed mediation models and identified mediating variables leading to student perceptions on AI tools. This study contributes to the understanding of how college students use and perceive AI tools for academic purposes and provides implications for establishing AI-related policies in higher education in the UAE.

Existing empirical studies have primarily focused on identifying variables related to students’ perceptions and attitudes toward AI tools (e.g., Abbas et al., 2024; Johnston et al., 2024; McGrath et al., 2024; Ravšelj et al., 2025), while studies examining the relationships among these variables remain sporadic in the higher education environment (e.g., Abbas et al., 2024; Acosta-Enriquez et al., 2024; Niu et al., 2024). Moreover, few empirical data are available on the use and perceptions of AI tools in the UAE higher education context. This study sought to address this gap by providing insights and empirical data relevant to UAE higher education and policymakers.

This study surveyed college students from a diverse representation of academic disciplines and demographics in the UAE. Descriptive statistics showed that many of the participants use AI tools on a daily or weekly basis and perceive that they are familiar with the AI tools they use. They also expressed concerns about the potential negative consequences. Despite the concerns, less than half of the participants said that they had heard about the guidelines for using AI tools from their professors. Overall, the descriptive statistics suggest the prevalence of the use of AI tools and uncertainty in terms of ethics and potential consequences arising from using AI tools.

The mediation models proposed were designed to uncover the underlying mechanism in student perceptions on AI tools. In testing H1, the mediation analysis indicated a strong relationship between students’ knowledge of AI tools and perceived usefulness, and this relationship is mediated by the perception of the benefits of AI tools. Specifically, this result suggests that the more knowledgeable students are about AI tools, the more they perceive AI tools as useful, but this relationship is strongly contingent on their perception about the benefits derived from it. Accordingly, it may not be sufficient for students to become knowledgeable about AI tools; they have to perceive some tangible benefits if they are to consider AI tools useful. To the degree that students perceive AI tools as beneficial to their work, they are more likely to use them for academic purposes (Abbas et al., 2024; Acosta-Enriquez et al., 2024; Alenezi, 2021). This result points to the pragmatic approach of university students. Perceived benefits can be a key for students’ perception of the usefulness of AI tools. These findings provide important practical implications for policymakers and educators in higher education. Since concern about AI tools plays an important role in shaping students’ support for regulation, universities and policymakers can make further efforts to increase the awareness of AI-related ethical issues to encourage more informed and responsible AI usage.

In testing H2, mediation analysis also found that academic stress influences students’ intentions to use AI tools through the full mediator of peer pressure. In other words, high academic stress could make students use AI tools largely because of their peers. Students may encourage others to use AI tools, or they may simply be pressured to use AI tools when observing others using AI tools to enhance their academic performance. Such incidences are more likely especially when students are under time pressure (Abbas et al., 2024; Acosta-Enriquez et al., 2024). Examples include using AI-enhanced study resources or AI-assisted writing support systems to better manage or take control of academic pressures. The social dimension of peer pressure cannot be abandoned either because sometimes students receive help from their better-off peers in regard to how they cope with academic issues efficiently. So, if some of them observe their peers doing this to reduce stress and perform better academically, they are likely to reproduce the same behavior. These findings have some practical implications for educators and university administrators. Universities can develop awareness campaigns and peer mentoring programs to promote ethical AI use while encouraging a supportive academic environment. Educators may also need to integrate discussions on responsible AI usage into coursework to ensure that students make informed decisions rather than succumbing to peer-driven pressures.

For H3, mediation analysis further found that ethical perceptions significantly influence students’ support for AI regulation, mediated by concerns about misuse and privacy. Despite the fact that many students in this study perceived the benefits of using AI tools for academic purposes, they also perceived ethical concerns such as the possibility of plagiarism or their professors detecting the use of an AI tool (Chaudhry & Kazim, 2021). More specifically, ethical issues associated with the use and potential misuse of AI tools may make students support the regulation of AI. For example, students may worry that using AI tools will result in violations of academic integrity one way or another. This is particularly concerning, given that many of them are not aware of clear guidelines about using AI tools in academic work from their professors or university. This is why clearly explained instructions and policies are needed that ensure responsible and ethical use within the educational process. From a practical perspective, universities should proactively guide students about responsible AI use, including ethical considerations, academic integrity, and data privacy. Additionally, faculty members can also provide the necessary resources to communicate AI policies effectively to students such that when the use of AI is unclear, they can have a clear understanding of acceptable AI practices and the potential consequences of misuse.

This research has several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, using a convenience sampling method, this research surveyed 822 respondents from seven universities in the UAE, which therefore limits the generalizability of the findings. Future studies can benefit by employing probability sampling techniques to ensure a more representative sample. Furthermore, future studies may need to include more universities across different emirates, as well as incorporate a diverse range of academic disciplines to provide a more holistic view of AI tool adoption and its implications in higher education. Second, the cross-sectional nature of this survey captured students’ perceptions and AI tool usage at a single point in time. AI tools are rapidly developing, while the policies of using AI tools are not clearly established in academia, including the universities in the UAE. Future studies may utilize longitudinal methods to capture the changing AI environment in using AI tools in academia. A longitudinal research design would allow us to track changes in students’ perceptions and usage of AI by providing insights into emerging trends, shifting ethical perceptions, and evolving institutional policies in higher education. Third, this study used a self-reported questionnaire to assess students’ perceptions on AI tools. Given the ethical and cultural sensitivities surrounding the use of AI tools in academia, there might have been a certain degree of social desirability bias involved in the students’ reports. For example, some students might have underreported or overstated their AI tool usage and might have given more socially acceptable answers. To address this issue, future studies may need to incorporate social desirability scales to control for potential social desirability biases. Finally, future research could investigate the role of faculty and institutions in shaping students’ AI adoption behaviors, as faculty and university policies play a critical role in guiding how AI tools are utilized in academic environments.

In summary, this research provides important insights into the variables that influence the use of AI tools by university students in the UAE. It illustrates the interrelations between these variables. With the continuous development of AI and its impact on higher education, there is an increasing need to understand how college students use and perceive these technologies. As institutions of higher learning grapple with issues relating to AI, the results of this study can help establish guidelines and policies for educational institutions and lawmakers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and S.Y.L.; methodology, A.S. and S.Y.L.; software, S.Y.L.; validation, S.Y.L.; formal analysis, S.Y.L. and A.S.; investigation, A.S.; resources, A.S.; data curation, A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.; writing—review and editing, S.Y.L. and S.B.R.; visualization, S.Y.L.; supervision, S.Y.L. and S.B.R.; project administration, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Ajman University, the United Arab Emirates (protocol code Ma-F-H-4-Sep, approved on 4 September 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data of this study is available upon request to the correspondent author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Sample questions used in the survey.

Table A1.

Sample questions used in the survey.

| Variables | Items | Standaridized Loadings | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of AI tool use | How frequently do you use AI tools for academic purposes? | - | - | - |

| Familiarity with AI tools | Overall, how familiar or unfamiliar are you with AI tools such as ChatGPT? | - | - | - |

| AI tool use guidelines | Have you ever heard any guidelines from your professors regarding the use of AI tools? | - | - | - |

| Study stress |

| 0.75 | 0.92 | 0.58 |

| 0.82 | |||

| 0.78 | |||

| 0.71 | |||

| 0.84 | |||

| Knowledge of AI tools |

| 0.68 | 0.81 | 0.53 |

| 0.75 | |||

| 0.71 | |||

| 0.69 | |||

| 0.73 | |||

| Usefulness of AI tools |

| 0.68 | 0.81 | 0.53 |

| 0.75 | |||

| 0.71 | |||

| 0.69 | |||

| Benefits of AI tools |

| 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.93 |

| 0.97 | |||

| 0.95 | |||

| Intention to use AI tools |

| 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.83 |

| 0.89 | |||

| 0.92 | |||

| Peer Pressure |

| 0.72 | 0.82 | 0.58 |

| 0.68 | |||

| 0.75 | |||

| 0.71 | |||

| Ethics |

| 0.73 | 0.80 | 0.54 |

| 0.69 | |||

| 0.68 | |||

| 0.70 | |||

| Support for regulation |

| 0.73 | 0.80 | 0.54 |

| 0.69 | |||

| 0.68 | |||

| Concern about using AI tools |

| 0.67 | 0.72 | 0.58 |

| 0.68 | |||

| 0.69 | |||

| 0.66 |

Note: CR: Composite reliability; AVE: Average variance extracted.

References

- Abbas, M., Jam, F. A., & Khan, T. I. (2024). Is it harmful or helpful? Examining the causes and consequences of generative AI usage among university students. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 21(10), 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakari, M. S. (2024). Overviewing the maze of research integrity and false positives within AI-enabled detectors: Grammarly dilemma in academic writing. In Advances in educational technologies and instructional design book series (pp. 335–366). Chapter 13. IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Enriquez, B. G., Arbulú Ballesteros, M. A., Arbulu Perez Vargas, C. G., Ulloa, M. N. O., Ulloa, C. R. G., Romero, J. M. P., Jaramillo, N. D. G., Orellana, H. U. C., Anzoátegui, D. X. A., & Roca, C. L. (2024). Knowledge, attitudes, and perceived ethics regarding the use of ChatGPT among Generation Z university students. International Journal of Educational Integrity, 20, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenezi, M. (2021). Deep dive into digital transformation in higher education institutions. Education Sciences, 11(12), 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artificial Intelligence Office. (n.d.). Artificial intelligence office, UAE. United Arab Emirates Government. Available online: https://ai.gov.ae/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1985-98423-000 (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Benuyenah, V., & Dewnarain, S. (2024). Students’ intention to engage with ChatGPT and artificial intelligence in higher education business studies programs: An initial qualitative exploration. International Journal of Distance Education Technologies, 22(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J., Tang, C., & Kennedy, G. (2022). Teaching for quality learning at university (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Changalima, I. A., Amani, D., & Ismail, I. J. (2024). Social influence and information quality on generative AI use among business students. The International Journal of Management Education, 22(3), 101063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, M., & Kazim, E. (2021). Artificial intelligence in education (AIEd): A high-level academic and industry note. AI and Ethics, 2, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L., Chen, P., & Lin, Z. (2020). Artificial intelligence in education: A review. IEEE Access, 8, 75272–75275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhi, F., Jeljeli, R., Aburezeq, I., Dweikat, F. F., Al-shami, S. A., & Slamene, R. (2023). Analyzing the students’ views, concerns, and perceived ethics about ChatGPT usage. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 5, 100180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, A. I., Al Radaideh, A., Singh Sisodia, G., Mathew, A., & Jimber del Río, J. A. (2022). Managing university e-learning environments and academic achievement in the United Arab Emirates: An instructor and student perspective. PLoS ONE, 17(5), e0268338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D., & Straub, D. W. (2000). The relative importance of perceived ease of use in IS adoption: A study of e-commerce adoption. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 1(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H. (2024). Promoting students’ creative and design thinking with generative AI-supported co-regulated learning: Evidence from digital game development projects in healthcare courses. Educational Technology & Society, 27(4), 487–502. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, F., Münscher, J.-C., Daseking, M., & Telle, N.-T. (2025). The technology acceptance model and adopter type analysis in the context of artificial intelligence. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 7, 1496518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imtiaz, Q., Altaf, M., Pérez Berlan, R., Lee, M. D., Ahmad, S., & Salman, H. (2024). Artificial intelligence: A double-edged sword for the education and environment of the global market. Educational Administration: Theory and Practice, 30(6), 3181–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, H., Wells, R. F., Shanks, E. M., Boey, T., & Parsons, B. N. (2024). Student perspectives on the use of generative artificial intelligence technologies in higher education. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 20(2), 16–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köchling, A., & Wehner, M. C. (2023). Better explaining the benefits: Why AI? Analyzing the impact of explaining the benefits of AI-supported selection on applicant responses. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 31(1), 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzuki, Widiati, U., Rusdin, D., Darwin, & Indrawati, I. (2023). The impact of AI writing tools on the content and organization of students’ writing: EFL teachers’ perspective. Cogent Education, 10(2), 2236469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, C., Farazouli, A., & Cerratto-Pargman, T. (2024). Generative AI chatbots in higher education: A review of an emerging research area. Journal of Educational Technology, 88(4), 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A., Ngo, H. N., Hong, Y., Dang, B., & Nguyen, B.-P. T. (2023). Ethical principles for artificial intelligence in education. Education and Information Technologies, 28(6), 4221–4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H. M., & Goto, D. (2024). Unmasking academic cheating behavior in the artificial intelligence era: Evidence from Vietnamese undergraduates. Education and Information Technologies, 29, 15999–16025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, W., Zhang, W., Zhang, C., & Chen, X. (2024). The role of artificial intelligence autonomy in higher education: A uses and gratification perspective. Sustainability, 16(3), 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polak, P., & Anshari, M. (2024). Exploring the multifaceted impacts of artificial intelligence on public organizations, business, and society. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravšelj, D., Keržič, D., Tomaževič, N., Umek, L., Brezovar, N., Iahad, N. A., Abdulla, A. A., Akopyan, A., Segura, M. W. A., AlHumaid, J., Allam, M. F., Alló, M., Andoh, R. P. K., Andronic, O., Arthur, Y. D., Aydın, F., Badran, A., Balbontín-Alvarado, R., Saad, H. B., … Aristovnik, A. (2025). Higher education students’ perceptions of ChatGPT: A global study of early reactions. PLoS ONE, 20(2), e0315011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, M. J. (2021). The use of AI in education: Practicalities and ethical considerations. London Review of Education, 19(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodzi, Z. M., Rahman, A. A., Razali, I. N., Nazri, I. S. M., & Abd Gani, A. F. (2023). Unraveling the drivers of artificial intelligence (AI) adoption in higher education. International Conference on University Teaching and Learning, 1, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. M. (1962). Diffusion of innovations (1st ed.). Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Santosh, K. C. (2020). AI-driven tools for coronavirus outbreak: Need of active learning and cross-population train/test models on multitudinal/multimodal data. Journal of Medical Systems, 44(5), 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L., Ding, A.-C., & Choi, I. (2024). Investigating teachers’ use of an AI-enabled system and their perceptions of AI integration in science classrooms: A case study. Education Sciences, 14(11), 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Parra, J. C., Henao-Rodríguez, C., Lis-Gutiérrez, J. P., & Palomino-Gámez, S. (2024). Importance of university students’ perception of adoption and training in artificial intelligence tools. Societies, 14(8), 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S., Tanner, M., Beard, J., & Chacko, J. (2014). Academic misconduct among business students: A comparison of the US and UAE. Journal of Academic Ethics, 12(1), 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurt, E., & Kasarci, I. (2024). A questionnaire of artificial intelligence use motives: A contribution to investigating the connection between AI and motivation. International Journal of Technology in Education, 7(3), 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).