Exploring Pre-Service Teachers’ Self-Efficacy: The Impact of Community of Practice and Lesson Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Self-Efficacy (SE)

2.2. Community of Practice (CoP) and Lesson Study (LS)

2.2.1. Community of Practice (CoP): A Collaborative Learning Space

2.2.2. Lesson Study (LS): Deep Learning Through Practice

- Collaborative Planning—Teachers work together to set learning objectives, design learning activities, and create instructional materials (Fernandez & Yoshida, 2004).

- Teaching and Observation—One teacher teaches the collaboratively planned lesson while colleagues observe the students’ learning behaviors and classroom interactions in detail.

- Reflection and Discussion—After the lesson, the teaching and observing teachers engage in structured reflection to discuss strengths, weaknesses, and possible improvements.

- Revision and Re-teaching (if necessary)—Feedback from the reflection session is used to revise the lesson plan, which may then be re-taught to test its improved effectiveness.

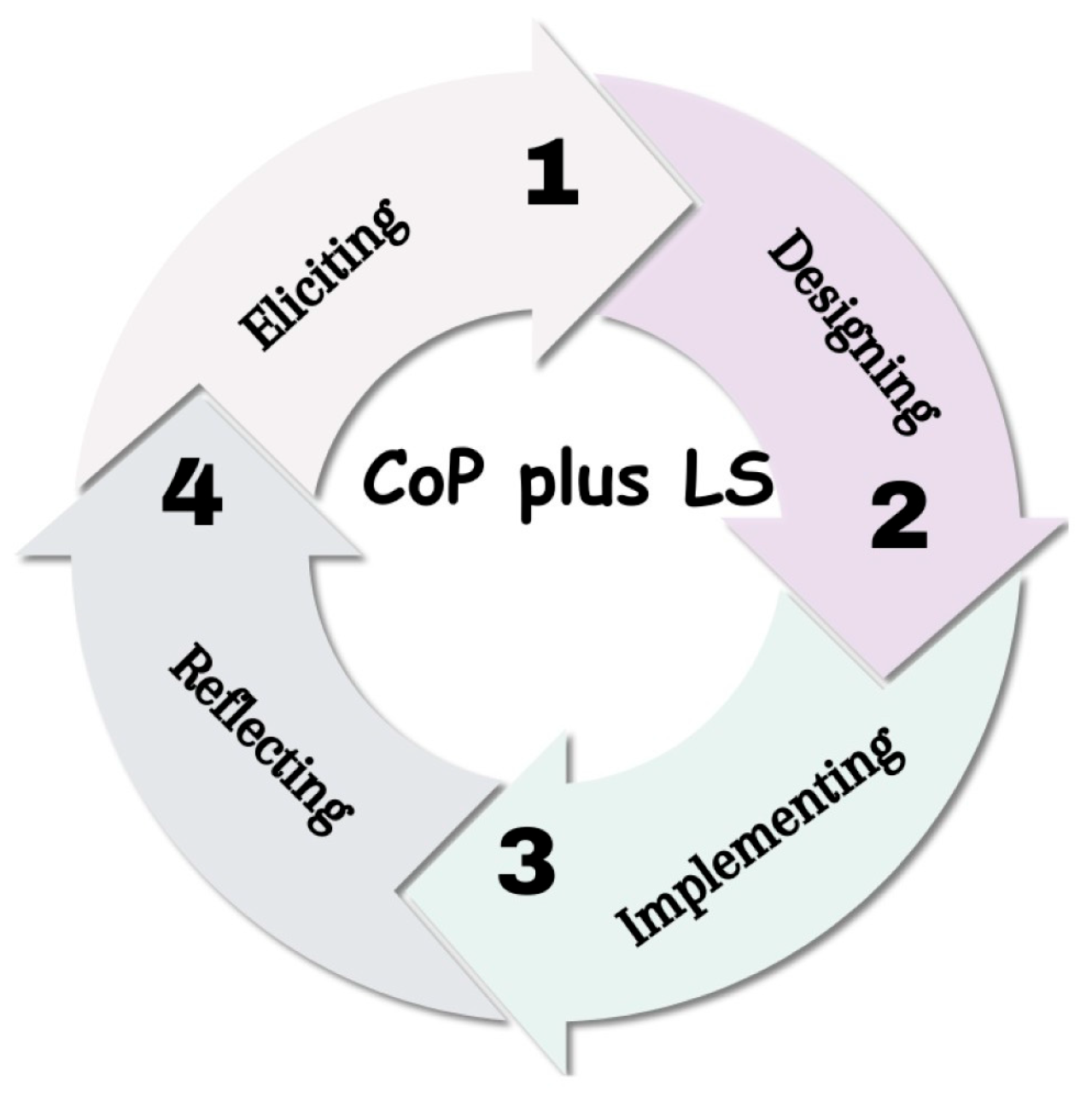

2.2.3. Integrating CoP and LS: A Transformative Force in Teacher Professional Development

- Eliciting—Forming groups of student teachers within the same school context who share similar teaching challenges. These groups share knowledge, experiences, and effective teaching techniques.

- Designing—Collaboratively designing lesson plans and learning activities through group discussions and the exchange of ideas.

- Implementing—Teachers implement the collaboratively designed activities in their classrooms, while peers observe and document teaching practices.

- Reflecting—Groups engage in critical reflection, analyzing teaching outcomes and refining their activities to enhance effectiveness.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Participants

3.3. Research Instruments

3.4. Data Collection

- Eliciting: Pre-service teachers collaborated to establish learning goals and identify problems for classroom action research. They engaged in joint study, discussion, and knowledge sharing related to classroom research.

- Designing: The pre-service teachers co-designed learning activities and research procedures, drafted research proposals, and developed research instruments collaboratively.

- Implementing: The pre-service teachers applied their planned instructional activities and research tools in their own classrooms, with peer pre-service teachers providing classroom observation and support.

- Reflecting: The CoP group reconvened to reflect on the teaching outcomes and research findings, engaged in collaborative critique, and jointly prepared the research report. The process concluded with the formulation of shared best practices.

3.5. Data Analysis

- (1)

- The pre-service teachers in the conventional learning group, and the pre-service teachers in the CoP plus LS group, were compared with the Mann–Whitney U-test to determine if SE differed. The Mann–Whitney U-test is appropriate for comparing differences in central tendency between two independent groups when the outcomes are not normally distributed. Additionally, effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated to assess the practical significance of differences.

- (2)

- The pre-service teachers who participated in the CoP plus LS had outcomes measured three times—pre-intervention, post-intervention, and an 8-week follow-up. To determine if the mean ranks differed among the repeated measures, the Friedman Test was used. When significant differences occurred, to determine which time points differed statistically, pairwise comparisons with the Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test were conducted.

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CoP | Community of Practice |

| LS | Lesson Study |

| SE | Self-Efficacy |

References

- Baker, A. T., & Beames, S. (2016). Good CoP: What makes a community of practice successful? Journal of Learning Design, 9(1), 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Betoret, F. D. (2006). Stressors, self-efficacy, coping resources, and burnout among secondary school teachers in Spain. Educational Psychology, 26(4), 519–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boud, D., Keogh, R., & Walker, D. (2013). Reflection: Turning experience into learning. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cajkler, W., Wood, P., Norton, J., & Pedder, D. (2014). Lesson study as a vehicle for collaborative teacher learning in a secondary school. Professional Development in Education, 40(4), 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, D., & Wong, H. W. (2002). Measuring teacher beliefs about alternative curriculum designs. Curriculum Journal, 13(2), 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M. H., & Rathbun, G. (2013). Implementing teacher-centred online teacher professional development (oTPD) programme in higher education: A case study. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 50(2), 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojorn, K., & Seesom, C. (2024). Enhancing pre-service teachers’ TPACK through the integrating of community of practice and lesson study. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE), 13(6), 4237–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojorn, K., & Sonsupap, K. (2022). Investigating student teachers’ reflections on early field experiences. Journal of Educational Issues, 8(1), 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojorn, K., & Sonsupap, K. (2023). An activity for building teaching potential designed on community of practice cooperated with lesson study. Journal of Curriculum and Teaching, 12(4), 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, G. R., Auhl, G., & Hastings, W. (2013). Collaborative feedback and reflection for professional growth: Preparing first-year pre-service teachers for participation in the community of practice. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 41(2), 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Learning Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dede, C. (2010). Comparing frameworks for 21st century skills. In J. Bellance, & R. Brandt (Eds.), 21st century skills rethinking how students learn (pp. 51–76). Solution Tree Press. [Google Scholar]

- Desimone, L. M. (2011). A primer on effective professional development. Phi Delta Kappan, 92(6), 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doig, B., & Groves, S. (2011). Japanese lesson study: Teacher professional development through communities of inquiry. Mathematics Teacher Education and Development, 13(1), 77–93. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, P. (2013). Teacher learning in lesson study: What interaction-level discourse analysis revealed about how teachers utilised imagination, tacit knowledge of teaching and fresh evidence of pupils learning, to develop practice knowledge and so enhance their pupils’ learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 34, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, P. L., Hao, Y., Iverson, E., & Macdonald, R. H. (2022). Fostering communities of practice among community college science faculty. Community College Review, 50(4), 391–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C., & Yoshida, M. (2004). Lesson study a Japanese approach to improving mathematics teaching and learning. Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, M. (2016). The new meaning of educational change (5th ed.). Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison, D. R., & Kanuka, H. (2004). Blended learning: Uncovering its transformative potential in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 7(2), 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guskey, T. R. (2002). Professional development and teacher change. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 8(3), 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefetz, G., & Ben-Zvi, D. (2020). How do communities of practice transform their practices? Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 26, 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiebert, J., Gallimore, R., & Stigler, J. W. (2002). A knowledge base for the teaching profession: What would it look like and how can we get one? Educational Researcher, 31(5), 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, A. W., & Spero, R. B. (2005). Changes in teacher efficacy during the early years of teaching: A comparison of four measures. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21(4), 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R. M., & Chiu, M. M. (2010). Effects on teachers’ self-efficacy and job satisfaction: Teacher gender, years of experience, and job stress. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(3), 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korthagen, F. (2017). Inconvenient truths about teacher learning: Towards professional development 3.0. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 23(4), 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C. (2002). Lesson study A handbook of teacher-led instructional change. Research for Better Schools. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, C., Perry, R., & Murata, A. (2006). How should research contribute to instructional improvement? The case of lesson study. Educational Researcher, 35(3), 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J., & Mercieca, B. M. (2021). What is a community of practice? In Sustaining communities of practice with early career teachers. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R. F., & Baki, M. (2013). The effectiveness of online and blended learning: A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Teachers College Record, 115(3), 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. (1997). Transformative learning: Theory to practice. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 1997(74), 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizell, H. (2010). Why professional development matters. Learning Forward. [Google Scholar]

- Panadero, E. (2017). A review of self-regulated learning: Six models and four directions for research. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, K., & Parker, M. (2017). Teacher education communities of practice: More than a culture of collaboration. Teaching and Teacher Education, 67, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants part 1. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipper, T., Goei, S. L., de Vries, S., & van Veen, K. (2018). Developing teachers’ self-efficacy and adaptive teaching behaviour through lesson study. International Journal of Educational Research, 88, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D. A. (2017). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. In The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D. H., & Greene, J. A. (2017). Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance, second edition. In Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance (2nd ed.). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D. H., & Zimmerman, B. J. (2007). Influencing children’s self-efficacy and self-regulation of reading and writing through modeling. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 23(1), 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, K. (2016). The fourth industrial revolution. World Economic Forum. [Google Scholar]

- Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism a learning theory for the digital age. International Journal of Instructional Technology & Distance Learning, 2(1), 1–9. Available online: http://www.itdl.org/Journal/Jan_05/article01.htm (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2007). Dimensions of teacher self-efficacy and relations with strain factors, perceived collective teacher efficacy, and teacher burnout. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(3), 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonsupap, K., & Cojorn, K. (2024). A collaborative professional development and its impact on teachers’ ability to foster higher order thinking. Journal of Education and Learning (EduLearn), 18(2), 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigler, J. W., & Hiebert, J. (1999). The teaching gap Best ideas from the world’s teachers for improving in the classroom. The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stoll, L., Bolam, R., McMahon, A., Wallace, M., & Thomas, S. (2006). Professional learning communities: A review of the literature. Journal of Educational Change, 7(4), 221–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 783–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangrieken, K., Dochy, F., & Raes, E. (2016). Team learning in teacher teams: Team entitativity as a bridge between teams-in-theory and teams-in-practice. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 31(3), 275–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangrieken, K., Meredith, C., Packer, T., & Kyndt, E. (2017). Teacher communities as a context for professional development: A systematic review. Teaching and Teacher Education, 61, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrieling, E., Bastiaens, T., & Stijnen, S. (2012). Effects of increased self-regulated learning opportunities on student teachers’ motivation and use of metacognitive skills. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 37(8), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, E., McDermott, R., & Snyder, W. M. (2002). A guide to managing knowledge cultivating communities of practice. Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H., & Pedder, D. (2014). Lesson study: An international review of research. In P. Dudley (Ed.), Lesson study: Professional learning for our time (pp. 29–59). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, H., & Shinmachi, Y. (1999). The influence of instructional intervention on children’s understanding of fractions. Japanese Psychological Research, 41(4), 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zee, M., & Koomen, H. M. Y. (2016). Teacher self-efficacy and its effects on classroom processes, student academic adjustment, and teacher well-being: A synthesis of 40 years of research. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 981–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(2), 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Self-Efficacy | Total | Conventional | CoP Plus LS | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Test | Post-Test | Pre-Test | Post-Test | ||||||||||

| Mean | S.D. | Level | Mean | S.D. | Level | Mean | S.D. | Level | Mean | S.D. | Level | ||

| Student Engagement | 9 | 5.63 | 0.92 | Mo. | 6.46 | 1.06 | Mo. | 5.86 | 0.71 | Mo. | 6.71 | 0.81 | Mo. |

| Instructional Strategies | 9 | 6.38 | 0.82 | Mo. | 6.63 | 1.20 | Mo. | 5.79 | 0.74 | Mo. | 7.04 | 1.23 | Hi. |

| Classroom Management | 9 | 6.25 | 0.85 | Mo. | 6.89 | 1.07 | Mo. | 5.57 | 0.74 | Mo. | 7.07 | 1.02 | Hi. |

| Overall | 9 | 6.08 | 0.91 | Mo. | 6.60 | 0.99 | Mo. | 5.73 | 0.73 | Mo. | 6.93 | 1.04 | Mo. |

| Intervention | N | Mean Rank | Sum of Ranks | U | W | Z | p | Cohen’s d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | Conventional | 6 | 8.58 | 51.50 | 11.50 | 39.50 | −1.38 | 0.166 | - |

| CoP plus LS | 7 | 5.64 | 39.50 | ||||||

| Post-test | Conventional | 6 | 4.58 | 27.50 | 6.50 | 27.50 | −2.10 | 0.036 * | 0.33 |

| CoP plus LS | 7 | 9.07 | 63.50 |

| Intervention | N | Mean Rank | df | χ2 | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Test | Post-Test | Follow-Up | |||||

| CoP plus LS | 7 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 2 | 14.00 | 0.001 * |

| Comparison | N | Mean Rank | Sum of Ranks | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest-Posttest | 7 | −4.00 | −28.00 | −2.371 | 0.018 * |

| Pretest-Follow-up | 7 | −4.00 | −28.00 | −2.375 | 0.018 * |

| Post test-Follow-up | 7 | 4.00 | 28.00 | −2.401 | 0.016 * |

| Theme | Category | Subcategory | Example Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-Efficacy | Confidence in instructional management |

| “At first, I didn’t dare to discipline the students, but as I got to know them better, I became more comfortable giving instructions and speaking up.” “The students were quiet and didn’t respond at first, so I tried using simpler questions. Once they started answering, I became much more confident.” “At the beginning, I was afraid of making mistakes while teaching, but after several lessons, I felt that my communication improved, and the students started to respond better.” |

| Appropriate activity design |

| “When I realized that students did not like lectures, I adapted my teaching by incorporating games and more visuals. This increased their interest, and I felt more confident in my teaching.” “Initially, I taught through lectures, but when students showed little interest, I shifted to group activities, which encouraged greater student participation.” “Sometimes I use Kahoot, which excites the students and made me understand the importance of finding ways to make lessons enjoyable.” “At first, when I lectured, students rarely responded. Then, I tried pairing them to exchange ideas, and this increased their engagement.” “I always design activities with embedded games because they keep students alert and facilitate learning.” “Occasionally, I use Kahoot to review lessons, and students find it more enjoyable and participatory than traditional Q&A sessions.” | |

| Classroom management |

| “In some classrooms, I have to use a firm tone because students talk too much. Without controlling it, the class becomes disorderly.” “When students are inattentive, I stop and look at them, then ask their names. This makes them aware that I am watching.” “I set rules with the students from the first day, such as raising hands to ask questions, and they gradually understand the classroom norms.” | |

| 2. Professional Passion & Identity | Experiencing a sense of pride and accomplishment |

| “A student thanked me for tutoring and said they passed the exam. I felt very happy and thought the effort was worthwhile.” “When students ask me additional questions after class, I feel they value my teaching, which reassures me that I’m on the right track.” “I feel encouraged when a student says, ‘I understand because the teacher explains clearly.’” |

| Commitment to the teaching profession | Perseverance in pursuing a teaching career despite challenges | “Some days are very tiring, but I still don’t want to change careers. I enjoy being with the students.” “Even though I’m very tired, the more I teach, the more confident I become that I truly want to be a teacher.” “Before the practicum, I thought teaching would be exhausting, but after experiencing it, despite the fatigue, I feel it is meaningful.” | |

| 3. Classroom Reality Challenges | Discrepancies between theory and practice | Differences between learned concepts and real-world situations | “Some students are very attentive, while others are stubborn and refuse to comply, so different motivation techniques are necessary.” “Most of what I learned focused on lesson planning, but in reality, students don’t always listen, so quick adjustments are essential.” “During teaching practice, I realized that nothing goes exactly as planned; everything must be adaptable at all times.” |

| Learner diversity | Diverse student needs require continuous adaptation | “Some students learn quickly, while others are much slower, so I prepare two levels of worksheets for them to choose from.” “Some classrooms are very quiet, others are very noisy; I have to use different approaches even when teaching the same content.” “Despite thorough preparation, when students are inattentive, I feel discouraged and have cried alone in the teacher’s lounge.” “Some classes go well, while others are disruptive; I need to adjust my lesson plans to fit the students.” | |

| Expectations from mentor teachers and school context | Pressure from the role of a full-fledged teacher | “The mentor teacher wanted me to start teaching right away, but the students were uncooperative, so I was very stressed at first.” “The mentor expected me to be able to do everything. I felt a lot of pressure and had to train myself a lot.” “Sometimes the mentor teacher criticized me harshly, but when I thought about it later, it was true and something I needed to fix.” | |

| 4. Collaborative Reflection and Co-Learning | Learning from peers and mentors |

| “After teaching, my mentor teacher discusses what went well and what needs improvement. I take notes and apply them in the next lesson.” “My peers in the practicum observe my teaching and provide feedback on what worked and what should be adjusted. I find this very helpful.” “Sometimes, just talking with others who face the same challenges makes me feel less alone.” |

| Professional growth through situational learning |

| “My development is shown in my ability to adapt to different students; I realize that one method cannot work for all.” “At first, I was hesitant to teach and discipline students, but now I feel much more confident.” | |

| Peer reflection within the Community of Practice (CoP) |

| “During meetings with peers in the CoP, I observed different problem-solving approaches and tried applying them myself.” “Regular discussions within the CoP group made me feel supported, knowing I’m not solving problems alone and have multiple strategies to try.” “After teaching observations, peers in the group collaboratively provide feedback, and I have adjusted my methods based on their suggestions several times.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sonsupap, K.; Cojorn, K.; Choompunuch, B.; Intakanok, C.; Seesom, C. Exploring Pre-Service Teachers’ Self-Efficacy: The Impact of Community of Practice and Lesson Study. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101357

Sonsupap K, Cojorn K, Choompunuch B, Intakanok C, Seesom C. Exploring Pre-Service Teachers’ Self-Efficacy: The Impact of Community of Practice and Lesson Study. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101357

Chicago/Turabian StyleSonsupap, Kanyarat, Kanyarat Cojorn, Bovornpot Choompunuch, Chanat Intakanok, and Chaweewan Seesom. 2025. "Exploring Pre-Service Teachers’ Self-Efficacy: The Impact of Community of Practice and Lesson Study" Education Sciences 15, no. 10: 1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101357

APA StyleSonsupap, K., Cojorn, K., Choompunuch, B., Intakanok, C., & Seesom, C. (2025). Exploring Pre-Service Teachers’ Self-Efficacy: The Impact of Community of Practice and Lesson Study. Education Sciences, 15(10), 1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101357