1. Introduction

Higher Education Institutions (HEIs), also referred to as agents of change or catalysts for addressing sustainability issues (

Žalėnienė & Pereira, 2021), play an essential role in fostering transformative societal change, particularly through their missions and activities that contribute to the advancement of a more sustainable future (

Caeiro & Azeiteiro, 2020). Education for sustainable development in HEIs aims to provide learners with the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values necessary to make informed decisions and take responsible actions that promote environmental, economic and social sustainability (

Tafese & Kopp, 2025).

Over 600 HEIs have formally committed to sustainability, yet many face challenges in operationalizing these principles due to limited institutional prioritization, resources, and staff engagement (

Leal Filho et al., 2023;

Machado & Davim, 2023). Despite these constraints, sustainability research in HEIs is well supported in several European countries, notably Spain, Germany, Sweden, and Portugal (

Tafese & Kopp, 2025). For instance, HEIs have increasingly integrated sustainability into their systemic programs, although efforts have predominantly focused on environmental and economic dimensions, with comparatively limited attention to social sustainability (

Gamage et al., 2022;

Tafese & Kopp, 2025). This imbalance may stem from the challenges in evaluating the outcomes of social initiatives, managing inequality, and the complexity of advocacy efforts (

Ankareddy et al., 2025), as well as from difficulties in defining and measuring social sustainability in HE settings (

Larrán Jorge et al., 2018).

In Europe, the operationalization of social sustainability in HE is shaped by the commitment to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (

de la Calle et al., 2021). According to

Claeys-Kulik et al. (

2019), frameworks like the European Education Area and the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) reveal that social cohesion, equity, and inclusivity are key components of HE performance and long-term resilience. In Western Europe, diversity and inclusion initiatives, performance indicators that specifically encompass equity metrics, and targeted funding for underrepresented groups are frequently used for social sustainability (

Bhopal, 2018;

Vukasović & Stensaker, 2017), while in Northern Europe, social sustainability is reflected in social cohesion, trust, and institutional legitimacy (

Jónsson et al., 2024). In Eastern Europe, social sustainability is becoming more prevalent, but it is not regularly incorporated into educational frameworks (

Curaj et al., 2020;

Stăiculescu et al., 2022;

Rocchi et al., 2022).

Romania is one of the Eastern European countries which presents a very low level of sustainable education (

Rocchi et al., 2022), and top Romanian HEIs are still raising awareness about the concept (

Șimon et al., 2020). Examining the evolution of sustainability and, especially, social sustainability in Romanian HEIs provides insights on how they develop and implement the principles of social sustainability under constrained conditions and structural barriers such as regional disparities in educational access, student disengagement, and the underrepresentation of vulnerable groups (

Santa & Fierăscu, 2022;

Ionașcu & Pînzariu, 2023;

Voicu & Muntean, 2023).

Broadly, social sustainability is defined as education that fosters a just, equitable society, where all individuals can participate fully in social and democratic life (

Wolff & Ehrström, 2020). In HEIs, social sustainability may be considered a utopia, which needs strong principle guidelines to make HE genuinely transformative (

Wolff & Ehrström, 2020;

Barnett-Itzhaki et al., 2025;

Ankareddy et al., 2025). Social sustainability in HEIs may be embedded across curricula and operations and in specific activities about justice, equity, inclusion, social cohesion, democracy, safety, and well-being (

Barnett-Itzhaki et al., 2025).

Although social sustainability in HEIs is complex and confusing due to its value-laden and content-dependent nature (

Wolff & Ehrström, 2020;

Ankareddy et al., 2025), it is necessary that all stakeholders of an HEI, particularly staff, faculty, students, government, employers, suppliers and community, are involved for the transformative change to occur and to ensure the relevance of the sustainable initiatives (

Leal Filho et al., 2019;

Shih et al., 2025).

Students are a central stakeholder group in HEIs, not only due to their numerical significance and role in institutional academic activities, but also because of their willingness to engage in sustainable practices (

Boarin et al., 2020). Students are recognized as active agents of change in universities, as their perspectives critically shape the effectiveness of these efforts (

Leal Filho et al., 2023;

Machado & Davim, 2023). However, the students’ effective participation can be limited by insufficient understanding of the concept of social sustainability (

Zeegers & Clark, 2014) and by the perceptions that social sustainability is secondary to their academic and operational priorities (

Shih et al., 2025). Promoting awareness on how HEIs contribute to societal well-being has been shown to increase student engagement and their contributions to sustainability (

Maiorescu et al., 2020). At an operational level, these contributions may work as feedback loops (

H. Young & Jerome, 2020). For instance, student advocacy for inclusive measures, mental health resources, and student participatory governance often make HEIs introduce peer mentoring programs, advisory councils, or improve accessibility initiatives (

Hudler et al., 2019;

Slimmen et al., 2025), embedding social sustainability principles into their institutional culture (

Basheer et al., 2025). At the societal level, students who experience cohesive and inclusive HEI environments are more likely to rely on these values in their professional activities, promoting broader initiatives of social responsibilities, connected to diversity, inclusion, social justice, and disability rights (

Hudler et al., 2019). As examples of good practices of European Universities initiatives in contributing to a more social sustainable society,

Arnaldo Valdés and Gómez Comendador (

2022) selected the EELISA HEI Alliance, which aimed to create communities that would solve social challenges by acknowledging the engagement (attitude and implication) of a student, his/her participation within the EELISA community, as well as his/her contribution to the process of solving social challenges. Another example selected by the same authors is the YUFE Alliance, which consists of a Student Forum, with the aim of ensuring that student’s perspective is always taken into consideration during the implementation stage of the initiative. Therefore, the assessment and implementation of socially sustainable initiatives in HEIs, can address the systematic problems of students across all facets of the institutions (

Leal Filho et al., 2023).

A comprehensive evaluation of sustainability integration in HEIs requires assessment tools that encompass both academic and administrative metrics (

Barnett-Itzhaki et al., 2025). In the absence of standardized tools and frameworks, HEIs often face difficulties in measuring the effectiveness of their sustainability initiatives and in identifying the dimensions that need improvement (

Umar et al., 2024), in this case, social sustainability. A large proportion of HEIs have, to some degree, implemented sustainability frameworks (

Ramirez-Montoya et al., 2024) and assessed the effectiveness of sustainability based on them. The most widely endorsed sustainability frameworks in HEIs include The Sustainability Tracking, Assessment and Rating System, the Campus Environmental Audit Response Form, The Sustainability Assessment Questionnaire, and the College Sustainability Report Card (

Gamage et al., 2022). Yet, their focus remains uneven, with an emphasis on environmental and economic performance, with unclear assessment of social sustainability in HEIs (

Machado & Davim, 2023) or the social sustainability is assessed with a mixture of items about education, research, operations, and community engagement (

Aleixo et al., 2018).

This lack of conceptual clarity of social sustainability in HEIs draws attention to the need for more comprehensive approaches that move beyond fragmented or indirect measures (

Machado & Davim, 2023;

Barnett-Itzhaki et al., 2025). In this regard, the social sustainability framework developed by

Ballon and Cuesta (

2024), which encompasses inclusion, resilience, social cohesion, and process legitimacy, offers an important theoretical foundation. In this context, it may be assumed that HEIs may operate as dynamic social systems in which social cohesion, inclusion, and HEI resilience, collectively shape students’ perceptions of social sustainability in an HEI, and are reflected in their academic satisfaction lives.

Social cohesion refers to the strength of relationships and the sense of solidarity among community members (

Fonseca et al., 2019). Social cohesion in an HEI refers to the degree to which students feel a part of the larger academic and social community, as well as the level of interactions with other students, teachers, and administrative personnel. According to

Zhang and Qian (

2024), students are more likely to have a sense of commitment to their academic goals and a sense of belonging when they perceive a strong and supportive network of peers and personnel in their HEI.

Inclusion in an HEI is reflected in ensuring equal opportunities for engagement in academic and social life, irrespective of socioeconomic background, ethnicity, gender, or ability of students or personnel (

Tinto, 2017;

Altes et al., 2024). It has been demonstrated that inclusive practices, such as equitable resource distribution, inclusive teaching, and focused assistance for underrepresented groups of students, increase their satisfaction and retention (

Thai & Alang, 2024).

Organizational resilience is the ability of an institution to adjust and prosper in the face of instability, uncertainty, and change (

Duchek, 2020). This refers to HEIs being able to respond to crises or unstable periods and adjusting to long-term issues like financial constraints, and digital transformation (

Rapanta et al., 2020;

Gligorea et al., 2022). For students, HEI resilience is experienced through the stability and accessibility of learning opportunities, the continuity of academic programs and inclusive learning environment, and adaptable support systems during times of uncertainty (

de Oliveira Durso et al., 2021;

Hassan et al., 2024).

Student satisfaction with academic life may be a result of social sustainability initiatives. It shows how well students’ expectations and experiences align with their expectations across peer relationships, support services, teaching quality, and the overall environment in an HEI (

Gruber et al., 2010).

Collectively, the fragmented nature of existing social sustainability initiatives reflects an ongoing global shift toward embedding it in HEIs’ structures and cultures (

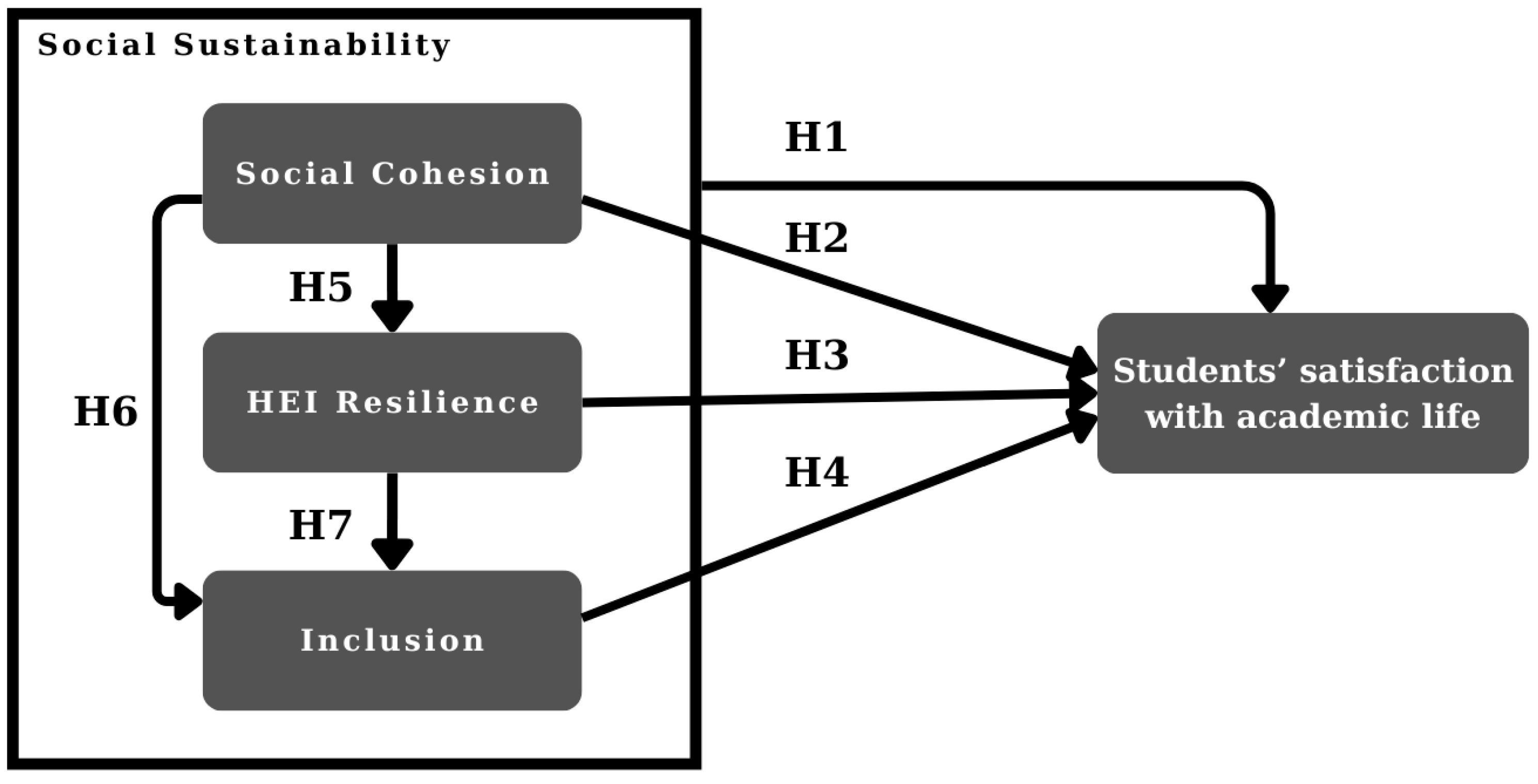

Annarelli et al., 2024). Yet, research assessing social sustainability from students‘ perspectives, using an instrument for examining the effectiveness of social sustainability in HEIs, remains limited, particularly in contexts with constrained conditions. This study aims to address these gaps by investigating the extent to which social cohesion, inclusion, and HEI resilience—recognized as key components of social sustainability—predict Romanian students’ perceived satisfaction with their academic experiences.

The specific objectives of the study are: (1) to elaborate a comprehensive measurement instrument for assessing social sustainability in a Romanian HEI; (2) to evaluate the perceptions of the students regarding the implementation of overall social sustainability and on its components in a Romanian HEI.

5. Discussion

This study extends the theoretical understanding of social sustainability in HE by developing an integrated framework, as being perceived by undergraduate students. While prior research on social sustainability analyzed it as a secondary objective of transnational HE alliances (

Arnaldo Valdés & Gómez Comendador, 2022) or as an example of a living lab environment, where students, faculty, and staff collaborate on real-world challenges (

Purcell et al., 2019), this study assesses the effectiveness of social sustainability in an HEI from the perspective of students and in association with their academic satisfaction. Moreover, this study uses an integrated framework which consists of three components- social cohesion, inclusion and HEI resilience. In doing so, it integrates constructs into a second-order model, which in the literature were studied in isolation, and it provides new insights into the theoretical topic of student satisfaction in sustainable universities.

Firstly, the findings emphasize that social cohesion was the strongest predictor of students’ academic satisfaction. Although there was a moderate association, the result is consistent with previous research and contributes to the development of theory by extending the understanding of social cohesion beyond social integration. The present finding aligns with the existing literature, which suggests that supportive peer networks, trust, and shared values are fundamental drivers of positive academic experiences (

Poole et al., 2023), while research by

Hussain et al. (

2025) emphasizes the established relationship between social cohesion and students’ overall academic performance and emotional health. The study indicated that students who are socially engaged are less likely to feel isolated and more likely to succeed academically (

Hussain et al., 2025). In the same vein,

Rehman et al. (

2024) asserted that social cohesion is closely linked to students’ sense of belonging and identity, both being important for academic success. Also, a sense of belonging has been demonstrated to enhance students’ emotional well-being, thereby encouraging active participation in academic and extracurricular activities (

Gheorghe et al., 2024). This, in turn, serves to reinforce their satisfaction with academic life.

Secondly, the role of inclusion in predicting students’ academic satisfaction was moderate but extends the existing inclusion theories in HE. Although the concept of inclusion has been extensively researched in the context of equity and diversity, there is a limited body of literature that has examined its association with student satisfaction. The findings of the present study revealed that from students’ perspectives, inclusive practices are a measurable dimension of organizational effectiveness (

Shore et al., 2010;

C. Wilson & Secker, 2015), and implicitly, of social sustainability in HEIs. If students perceive a high sense of welcome and support, they will have an increased level of academic satisfaction (

Sakız & Jencius, 2024).

Thirdly, while HEI resilience emerged as a predictor of students’ academic satisfaction, this relationship was small, which was in accordance with the existing literature, especially the one which focuses on COVID-19 and academic activities. Although students’ perceived HEI resilience may contribute to their satisfaction with academic life, the small established relationship suggests that resilience is one of many factors of satisfaction and it often acts in the background. For many students, more immediate academic activities are important in shaping their satisfaction. From a social sustainability perspective, these activities may be reflected in responsive teaching environments, active learning methodologies, and the existence of supportive faculty departments and structures (

M. R. Young et al., 2023;

Cai & Meng, 2025). Furthermore, HEI resilience may buffer negative experiences or crises but might not be visible in everyday aspects of academic life, unless those crises are present.

Moreover, the findings revealed that social cohesion can also be a predictor for HEI resilience and inclusion. However, these associations are small because social cohesion may act as a context and not be defined by concrete initiatives. For instance, social cohesion refers to feelings of trust, belonging and shared values among peers or community, but these do not always transform into concrete inclusive behaviors or HEI resilience policies (

Manitsa et al., 2023). It is asserted that inclusion initiatives may exist in formal structures, but their effectiveness is amplified only when there are strong social ties and a sense of belonging (

C. Wilson & Secker, 2015). Similarly, in resilience research, social cohesion does contribute to community or HEI resilience during times of crises, otherwise is more diffused.

Moreover, the present study revealed that HEI resilience may be a significant predictor of inclusion, but with a small effect. The concept of HEI resilience offers a theoretical framework for understanding inclusion as a dynamic and adaptable construct during a period of crisis. In contexts of change or crisis, resilient HEIs have shown the capacity to reconfigure structures and practices to maintain equitable access to resources, and support services for students (

Probst, 2022).

The findings of the study also reveal that social sustainability is a moderate predictor of the students’ satisfaction with academic life, which is in accordance with the existing literature (

Wolff & Ehrström, 2020;

Barnett-Itzhaki et al., 2025;

Ankareddy et al., 2025). Student satisfaction is multifaceted, encompassing academic quality but also experiences of social inclusion, campus climate, and the availability of supportive resources. When HEIs actively promote social sustainability, students are more likely to feel valued, engaged and connected to the campus community. These perceptions, in turn, may create a feedback loop (

H. Young & Jerome, 2020); students who feel their needs and voices are listened to are more likely to advocate for further HEI improvements. Over time, this reciprocal process not only enhances organizational culture and campus life but also equips students with the values and skills to promote social sustainability principles beyond the HEI context (

Hudler et al., 2019).

The findings of this study offer several practical implications for HEIs seeking to increase social sustainability initiatives, reflected in their turn, in the enhanced students’ academic satisfaction. By highlighting the medium and small predictive roles of social cohesion, inclusion, and HEI resilience, the results suggest targeted interventions that university policymakers can adopt to enhance student well-being.

Enhancing social cohesion may be considered a pivotal objective for HEIs. Social cohesion has been identified as the strongest predictor of students’ academic satisfaction, emphasizing the significance of cultivating trust, connectedness, and a sense of belonging within the academic community. To strengthen social cohesion, it is recommended that universities implement peer mentoring programs, collaborative learning environments, student learning hubs, and clubs, as well as community-building activities that foster mutual support among students (

M. R. Young et al., 2023).

The integration of inclusive initiatives into learning environments can be achieved through a systematic approach. The considerable impact of inclusion on student satisfaction emphasizes the need for HEIs to shift from a largely compliance-driven approach to diversity policies to a proactive implementation of inclusion strategies. This may involve redesigning curricula in a manner that reflects a diversity of perspectives, implementing assessment practices free from bias, and ensuring equitable access to resources for all students, including those from marginalized groups.

The concept of HEI resilience can be strengthened to not only overcome crises but also promote student confidence in institutional stability. The capacity of resilience of a

HEI can be supported by engaging students in the co-creation of an adaptive approach, thereby involving them as active partners in promoting institutional sustainability (

Duchek, 2020).

The findings of this study suggest that HEIs should adopt a holistic approach to social sustainability, given the multidimensional nature of student satisfaction. Nowadays, a limited focus on academic quality or employability outcomes is inadequate. Instead, HEI policymakers should recognize that relational and organizational factors, such as peer support, inclusivity, and resilience, also shape student satisfaction. The incorporation of these components into the sustainability initiatives of HEIs has been evidenced to enhance their long-term institutional reputation and competitiveness (

Probst, 2022).

Research has highlighted the significance of participatory governance, whereby students actively engage in decision-making processes, as primary contributors to the effectiveness of European universities (

Klemencic, 2014). In the case of Romania, where student participation in institutional governance is often characterized by formality rather than substance, social cohesion is frequently associated with informal networks and peer support structures (

Curaj et al., 2020). Moreover, in the Romanian system, inclusion has been formalized through affirmative action and the provision of student support services, yet, persistent inequalities exist—particularly between students residing in urban and rural areas (

Stăiculescu et al., 2022). The implementation of inclusive policies, in isolation, has been demonstrated to be inadequate in the absence of a concomitant institutional culture that offers support (

Varga et al., 2021). Furthermore, in Romania, efforts to build HEI resilience are still in their early stages of development, often limited to digital infrastructure or financial contingency planning. However, EU-funded capacity-building projects indicate an emerging recognition of HEI resilience as a component of sustainability (

Curaj et al., 2020).

The recommendations for HEIs to achieve social sustainability consist of the following practices:

For ensuring inclusion, HEIs should provide equitable access for all students, including marginalized or underrepresented groups, and elaborate and implement inclusive curricula and accessible teaching methods;

For ensuring Social Cohesion, HEIs should promote trust, collaboration, and a sense of belonging of students to the academic community, as well as encourage them to participate in mentorship programs and extracurricular activities;

For ensuring HEI Resilience, it should be developed flexible academic teaching and administrative structures and robust support systems, to adapt to disruptions, while promoting inclusion and social cohesion;

For ensuring long-term organizational social sustainability, HEIs should align the organizational sustainable goals to a broader social sustainability program of the EU or of a country. They should also ensure that the principles of equity, inclusion, and cohesion are integrated into their strategic planning and policies;

For ensuring student satisfaction based on social sustainability principles, HEIs should engage students and staff members in the decision-making processes, policy development, as well as in the co-creation of institutional solutions. Based on evidence-based approaches, it is also recommended to measure and continually improve programs and interventions dedicated to social sustainability by promoting mental health, emotional support, and the inclusion of students.

Limitations and Further Research Directions

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. The present study relied on cross-sectional data, which captures relationships at a single point in time, which raises issues of generalizability. It is recommended that future research employs longitudinal designs to examine how these constructs evolve and also to provide more substantial evidence of causality (

Podsakoff et al., 2012).

Moreover, the study was conducted within a single HEI, which may limit the generalizability of findings to other cultural, geographical, or institutional settings. A comparative study encompassing a range of countries and university types (public versus private, large versus small) could offer insights into how context influences the dynamics of social sustainability, HEI resilience, inclusion, social cohesion, and students’ academic satisfaction (

Altbach et al., 2019).

The data were collected using self-reported questionnaires, which have been demonstrated to be subject to biases such as social desirability bias or standard method variance (

Podsakoff et al., 2003). Although statistical examinations were conducted to mitigate these issues (e.g., Common Method Bias and VIF values), it is recommended that future studies employ a combination of self-reported data alongside objective or behavioral indicators (e.g., retention rates, academic performance, or institutional records) to enhance the validity of the research.

The convenience sampling method presents some limitations, as for instance selection bias and overrepresentation of certain groups of participants. It is recommended for further research to use larger sample sizes and mixed-methods approaches, which may offer the possibility of capturing several perspectives of the participants who are underrepresented in convenience samples.

The conceptual model demonstrated a moderate explained variance. While this finding is considered acceptable within the Social Sciences, it suggests that other relevant factors which influence students’ academic satisfaction should be included in the model; some of the factors are digital readiness, financial security, or academic self-efficacy (

Aman et al., 2023). It is recommended that future research employs mixed-methods approaches, integrating qualitative methods such as interviews or focus groups, to uncover students’ understanding of how they perceive HEI resilience, social cohesion, and inclusion, or social sustainability in their academic environments (

Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018).