Abstract

This paper explores how concept maps can be structured based on researcher narration as a systems thinking (ST) approach in science education to portray the systemic nature of developmental work by chemists on solutions related to sustainability. Sustainability cannot be achieved without a systemic approach that considers all the domains of prosperity and well-being—ecological, social, and economic. Science education must respond to this challenge accordingly and find effective ways to include the ST approach. Data were collected from three semi-structured, in-depth interviews with chemists. The analysis was carried out using qualitative content analysis and modelling the systemic structures in concept maps as articulated by the chemists. The results show that authentic narratives of chemists’ developmental work can be used as material in a concept mapping exercise to reveal several ST elements and learning objectives, including leverage points and delays, that have not been presented in previous exercises. The chemists’ descriptions were also found to address the challenge of sustainability education by depicting a holistic and multidimensional picture of the reality where the developmental work is conducted. Furthermore, all three domains of sustainability were identified. The economic and industrial perspectives were especially valuable from the science education viewpoint.

1. Introduction

We live in an enormously complex world. Natural sciences, empirical and exact by nature, have tackled this complexity by isolating objects of study from their broader contexts. This method is known as the reductionist approach [1], which has also been a central approach in chemistry. During this era of the reductionist approach, knowledge and technology in chemistry have propelled forward and led to new materials and chemicals, improving human life drastically. At the same time, modern human activity is increasingly threatening ecosystems, and as a result, human life and livelihoods as well. The boundaries of safe operation space have been transgressed at least in the areas of biochemical flows, freshwater change, land system change, biosphere integrity, climate change, and novel entities [2].

There is no question that these ill-defined complex dilemmas must be solved urgently. This requires input from all fields of science and experts, not least chemists [3]. In response, sustainability competencies have been developed as a framework to cultivate the capability to address and resolve such sustainability-related challenges. Competencies are a combination of knowledge, skills, and attitudes, aiming to establish substantive learning objectives within educational contexts, and they are particularly to be used in a collaborative and interdisciplinary manner [4]. Central to these competencies is systems thinking (ST), an approach that focuses on the interconnectedness and complexity of systems, thereby enabling holistic problem-solving [4,5,6]. ST can be seen as an opposite approach to the reductionist approach, yet it should not replace it but rather be adopted alongside it [7,8].

Sustainability issues are inherently complex, often cutting across domains such as the environment, society, economics, and scales from local to global [9]. The UN has defined 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in its Agenda 2030, with the intent to tackle all aspects of sustainability, from ending hunger, protecting the natural environment, to securing global peace [10]. Moreover, the issues are frequently characterised by their wicked problems, controversial nature, and the need for ethical consideration. Wicked problems are complex, and messy, without the right solution [11].

Chemistry has a pivotal role in understanding, innovating, and applying solutions to environmental challenges, and ST must be part of the approach in chemistry [3,12,13,14]. Besides chemistry professionals, ST should be integrated into chemistry and other science education, especially in the sustainability context. This has been widely recognised by the chemistry education research community, and as such by the Journal of Chemical Education, which published a special issue entitled Reimagining Chemistry Education: Systems Thinking, and Green and Sustainable Chemistry [15].

In the context of chemistry education, diverse frameworks offer a variety of lenses through which sustainability can be viewed and integrated into educational practices. In general education, these include education for sustainable development (ESD) [16], environmental and sustainability education (ESE) [17], and eco-reflexive education [18]. Despite their differences, a common thread among these approaches is the holistic and interdisciplinary understanding of sustainability, which entails many aspects of sustainability and the importance of critical thinking and growing to be a responsible, aware citizen capable of evaluating sustainability targets, efforts, and policies. A step to achieving these learning goals is to provide pupils with a realistic understanding of chemistry’s role in sustainable development, including the complexity of the problems but especially the solutions.

The claim for strong and holistic sustainability expertise also comes from the industrial sector. Finnveden and Schneider [19] explored the sustainability skills sought by two major industrial companies from higher education graduates. They identified a crucial need for understanding complex sustainability issues that are intertwined with supply chains, stakeholder interests, and varying time horizons. The study highlighted the importance of grasping the interplay between technology and sustainability and the ability to communicate complex, multifaceted sustainability issues effectively, requiring sustainability literacy. It also emphasised understanding the impact of sustainability on business, including identifying opportunities and risks, and the ability to implement strategic sustainability actions practically.

According to Blatti et al. [20], ST is a great tool when a complex and holistic approach is required. It can increase the relevance and engagement of education when it is incorporated with authentic, real-world cases entailed by the range of sustainability, environmental, social, and economic domains [20]. The economic domain is especially found to be the least discussed aspect of sustainability education in chemistry, even though it is often the determinant [21,22]. Along with the economic domain, the industrial aspect should also be included in truly relevant chemistry education. Moreover, it is an essential part of how chemistry is connected to the environmental, social, and economic domains of sustainability issues [22].

Besides sustainability education, ST can be used to understand the science itself or nature of science (NOS), as it can be used to depict chemistry as a system, and it can be used to reveal the connections to the wider society [23]. This is also the ST context of this paper. We studied chemists who are developing sustainability-related solutions as part of the bigger systems that are connected to industry and the wider society, which can give a valuable outlook on how scientific research is interconnected with the wider society.

By now, there has been a good number of research projects and discussion about implementing ST in science education at all its levels. However, there is still need for the identification of suitable areas and interconnections of chemistry education fitting for the ST approach [24] and a lack of research on how to implement ST in chemistry teachers’ education [25].

ST has numerous definitions, yet it is commonly regarded as a collection of tools and a language for understanding, modelling, and communicating the structure, features, and functioning of complex systems [7,26]. At a higher level, this knowledge and understanding can be used to inject significant changes within the system or to refine one’s actions to align with it better. A principal objective of ST research within the field of chemistry education is to determine the relevant learning outcomes of ST for the curriculum. These outcomes encompass the tools and language—or practices and concepts—that are fundamental to ST. In this paper, we have referred to them as elements of systems thinking.

This study presents three descriptive cases, based on interviews with chemists. Through these cases, we highlight the systemic nature of chemists’ work and research conducted in the context of sustainability. The aim is to produce an understanding of research and development work through ST and to explore how it relates to larger sustainability-related systems, such as the circular economy and the bioeconomy. The data analysis is synthesised using a non-hierarchical concept map model to represent the systems arising from the chemists’ authentic work descriptions. The use of concept mapping and its adaptations is widespread in ST education [27,28,29]. Accordingly, the second aim of this study was to examine the extent to which the concept map approach, when applied to the authentic descriptions by chemists, can represent the central elements of systems thinking identified in the chemists’ accounts of developmental work on sustainability solutions.

This paper contributes to the field of science education through chemistry education research. Systems thinking (ST) is highly relevant in every STEM subject but manifests itself slightly differently in each discipline. In fields such as biology and earth sciences, ST has been studied for much longer compared to disciplines like chemistry, physics, and mathematics [25]. As an exploratory study, this approach has the potential to extend to other sustainability-related research work in other science fields. Since ST is inherently a holistic approach and sustainability issues are multidisciplinary problems, this approach has considerable potential to be integrated into STEM education.

This study explores how concept maps can be structured based on authentic narratives as the learning material for an application of ST in sustainable science chemistry education. By using chemists’ authentic narratives as the material, this research is a first step in creating a teaching module for ST in science education, that includes researchers as quest speakers or, ideally, even interviewees of the students. The former literature indicates numerous perks for quest speaker approaches [30]. They can introduce relevant topics outside the syllabus and present more relevant and current topics, and they can showcase a reality of the experts’ work and work environment. Writers mention that the outline and purpose of the quest speakers’ presentation should be outlined to meet desired learning outcomes.

Vesterinen and Aksela [31] have studied research group visits including interviews of researchers as part of NOS education for pre-chemistry teachers. Visits to research groups expose students to the interdisciplinary and collaborative nature of chemical research and the societal applications of scientific discoveries, making the learning experience more relevant and engaging. Writers point out that working in a laboratory does not always ensure deep understanding of NOS, but by active classroom discussion, students have the opportunity to reflect and process encounters, observations, and their interpretations, which can enhance their critical thinking skills and understanding of NOS.

By highlighting how individual researchers’ work relates to broader sustainability domains and larger systems, the study underscores the significance of their contributions to sustainable development. Crucially, it offers a more authentic perspective of the realities facing industrial production and economic prerequisites. This methodological exploration aims to identify effective strategies to integrate ST into chemistry education, by providing realistic examples that reflect the true complexity of sustainability challenges in the developmental work of scientists. Derived from this background, we have formulated the following research questions (RQ) to guide the research:

- Which broad sustainability-related systems is chemical research embedded in?

- What elements of systems thinking can be presented on the non-hierarchical concept map model?

Both RQs will be answered through chemists’ descriptions of the systemic nature of their work, related to developmental work on sustainability solutions. To understand the results comprehensively, we have prepared an extensive theoretical framework. The theoretical section starts with a broader perspective to sustainability and sustainable chemistry. After the wider view, we define ST and review earlier research of ST in education.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Sustainable Development and Sustainability

Sustainable development aims to build a way of life for humankind that does not compromise the natural world, while sustaining the basic needs for a good life for all. The World Commission on Environment and Development, in its 1987 report “Our Common Future” [32], offered a widely recognised definition of sustainable development: “Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (p. 41). This goal encompasses the pursuit of ecological, economic, and social sustainability.

These diverse aspects focus on the holistic development of human life to ensure the potential for a good life for all. The United Nations’ latest framework for global sustainability, introduced in 2015, comprises the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and 169 targets, aiming to cover all aspects of sustainable societies [10]. The framework is intending to unite the whole world to act to reach peace and prosperity for humans and the planet. The UN claims that SDGs

“…recognize that ending poverty and other deprivations must go hand-in-hand with strategies that improve health and education, reduce inequality, and spur economic growth—all while tackling climate change and working to preserve our oceans and forests.”[33]

Sustainable chemistry endeavours to achieve the same end as sustainable development in the field of chemistry, as science, and industry. Given that chemistry forms the molecular foundation of our society, sustainable chemistry must be comprehended not solely in terms of environmental safety but also as a means for achieving the SDGs of the United Nations [13]. This requires a ST approach that integrates multiple interconnected systems [3,12,13,14]. Anastas and Zimmerman [13] elucidate the need for a systemic approach in the chemistry sector in terms of SDGs, as they include the vast industrial chemistry sector. They show the extensive influence that chemistry has over societies, economies, and the environment, which are interlinked, and cannot be treated as separate sectors. The authors stress the need for sustainable chemistry to be inclusive, diverse, and responsive to various global contexts, advocating for an ecosystem approach involving economics, policy, interdisciplinary engagement, and regulation. A systems thinking approach is crucial for the productive utilisation of new chemistries that respect cultural, societal, ecological, and ethnic sensitivities, ensuring sustainable solutions in diverse regions and societies [13].

The SDGs have been criticised for having internal contradictions [34,35]. The writers claim that the goals of ecological integrity in particular cannot be fulfilled with the goal of economic growth. Le Blanc [36] argues for systemic management and an examination of the SDGs and their targets, advocating for an understanding of the interconnectedness of the goals. He further points out that a having sufficient understanding of the synergies and trade-offs within this system and the strategies, policies, and implementation could support sustainability advancements in a holistic manner. Despite decades of awareness regarding the likelihood of exceeding the planet’s ecological thresholds, humanity continues to breach these planetary boundaries [2]. Richardson [2], likewise, underlined the importance of a holistic approach in addressing the Earth system, vital for sustaining human life and all life forms on the planet.

In this paper, we seek to understand how the work of chemists engaged in developing sustainability solutions is connected to broad sustainability-related systems. A sustainability-related system is defined as a system that meets three criteria: 1. it comprises parts; 2. the parts are interconnected; and 3. the system has a purpose [7]. It relates to sustainability if it advances or supports a sustainable way of life, as defined by the WCED report [32]. Five sustainability-related systems were detected from the data. They are the bioeconomy, the circular economy, green transition, national security of supply, and the emergence of a new industrial sector or production. Next, these systems are briefly defined and explained.

2.2. Sustainability-Related Systems

As an effort to change the materials we consume, the bioeconomy is very much an enterprise of chemistry. Gawel et al. [37] describe the bioeconomy as an endeavour to transition from an economy primarily reliant on fossil raw materials to one focused on renewable biomaterials. This shift entails utilising biobased materials as raw materials for producing fuels, chemicals, and materials such as plastics. These biomaterials can originate from agriculture, forestry, marine sources, or from the side streams and waste streams of various industries.

The circular economy may be an even more ambitious effort to change the material economic system to reach sustainability. It is an attempt to change the current linear economy into a closed loop of materials. In a linear economy, a product is made from virgin materials, and after use, it is considered to be waste, to be dumped as landfill or burnt. In a pure circular system, there would be no waste. Instead, all the used materials could be turned into new materials for new products. The primary objective of circular economy is to minimise environmental harm by reimagining the product life cycle to require minimal input and production of waste [38].

The third current concept used for the change to a more sustainable way of life is green transition. It is used mainly in policy and official documentation aimed at describing the economic shift to prefer more sustainable technologies such as low-carbon solutions and the circular economy [39]. It promotes sustainable economic growth and constrains the overconsumption of natural resources. The objectives of the green transition are at the core of the EU’s new growth strategy, the European Green Deal, which aims for carbon neutrality by 2050, economic growth, and equality, ensuring “no person or no place is left behind” [40].

National security of supply refers to the strategy to safeguard essential societal functions in the event of serious incidents or emergencies, coordinated by The Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment [41]. It encompasses infrastructure, defence mechanisms, supply chain transitions from global markets to national production, and a competitive economy, all of which are crucial for the livelihood of the population, the national economy, and defence. National security of supply is considered to be a social sustainability-related system.

The emergence of a new industrial sector or production system is considered to be a sustainability-related system in this paper, as it fundamentally supports a well-functioning economy. It is the production mechanisms in modern societies that provide necessary goods and facilitate value-creating markets. New industrial production can also promote social and economic well-being, by generating employment and fostering industrial innovation. Furthermore, these examples derived from the data specifically aim to enhance environmental sustainability through the advancement of the bioeconomy or circular economy.

2.3. Systems Thinking

ST is a methodology that focuses not on individual parts but on how the components of a whole interact, creating a dynamic entity greater than the sum of its parts. It is a holistic approach that strives to understand the behaviour of the larger systemic constructions our world consists of, both natural and artificial, material and intangible. By understanding these systems and how they work, eventually, the ability can be gained to change and manipulate those systems effectively [7].

There is no universally accepted definition of ST, and its multifaceted nature has led to a diversity of definitions. York and Orgill [42], emphasising the definitions of ST in an educational context, highlight this diversity. They note that ST has been variously described (1) as an approach for examining and addressing complex behaviours from a holistic perspective; (2) as a method and outcome for understanding complex phenomena; (3) as an analytic technique for comprehending the behaviour of complex phenomena over time; and (4) as a skillset encompassing cognitive, metacognitive, and higher-order thinking abilities. Furthermore, ST is recognised for its dual role as both an instructional and a problem-solving tool, offering a unique language and set of tools for visualising and communicating complex systems. Monat and Gannon [26] give a pervasive and apt characterisation to ST in their literature review: it provides a perspective, language, and tools for understanding complex systems.

ST originates in Bertalanffy’s General System Theory and system science [26]. Yet, ST is not synonymous with the aforesaid approaches, as systems theory and systems science are ways to study systems as a phenomenon, while ST is a way of thinking. Or, as Cabreras et al. [43] argue, ST is conceptual; they point out that changing the way we think is changing how we conceptualise. Thus, learning ST is changing the way we build our mental models.

ST should be a part of general knowledge, since it has the potential to provide a better understanding of reality. Holistic understanding is especially needed with sustainability issues, as they demand an understanding of a wide range of factors and the interplay between various sectors, including the environment, the economy, and societal factors [4,5,6]. Perhaps most importantly, ST is a way of understanding problems and their root causes in all of their complexity [4,7,43]. Sustainability issues cannot be solved as one small problem at a time but by considering the whole, the complex system they assemble. Ideally, the ST approach should lead to pursuing nexus solutions that address more than one problem at once [44].

There are several ST models and lists of the skills of systems thinking in the ST literature, with a quite divergent focus, as excellently elucidated by Semiz [45]. One of the more used models in the educational context is from Assaraf and Orion [27], who propose a three-level compilation of eight skills:

Level I: analysis of system components

- 1.

- Identify the components of a system and processes within the system.

Level II: synthesis of system components

- 2.

- Identify relationships among the system’s components.

- 3.

- Identify dynamic relationships within the system.

- 4.

- Organise the systems’ components and processes within a framework of relationships.

- 5.

- Understand the cyclic nature of systems.

Level III: implementation skills

- 6.

- Make generalisations.

- 7.

- Understand hidden dimensions of the system.

- 8.

- Think temporally: retrospections and prediction.

This framework was used to introduce ST to the chemistry education community by Orgill, York, and MacKellar [8]. A year later, York and Orgill [42] generated a tool called ChEMIST Table, for planning ST approaches for chemistry education. Based on the comprehensive ST literature, they refined the five most adequate ST learning objectives for chemistry education, which are the following:

- Recognise a system as a whole, not just as a collection of parts.

- Examine interconnections and relationships between the parts of a system and how those interconnections lead to cyclic system behaviours.

- Identify variables that cause system behaviours, including unique system-level emergent behaviours.

- Examine how system behaviours change over time.

- Identify interactions between a system and its environment, including the human components of the environment.

York and Orgill [42] propose that their list of relevant objectives can guide the understanding of how holistic and systems-oriented the exercise of the teaching approach is. Not every ST exercise needs to cover them all, but some of the elements should be included in a holistic manner to reach ST teaching goals. Moreover, they have used phrasing, which elucidates what students should do in the exercise, since ST learning is best attained by active participation. Further, they argue that ST is both a holistic and an analytic procedure, and therefore, the exercises can be focused on more analytic or holistic approaches.

2.4. Elements of Systems Thinking

Both frameworks capture many relevant aspects of ST, but they lack a couple of central ST aspects. Those are stocks and flows, leverage points, and delays [7,26]. Based on the two frameworks above and the three additions mentioned here, the basic elements of ST are next briefly defined:

- Interconnectedness and complexity: These are foundational attributes of any system. A systems thinker should possess the ability to recognise the components of a system and identify their interconnections, as well as possess the capacity to navigate the complexity that emerges from this web of interactions.

- Cyclic nature: Systems often exhibit feedback loops, typically modelled using causal loop diagrams. These diagrams elucidate the cyclic interplay within the system, in which an effect circulates through the structure, returning to its starting point, as either reinforcing or balancing feedback. For instance, climate change demonstrates both types of feedback: the thawing of permafrost may release methane, exacerbating global warming (a reinforcing loop), whereas increased water vapour could lead to more cloud formation, potentially cooling the planet by reflecting solar radiation (a balancing loop).

- Stocks and flows: These represent accumulations (stocks) and transfers (flows) of materials, information, or other resources within a system. Stocks, such as a population, change slowly over time, while flows, like birth or death rates, can increase or decrease these accumulations. These dynamics are often visualised through stock and flow diagrams.

- Emergence: This is the phenomenon whereby a system exhibits properties and behaviours not evident from its components alone, underscoring the principle that systems are more than the sum of their parts. The iceberg model is a common tool for illustrating emergence.

- Temporal thinking: This involves contemplating the potential evolution of a system. While precise predictions may require graphs or simulations, it is crucial to acknowledge the likelihood of change and consider various future trajectories.

- Leverage points: These are points within a system where small interventions can lead to significant impacts. Identifying these points can be relatively easy in an intuitive sense, yet, as Donella Meadows noted, intuition often leads to counterproductive actions.

- Delay: This is a fundamental aspect of systems that is intuitively understandable. Delays represent the time lags within system processes and can significantly influence system behaviour.

- Hierarchy and boundaries: These entail the ability to delineate a system from its environment and to conceptualise it as being composed of subsystems. As an example, this concept helps in understanding how a cell can be seen as a system containing organelles (subsystems) and, simultaneously, as part of larger systems such as tissues and organisms. Defining system boundaries is crucial, even though these boundaries can sometimes be ambiguous.

Modelling systems is at the heart of ST practices. There are multiple ways to model systems, such as the Systemigram [46], the recently found SOCME (System Oriented Concept Map Extension) created for the chemistry context [47,48], and the system map [49], which are all adaptations of concept mapping. Other commonly used conceptual modelling and visualisation tools are causal loop diagrams and stock and flow diagrams [26,47].

This paper uses concept maps to visualise complex systems. The tool was chosen because the concept map is a powerful way to visualise connections between elements and the larger whole, composed of those connections [47,50]. Concept maps and their adaptations have been used as tools to observe and assess systems thinking skills [27,50,51,52]. Assaraf and Orion [27] pointed out that using non-hierarchical concept maps gives students more freedom to form patterns and complex linkages between concepts, and thus, to present the nature of complex systems. SOCME-type mapping is non-hierarchical, but it includes a visualisation of the subsystems, which forces the construction of the map in a certain way.

SOCMEs and system mapping have recently been studied as a core practice for learning ST in higher chemistry education [49,51,52]. Szozda and colleagues [52] studied undergraduate students’ ability to model climate systems without prior introduction to ST. They found that students rarely presented the sub-microscopic level in their system maps, and that students presented a range of connections but lacked the circular and causal connections. They also found that causal reasoning was hard to identify from the maps and that the human connection was not present in the maps, perhaps due to the used source material.

3. Methodology

The study employed five semi-structured in-depth interviews as the method to gather data [53]. The five interviewees selected were chemists from academia or industry, working currently or previously on sustainability-related research. The selection of interviewees was conducted to ensure that the sample of interviewees was relevant to the research questions. For this study, three cases from the five interviews were selected to be presented as concept map models. The three cases were selected to give a representative sample of developmental work on chemistry in academia and in industry, presenting the sustainability-related systems and including the element of systems thinking researched. The background information of the three interviewees is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Background information of the three interviewed chemists.

The interviews were semi-structured and in-depth, aiming to give space for the interviewees to speak about their work in their own terms, with a focus on their work’s connection to sustainability and the systems it is related to [53,54]. They were encouraged to speak in a more holistic manner and to connect their work to a range of interconnections. Therefore, each interview is different in its focus and generality and thus each interview is presented according to the data.

The length of each interview varied between 60 and 90 min. The interview was constructed of background questions and six actual interview questions. The interview questions are presented in Appendix A. Some interview questions were provided to with examples, to clarify the meaning of the question. The interviewees were provided with background information about ST, the research questions, and the data protection notice for scientific research two weeks before the interview. The interviews were conducted in 2022 with Zoom video conferencing software. Used version numbers were 5.10.4 (interview with chemist 1), 5.12.6 (interview with chemist 4), and 5.12.9 (interview with chemist 5).

Analysis

Data were transcribed into text and analysed using qualitative content analysis. It is a standard approach in qualitative content analysis for the transcript to be systematically categorised and coded to identify recurring themes or concepts [54]. Analysis was carried out by first identifying the core themes from the interviews as cases. From each case, patterns and relationships between elements were identified according to the interviewees’ descriptions, as they described the case from the perspective of how their work is connected to sustainability advancements and part of larger systems.

The systemic models were conducted in the form of non-hierarchical concept maps describing a certain systemic whole or case, based on the chemistry advancement that the interviewee had worked on. The concepts in the maps were limited to those interviewees mentioned in the interviews, except in concept map 3 (CM3) (see Appendix D) from the first chemist (C1), which includes two additional concepts to enhance the system’s comprehensiveness. The additional concepts are presented as a lighter font and outline. Link words between the concepts were based on the interviewees’ descriptions. After designing the concept map, various aspects and domains were identified and colour-coded.

Lastly, various ST elements (leverage point, delay, and future perspective) were identified from the interviews concerning the defined cases. These were also coded with colours.

Additionally, cyclic behaviour and stock and flow elements were identified from the cases. The stock and flow dynamic was found to not be presentable in the non-hierarchical concept map. Circular connections were identifiable by coloured arrows, but identification of a reinforcing or balancing connection was found to be difficult. Hence, the causal loop diagram presentation was found to be more effective for the presentation of cyclic behaviour.

As mentioned, concept maps were selected as the visualisation tool for the research. The selection was justified for the following reasons:

- Concept mapping is simple and is easy to learn. It is a well-established teaching methodology and is likely to be familiar to pre-service teachers to some degree.

- Concept mapping is a visualisation technique focused on presenting connections between elements, hence it is suitable for presenting the multiple elemental aspect of systems thinking. Concept mapping was found to be an efficient tool for observing and assessing six out of the eight systems thinking abilities listed by Assaraf and Orion (1. identify the components of a system and processes within the system; 2. identify relationships among the system’s components; 3. identify dynamic relationships within the system; 4. organise the systems’ components and processes within a framework of relationships; 5. understand the cyclic nature of systems, and in some cases, extend them; 8. think temporally: retrospections and prediction) [27,50].

- The concept map is a simple format that can be elevated to include aspects of systems thinking, such as delay, leverage points, and future perspectives, that arose from the interviews.

The broad systems related to the first research question were identified according to cases presented in the concept maps, not from the entire interview dataset. The classification of connections as “direct” or “indirect” was based on observations of how immediately the research findings relate to these systems, such as the circular economy. For instance, the connection to the broader systems of the circular economy was declared to be more direct in CM1 and CM3, and less direct in CM2. It is important to note that this classification describes the nature of the connections to the systems being investigated, not the magnitude or significance of the impact on the system.

4. Results

In the results section, each case is first briefly outlined (Table 2) and then results are presented for each research question. The concept maps were created to respond to the RQs, since they effectively illustrate the larger systems and the elements of systems thinking that are present and connected to the interviewees’ work. However, these concept maps and the descriptive explanations are highlighted examples from the data. Full concept maps built up from the interviews are presented only in the electronic material (see Appendix B, Appendix C and Appendix D). The system model presentation is substantive for the representation of actual systemic nature derived from the data.

4.1. Sustainability-Related Systems (RQ1)

Table 3 illustrates the broad systems in which the research work of the chemists is embedded. All of them are working or have worked in developmental research that is advancing circular economy. In two of the cases, the work is also advancing or related to the bioeconomy. One case is advancing the green transition or the change from fossil-based energy systems to electric energy systems. In all the cases, the research could have led to, or has led to, new production, meaning new production facilities such as plants and factories. In one case, the researcher (Chemist 5) was concerned and had an impact as an expert advisor on the national security of supply:

Table 3.

Sustainability-related systems derived from the data. Larger X indicates a direct connection, and small x an indirect connection.

Circular economy:

- Direct connection: Chemist 5 developed new methods to recover and reuse metals, especially REEs.

- Indirect connection: Chemist 4 is developing applications for polymers that are derived from a waste stream.

- Direct connection: Chemist 1 developed new methods for the molecular-level recycling of cellulose fibres, such as cotton clothes.

Bioeconomy:

- Direct connection: Chemist 4 is developing biobased alternatives for fossil-based materials.

- Indirect connection: Chemist 1 is developing ways to recycle biobased materials, so they can be reused.

Green transition:

- Direct connection: Chemist 5 is working on solutions that will partly help secure the availability for materials that are going to have a drastic increase in demand due to green transition.

Emergence of new industrial sector/production:

- Direct connection: Chemist 5 is developing a metal recovery method that will likely lead to new types of recovery plants and production.

- Direct connection: Chemist 4 is researching applications for materials, which will be produced in new production lines of plants if they can be commercialised.

- Direct connection: Chemist 1 has developed a method of a dissolution technique that has led to a new production plant.

National security of supply:

- Direct connection: Chemist 5 possesses influential mechanisms as an expert advisor and has recommended the establishment of a national stockpile for REEs.

4.2. Elements of Systems Thinking That Can Be Presented in Concept Maps (RQ2)

Non-hierarchical concept mapping was found to be a good tool to reveal the complex nature of system chemists’ work in the context of sustainability. Different aspects, such as different domains of sustainability or ST elements, can be demonstrated by colour. However, the limit of presentable elements was found to be limited by the tool which was used, and for the clarity and readability of the map.

As can be observed from the concept maps, many elements of ST can be identified from the chemists’ descriptions of the systemic nature of their work and research in the context of sustainability. From the three cases, the following elements were identified:

- Looking at the larger picture, seeing the network of different elements.

- Identifying components of the system.

- Recognising the interconnections between the parts.

- Identifying leverage points.

- Noticing delay.

- Temporal thinking.

- Cyclic nature.

- Identifying subsystems.

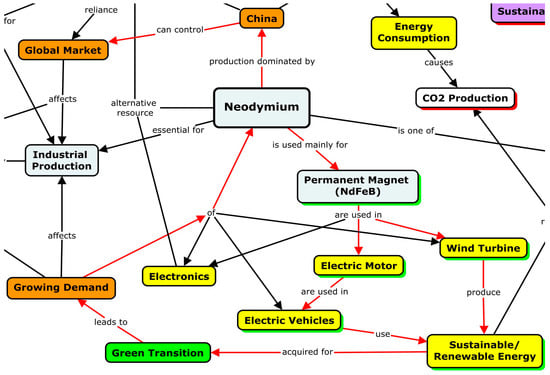

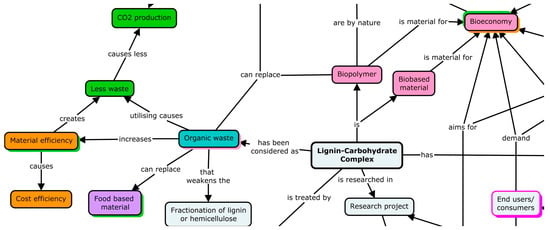

The interviewees gave rich descriptions of the larger whole that their work is part of. They identified many connections that build up the system their work is part of. They described many interconnections between the components that build the dynamic nature of the whole (see Figure 1). For example, from CM1 (the Neodymium Case), the increasing demand for Nd due to green transition may lead to growing dependence on China, which is currently dominating its production.

Figure 1.

Cropped part of CM1, presenting components, interconnections, and circular nature on a concept map.

“…the recovery technologies being developed, for example, the fact that we can demonstrate our capabilities to recover and recycle these specific raw materials, offers a kind of political leverage to the major players in the (global) market.”—Chemist 5

“The Chinese hold a ninety-five percent share in the trade of these metals.”—Chemist 5

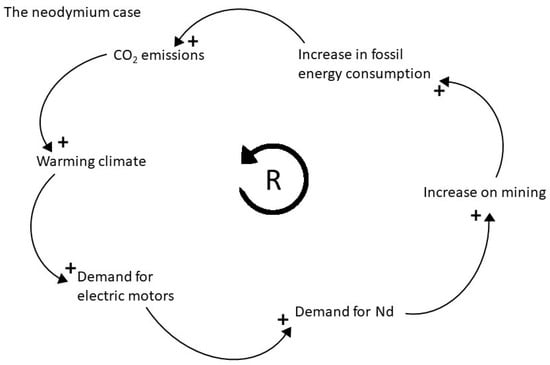

The cyclic nature was identified in CM1, the case of Nd, but was not detected in the other two CMs. In CM1, the cyclic nature was as follows: the increasing need for Nd to constrain CO2 emissions, which may lead to an increase in mining that causes CO2 emissions. This would be a reinforcing cycle. By replacing mining with recovering and recycling, CO2 emissions would be drastically lower, which would create a balancing cycle. Cyclic connections can be presented in the concept map, as in Figure 2. The nature of the connection might not be easy to show in all cases, or it may depend on other connections. Indicating if the cyclic loop or connection is reinforcing or balancing is difficult to show in these maps. Parallel presentations as a causal loop diagram would be the best way to present causal connections found in the system.

Figure 2.

Causal loop diagram presentation of the cyclic nature of the system.

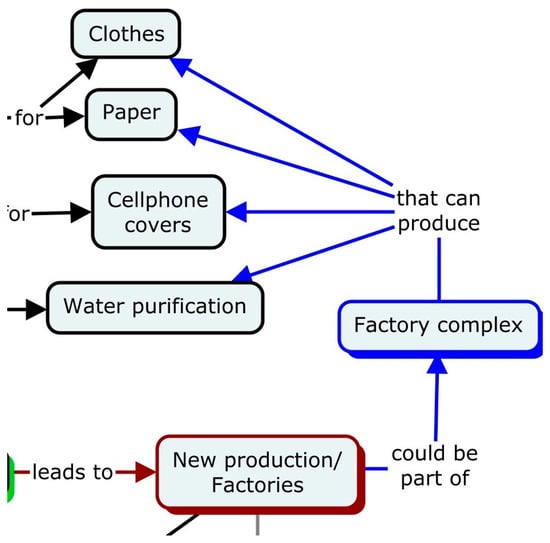

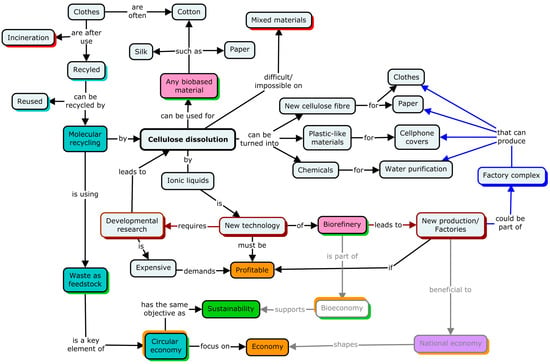

Temporal thinking was identified in all three cases, as the interviewees did depict future scenarios as desirable or having alarming trajectories. However, these future trajectories were found to be difficult to present clearly in the concept maps, excluding Chemist 1, who depicted an exceptionally clear future scenario or “utopia” for new production lines (Figure 3). This was identified in blue in CM3.

Figure 3.

Blue arrows and outline used to present the future scenario in CM3.

“…if there is a system in place that performs cellulose dissolution from, say, paper pulp, there could be another line that aims at chemical modification, meaning that it could produce, for example, water purification chemicals or possibly something resembling plastic, like mobile phone cases. But it’s still utopian that all these could be realised.”—Chemist 1

Stock and flow dynamics can be identified in the cases, such as the description regarding materials and CO2, where flow stacks up. However, they were not found to be adaptable to concept map presentation.

Emergence was not identified from the interviews.

Delay was indicated by the interviews with narrations of the duration and phases related to developmental work, establishment of infrastructure, and changes in directives and laws. They were presented in concept maps with a dark red outline and arrows (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Dark red arrows and outline were used to indicate the delay on the system. CM3.

The excerpt below is an example of researchers’ understanding of a delay in the developmental process. The interviewee reflects on the timeframes of product development processes within the context of sustainability-related applications. They used a conversation with an industry representative as an example, during which they emphasised the realistic time challenges of commercialising a new idea.

“My response highlighted the long-term nature of such developments, suggesting that we were looking at a timeline spanning perhaps five, ten, or even 20 years into the future. This was a candid way of grounding the conversation in realism, without making premature promises about the feasibility of our project. Yet, it also reflected a belief in the potential of our idea.”—Chemist 1

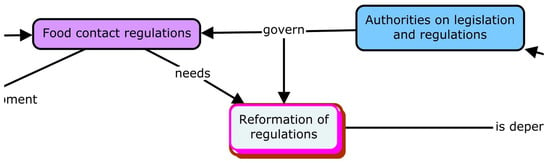

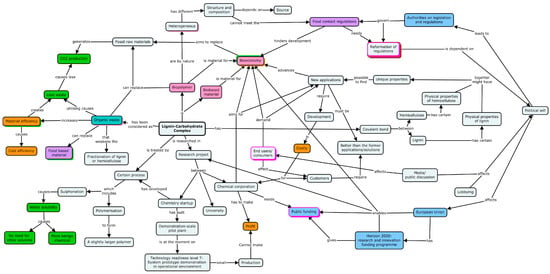

Leverage points of the system were identified as well, but only in CM2. These were coded with a pink colour (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

A pink outline was used to indicate leverage points on CM2.

“Current regulations, for instance, from the perspective of product safety, are also significantly insufficient when it comes to biopolymers. They have been constructed with requirements meant for synthetic products, making it virtually impossible for biopolymers to comply. As such, the regulation concerning product safety must evolve concurrently as biopolymers emerge, necessitating the construction of new specifications. And yet, this change is notably slow to materialise.”—Chemist 4

Subsystems were not identified in these maps. Instead, sustainability domains such as environmental (dark green), economic (orange), and social sustainability (lilac) and other themes such as the circular economy (turquoise), the bioeconomy (light pink), green transition (bright green), energy solutions (yellow), and public authorities (light blue) were identified by colour. An example of a few of the three domains and a few themes indicated by colour is presented in Figure 6. Using colours instead of divided sections for subsystems gives more freedom to construct the concept map and emphasises the different points of view in sustainability considerations.

Figure 6.

Example of the colour coding from the CM2. Environmental sustainability aspects were indicated with green colour, social sustainability aspects with lilac, economic aspects with orange, and circular economy-related aspects with turquoise.

5. Discussion

The aim of this paper was to explore firstly what sustainability-related systems chemists’ developmental research is connected to, and secondly, the opportunities for conducting concept map presentations of developmental work on sustainability solutions from authentic chemistry researchers’ descriptions.

5.1. Sustainability-Related Systems

Firstly, broader systems related to sustainability were observed. Researchers’ descriptions revealed two predominant trends in sustainable development: the bioeconomy and the circular economy. Three examples provided a comprehensive overview of both trends’ key perspectives: CM1 highlighted the significance of recycling in counterbalancing the monopolisation of global trade, thus promoting regional production independence; CM2 discussed the use of side streams as starting materials for biomaterials, and the need to replace food-derived materials with other biobased starting materials; and CM3 explored the recycling of biobased materials along with its associated constraints and opportunities. Chemist 5 also introduced the concept of the green transition, which pertains to transforming energy production and usage towards renewable and electric-based solutions. A notably intriguing aspect emerged from Chemist 5, as highlighted in CM1: the national security of supply. This concept is fundamental to ensuring the uninterrupted functioning of society’s critical services, thus constituting an essential element of social sustainability. The chemical industry plays a pivotal role in this context, as many of its operations are integral to these critical functions. By safeguarding the supply chain of essential chemicals, the industry not only underpins various sectors such as healthcare and manufacturing but also ensures economic stability during crises. Consequently, this aspect not only enhances the industrial perspective but also connects research and production in chemistry to the broader functionality of society.

Ultimately, all cases highlighted the potential for a new type of industrial production. Notably, only Chemist 1 (CM3) emphasised that the establishment of a new production plant is significant and valuable, contributing to economic prosperity and job creation, which in turn supports social sustainability by fostering societal well-being. While other cases acknowledged new production initiatives, they primarily focused on the means to produce new, more sustainable products or materials. It is important to note that although Chemist 1 did not explicitly articulate the benefits of new production facilities, the discussion suggested that their mere existence is considered valuable and desirable.

5.2. Elements of Systems Thinking

Earlier concept map adaptations in ST education primarily focused on depicting only the concepts and their interconnections and used complementary exercises to reveal other aspects of ST [27,50]. The SOCME extension included the display of subsystems illustrating the important aspects of boundaries of systems and interconnections between systems themselves [47,48]. Under the name of system mapping, other inventive and convenient approaches have been developed, such as exploring the connections of the system components to SDGs [49,55].

Concepts or components of the system related to the developmental work of the sustainability solution were identified directly from the interviews, except two concepts added to CM3. Identifying the relevant concepts was found to be easy, after the case was confined. This paper presents three different cases, from which CM2 is very broad and CM1 and CM3 are more limited. The complete concept maps can be found in the Appendix A, Appendix B, Appendix C and Appendix D. The extent of the map was connected to how focused the interviewees’ descriptions were. Chemist 4, from whom the CM2 was conducted, explained one case in more detail, while Chemist 1 and Chemist 5 spoke at a more general level and explained various cases.

The connections were identified according to the explanations of the interviewees, not derived directly from their descriptions. The interconnections and complex nature of the cases are well presented in the concept map type of the concept model, but the complexity of the maps was not evaluated, since all three cases were different, and all the possible connections were not presented to secure the readability of the maps. Complexity could be evaluated by verifying the number of linkages between concepts [27,50,52].

Complexity is a key aspect of ST, yet it is crucial to emphasise the identification of effective tools for its depiction, communication, and understanding, rather than merely striving to create overly complex models. In employing concept maps, this requires particular attention to the relevance of connections, their quality and rationale, as well as the clarity and readability of the overall map. Such an approach aids students in understanding how individual components interconnect within broader systems, thereby fostering a deep comprehension of complex systems. Additionally, articulating the linking words should be emphasised, as this represents a significant challenge for students when constructing concept maps [27].

The direction of the connections can also be evaluated when assessing concept maps [52]. In these cases, it was observed that at certain points, the link could be interpreted in either direction, but the accuracy was ultimately determined by the description of the connection. Once again, the clarity and readability of the map should be emphasised.

Szozda and colleagues [52] identified a lack of circular connections in students’ system maps. In this study, only one of the three cases featured circular connections. This might suggest that the interviewed chemists do not intuitively recognise circular connections and feedback loops, or that these are not prevalent in the developmental processes viewed as systems. Circular connections can be displayed on the concept map, but a complementary assignment would be advisable. A causal loop diagram is the optimal method for presenting these connections, although it generally requires a more confined scope. Additionally, Szozda and colleagues [52] found that the causality of connections was challenging to determine solely by the link words and arrows, suggesting that an additional assignment to clarify causality in a causal loop diagram might be beneficial.

This study demonstrates that additional fundamental elements of ST can be identified and effectively presented in a concept map. These elements include delays, leverage points, and future scenarios. Delays were commonly noted, as interviewees frequently mentioned the duration of certain processes in developmental work. For instance, the lengthy process of scaling up production through Technology Readiness Levels prominently illustrates how scientific advancements can impact society after considerable delays. Other noted delays included the establishment of infrastructure, such as new production lines or industrial plants, and legislative changes in food contact regulations, which are typically slow to implement.

Leverage points were specifically identified in one case, CM2, where Chemist 4 clearly outlined three leverage points that could drastically alter the system developing new biobased materials: public funding, end-user, or consumer demand, and the updating of food contact legislation unsuitable for heterogeneous biobased materials.

Only Chemist 1 in CM3 identified a clear future scenario involving several parallel production factories or lines for products based on recycled cellulose material. Illustrating future scenarios in concept maps is often challenging; thus, including them as a complementary exercise is advisable.

The stock and flow aspects were also examined as they are central to ST [7,26], though they were not found to be adaptable to concept map presentations. Emergence, the phenomenon caused by the dynamic structure of the system, was not identified from the interviews.

Different aspects of sustainability were indicated with colours, a method comparable to identifying subsystems in SOCME [47,48], as utilised by Reynders and colleagues [51] who categorised ecological, economic, and societal domains as subsystems. In this study, aspects and domains of sustainability were derived from the concept maps, not directly from the interviewee’s descriptions. The three domains—ecological, economic, and social—were identified alongside aspects like circular economy/recycling, bioeconomy, energy solutions, and green transition.

Furthermore, components with a clearly negative impact on sustainability were highlighted in bright red. Categorising individual aspects as positive or negative in terms of sustainability is not a straightforward task, and they should be evaluated within the context of the overall system. For instance, in the case of CM1, it is the environmental damage and potentially poor working conditions, rather than the act of mining itself, which are of concern. Nevertheless, mining can also be viewed as fundamental to produce technology essential for the green transition and as a driver of economic growth.

If reflecting on York and Orgill’s [42] framework of ST learning objectives for chemistry education, the concept map adaptation based on the authentic narrative of chemists’ developmental work can meet four out of five objectives to some extent. The dynamic system and emergent behaviour were not found representable in any extent in concept maps. However, this study expands on York and Orgill’s initial objectives by adding two ST elements: leverage point and delay.

These three cases neatly demonstrate how an authentic narrative can provide a holistic description of real-world contexts in chemistry. Chemists’ descriptions included various factors and viewpoints across all three domains of sustainability, offering a realistic understanding of how advancements in chemistry are developed and advanced. Moreover, they provide complex explanations of the problems and solutions concerning sustainability issues they are describing. However, as these are individual cases, the findings cannot be generalised. There is a variety of descriptions across the three cases examined. It can be stated that the researchers’ own descriptions are rich and provide multiple perspectives, incorporating various elements of ST.

As the literature indicates, there is a significant need for economic and industrial perspectives in chemistry education [21,22]. All three cases offer insights into economic and industrial operational aspects. Economic viewpoints were variously highlighted, for example, Chemist 1 and Chemist 4 emphasised profitability as a key enabler of solutions. Chemist 1 noted that the circular economy could be viewed as an attempt at sustainability through economic systems, linking profitability to individual stakeholders, such as retailers needing to sell their products. Chemist 4 noted that using residue materials, previously seen as waste, can reduce costs. They also mentioned that despite pressure from end-users to adopt “greener” and more sustainable solutions and biobased materials, any new material must be considerably better or cheaper than existing ones. Chemist 5 offered a different perspective; their developmental work relates to the recycling of REEs and other metals, noting that as the green transition progresses, the demand for these materials increases, impacting global trade. Most of the production of REEs is dominated by China, making these materials increasingly vital for industry and raising questions about the sufficiency of national supply and the need for stockpiling, thus underscoring the economic significance of metal recycling and its impact on industry and society.

How can this approach be best adapted to chemistry education? How can we source similar material to these extensive interviews? Central to this discussion is the chemists’ own narratives about the development of new solutions. Ideally, materials for such exercises might include expert quest speakers or interviews conducted by students. If this is not possible, podcasts and other media interviews in scientific programs could serve as a good source material. Magazine articles, while sometimes less detailed, can also serve as real-world teaching material that provides an authentic insight into a chemist’s work.

To achieve the intended learning outcomes, the guest speaker or interviewer should be informed about the outline and purpose of the presentation or interview [30]. Specifically, they should be made aware of the aim to understand how the research integrates into larger societal systems, including economic perspectives and other relevant aspects.

From these observations, it can be derived that creating a concept map from an authentic narrative is a highly subjective process. As a learning exercise, this might pose difficulties, particularly from a quantitative assessment perspective. For example, when using an authentic narrative, it might be difficult to determine what entity should be defined as the system examined and how many connections there should be in total. Therefore, the assessment should be more concerned about the reasoning behind the system, leading to the conclusion that a concept map exercise should always be accompanied by a written or oral presentation of the map. As concept mapping is inherently subjective and should be used to present a broader picture of the interplay of different components and perspectives, comparing more than one concept map derived from the same material might be a highly valuable approach.

With just three cases, a very broad picture was uncovered. While this extensive exploration aligns with the core objectives of systems thinking, it presents challenges in the classroom setting, particularly when the themes are not derived from the teacher but from an expert. Such exercises necessitate a critical thinking approach, which can be fostered through reflective discussion in the classroom [31]. In this context, systems thinking is employed to understand complex wholes rather than to ascertain objective truth. It is vital for students to recognise that, although the expert possesses a deep understanding of the factors influencing the developmental work they discuss, their perspective remains subjective. To highlight this aspect, it would be reasonable to explore potential values and attitudes that the expert might hold, such as prioritising economic growth, advocating for climate change prevention, or endorsing technological solutionism. Yet, this is the very aspect of the approach that makes it advantageous for sustainability education, such as exploring the controversial social issues, many perspectives they hold, and learning critical thinking in the context of sustainability [16,17,18].

This methodology may not fully depict the developmental work’s macro-level connections to broader society, industry, economy, and the sub-microscopic level. However, the question remains: is such depth imperative in every chemistry lesson? These examples demonstrate the complex reality in which new technologies and applications are developed for a more sustainable way of life. They also illustrate the system we currently live in. While this might not be the core of educational objectives in chemistry, where else could they then be presented? Understanding the whole, including the different domains and perspectives, is fundamental to sustainability education [16,17,18]

In conclusion, this study underscores the broader role of chemistry within the complex system of sustainability, emphasising its interactions with social, economic, and political factors. By employing systems thinking, we equip students with the skills necessary to understand and navigate these interconnected issues, thereby contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of chemistry’s essential role in modern society and sustainability efforts. This approach is instrumental in preparing students for their future roles as professionals and informed citizens, ready to face and address real-world sustainability challenges.

This approach needs more research on how best to implement it into teaching. One important area of chemistry education that needs more research on ST is chemistry teacher education [25]. This could be an apt method for pre-service teacher education to present the contemporary topics of sustainability in chemistry; the crosscutting nature, perspectives, and domains of sustainability; understanding the connections of chemistry to broader society and industry; and, of course, learning ST.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated the integration of ST into chemistry education by modelling the system of developmental work on sustainability solutions in chemistry, based on descriptions from chemists. The modelling tool employed was a non-hierarchical concept map. The objectives were (1) to explore the broader systems related to chemists’ work and (2) to assess the potential of concept mapping in reflecting the skills and elements of ST most relevant to chemistry education, along with three additional fundamental elements of ST.

The study found that the chemists described some broad systems that their work was part of; notably, the circular economy and the bioeconomy were central to their descriptions. Other less obvious systems were also identified, including the green transition, the national security of supply, and the emergence of new industrial sectors or production. In terms of the objectives of sustainability education in chemistry, authentic descriptions provided a rich illustration of the systemic nature of chemists’ work and its connection to broader societal systems.

Non-hierarchical concept mapping proved to be an effective tool for ST modelling in the context of developmental work on sustainability solutions. Eight elements of ST were notably represented in the non-hierarchical concept maps to varying degrees. These elements were the following: (1) viewing the larger picture and recognising the network of different elements; (2) identifying components of the system; (3) recognising the interconnections between the parts; (4) understanding the cyclic nature; (5) identifying leverage points; (6) recognising delays; (7) employing temporal thinking; and (8) identifying elements and domains of sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, E.V., M.A., and J.P.; Data curation, E.V.; Formal Analysis, E.V.; Funding acquisition, E.V. and M.A.; Investigation, E.V.; Methodology, E.V., J.P. and M.A.; Project administration, E.V.; Supervision, J.P. and M.A.; Validation, E.V.; Visualisation, E.V.; Writing—original draft, E.V. and J.P.; Writing—review & editing, E.V., J.P. and M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Finnish Cultural Foundation, grant number 00231229 and University of Helsinki.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it was conducted with adults and did not involve any ethically sensitive topics. The Finnish National Board on Research Integrity does not recommend ethical evaluation for this type of research setting, and the Ethical Committee of the University of Helsinki does not require a review when there are no ethical concerns to address. All participants were informed about the research and provided their informed consent prior to participating in the study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data have been anonymized but are not publicly available because of the privacy issues related to the qualitative nature of it.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Interview Questions

The six interview questions were as follows:

- How is sustainable chemistry, or sustainability more broadly, related to or connected with your job or research?

- How is the specific research topic selected?

- How do you define your work community?

- Do any external parties have a direct or indirect impact on your work within your work community?

- In what situations do you use systems thinking in your work?

- What kinds of systems is your work involved in?

Appendix B. Concept Map 1—Case of Neodymium

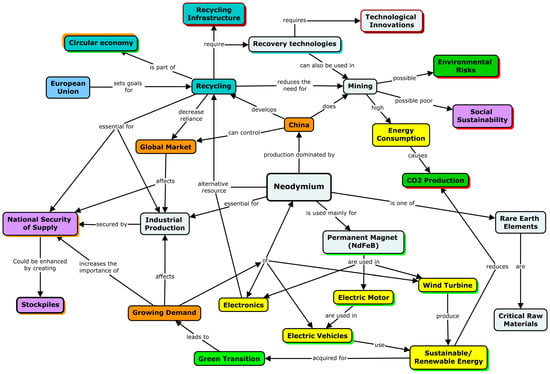

The first concept map (CM1) depicts the case of Neodymium, Nd (Figure A1). CM1 arises from an interview with Chemist 5 (C5), a professor and leader of a research project focused on recovering metals from electronic waste. This waste contains numerous metals identified as critical raw materials by the EU, particularly rare earth elements (REEs). To illustrate the significance of this research in the context of sustainability and its integration into larger systems, C5 chose Nd as an example.

“Over the last year, there has been a dramatic change, especially at the level of the European Union, awakening to the fact that these are, in fact, a group of metals whose availability must be secured in one way or another.”

Nd, as an example of one of the REEs, has various applications. C5 highlights the use of Nd as permanent magnets, in wind turbines, electric motors, and other electronic devices. Wind energy and electric vehicles are not only prevalent energy solutions but also crucial components of the green transition. As such technologies gain traction, the demand for specific materials, including neodymium, increase significantly.

“As an example, the recovery of rare earth metals from permanent magnets could be mentioned; these are the metals that are widely used in various contexts, including in wind turbines which utilize neodymium-iron-boron magnets. Similarly, such metals can also be found in mobile phones.”

“However, without electric motors that contain powerful magnets, those electric cars wouldn’t go anywhere, regardless of how good the batteries are.”

C5 stresses the criticality of raw materials like neodymium for national and European industries, rendering its accessibility vital for national security of supply. The national security of supply could be enhanced by creating stockpiles of certain critical metals. With Europe devoid of neodymium-producing mines, it relies on global markets for the material. China’s dominance in neodymium, among other REEs, production allows it to influence the material’s global price significantly.

“…to meet the needs of the industry so that there would be enough, and then indeed, this aspect of security of supply and availability. I have been strongly involved in advocating for the creation of stockpiles for certain metals…”

“…the recovery technologies being developed, for example, the fact that we can demonstrate our capabilities to recover and recycle these specific raw materials, offers a kind of political leverage to the major players in the (global) market.”

“The Chinese hold a ninety-five percent share in the trade of these metals.”

C5 notes that mining activities significantly impact the environment, particularly through CO2 emissions, and affirms that mining efforts are frequently linked with substandard working conditions. Consequently, C5 advocates for the robust recycling of neodymium. While recycling may not meet the rising demand for neodymium, it is imperative to ensure no wastage. Advancements in recycling technologies contribute to the circular economy’s objectives. Nevertheless, before these innovations can be implemented, the necessary infrastructure, production facilities, and supply chains require planning and construction.

“It has been estimated that, for instance, when comparing carbon dioxide emissions from the developed process, where we dissolve electronic scrap with acids and recover metals through a hydrometallurgical process, the carbon dioxide emissions from recycling those metals are just 5% of what they would be for metals extracted from virgin mineral resources.”

Figure A1.

Concept map 1 based on the interview with Chemist 5 is colour-coded in the following manner: yellow—energy connection; dark green—ecological sustainability; bright green—green transition; lilac—social sustainability; orange—economical aspects; light blue—public authority; turquoise highlight—circular economy; red—potentially harmful consequences; dark red highlight—delay.

Appendix C. Concept Map 2—Case of Lignin–Carbohydrate Complex

Concept map 2 (CM2) based on the interview with Chemist 4 (C4) (Figure A2) is colour-coded in the following manner: dark green—ecological sustainability; lilac—social sustainability; orange—economical aspects; light blue—public authority; turquoise highlight—circular economy connection; pink highlight—leverage point in the system.

Public funding, end-users/consumers, and reformation of regulations are marked as leverage points (pink highlight) in the concept map, because they are mentioned as elements that have the power to drive the progress of the bioeconomy.

The second concept map (CM2) represents the case of a research project on the lignin–carbohydrate complex, as discussed in the interview with C4. This broader map outlines the motivations, prerequisites, and challenges associated with the development of new biomaterials. The research, a collaborative effort between a chemistry startup and a large corporation, includes C4′s doctoral work under university supervision and is financed by the EU’s Horizon 2020 programme.

The lignin–carbohydrate complex, a natural constituent of biomass, has formerly been regarded as a waste product, its presence seen as a hindrance to the separation of hemicellulose and lignin. C4 notes that in this complex, lignin and hemicellulose are conjoined by a covalent bond and hence possess the properties of both. Due to these combined properties of hemicellulose and lignin, the complex could possess unique characteristics leading to new innovative applications. C4 further remarks that the precise structure of the polymer molecule is contingent upon the biomass source.

The project revolves around a polymer derived from the lignin–carbohydrate complex, produced through a polymerisation process pioneered by the startup. C4 details the sulphonation of this polymer, rendering it water-soluble, and explains that polymerisation results in a marginally larger molecular structure. Working for a large chemical corporation, C4 is tasked with identifying suitable uses for this novel biopolymer.

From a sustainability perspective, the research aims to harness biomaterials, particularly ones previously classified as waste, thereby reducing waste generation, reducing CO2 emissions, enhancing material efficiency, and therefore cutting costs. The objective of replacing fossil-based materials aligns with bioeconomy goals. Furthermore, C4 emphasises that this new polymer could substitute starch in various applications, offering a more sustainable alternative given starch’s origin as a food-based material.

“The ability to utilize raw materials more efficiently would bring cost-effectiveness to the process, generate more revenue, reduce carbon footprint, and decrease waste. And it would create something new. A biopolymer that could potentially replace polymers made from fossil sources or, in this case, starch in our project. In fact, this works in many of the same applications as starch, and we think that starch comes from the food chain.”

The sulphation process renders the polymer water-soluble, thereby obviating the need for other, potentially more hazardous solvents. Moreover, water-soluble chemicals are generally more benign for the environment.

As materials produced by the chemical company may be used in food contact, they must comply with food contact regulations. C4 highlights the challenges posed by these regulations, which are tailored to synthetic materials and do not accommodate the inherent heterogeneity of biomaterials. This heterogeneity, resulting in trace amounts of other substances, contrasts with the homogeneity of synthetic materials. According to C4, this discrepancy presents a substantial barrier to the broader acceptance of biomaterials. They advocate for the reformation of food contact regulations to facilitate the bioeconomy’s expansion.

C4 underlines the need for public funding, such as the EU’s Horizon 2020 project, for propelling the bioeconomy forward, stating that such initiatives would be untenable without it due to the high costs and the imperative of profitability. Although there is consumer demand for more sustainable options, new products must outperform or undercut existing ones to gain customer adoption. Until production can be amplified to meet industrial demands, the corporation is unable to market the product due to insufficient supply.

“From the perspective of a chemistry corporation, our clients are so large that our current production capacity wouldn’t suffice for us to start selling this product. The corporation joined this project because we received funding from the EU. This research is just the first step; once we prove its viability, we need to think about how to scale up production and deliver it to customers. No one has ever heard of such things as this biopolymer while starch or synthetic products we use, which are incredibly cheap. They’ve been in use for decades. This is part of a broader bioeconomy program, and such initiatives are needed for companies to dare to test and advance high-risk research. External funding is necessary. This isn’t yet a ready business case, but it’s an ideal research topic and a perfect subject for industry-academic collaboration and even a thesis.”

Finally, C4 notes the significance of media presence and lobbying in promoting bioeconomy progress. These efforts exert pressure on policymakers and enhance public awareness of sustainable advancements, thereby spurring companies towards reform.

Figure A2.

Concept map 2 based on the interview with Chemist 4 is colour-coded in the following manner: dark green—ecological sustainability; lilac—social sustainability; orange—economical aspects; light blue—public authority; turquoise highlight—circular economy connection; pink highlight—leverage point in the system.

Appendix D. Concept Map 3—Case of Cellulose Dissolution

Concept map 3 (CM3) is based on the interview with Chemist 1 (C1) (Figure A3), who approaches sustainability in their work in a more general manner. They explain that sustainability is quite a vague term for research in chemistry, as it does not have a common definition but is often understood as green chemistry which seems to restrict it mainly to certain ways of conducting chemistry. They point out that the circular economy, on other hand, seems to have the same objectives as sustainable development, but it is more focused on economic aspects. C1 explains that for a chemist, anything can be a raw material, and molecular recycling is a good and sensible goal. Nothing should be wasted, and things should be made to last. But on the other hand, the constraint comes from the cost of reusing the material, in short, how efficiently the material can be reused. They go on explaining that it is not enough that something can be reused, it must be profitable and cheap enough for consumers to favour it, too.

“From a chemical standpoint, there are no wastes, only raw materials that may be challenging, such as carbon dioxide, if considered an emission. Yet, it is an excellent starting material for various applications, but then we encounter a scale problem: whether it can be utilized on a sufficiently large scale and how this can be achieved. Part of the challenge arises from the fact that we could start building a society that forgets all fossil fuels, but that comes at a high cost. It costs much more than the materials we are accustomed to today, and it means that sustainability comes into play, where things need to be genuinely sustainable and recyclable. Not just because of their cost, but because a disposable culture might not be a good idea from a chemical perspective, and this is exemplified by for instance, our work with textiles.”