1. Introduction

Teachers’ perceptions regarding artificial intelligence in the educational field (AIEd) is a topic of growing interest and has been extensively addressed in several studies. These investigations provide a comprehensive understanding of teachers’ beliefs and attitudes towards AIEd, underlining the importance of considering various factors influencing its acceptance and use in different educational settings.

In general, it should be noted that the integration of information and communications technology (ICT) in the educational process has constituted a relevant axis of analysis within didactic research [

1], evolving towards studies focused on specific aspects such as the influence of the TPACK model on the incorporation of ICT in teaching [

2], the perception of the effectiveness of video in language teaching [

3], the decision to integrate or not ICT in educational practice [

4,

5], how perceptions of technological competencies affect their integration [

6], the potential of ICT to support the learning of students with dyslexia [

7], its effectiveness and applicability at initial educational levels [

5], and its viability in various disciplines [

8].

To summarize the importance of teachers’ beliefs about the application of ICT, the conclusions of Tondeur, van Braak, Ertmer, and Ottenbreit-Leftwich [

9], derived from a meta-analysis on this topic, indicate (1) the existence of a reciprocal relationship between pedagogical beliefs and the concrete use of ICT; (2) the identification of certain beliefs as perceived obstacles; (3) the correlation between specific beliefs and specific types of ICT use; (4) the significant role of beliefs in teachers’ professional development; and (5) the relevance of the school context in shaping beliefs about ICT.

The notable advance of AI, especially after the introduction of ChatGPT3 in the educational field, has encouraged research on attitudes, levels of acceptance, available training, and the impact of beliefs about teaching on students’ use or rejection of AI in educational practice. It is crucial to highlight the importance of teachers being trained in the use of AI, both in teaching and in research [

10,

11,

12,

13].

These beliefs are influenced by factors such as the age of the teachers. A study by Yuk and Lee [

14] explored the perceptions, experiences, knowledge, concerns, and intentions to use Generative AI (GenAI) among Generation Z (Gen Z) students and teachers from Generation Y (Gen Y) in higher education.

The findings of various investigations highlight the importance of teachers’ beliefs in teaching artificial intelligence (AI).

According to Adekunle, Temitayo, Adelana, Aruleba, and Sunday [

15], teachers’ confidence in their ability to teach AI significantly predicts their intention to integrate AI into their teaching practice, underscoring their perception of its usefulness and educational relevance. This phenomenon is not homogeneous but varies depending on the discipline taught and the academic level at which teachers practice their profession [

16].

Uygun [

17] conducted a literature review to examine teachers’ beliefs about using AI in education. They identified key factors influencing teachers’ acceptance of this technology, highlighting the need to understand their perspectives for effective adoption in educational settings.

Various empirical studies have shown that teachers’ acceptance of AI is influenced by various factors. For example, Ma and Lei [

18] conducted a study in China that analyzed the factors influencing teachers’ acceptance of AI. Similarly, Bacci and Caviezel [

19] also investigated how teachers perceive and accept AI in the educational context, using ClarityTutor as a case study.

Additionally, several studies have integrated theoretical technology acceptance models to better understand faculty attitudes toward AI. Al Darayseh [

20] applied the Technology Acceptance Model to examine teachers’ acceptance of AI-based educational systems. Likewise, An et al. [

21] proposed an integrative model that considers various factors that affect the acceptance of AI in teaching.

Other studies have applied psychological theories to examine teachers’ acceptance of AI in specific educational contexts. Chocarro et al. [

22] integrated the Technology Acceptance Model and Social Cognitive Theory to examine the acceptance of AI in primary education. Furthermore, teachers’ acceptance of AI may vary depending on the educational context and specific technology characteristics, as demonstrated by the studies of Ayanwale et al. [

23] and Crompton and Burke [

24] at different educational levels.

In this context, the interaction of multiple factors influences the intention to continue using AI in education. Zulkarnain et al. [

25] investigated the factors influencing teachers’ continuing intention to use AI education systems, integrating the Expectation Confirmation Model and the Task Technology Adjustment Model.

Furthermore, it has been shown that teachers’ beliefs about the conceptions of learning significantly influence how and how often they use information and communications technology (ICT) in teaching. Research has been carried out addressing both the general use of ICT [

4,

26,

27,

28] and specific technologies such as mixed reality [

29], the Moodle platform [

28], or the digital whiteboard [

30]. These investigations highlight the complexity of the factors that affect technology integration in educational environments, showing that teachers’ pedagogical beliefs play a crucial role in adopting and effectively using technological innovations in education.

In the psychoeducational field, two predominant paradigms are recognized regarding conceptions of learning and teaching: behaviorism and constructivism. While behaviorism suggests that knowledge is transmitted directly to the student, constructivism proposes that the learner actively constructs knowledge through personal experience and social interaction [

28]. In this context, Choi, Jang, and Kim [

31], identified that teachers with a constructivist orientation are more likely to incorporate AI in education than those with a more traditional or transmissive approach.

In some way related to the theme of beliefs, we find the work carried out on the “degree of acceptance of technologies” by teachers. Furthermore, in this regard, the models used to analyze the degree of acceptance of a technology by its potential users have been different. The first of them was the TAM model (“Technology Acceptance Model”) formulated by Davis [

32], which postulates that the intention to use technology is influenced by two main dimensions, perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use, which influence the attitudes one has about ICT, which will determine their intentions to use and its use. The model has been used for the analysis of different technologies, such as virtual training [

33], augmented reality [

34], or immersive reality [

35].

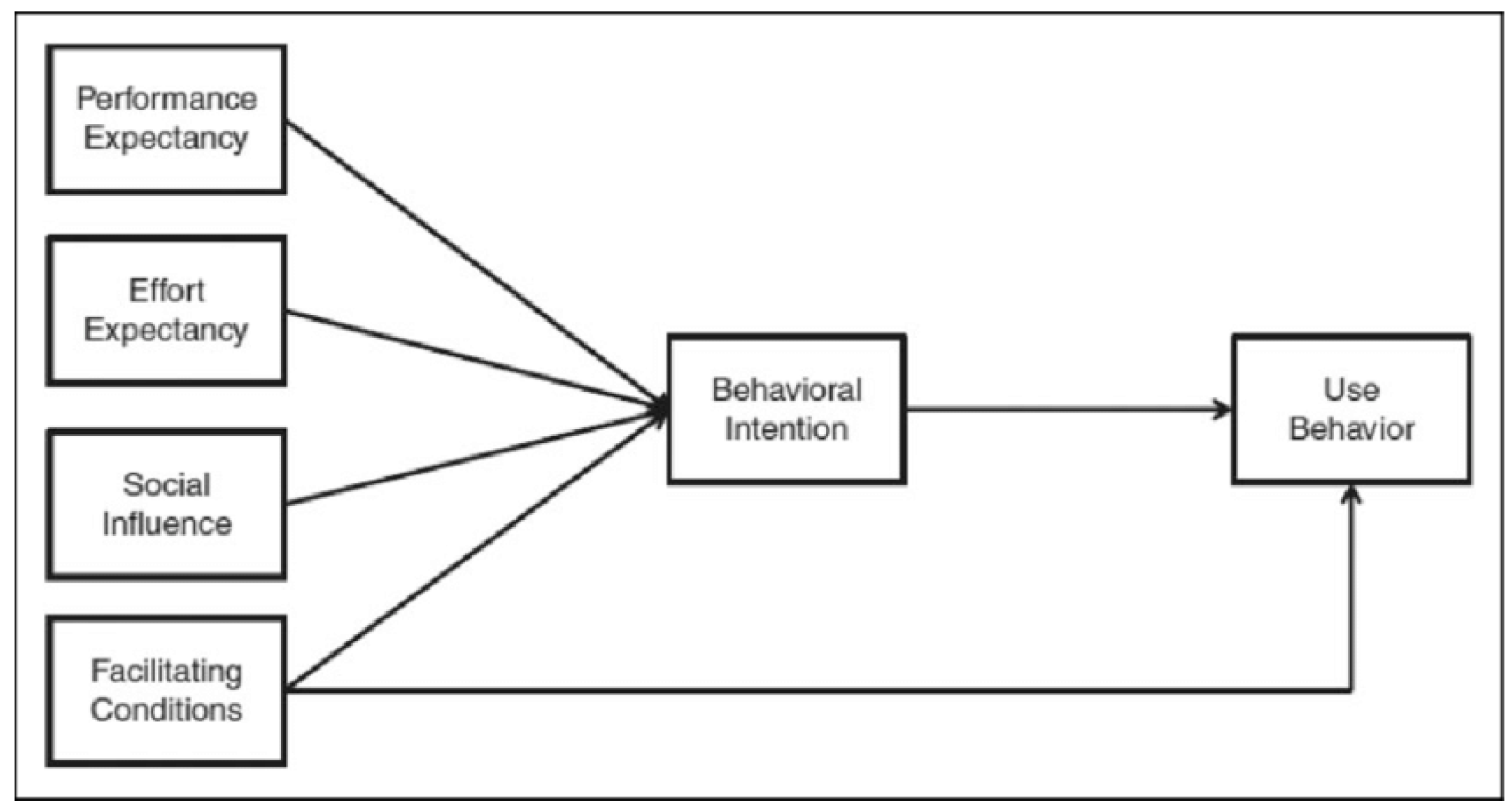

Against this model, Venkatesh et al. [

36], unifying different proposed acceptance models, including TAM, formulated their “Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology” (UTAUT). This model seeks to explain the acceptance and use of technology, which depends on four large dimensions: performance expectations, effort expectations, social influence, and facilitating conditions. The model that was reformulated by Venkatesh, Thong, and Xu [

37] with the so-called UTAUT2 incorporates three new dimensions: hedonic motivation or pleasure achieved in its use, the value of the price, and the degree to which a person automatically uses that technology. This model, as different authors have suggested [

38,

39] in the bibliographic studies they have carried out, is increasingly used by researchers compared to previous proposals.

It should be noted that in our study, we have only considered the first of the new variables incorporated in the UTAUT2 since, for the objectives that were sought to be achieved, the relevance of the variables price and automatic use of technology was not considered, leaving the model configured as presented in

Figure 1.

According to various studies [

40,

41], “performance expectations” are understood as the level at which an individual considers that the use of artificial intelligence in education (AIEd) contributes to improving their performance in the activities they carry out. “Effort expectations” refer to the degree to which it is believed that the AIEd will not require excessive effort to use. “Social influence” implies the degree of influence the close environment (family, friends, and colleagues) exerts on the individual to adopt AIEd. “Facilitating conditions” encompass the level and volume of available resources and support that make adopting and using AIEd easier. “Hedonic motivation” relates to the pleasure or enjoyment of using AIEd. “Intention to use” is defined as an individual’s purpose in using the AIEd in their educational practice. At the same time, “usage behavior” indicates the extent to which the person uses the AIEd in their professional teaching activity.

It should be noted that both the UTAUT and UTAUT2 models have been used to examine the degree of acceptance of various technologies. Research based on the UTAUT has explored the acceptance of the metaverse [

41], mobile devices [

42], and virtual reality [

43]. On the other hand, UTAUT2 has been applied in the analysis of technologies such as augmented reality [

44], the metaverse [

45], virtual training platforms [

46], and the use of artificial intelligence [

40], including its educational application [

47].

Our study aims to understand whether teachers want to use artificial intelligence in education (AIEd), whether they use it, and what factors influence these decisions, such as their friends’ opinions, previous experience, perceived usefulness and ease of use, and pedagogical beliefs.

3. Results and Discussion

Initially, the means and standard deviations in the different dimensions that made up the instrument will be presented (

Table 5).

In all cases, the mean scores exceeded the threshold of 3.5, indicating a significantly high level of acceptance of AIEd by teachers. This finding suggests a marked predisposition towards its implementation, as evidenced by the high average score in the “intention to use” dimension with a mean value of 5.75. However, it should not be forgotten that the high value reached in the standard deviations demonstrates a high dispersion of the data.

Table 6 shows the average scores obtained in the dimensions related to the analysis of the teachers’ constructivist and transmissive pedagogical beliefs.

As can be seen, there is predominantly a tendency among teachers to adopt constructivist positions for the development of training actions, with an average score of 6.49, in contrast to transmissive positions, which obtained an average score of 3.63. However, it is also essential to highlight the high score achieved in the standard deviation found in the transmissive option, which implies a notable dispersion in the answers provided by the teachers.

The scores obtained for analyzing the proposed hypotheses are detailed below. We used non-parametric statistical tests such as Mann–Whitney U and Kruskal–Wallis H. Additionally, an average rank analysis was carried out in cases where these tests indicated the presence of significant differences between the groups [

52]. Before this analysis, it was verified that the sample distribution did not follow a normal distribution. This verification was carried out through a kurtosis study and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (

p = 0.000). An exhaustive review of the data distribution was carried out to ensure the validity of the results. In addition to the methods mentioned above, a visual analysis of the histograms and an examination of possible outliers were carried out. These additional measures were taken to ensure the statistical findings’ robustness. This additional verification process strengthens confidence in interpreting the results obtained in the statistical analysis.

It should be noted that in all cases, the following hypotheses were formulated:

Null hypothesis (H0): There are no significant differences between the variable “x” and “y”, with an alpha risk of being wrong of 0.05.

Alternative hypothesis (H1): There are significant differences between the variable “x” and “y”, with an alpha risk of being wrong of 0.05.

- (a)

There are significant differences, at the 0.05 significance level, depending on the teachers’ gender in the dimensions of the UTAUT2 referred to the AIEd.

In this case, the Mann–Whitney U statistic was applied to analyze the significant differences, achieving the results shown in

Table 7.

The results did not allow us to reject H0 at a significance level of p ≤ 0.05. Consequently, it can be noted that there were no significant differences in the different dimensions identified in the formulated UTAUT2 model.

- (b)

There are significant differences, at the 0.05 level of significance, depending on the gender of the teachers in terms of their constructivist pedagogical beliefs and transmissive pedagogical beliefs.

To analyze whether there were significant differences in teachers based on gender regarding the constructivist or transmissive beliefs they had regarding teaching, the Man-Whitney U was applied again, achieving the results presented in

Table 8.

The results obtained allowed us to reject the H0, which refers to the non-existence of significant differences. Consequently, it can be said that teachers’ transmissive and constructivist pedagogical beliefs differed depending on their gender.

Since H0 was rejected in both cases and H1 was accepted, with a risk of

p ≤ 0.05 of being wrong, and to know in favor of which gender the most significant differences occurred, the range test was applied, achieving the results offered in

Table 9.

The values achieved in the range test allowed us to point out that female teachers have a greater tendency to have constructivist pedagogical beliefs. On the contrary, male teachers present a tendency towards transmissive pedagogical beliefs.

- (c)

There are significant differences, at the 0.05 level of significance, depending on the teachers’ age in the dimensions of the UTAUT2 referred to as the AIEd.

To determine if there were significant differences at the significance level of

p ≤ 0.05 concerning the different dimensions of the UTAUT2 depending on the age of the teachers, the Mann–Whitney test was applied, obtaining the values presented in

Table 10.

The results achieved did not allow us to reject H0 at the level of p ≤ 0.05 in the dimensions of “performance expectations”, “social influence”, “facilitating conditions”, “usage behavior”, and “intention to use”. Consequently, it can be noted that the age of the teachers did not influence the evaluations made regarding the citation dimensions.

On the contrary, the scores achieved allowed us to reject H0 and accept H1 with a risk

p ≤ 0.05 of being wrong in the case of the dimensions “expectations of effort” and “hedonic motivation”. Next, to determine which age levels of the teachers where the differences occurred, we applied the range test again, reaching the values presented in

Table 11.

The values achieved with the range test indicate that the youngest teachers (“less than 25 years old” and “25 to 30 years old”) obtained the highest scores in both dimensions. Scores decrease as the age of the teachers advances.

- (d)

There are significant differences, at the 0.05 level of significance, depending on the teachers’ age in constructivist pedagogical beliefs and transmissive pedagogical beliefs.

To determine whether there were significant differences depending on the teachers’ age, we considered whether the teachers’ age impacted their beliefs. We applied the Kruskal–Wallis statistic, obtaining the values in

Table 12.

The data obtained did not allow us to reject any H0 at a significance level of p ≤ 0.05. Consequently, it can be indicated that the age of the teachers did not influence the pedagogical, transmissive, or constructivist beliefs they had about teaching.

- (e)

There are significant differences, at the 0.05 level of significance, depending on the modality the teacher teaches (face-to-face, distance learning, or both) in the dimensions of the UTAUT2, referred to the AIEd.

To analyze whether there were significant differences at the level of significance at the level of

p ≤ 0.05 in the different dimensions of the UTAUT2 depending on the modality in which the teachers taught, the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied again, reaching the values that are presented in

Table 13.

The values found did not allow us to reject H0 at the significance level of p ≤ 0.05 in the following dimensions of the UTAUT2: “facilitating conditions”, “hedonic motivation”, and “usage behavior”. On the contrary, they did allow us to reject it at the level of significance indicated in the dimensions “performance expectations”, “effort expectations”, “social influence”, and “intention to use”.

Again, the range test was applied to determine where such differences were established in the accepted H1, reaching the values shown in

Table 14.

The values indicate that the teachers who, in some way, solely or in combination with face-to-face, work in the distance modality have higher perceptions in the four dimensions mentioned in the UTAUT2.

- (f)

At the 0.05 significance level, there are significant differences depending on the modality in which the teacher teaches: constructivist pedagogical beliefs and transmissive pedagogical beliefs.

We again applied the Kruskal–Wallis test to determine whether the teachers differed depending on the teaching modality and their pedagogical beliefs (

Table 15).

As can be seen from the two analyzed statistics, only H0 was rejected, at the significance level of ap ≤ 0.05, concerning transmissive pedagogical beliefs. Presented in

Table 16 is the rank test for this accepted hypothesis.

Once again, the teachers who worked remotely offered the highest average range but at a very short distance from those who worked exclusively in person.

- (g)

There are significant differences, at the 0.05 level of significance, depending on the area of knowledge where the teachers work in the dimensions of the UTAUT2 referred to as the AIEd.

Finally, we analyzed whether there were differences depending on the area of knowledge the teachers taught. In this case, the score achieved is presented in

Table 17.

The values allowed us to reject H0 at ≤0.05 for all dimensions, except for “intention to use”.

Table 18 shows the values achieved in the cases of acceptance of H1 to determine the area of knowledge that stood out.

The analysis of the range test allowed us to offer a series of conclusions; on the one hand, the teachers who worked in the knowledge area of “Social and Legal Sciences” obtained the highest scores in all the dimensions analyzed. Teachers from different areas occupied the second positions; thus, in “performance expectations”, the second position was occupied by those in Sciences, in “expectations of effort” by those in Engineering and Architecture, in “social influence” by those in Arts and Humanities, in “facilitating conditions” by those in Arts and Humanities, in “hedonic motivation” by those in Sciences, and finally in “usage behavior” by those in Sciences.

- (h)

There are significant differences, at the 0.05 level of significance, depending on the area of knowledge where teachers work: constructivist pedagogical beliefs and transmissive pedagogical beliefs.

The Kruskal–Wallis test was applied to analyze this hypothesis, achieving the results presented in

Table 19.

As shown in

Table 19, H0 was rejected with an alpha risk of being wrong of

p ≤ 0.01 in the hypothesis referring to transmissive pedagogical beliefs. Furthermore, the results achieved after applying the range test to determine which area of knowledge such differences occurred in are presented in

Table 20.

- (i)

There are differences between teachers’ pedagogical beliefs and “usage behavior” regarding AIEd.

In this case, we applied the Spearman Rho statistical test to evaluate the relationship between the intentionality of use, the traditional teaching style, and the constructivist teaching style. The Spearman test does not depend on the normal distribution of the data. Furthermore, this test allows capturing any non-linear associations between these variables, which is crucial given the complexity of the interactions between the intentionality of use and traditional and constructivist teaching styles.

The test obtained the values presented in

Table 21.

The data obtained allowed us to point out two aspects: (a) that the correlations established between both types of beliefs and the teacher’s “usage behavior” towards AIEd are positive and significant, and (b) that there is a greater tendency of teachers who can be considered constructivists, according to the instrument used, to use the AIEd than those considered transmissive.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The conclusions derived from our research address various aspects, the first of which is the evaluation of the instrument’s reliability. It was found that this instrument exhibits considerably high levels of reliability, which allows the analysis of not only the dimensions identified from the UTAUT2 model but also those used to explore constructivist and transmissive pedagogical perspectives. It is essential to highlight that, in this last case, the values obtained coincide with the findings of Choi, Jang, and Kim in their 2023 study.

This finding underlines the robustness and consistency of the measurement instrument used in our research, which confers validity to the study’s results. The instrument’s high reliability provides a solid basis for interpreting the data collected and, therefore, for the conclusions drawn from them.

The average scores achieved in the dimensions that make up the UTAUT2 model and that indicate the level of acceptance of this technology by teachers are pretty high, and in the case of “usage behavior”, which would determine the degree to which the teacher uses AIEd in their professional activity, notably exceed the central value of the distribution offered. It is essential to highlight that “intention to use” is the most significant and influential dimension concerning “usage behavior”. Therefore, the intention of use fundamentally determines and directs its use by the teacher.

The average values achieved in the part of the instrument aimed at knowing whether the teachers tended to have a constructivist or transmissive belief in teaching indicate a solid constructivist orientation, which exceeds by almost double the score achieved by teachers with a tendency to a transmissive belief. This would imply that methodological changes are being promoted in teaching, where innovation and active methodologies are gaining traction [

25].

The research has indicated that the teacher’s gender is not a determining variable for the teacher’s acceptance and use of AIEd, specifically in both the “usage behavior” and their “intention to use”, which are the dimensions that would finally explain the degree of acceptance of AIEd by teachers. The results achieved are like those obtained by Alenezi, Mohamed, and Shaaban [

10].

Although differences were found regarding gender and the tendency towards a transmissive or constructivist pedagogical belief, where female teachers tended to place themselves in a constructivist orientation, this differentiation was not found when the age of the teachers was considered.

The research has shown that the age of the teachers was not generally shown to be significant in the “usage behavior” and “intention to use” of the IAEA. Nevertheless, differences were obtained in “expectations of effort” and “hedonic motivation”, where younger teachers achieved higher scores. These teachers consider that using AIEd will not require much effort and that its use will give them some enjoyment and pleasure.

Significant differences were found concerning the modality in which the teachers taught, and the teachers who taught in some way in the distance modality were those who presented a greater tendency in the dimensions “performance expectations”, “expectations of effort”, “social influence”, and “intention to use”. Then, it could be said that these teachers consider AIEd very useful for their professional activity, that its use will not require a great effort, and that they have a solid intention to use it.

It was found that there are apparent differences in teachers’ acceptance of AIEd depending on the areas of knowledge the teacher taught in. Teachers in “Social and Legal Sciences” show greater acceptance and intention to use AIEd. At the same time, they tend to have transmissive pedagogical beliefs.

Our study’s findings suggest that teachers with constructivist beliefs are more likely to integrate artificial intelligence in education (AIEd) into their teaching practice than those with transmissive orientations. This result is consistent with previous research conducted by Choi, Jang, and Kim [

31], who also found a positive relationship between constructivist beliefs and teachers’ willingness to adopt educational technologies. However, in their study, they used the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) as a theoretical framework, not UTAUT2, which was used in this work.

It is important to note that, despite the consistency in the results, the specific context of AIEd integration in teaching may differ between the theoretical models used to analyze technology acceptance. In this sense, the constructivist approach can emphasize the importance of active learning, collaboration, and student construction of knowledge, which could influence teachers’ willingness to adopt technologies that promote these principles.

Furthermore, regarding the expectation of effort, we observed that teachers with transmissive beliefs assigned higher scores, indicating a perception of greater difficulty in using AIEd. This result suggests that these teachers may perceive additional obstacles or greater complexity in implementing AIEd compared to their counterparts who hold constructivist beliefs. This difference can be attributed to different conceptions of the role of the teacher and the student in the teaching–learning process, as well as expectations of how AIEd can support or challenge these traditional roles.

The results of this study have implications of both practical and theoretical relevance regarding the knowledge of AIEd. Our review’s contribution is that it is one of the first empirical works that addresses teachers’ perceptions regarding AIEd through the UTAUT2 model. Other studies have been developed using the technology acceptance model (TAM) [

31] or the UTAUT2 model, but with university students [

47].

This study presents several limitations that should be considered in future research related to AIEd Integration. First, the level of respondents’ exposure to the use of AIEd was not assessed. The lack of this information may limit the understanding of how prior experience with technology influences teachers’ attitudes and practices.

Finally, it would be beneficial to include qualitative data in future research to explore further the determinants influencing teachers’ acceptance of AIEd. Qualitative methods like focus group interviews or nominal groups allow researchers to identify the underlying mechanisms in teachers’ attitudes and perceptions toward AIEd. This combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches could provide a more holistic and detailed understanding of the phenomenon studied.