Fostering Action Competence Through Emancipatory, School-Based Environmental Projects: A Bildung Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Action Competence: From Knowledge to Participation

2.2. Bildung as a Theoretical Foundation

- (1)

- Critical reflection, which focuses on students’ ability to question causes, connect multiple factors, and reconsider their role in solving problems;

- (2)

- Co-creation with stakeholders, which highlights the democratic process of planning, negotiating, and refining solutions with peers, teachers, and local actors; and

- (3)

- Social responsibility, which emphasizes that students see their actions as meaningful contributions to the community beyond themselves.

2.3. Emancipatory Approach in Environmental Education

- (1)

- Dialogic learning, in which students, teachers, and stakeholders engaged in mutual dialogue to identify and analyze environmental issues;

- (2)

- Shared decision-making, which emphasized students’ autonomy and collaboration with others to plan and implement actions; and

- (3)

- Collective reflection and responsibility, encouraging learners to evaluate outcomes, recognize interdependence, and sustain improvements through democratic participation (Cincera et al., 2020; Schusler & Krasny, 2010).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Research Site and Context

3.3. Participants and Ethical Considerations

3.4. Summary of the Intervention—Emancipatory Approach

3.5. Data Collection Tools and Procedures

3.5.1. Student Action Competence Questionnaire

3.5.2. Students’ Worksheets and Reflective Journals

- Surveying environmental problems,

- Questioning and analyzing the selected issue,

- Collaborating with stakeholders to set goals,

- Analyzing the environmental problem,

- Proposing solutions and implementation, and

- Summarizing the Environmental project.

3.6. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Overview of Student Environmental Projects

4.2. Overall Action Competence Levels After the Emancipatory Environmental Projects

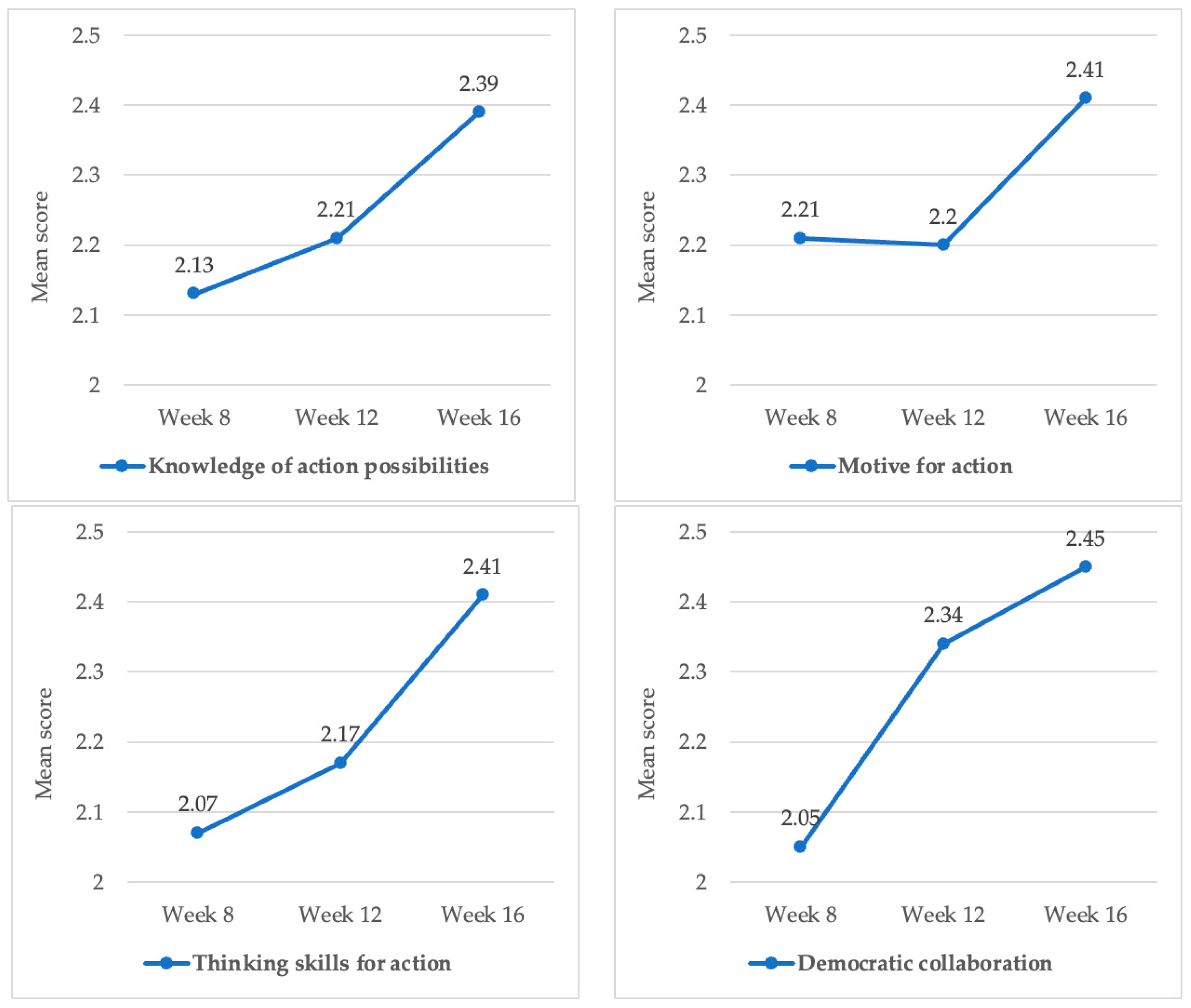

4.3. Component Analysis of Action Competence

4.4. Qualitative Findings Interpreted Through the Bildung Framework

4.4.1. Critical Reflection

- Theme 1: Questioning Causes and Linking Multiple Factors

- Theme 2: Recognizing Health and Safety Risks for the Common Good

4.4.2. Co-Creation with Stakeholders

- Theme 1: Negotiating Solutions and Coordinating with Authorities

- Theme 2: Revising Plans and Creating Two-Way Communication Channels

4.4.3. Social Responsibility

- Theme 1: Sustaining Improvements and Involving Others

- Theme 2: Recognizing Personal Responsibility and Disciplined Citizenship

5. Discussion

5.1. Dialogic and Participatory Learning Fostered Reflexive Agency Across All Dimensions of Action Competence

5.2. Collective and Ethically Grounded Collaboration Nurtured Democratic Competence as a Core Expression of Bildung

6. Implications

6.1. Integrate Democratic Participation into Environmental Learning Contexts

6.2. Adopt an Emancipatory Rather than Purely Instrumental Pedagogical Stance

6.3. Foster Collective and Sociocultural Learning Through Community Engagement

7. Limitations and Future Directions

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Checklist | Score Level | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Knowledge of action possibilities | |||

| 1. I can identify environmental issues, causes, and impacts within my school community. | |||

| 2. I can propose appropriate solutions for addressing environmental problems in my school community. | |||

| 3. I can outline methods to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of the chosen solutions. | |||

| Motive for action | |||

| 4. I am committed to solving environmental issues. | |||

| 5. I persist despite obstacles. | |||

| 6. I am confident in my abilities. | |||

| 7. I can take the lead in environmental actions without hesitation. | |||

| 8. I can encourage others to participate in environmental initiatives. | |||

| 9. I am open to continuous learning and self-improvement. | |||

| 10. I view mistakes as opportunities for growth and learning. | |||

| Thinking skills for action | |||

| 11. I am careful and systematic in my planning. | |||

| 12. I acts responsibly according to the plan. | |||

| 13. I engages in reflective thinking throughout the action process. | |||

| 14. I adapt my action plan based on context, new insights, and reflections. | |||

| Democratic collaboration | |||

| 15. I collaborate with the community or stakeholders to establish shared goals for addressing environmental issues. | |||

| 16. I am open to diverse approaches from the community or stakeholders in solving environmental problems. | |||

| 17. I respect and accept group consensus. | |||

| 18. I makes decision collaboratively with the community or stakeholders to choose context-appropriate solutions. | |||

| 19. I take concrete actions and monitor the outcomes. | |||

| Date of Evaluation: | ……/……/…… | ||

References

- Ardoin, N. M., Bowers, A. W., & Gaillard, E. (2020). Environmental education outcomes for conservation: A systematic review. Biological Conservation, 241, 108224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G. (2002). How general can Bildung be? Reflections on the future of a neo-humanist educational ideal. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 36(3), 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiting, S., & Mogensen, F. (1999). Action competence and environmental education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 29(3), 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, M. (2024). Twinning of Bildung and competence in environmental and sustainability education. In P. P. Trifonas, & S. Jagger (Eds.), Handbook of curriculum theory, research, and practice (pp. 218–232). Springer International Handbooks of Education. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cincera, J., Johnson, B., Kroufek, R., Kolenatý, M., & Šimonová, P. (2020). Frames in outdoor environmental education programs: What we communicate and why we think it matters. Sustainability, 12(11), 4451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cincera, J., & Kovacikova, S. (2014). Being an EcoTeam member: Movers and fighters. Applied Environmental Education & Communication, 13(4), 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dittmer, L., Mugagga, F., Metternich, A., Schweizer-Ries, P., Asiimwe, G., & Riemer, M. (2017). “We can keep the fire burning”: Building action competence through environmental justice education in Uganda and Germany. Local Environment, 23(2), 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, K. M. (1997). Perspectives on environmental action: Reflection and revision through practical experience. The Journal of Environmental Education, 29(1), 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed (M. B. Ramos, Trans.; 30th anniversary ed.). Continuum. (Original work published 1970). [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, C. (2015). Beyond the decade: The global action program for education for sustainable development. Applied Environmental Education & Communication, 14(2), 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaikrasen, P., & Ketsing, J. (2025). Cultivating sense of place through place-based education: An innovative approach to education for sustainability in a Thai primary school. Education Sciences, 15(11), 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B. B., & Schnack, K. (1997). The action competence approach in environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 3(2), 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyburz-Graber, R. (2019). 50 years of environmental research from a European perspective. The Journal of Environmental Education, 50(4–6), 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Mogensen, F., & Schnack, K. (2010). The action competence approach and the “new” discourses of education for sustainable development, competence and quality criteria. Environmental Education Research, 16(1), 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2022). Are students ready to take on environmental challenges? OECD Publishing. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2022/12/are-students-ready-to-take-on-environmental-challenges_fbde6084/8abe655c-en.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Olsson, D., Gericke, N., Sass, W., & Pauw, J. B.-d. (2020). Self-perceived action competence for sustainability: The theoretical grounding and empirical validation of a novel research instrument. Environmental Education Research, 26(5), 742–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Sass, W., Boeve-de Pauw, J., Olsson, D., Gericke, N., Maeyer, S. D., & Van Petegem, P. (2020). Redefining action competence: The case of sustainable development. The Journal of Environmental Education, 51(4), 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schusler, T. M., & Krasny, M. E. (2010). Environmental action as context for youth development. The Journal of Environmental Education, 41(4), 208–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöström, J., Frerichs, N., Zuin, V. G., & Eilks, I. (2017). Use of the concept of Bildung in the international science education literature, its potential, and implications for teaching and learning. Studies in Science Education, 53(2), 165–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torsdottir, A. E., Olsson, D., Sinnes, A. T., & Wals, A. E. J. (2024). The relationship between student participation and students’ self-perceived action competence for sustainability in a whole school approach. Environmental Education Research, 30(8), 1308–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2016). Global education monitoring report 2016: Education for people and planet. UNESCO. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2020). Education for sustainable development: A roadmap. UNESCO. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374802 (accessed on 27 March 2020).

- Wals, A. E. J., Geerling-Eijff, F., Hubeek, F., van der Kroon, S., & Vader, J. (2008). All mixed up? Instrumental and emancipatory learning toward a more sustainable world: Considerations for EE policymakers. Applied Environmental Education & Communication, 7(3), 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A. E. J., & Jickling, B. (2002). “Sustainability” in higher education: From doublethink and newspeak to critical thinking and meaningful learning. Higher Education Policy, 15(2), 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheaton, M., Ardoin, N. M., Bowers, A. W., & Kannan, A. (2024). Sociocultural learning theories for social-ecological change. Environmental Education Research, 30(8), 1193–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Weeks | Main Learning Activities | Principles of the Emancipatory Approach | Corresponding Bildung Dimensions | Illustrative Examples/ Learning Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 Problem survey and awareness building | Students conducted site walks, observed environmental issues, and interviewed school stakeholders. | Dialogic learning—students and teachers engaged in open dialogue to explore authentic school problems and share initial perspectives. | Critical reflection—questioning assumptions and recognizing causes of school-based environmental problems. | Students identified issues such as waste accumulation and drainage problems through sensory exploration and stakeholder interviews. |

| 3–4 Issue selection and cause analysis | Group discussion and collaborative problem analysis to choose the most relevant issue for action. | Shared decision-making—students democratically negotiated priorities and selected feasible topics for collective action. | Critical reflection—Co-creation—linking multiple causes and connecting them to social and physical contexts. | Students analyzed root causes such as improper waste habits, poor drainage, and unsafe infrastructure. |

| 5–7 Solution design and planning | Students worked with stakeholders to co-design practical solutions and detailed action plans. | Shared decision-making—students exercised autonomy while negotiating resources and responsibilities with stakeholders. | Co-creation with stakeholders—collaborative planning and revising plans based on feedback. | Students planned actions like a bottle-recycling system, canal cleaning with district support, and repairs with maintenance staff. |

| 8–11 Implementation and collective action | Students executed their plans, collaborating with peers, teachers, and school staff. | Active participation within dialogic practice—students learned through action, interaction, and mutual support. | Social responsibility—taking ownership and acting for the common good. | Students organized cleaning rotations and mobilized peers to maintain shared areas. |

| 10–12 Monitoring and adjustment | Students assessed progress, reflected on outcomes, and refined strategies with guidance. | Collective reflection and responsibility—dialogue on successes and challenges; redefining goals together. | Critical reflection Social responsibility—evaluating actions and sustaining improvements. | Students monitored the effects of their actions and identified remaining issues. They adjusted their strategies and coordinating follow-up tasks with school staff. |

| 13–14 Presentation and community sharing | Students presented their project outcomes to peers and stakeholders. | Collective reflection and dialogue—sharing learning and acknowledging contributions of all participants. | Integration of all dimensions—reflection, co-creation, and responsibility converge through communication. | Students presented results and shared learning with peers and stakeholders. |

| 15–16 Evaluation and future commitment | Students synthesized learning experiences and reflected individually and collectively. | Collective reflection and empowerment—students articulate personal transformation and envision next steps. | Reflexive agency—self-formation leading to sustained ethical and social engagement. | Students wrote reflections and proposed continued recycling or maintenance programs. |

| Tool/Instrument | Source of Data | Type of Data | Purpose/Focus | Time of Collection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Student action competence questionnaire | 37 Grade 8 students | Quantitative | To measure four dimensions of students’ action competence: knowledge of action possibilities, motive for action, thinking skills for action, and democratic collaboration | Weeks 8, 12, and 16 |

| Students’ worksheets | Group work outputs | Qualitative | To document students’ processes of identifying problems, analyzing causes, designing solutions, and collaborating with stakeholders in school-based projects | Six worksheets: Weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, 9, and 14 |

| Group reflective journals | Group reflections | Qualitative | To capture students’ evolving reflections, teamwork, and development of critical awareness and responsibility during project implementation | Four journals: Weeks 2, 4, 8, and 15 |

| Dimension | Description | Example Codes | Sample Excerpts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Critical reflection | Evidence that students challenge assumptions and examine causes rather than accept problems at face value. |

| “What causes the litter to spread around the area?” “How does the littering problem affect people who live or walk around this area?” “How can everyone in the school help to dispose of waste properly or take part in solving this problem?” (Group 1) |

| Co-creation with stakeholders | Evidence that students work democratically with peers, teachers, or other stakeholders to develop and refine solutions. |

| “Put up signs and place trash bins in areas with heavy litter, and encourage people to exchange collected waste for lucky-draw coupons.” “Additional notes and recommendations from Teacher A (Teacher responsible for the student council): 1. Collect and compress plastic bottles, then exchange them for money or coupons. 2. Post ‘No Littering’ signs in various locations.” (Group 1) |

| Social responsibility | Evidence that students see their actions as contributions beyond themselves and show willingness to maintain change. |

| “After we cleaned the weeds, we agreed to do it weekly with janitors. We planned to get gloves and tools so everyone can help.” (Group 6) |

| Group | Project Title/Focus | Main Issue Addressed | Key Stakeholders Involved | Brief Project Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Bottle of Luck | Waste reduction and recycling | Scattered waste and improper trash disposal | Teacher responsible for the student council, janitors, peers, and subject teacher | Installed new bins and signage; created a coupon-exchange system (“bottle for luck”) to motivate waste sorting; surveyed satisfaction and adjusted plans based on stakeholder feedback. |

| 2. Cleaning the Canal | Water pollution and school sanitation | Dirty canal near the school compound | School principal, district office, janitors, peers, and subject teacher | Conducted clean-up activities, installed warning signs, and submitted letters to the district office requesting long-term canal maintenance. |

| 3. Happy Toilet | Restroom hygiene and odor control | Unclean and unpleasant restrooms | Building-management teacher, student council, janitors, peers, and subject teacher | Designed a “Happy Toilet” campaign using posters, QR-code feedback surveys, and online communication to improve cleanliness and user responsibility. |

| 4. Reducing Mosquito Breeding Grounds | Health and safety | Standing water and mosquito larvae | Subject teacher, janitors, and health-promotion committee | Inspected potential breeding sites, drained water, and educated peers about dengue prevention. |

| 5. Tile Repair | Campus safety and maintenance | Broken or uneven floor tiles | Maintenance staff, administrators, and subject teacher | Surveyed hazardous areas, mapped damaged tiles, and submitted improvement proposals to school management for repair prioritization. |

| 6. Weed Removal around Power Poles | School aesthetics and safety | Overgrown weeds near electrical poles | Janitors, maintenance staff, peers, and subject teacher | Organized regular weed-removal activities with janitors and classmates; developed a weekly maintenance schedule to sustain improvements. |

| 7. Eliminating Odors from Restroom Drainage System | Indoor air quality and hygiene | Odor and drainage problems in restrooms | Building-management teacher, janitors, peers, and subject teacher | Used charcoal to absorb odors around restroom drains and proposed a plan to redesign the drainage system for long-term improvement. |

| Competence Level | Week 8 | % | Week 12 | % | Week 16 | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High (45–57) | 11 | 29.73 | 15 | 40.54 | 28 | 75.68 |

| Moderate (32–44) | 22 | 59.46 | 21 | 56.76 | 8 | 21.62 |

| Low (19–31) | 4 | 10.81 | 1 | 2.70 | 1 | 2.70 |

| Total | 37 | 100 | 37 | 100 | 37 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ketchanok, S.; Ketsing, J. Fostering Action Competence Through Emancipatory, School-Based Environmental Projects: A Bildung Perspective. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1706. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121706

Ketchanok S, Ketsing J. Fostering Action Competence Through Emancipatory, School-Based Environmental Projects: A Bildung Perspective. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1706. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121706

Chicago/Turabian StyleKetchanok, Suchawadee, and Jeerawan Ketsing. 2025. "Fostering Action Competence Through Emancipatory, School-Based Environmental Projects: A Bildung Perspective" Education Sciences 15, no. 12: 1706. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121706

APA StyleKetchanok, S., & Ketsing, J. (2025). Fostering Action Competence Through Emancipatory, School-Based Environmental Projects: A Bildung Perspective. Education Sciences, 15(12), 1706. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121706