Resilience Profiles of Teachers: Associations with Psychological Characteristics and Demographic Variables

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Teacher Psychological Resilience

1.2. Teacher Resilience and Self-Efficacy

1.3. Teacher Resilience and Burnout

1.4. Teacher Resilience and Meaning in Life

1.5. Teacher Resilience and Emotional Intelligence

1.6. Resilience in Relation to Demographics

1.7. Aims and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.1.1. Study 1

2.1.2. Study 2

2.2. Research Instruments

2.2.1. Teachers’ Protective Factors of Resilience Scale—Studies 1 and 2

2.2.2. Meaning in Life Questionnaire—Study 1

2.2.3. Schutte Self-Report Emotional Intelligence Test—Study 1

2.2.4. Maslach Burnout Inventory—Study 2

2.2.5. Teachers’ Sense of Efficacy Scale—Study 2

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Means, Standard Deviations, Skewness, and Kurtosis of the Variables

3.2. Resilience Profiles

3.3. Differences in Resilience Profiles in Relation to Meaning in Life, Emotional Intelligence, Burnout, and Self-Efficacy

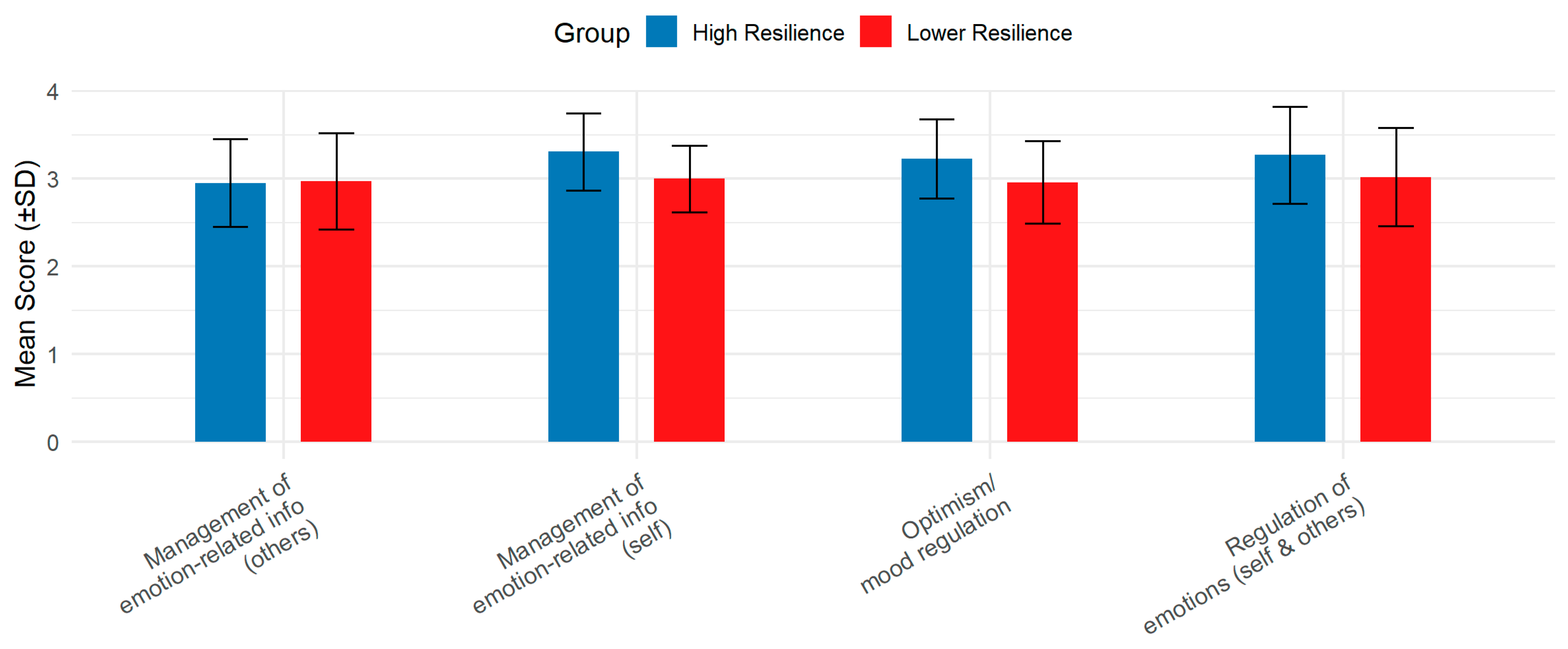

3.3.1. Study 1

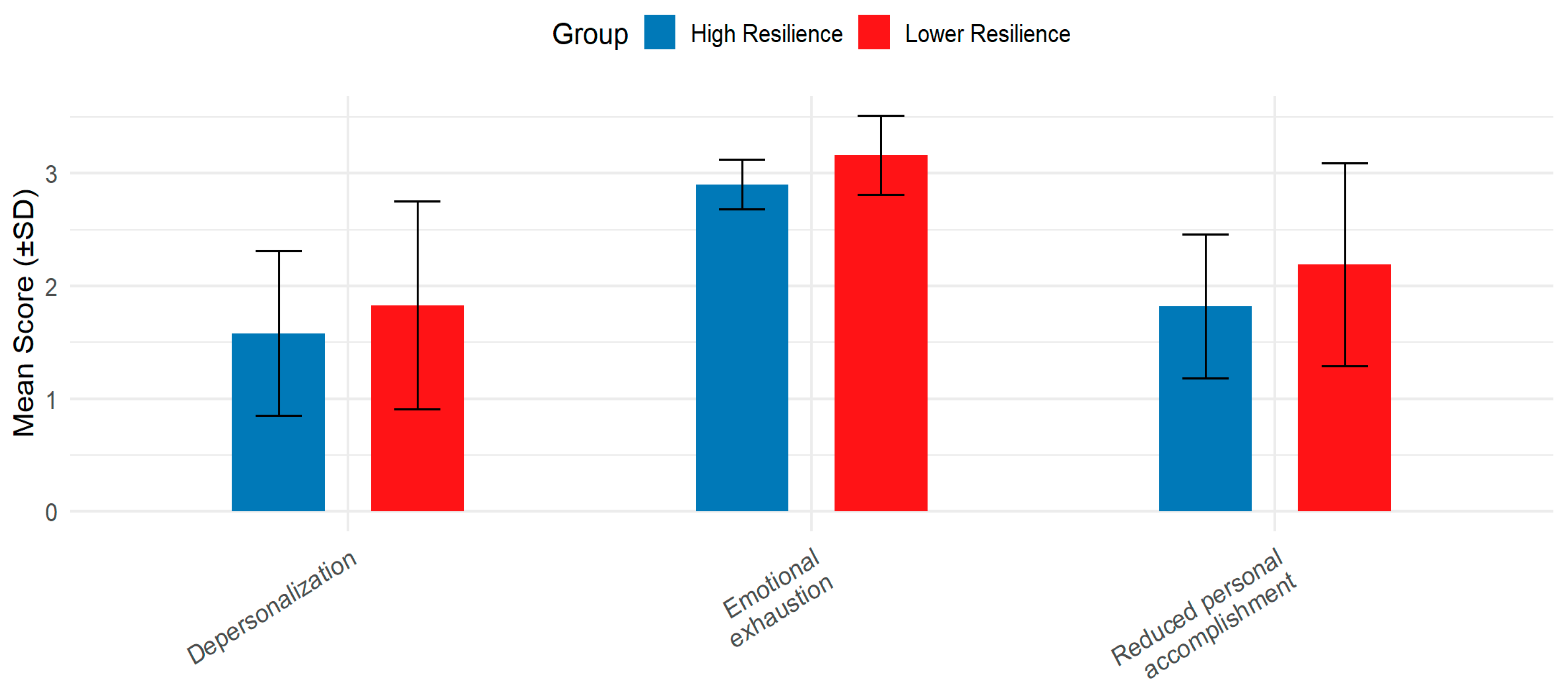

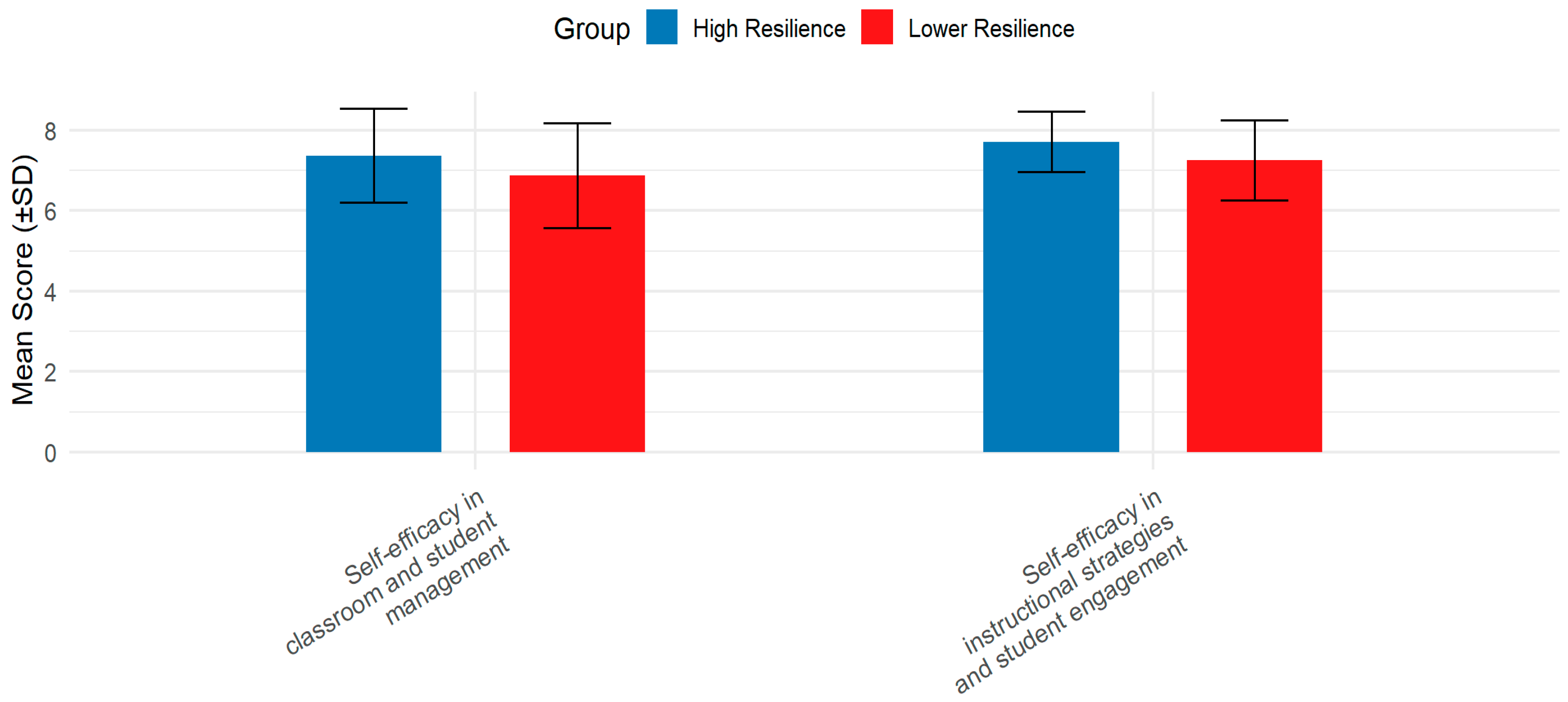

3.3.2. Study 2

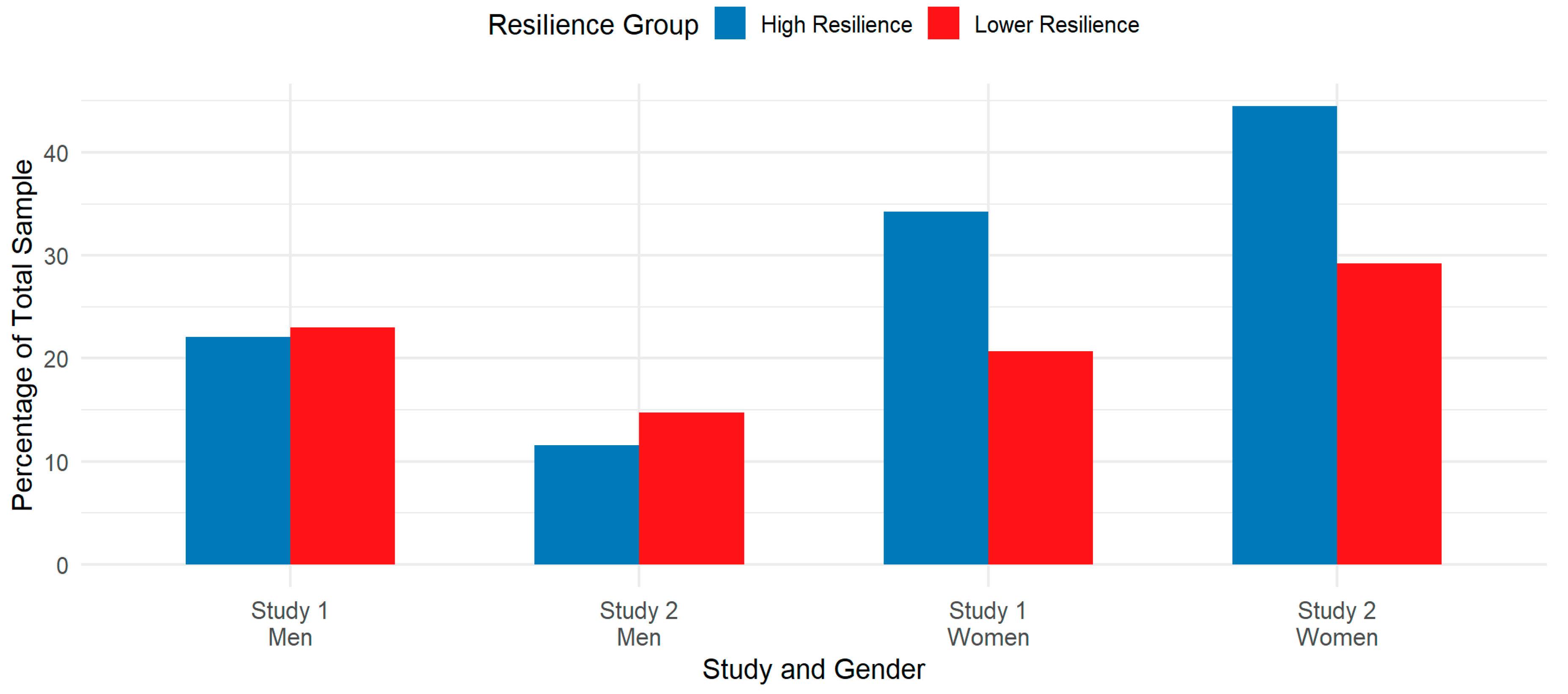

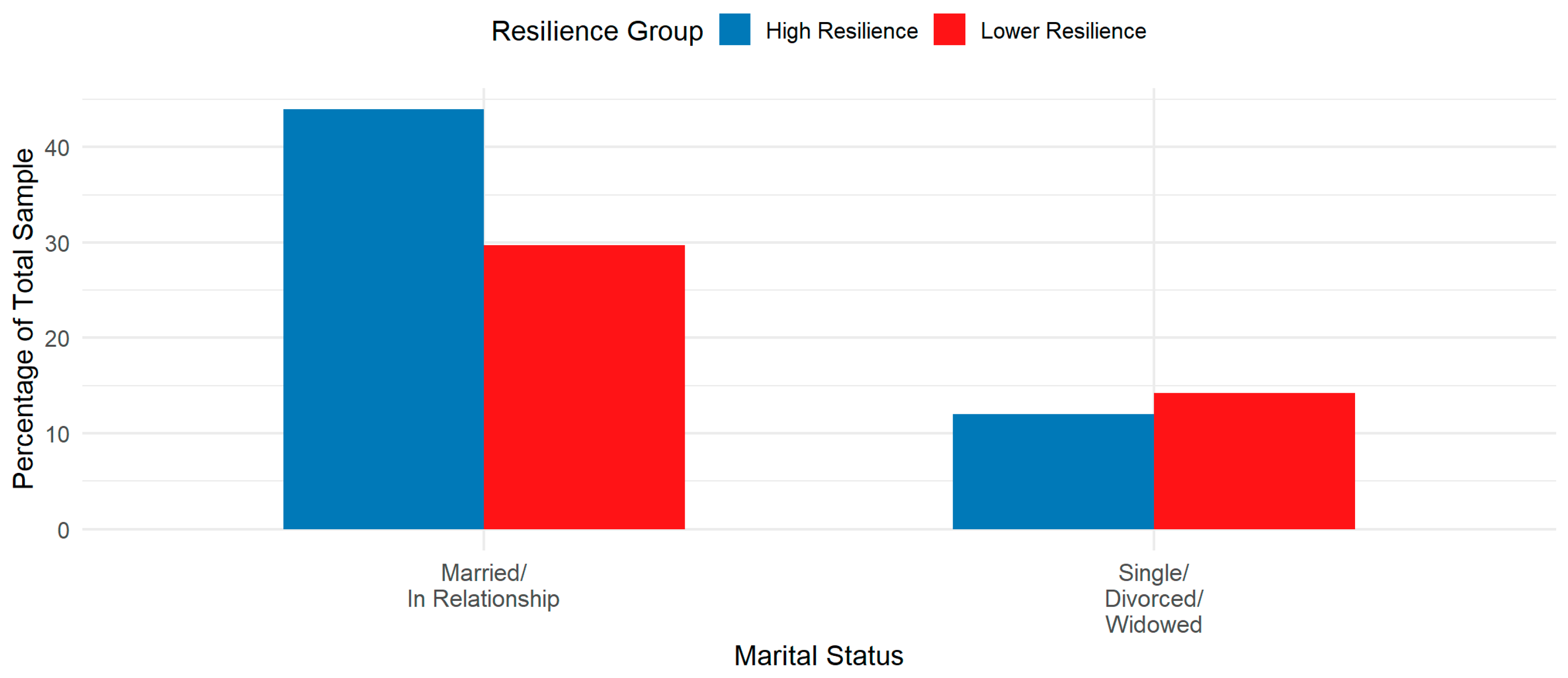

3.4. Differences in Resilience Profiles in Relation to Demographics

3.4.1. Study 1

3.4.2. Study 2

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for the Teaching Profession

4.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Afiah, N., Fakhruddin, Z., & Samaun, S. S. (2024). Resilience in teaching: Uncovering grit differences based on marital status in madrasah English teachers. Journal An-Nafs: Kajian Penelitian Psikologi, 9(2), 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyapong, B., Obuobi-Donkor, G., Burback, L., & Wei, Y. (2022). Stress, burnout, anxiety and depression among teachers: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainsworth, S., & Oldfield, J. (2019). Quantifying teacher resilience: Context matters. Teaching and Teacher Education, 82, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L., & Olsen, B. (2006). Investigating early career urban teachers’ perspectives on and experiences in professional development. Journal of Teacher Education, 57(4), 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnová, S., Vochozka, M., Krásna, S., Gabrhelová, G., & Barna, D. (2024). Gender differences and stereotypes in teacher resilience research. Emerging Science Journal, 8, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltman, S. (2021). Understanding and examining teacher resilience from multiple perspectives. In C. F. Mansfield (Ed.), Cultivating teacher resilience (pp. 11–26). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltman, S., Mansfield, C. F., & Price, A. (2011). Thriving not just surviving: A review of research on teacher resilience. Educational Research Review, 6, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boczkowska, M., Daniilidou, A., & Platsidou, M. (2024). A preliminary comparison study of teachers’ resilience in Greece and Poland. Psychology in the Schools, 61(5), 1808–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botou, A., Mylonakou-Keke, I., Kalouri, O., & Tsergas, N. (2017). Primary school teachers’ resilience during the economic crisis in Greece. Psychology, 8(1), 131–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouskeli, V., Kaltsi, V., & Loumakou, M. (2018). Resilience and occupational well-being of secondary education teachers in Greece. Issues in Educational Research, 28(1), 43–60. Available online: http://www.iier.org.au/iier28/brouskeli.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Chu, W., & Liu, H. (2022). A mixed-methods study on senior high school EFL teacher resilience in China. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 865599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantine, E., Mwinjuma, J. S., & Nemes, J. (2025). Assessing the influence of socio-demographic characteristics on teachers’ resilience in Tanzania: A study of selected secondary schools in Morogoro Municipality. Educational Dimension, 12, 186–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniilidou, A. (2023). Risk and protective factors and coping strategies for building resilience in Greek general and special education teachers. Journal of School and Educational Psychology, 3(2), 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniilidou, A., Kyriakidou-Rasidaki, M., & Nerantzaki, K. (2024). Factors influencing special education career choices: Interplay of personality traits and identity statuses. European Journal of Educational Research, 13(4), 1587–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniilidou, A., & Platsidou, M. (2022). Development and testing of a scale for assessing the protective factors of teachers’ resilience. Psychology: The Journal of the Hellenic Psychological Society, 27(3), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniilidou, A., Platsidou, M., & Gonida, E. (2020). Primary school teachers’ resilience: Association with teacher self-efficacy, burnout and stress. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 18(3), 549–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 49(3), 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delle Fave, A., Brdar, I., Freire, T., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Wissing, M. P. (2011). The eudaimonic and hedonic components of happiness: Qualitative and quantitative findings. Social Indicators Research, 100, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q., Zheng, B., & Chen, J. (2020). The relationship between personality traits, resilience, school support, and creative teaching in higher school physical education teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 568906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vera García, M. I. V. (2020). Resilient keys to burnout prevention in high school teachers. Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science, 3(2), 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, S. V., & Sosnowski, C. (2019). Emerging theory of teacher resilience: A situational analysis. English Teaching: Practice & Critique, 18(4), 492–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L., Ma, F., Liu, Y. M., Liu, T., Guo, L., & Wang, L. N. (2021). Risk factors and resilience strategies: Voices from Chinese novice foreign language teachers. Frontiers in Education, 5, 565722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, M. A. (2020). Surviving, being resilient and resisting: Teachers’ experiences in adverse times. Cambridge Journal of Education, 50(2), 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q. (2018). (Re)conceptualising teacher resilience: A social-ecological approach to understanding teachers’ professional worlds. In M. Wosnitza, F. Peixoto, S. Beltman, & C. Mansfield (Eds.), Resilience in education—Concepts, contexts and connections (pp. 13–33). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halchenko, M., Malynoshevska, A., Belska, N., & Melnyk, M. (2024). Resilience of teachers, students, and their parents under the conditions of martial law. School Psychology, 39(2), 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y., & Wang, Y. (2021). Investigating the correlation among Chinese EFL teachers’ self-efficacy, work engagement, and reflection. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 763234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hascher, T., Beltman, S., & Mansfield, C. (2021). Teacher wellbeing and resilience: Towards an integrative model. Educational Research, 63(4), 416–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikotun, A. M., Ezugwu, A. E., Abualigah, L., Abuhaija, B., & Heming, J. (2023). K-means clustering algorithms: A comprehensive review, variants analysis, and advances in the era of big data. Information Sciences, 622, 178–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, K. P., & Garg, P. (2021). Teachers’ psychological well-being role of emotional intelligence and resilient character traits in determining the psychological well-being of Indian school teachers. International Journal of Educational Management, 35(4), 768–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M. N., & Adam, S. B. (2023). A structural equation modeling analysis of the relationships between perceived occupational stress, burnout, and teacher resilience. Second Language Teacher Education, 2(1), 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavgaci, H. (2022). The relationship between psychological resilience, teachers’ self-efficacy and attitudes towards teaching profession: A path analysis. International Journal of Progressive Education, 18(3), 278–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, C. M. (2006). Factor structure and psychometric properties of the maslach burnout inventory—Educators survey among elementary and secondary school teachers in Cyprus. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 22(1), 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaridou, A. (2019). Exploring the values of educators in Greek schools. Research in Educational Administration and Leadership, 4(2), 231–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroux, M., & Théorêt, M. (2014). Intriguing empirical relations between teachers’ resilience and reflection on practice. Reflective Practice, 15(3), 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Huang, L., & Liu, X. P. (2023). Primary school teacher’s emotion regulation: Impact on occupational well-being, job burnout, and resilience. Psychology in the Schools, 60(10), 4089–4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. (2023). The effect of teacher self-efficacy, teacher resilience, and emotion regulation on teacher burnout: A mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1185079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Liu, B., & Zhou, X. (2024). Exploring the mediating role of EFL teachers’ emotion regulation in the relationship between emotional intelligence and resilience. International Journal of Applied Linguistics. Ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Zhao, L., & Su, Y. S. (2022). The impact of teacher competence in online teaching on perceived online learning outcomes during the COVID-19 outbreak: A moderated-mediation model of teacher resilience and age. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 6282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohbeck, L. (2018). The interplay between the motivation to teach and resilience of student teachers and trainee teachers. In M. Wosnitza, F. Peixoto, S. Beltman, & C. Mansfield (Eds.), Resilience in education: Concepts, contexts and connections (pp. 93–106). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- López-Angulo, Y., Mella-Norambuena, J., Sáez-Delgado, F., Portillo Peñuelas, S. A., & Reynoso González, O. U. (2022). Association between teachers’ resilience and emotional intelligence during the COVID-19 outbreak. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 54, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, C. F., Beltman, S., Broadley, T., & Weatherby-Fell, N. (2016). Building resilience in teacher education: An evidenced informed framework. Teaching and Teacher Education, 54, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, C. F., Beltman, S., Price, A., & McConney, A. (2012). “Don’t sweat the small stuff”: Understanding teacher resilience at the chalkface. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(3), 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1986). Maslach burnout inventory manual (2nd ed.). Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C., & Schaufeli, W. B. (1993). Historical and conceptual development of burnout. In W. B. Schaufeli, C. Maslach, & T. Marek (Eds.), Professional burnout: Recent developments in theory and research. Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsopoulos, A., Griva, A. M., Psinas, P., & Monasterioti, I. (2019). Teachers’ perceptions of teacher evaluation, professional identities and educational institutions: An analysis based on the symbolic universes approach. In S. Salvatore, V. Fini, T. Mannarini, J. Valsiner, & G. Veltri (Eds.), Symbolic universes in time of (post) crisis: The future of European societies (pp. 191–214). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., & Caruso, D. R. (2004). Target articles: Emotional intelligence: Theory, findings, and implications. Psychological Inquiry, 15(3), 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, M., & Cao, R. (2024). Mutually beneficial relationship between meaning in life and resilience. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 58, 101409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Lucas, J., Luis, J., Rodríguez, M., & Manuel, F. (2023). Stress, burnout, and resilience: Are teachers at risk? International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 25(2), 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papatraianou, L. H., & Le Cornu, R. (2014). Problematising the role of personal and professional relationships in early career teacher resilience. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 39(1), 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, F., Wosnitza, M., Pipa, J., Morgan, M., & Cefai, C. (2018). A multidimensional view on pre-service teacher resilience in Germany, Ireland, Malta and Portugal. In M. Wosnitza, F. Peixoto, S. Beltman, & C. Mansfield (Eds.), Resilience in education: Concepts, contexts and connections (pp. 73–89). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezirkianidis, C., Galanakis, M., Karakasidou, I., & Stalikas, A. (2016). Validation of the meaning in life questionnaire (MLQ) in a Greek sample. Psychology, 7, 1518–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platsidou, M. (2010). Trait emotional intelligence of Greek special education teachers in relation to burnout and job satisfaction. School Psychology International, 31(1), 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platsidou, M., & Daniilidou, A. (2021). Meaning in life and resilience among teachers. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 5(2), 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, D. D., & İskender, M. (2018). Exploring teachers’ resilience in relation to job satisfaction, burnout, organizational commitment and perception of organizational climate. International Journal of Psychology and Educational Studies, 5(3), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, H., Karakose, T., Ozdemir, T. Y., Tülübaş, T., Yirci, R., & Demirkol, M. (2023). An examination of the relationships between psychological resilience, organizational ostracism, and burnout in K–12 teachers through structural equation modelling. Behavioral Sciences, 13(2), 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo-Rico, T., Poveda, R., Gutiérrez-Fresneda, R., Castejón, J. L., & Gilar-Corbi, R. (2023). Revamping teacher training for challenging times: Teachers’ well-being, resilience, emotional intelligence, and innovative methodologies as key teaching competencies. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 16, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, K. A. R., Levesque-Bristol, C., Templin, T. J., & Graber, K. C. (2016). The impact of resilience on role stressors and burnout in elementary and secondary teachers. Social Psychology of Education, 19, 511–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, G. E. (2002). The metatheory of resilience and resiliency. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(3), 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarakinioti, A., & Tsatsaroni, A. (2015). European education policy initiatives and teacher education curriculum reforms in Greece. Education Inquiry, 6(3), 28421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, T. (2021). The psychology of meaning in life. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Schutte, N. S., Malouff, J. M., Hall, L. E., Haggerty, D. J., Cooper, J. T., Golden, C. J., & Dornheim, L. (1998). Development and validation of a measure of emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 25(2), 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R., & Greenglass, E. (1999). Teacher burnout from a social-cognitive perspective: A theoretical position paper. In R. Vandenberghe, & A. M. Huberman (Eds.), Understanding and preventing teacher burnout: A sourcebook of international research and practice (pp. 238–246). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M. F., Kashdan, T. B., Sullivan, B. A., & Lorentz, D. (2008). Understanding the search for meaning in life: Personality, cognitive style, and the dynamic between seeking and experiencing meaning. Journal of Personality, 76(2), 199–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C., Zhuang, L., Xiao, W., Li, X., & Sun, B. (2025). Teacher professional identity on teacher empathy: The moderating roles of competence and growth values and ego-resilience. Psychology in the Schools, 62(5), 1530–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllou, K. (2020). Centralized and decentralized educational systems: A comparative quantitative approach. International Journal of Educational Innovation, 2(6), 112–123. [Google Scholar]

- Tschannen-Moran, M., Hoy, A. W., & Hoy, W. K. (1998). Teacher efficacy: Its meaning and measure. Review of Educational Research, 68(2), 202–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17, 783–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsigilis, N., Grammatikopoulos, V., & Koustelios, A. (2007). Applicability of the teachers’ sense of efficacy scale to educators teaching innovative programs. International Journal of Educational Management, 21(7), 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wingerden, J., & Poell, R. F. (2019). Meaningful work and resilience among teachers: The mediating role of work engagement and job crafting. PLoS ONE, 14(9), e0222518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesely-Maillefer, A. K., & Saklofske, D. H. (2018). Emotional intelligence and the next generation of teachers. In K. V. Keefer, J. D. A. Parker, & D. H. Saklofske (Eds.), Emotional intelligence in education: Integrating research with practice (pp. 377–402). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Gao, Y., Wang, Q., & Zhang, P. (2024). Relationships between self-efficacy and teachers’ well-being in middle school English teachers: The mediating role of teaching satisfaction and resilience. Behavioral Sciences, 14(8), 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, F., Li, X., Song, X., & Zhu, L. (2020). The underlying mechanisms of psychological resilience on emotional experience: Attention-bias or emotion disengagement. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., & Luo, Y. (2023). Review on the conceptual framework of teacher resilience. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1179984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhi, R., & Derakhshan, A. (2024). Modelling the interplay between resilience, emotion regulation and psychological well-being among Chinese English language teachers: The mediating role of self-efficacy beliefs. European Journal of Education, 59(3), e12643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study 1 | Study 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

| Resilience 1 | ||||||||

| Values and beliefs | 4.06 | 0.679 | −0.890 | 1.374 | 3.99 | 0.784 | −1.048 | 1.642 |

| Relationships outside school | 3.36 | 0.804 | −0.295 | −0.530 | 3.48 | 0.998 | −0.426 | −0.592 |

| Legislative framework | 3.86 | 0.802 | −0.557 | 0.217 | 3.70 | 0.838 | −0.547 | 0.227 |

| Emotional and behavioral competence | 4.02 | 0.546 | −0.199 | −0.408 | 4.27 | 0.511 | −0.654 | 0.432 |

| Relationships in school | 3.37 | 0.688 | −0.082 | −0.149 | 3.53 | 0.690 | −0.404 | −0.081 |

| Physical well-being | 3.38 | 0.964 | −0.369 | −0.501 | 3.66 | 0.856 | −0.593 | 0.223 |

| Meaning in life 2 | ||||||||

| Presence of meaning | 5.77 | 0.944 | 1.051 | 1.277 | ||||

| Search for meaning | 5.26 | 1.263 | −0.938 | 0.985 | ||||

| Emotional intelligence 1 | ||||||||

| Optimism/mood regulation | 3.11 | 0.484 | −0.686 | 0.839 | ||||

| Management of emotion-related information concerning the self | 3.18 | 0.446 | −0.620 | 1.102 | ||||

| Management of emotion-related information concerning others | 2.87 | 0.532 | −0.366 | 0.421 | ||||

| Regulation of emotions of self and others | 3.16 | 0.571 | −0.703 | 0.690 | ||||

| Burnout 2 | ||||||||

| Emotional exhaustion | 3.21 | 1.287 | 0.795 | −0.070 | ||||

| Reduced personal accomplishment | 1.98 | 0.792 | 1.249 | 1.846 | ||||

| Depersonalization | 1.69 | 0.834 | 1.906 | 1.559 | ||||

| Self-efficacy 3 | ||||||||

| Classroom and student management | 7.15 | 1.251 | −1.156 | 1.876 | ||||

| Instructional strategies and student engagement | 7.51 | 0.902 | −0.978 | 1.572 | ||||

| Study 1 | Study 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Cluster 1 High Resilience (N = 125) | Cluster 2 Lower Resilience (N = 97) | F (1, 221) | Cluster 1 High Resilience (N = 228) | Cluster 2 Lower Resilience (N = 179) | F (1, 405) |

| Values and beliefs | 4.39 | 3.64 | 94.427 ** | 4.28 | 3.64 | 79.506 ** |

| Relationships outside school | 3.67 | 2.99 | 47.402 ** | 4.03 | 2.80 | 245.713 ** |

| Legislative framework | 4.19 | 3.44 | 59.890 ** | 4.05 | 3.26 | 115.947 ** |

| Emotional and behavioral competence | 4.32 | 3.64 | 130.717 ** | 4.47 | 4.02 | 99.514 ** |

| Relationships in school | 3.68 | 2.98 | 75.744 ** | 3.82 | 3.17 | 114.199 ** |

| Physical well-being | 3.98 | 2.62 | 214.435 ** | 3.98 | 3.28 | 81.188 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daniilidou, A.; Platsidou, M.; Stafylidis, A.; Stafylidis, S. Resilience Profiles of Teachers: Associations with Psychological Characteristics and Demographic Variables. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1358. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101358

Daniilidou A, Platsidou M, Stafylidis A, Stafylidis S. Resilience Profiles of Teachers: Associations with Psychological Characteristics and Demographic Variables. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1358. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101358

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaniilidou, Athena, Maria Platsidou, Andreas Stafylidis, and Savvas Stafylidis. 2025. "Resilience Profiles of Teachers: Associations with Psychological Characteristics and Demographic Variables" Education Sciences 15, no. 10: 1358. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101358

APA StyleDaniilidou, A., Platsidou, M., Stafylidis, A., & Stafylidis, S. (2025). Resilience Profiles of Teachers: Associations with Psychological Characteristics and Demographic Variables. Education Sciences, 15(10), 1358. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101358