Integrating Exploratory Data Analysis and Explainable AI into Astronomy Education: A Fuzzy Approach to Data-Literate Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Phase 1 involves the selection and acquisition of data from open astronomical repositories such as NASA JPL Horizons, the Minor Planet Center, and ESA Gaia DR3, focusing first on comets and asteroids and later stellar datasets.

- Phase 2 addresses data preprocessing and enrichment, including the computation of orbital distances, magnitudes, and derived photometric parameters.

- Phase 3 consists of an EDA to uncover statistical patterns, temporal trends, and spatial relationships within the heliocentric and stellar contexts.

- Phase 4, Fuzzy C-Means clustering is applied to model uncertainty and identify fuzzy groupings of celestial objects based on their photometric and positional attributes.

- Phase 5 introduces the FAS-XAI framework, combining fuzzy logic, adaptive scoring, and XAI techniques such as LIME and feature importance analysis to interpret the results.

- How can EDA, fuzzy logic, and XAI be combined to create a reproducible and pedagogically meaningful workflow for astronomy education?

- What types of scientific and interpretative insights can students obtain when working directly with real orbital and stellar datasets?

- How does the FAS-XAI framework support students in understanding uncertainty, classification, and interpretability in data-driven contexts?

2. Related Work

2.1. Astronomy as a Gateway to Scientific Learning

2.2. Data-Driven Learning and the Integration of Computational Tools

2.3. Fuzzy Logic and Uncertainty Modeling in Education

2.4. XAI in Educational Contexts

2.5. Summary and Research Gap

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Dataset Construction

3.2. Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)

3.3. Fuzzy C-Means Clustering

3.4. Predictive and Explainable Modeling

3.4.1. Predictive Layer: XGBoost Classifier and Regressors

- 1.

- Multiclass Classification:

- 2.

- Regression-Based Fuzzy Reconstruction:

3.4.2. Explainability Layer: From Feature Importance to Local Interpretation

- Global explanations, using feature importance metrics derived from the XGBoost ensemble, allowed students to identify which astrophysical variables most strongly influenced the model’s predictions. Bar plots and aggregated importance scores provided visual insight into how color, brightness, or parallax contribute to stellar classification.

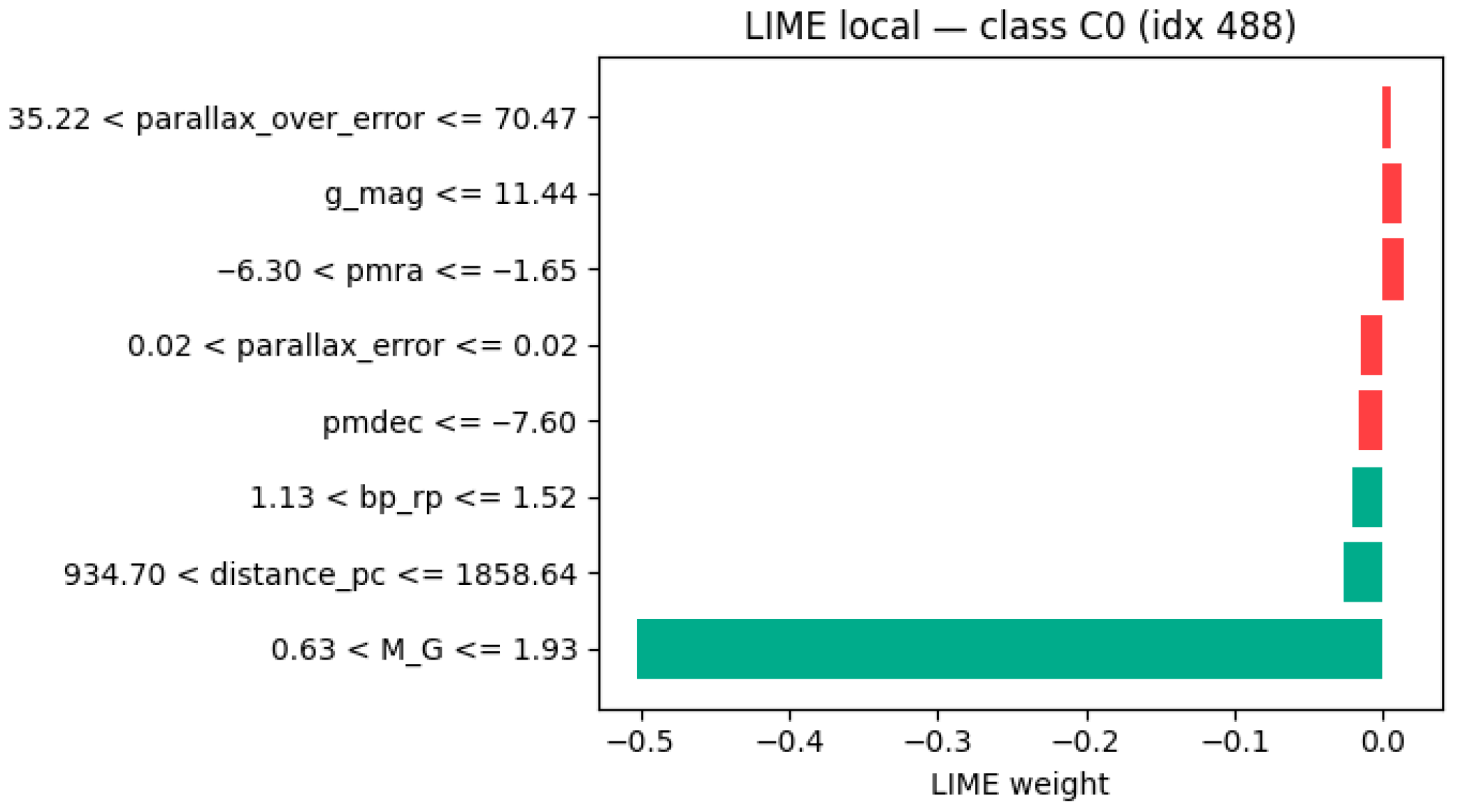

- Local explanations, based on LIME, were used to explore the behavior of the model around specific examples, representative stars or ambiguous data points. For each instance, LIME builds a locally weighted linear surrogate model:

3.5. Strategic Interpretation

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. EDA of the Case Study

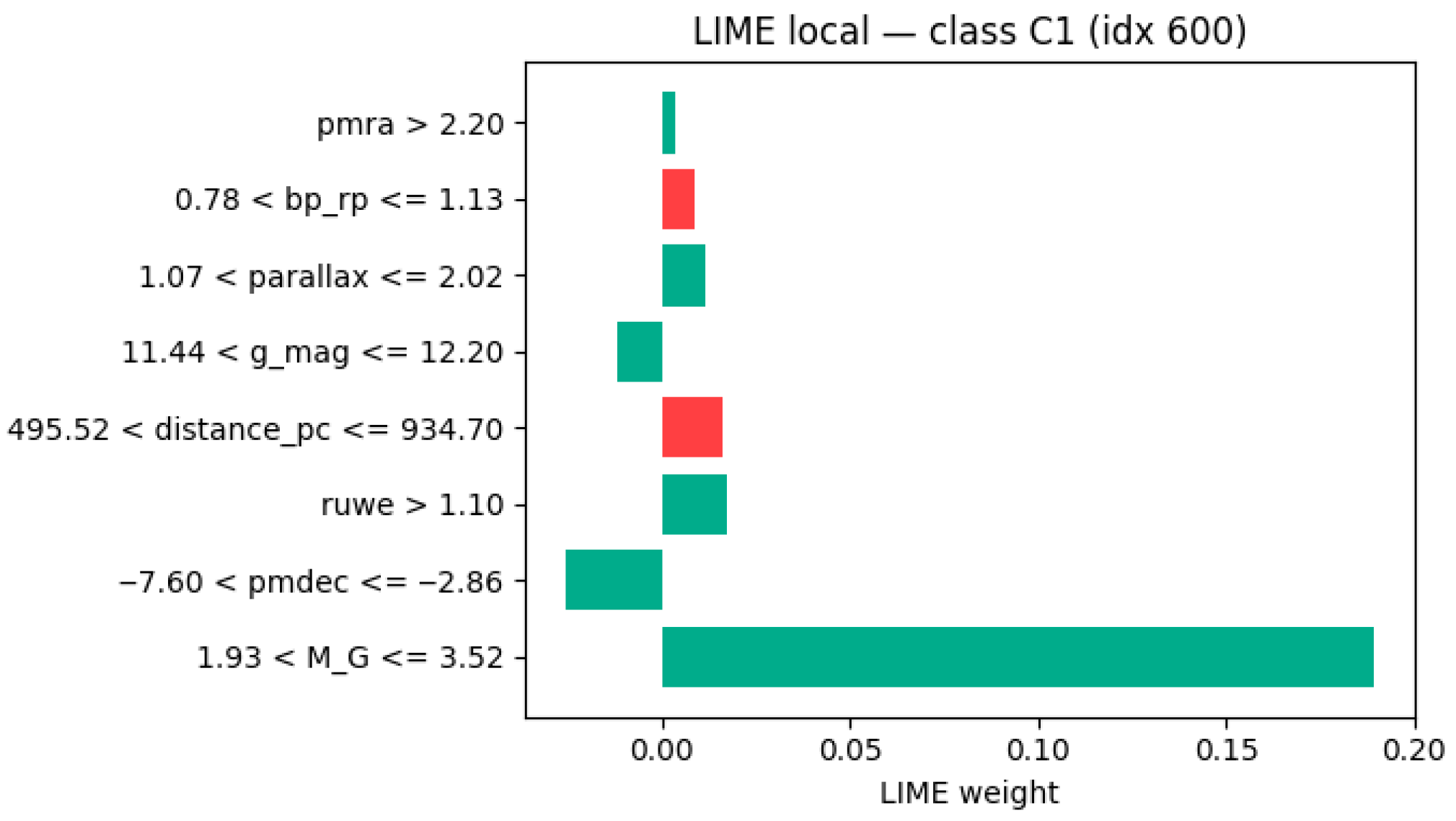

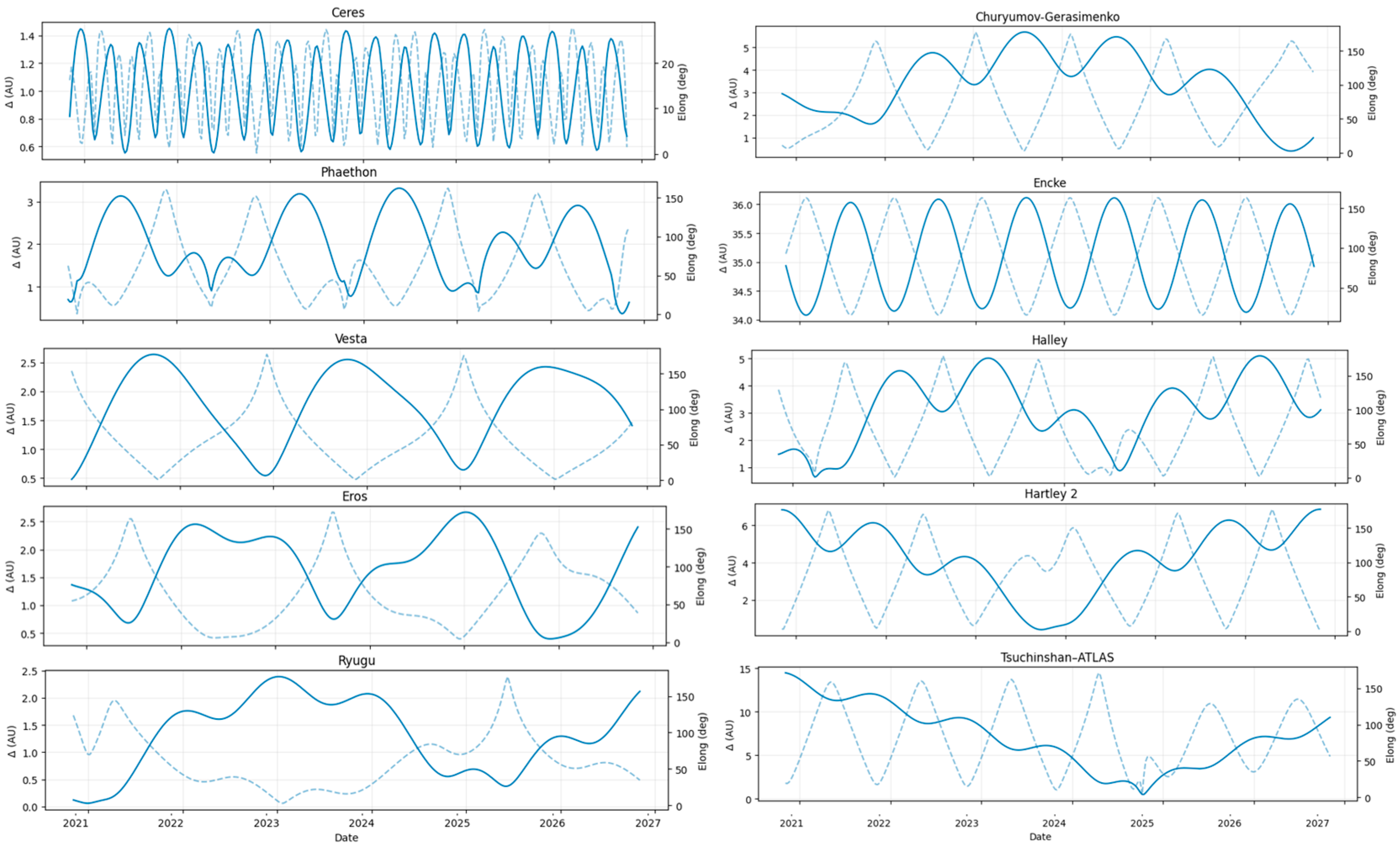

4.1.1. Comets and Asteroids

4.1.2. Stellar Data—Gaia Mission

- The color index (BP_RP) shows a clear bimodal structure, with a dominant peak near 1.0 mag, corresponding to solar-type (G–K) stars, and a smaller group at BP_RP < 0.5, associated with hotter A–F type stars. This distribution reflects the prevalence of mid-temperature stars in the local Galactic neighborhood.

- The absolute magnitude (M_G) histogram spans from –5 to +10 mag, with two visible concentrations: a bright group (M_G ≈ 0) representing giants and subgiants, and a broader peak around M_G ≈ 4, corresponding to main-sequence stars. This separation anticipates the morphology observed in the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram, Figure 7.

- The distance distribution follows an exponential-like decay, concentrated below 2000 parsecs, consistent with the imposed quality filters (parallax_over_error > 5.0) that favor nearby, well-measured stars.

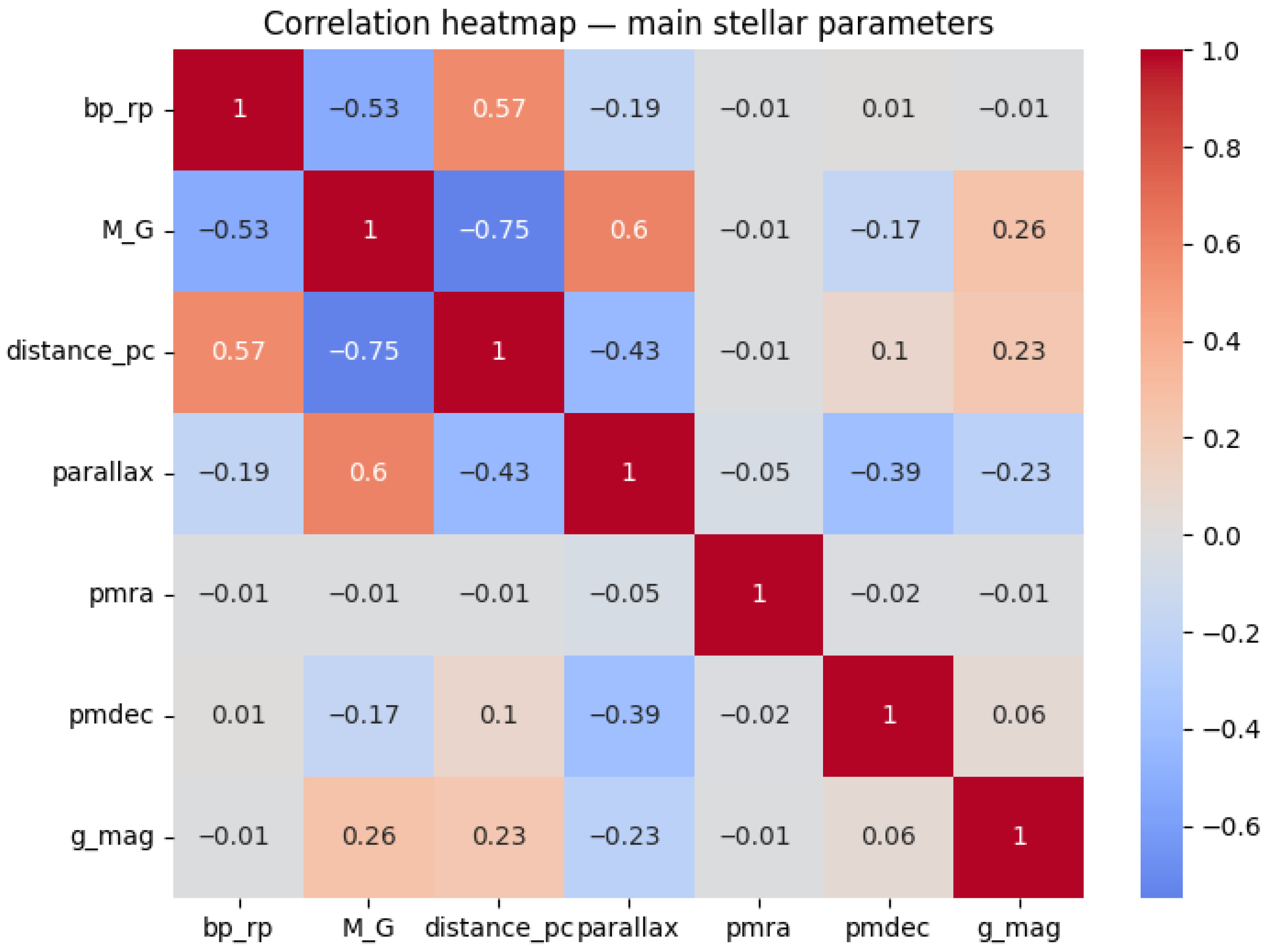

- M_G and distance show a strong negative correlation (ρ = −0.75), reflecting that distant stars tend to appear intrinsically brighter in the sample, due to the observational bias favoring luminous objects at large distances.

- M_G correlates positively with parallax (ρ = +0.6), consistent with the inverse relationship between distance and parallax.

- The color index (BP_RP) correlates moderately with M_G (ρ = −0.53) and distance (ρ = +0.57), indicating that redder, cooler stars dominate the nearby population, while bluer, hotter stars are detected farther away due to their higher intrinsic luminosity.

- Proper motion components (pmra, pmdec) show negligible correlations with the photometric and geometric variables, confirming their statistical independence for this bright-magnitude subsample.

4.2. Fuzzy—XAI

4.2.1. Fuzzy C-Means Clustering Results

- Cluster 0—Intermediate Main Sequence:

- Cluster 1—Transitional Zone (Subgiants/Late Dwarfs):

- Cluster 2—Red and Luminous Giants:

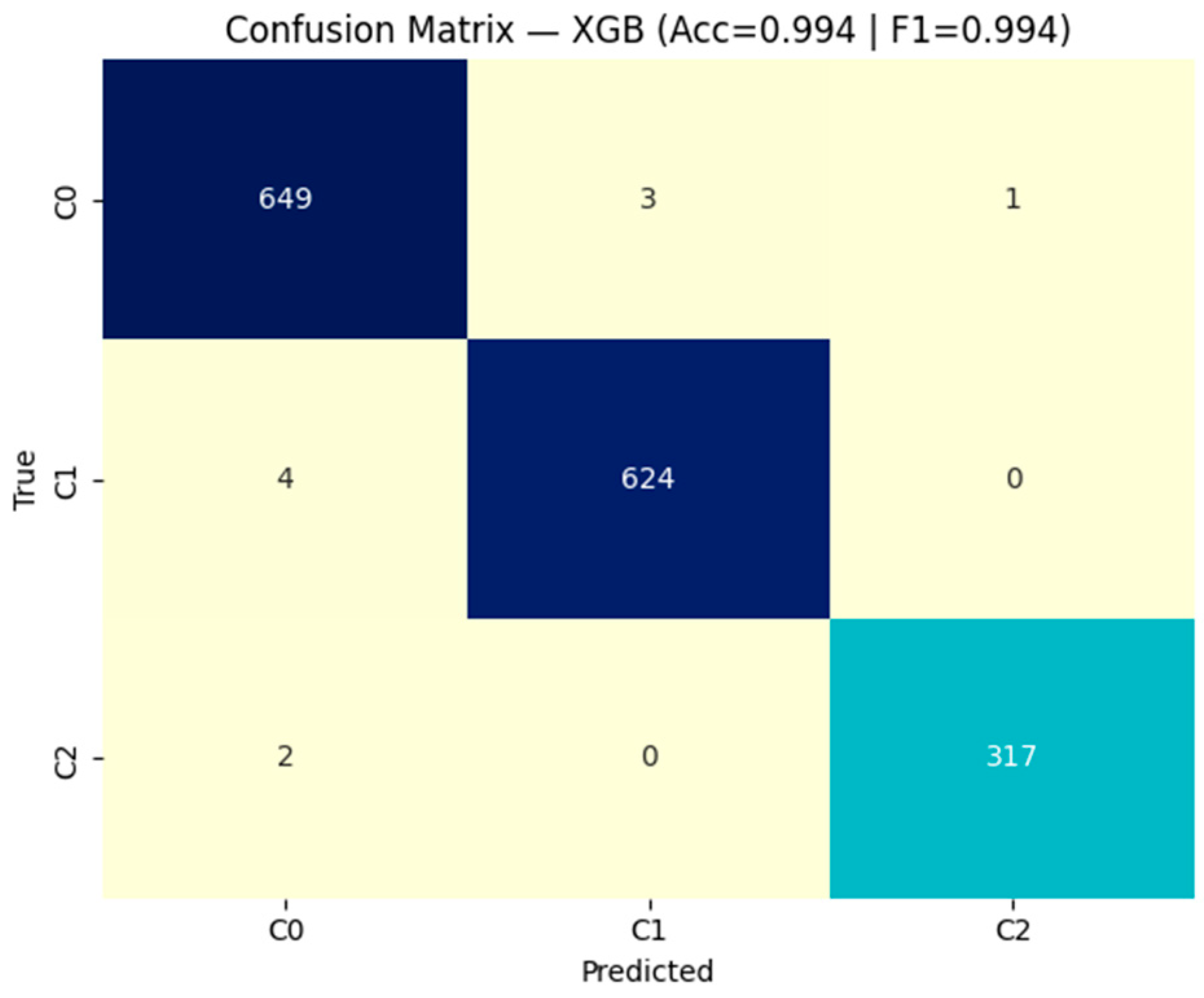

4.2.2. Predictive and Explainable Modeling

- Photometric features: bp_rp, M_G, g_mag;

- Geometric features: parallax, distance_pc, parallax_error, parallax_over_error;

- Kinematic features: pmra, pmdec;

- Quality indicator: ruwe.

- The target variables were:

- For the classifier: cluster (0 = main sequence, 1 = subgiant/transition, 2 = red giant);

- For the regressors: , , , representing the membership degrees obtained by Fuzzy C-Means.

4.2.3. Model Explainability via LIME

- Cluster C0—Subgiants/Transition Region:

- Cluster C1—Main Sequence:

- Cluster C2—Red Giants and Supergiants:

- If and ; then class ≈ C2 (giant star).

- If ; then class ≈ C1 (main sequence).

4.2.4. Integrative Interpretation of FAS-XAI Results

5. Conclusions and Future Work

5.1. Conclusions

- First, the use of open astronomical data significantly enhances student motivation and participation. Working with comets, asteroids, and stellar populations transforms abstract computational exercises into meaningful, context-rich explorations of the Universe.

- Second, the incorporation of the FAS-XAI framework, which combines fuzzy logic, predictive modeling, and interpretability, helps students to grasp the link between computational reasoning and physical principles.

5.2. Future Work

- First, by extending the analysis to astronomical imaging datasets, incorporating data from SkyView and personal observations obtained with the Seestar S50 telescope. These will enable students to perform image stacking, evaluate noise-reduction techniques, and apply fuzzy and explainable models to pattern recognition in galaxies, nebulae, and star clusters.

- Second, by contrasting AI-based enhancement methods with instrumental stacking from the Seestar S50, students will explore how explainable models can assist in noise interpretation and signal recovery from low-light astrophotography.

- Third, by integrating the FAS-XAI methodology into broader STEM curricula, the project aims to bring interpretability-driven scientific inquiry to diverse domains, demonstrating that explainable AI can serve both as a research tool and a pedagogical catalyst for curiosity-driven learning.

- Ultimately, the FAS-XAI framework can be extended far beyond astronomy. Once students have mastered the workflow, from data acquisition and fuzzy modeling to explainable interpretation, they can transfer these processes to any domain they feel most connected to.

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akeson, R. L., Chen, X., Ciardi, D., Crane, M., Good, J., Harbut, M., Jackson, E., Kane, S. R., Laity, A. C., Leifer, S., Lynn, M., McElroy, D. L., Papin, M., Plavchan, P., Ramírez, S. V., Rey, R., von Braun, K., Wittman, M., Abajian, M., … Zhang, A. (2013). The NASA exoplanet archive: Data and tools for exoplanet research. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 125(930), 989–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra, V., Delouille, V., Kretzschmar, M., & Hochedez, J. F. (2009). Fast and robust segmentation of solar EUV images: Algorithm and results for solar cycle 23. Astronomy and Astrophysics, 505(1), 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuto, F., Piana, M., Campi, C., & Massone, A. M. (2018). A hybrid supervised/unsupervised machine learning approach to solar flare prediction. The Astrophysical Journal, 853(1), 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxner, S. R., Impey, C. D., Romine, J., & Nieberding, M. (2018). Linking introductory astronomy students’ basic science knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, sources of information, and information literacy. Physical Review Physics Education Research, 14(1), 010142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colazo, M., Alvarez-Candal, A., & Duffard, R. (2022). Zero-phase angle asteroid taxonomy classification using unsupervised machine learning algorithms. Astronomy and Astrophysics, 666, A77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, I. A., Morais, C., Aguiar, T., & Silva, A. (2025). Democratizing Astronomy through teacher training in Portuguese-speaking contexts. Open Astronomy, 34(1), 20250019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domenech-Casal, J., & Ruiz-Espana, N. (2017). Mission to Stars: A Science and Technology educational project on astronomy, spatial missions and scientific research. Revista Eureka Sobre Enseñanza y Divulgación de las Ciencias, 14(1), 98–114. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, M., da Fonseca, M. O., Batista, M. C., da Silva Filho, O. L., & Strapasson, A. (2025). Greek Astromythology: Intersections between mythology history and modern astronomy education. Frontiers in Education, 10, 1431336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsburg, A., Sipőcz, B. M., Brasseur, C. E., Cowperthwaite, P. S., Craig, M. W., Deil, C., Guillochon, J., Guzman, G., Liedtke, S., Lim, P. L., Lockhart, K. E., Mommert, M., Morris, B. M., Norman, H., Parikh, M., Persson, M. V., Robitaille, T. P., Segovia, J.-C., Singer, L. P., … Woillez, J. (2019). Astroquery: An astronomical web-querying package in Python. The Astronomical Journal, 157(3), 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgini, J. D., Yeomans, D. K., Chamberlin, A. B., Chodas, P. W., Jacobson, R. A., Keesey, M. S., Lieske, J. H., Ostro, S. J., Standish, E. M., & Wimberly, R. N. (1996). JPL’s on-line solar system data service. Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society, 28, 1158. [Google Scholar]

- Huerta-Cancino, L., & Ale-Silva, J. (2024). Augmented astronomy for science teaching and learning. In J. Wei, & G. Margetis (Eds.), Human-centered design, operation and evaluation of mobile communications, Pt I, mobile 2024 (Vol. 14737, pp. 235–253). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpouzis, K. (2024). Explainable AI for intelligent tutoring systems (pp. 59–70). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, H., Shum, S. B., Chen, G., Conati, C., Tsai, Y. S., Kay, J., Knight, S., Martinez-Maldonado, R., Sadiq, S., & Gašević, D. (2022). Explainable artificial intelligence in education. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 3(May), 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajcik, J. S., & Blumenfeld, P. C. (2005). Project-based learning. In R. K. Sawyer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 317–334). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Langer, N., & Kudritzki, R. P. (2014). The spectroscopic Hertzsprung-Russell diagram. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 564, A52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. M. (2017). Astronomy education awards in the IUSE:EHR portfolio. Physics Teacher, 55(1), 58–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. C., Huang, A. Y. Q., & Lu, O. H. T. (2023). Artificial intelligence in intelligent tutoring systems toward sustainable education: A systematic review. Smart Learning Environments, 10(1), 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Shen, Y. P., Song, H. Q., Yan, F. B., & Su, Y. R. (2024). Solar radio spectrogram segmentation algorithm based on improved fuzzy C-means clustering and adaptive cross filtering. Physica Scripta, 99(4), 45005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín Díaz, G. (2025a). Fuzzy C-means and explainable AI for quantum entanglement classification and noise analysis. Mathematics, 13, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín Díaz, G. (2025b). Supporting reflective AI use in education: A fuzzy-explainable model for identifying cognitive risk profiles. Education Sciences, 15(7), 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín Díaz, G., Gómez Medina, R., & Aijón Jiménez, J. A. (2024). Integrating fuzzy C-means clustering and explainable AI for robust galaxy classification. Mathematics, 12(18), 2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín Díaz, G., Gómez Medina, R., & Aijón Jiménez, J. A. (2025). A methodological framework for business decisions with explainable AI and the analytic hierarchical process. Processes, 13(1), 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minor Planet Center (MPC). (2024). MPC database of comets and minor planets. Available online: https://minorplanetcenter.net/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Molnar, C. (2019). Interpretable machine learning. In A guide for making black box models explainable (Book, 247). Lean Publishing. Available online: https://christophm.github.io/interpretable-ml-book (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Offner, S. S. R., Taylor, J., Markey, C., Chen, H. H. H., Pineda, J. E., Goodman, A. A., Burkert, A., Ginsburg, A., & Choudhury, S. (2022). Turbulence, coherence, and collapse: Three phases for core evolution. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 517(1), 885–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L., Meneses, A., Montenegro, M., & Cortes, C. (2025). Direct and indirect opportunities to learn astronomy within the chilean science curriculum. International Journal of Science an Mathematics Education, 23(1), 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafique, U., & Qaiser, H. (2014). A comparative study of data mining process models (KDD, CRISP-DM and SEMMA). International Journal of Innovation and Scientific Research, 12(1), 217–222. Available online: http://www.ijisr.issr-journals.org/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Sugeno, M., & Yasukawa, T. (1993). A fuzzy-logic-based approach to qualitative modeling. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems, 1(1), 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, J. J., Andersen, K., Arculli, T., Browning, O., Ding, J., Edwards, N., Fanning, T., Geyer, J., Huber, G., Jin-Ngo, D., Kelliher, B., Kirkpatrick, C., Kirkpatrick, L., Klink, D., Lavine, C., Lawrence, G., Lawrence, Y., Cyrus Leung, F. L., Luebbers, J., … Hedrick, R. (2022). The renovated thacher observatory and first science results. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 134(1033), 035005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, G. M., Kálmán, S., Borsato, L., Hegedus, V., Mészáros, S., & Szabó, R. (2023). Sub-Jovian desert of exoplanets at its boundaries: Parameter dependence along the main sequence. Astronomy and Astrophysics, 671, A132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh-Popp, M., Kim, J. W., Lemson, G., Medvedev, D., Raddick, M. J., Szalay, A. S., Thakar, A. R., Booker, J., Chhetri, C., Dobos, L., & Rippin, M. (2020). SciServer: A science platform for astronomy and beyond. Astronomy and Computing, 33, 100412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanga, P., Pauwels, T., Mignard, F., Muinonen, K., Cellino, A., David, P., Hestro, D., Spoto, F., & Berthier, J. (2023). Astrophysics special issue gaia data release 3 the solar system survey. Astronomy and Astrophysics, 12, A12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzpen, B., Houseal, A. K., Slater, T. F., & Nuhfer, E. B. (2019). Scientific and quantitative literacy: A comparative study between STEM and non-STEM undergraduates taking physics. European Journal of Physics, 40(3), 035701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Description | Units |

|---|---|---|

| date | Observation epoch (UTC) | ISO format |

| x, y, z | Heliocentric coordinates | AU |

| r_au | Heliocentric distance () | AU |

| delta_au | Geocentric distance | AU |

| elong_deg | Solar elongation (Sun–Earth–object angle) | degrees |

| speed_au_d | Apparent heliocentric velocity | AU/day |

| lambda_deg | Ecliptic longitude | degrees |

| beta_deg | Ecliptic latitude | degrees |

| Variable | Type | Units | Description | Physical/Educational Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| source_id | Identifier | — | Unique Gaia DR3 identifier of each star. | Used for data traceability (non-analytical). |

| ra | Positional | degrees (°) | Right Ascension: horizontal coordinate in the equatorial system (celestial longitude). | Locates the star in the sky (0–360°). |

| dec | Positional | degrees (°) | Declination: vertical coordinate in the equatorial system (celestial latitude). | Together with ra, defines the star’s position on the celestial sphere. |

| parallax | Geometric | milliarcseconds (mas) | Trigonometric parallax: apparent displacement due to Earth’s orbital motion. | Inversely proportional to distance. Distance (pc) ≈ 1000/parallax (mas). |

| parallax_error | Geometric | mas | Standard uncertainty of parallax measurement. | Used as a quality indicator for distance_pc. |

| parallax_over_error | Dimensionless | — | Signal-to-noise ratio of the parallax. | Indicates measurement reliability; values >5 imply high accuracy. |

| pmra, pmdec | Kinematic | mas yr−1 | Proper motion components in right ascension and declination. | Quantify the star’s apparent motion across the sky due to real spatial velocity. |

| ruwe | Quality | — | Renormalized Unit Weight Error: statistical indicator of astrometric fit quality. | RUWE ≈ 1—good fit; RUWE > 1.6—possible binarity or systematic errors. |

| g_mag | Photometric | magnitudes | Integrated magnitude in the Gaia G (white light) band. | Represents total brightness; lower values indicate higher luminosity. |

| bp_mag, rp_mag | Photometric | magnitudes | Magnitudes in the blue (BP) and red (RP) bands. | It is used to compute the stellar color index (bp_rp), related to temperature. |

| bp_rp | Derived (Color) | magnitudes | Color index is defined as BP_ RP. | Photometric color: direct indicator of effective temperature (cool stars—redder, hot stars—bluer). |

| distance_pc | Derived (Geometric) | parsecs (pc) | Estimated distance from the Sun, derived from parallax. | Converts apparent brightness to intrinsic luminosity. |

| M_G | Derived (Luminosity) | absolute magnitudes | Absolute magnitude in the G band, corrected for distance modulus. | Reflects intrinsic stellar power; plotted against bp_rp in the HR diagram. |

| random_index | Technical | — | Gaia random index used for sampling. | No physical meaning; ensures reproducibility. |

| Cluster | Source_id | bp_rp | M_G | g_mag | Distance_pc | Parallax | pmra | pmdec | ruwe | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 267581781428301 | 1.2650 | 1.407 | 12.63 | 1756 | 0.56946 | −5.8592 | 3.908 | 1.0073 | 0.999380 | 0.000239 | 0.000381 | 0.999380 |

| 0 | 611459980378139 | 1.2128 | 13.589 | 12.652 | 1813.6 | 0.5514 | −21.187 | 8.1636 | 0.97565 | 0.999310 | 0.000257 | 0.000433 | 0.999310 |

| 0 | 397499133909490 | 1.2451 | 13.624 | 10.313 | 616.86 | 1.6211 | −35.69 | −3.0069 | 0.92931 | 0.999300 | 0.000256 | 0.000444 | 0.999300 |

| 0 | 349367820418688 | 1.2143 | 13.575 | 12.76 | 1907.7 | 0.5242 | −7.1835 | 0.50699 | 1.1093 | 0.999280 | 0.000268 | 0.000452 | 0.999280 |

| 1 | 455360710412683 | 0.8956 | 4.0592 | 11.242 | 273.19 | 3.6605 | −26.73 | −9.237 | 1.3457 | 0.000120 | 0.999850 | 0.000030 | 0.999850 |

| 1 | 438964284495378 | 0.8754 | 4.0697 | 12.839 | 567.32 | 1.7627 | 5.977 | −10.865 | 0.96552 | 0.000130 | 0.999829 | 0.000041 | 0.999829 |

| 1 | 446865467824336 | 0.8497 | 4.0215 | 11.58 | 324.8 | 3.0788 | −4.6838 | −5.0712 | 0.74249 | 0.000140 | 0.999820 | 0.000040 | 0.999820 |

| 1 | 632484518742924 | 0.8463 | 4.055 | 12.042 | 395.82 | 2.5264 | −6.4286 | −1.596 | 1.1458 | 0.000160 | 0.999790 | 0.000050 | 0.999790 |

| 2 | 524151857697601 | 1.9216 | −0.61984 | 12.276 | 3795.5 | 0.26347 | −5.1328 | 2.4405 | 0.89483 | 0.000530 | 0.000106 | 0.999364 | 0.999364 |

| 2 | 533562039136869 | 1.9951 | −0.5636 | 11.313 | 2372.8 | 0.42144 | 1.353 | −2.3059 | 1.0184 | 0.000540 | 0.000107 | 0.999353 | 0.999353 |

| 2 | 531918010690120 | 2.0026 | −0.57335 | 12.078 | 3391 | 0.2949 | −1.0219 | 4.4415 | 1.0145 | 0.000660 | 0.000131 | 0.999209 | 0.999209 |

| 2 | 534731396375339 | 1.888 | −0.57185 | 12.574 | 4257.9 | 0.23486 | −5.526 | 3.8552 | 0.97037 | 0.000850 | 0.000166 | 0.998984 | 0.998984 |

| Target | R2 | RMSE | Corr |

|---|---|---|---|

| μ0 | 0.999 | 0.011 | 1.000 |

| μ1 | 0.999 | 0.009 | 1.000 |

| μ2 | 0.999 | 0.010 | 1.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marín Díaz, G. Integrating Exploratory Data Analysis and Explainable AI into Astronomy Education: A Fuzzy Approach to Data-Literate Learning. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1688. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121688

Marín Díaz G. Integrating Exploratory Data Analysis and Explainable AI into Astronomy Education: A Fuzzy Approach to Data-Literate Learning. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1688. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121688

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarín Díaz, Gabriel. 2025. "Integrating Exploratory Data Analysis and Explainable AI into Astronomy Education: A Fuzzy Approach to Data-Literate Learning" Education Sciences 15, no. 12: 1688. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121688

APA StyleMarín Díaz, G. (2025). Integrating Exploratory Data Analysis and Explainable AI into Astronomy Education: A Fuzzy Approach to Data-Literate Learning. Education Sciences, 15(12), 1688. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121688