The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research: Application to Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

Local success is possible, but system change is unlikely (Fullan, 1998).Teachers fail to make the effort, or their commitment to making a difference turns to despair in the face of overload and political alienation. Agencies like school districts, teacher unions, universities either become part of the problem or fail to help.(p. 4)

Fraught with concerns, Wiggins and McTighe (2005) deftly described the result of the standardized testing fervor as “teach, test and hope for the best” (p. 3). Nevertheless, the testing and ranking of schools is an easy-to-consume political tool for governments. However, as Moir (2018) clarifies, “for any intervention to be successfully embedded, socioeconomic and cultural environments need to be acknowledged, because their variables impact on implementation success” (p. 3). In the process, the teachers, on-the-ground changemakers, become demoralized, feeling unsupported at best and silenced at worst. Their voices, and experiential knowledge about how students learn, do not appear to matter. A test score or graduation rate cannot measure the success of every educational intervention. Schools are people-places with students and teachers working together to grow and learn (Dewey, 1922; Greene, 1995; Hooks, 1994).Rarely does a day go by when the media does not feature an article about standards, standardized testing, and levels of student achievement in public schools. Establishing and raising standards, and measuring the attainment of those standards, are intended to encourage excellence in our schools.(p. 54)

Research Questions

2. Educational Reforms and Accountability

More than 600,000 students from 79 countries took the 2018 PISA test; in 2022, 81 countries participated (OECD, 2023). Such is the handwringing and fretting over the state of education that the general focus in the Canadian press was negative following the release of the 2018 PISA, even though Canada ranked fourth in reading, sixth in science and tenth in math. Subsequently, negative spins on the results calling for further educational reform dominated headlines (e.g., Goldstein, 2022). Results from the 2022 test found Canada to be the top-performing English-speaking country in math and science and second in reading. The Canadian Broadcasting Company (CBC) posted this headline on their website following the release of the PISA scores: “Canadian students’ math, reading scores have dropped since 2018—but study says it’s not all COVID’s fault” (CBC, 2023). Test scores aside, what the media did not acknowledge was that “Education systems in Canada, Denmark, Finland, Hong Kong (China), Ireland, Japan, Korea, Latvia, Macao (China) and the United Kingdom are highly equitable by PISA’s standard (combining high levels of inclusion and fairness)” (OECD, 2023, p. 27). The differential in scores between the highest-performing Canadian students and the lowest is among the smallest, indicating a well-functioning, inclusive education system.a triennial survey of 15-year-old students around the world that assesses the extent to which they have acquired key knowledge and skills essential for full participation in social and economic life. PISA assessments do not just ascertain whether students near the end of their compulsory education can reproduce what they have learned; they also examine how well students can extrapolate from what they have learned and apply their knowledge in unfamiliar settings, both in and outside of school.

3. Implementation Science

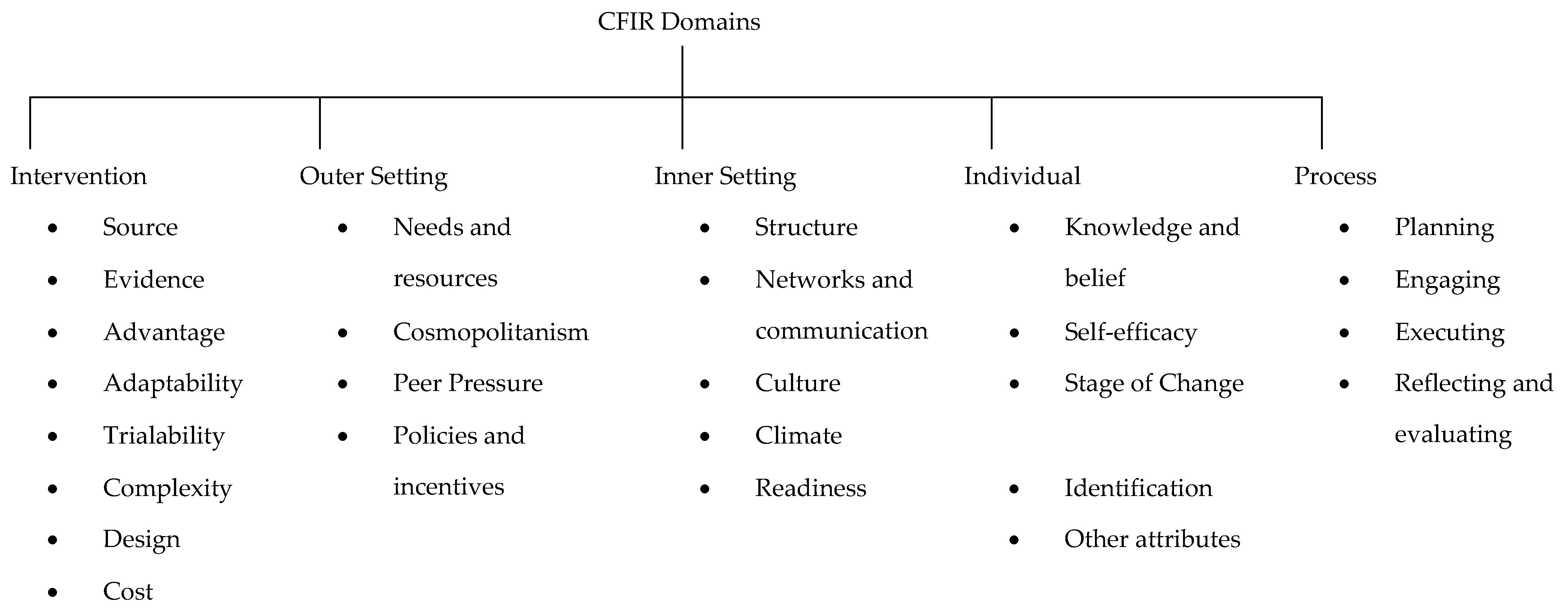

- Intervention characteristics—the features of an intervention (educational initiative or policy) that might influence implementation, including the quality of the intervention (PBMIS instruction), and how the intervention is perceived by the stakeholders (PSTs).

- Outer setting—encompasses the aspects of the external context or environment that could impact implementation (e.g., the school and school system in which the PST completes their practicum, the pedagogy of the associate teacher, and the influence of external organizations such as PHE Canada and TAPHE at the practicum site).

- Inner setting—the characteristics of the implementing organization that could influence implementation (e.g., the structural, political, and cultural contexts of the school, including the relative value of PE within the school (e.g., isolation, marginalization) the PE department/associate teacher and their practices).

- Individual—the attributes and characteristics of the individuals engaged in the implementation that might influence the intervention (e.g., PSTs’ self-efficacy, competence and confidence in PETE learning/program and this pedagogy).

- Implementation process—involves strategies or tactics that could affect the intervention/implementation, such as involving relevant individuals in the implementation and utilization of the intervention, as well as reflection and evaluation by the PST.

4. Description of the PETE Intervention

- PSTs actively reflected on their past experiences of inclusion in PE. Working together, sharing their past experiences, and engaging with the literature, PSTs arrived at themes representative of the state of inclusion in PE.

- PSTs engaged in adaptive, para-sports, and non-traditional sport (e.g., bocce, wheelchair basketball, goalball) to disrupt previous conceptions of ability and disability. Before each alternative activity, PSTs investigated their experience, anticipated challenges, and potential biases or stereotypes they might encounter (e.g., gender-related perceptions of yoga and dance). Following engagement in the activities, PSTs collaboratively debriefed their experiences, considered the potential barriers to including these activities in their curriculum and how to overcome these, and critically read the relevant literature.

- PSTs studied and actively engaged in models-based practice (e.g., teaching games for understanding, cooperative learning, sports education, and teaching personal and social responsibility). PSTs experienced modeling of various instructional strategies, exploration and engagement with the supporting literature, and micro-teaching opportunities sharing their understanding of specific instructional models.

- PSTs reconceptualized their beliefs, values, and experiences, challenging and reshaping their understanding of what constitutes a fully inclusive physical education pedagogy. They critically analyzed the literature and engaged with guest speakers, individuals who live with disabilities, and practicing physical educators.

- PSTs engaged with various literature and resources, including guest speakers, to further develop their inclusive and PBMIS pedagogy. Moreover, they actively participated in meaningful dialogs with individuals who live with disabilities and practicing physical educators, acquiring direct insights and perspectives. This multifaceted approach disrupted previous conceptions of EDIA, enriched the PSTs’ theoretical knowledge, and fostered a deeper, more empathetic comprehension of the diverse needs and experiences within inclusive physical education.

- PSTs participated in teaching experiences beyond their practicum, engaging in collaborative micro-teaching sessions at local schools each term. They crafted and presented lessons employing contemporary, inclusive instructional methods. Each PST group partnered with another for a comprehensive feedback exchange. One such session occurred at a nearby Mi’kmaw school, offering PSTs teaching opportunities, feedback, and valuable insights into Mi’kmaw schools and culture.

5. Methodology and Methods

5.1. Methodology

- (i)

- Multiple data sources—video interviews, focus groups, researcher observations/field notes;

- (ii)

- Researcher triangulation providing a varied evaluation of data—researchers from three universities;

- (iii)

- Multiple theoretical perspectives—phenomenology, CFIR, video analysis;

- (iv)

- Methodological triangulation—multiple qualitative data sources.

5.2. Methods

5.2.1. Participants

5.2.2. Interviews and Focus Groups

5.2.3. Surveys

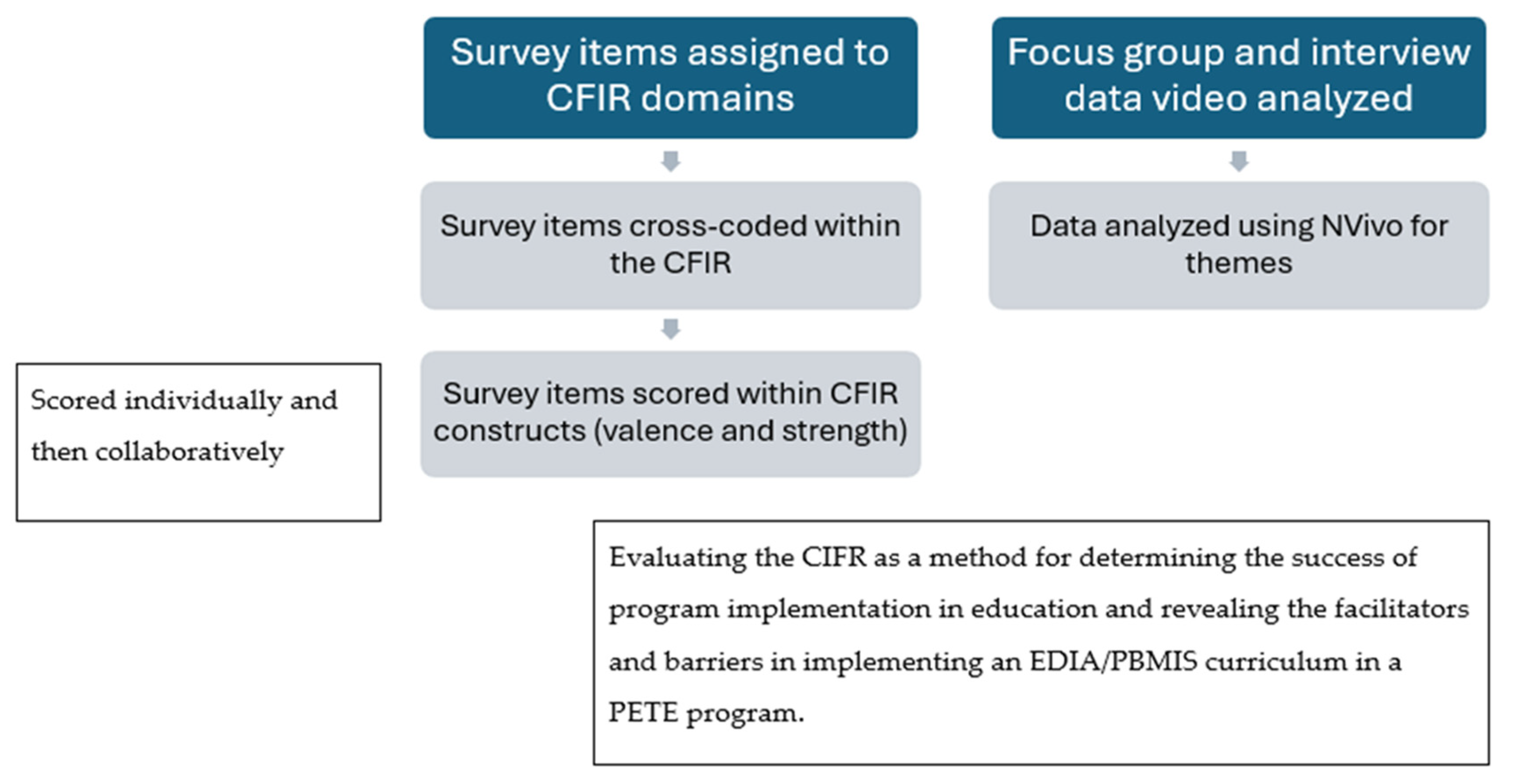

Survey items, designed collaboratively by researchers, a team of practicing PE teachers, and a group of six graduate student researchers, included 45 items rated on a five-point Likert scale (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree). These data were then coded within the CFIR framework.With reference to your past experiences as a student in PHE, your concepts of inclusion and diversity in PE prior to the course, your observations of your practicum placements, and your learning and growth through the courses, please answer with respect to how the course’s PLAY-based inclusive pedagogical intervention has impacted your learning and growth.

5.2.4. Videography

5.2.5. Videography of Two Online Focus Groups

5.2.6. Data Analysis

6. Results

6.1. Facilitators

6.2. Barriers

7. Discussion

Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Focus Group or Post-Interview questions

- Intervention characteristics—how the intervention is perceived by those PSTs

- Intervention source?

- Evidence strength and quality

- Did your practicum experiences support the implementation/use of a play-based modern instructional strategy (PBMIS)?

- If so how, if not, why not? What is your evidence?

- Relative Advantage

- What did you find to be the benefits or advantages to a PBMIS approach over more traditional instructional strategies or those used by your associate teacher?

- Adaptability

- Were there situations or contexts in which you had to rely on other instructional approaches?

- Trialability

- Complexity

- What, if any, roadblocks did you come across that impeded your implementation of this model of teaching? What made it difficult to implement this model?

- Design quality and packaging

- How did the students respond to the teaching methods? Were there difficulties in having them respond to the change in teaching method?

- Cost

- Outer setting—the school and PE community context

- Student needs and resources

- Was the school/system or your AT set up/working to serve the needs of your students in PE? Inclusive of all students?

- What would you identify as the main goal of PE in your school?

- External policies and incentives

- Were there structures or policies within the school or system, that impeded the implementation of PE using this model?

- Do you have recommendations for policy or procedures to support this form of teaching PE?

- Peer pressure

- Did your AT support your use of this style of teaching? Did other teachers in the school question your use of this teaching methodology? Did they assume it was just a new teacher’s enthusiasm and the reality of the job will have you teaching like them?

- Did you have colleagues that disagreed with this form of teaching PE, did you feel pressure to change to conform? Did this cause doubt in your beliefs?

- Cosmopolitanism—in line with other organizations—networked with external organizations

- Do you see support for this instructional paradigm in outside organizations, e.g., PHE Canada, OPHEA, TAPHE, on the internet?

- Inner setting

- Structural characteristics

- Culture

- Implementation climate

- Readiness for implementation

- Learning climate

- Relative priority

- Compatibility with organizational culture

- Organizational incentives and rewards

- How was your teaching method met within the PE department? School?

- Was assessment embedded in your AT’s teaching, in yours?

- Was your AT accepting of change? Is the school supportive of innovation and change?

- How does PE rank within the school? What is its relative importance as a subject?

- Did administration speak of innovation, change…?

- Individuals

- Knowledge and beliefs about intervention/self-efficacy

- Do you feel competent and confident in planning and teaching in this style?

- Did you find that this form of teaching supported the inclusion of all students in your class in PE?

- Do you feel that this teaching methodology, approach to PE is supportive of your PE pedagogy?

- Individual stage of change

- As this teaching methodology is likely different than what you had as a student, how confident are you in using the model and that it will be successful?

- Individual identification with the organization

- How is PE perceived within the school/region/province?

- How do you see yourself within the school community as a physical educator? Relative status?

- Other personal attributes

- What is it about you that helped you succeed with this style of teaching?, e.g., experience, attitude, motivation

- Implementation Process

- Planning—have the proper steps to promote effective implementation been established and put in place?… Could you describe some of the teaching strategies that you used to implement this form of teaching? How did you adapt your teaching to best support the needs of the students in your class (their specific context)? How did you measure your success as a physical educator?

- Engaging—who is involved in the implementation? Does it have a champion?

- Executing

- Reflecting and evaluating—did you reflect on your teaching daily? Did you consider your teaching strategies in your reflection? Was your teaching inclusive of all students in your class? Did your teaching provide students with physical literacy to live a healthy active lifestyle suited to them?

References

- Allen, M., Wilhelm, A., Ortega, L. E., Pergament, S., Bates, N., & Cunningham, B. (2021). Applying a race (ism)-conscious adaptation of the CFIR framework to understand implementation of a school-based equity-oriented intervention. Ethnicity & Disease, 31(1), 375–388. [Google Scholar]

- Armour, K., Quennerstedt, M., Chambers, F., & Makopoulou, K. (2015). What is ‘effective’ CPD for contemporary physical education teachers? A deweyan framework. Sport, Education and Society, 22(7), 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghurst, T. (2014). Assessment of effort and participation in physical education. The Physical Educator, 71, 505–513. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, W., Walters, J., & Walters, W. (2023). Teacher candidates’ critical reflections on inclusive physical education: Deconstructing our past and rebuilding new paradigms. PHEnex Journal, 13(2), 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, W., Walters, W., Bates, D., Waterbury, K., & Poulin, C. (2024). Building capacity: New directions in physical education teacher education. In M. Garcia (Ed.), Global innovations in physical and health education (pp. 491–516). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, W. S. (1995). Long-term effects of early childhood programs on cognitive and school outcomes. The Future of Children, 5(3), 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, T., & Eisner, E. W. (2011). Arts based research. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Beni, S., Chróinín, D. N., & Fletcher, T. (2021). ‘It’s how PE should be!’: Classroom teachers’ experiences of implementing Meaningful Physical Education. European Physical Education Review, 27(3), 666–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, T. (2021). Education reform in Ontario: Building capacity through collaboration. In F. M. Reimers (Ed.), Implementing deeper learning and 21st century education reforms: Building an education renaissance after a global pandemic (pp. 39–58). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Broadcast Company (CBC). (2023, December 10). Canadian students’ math, reading scores have dropped since 2018—But study says it’s not all COVID’s fault. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/canadian-students-pandemic-learning-match-science-reading-study-1.7049681 (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Cardona, M. I., Monsees, J., Schmachtenberg, T., Grünewald, A., & Thyrian, J. R. (2023). Implementing a physical activity project for people with dementia in Germany-Identification of barriers and facilitator using consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR): A qualitative study. PLoS ONE, 18(8), e0289737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, C., Patterson, M., Wood, S., Booth, A., Rick, J., & Balain, S. (2007). A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implementation Sci, 2, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, A., Fletcher, T., Schaefer, L., & Gleddie, D. (2018). Conducting practitioner research in physical education and youth sport. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, F. C., Luttrell, S., Armour, K., Bleakley, W. E., Brennan, D. A., & Herald, F. A. (2015). The pedagogy of mentoring: Process and practice. In F. C. Chambers (Ed.), Mentoring in physical education and sports coaching (pp. 28–38). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Clandinin, D. J. (2013). Engaging in narrative inquiry. Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Conference Board of Canada. (2000). Employability skills 2000+. Conference Board of Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Curtner-Smith, M. D. (2001). The occupational socialization of a first-year physical education teacher with a teaching orientation. Sport, Education and Society, 6(1), 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damschroder, L. J., Reardon, C. M., Widerquist, M. A. O., & Lowery, J. (2022). The updated consolidated framework for implementation research based on user feedback. Implementation Science: IS, 17(1), 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. (1922). Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education (4th ed.). Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fixsen, D. L., Naoom, S., Blase, K., Friedman, R., & Wallace, F. (2005). Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature. The National Implementation Research Network. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, M. (1998). Education reform: Are we on the right track? Canadian Education Association, 38(3), 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow, R. E., Eckstein, E. T., & El Zarrad, M. K. (2013). Implementation science perspectives and opportunities for HIV/AIDS research: Integrating science, practice, and policy. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 63, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, L. (2022, September 7). Students do well in global testing, but scores falling. The Toronto Sun. Available online: https://torontosun.com/opinion/columnists/goldstein-students-do-well-in-global-testing-but-scores-falling-says-report (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Greenberg, M. T., Domitrovich, C. E., Graczyk, P. A., & Zins, J. E. (2005). The study of implementation in school-based preventive interventions: Theory, research, and practice. In Promotion of mental health and prevention of mental and behavior disorders (Vol. 3). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, M. (1995). Releasing the imagination: Essays on education, the arts, and social change. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks, B. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A. R. (2018). Grading in physical education. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 89(5), 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, B., & Perkins, D. F. (Eds.). (2012). Handbook of implementation science for psychology in education. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M. L., Jr. (1947). The purpose of education. The Maroon Tiger. Morehouse College. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, M. A., Kelley, C., Yankey, N., Birken, S. A., Abadie, B., & Damschroder, L. (2016). A systematic review of the use of the consolidated framework for implementation research. Implementation Science, 11(1), 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyon, A. R., Cook, C. R., Brown, E. C., Locke, J., Davis, C., Ehrhart, M., & Aarons, G. A. (2018). Assessing organizational implementation context in the education sector: Confirmatory factor analysis of measures of implementation leadership, climate, and citizenship. Implementation Science, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martos-García, D., & García-Puchades, W. (2023). Emancipation or simulation? The pedagogy of ignorance and action research in PETE. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 28(1), 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshkovska, B., Scheller, D. A., Wendt, J., Jilani, H., Scheidmeir, M., Stratil, J. M., & Lien, N. (2022). Barriers and facilitators to implementation of direct fruit and vegetables provision interventions in kindergartens and schools: A qualitative systematic review applying the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR). The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 19(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moir, T. (2018). Why is implementation science important for intervention design and evaluation within educational settings? Frontiers in Education (Lausanne), 3, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Assessment of Educational Progress. (2024, August 28). About NAEP: A common measure of student achievement. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/about/ (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Olswang, L. B., & Prelock, P. A. (2015). Bridging the gap between research and practice: Implementation science. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 58(6), S1818–S1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2023). PISA 2022 results (Volume I): The state of learning and equity in education. PISA, OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2024, August 28). Programme for international student assessment (PISA). Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/about/programmes/pisa.html (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Ovens, A., & Fletcher, T. (Eds.). (2014). Self-study in physical education teacher education: Exploring the interplay of practice and scholarship. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis, A., Lutovac, S., Jokikokko, K., & Kaasila, R. (2019). Towards a relational understanding of teacher autonomy: The role of trust for Canadian and Finnish teachers. Research in Comparative and International Education, 14(3), 394–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- People for Education. (n.d.). Broader measures of success: Measuring what matters in education. People for Education. Available online: https://peopleforeducation.ca/report/broader-measures-of-success-measuring-what-matters-in-education/#chapter8 (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Peters, D. H., Adam, T., Alonge, O., Agyepong, I. A., & Tran, N. (2013). Implementation research: What it is and how to do it. The British Medical Journal, 48(8), 731–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirrie, P., & Manum, K. (2024). Reimagining academic freedom: A companion piece. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 58(6), 895–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintão, C., Andrade, P., & Almeida, F. (2020). How to improve the validity and reliability of a case study approach? Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Education, 9(2), 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, K. A. R. (2015). Role socialization theory: The sociopolitical realities of teaching physical education. European Physical Education Review, 21(3), 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D. B., Harenberg, S., Walters, W., Barrett, J., Cudmore, A., Fahie, K., & Zakaria, T. (2023). Game Changers: A participatory action research pilot project for/with students with disabilities in school sports settings. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 5, 1150130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, K. (2021). An essay on the challenges of doing education research in Canada. Journal of Applied Social Science, 15(2), 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshan, R., Hamid, S., Kumar, R., Hamdani, U., Naqvi, S., Zill-e-Huma, & Adeel, U. (2025). Utilizing the CFIR framework for mapping the facilitators and barriers of implementing teachers led school mental health programs—A scoping review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 60(3), 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldana, J. (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (2nd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon, D., Beckey, A., Wintle, J., & Hordvik, M. (2024). ‘Weak’physical education teacher education practice: Co-constructing features of meaningful physical education with pre-service teachers. Sport, Education and Society, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, R. E. (2002). Evidence-based education policies: Transforming educational practice and research. Educational Researcher, 31(7), 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaresan, N., Dashoush, N., & Shangraw, R. (2017). Now that were “well rounded”, let’s commit to quality physical education assessment. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 88(8), 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Touchette, A. (2020). The consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR): A roadmap to implementation. KnowledgeNudge. Available online: https://medium.com/knowledgenudge/the-consolidated-framework-for-implementation-research-cfir-49ef43dd308b (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Tucker, S., McNett, M., Mazurek Melnyk, B., Hanrahan, K., Hunter, S. C., Kim, B., Cullen, L., & Kitson, A. (2021). Implementation science: Application of evidence-based practice models to improve healthcare quality. Worldviews Evidence Based Nursing, 18(2), 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volante, L. (2005). Accountability, student assessment, and the need for a comprehensive approach. International Electronic Journal for Leadership in Learning, 9(6), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Volante, L. (2010). Standards-based reform: Could we do better? Education Canada, 47(1), 54–56. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, W., MacLaughlin, V., & Deakin, A. (2023). Perspectives and reflections on assessment in physical education: A self-study narrative inquiry of a pre-service, in-service, and physical education teacher educator. Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education, 14(1), 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T. L., & Lien, Y. H. B. (2013). The power of using video data. Quality and Quantity: International Journal of Methodology, 47(5), 2933–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design (2nd ed.). Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum (WEF). (2023). The future of jobs report 2023. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-future-of-jobs-report-2023/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Yin, R. K. (2017). Case study research and applications: Design and methods. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Zeigler, E. F. (2005). History and status of American physical education and educational sport. Trafford. [Google Scholar]

| Facilitators | Survey Items |

|---|---|

| Intervention Characteristics | The features of this course/learning experiences challenged my perceptions of what inclusive PHE means. I learned strategies and methods to develop inclusive PHE classes. I designed effective lesson plans based on UDL (Universal Design for Learning), inclusion, diversity, and accessibility. I learned the advantages to designing and implementing fully inclusive PHE classes. I can identify the perceptions of privilege, power, and normative notions of ability and disability. This overall experience allowed me to deconstruct and reconstruct ideas of ability vs. disability. |

| Outer Setting | The provincial curriculum and policies support fully inclusive PHE. My practicum placement experience was in a school board/regional center that has an inclusion and diversity policy. My overall Bachelor of Education experience demonstrated fully inclusive pedagogy across subjects. My university course experience modeled fully inclusive PHE pedagogy. External organizations (e.g., PHE Canada, OPHEA, TAPHE, CIRA) support fully inclusive PE pedagogy. |

| Inner Setting | The classroom climate for my pre-service PHE teacher education course was inclusive and welcoming. Class leader(s), teachers, and guest speakers modeled climate-building and inclusion. The setting of the class was inclusive for teacher candidates of all abilities. The setting of the class was inclusive for teacher candidates of all races, cultures, and genders. The PETE classroom was a safe setting for all participants regardless of ability level. |

| Characteristics of Individuals | I witnessed intentional pedagogical strategies to build community by the instructor(s). The instructor demonstrated knowledge and belief that play-based inclusion was essential to PETE. I felt fully included by my classmates, and was encouraged to participate at my own level. I felt a sense of belonging in class based on the instructor’s approaches to inclusive PETE. Inclusive PE pedagogical strategies used in this course created a strong sense of community. I was encouraged to learn from, and with my classmates of different ability levels, cultures. I developed confidence and competence for inclusive PE pedagogy as a result of this experience. As a result of this PETE course, I feel committed to building inclusive PE pedagogy for my students. Student voice in PETE classes was honored and respected. I was encouraged to develop resilience and grit as a beginning PE teacher. I was encouraged to prioritize self-care in order to be at my best as a PE teacher. |

| Process | I was provided with time to reflect on my learning about inclusion. I was guided to literature regarding inclusive pedagogy. I was able to self and peer assess and evaluate my learning in the inclusive PETE course. In my practicum placement, I was provided time to reflect on how inclusion and diversity were in my lesson designs. |

| Barriers | Survey Items |

|---|---|

| Intervention Characteristics | I observed fully inclusive PHE classes in my practicum placement experiences. I discovered barriers to implementation in my practicum placement experiences. |

| Outer Setting | My associate teacher was aware of school board/regional center policies on inclusion. I received support to design and implement inclusive PE during my practicum placement. I observed inclusion and diversity being implemented in my practicum placement. School timetables are designed to be supportive of inclusive design for PHE. |

| Inner Setting | Was my practicum placement school culture supportive of innovation and change? Did I observe resistance to the development of full inclusion in my placement school? I observed PE classes that were inclusive for students of all abilities. I observed PE classes that were inclusive for students of all races, cultures, and genders. |

| Characteristics of Individuals | I see representation or role models from my culture in the field of PE pedagogy. |

| Process | None |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Walters, W.; Barber, W.; Jutras, M. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research: Application to Education. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 613. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050613

Walters W, Barber W, Jutras M. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research: Application to Education. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(5):613. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050613

Chicago/Turabian StyleWalters, William, Wendy Barber, and Mickey Jutras. 2025. "The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research: Application to Education" Education Sciences 15, no. 5: 613. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050613

APA StyleWalters, W., Barber, W., & Jutras, M. (2025). The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research: Application to Education. Education Sciences, 15(5), 613. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050613