Self-Rated Originality as a Mediator That Connects Creative Activities and AI-Rated Originality in Divergent Thinking

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Paradox and Balance in Creativity

1.2. Tensions in Creativity Assessments

1.3. Alignment Between Self- and Others-Rated Originality: The Role of Engaging in Everyday Creative Activities

1.4. Goal of the Current Study

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Divergent Thinking Tasks (DT Tasks)

Alternative Uses Task (AUT)

Reversed Alternative Uses Task (rAUT)

2.2.2. Self-Ratings of DT Responses

2.2.3. AI Scoring of DT Responses

2.2.4. Self-Reported Creative Activities

2.3. Data Collection Procedures

2.4. Data Analysis Overview

3. Results

3.1. Bivariate Correlations

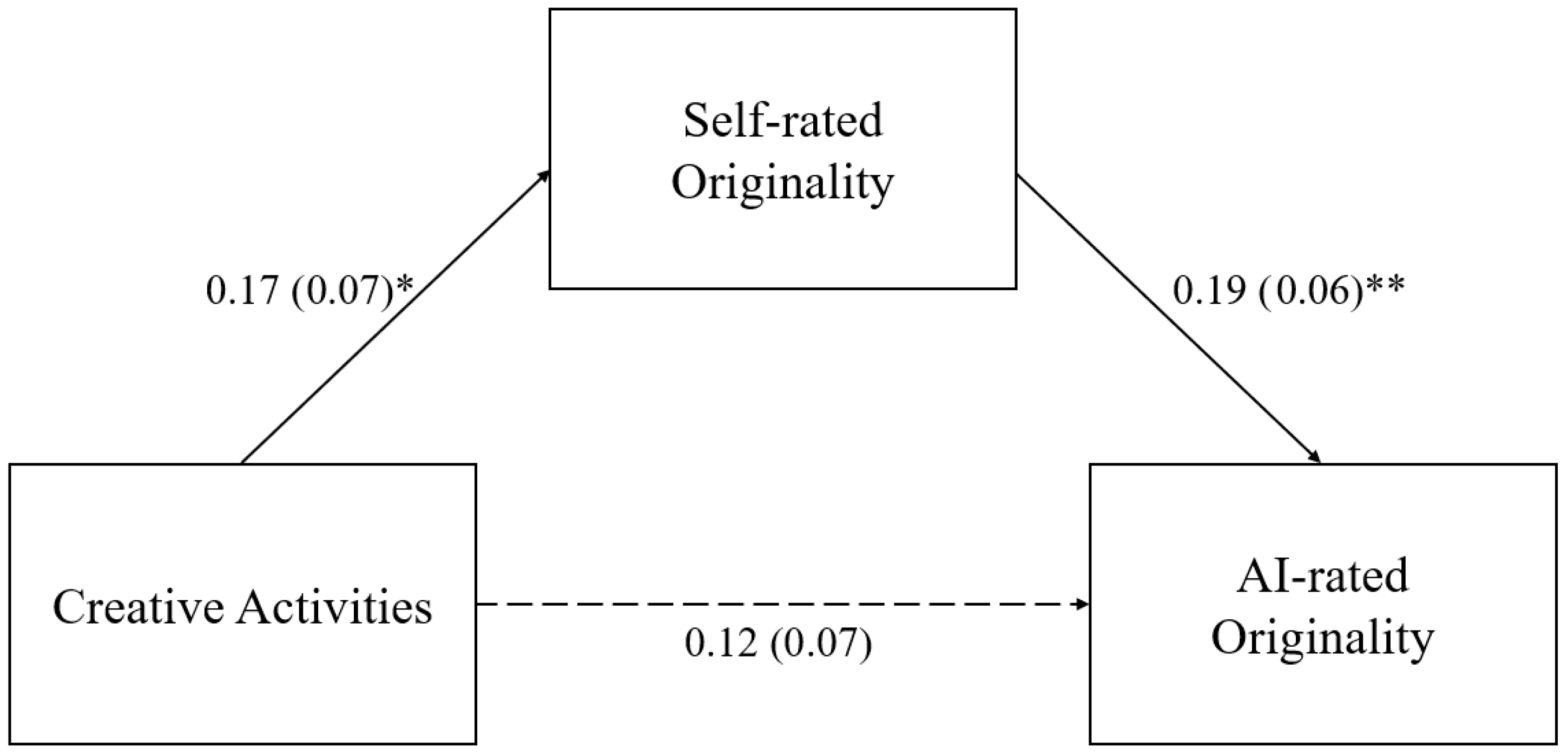

3.2. Testing a Mediation Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

4.1.1. Engaging in Creative Activities Did Not Directly Enhance AI-Rated Originality

4.1.2. Self-Rated Originality Was a Mediator That Connected Everyday Creative Activities and AI-Rated Originality

4.2. Limitations and Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acar, S., Dumas, D., Organisciak, P., & Berthiaume, K. (2024). Measuring original thinking in elementary school: Development and validation of a computational psychometric approach. Journal of Educational Psychology, 116(6), 953–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, P. A. (2013). Calibration: What is it and why it matters? An introduction to the special issue on calibrating calibration. Learning and Instruction, 24, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T. M. (1979). Effects of external evaluation on artistic creativity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(2), 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T. M. (1982). Social psychology of creativity: A consensual assessment technique. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43(5), 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T. M., Goldfarb, P., & Brackfleld, S. C. (1990). Social influences on creativity: Evaluation, coaction, and surveillance. Creativity Research Journal, 3(1), 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbot, B., & Kaufman, J. C. (2025). PISA 2022 creative thinking assessment: Opportunities, challenges, and cautions. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 59(1), e70003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batey, M., Furnham, A., & Safiullina, X. (2010). Intelligence, general knowledge, and personality as predictors of creativity. Learning and Individual Differences, 20, 532–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beghetto, R. A. (2021). There is no creativity without uncertainty: Dubito Ergo Creo. Journal of Creativity, 31, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beghetto, R. A., & Kaufman, J. C. (2007). Toward a broader conception of creativity: A case for mini-c creativity. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 1, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beghetto, R. A., & Kaufman, J. C. (2014). Classroom contexts for creativity. High Ability Studies, 25, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, M. (1995). Creativity and unpredictability. Stanford Humanities Review, 4(2), 123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Brillenburg Wurth, K. (2019). The creativity paradox: An introductory essay. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 53(2), 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, H. L., Lien, Y. C., Lin, A. P., & Chuang, Y. T. (2022). How followership boosts creative performance as mediated by work autonomy and creative self-efficacy in higher education administrative jobs. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 853311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diedrich, J., Jauk, E., Silvia, P. J., Gredlein, J. M., Neubauer, A. C., & Benedek, M. (2018). Assessment of real-life creativity: The inventory of creative activities and achievements (ICAA). Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 12(3), 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, A. (2015). How creativity happens in the brain. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- DiStefano, P. V., Patterson, J. D., & Beaty, R. (2023). Automatic scoring of metaphor creativity with large language models. PsyArXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, D., Acar, S., Berthiaume, K., Organisciak, P., Eby, D., Grajzel, K., Vlaamster, T., Newman, M., & Carrera, M. (2023). What makes children’s responses to creativity assessments difficult to judge reliably? The Journal of Creative Behavior, 57(3), 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, D., & Kaufman, J. C. (2024). Evaluation is creation: Self and social judgments of creativity across the Four-C model. Educational Psychology Review, 36(4), 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, D., Kim, Y., Carrera-Flores, M., Kagan, S., Acar, S., & Organisciak, P. (2025). Understanding elementary students’ creativity as a trade-off between originality and task appropriateness: A Pareto optimization study. Journal of Educational Psychology. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, D., Johnson, K., Ehrlinger, J., & Kruger, J. (2003). Why people fail to recognize their own incompetence. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(3), 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glăveanu, V. P. (2015). Creativity as a sociocultural act. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 49(3), 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalo, J. A., Flynn, F. J., & Kim, S. H. (2010). Are two narcissists better than one? The link between narcissism, perceived creativity, and creative performance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(11), 1484–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilford, J. P. (1967). The nature of human intelligence. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond baron and kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76(4), 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hennessey, B. A. (2010). The creativity-motivation connection. The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity, 2010, 342–365. [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro, C., Sato, Y., Takahashi, A., Abe, Y., Kato, E., & Takagishi, H. (2022). Relationships among creativity indices: Creative potential, production, achievement, and beliefs about own creative personality. PLoS ONE, 17(9), e0273303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, S., & Dumas, D. (2025). More creative activities, lower creative ability: Exploring an unexpected PISA finding. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 59(2), e70035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwowski, M., Lebuda, I., & Wiśniewska, E. (2018). Measuring creative self-efficacy and creative personal identity. The International Journal of Creativity & Problem Solving, 28(1), 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, J. C. (2023). The creativity advantage. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, J. C., & Beghetto, R. A. (2009). Beyond big and little: The four c model of creativity. Review of General Psychology, 13(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J. C., Beghetto, R. A., & Watson, C. (2016). Creative metacognition and self-ratings of creative performance: A 4-C perspective. Learning and Individual Differences, 51, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J. C., Evans, M. L., & Baer, J. (2010). The American idol effect: Are students good judges of their creativity across domains? Empirical studies of the arts, 28(1), 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lebuda, I., Hofer, G., & Benedek, M. (2025). Determinants of creative metacognitive monitoring: Creativity, personality, and task-related predictors of self-assessed ideas and creative performance. Metacognition and Learning, 20(1), 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebuda, I., Hofer, G., Rominger, C., & Benedek, M. (2024). No strong support for a Dunning–Kruger effect in creativity: Analyses of self-assessment in absolute and relative terms. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 11883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J., Day, J. D., Meara, N. M., & Maxwell, S. E. (2002). Discrimination of social knowledge and its flexible application from creativity: A multitrait-multimethod approach. Personality and Individual Differences, 32, 913–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, S., Fischhoff, B., & Phillips, L. D. (1982). Calibration of probabilities: The state of the art to 1980. In D. Kahneman, P. Slovic, & A. Tversky (Eds.), Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases (pp. 306–334). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Persem, A., Moreno-Rodriguez, S., Ovando-Tellez, M., Bieth, T., Guiet, S., Brochard, J., & Volle, E. (2024). How subjective idea valuation energizes and guides creative idea generation. American Psychologist, 79(3), 403–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luchini, S. A., Maliakkal, N. T., DiStefano, P. V., Laverghetta, A., Jr., Patterson, J. D., Beaty, R. E., & Reiter-Palmon, R. (2025). Automated scoring of creative problem solving with large language models: A comparison of originality and quality ratings. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutter, Y., & Hübner, R. (2024). The effect of expertise on the creation and evaluation of visual compositions in terms of creativity and beauty. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 13675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, T. O., & Narens, L. (1990). Metamemory: A theoretical framework and some new findings. In G. H. Bower (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 26, pp. 125–173). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, T. O., & Narens, L. (1994). Why investigate metacognition? In J. Metcalfe, & A. P. Shimamura (Eds.), Metacognition: Knowing about knowing (pp. 1–25). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2024a). PISA 2022 results (Volume III): Creative minds, creative schools. PISA; OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2024b). PISA 2022 technical report. PISA; OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisciak, P., Acar, S., Dumas, D., & Berthiaume, K. (2023). Beyond semantic distance: Automated scoring of divergent thinking greatly improves with large language models. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 49, 101356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisciak, P., Dumas, D., Acar, S., & de Chantal, P. L. (2024). Open creativity scoring [computer software]. University of Denver. Available online: https://openscoring.du.edu (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Ostermaier, A., & Uhl, M. (2020). Performance evaluation and creativity: Balancing originality and usefulness. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 86, 101552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M., Lee, J., & Hahn, D. W. (2002, August 22–25). Self-reported creativity, creativity, and intelligence. Poster presented at the American Psychological Association, Chicago, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Pretz, J. E., & McCollum, V. A. (2014). Self-perceptions of creativity do not always reflect actual creative performance. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 8(2), 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runco, M. A., & Jaeger, G. J. (2012). The standard definition of creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 24(1), 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, R. K. (2021). The iterative and improvisational nature of the creative process. Journal of Creativity, 31, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherbakova, A., Dumas, D., Acar, S., Berthiaume, K., & Organisciak, P. (2024). Performance and perception of creativity and academic achievement in elementary school students: A normal mixture modeling study. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 58(2), 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherbakova, A., Dumas, D., Kagan, S., Vlaamster, T., Acar, S., & Organisciak, P. (2025). Reversing the alternate uses task. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 2025, 101915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraw, G., & Moshman, D. (1995). Metacognitive theories. Educational Psychology Review 7, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, P. J. (2008). Discernment and creativity: How well can people identify their most creative ideas? Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 2, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, P. J., Beaty, R. E., Nusbaum, E. C., Eddington, K. M., Levin-Aspenson, H., & Kwapil, T. R. (2014). Everyday creativity in daily life: An experience-sampling study of “little c” creativity. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 8(2), 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, P. J., Nusbaum, E. C., & Beaty, R. E. (2017). Old or new? Evaluating the old/new scoring method for divergent thinking tasks. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 51(3), 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, P. J., & Phillips, A. G. (2004). Self-awareness, self-evaluation, and creativity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(8), 1009–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, P. J., Wigert, B., Reiter-Palmon, R., & Kaufman, J. C. (2012). Assessing creativity with self-report scales: A review and empirical evaluation. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 6(1), 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonton, D. K. (2018). Defining creativity: Don’t we also need to define what is not creative? The Journal of Creative Behavior, 52(1), 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonton, D. K. (2019). Creativity in sociocultural systems. In The oxford handbook of group creativity and innovation. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sosa, R., & Gero, J. S. (2004). Diffusion of creative design: Gatekeeping effects. International Journal of Architectural Computing, 2(4), 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, L. M., Hardy, J. H., III, Day, E. A., Watts, L. L., & Mumford, M. D. (2021). Navigating creative paradoxes: Exploration and exploitation effort drive novelty and usefulness. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 15(1), 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M. I. (1953). Creativity and culture. The Journal of Psychology, 36(2), 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, K., & Urban, M. (2025). Metacognition and motivation in creativity: Examining the roles of self-efficacy and values as cues for metacognitive judgments. Metacognition and Learning, 20(1), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, M., & Urban, K. (2021). Unskilled but aware of it? Cluster analysis of creative metacognition from preschool age to early adulthood. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 55(4), 937–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Xiao, H., Yin, H., Wei, J., Li, S., & Shi, B. (2025). The different relationships between mobile phone dependence and adolescents’ scientific and artistic creativity: Self-esteem and creative identity as mediators. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 59(2), e70024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, S., Jaggy, A. K., & Goecke, B. (2025). Introducing the inventory of creative activities for young adolescents: An adaption and validation study. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 57, 101836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | Min | Max | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. AUT Originality (AI-rated) | 2.60 | 0.38 | 1.40 | 3.31 | −1.00 | 0.69 |

| 2. rAUT Originality (AI-rated) | 2.31 | 0.31 | 1.38 | 3.17 | −0.60 | 0.32 |

| 3. DT Originality (AI-rated) | 4.91 | 0.63 | 2.99 | 6.03 | −0.87 | 0.44 |

| 4. AUT Originality (self-rated) | 2.48 | 0.74 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 0.46 | 0.29 |

| 5. rAUT Originality (self-rated) | 2.55 | 0.63 | 1.00 | 4.57 | 0.35 | 0.34 |

| 6. DT Originality (self-rated) | 5.03 | 1.29 | 4.97 | 4.98 | 0.48 | 0.51 |

| 7. Literature Activities | 14.97 | 4.56 | 0.00 | 30.00 | 0.06 | 0.31 |

| 8. Music Activities | 13.37 | 6.73 | 0.00 | 30.00 | 0.79 | 0.46 |

| 9. Arts-and-Crafts Activities | 20.58 | 6.23 | 0.00 | 30.00 | −0.42 | 0.42 |

| 10. Creative Cooking Activities | 16.21 | 6.63 | 0.00 | 30.00 | 0.41 | 0.45 |

| 11. Sports Activities | 10.74 | 5.91 | 0.00 | 30.00 | 1.36 | 0.40 |

| 12. Visual Arts Activities | 14.68 | 5.21 | 0.00 | 30.00 | 0.42 | 0.35 |

| 13. Performing Arts Activities | 11.18 | 4.57 | 0.00 | 27.00 | 0.79 | 0.31 |

| 14. Science and Engineering Activities | 11.90 | 5.29 | 0.00 | 28.00 | 0.93 | 0.36 |

| 15. Creative Activities (Total) | 19.03 | 19.03 | 0.00 | 35.83 | 0.55 | 0.35 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-rated AUT | — | ||||||

| 2. Self-rated rAUT | 0.80 *** | — | |||||

| 3. Self-rated DT tasks | 0.35 *** | 0.32 ** | — | ||||

| 4. AI-rated AUT | 0.20 ** | 0.17 * | 0.10 | — | |||

| 5. AI-rated rAUT | 0.12 | 0.25 ** | 0.04 | 0.63 *** | — | ||

| 6. AI-rated DT tasks | 0.15 * | 0.10 | 0.21 ** | 0.52 *** | 0.40 *** | — | |

| 7. Creative Activities | −0.07 | −0.03 | 0.17 * | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.15 | — |

| Effect | β | SE | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCI | UCLI | |||

| Direct effect | ||||

| Creative Activities → Self-rated Originality | 0.171 | 0.073 | 0.018 | 0.309 |

| Self-rated Originality → AI-rated Originality | 0.191 | 0.064 | 0.061 | 0.316 |

| Creative Activities → AI-rated Originality | 0.119 | 0.065 | −0.012 | 0.243 |

| Indirect effect | ||||

| Creative Activities → Self-rated Originality → AI-rated Originality | 0.033 | 0.018 | 0.006 | 0.080 |

| Total effect | ||||

| Creative Activities → Self-rated Originality → AI-rated Originality | 0.151 | 0.065 | 0.020 | 0.275 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, Y.; Dumas, D. Self-Rated Originality as a Mediator That Connects Creative Activities and AI-Rated Originality in Divergent Thinking. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1525. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111525

Kim Y, Dumas D. Self-Rated Originality as a Mediator That Connects Creative Activities and AI-Rated Originality in Divergent Thinking. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1525. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111525

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Yoojoong, and Denis Dumas. 2025. "Self-Rated Originality as a Mediator That Connects Creative Activities and AI-Rated Originality in Divergent Thinking" Education Sciences 15, no. 11: 1525. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111525

APA StyleKim, Y., & Dumas, D. (2025). Self-Rated Originality as a Mediator That Connects Creative Activities and AI-Rated Originality in Divergent Thinking. Education Sciences, 15(11), 1525. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111525