Young children are naturally inclined to learn and explore mathematical concepts within their everyday surroundings (

Linder et al., 2011;

National Association for the Education of Young Children & National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 2010). Their innate curiosity serves as a foundation for not just mathematics, but also early development of science, technology, engineering, (arts) and mathematics (STEM/STEAM) interests and achievement. However, traditional kindergarten classrooms may not provide children with opportunities to learn mathematics or other STEAM content domains through responsive, inquiry-driven instructional formats, particularly skills related to spatial reasoning (SR) (

Davis & Spatial Reasoning Study Group, 2015;

Sinclair & Bruce, 2015;

Wai et al., 2009;

Wien, 2015). SR is considered “the ability to recognize and (mentally) manipulate the spatial properties of objects and the spatial relations among [them]” (

C. D. Bruce et al., 2017, p. 146), which is crucial for mathematics and academic achievement, plus STEM education and careers (

Duncan et al., 2007;

Gilligan-Lee et al., 2022;

Wai et al., 2009;

Wai & Uttal, 2018). While some SR abilities can develop through everyday interactions in our world, like navigating the environment (

Ishikawa & Newcombe, 2021) or packing a suitcase (

Harris, 2021), spatial thinking can also be taught and learned (

National Research Council, 2006;

Uttal et al., 2013).

The skills comprising SR allow humans to “recall, generate, manipulate, and reason about spatial relations” (

Gilligan-Lee et al., 2022, p. 1) and are foundational to many mathematical concepts, including numeracy (

Harris, 2021;

National Research Council, 2006;

Uttal et al., 2013). The mathematics taught in early childhood classrooms, including kindergarten, tends to focus on numeracy and number sense, yet SR is infrequently emphasized despite the established relation between the skills (

C. Bruce et al., 2012;

Clements & Sarama, 2011;

Copley, 2010). School-based mathematics learning opportunities, instead, generally align with five major mathematical domains (number and operations, geometry, measurement, algebra, and data analysis;

National Association for the Education of Young Children & National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 2010), from which SR is generally absent within corresponding written curricula or education standards (

Gilligan-Lee et al., 2022;

Pinilla, 2024b). Despite evident opportunities to teach SR through the aforementioned mathematical domains (geometry and measurement;

Clements & Sarama, 2011), SR skills are generally represented implicitly in education standards (

Boda et al., 2022;

Pinilla, 2024b) and could be better emphasized in instruction through developmentally appropriate activities in which children are already engaged. Specifically, as explored in this study, the data analysis domain offers connections to visual representations of non-spatial concepts, such as graphs, that can support SR learning through conceptual mappings (

Gattis, 2002;

Taylor et al., 2023).

One educational model that can promote such developmentally appropriate and integrated mathematics, and, in turn, STEAM learning, that cultivates children’s curiosity is the Reggio Emilia-Inspired Approach (RE-IA) (

Linder et al., 2011;

McCormick Smith & Chao, 2018). The RE-IA is a progressive educational philosophy that emphasizes child-centered, inquiry-based learning through emergent curricula (

Malaguzzi, 1996). Within the RE-IA, children are viewed as competent, resourceful, and capable of constructing their own knowledge with the support of teachers acting as facilitators (

Biermeier, 2015) and are supported through a more exploratory, collaborative learning environment than traditional classrooms, wherein they are encouraged to discover mathematical concepts through hands-on projects and real-world applications (

New, 2007). To support whole child development as doers of mathematics (

National Research Council, 2001), children need opportunities to learn multiple domains of mathematics, which should include opportunities to learn and practice SR, though it is not currently recognized as a domain of mathematics (

Copley, 2010;

National Association for the Education of Young Children & National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 2010).

Empirical studies have emphasized the importance of children learning SR (

Hawes & Ansari, 2020;

Verdine et al., 2017;

Wai et al., 2009), identified the gap between research and practice specific to these skills (

Farran et al., 2024), and encouraged teachers to integrate the skills in lessons through professional development (

Hawes et al., 2017;

Moss et al., 2015). Separately, research has found that there is power in authentic learning experiences offered by programs utilizing the RE-IA (

McCormick Smith & Chao, 2018;

Fernandez Santín & Feliu Torruella, 2017;

Strong-Wilson & Ellis, 2007). Given documented benefits of providing children with interactive mathematics projects using the RE-IA, this study examines the opportunities to learn SR embedded within a kindergarten mathematics project and how common mathematics education standards might be addressed through such inquiry-based learning to provide more opportunity for transdisciplinary STEAM learning.

1. Theoretical Foundation

This study utilizes a social constructivist lens and literature on SR and RE-IA to investigate how SR skills can appear in an early childhood educator’s practice at a school that uses the RE-IA. Social constructivism theoretically undergirds the study, as the very nature of the RE-IA includes children actively constructing knowledge within an inquiry-based learning environment (

Strong-Wilson & Ellis, 2007). Teachers using the RE-IA serve as learning guides, position children as competent beings, and create environments that provide expansive opportunities to learn ideas of interest to the children themselves, promoting authentic experiences through emergent curriculum (

Biermeier, 2015;

Fraser & Gestwicki, 2002). Unlike the notion of internal, stage-wise development conceived through Piagetian constructivism, the RE-IA focuses on interaction and children’s learning with and through relationships with others (

Biermeier, 2015;

Malaguzzi, 1996;

Mooney, 2013).

Considering the centrality of interaction in the RE-IA, we believed it important to ensure SR is also discussed through interaction and integration. Whereas there are calls for SR to be more integrated in early childhood mathematics and STEM teaching and learning (

Davis & Spatial Reasoning Study Group, 2015;

National Research Council, 2006) and there have been theoretical investigations on the linkages between RE-IA and STEM (

Hachey & Mehta, 2024), little research has attempted to answer those calls through active change in the classroom. We thus borrow from

Armstrong’s (

2019) framework to support constructivism in inclusive educational settings through action research to understand the SR learning opportunities in a classroom using the RE-IA.

2. Literature Review

We herein describe the importance of SR learning opportunities and benefits of providing children with interactive mathematics projects using the RE-IA to both underscore the intersection of these literatures in grounding this study and support transdisciplinary STEAM learning opportunities.

2.1. Spatial Reasoning

SR is comprised of a set of skills foundational to number sense, as the skills allow humans to mentally represent and transform objects and their relations (

Harris, 2021;

Mulligan, 2015). Whereas number sense is omnipresent in early childhood mathematics curricula (

Clements & Sarama, 2011;

Gilligan-Lee et al., 2022) and education standards, such as the Common Core State Standards for Mathematics (CCSS-M;

National Governors Association, 2010) or Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills (TEKS;

Texas Education Agency, 2024), SR receives less focus despite its linkage to mathematics development (

Hawes & Ansari, 2020;

Mix & Cheng, 2012). By integrating SR activities (e.g., transforming objects, composing and decomposing figures) into typical mathematics instruction (e.g.,

Hawes et al., 2017), educators can provide learning opportunities that encourage children to explore and manipulate their surroundings to develop SR skills. However, educators may need support to do so, and the available supports may be constrained by existing curricula, educational standards, or pedagogical practices.

2.1.1. Spatial Reasoning in Curriculum and Standards

Gilligan-Lee et al. (

2022) described the significant challenge of teaching SR when the skills are not explicit in education standards. While

Boda et al. (

2022) identified opportunities to teach some SR skills through the CCSS-M for early elementary, the opportunities are mostly implicit (

Pinilla, 2024b), meaning that SR is not the focus of the standard, and thus, there may or may not be opportunities to learn SR through standards-based lessons, depending on a teacher’s pedagogical practices. Early elementary mathematics education standards often limit the extent to which SR is formally taught to just identifying shapes and describing their properties (

Gilligan-Lee et al., 2022;

Verdine et al., 2016). While the skills are often seen as best aligning to geometry standards and curriculum (

Clements & Sarama, 2011;

Sinclair & Bruce, 2015), SR is broader than that single mathematics domain and can be taught through other school-based content areas, such as social studies (

Mohan & Mohan, 2014) and visual arts (

Lee, 2023).

The broad connections are supported by the extensive literature on visualization, or the ability to imagine and mentally transform spatial representations (

Pinilla, 2024a;

Clements et al., 2004;

Linn & Petersen, 1985;

McGee, 1979), as one of the primary SR constructs. Within mathematics, visualization interrelates with students learning graphing (

Gattis, 2002;

Taylor et al., 2023) and data analysis or modeling skills (

Mulligan et al., 2018). More broadly, SR is used in geography to read maps and in visual arts when creating works that require taking alternative perspectives (

Gilligan-Lee et al., 2022;

Lee, 2023); these applications outside of mathematics education may enhance educational success, particularly in STEAM fields (

Wai & Uttal, 2018), meaning that support for teaching SR cannot be limited to providing curriculum. Support should include professional learning opportunities for teachers to enhance pedagogy, as well.

2.1.2. Spatial Reasoning in Pedagogy and Professional Learning

Farran et al. (

2024) reiterated that professional learning specific to SR skills is critical in bridging the research-to-practice gap for teaching SR (

Hawes et al., 2017;

Moss et al., 2015;

Resnick & Lowrie, 2023). Studies conducted in various settings have included opportunities for teachers to learn how to teach SR while using their typical mathematics curriculum or a specific program.

Moss et al. (

2015) described an adaptation of Japanese Lesson Study in which they guided five Canadian early grades teachers in (a) engaging with the mathematics of SR, (b) co-designing tasks for clinical interviews with children, (c) exploring activities and lessons, and (d) creating resources. Through these experiences, teachers, who were initially reluctant to stray from the procedural experiences detailed in their curriculum, began rethinking their pedagogical practice and their conceptions of geometry content; the professional learning gave them new insights from research into their own practice. Likewise,

Hawes et al. (

2017) worked with 12 Canadian early grades teachers to understand differences in pedagogical practice as related to SR teaching and learning. They found that, while using the same curriculum, students in the classes of teachers who learned specific spatially related pedagogies improved in spatial language, visual-spatial geometry, and 2D mental rotation skills to a greater extent than their peers in classrooms led by control group teachers. Together, these studies demonstrate that pedagogical practices emerging from professional learning opportunities can support SR teaching and learning.

Whereas both examples of studies conducted in Canada relate to mathematics, Australia has a national early childhood curriculum that supports STEM teaching and learning more broadly.

Resnick and Lowrie (

2023) reported on how professional learning opportunities about the Early Learning STEM Australia (ELSA) curriculum, plus additional spatial tools and training on how to “spatialize the curriculum,” supported greater student gains than training on the curriculum alone. By having children interact with various representations, visualize paths before traversing them, and use gestures to communicate about SR, they demonstrated greater gains in SR skills than peers who did not experience those spatialized learning opportunities. However, the relation of said SR learning to STEAM domains other than mathematics was not reported.

2.1.3. A Framework of Spatial Reasoning Skills

Historically, SR has been investigated in psychology, with skills assessed using psychometric tests (e.g.,

McGee, 1979;

C. D. Bruce et al., 2017). However, assessing skills in this way is inadequate to bolster pedagogical practices, as supporting instruction is not the intended use of such tests (

American Educational Research Association et al., 2014). In attempt to answer repeated calls to integrate SR into education (

Davis & Spatial Reasoning Study Group, 2015;

National Research Council, 2006;

Pinilla, 2024a) adapted and defined the terms in a model of SR skills intended to articulate the skills young children could learn and demonstrate to help educators know what the skills are so they could provide appropriate learning opportunities. The framework describes high-level skills comprising spatial reasoning that are generally captured within categories of:

altering, constructing, interpreting, moving, sensating, and

situating (

Pinilla, 2024a;

Davis & Spatial Reasoning Study Group, 2015). Each category is comprised of other subskills (see

Appendix A for general definitions and all skills), of which few are named in education standards or written curricula (

Pinilla, 2024b;

Gilligan-Lee et al., 2022).

Given the importance of SR for mathematics learning, but its lack of explicit inclusion in most curricula, finding pedagogical approaches that support opportunities to learn SR being present is critical. The constructivist approach to emergent curricula that is foundational to the RE-IA provides a potential avenue for SR to be included in mathematics and other STEAM domain learning opportunities.

2.2. Reggio-Emilia Instructional Approach

Developed in Reggio Emilia, Italy, by educator Loris Malaguzzi, this approach to early childhood education views children as competent, resourceful, and capable of constructing their own knowledge with the support of teachers, who act as facilitators rather than traditional instructors (

Biermeier, 2015). The RE-IA is rooted in constructivist principles and emphasizes the importance of rich, interactive learning environments to foster children’s curiosity and creativity (

Gandini, 1993). Considering the types of learning experiences children receive within schools adopting this approach, Reggio inspired activities nurture individual and group discovery and encourage exploration by supporting students to use their five senses, ask questions, test theories, make and verbalize plans, and think deeply (

Desouza & Jereb, 2000;

McCormick Smith & Chao, 2018;

New, 2007;

Rinaldi, 2021;

Vatalaro et al., 2015). It is through these activities that children can demonstrate their learning, expressing themselves as they see fit (

Malaguzzi, 1996).

Unlike most mathematics learning opportunities provided to children in typical public schools, mathematics projects based on the RE-IA are emergent, extended in duration, and co-designed by children to offer opportunities to learn about topics and concepts of interest to them (

Gandini, 1993). The projects also provide opportunities for physical interaction and are thus believed to support the development of SR skills. Specifically, collaborative projects and hands-on experiences, which are central to its instructional philosophy (

New, 2007), represent a hallmark difference between RE-IA and more traditional education models worthy of investigation when seeking alternative pedagogies.

3. Objectives and Research Questions

This study employed action research methods (

Mills, 2014) to systematically engage with and examine the teaching practices of a kindergarten teacher and SR learning opportunities for their students at a school that utilizes the RE-IA. The project was field initiated, as aligned with the tenet of action research in classrooms being driven by educators examining the issues they encounter by reflecting on the situation, collecting and analyzing data, and making changes based on the findings (

Mills, 2014), and intended to improve the teacher’s SR teaching and student learning while engaged in a mathematics project. Specifically, this action research allowed an innovative approach to exploring relations between SR skills and classroom activities, through which we investigated the following research questions:

RQ1.

How can spatial reasoning skills be learned through a Reggio-inspired mathematics project?

RQ2.

What connections can be drawn between spatial reasoning skills and specific kindergarten mathematics educational standards?

While existing research describes how inquiry learning in responsive classroom environments fosters meaningful discovery learning (i.e., RE-IA) and the importance of SR to overall mathematics learning (

Hawes & Ansari, 2020;

Mix & Cheng, 2012), this study contributes to the literature by connecting RE-IA with the teaching of SR.

4. Methods

This study used action research methods (

Mills, 2014) to examine a kindergarten teacher’s mathematics instructional practices and their students’ SR learning opportunities. We identified the problem of SR not being explicitly stated in lesson plans or curriculum planning documents, but believed there were likely opportunities present through instructional enactments and children’s learning actions. We iteratively explored this conjecture to identify opportunities for learning SR within a mathematics project.

4.1. Participants and Context

Participants included ten kindergarten students (aged 4–7) and the study’s secondary researcher, who served as the classroom teacher. The study took place at a small, private school in the Southwest United States (U.S.) that used the RE-IA and occurred in late winter 2024. The study was approved by the University Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the RE-IA school’s program director. All participating children’s parents consented to their participation, which did not interfere with their typical educational experiences. Further, no specific information about the children, such as their performance on individual tasks, was collected; instead, field notes about their interaction with tasks were taken at the aggregate level, and photos were taken as artifacts without identifiable features (e.g., faces, clothing) to ensure confidentiality. Information about the teacher/secondary researcher is included in the positionality section.

Regarding the duration of the project within this context, the school day was six hours in length, with 45 to 60 min daily dedicated to mathematics teaching and learning. This study was completed in one school week, from Monday through Friday, allowing for approximately four hours to be dedicated to the focus project, plus any additional time the children chose to continue engaging with the concepts.

4.2. Data Sources and Collection

All data were collected during one week in spring 2024 when the class engaged in a guided mathematics project about data analysis concepts. Data sources included available documents and artifacts used in the classroom (physical materials and manipulatives, lesson planning documents), researcher-generated artifacts created when students engaged in the project (students’ written work and deidentified photos of their classroom engagements), and publicly available records (i.e., Child Observation Record [COR] Advantage Objectives (

HighScope, 2013) and the kindergarten mathematics TEKS (

Texas Education Agency, 2024)). All data were stored in a secure folder in IRB-approved cloud storage (OneDrive) and accessed only by project researchers. No individual student names or identifying information were collected or retained in the data corpus.

After the research team discussed the idea that children may experience opportunities to learn SR through their mathematics project during the target week, they followed the three phases of

Creswell and Guetterman’s (

2019) action research data collection recommendations: experiencing, enquiring, and examining. First, in the “experiencing” phase, the secondary researcher observed their students’ learning engagements while acting as the classroom facilitator and generating field notes and artifacts (photos). During the week-long mathematics project, the teacher/secondary researcher engaged children using classroom materials (see

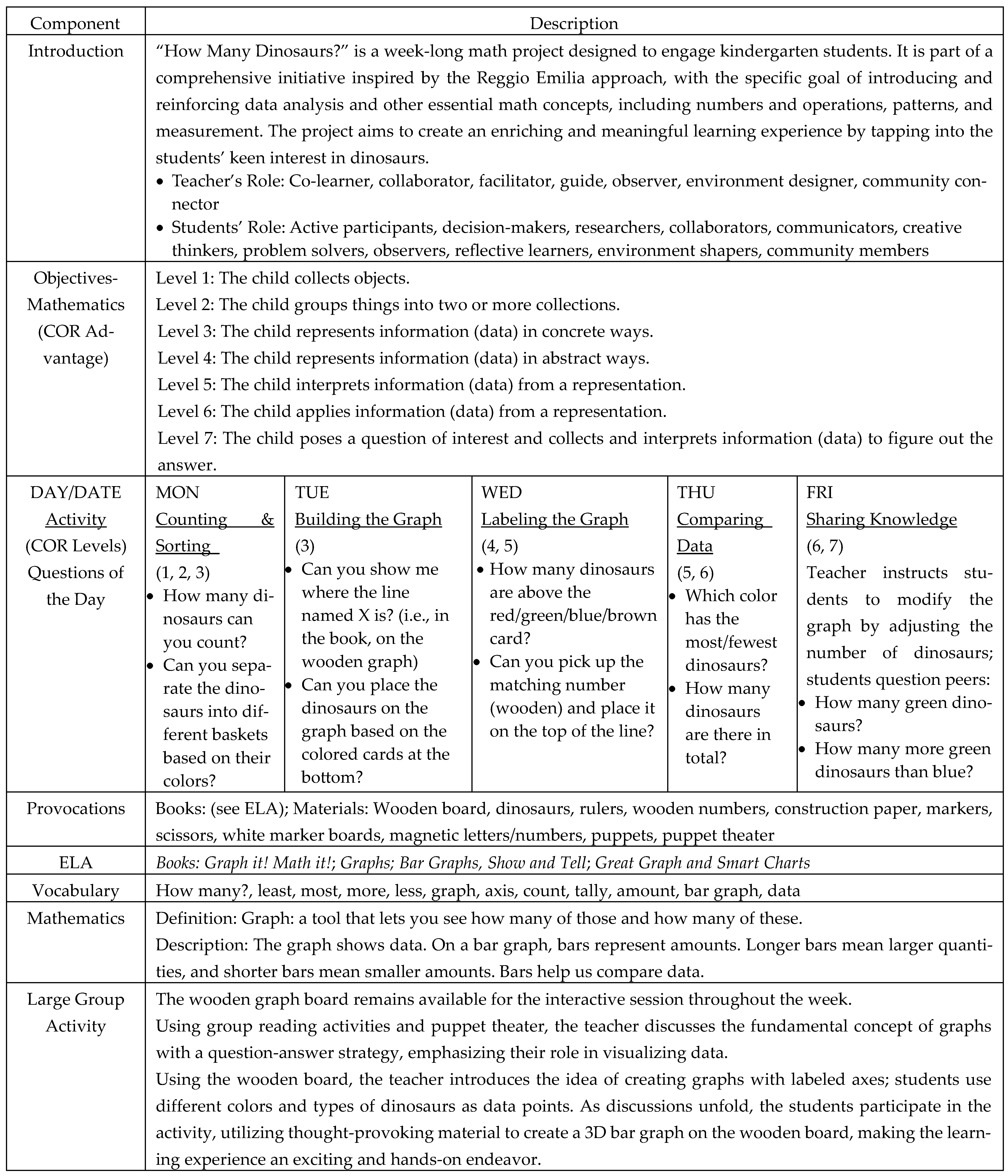

Figure 1), aiming to progressively deepen their conceptual understanding of data analysis concepts. On Day 1, the teacher read books during English Language Arts (ELA) instruction about graphs and encouraged children to discuss the concepts through puppet theater before collaboratively designing and creating a large wooden graph board on which they would model with materials to create real-object graphs. On Day 2, the teacher used direct teaching to inform students about the characteristics of graphs and supported them in representing quantities on a physical board as they constructed a bar graph. On Days 3, 4, and 5, children became increasingly independent with creating graphs, manipulating their representations, and questioning one another about their interpretations, as reflected in the lesson plans that included the corresponding COR Advantage standards listed on each day’s “Question of the Day.” See

Figure 1 for a detailed lesson planning document.

Next, in the “enquiring” phase, the primary and secondary researchers, together, developed research questions about how SR learning opportunities were integrated within the week’s mathematics project and how those opportunities aligned with mathematics education standards used in local public schools. Third, in the “examining” phase, the researchers compiled and analyzed the data to understand the extent to which SR was present in the project so that the teacher could be more intentional in offering SR learning opportunities moving forward.

4.3. Data Analysis

After individually reviewing data sources and writing preliminary jottings, we used hypothesis and descriptive coding simultaneously (

Saldaña, 2016) to (1) explore how SR can be learned through a Reggio-inspired mathematics project and (2) identify connections between the project and local education standards.

We hypothesized that the teacher/secondary researcher was offering children opportunities to learn SR through mathematics projects and that those skills could relate to both the indicators used in the school (i.e., the COR Advantage Objectives) and more widely adopted educational standards (i.e., the kindergarten mathematics TEKS). Based on these conjectures, we adopted hypothesis codes from a framework of SR skills (

Pinilla, 2024a) to answer RQ1, and content-specific TEKS for kindergarten mathematics (

Texas Education Agency, 2024) to answer RQ2. The standard selected, TEKS K(b)8 (i.e., “The student applies mathematical process standards to collect and organize data to make it useful for interpreting information;”

Texas Education Agency, 2024, p. 9), describes what children at this age are expected to learn of data analysis skills. We also adopted descriptive codes of what we

knew was taking place based on the school type at which the teacher/secondary researcher taught, which were characteristics of RE-IA and the COR Advantage Objectives (

HighScope, 2013). See the code list in

Table 1 and definitions in

Appendix A.

The primary and secondary researchers independently applied the codes to the data of interest for each research question. For research question 1, we examined lesson plans and researcher-generated artifacts to understand the SR learning opportunities offered (e.g., see

Appendix B for the coded version of the lesson plan). For research question 2, we examined findings from research question 1 plus the kindergarten mathematics standard believed to align with the project (i.e., TEKS K(b)8;

Texas Education Agency, 2024) and its objectives to understand relations.

After independently coding and comparing analyses, researchers met to debrief and find agreement about the learning opportunities and alignment with local education standards (the TEKS for kindergarten mathematics). Engaging in collaborative debrief sessions supported the trustworthiness of findings (

Merriam, 1998) as the researchers had both etic (primary) and emic (secondary) perspectives on the data, which allowed nuances of both objectivity and firsthand perceptual knowledge to be included. Then, after analyzing the coded data, we compared them to the hypotheses and narrated findings using thick, rich descriptions (

Lincoln & Guba, 1985) supported by field notes (i.e., triangulation) and data displays to support transferability.

4.4. Positionality

The primary researcher is a faculty member in early childhood mathematics teacher education at a public, research-intensive, Hispanic Serving Institution in the Southwest U.S. They taught prekindergarten and early elementary grades for nine years in public elementary schools and private childcare centers located in an urban area of the same general region in which the research was conducted. The secondary researcher is an educator born and raised in India who has over 20 years of experience teaching young children. They were engaged in doctoral study, investigating STEM education, and in their third year teaching kindergarten at the Reggio Emilia-inspired school at which this study was conducted. The researchers had previously collaborated to align a set of SR skills (

Pinilla, 2024a) with local kindergarten mathematics standards (TEKS;

Texas Education Agency, 2024), which provided a unique lens to view the mathematics activities taking place in the secondary researcher/teacher’s classroom that was not typically considered at the school. That lens encouraged the researchers to engage in this action research to examine how SR skills were taught while kindergarteners participated in their typical mathematics learning activities.

5. Findings

This section describes the SR learning opportunities afforded to kindergarten-aged children through a RE-IA mathematics project and how those opportunities aligned with local mathematics education standards. To answer Research Question 1, we analyzed lesson plans for evidence of SR teaching and learning (i.e., related to skills defined within the selected framework; see

Pinilla (

2024a)) and found relationships between the six overarching types of SR and the teacher’s instructional offerings. To answer Research Question 2, we examined the featured mathematics project to identify connections with kindergarten mathematics education standards (i.e., TEKS for kindergarten mathematics;

Texas Education Agency, 2024).

5.1. Opportunities to Learn Spatial Reasoning Through a RE-IA Mathematics Project

In response to research question 1, we found that children had opportunities to learn and practice all six overarching types of SR in the framework (

altering, constructing,

interpreting, moving,

sensating, and

situating; see hypothesis codes in

Table 1 and definitions in

Appendix A), either explicitly through the mathematics project as guided by the teacher and classroom environment or implicitly through students’ learning actions.

Table 2 describes how the teacher facilitated various components of the mathematics project, including the role of the learning environment, the actions the children took, and the connections to SR skills. Importantly, none of the learning actions or opportunities to learn and practice SR occurred in isolation, so results are reported first based on the activity (see

Figure 1) with the type of SR being practiced included in the narrative, then using examples of a subset of SR skills to demonstrate the framework used in analysis. The findings related to the opportunities are detailed using thick, rich descriptions of the activities and actions to support readers’ ability to visualize the learning. As an additional note to readers, SR skills are denoted using italic text throughout the narrative; all skills are listed in

Appendix A and defined comprehensively by

Pinilla, 2024a).

5.1.1. The Mathematics Project

Before the project began, the teacher facilitated students in co-creating the graph board (i.e., a large wooden board with columns and rows that would be labeled with X and Y axes). The teacher read books about graphing to the students (see lesson plan in

Figure 1) to support the students’ understanding of data

visualization and

interpretation, or help them imagine and draw inferences about what representations mean. Then the teacher and students co-

designed (conceived of and mentally planned) the graph and

modeled (created a small-scale version of) what the board could look like with popsicle sticks before creating the graph by

constructing the parts into a whole graph with columns and rows on the board.

The teacher also hosted a discussion about the graph before students began using it in their collaborative project, imparting knowledge about the x- and y-axes when reading a physical object graph. For the purposes of the class’s mathematics project, categories would be represented by columns along the x-axis, and quantities would be counted along the y-axis. The teacher helped label the axes and requested that students decide the type of objects they would like to use as data; they chose toy dinosaurs.

During Activity 1 of the project, the teacher requested students collect and bring their data (toy dinosaurs) to the central classroom location where the graph was located and sort them by color (blue, brown, green, and red). While collecting their data, students experienced opportunities to learn or practice sensating skills, as they perceived the dinosaurs through their senses (e.g., tactilizing—perceptible by touch). When sorting the dinosaurs by color, they practiced using situating skills by placing them in categories, then interpreting skills by drawing conclusions about the data, such as estimating and confirming quantities when sorting and counting. While engaged in this activity, students’ attention was drawn to the wooden graph they had helped to create, which was sectioned, or divided into parts as columns that they would use when creating the real-object graph.

During Activity 2, students used dinosaurs they had previously situated into groups by color to construct the graph. They physically manipulated dinosaurs by moving or sliding them across the board, which helped them practice spatial transformations like rotating and situating them in the columns. They compared the axes and number of dinosaurs on the graph to interpret quantities; in other words, they judged the sameness or difference in quantity to the marking on the y-axis by mapping correspondences and then drew inferences about the representations. They related, or established a connection between, the real-object graph and the numeric symbol on the y-axis when reading the graph. As an extension activity, students also changed the physical placement of dinosaurs (i.e., altered the placement and thus, the overall spatial structure), which introduced an implicit opportunity to experience additional SR concepts through the activity.

During Activity 3, students continued their interpretations by placing (moving and situating) a wooden number above each column of dinosaurs to identify the quantity in that column, then they compared the quantities concretely and abstractly. From this exercise, they were also offered extension activities to alter the representation and discuss how they reconstructed the graph with different quantities. While the changes they made primarily focused on the number concepts and data analysis, the opportunities to learn and practice SR were implicitly present throughout the project and their associated learning actions.

In subsequent activities, students deconstructed and reconstructed the representation by rearranging the data on the graph to match given numeric scenarios (e.g., five red and four green dinosaurs or seven red and two green). When reorganizing the data into categories, they implicitly experienced opportunities to learn to interpret different configurations. Through this mathematics project, students drew inferences and explained the meaning of the representations of real objects as data they could analyze on the graph, thus experiencing multiple opportunities to learn and practice a variety of SR skills through the existing data analysis mathematics project.

5.1.2. Enactment of Spatial Reasoning in the Mathematics Project

As noted in

Section 5.1, children who engaged in this mathematics project experienced opportunities to learn or practice all six overarching SR skills stipulated in the framework used in this study (see

Table 1;

Pinilla, 2024a). The following examples provide greater detail on how the children enacted

Constructing, Interpreting, and

Situating skills to demonstrate what skills named in the framework would look like in the classroom. Though not exhaustive of skills, the enactments described provide an alternative, and more deductive, lens through which to look for SR learning opportunities.

First, the overarching skill

Constructing is defined as “making or forming a spatial structure by organizing components/parts into a more complex whole” (

Pinilla, 2024a) and includes ideas of

deconstructing by taking the whole apart, plus

reconstructing by putting the structure together in a different form. During this project, children used data (dinosaurs) to create a graph, then de- and re-constructed the graph into new configurations. By first putting the dinosaurs into their color categories, they organized the components into a more complex whole, representing the data as a single graph that they could read. Embedded within this activity was the subskill of

arranging as students placed the objects in relation to one another (i.e., in the “bar” on the graph for the corresponding color) and

rearranged them when prompted to create a new scenario.

Second, the overarching skill

Interpreting is defined as “drawing inferences and/or conclusions by expounding the meaning of problems and representations” (

Pinilla, 2024a), which includes visualizing, seeing patterns, and making sense of mental images.

Interpreting includes

designing, modeling, and

comparing as subskills. When children co-created the wooden graph board with their teacher, they first laid out popsicle sticks on the wooden board to plan and construct a representation of what the graph would look like, thus demonstrating

designing and

modeling skills. They further enacted

modeling skills when they created the real object graph, as arranging them into bars represented the graph itself. Once the graph was created (or recreated when given new scenarios), children

compared the categories on the graph as a form of interpretation. Importantly, in this example, children could count the individual dinosaurs for concrete comparisons of quantities, or they could compare the height of the bars on the graph using the axes. Through their constructing the graph, children experienced numerous opportunities to use multiple

Interpreting skills.

Finally, the overarching skill

Situating is defined as “putting something in or experiencing some place, situation, context, or belongingness to a category” (

Pinilla, 2024a), and includes

intersecting, locating, and

orienting as related subskills. Children enacted these components when creating the graph by

locating the place at which to place each dinosaur based on its belongingness to a color category and

orienting the relations between dinosaurs to fit within the graph (i.e., placing dinosaurs relative to one another instead of putting them on top of other dinosaurs or leaving large gaps). After constructing the graph, students experienced the opportunity to enact

intersecting skills by examining where the height of each bar intersected the y-axis.

5.2. Connecting Spatial Reasoning Teaching Practices and Education Standards

In response to research question 2, we found that the mathematics project incorporated provocation, collaboration, and hands-on activities, which are key characteristics of the RE-IA (

Hachey & Mehta, 2024) that would allow educators ways to create learning environments that can help students develop SR skills in ways aligned with educational standards.

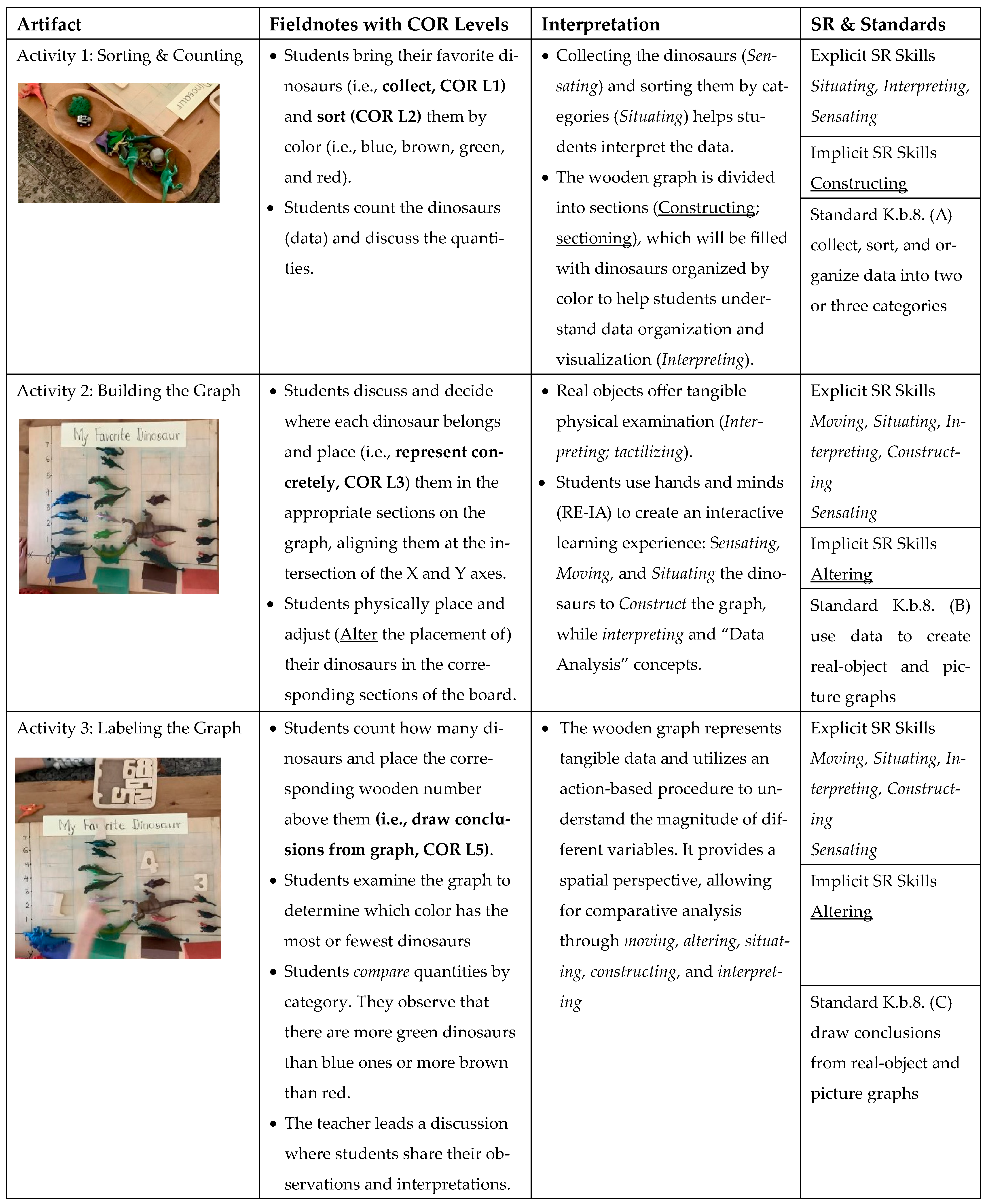

Figure 2 illustrates artifacts and fieldnotes taken during the mathematics project and connects them to the SR skills and one type of related educational standards, the TEKS for kindergarten mathematics. Specifically, mathematics standard K(b)8 states that children should “collect, sort, and organize data into two or three categories” (

Texas Education Agency, 2024, p. 9); within this standard, there are three specific objectives—the right-hand most column of

Figure 2 details which activity is related to which objective. Findings are reported in relation to the TEKS standards, as the COR objectives were known to relate through explicit documentation in the lesson plan (see

Figure 1).

Objective (A) of K(b)8 states that the student will “collect, sort, and organize data into two or three categories” (

Texas Education Agency, 2024, p. 9). As students engaged in Activity 1 (see

Figure 2), they collected the dinosaurs and sorted them by color, which aligns with the objective, and, as stated in findings for RQ1, gave them opportunities to learn or practice SR skills, including

sensating, situating, and

interpreting. In Activity 2, students met Objective (B), which states that students will “use data to create real-object and picture graphs” (

Texas Education Agency, 2024, p. 9), by organizing the dinosaurs on the real-object graph. That activity also provided opportunities to practice the SR skills of

moving and

constructing when creating the real-object graph. The third objective, (C), states that the student will “draw conclusions from real-object and picture graphs” (

Texas Education Agency, 2024, p. 9). The fully constructed graph created in Activity 2 and analyzed in Activity 3 provided children opportunities to draw conclusions about this as a real-object graph and to

interpret what the graph was telling them, both by interacting with, or

sensating, the tactile objects and

interpreting the quantities as abstract representations with associated wooden numerals. Together, these examples demonstrate data analysis concepts specified by TEKS K(b)8 (

Texas Education Agency, 2024) that can be taught and practiced through an integrated mathematics project and offer explicit opportunities to learn and practice SR skills.

6. Discussion

In this paper, we described how a teacher using the RE-IA within their kindergarten classroom provided opportunities for students to learn and practice SR skills through a week-long mathematics project. By using this research as an opportunity to notice the SR occurring in what children were already doing, we found that the skills were present in students’ learning opportunities without changing the teacher’s instructional plans or learning objectives. Additionally, we aligned the learning opportunities with education standards used locally to provide connections to a more typical intended curriculum so that others might adopt these practices. Importantly, this research emerged from the field as responsive to the secondary researcher/teacher and their students to ensure the children had adequate opportunity to learn SR skills—the inquiry met the objective of action research as intending to solve a problem of practice (

Mills, 2014). While many teachers may not have access to professional development that would support their learning to teach SR through mathematics, actively inquiring about their own classroom environment with a specific lens to look for opportunities to learn SR may support their seeing existing activities that support learning and practicing SR and then offering such activities more frequently through what

Lindgren and Schwartz (

2009) called the

noticing effect. That is, if teachers know what SR is and what it looks like, they will be better equipped to give children related learning opportunities.

These findings suggest that by capitalizing on existing classroom activities, teachers can provide opportunities for children to develop SR skills that they might not otherwise have the chance to learn (

Pinilla, 2024b;

Gilligan-Lee et al., 2022). Locally to the U.S., SR is infrequently explicitly referenced in education standards (

Pinilla, 2024b;

Boda et al., 2022;

Gilligan-Lee et al., 2022), thus limiting children’s opportunities to learn the skills through the narrowing of enacted curriculum based on pressure to teach to the test (

Milner, 2014). At the same time, other countries, including some provinces in Canada and European nations, face similar challenges (

Gilligan-Lee et al., 2022). Conversely,

Resnick and Lowrie (

2023) documented how providing learning opportunities to teachers to spatialize their curriculum, which addressed multiple STEM domains, bolstered students’ SR performance, indicating that policy plus professional learning can support SR learning. While we know the importance of SR to academic achievement and STEM career interests (

Duncan et al., 2007;

Wai et al., 2009), the fewer opportunities to learn SR than other mathematics domains is mirrored in U.S. students’ demonstration of SR skills on international assessments, such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (

Sorby & Panther, 2020). To adequately prepare students to be globally competitive in the STEM workforce, children should receive opportunities to learn and practice SR (

Mix & Cheng, 2012;

Sorby & Panther, 2020;

Wai et al., 2009), which, based on this study, can be afforded through the RE-IA.

Additionally, the current lack of SR learning opportunities is a concern of equity, as the linkage between spatial reasoning and mathematics is particularly strong in children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds (

Bower et al., 2020b). While in an Australian context,

Resnick and Lowrie (

2023) found that providing teachers with tools and pedagogical practices that allow them to emphasize SR could be efficacious in providing all children opportunities to learn SR, which highlights a way to tackle current disparities between the mathematical understanding of children with higher and lower socioeconomic statuses (

Bower et al., 2020a). Such changes would require not simply providing another written curriculum, but instead altering the pedagogical view undertaken in schools as related to mathematics and STEAM learning to honor children and their ideas, much as is done in the RE-IA.

By supporting teachers to notice the SR learning opportunities readily available within mathematics projects, the classroom environment, and students’ learning actions, teachers can not only provide opportunities for students to learn these skills critical to STEM and more global academic achievement (

Duncan et al., 2007;

Wai et al., 2009) but also encourage children to explore and manipulate their surroundings to foster a deeper grasp of the physical and temporal world as transdisciplinary spaces (

Freudenthal, 1973;

National Research Council, 2006). Because we know that children enter the classroom with pre-existing mathematical ideas developed through play and daily activities (

Linder et al., 2011;

National Association for the Education of Young Children & National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 2010), we must ensure that their first encounters with formal mathematics and STEAM domain learning emphasize that their conceptions are valid and their curiosities worthwhile; those early mathematics experiences shape children’s mathematical identities as doers of mathematics (

National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 2022;

National Research Council, 2001), and may relate to their holistic STEAM identity development, as well (

Stone, 2022).

Furthermore, by leveraging children’s natural curiosity and innate abilities as learners, teachers can readily cultivate and extend children’s mathematical sense and interest (

National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 2022;

Wien, 2015). The RE-IA achieves this by offering an educational framework focused on children’s interests and abilities through emergent and responsive curricula (

Malaguzzi, 1996), as RE-IA positions teachers, not as givers of dogma, but as facilitators of knowledge. Moreover, this approach gives the freedom necessary for children to explore their environment by treating them as capable of constructing their understandings (

Biermeier, 2015). The exploratory classroom environments fostered within the RE-IA allow children to develop mathematical concepts through real-world, self-directed interactions (

New, 2007), which serves as an approach that may be particularly effective for learning SR.

Limitations, Practical Implications

We identified five specific limitations that may have influenced our findings but could also support the work’s practical implications via transferability. First, the primary and secondary researchers collaborated on a larger project about SR, giving the teacher/secondary researcher a nuanced understanding of SR and how it may appear in the classroom. Without that research experience, they may not have identified the need to enhance their students’ SR learning opportunities as a problem of practice to address through action research. However, SR learning opportunities exist in many early childhood classrooms, and teachers could, with knowledge and planning, connect the skills to their mathematics or other STEAM domain teaching. The presence of unrealized opportunity leads to the practical implication that early childhood educators should be offered professional development that includes information about establishing joyful learning environments, much like those provided in a RE-IA, and how to integrate SR through their mathematics and STEAM teaching practices. Professional learning should be content-focused, of a sustained duration (

Desimone, 2009), and offered within collaborative spaces to ensure that the constructivism described as central to children’s learning is provided to teachers, as well (

Horn & Garner, 2022;

Lave & Wenger, 1991). Studying the work of

Resnick and Lowrie (

2023) to understand how this was done within the ELSA program, or borrowing from practices utilized in the typical curriculum in Canadian early childhood education, as seen in

Hawes et al. (

2017), could provide a starting point for designing context-specific teacher learning opportunities.

Second, the artifacts were collected by the teacher/secondary researcher, were context-specific, and were coded independently using consensus conversations rather than calculations of interrater reliability. These methodological decisions may introduce unintended bias in analysis and reporting. More specifically, if other children were involved in a similar project, the data and subsequent interpretations would likely differ, as this study took place in a single context. However, the thick, rich descriptions and triangulation across sources (

Lincoln & Guba, 1985;

Merriam, 1998) provided in the analyses promote the transferability of findings, which highlights another implication: we need to examine additional cases in traditional early childhood classrooms and programs using other educational models to explore teaching practices and students’ opportunities to learn SR through mathematics or other STEAM content domains. Additionally, examining the variation in children’s enactments of SR in this or a similar activity points to another direction for future research: investigating student learning through the activities instead of just opportunities to learn.

Third, the data display (see

Figure 2) connecting learning activities to standards was presented unidirectionally, moving from artifacts to standards. Whereas some SR learning opportunities were explicit in the project, other skills were represented implicitly in the associated standards, indicating a need for teachers to receive support to integrate SR into learning environments, which harkens back to the first implication of providing teachers with professional learning opportunities. Despite connections identified to teach SR through standards (

Pinilla, 2024b;

Boda et al., 2022), additional research that starts with the standards and locates the SR learning opportunities present should also be documented.

Fourth, and more fundamentally to the structure of early childhood programs, many early childhood-specific schools in the U.S. have attempted to adopt principles of the RE-IA (

Trepanier-Street et al., 2001). There seems to be a sharp divide, however, between the emergent curriculum and encouragement of self-determined expression engendered by Reggio programs and the educational experiences that most children receive. That is, most children, specifically in the U.S., are enrolled in public schools that utilize a written or prescribed curriculum, which is counter to the rich experiences children receive in an RE-IA program. The attempt in this project, then, was to learn if there were benefits to locating SR learning opportunities within a program using a RE-IA to support teachers in taking up such progressive teaching practices in less progressive schooling spaces. While utilizing RE-IA fully may not be feasible, borrowing from research in Australia, we might instead support teachers to provide SR learning opportunities within their curricula (

Resnick & Lowrie, 2023).

Fifth, and finally, the project highlighted in this study was designed to provide opportunities to learn data analysis skills as a mathematical domain. However, to support the teaching and learning of transdisciplinary STEAM, teachers must be intentional about designing learning environments and offering opportunities to learn content that incorporates all or some of the STEM domains (

Moore et al., 2014), plus opportunities for artistic expression that engenders creativity and empowers learners (

Huser, 2020). We understand that the “A” in STEAM is often seen as an add-on (

Perignat & Katz-Buonincontro, 2019), but urge the larger community of educators and education researchers to think of it as a necessary ingredient to supporting student learning and preparation for the challenges of our current and future world (

Huser, 2020).

7. Conclusions

Considering the state of early childhood education as a contentious debate about what is best, and one deeply impacting the lives of adults and children alike (

McCormick Smith & Chao, 2018), this research sheds light on how SR skills can be learned through joyful learning experiences embedded in the curriculum and learning opportunities already present in early childhood classrooms. RE-IA is one approach to teaching early childhood education that can support teaching mathematics, integrated STEM, and transdisciplinary STEAM content to young children through a constructivist orientation, and deserves future research to ascertain how similar experiences might be provided to children writ large rather than being reserved for those whose families can afford specific schooling.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.K.P. and P.J.M.; methodology, R.K.P. and P.J.M.; formal analysis, R.K.P. and P.J.M.; investigation, R.K.P. and P.J.M.; data curation, R.K.P. and P.J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.K.P. and P.J.M.; writing—review and editing, R.K.P., P.J.M., and E.P.S.; supervision, R.K.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Texas at El Paso (2185829-1, 19 April 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of ongoing research. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Code Definitions for Hypothesis and Descriptive Coding by Research Question

| RQ † | Hypothesis Codes * | Descriptive Code |

| 1 | Moving: Changing the position of something by using spatial transformations; examples: balancing, reflecting, rotating, translating. Altering: Modifying or changing something’s appearance (or making something different by modifying in some way by changing what it is); examples: distorting, dilating/contracting, folding, scaling, shearing. Situating: Putting something in or experiencing someplace, situation, context, or belongingness to a category; examples: dimension-shifting, intersecting, locating, orienting, mapping, pathfinding. Constructing: Making or forming a spatial structure by organizing components/parts into a more complex whole; deconstructing: breaking a structure into component parts or elements; reconstructing: reforming/making structure in different configurations; examples: arranging, composing, packing, fitting. Interpreting: Drawing inferences and/or conclusions by expounding the meaning of problems and representations (e.g., map-reading, visualizing, conjuring mental images, or seeing patterns and sense-making based on those interpretations); examples: comparing, designing, diagramming, modeling, relating, symmetrizing. Sensating: Perceiving through the senses; examples: imagining, perspective-taking, projecting, propriocepting, tactilizing, visualizing.

| Active Participation: Exploration through hands-on activities, projects, and group work; gives students autonomy in choosing materials and contributing to project themes and classroom layouts ( Arseven, 2014; Fox, 2023; Martin & Evaldsson, 2012). Communication: Classroom Discussion: Sharing ideas through drawing, puppetry, sculpture, play, and storytelling; children engage in group discourse, listen, express opinions, and build on ideas ( Rinaldi, 2021; Vatalaro et al., 2015). Collaboration: Activities done together (group projects, games, discussions) where children can work communally, share ideas, and learn from each other ( Butvilas & Kołodziejski, 2021; Ganus, 2010; Gillespie, 2000; New, 2007; Parnell, 2011; Smith, 2021; Trepanier-Street et al., 2001). Creativity: Expression through various materials, mediums, and communication forms when given time and space to explore worldly understandings and work collaboratively on projects of interest ( Gandini, 1993; New, 2007; Strong-Wilson & Ellis, 2007). Provocations: Actions by educators to engage children, stimulate curiosity, and encourage them to explore, question, and discover new concepts and ideas through the provision of open-ended materials (e.g., blocks, natural items, art supplies, loose parts) to inspire children to create without predetermined outcomes ( Desouza & Jereb, 2000; Kaynak-Ekici et al., 2021) Hands-on activities: Learning engagements that encourage children to explore materials and concepts through direct interaction that involve multiple senses; gives children freedom to experiment and innovate by using materials in new and creative ways; synonymous with Interactive activities, Experiential learning, Practical exercises, Engaged learning, Active learning, Kinesthetic activities, Tactile experiences, Applied learning, Immersive tasks, Participatory activities, Direct involvement tasks, Fieldwork exercises, Real-world applications, Manipulative tasks, Do-it-yourself (DIY) projects) ( Gillespie, 2000; Martin & Evaldsson, 2012; Swann, 2008).

|

| 2 | TEKS Mathematics

K(b)8: Data analysis. The student applies mathematical process standards to collect and organize data to make it useful for interpreting information. The student is expected to:- (A)

collect, sort, and organize data into two or three categories - (B)

use data to create real-object and picture graphs - (C)

draw conclusions from real-object and picture graphs.

| COR Advantage-Action-oriented Objectives:

Level 1: The child collects objects.

Level 2: The child groups things into two or more collections.

Level 3: The child represents information (data) in concrete ways.

Level 4: The child represents information (data) in abstract ways.

Level 5: The child interprets information (data) from a representation.

Level 6: The child applies information (data) from a representation.

Level 7: The child poses a question of interest and collects and interprets information (data) to figure out the answer. |

Appendix B. Coded Version of a Reggio Emilia-Inspired Kindergarten Lesson Plan

Appendix B.1. Coding Sheet for RQ1

| Component | Lesson Plan | Coder 1 Memo | Coder 2 Memo |

| Introduction | “How Many Dinosaurs?” is a week-long math project designed to engage kindergarten students. It is part of a comprehensive initiative inspired by the Reggio Emilia approach, with the specific goal of introducing and reinforcing data analysis and other essential math concepts, including numbers and operations, patterns, and measurement. The project aims to create an enriching and meaningful learning experience by tapping into the students’ keen interest in dinosaurs. Teacher’s Role: Co-learner, collaborator, facilitator, guide, observer, environment designer, community connector Students’ Role: Active participants, decision-makers, researchers, collaborators, communicators, creative thinkers, problem solvers, observers, reflective learners, environment shapers, community members

| Students’ roles as creative thinkers problem solvers, reflective learners, their creativity and sense of taking mental, physical actions | Student roles support active math and SR learning; what RE-IA characteristics are present in each? |

| Objectives- Mathematics (COR Advantage) | Level 1: The child collects objects.

Level 2: The child groups things into two or more collections.

Level 3: The child represents information (data) in concrete ways.

Level 4: The child represents information (data) in abstract ways.

Level 5: The child interprets information (data) from a representation.

Level 6: The child applies information (data) from a representation.

Level 7: The child poses a question of interest and collects and interprets information (data) to figure out the answer. | COR advantage objectives elaborate TEKS and transform TEKS into doable actions | How do these align with TEKS K.b.8? (a) collect, sort, organize = 1, 2, 3; (b) create graph = 3, 4; (c) draw conclusions = 5, 6, 7 |

| Question of the Day | MON | TUE Can you show me where the line named X is? (locating) (i.e., in the book, on the wooden graph) Can you place the dinosaurs on the graph (translating) based on the colored cards at the bottom? (comparing/relating)

| WED | THUWhich color has the most or fewest dinosaurs (comparing)? Which color dinosaur do you see the most? Which dinosaur is there only a few of? How many dinosaurs are in total?

| FRI

The teacher will instruct students to modify the graph by adjusting the number of dinosaurs, and then students will question their peers: | Actions-oriented questions lead students to give actions-based answers; students talk and act in groups; they use material to give their answers | Explicit SR connections underlined in corresponding color; subskills in parentheses when applicable |

| Provocations | Books: (listed in ELA)

Materials: Wooden board, markers, dinosaurs, rulers, wooden numbers, colored construction paper, scissors, white marker boards, magnetic letters and numbers, puppets, puppet theater | Students use 3D objects, change and modify the graph based on interpretation and analysis | Materials engender tactilizing and moving (SR) |

| ELA | Books: “Graph it! Math it!,” “Graphs; Bar Graphs,” “Show and Tell: Great Graph and Smart Charts” | Tools to lead students to think, interpret and act | |

| Vocabulary | How many, least, most, more, less, graph, axis, count, tally, amount, bar graph, data | Understanding terminology sharpen students’ thinking and analytical skills | Comparing, relating (SR) |

| Mathematics | Definition: Graph: a tool that lets you see how many of those and how many of these.

Description: The graph shows data. On a bar graph, bars represent amounts. Longer bars mean larger amounts and shorter bars mean smaller amounts. Bars help us compare data. | Gives a base for students’ thinking and creativity | Vocab to be used in discussion |

| Large Group | Teacher: places a wooden board in the center of the table for the interactive learning session; gathers students for a collaborative exploration of graphs. Having group reading activities with puppets in puppet theater and using the material, the teacher discusses the fundamental concept of graphs with a question-answer strategy, emphasizing their role in visualizing data. Using the wooden board, the teacher introduces the idea of creating a graph with labeled axes; students propose using different colors and types of dinosaurs as data points. As the discussion unfolds, the students participate in the activity, utilizing thought-provoking material to create a 3D bar graph on the wooden board, making the learning experience an exciting and hands-on endeavor. | Students use material, participate in graph discussion, they move dinosaurs and try to understand what difference it makes | Interactive learning session could also be active participation across all |

Appendix B.2. Coding Key

| Hypothesis Codes | Descriptive Codes |

Moving

Altering

Situating | Constructing

Interpreting

Sensating | Action-provocative-open-ended questions

Active Participation

Communication: Classroom Discussion

Collaboration | Creativity

Hands-on activities

Provocations | |

References

- American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association & the National Council on Measurement in Education. (2014). Standards for educational and psychological testing. American Educational Research Association. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, F. (2019). Social constructivism and action research: Transforming teaching and learning through collaborative practice. In Action research for inclusive education (pp. 5–16). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Arseven, A. (2014). The Reggio Emilia approach and curriculum development process. International Journal of Academic Research, 6(1), 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermeier, M. A. (2015). Inspired by Reggio Emilia: Emergent curriculum in relationship-driven learning environments. Young Children, 70(5), 72–79. [Google Scholar]

- Boda, P. A., James, K., Sotelo, J., McGee, S., & Uttal, D. (2022). Racial and gender disparities in elementary mathematics. School Science and Mathematics, 122(1), 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, C., Odean, R., Verdine, B. N., Medford, J. R., Marzouk, M., Golinkoff, R. M., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2020a). Associations of 3-year-olds’ block-building complexity with later spatial and mathematical skills. Journal of Cognition and Development, 21(3), 383–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, C., Zimmermann, L., Verdine, B., Toub, T. S., Islam, S., Foster, L., Evans, N., Odean, R., Cibischino, A., Pritulsky, C., Hirsh-Pasek, K., & Golinkoff, R. M. (2020b). Piecing together the role of a spatial assembly intervention in preschoolers’ spatial and mathematics learning: Influences of gesture, spatial language, and socioeconomic status. Developmental Psychology, 56(4), 686–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruce, C., Moss, J., & Ross, J. (2012). Survey of JK to grade 2 teachers in Ontario, Canada: Report to the literacy and numeracy secretariat of the ministry of education. Ontario Ministry of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, C. D., Davis, B., Sinclair, N., McGarvey, L., Hallowell, D., Drefs, M., Francis, K., Hawes, Z., Moss, J., Mulligan, J., Okamoto, Y., Whiteley, W., & Woolcott, G. (2017). Understanding gaps in research networks: Using “spatial reasoning” as a window into the importance of networked educational research. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 95, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butvilas, T., & Kołodziejski, M. (2021). Creativity and parental involvement in early childhood education in the Reggio Emilia Approach and philosophy. Edukacja Elementarna w Teorii i Praktyce, 16(61), 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charette, N., Delgado, E., & Kozak, J. (2018). Stop, collaborate, and listen: Reimagining & Rebuilding the Royal Alberta Museum. Museum & Society, 16(3), 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, D. H., & Sarama, J. (2011). Early childhood teacher education: The case of geometry. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 14(2), 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, D. H., Wilson, D. C., & Sarama, J. (2004). Young children’s composition of geometric figures: A learning trajectory. Mathematical Thinking and Learning, 6(2), 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copley, J. V. (2010). The young child and mathematics (2nd ed.). National Association for the Education of Young Children. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., & Guetterman, T. (2019). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (6th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, B., & Spatial Reasoning Study Group (Eds.). (2015). Spatial reasoning in the early years: Principles, assertions, and speculations. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desouza, J. M. S., & Jereb, J. (2000). Gravitating toward Reggio. Science and Children, 37(7), 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, G. J., Dowsett, C. J., Claessens, A., Magnuson, K., Huston, A. C., Klebanov, P., Pagani, L. S., Feinstein, L., Engel, M., Brooks-Gunn, J., Sexton, H., Duckworth, K., & Japel, C. (2007). School readiness and later achievement. Developmental Psychology, 43(6), 1428–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farran, E. K., McCarthy, S., Gilligan-Lee, K. A., Bates, K. E., & Gripton, C. (2024). Translating research to practice: Practitioner use of the spatial reasoning toolkit. Gifted Child Today, 47(3), 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, A. (2023). The Reggio Emilia Approach in the United States [Master’s thesis, Oklahoma State University]. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/reggio-emilia-approach-united-states/docview/2846792082/se-2 (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Fraser, S., & Gestwicki, C. (2002). Authentic childhood: Experiencing Reggio Emilia in the classroom. Delmar. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenthal, H. (1973). Mathematics as an educational task. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandini, L. (1993). Fundamentals of the Reggio Emilia approach to early childhood education. Young Children, 49(1), 4–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ganus, L. A. (2010). The pedagogical role of Reggio-inspired studios in early childhood education [Doctoral dissertation, University of Denver]. Available online: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/224 (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Gattis, M. (2002). Structure mapping in spatial reasoning. Cognitive Development, 17(2), 1157–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, C. W. (2000). Six Head Start classrooms begin to explore the Reggio Emilia approach. Young Children, 55(1), 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan-Lee, K. A., Hawes, Z. C. K., & Mix, K. S. (2022). Spatial thinking as the missing piece in mathematics curricula. NPJ Science Learning, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachey, A. C., & Mehta, P. J. (2024). The iSTEM Rope Model: Defining integrated early childhood STEM education and its pedagogical linages to the Reggio Emilia-Inspired Approach. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, D. (2021). Spatial ability, skills, reasoning or thinking: What does it mean for mathematics? Mathematics Education Research Group of Australasia. [Google Scholar]

- Hawes, Z., & Ansari, D. (2020). What explains the relationship between spatial and mathematical skills? A review of evidence from brain and behavior. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 27(3), 465–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, Z., Moss, J., Caswell, B., Naqvi, S., & MacKinnon, S. (2017). Enhancing children’s spatial and numerical skills through a dynamic spatial approach to early geometry instruction: Effects of a 32-week intervention. Cognition and Instruction, 35(3), 236–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HighScope. (2013). HighScope resource for educators. Available online: https://highscope.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Winter2013_150.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Horn, I., & Garner, B. (2022). Teacher learning of ambitious and equitable mathematics instruction: A sociocultural approach. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huser, J. (2020). STEAM and the role of the arts in STEM (pp. 4–20). State Education Agency Directors of Arts Education. Available online: https://www.nationalartsstandards.org/sites/default/files/SEADAE-STEAM-WHITEPAPER-2020.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Ishikawa, T., & Newcombe, N. S. (2021). Why spatial is special in education, learning, and everyday activities. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 6(1), 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaynak-Ekici, K. B., İmir, H. M., & Temel, Z. F. (2021). Learning invitations in Reggio Emilia approach: A case study. Education 3–13, 49(6), 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C. (2023). Documenting children’s spatial reasoning through art: A case study on play-based STEAM education. Sustainability, 15(19), 14051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Linder, S. M., Powers-Costello, B., & Stegelin, D. A. (2011). Mathematics in early childhood: Research-based rationale and practical strategies. Early Childhood Education Journal, 39(1), 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, R., & Schwartz, D. A. (2009). Spatial learning and computer simulations in science. International Journal of Science Education, 31(3), 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linn, M. C., & Petersen, A. C. (1985). Emergence and characterization of sex differences in spatial ability: A meta-analysis. Child Development, 56(6), 1479–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, S., & Donahue, D. M. (2009). Reggio-Inspired professional development in a diverse urban public school: Cases of what is possible. Teacher Development, 13(2), 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaguzzi, L. (1996). The hundred languages of children: The Reggio Emilia approach to early childhood education. Ablex Publishing Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, C., & Evaldsson, A. C. (2012). Affordances for participation: Children’s appropriation of rules in a Reggio Emilia school. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 19(1), 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick Smith, M., & Chao, T. (2018). Critical science and mathematics early childhood education: Theorizing Reggio, play, and critical pedagogy into an actionable cycle. Education Sciences, 8(4), 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, M. G. (1979). Human spatial abilities: Sources of sex differences. Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education: Revised and expanded from case study research in education. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, G. E. (2014). Action research: A guide for the teacher researcher (5th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Milner, H. R., IV. (2014). Scripted and narrowed curriculum reform in urban schools. Urban Education, 49(7), 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mix, K. S., & Cheng, Y. L. (2012). The relation between space and math: Developmental and educational implications. Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 42, 197–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, A., & Mohan, L. (2014). Spatial thinking through the elementary years. Social Studies Review, 53, 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, C. G. (2013). Theories of childhood: An introduction to Dewey, Montessori, Erikson, Piaget & Vygotsky (2nd ed.). Redleaf Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, T. J., Glancy, A. W., Tank, K. M., Kersten, J. A., & Smith, K. A. (2014). A framework for quality K-12 engineering education: Research and development. Journal of Pre-college Engineering Education Research, 4(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, J., Hawes, Z., Naqvi, S., & Caswell, B. (2015). Adapting Japanese lesson study to enhance the teaching and learning of geometry and spatial reasoning in early years classrooms: A case study. ZDM, 47(3), 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, J. (2015). Looking within and beyond the geometry curriculum: Connecting spatial reasoning to mathematics learning. ZDM Mathematics Education, 47(3), 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, J., Woolcott, G., Mitchelmore, M., & Davis, B. (2018). Connecting mathematics learning through spatial reasoning. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 30(1), 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Association for the Education of Young Children & National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. (2010). Early childhood mathematics: Promoting good beginnings: A joint position statement of the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) and the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM), adopted in 2002, updated in 2010. National Association for the Education of Young Children. Available online: https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/resources/position-statements/psmath.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. (2022). Mathematics in early childhood learning: A position of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. Available online: https://www.nctm.org/Standards-and-Positions/Position-Statements/Mathematics-in-Early-Childhood-Learning/ (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, Council of Chief State School Officers. (2010). Common core state standards. Available online: http://corestandards.org/ (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- National Research Council. (2001). Adding it up: Helping children learn mathematics. The National Academies Press. [CrossRef]

- National Research Council. (2006). Learning to think spatially. National Academies Press. [CrossRef]

- New, R. S. (2007). Reggio Emilia as cultural activity theory in practice. Theory into Practice, 46(1), 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnell, W. (2011). Revealing the experience of children and teachers even in their absence: Documenting in the early childhood studio. Journal of Early Childhood Research: ECR, 9(3), 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perignat, E., & Katz-Buonincontro, J. (2019). STEAM in practice and research: An integrative literature review. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 31, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinilla, R. K. (2024a). Defining spatial reasoning: A content analysis to explicate spatial reasoning skills for early childhood educators’ use. Journal of Research in Science, Mathematics and Technology Education, 7(SI), 141–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinilla, R. K. (2024b). Spatial reasoning in mathematics standards: Identifying how early elementary educators are systematically supported to teach spatial skills. Frontiers in Education, Teacher Education Section, 9, 1407388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, I., & Lowrie, T. (2023). Spatial reasoning supports preschool numeracy: Findings from a large-scale nationally representative randomized control trial. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 54(5), 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, C. (2021). Dialogue with Reggio Emilia: Listening, researching and learning (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]