The Interface Between Inclusion and Creativity: A Qualitative Scoping Systematic Review of Practices Developed in High School

Abstract

1. Introduction

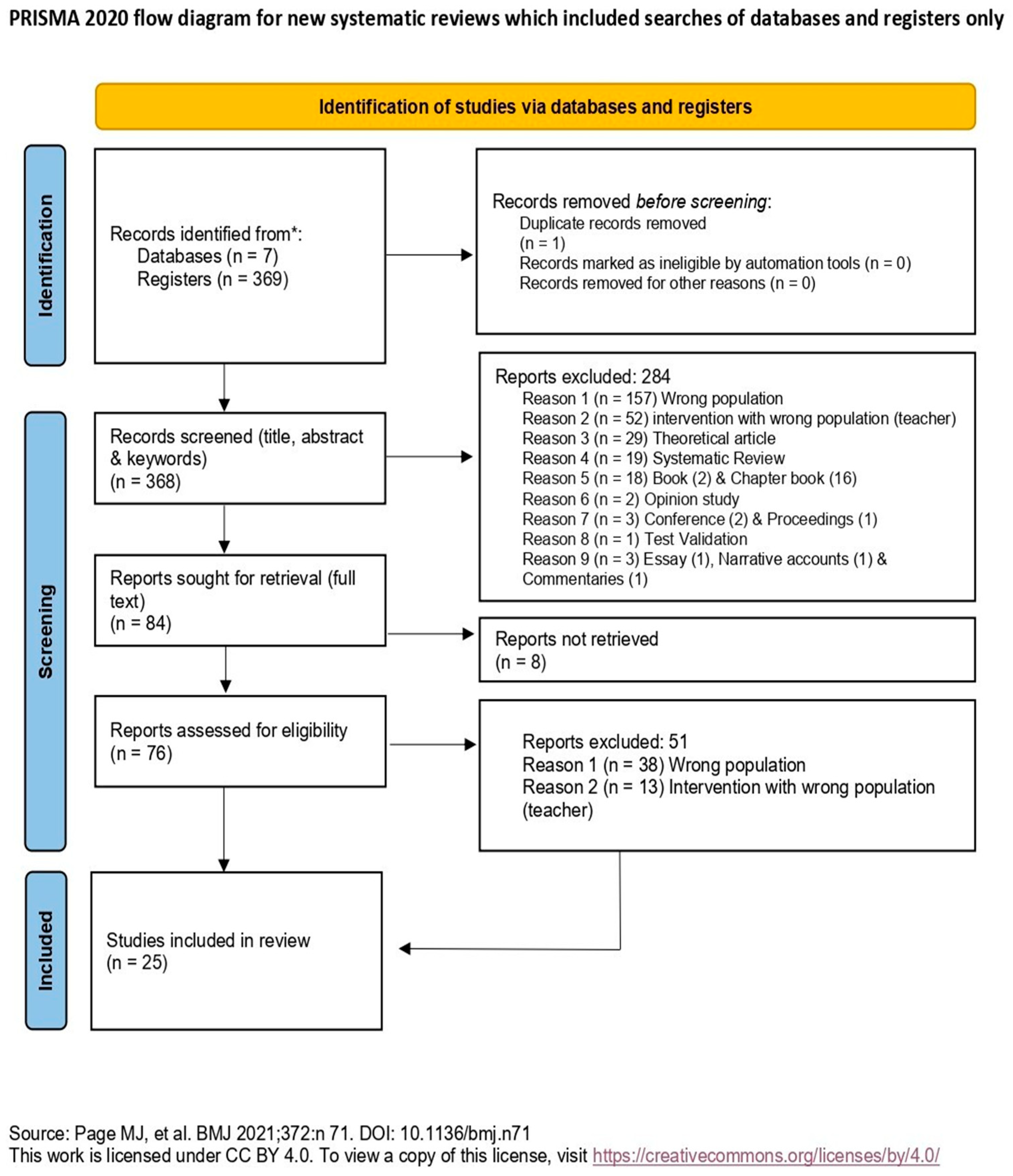

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection Criteria

2.2. Analysis

3. Results

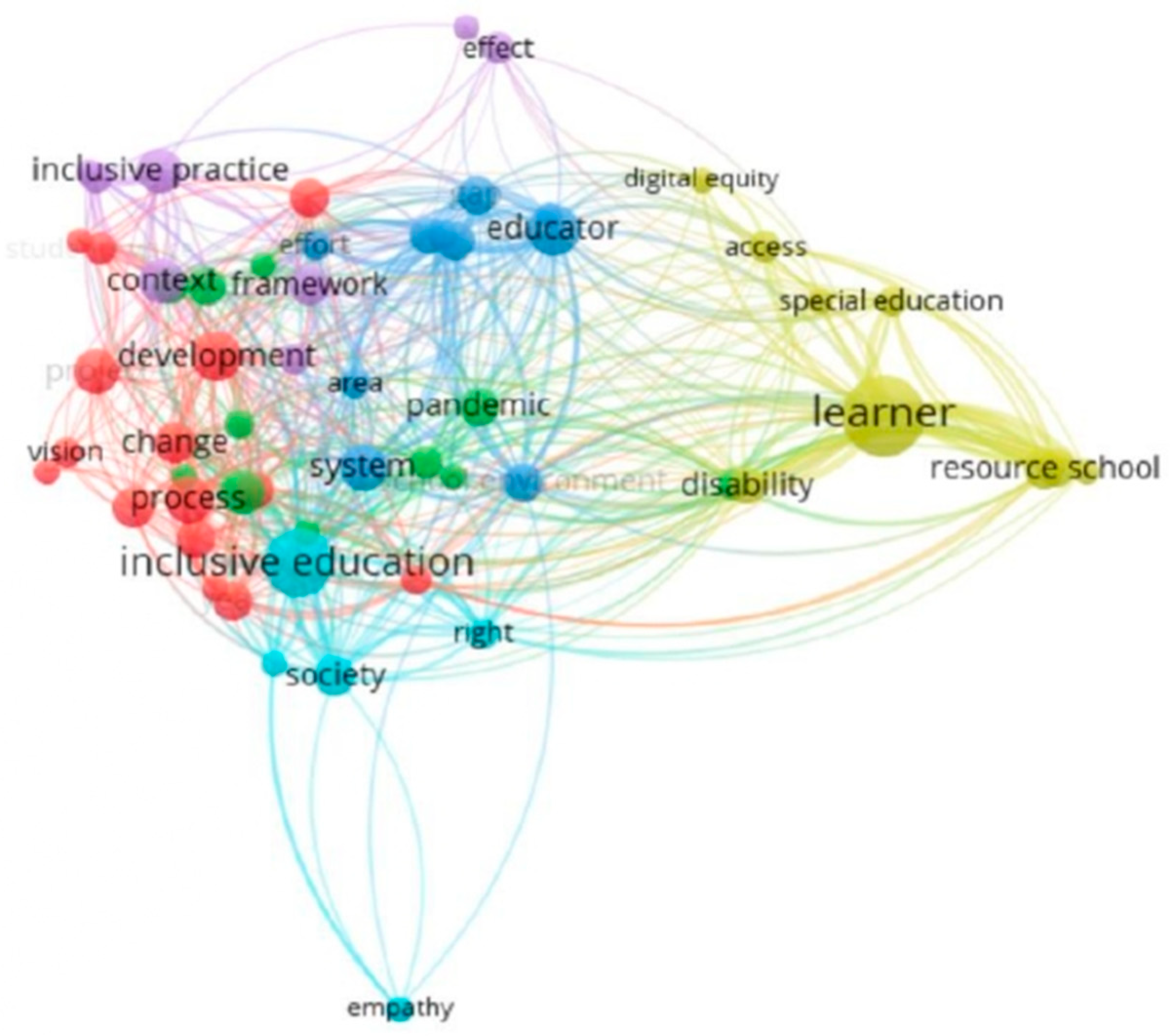

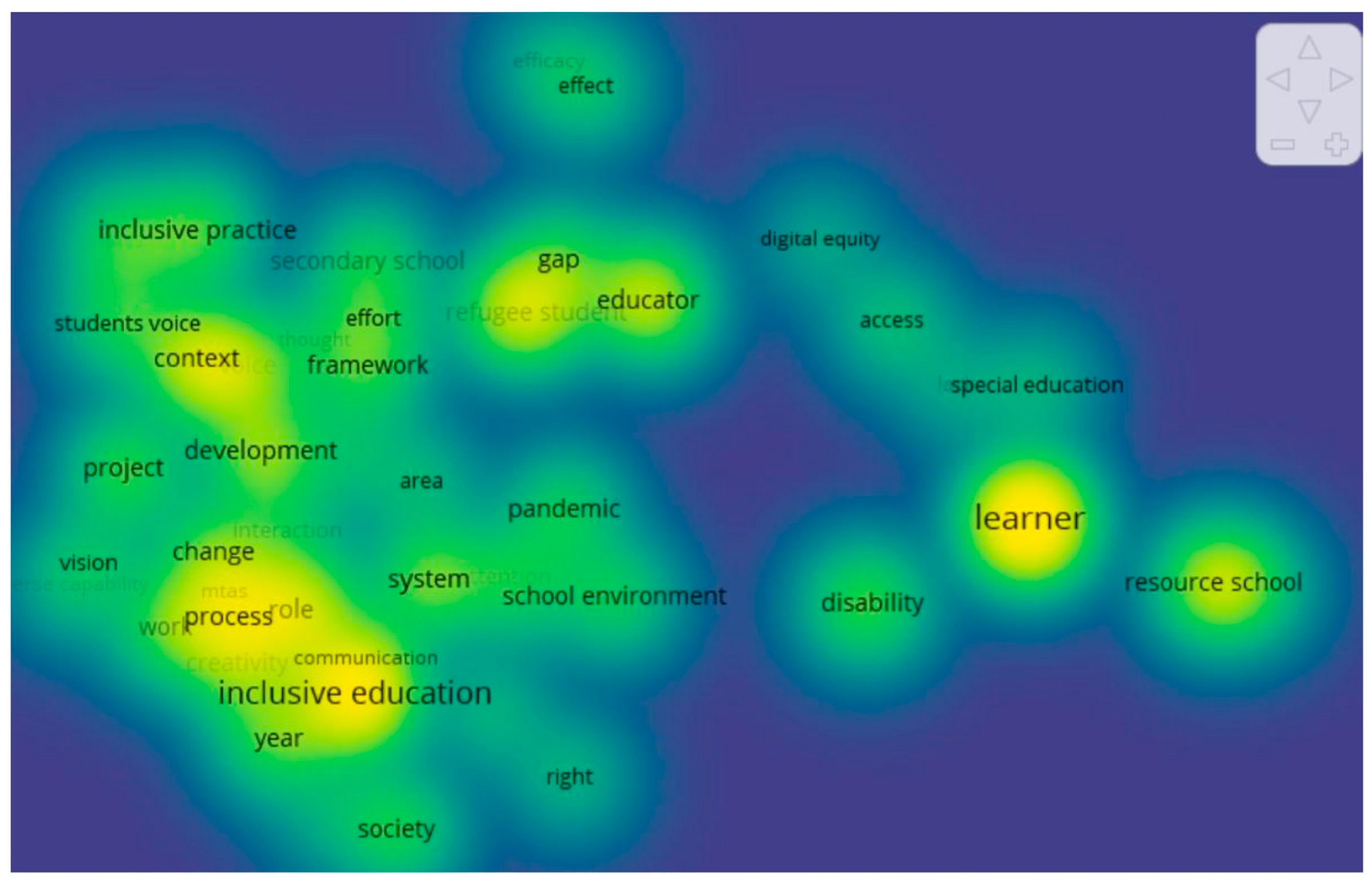

Bibliometric Mapping via Term Co-Occurrence (VOSviewer)

4. Discussion

4.1. Inclusive Strategies in High School

4.1.1. Inclusion in Multiple Spaces

4.1.2. Reorganization of Curriculum Proposals

4.2. Creative Strategies in High School

4.2.1. Creative Potential in Inclusive Contexts

4.2.2. The Relevant Role of Teachers in the Development of Inclusive and Creative Practices

4.3. Correlations Between Studies

4.4. Limitations

4.5. Recommendation for Future Research

4.6. Research Outlook and Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AER | Alternative Educational Robotics |

| CP | Cerebral Palsy |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| ICTs | Information and Communication Technologies |

| LSENs | Learners with Special Educational Needs |

| MTA | Multisensory Teaching Approach |

| PLC | Professional Learning Community |

| PCR | Culturally Responsive Teaching |

| PTL | Principal Transformational Leadership |

| PBL | Project-Based Learning |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RE | Robotic Education |

| SARS-Cov-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| STEAM | Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics |

| TITB | Teachers’ Inclusive Teaching Behavior |

| UDL | Universal Design for Learning |

References

- Alencar, E. M. L. S. (2007). Criatividade no contexto educacional: Três décadas de pesquisa [Creativity in the educational context: Three decades of research]. Revista Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 23, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ambili, J., Haihambo, C. K., & Hako, A. N. (2024). Challenges faced by learners with multiple disabilities at a resource school in the Oshana region of Namibia. British Journal of Special Education, 51(2), 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arana, J., Lapresa, D., Anguera, M. T., & Garzón, B. (2016). Procedimiento ad hoc para optimizar el acuerdo entre registros observacionales [Ad hoc procedure for optimising agreement between observational records]. Anales de Psicologia, 32(2), 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnau Gras, J., Anguera, M. T., & Homez Benito, J. (1990). Metodología de la investigación en ciencias del comportamiento [Methodology of behavioral sciences research]. Universidad de Murcia. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, A., Pennycook, C., & Barr, L. (2024). ‘It didn’t feel like something extra we had to do; It was something we all looked forward to’—How school-based professional learning communities can reimagine teacher professional learning for inclusive practice. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice. early online publication. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H., Evans, D., & Luu, B. (2023). Moving towards inclusive education: Secondary school teacher attitudes towards universal design for learning in Australia. Australasian Journal of Special and Inclusive Education, 47(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity. Harper Collins. [Google Scholar]

- Elkan, E. M., Stan, B. C., Papuc, A.-M., Ban, A. E., Goreftei, R. E. B., Bulai, D. L., Enache, M. M., & Ionascu, G. (2021). The difficult path to school—The schooling of pupils with special educational needs during the pandemic. Archiv Euromedica, 11(5), 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feito Alonso, R. (2013). El IES Miguel Catalán: La fuerza de la normalidad [IES Miguel Catalán: The power of normality]. Revista de Educación, 360, 338–362. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. (2005). Pedagogia da Autonomia: Saberes necessários à prática educativa [Pedagogy of autonomy: Essential knowledge for educational practice]. Paz e Terra. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. (2008). Pedagogia da esperança. Paz e Terra. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes, A. V. L. (2024). Student voices in creative teaching practices with digital media: A meta-ethnographic research. Ethnography and Education. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar]

- González-González, C., Violant-Holz, V., Infante Moro, A., García, L. C., & Guzmán, M. D. (2021). Robótica educativa en contextos inclusivos: El caso de las aulas hospitalarias [Educational robotics in inclusive contexts: The case of the hospital classrooms]. Educación XX1, 24(1), 375–403. [Google Scholar]

- Guilford, J. P. (1950). Criatividade [Creativity]. Psicólogo Americano, 5(9), 444–454. [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks, M., & Xeketwana, S. (2024). Translanguaging for learning in selected English First Additional Language secondary school classrooms. Reading & Writing, 15(1), a502. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Seda, C., & Pantić, N. (2025). Exercising teacher agency for inclusion in challenging times: A multiple case study in Chilean schools. Education Sciences, 15(3), 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B., & Mughal, R. (2024). Towards a critical pedagogy of trans-inclusive education in UK secondary schools. International Journal of Inclusive Education. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakos, M. (2022). A third space for inclusion: Multilingual teaching assistants reporting on the use of their marginal position, translation and translanguaging to construct inclusive environments. International Journal of Inclusive Education. advance online publication. [Google Scholar]

- Krumm, G., & Lemos, V. (2012). Artistic activities and creativity in Argentinian school-age children. International Journal of Psychological Research, 5(2), 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemeshchuk, M., Pisnyak, V., Berezan, V., Stokolos-Voronchuk, O., & Yurystovska, N. (2022). European practices of inclusive education (experience for Ukraine). Amazonia Investiga, 11(55), 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourens, H., Moodley, J., & Joosub, N. (2024). When we came back the ball was just not rolling: Special needs educators—Perspectives of improvisation through the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 24(3), 796–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mampaso Desbrow, J., López-Riobóo Moreno, E., & García Pérez, M. (2022). Creatividad como medida cognitiva en jóvenes con discapacidad intelectual [Creativity as a cognitive measure in young people with intellectual disabilities]. Revista de Estilos de Aprendizaje, 15(I), 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantoan, M. T. E. (2015). Inclusão escolar: O que é? Por quê? Como fazer? Summus. [Google Scholar]

- Mantoan, M. T. E., & Lanuti, J. E. O. E. (2021). Todos pela inclusão escolar: Dos fundamentos às práticas [Uniting for school inclusion: From foundations to practices]. Editora CRV. [Google Scholar]

- Messiou, K., & Hope, M. (2015). The danger of subverting students’ views in schools. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 19(6), 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, E. (2015). Ensinar a viver: Manifesto para mudar a educação. Sulina. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, E. (2018). A cabeça bem-cheia: Repensar a reforma, reformar o pensamento [The well-made head rethink the reform, Reform the thought]. Bertrand Brasil. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, C. (2021). Educating from difference: Perspectives on Black cultural art educators’ experiences with culturally responsive teaching. Canadian Journal of History/Annales Canadiennes D’histoire, 56(3), 353–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, J. A. (2019). Inovar para mudar a escola. Porto Editora. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 71, 372. [Google Scholar]

- Pittman, J., Severino, L., DeCarlo-Tecce, M. J., & Kiosoglous, C. (2021). An action research case study: Digital equity and educational inclusion during an emergent COVID-19 divide. Journal for Multicultural Education, 15(1), 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pletsch, M. D. (2020). O que há de especial na Educação Especial Brasileira? [What’s special in the brazilian special education?]. Momento Diálogos em Educação, 29(1), 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangkuti, N., Setyarini, S., Rodliyah, R. S., & Rakhmafithry, D. (2025). Harnessing community voices: Transformative audio narratives for inclusive English learning in rural Indonesia. Changing English. Early Online Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Rapanta, C., Garcia-Mila, M., Remesal, A., & Gonçalves, C. (2021). The challenge of inclusive dialogic teaching in public secondary school. Comunicar, 29(66), 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roemer, R. C., & Borchardt, R. (2015). Meaningful metrics: A 21st century librarian’s guide to bibliometrics, altmetrics, and research impact. American Library Association. [Google Scholar]

- Sacristán, J. G. (2008). El valor del Tempo en la Educación. Morata. [Google Scholar]

- Sassaki, R. K. (2009). Inclusão: Acessibilidade no lazer, trabalho e educação [Inclusion: Ensuring universal accessibility in leisure, work, and education]. Revista Nacional de Reabilitação (Reação), XII, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sassaki, R. K. (2023). As sete dimensões da acessibilidade. Larvatus Prodeo. [Google Scholar]

- Sedláčková, D., & Kantor, J. (2022). Lived experiences of learners with cerebral palsy educated in inclusive classrooms in the Czech Republic. Frontiers in Education, 6, 800244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A. A. F., Oliveira, G. S., & Ataídes, F. B. (2021). Pesquisa-ação: Princípios e fundamentos [Action research: Principles and foundations]. Prisma, 2(1), 2–15. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, E. K., & Dias, K. L. (2024). Accessible and sustainable technology in education: Experiences of educational alternative robotics. Brazilian Journal of Education, Technology and Society, 17(1), 195–212. [Google Scholar]

- Subban, P., Woodcock, S., Bradford, B., Romano, A., Sahli Lozano, C., Kullmann, H., Sharma, U., Loreman, T., & Avramidis, E. (2024). What does the village need to raise a child with additional needs? Thoughts on creating a framework to support collective inclusion. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 30(5), 668–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, S. (2001). Creatividad social. Valor educativo y bien social [Educational value and social well-being]. Revista Creatividad y Sociedad, 9, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Torre, S. (2005). Dialogando com a criatividade: Da identificação à criatividade paradoxal. Madras. [Google Scholar]

- Torre, S. (2006). Teoría interactiva y psicosocial de la creatividad [An interactive and psychosocial theory of creativity]. In S. Torre, & V. Violant (Coord.), Comprender y evaluar la creatividad (pp. 123–154). Aljibe. [Google Scholar]

- Torre, S. (2009). Escolas criativas: Escolas que aprendem, criam e inovam [Creative schools: The case of schools that learn, create, and innovate]. In M. Zwierewicz, & S. Torre (Coord.), Uma escola para o século XXI: Escolas criativas e resiliência na educação (pp. 55–69). Insular. [Google Scholar]

- Torre, S. (2023). Escolas criativas: Olhar o presente e o futuro com outra consciência [Creative schools: Viewing the present and the future with a new consciousness]. In M. Zwierewicz, & S. Torre (Eds.), Escolas criativas: Reflexões, estratégias e ações com projetos criativos ecoformadores (PCE) (pp. 9–20). Círculo Rojo. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Troncoso Recio, R., Cortés Redín, B., Romaní Fernández, L., & Serra Rodríguez, J. (2020). La creatividad como herramienta de inclusión en las aulas de Tecnología: Experiencia piloto a través de la música [Creativity as a tool for inclusion in technology classes: A pilot experience through music]. Revista Nacional e Internacional de Educación Inclusiva, 13(2), 238–264. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés, R. (2023). Prácticas de liderazgo en escuelas con orientación inclusiva y buenos resultados académicos [Leadership practices in schools with an inclusive orientation and strong academic results]. Educação & Sociedade, 44, e250906. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2023). VOSviewer (versão 1.6.20) [software]. Centre for Science and Technology Studies, University of Leiden. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Vásquez, L. G., & Velásquez-Medina, H. (2024). La empatía como herramienta para la educación inclusiva de alumnos con aptitudes sobresalientes de educación básica [Empathy as a tool for inclusive education of students with outstanding abilities in basic education]. Revista de Educación Inclusiva, 17(1), 338–356. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D., Huang, L., Huang, X., Deng, M., & Zhang, W. (2024). Enhancing inclusive teaching in China: Examining the effects of principal transformational leadership, teachers’ inclusive role identity, and efficacy. Behavioral Sciences, 14(3), 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, E., & Loeb, I. G. M. (2023). Absence unexcused: Using administrative data to explore patterns and predictors of habitual truancy in Pennsylvania. The High School Journal, 106(3), 166–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, M. (2024). Integration of displaced students into the culturally and linguistically different school environment. Review of Education, 12, e70004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N. | Author/s | Country | Purposes | Practices | Strategies | Evidence of Inclusion–Creativity Interface |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Ambili et al. (2024) | Zimbabwe | Investigates the challenges faced by students with multiple disabilities in a resource school originally designed for students with sensory (visual and auditory) disabilities. | Peer support; tutoring and mentoring. | Promoting the formation of fixed peer-tutoring pairs; providing individualized support sheets; using adapted resources (Braille machine); adapting materials. | The text analyzes the pedagogical practices used for students with multiple disabilities and the daily challenges to ensure inclusion. It does not relate to creativity. |

| 02 | Brennan et al. (2024) | Ireland | Analyzes Professional Learning Communities (PLCs), created and led within the school itself and supported by a partnership with the university. | Critical dialogue and shared practices; evidence of learning to boost traditional practice and plan inclusive lessons; diversified tasks on the same subject. | Exploring “Choice Boards”—boards with different activity options for students to choose how to approach a given content. | Creativity as a necessary construction to adapt, innovate, and develop teaching approaches that guarantee the inclusion of everyone. |

| 03 | Chen et al. (2023) | Australia | Investigates the attitudes of Australian secondary school teachers and how they relate to universal design for learning (UDL). | Using alternative ways to work on concepts (video, audio, and images); reviewing prior knowledge in each class; exploring different skills and their applications in different contexts; demonstrating learning in diverse ways (handwriting, keyboard, etc.); using support tools (grammar checker and calculator); individual definitions of learning goals. | Encouraging the use of videos, audio recordings, texts, and images; making maps, videos, and visual schedules. | Ability to build learning environments that respond to student diversity through flexible, innovative, and shared pedagogical proposals. |

| 04 | Elkan et al. (2021) | Romania | Analyzes how the COVID-19 pandemic affected the schooling of children and teenagers with special educational needs (SENs). | Flexible hybrid teaching; open digital resources; interdisciplinary team. | Promoting the recording of classes with subtitles; using platforms with digital accessibility; providing materials in multiple formats. | The focus of the text is on the adaptation of education for students with special educational needs (SENs) during the COVID-19 pandemic, without explicitly presenting any intention to promote creative processes. |

| 05 | Feito Alonso (2013) | Ecuador | Examines how the Institute de Educación Secundaria (IES) Miguel Catalán (Madrid) transformed school coexistence through democratic practices and, from there, began to adopt a set of pedagogical innovations. | Reorganization of teams (four–five students); one out-of-college volunteer: literary texts are read and commented on collectively in a “Platonic” style; intensive use of “cyberstudent”; extended library hours; cultural projects (theater, museums, and cinema); afternoon monitoring to compensate for low family cultural capital. | Developing posters, murals, visual panels, texts, videos, and music; exploring artistic materials. | Creative and inclusive practices improved the coexistence problem in the institution through interactive groups and dialogic readings. |

| 06 | Fuentes (2024) | Spain | Conducts a meta-ethnography of fourteen ethnographic studies to produce knowledge about how creative teaching practices mediated by digital media can promote inclusive education based on students’ voices, interests, and experiences. | Using digital games to introduce Aboriginal culture to mathematics (Australia); radio art workshops with young immigrants (USA); audiovisual narratives about everyday life in the neighborhood (Spain); a “Free” camera in the room to record important moments (Spain); a blended model (USA) giving autonomy to weekly goals; heterogeneous groups with cell phones for cooperative learning (Brazil); “Cluster Spaces” of digital games in early childhood education (Scotland); “Digital storytelling” workshops on stereotypes with students (Italy). | Applying digital games such as Guitar Hero; creating audiovisual projects; conducting radio and podcast workshops; producing digital stories. | Valuing the voices, experiences, and interests of students, especially those with vulnerable backgrounds. |

| 07 | Hendricks and Xeketwana (2024) | South Africa | Use of translanguage (isiXhosa ↔ English) to improve English learning, confidence, and student engagement. | Translanguage in exploratory and presentational speech; bilingual wall materials; guided translation of academic vocabulary. | Encouraging participation in bilingual reading; using activities with visual glossaries; implementing collaborative translation tasks; creating presentations in both one’s mother tongue and additional languages; reading and writing practices through oral discussions, songs, or collective reading. | The text addresses creativity from the moment at which diversity ceases to be understood as a limitation and begins to be understood as a driving force of the educational process. |

| 08 | Herrera-Seda and Pantić (2025) | Chile | Comprehends how Chilean teachers exercised their professional agency during the COVID-19 crisis. | Adaptation of classes for distance learning; universal support for learning and well-being; collective work among teachers. | Creating collaborative emergency lesson planning among teachers; establishing peer support groups; adapting activities focused on well-being; proposing small-group video calls; validating tasks with flexible deadlines. | The text discusses the teaching capacity to respond critically to problematic situations and seek solutions and the mobilization of varied resources during a pandemic. |

| 09 | Johnson and Mughal (2024) | United Kingdom | Comprehends how experiences in British secondary schools can guide a critical pedagogy focused on trans inclusion. | Safety environment and symbols: use of badges/pronouns, rainbow lanyards, permission for non-binary uniforms, gender-neutral restrooms; dialogical curriculum; reconceptualization of students as partners; transaffirmative teaching stance; development of transaffirmative school policies and continued training of faculty. | Selecting texts and authors who are trans or queer; using inclusive visual materials; paying attention to inclusive language (neutral language). | Creativity and inclusion complement each other, allowing for the recognition of personalized responses to multiple ways of being. |

| 10 | Kakos (2022) | United Kingdom | Understanding how multilingual teaching assistants use their marginal position, translation, and translanguaging to create third spaces. | Translanguaging: the practice of utilizing a speaker’s entire linguistic repertoire without strictly adhering to the boundaries of “named” languages. | Producing posters, images, illustrated cards, pictographic symbols, physical objects, visual charts, educational software, and interactive videos. | Third-space pedagogical spaces: places where marginalized students come together to creatively overcome their problems and increase their linguistic repertoires; creative pedagogy. |

| 11 | Lemeshchuk et al. (2022) | Ukraine | Analyzes the implementation of European inclusive education practices in Ukraine. | Individual portfolios; alternation of activities every 10–20 min; work in heterogeneous groups; teacher’s assistant; play-based learning and games; individualized task planning. | Encouraging the rotation of short, varied activities; using educational games, role play, and artistic activities; employing visual and auditory resources; adopting assistive technologies. | The application of creativity through tasks and methods to facilitate the learning and inclusion of every student, including those with special needs; creative tasks. |

| 12 | Lourens et al. (2024) | South Africa | Investigates how teachers in South African special schools improvised, with flexibility and creativity, to maintain the teaching of learners with special educational needs (LSENs) during the various phases of the COVID-19 lockdown. | 1. Without Internet or devices: creation of personalized notebooks and cards; delivery and collection by the school driver; 2. classes with connectivity; promotion of healthy habits; intensive reteaching of lost content and strengthening of emotional bonds. | Exploring assistive technologies; using accessible digital platforms; providing materials that respect different learning modalities. | Creativity acts as a tool to translate the principles of inclusion into real practices, especially in emergency situations. |

| 13 | Mampaso Desbrow et al. (2022) | United Kingdom | Evaluates the creativity of young people with intellectual disabilities as an indicator of cognitive performance. | Outlines general foundations and guidelines for inclusive and creative practices but does not exemplify concrete methods or activities. | Integrating art materials; using accessible digital technologies; employing multimodal resources; implementing hybrid learning environments. | The incorporation of the development of creative thinking into pedagogical practices as an essential skill for young people with intellectual disabilities. |

| 14 | Messiou and Hope (2015) | England | Analyzes what tensions arise when trying to use student voices to improve inclusive practices. | Students choose and arrange nine cards about learning, stimulating debate and revealing priorities; focus groups are moderated by university researchers; teachers plan, observe, and review lessons based on student feedback. | Organizing student assemblies; using collaborative murals; conducting interviews, written records, and group discussions; employing bulletin boards, recordings, and reflective reports. | The transformation of students’ voices into inclusive and creative pedagogical practices. |

| 15 | Murray (2021) | Canada | Investigates how Black cultural arts educators perceive and practice culturally responsive teaching (PCR) in Ontario schools. | Community and dialogue: converting the classroom into a horizontal and decolonized space for coexistence. Dance, percussion, and oral and visual arts activities that require cooperation, critical reflection, and leadership from students. | Encouraging video and poetry presentations; using art materials; promoting reflective journals; employing accessible digital technologies. | The use of cultural arts as a pedagogical tool or approach to promote inclusive education. |

| 16 | Pittman et al. (2021) | United States of America | Investigates faculty perceptions and practices regarding multicultural and educational issues related to the fast increase in online environments during coronavirus (COVID-19) experiences. | Diagnosis and continued dialogue. Curriculum flexibility and formative assessment; inclusive teaching and universal design for learning (UDL); partnerships and co-teaching; infrastructure and digital equity. | Using multimodal materials; adopting adaptive technological resources; implementing diversified assessment tools; employing visual aids and manipulatives. | The study examines the interaction of several elements, such as multiple disabilities, poverty and family stress, and the consequences for students. There is no evidence of creative processes. |

| 17 | Rapanta et al. (2021) | International scope Portugal Coordination | Verifies whether inclusive dialogic practices can be successfully implemented in secondary education in Portuguese and Spanish public schools and examines teachers’ participation in a short development program. | Dialogical curriculum; discussion techniques: deepening ideas, active listening. | Selecting collaborative digital platforms; using digital authoring software; implementing Virtual Learning Environments (VLEs); developing digital portfolios. | Creativity appears indirectly in the text, breaking with traditional and exclusionary pedagogical practices, offering teachers and students diverse ways of teaching, learning, and interacting. |

| 18 | Rangkuti et al. (2025) | Indonesia | Investigates how community-produced audio narratives can transform English teaching for visually disabled students in rural Indonesia. | Community-produced audio narratives; culturally relevant curriculum; multisensory learning; dialogical and collaborative methodology; teacher training with action research; intergenerational engagement. | Using visual maps and charts; keeping written and graphical records; incorporating local and culturally situated resources. | The text demonstrates that educators can creatively transform limitations into opportunities, such as community-driven audio narratives. |

| 19 | Sedláčková & Kantor (2022) | Czech Republic | Comprehends how young people with cerebral palsy (CP) experience schooling in mainstream classes in the Czech Republic. | Individual support classes; curriculum adaptation (mathematics and physics); extension of test time; verbal assessment; copy of materials prepared by the teacher; presence of a teaching assistant. | Proposing the use of art materials; employing multimedia and digital resources; developing learning portfolios; creating adapted learning environments. | The study explores the experiences lived by students with cerebral palsy (CP) in inclusive education environments, not highlighting creative elements in pedagogical practices. |

| 20 | Souza and Dias (2024) | Brazil | Expands the possibilities of applying RE (Robotic Education) by integrating creative and active methodologies, presenting Alternative Educational Robotics (AER). | Pedagogical proposal of Alternative Educational Robotics (AER), aiming to democratize access to technology using recyclable materials and electronic scrap. | Providing electronic scraps; using recyclable materials; adopting open-source software; employing accessibility tools. | The way in which the lack of resources was overcome, with the use of recyclable materials, is a demonstration of creativity. |

| 21 | Subban et al. (2024) | Australia | Identifies elements that help schools adopt a “village mindset”—that is, a collective responsibility—for the inclusion of students with additional needs. | Welcoming community school culture of belonging and shared values; everyone works together; intentional dialogue between teachers, families, colleagues, and students; cooperative planning; ambitious goals and flexible methods that combine skills from multiple professionals. | Using varied teaching resources; adopting assistive technologies. | Creativity is crucial for inclusion and should be used as an intentional pedagogical resource. |

| 22 | Troncoso Recio et al. (2020) | Spain | Discusses the implementation of a cooperative musical creativity project. | Project-Based Learning (PBL) and cooperative work; integration of technology, arts, and ICT (Information and Communication Technologies); reflective rituals and dialogue; inclusive adjustments in process and assessment. | Exploring the creation of murals and posters; preparing field diaries. | Through music, students with different abilities actively participated in the project, strengthening the group’s integration. |

| 23 | Vázquez-Vásquez and Velásquez-Medina (2024) | Mexico | Analyzes the relevance of empathy in teaching practice as a tool for the inclusion of students with outstanding attitudes (high abilities) in Mexican basic education. | Awareness-raising programs/teacher training; empathy activities in the classroom; task enrichment, controlled acceleration, and talent grouping; focus on socio-affective factors. | Encouraging the production of informational texts and cultural narratives; using posters, murals, and visual resources; providing bilingual materials. | Creativity and empathy are central elements to the promotion of an inclusive education environment that is responsive to singularities. |

| 24 | Wang et al. (2024) | China | Investigates the effects of the transformational leadership of principals on the inclusive behavior of teachers. | Principal Transformational Leadership (PTL); inclusive teaching behaviors (TITBs): content, process, and product. | Applying robotics kit resources; using recyclable and reusable materials; employing educational software; using multimedia equipment; incorporating artistic materials. | Creativity is related to teachers who, through diverse teaching approaches and innovative strategies, can meet the needs of students in diverse classrooms. |

| 25 | Yilmaz (2024) | Uganda Türkiye | Investigates how Turkish schools are dealing with the challenges of integrating Syrian refugee students. | Games, music, videos, and cartoons to teach vocabulary and curriculum content; pairwise system; intercultural projects and activities; teacher training. | Promoting playful and multimodal teaching using games, music, videos, and cartoons; organizing mixed cultural activities, such as songs from the students’ own cultures and typical foods. | The adaptive and innovative solutions that educators have implemented to address the difficulties of refugee students are elements related to creativity in the educational context. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zluhan, M.R.; Corrêa, S.d.S.; Zwierewicz, M.; Violant-Holz, V. The Interface Between Inclusion and Creativity: A Qualitative Scoping Systematic Review of Practices Developed in High School. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1281. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101281

Zluhan MR, Corrêa SdS, Zwierewicz M, Violant-Holz V. The Interface Between Inclusion and Creativity: A Qualitative Scoping Systematic Review of Practices Developed in High School. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1281. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101281

Chicago/Turabian StyleZluhan, Mara Regina, Shirlei de Souza Corrêa, Marlene Zwierewicz, and Verónica Violant-Holz. 2025. "The Interface Between Inclusion and Creativity: A Qualitative Scoping Systematic Review of Practices Developed in High School" Education Sciences 15, no. 10: 1281. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101281

APA StyleZluhan, M. R., Corrêa, S. d. S., Zwierewicz, M., & Violant-Holz, V. (2025). The Interface Between Inclusion and Creativity: A Qualitative Scoping Systematic Review of Practices Developed in High School. Education Sciences, 15(10), 1281. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101281