Facilitators of Success for Teacher Professional Development in Literacy Teaching Using a Micro-Credential Model of Delivery

Abstract

1. Introduction

Literature Review

- What teaching tools used in an online micro-credential course for teachers were facilitative of learning? Namely, the learning platform and online teaching sessions used in the course.

- What are the challenges and facilitators of success to implementing an online teacher micro-credential at a national level?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context for the Current Study

2.2. Micro-Credential Course Design

2.3. Course Teaching Tools

2.3.1. Online Learning Platform (Learn)

2.3.2. Zoom Online Teaching

2.4. Participants

2.5. Measures

2.6. Data Analysis

2.6.1. Quantitative Questions

2.6.2. Qualitative Responses

3. Results

3.1. Teaching Tools Facilitative of Learning

- Teaching exemplar videos (1330 points);

- Teaching resources (1228 points);

- Videos that taught theoretical content (1037 points);

- Explanatory documents (891 points);

- Online quizzes (549 points);

- Journal research articles and other readings (488 points).

- The ability to revisit videos and resources multiple times (1096 points);

- The organization of teaching content into modules (971 points);

- The ‘24/7’ nature of access to content (904 points);

- The ability to track progress through the course (665 points);

- Other (309 points).

- The order the content was presented in across the weeks (1925 points);

- Being able to view the Zoom recording later (1908 points);

- Having related sections on Learn highlighted (1536 points);

- Connecting with the UC teaching team (1443 points);

- Hearing other teachers’ questions (1228 points);

- The ability to ask questions in a live forum (1156 points);

- Hearing other teachers’ successes (889 points);

- Special guest sessions (881 points);

- Other (284 points).

3.2. Challenges and Facilitators of Success

4. Discussion

4.1. Completion of the Micro-Credential Was a Positive Experience and Supported Teaching Practice

4.2. An Online Learning Platform Provided a Flexible Means of Accessing the Content

4.3. Online Teaching Sessions Are a Key Element of an Online Course

4.4. Challenges of Completion Are Varied

4.5. Implications for Practice

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Demographic Information | ||

| Which micro-credential course did you complete your training in? |

| Single-choice question |

| Where do you live? |

| Single-choice question |

| What is your undergraduate qualification in education/primary teaching? | Open-text response | |

| How long ago did you gain your undergraduate qualification in education/primary teaching? |

| Single-choice question |

| Please list any other tertiary-level qualifications you hold relating to teaching, education and/or literacy. | Open-text response | |

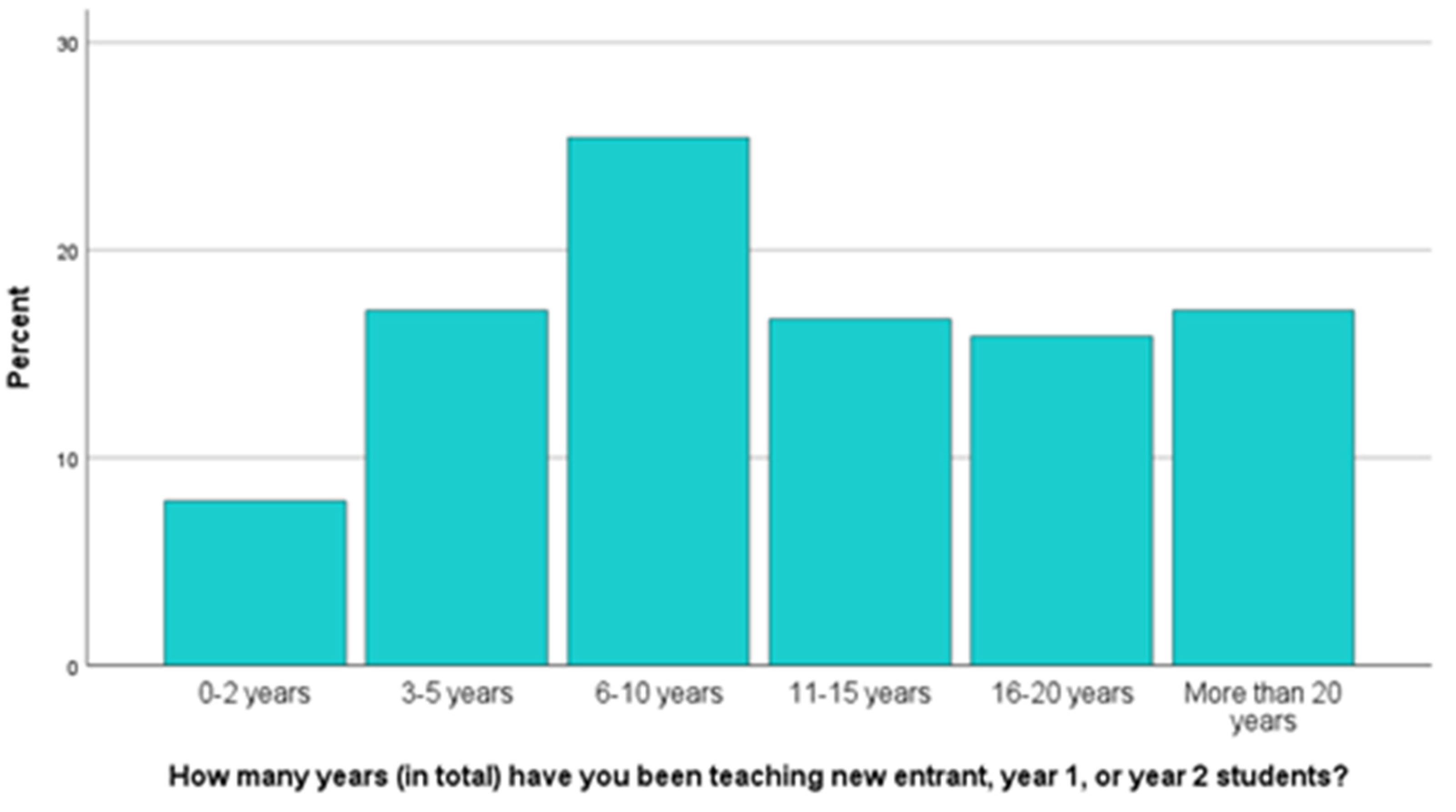

| How many years (in total) have you been teaching or working with new entrant year 1 or 2 students? |

| Single-choice question |

| Over the past 3 years, what are the main ways you have accessed continuing education about literacy education? | Open-text response | |

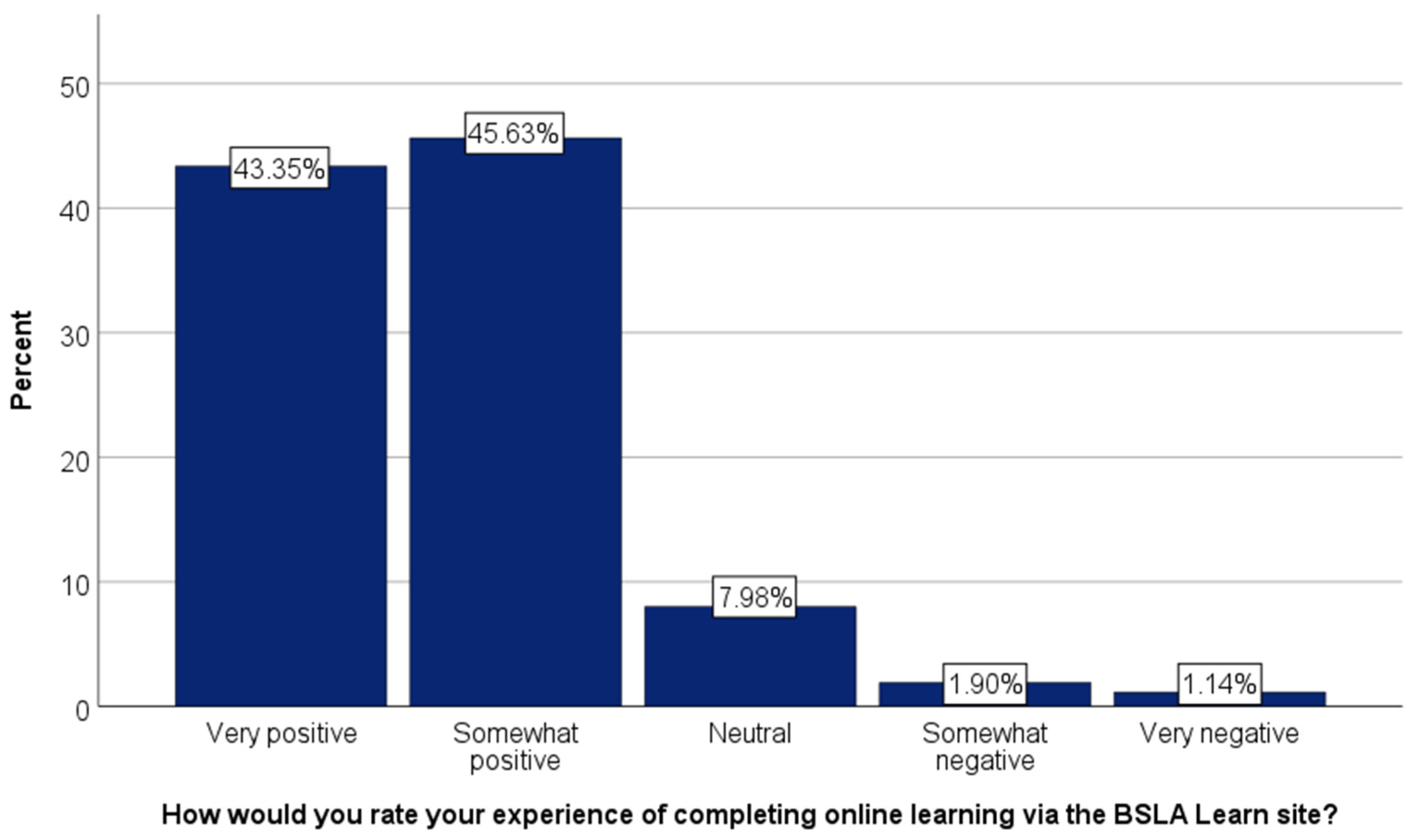

| Learn Course | ||

| How would you rate your experience of completing online learning via the Better Start Literacy Approach Learn site? | Likert scale |

|

| What aspects of the Learn site did you find most useful to support your learning? | Multiple choice |

|

| What aspects of the Learn site did you find most useful? |

| |

| Please add any further comments about the Learn site. | Open-text response | |

| Zoom Teaching | ||

| How would you rate the online Zoom sessions to support your learning? | Likert scale |

|

| What aspects of the Zooms did you find most useful to support your learning? | Multi choice |

|

| Please add any further comments about the Zoom sessions. |

| |

| Micro-Credential | ||

| What were your overall thoughts about the micro-credential training? You may like to comment on the content, structure, assessment tasks, resources and delivery of this training. | Open-text response | |

| What do you feel were the most challenging aspects of the micro-credential training? | Open-text response | |

| What do you feel were the most beneficial aspects of the micro-credential training? | Open-text response | |

| How likely are you to complete further training via a micro-credential model? |

| |

| How likely are you to recommend the Better Start Literacy Approach micro-credential to other colleagues? |

| |

References

- Morrisroe, J. Literacy Changes Lives 2014: A New Perspective on Health, Employment and Crime, National Literacy Trust. 2014. Available online: https://literacytrust.org.uk/research-services/research-reports/literacy-changes-lives-2014-new-perspective-health-employment-and-crime/ (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Bynner, J. Lifelong Learning and Crime: A Life-Course Perspective; National Institute of Adult and Continuing Education (NIACE): London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Crotty, K. Low Health Literacy and Health Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, M.; Conlon, G. The Impact of Literacy, Numeracy and Computer Skills on Earnings and Employment Outcomes; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stanford, E. Transforming How Our Children Learn to Read. Available online: https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/transforming-how-our-children-learn-read (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Pondiscio, R. Can Teaching Be Improved by Law? At Least Twenty States Passed or Considering Measures Related to the Science of Reading. Available online: https://www.educationnext.org/can-teaching-be-improved-by-law-twenty-states-measures-reading/ (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- NZQA. Micro-Credential Listing, Approval, and Accreditation. New Zealand Qualifications Authority. Available online: https://www2.nzqa.govt.nz/tertiary/approval-accreditation-and-registration/micro-credentials/ (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Wheelahan, L.; Moodie, G. Gig qualifications for the gig economy: Micro-credentials and the ‘hungry mile’. High. Educ. 2022, 83, 1279–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, R.M.; Leder, H. An Assessment of Micro-Credentials in New Zealand Vocational Education. Int. J. Train. Res. 2022, 20, 232–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teaching Council of Aotearoa New Zealand. “Professional Growth Cycle” Teaching Council of Aotearoa New Zealand. Available online: https://teachingcouncil.nz/professional-practice/professional-growth-cycle/ (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Standards for Teachers’ Professional Development. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a750b16ed915d5c54465143/160712_-_PD_Expert_Group_Guidance.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- OECD. Education at a Glance 2022; OECD: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, L.; Hyler, M.E.; Gardner, M. Effective Teacher Professional Development; Learning Policy Institute: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher-Wood, H.; Zuccollo, J. Evidence Review: The Effects of High-Quality Professional Development on Teachers and Students. 2020. Available online: https://epi.org.uk/publications-and-research/effects-high-quality-professional-development/ (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- Bartz, D.E.; Kritsonis, W.A. Micro-credentialing and the individualized professional development approach to learning for teachers. Natl. Forum Teach. Educ. J. 2019, 29, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, F.; Charteris, J.; Adlington, R.; Rizk, N.; Fletcher, P.; Reyes, V.; Parkes, M. Developing, situating and evaluating effective online professional learning and development: A review of some theoretical and policy frameworks. Aust. Educ. Res. 2019, 46, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Teachers Know Best: Teachers’ Views on Professional Development; ERIC Clearinghouse: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Moats, L.C. Teaching Reading Is Rocket Science: What Expert Teachers of Reading Should Know and Be Able to Do. Am. Educ. 2020, 44, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Mahar, N.E.; Richdale, A.L. Primary teachers’ linguistic knowledge and perceptions of early literacy instruction. Aust. J. Learn. Difficulties 2008, 13, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, J.; Gillon, G.; McNeill, B. Explicit Phonological Knowledge of Educational Professionals. Asia Pac. J. Speech, Lang. Hear. 2012, 15, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding-Barnsley, R. Australian pre-service teachers’ knowledge of phonemic awareness and phonics in the process of learning to read. Aust. J. Learn. Difficulties 2010, 15, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfeld, S.; Snow, P.; Eadie, P.; Munro, J.; Gold, L.; Orsini, F.; Connell, J.; Stark, H.; Watts, A.; Shingles, B. Teacher Knowledge of Oral Language and Literacy Constructs: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial Evaluating the Effectiveness of a Professional Learning Intervention. Sci. Stud. Read. 2021, 25, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillon, G.; McNeill, B.; Scott, A.; Gath, M.; Furlong, L. Advancing teachers’ linguistic knowledge through a large-scale professional learning and development initiative. Ann. Dyslexia, Unpublished work. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Borland, J.; Moylan, A.; Dove, A.; Dunleavy, M.; Chachra, V. Impacts of microcredentials on teachers’ understanding of instructional practices in elementary mathematics. Education 2022, 22, 475–510. [Google Scholar]

- Purmensky, K.; Xiong, Y.; Nutta, J.; Mihai, F.; Mendez, L. Microcredentialing of English learner teaching skills: An exploratory study of digital badges as an assessment tool. Contemp. Issues Technol. Teach. Educ. 2020, 20, 199–226. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, J.A.; Richard, R.J.; Osman, S.; Lowrence, K. Micro-credentials in leveraging emergency remote teaching: The relationship between novice users’ insights and identity in Malaysia. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2022, 19, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Chen, J. Using Micro-Credentials to Promote Effective Teacher Professional Development: A Case Study from Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University. In Proceedings of the 14th Asian Adult Education Conference, Norman, OK, USA, 1 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasia, M.A.; Machumu, H.J.; DeSmet, E. Micro-credentials in higher education institutions: An exploratory study of its place in Tanzania. Int. J. Educ. Dev. Using Inf. Commun. Technol. 2019, 15, 233–244. (In English) [Google Scholar]

- Tinsley, B.; Cacicio, S.; Shah, Z.; Parker, D.; Younge, O.; Luna, C.L. Micro-Credentials for Social Mobility in Rural Postsecondary Communities: A Landscape Report. Digit. Promise 2022. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED622550.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- White, S. Developing credit based micro-credentials for the teaching profession: An Australian descriptive case study. Teach. Teach. 2021, 27, 696–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, R.; Grevatt, H.; Dworak, E.; Marsh, L.; Doty, S. Developing and evaluating an asynchronous online library microcredential: A case study. Ref. Serv. Rev. 2020, 48, 699–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddy, C.; Ponte, F. Preparing students for university studies and beyond: A micro-credential trial that delivers academic integrity awareness. J. Aust. Libr. Inf. Assoc. 2019, 68, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmat, N.H.C.; Bashir, M.A.A.; Razali, A.R.; Kasolang, S. Micro-Credentials in Higher Education Institutions: Challenges and Opportunities. Asian J. Univ. Educ. 2021, 17, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillon, G.; McNeill, B.; Scott, A.; Arrow, A.; Gath, M.; Macfarlane, A. A better start literacy approach: Effectiveness of Tier 1 and Tier 2 support within a response to teaching framework. Read. Writ. 2022, 36, 565–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillon, G.; McNeill, B.; Scott, A.; Denston, A.; Wilson, L.; Carson, K.; Macfarlane, A.H. A better start to literacy learning: Findings from a teacher-implemented intervention in children’s first year at school. Read. Writ. 2019, 32, 1989–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillon, G.; McNeill, B.; Scott, A.; Gath, M.; Macfarlane, A.; Taleni, T. Large scale implementation of effective early literacy instruction. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1354182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.; Gillon, G.; McNeill, B.; Kopach, A. The evolution of an innovative online task to monitor children’s oral narrative development. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 903124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillon, G.; Smith, J.P.; Maitland, R.; Macfarlane, S.; Macfarlane, A. The Better Start Literacy Approach: Using He Awa Whiria to inform design. In He Awa Whiria: Braiding the Knowledge Streams in Research, Policy and Practice; Macfarlane, A., Derby, M., Macfarlane, S., Eds.; Canterbury University Press: Canterbury, New Zealand, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garet, M.S.; Heppen, J.B.; Walters, K.; Parkinson, J.; Smith, T.M.; Song, M.; Borman, G.D. Focusing on Mathematical Knowledge: The Impact of Content-Intensive Teacher Professional Development; National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED569154.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Yoon, K.S.; Duncan, T.; Lee, S.W.-Y.; Scarloss, B.; Shapley, K. Reviewing the Evidence on How Teacher Professional Development Affects Student Achievement; Regional Educational Laboratory Southwest: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; Available online: http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Meissel, K.; Parr, J.M.; Timperley, H.S. Can professional development of teachers reduce disparity in student achievement? Teach. Teach. Educ. 2016, 58, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tooley, M.; Hood, J. Harnessing Micro-Credentials for Teacher Growth: A National Review of Early Best Practices; New America: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rienties, B.; Calo, F.; Corcoran, S.; Chandler, K.; FitzGerald, E.; Haslam, D.; Harris, C.A.; Perryman, L.-A.; Sargent, J.; Suttle, M.D.; et al. How and with whom do educators learn in an online professional development microcredential. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2023, 8, 100626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, M.S. My farewell address... Andragogy no panacea, no ideology. Train. Dev. J. 1980, 34, 48–50. [Google Scholar]

- McChesney, K.; Aldridge, J.M. What gets in the way? A new conceptual model for the trajectory from teacher professional development to impact. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2021, 47, 834–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. TALIS 2018 Results (Volume I); OECD: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bubb, S.; Earley, P.; Hempel-Jorgensen, A. Staff Development Outcomes Study; London Centre for Leadership in Learning: London, UK, 2008; Available online: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10002843/1/Bubb2008staffTDA.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Earley, P. ‘State of the Nation’: A discussion of some of the project’s key findings. Curric. J. 2010, 21, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.; Gu, Q. Variations in the conditions for teachers’ professional learning and development: Sustaining commitment and effectiveness over a career. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2007, 33, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpendale, J.; Berry, A.; Cooper, R.; Mitchell, I. Balancing fidelity with agency: Understanding the professional development of highly accomplished teachers. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A.; Chen, X. Online Education and Its Effective Practice: A Research Review. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res. 2016, 15, 157–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacCallum, K.; Brown, C. Developing a Micro-Credential for Learning Designers: A Delphi Study. ASCILITE Publ. 2022, e22198. Available online: https://publications.ascilite.org/index.php/APUB/article/view/198, (accessed on 12 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- Şahin, A.; Soylu, D.; Jafari, M. Professional Development Needs of Teachers in Rural Schools. Iran. J. Educ. Sociol. 2024, 7, 219–225. [Google Scholar]

- Hardesty, C.; Moody, E.J.; Kern, S.; Warren, W.; Hidecker, M.J.C.; Wagner, S.; Arora, S.; Root-Elledge, S. Enhancing Professional Development for Educators: Adapting Project ECHO From Health Care to Education. Rural. Spéc. Educ. Q. 2020, 40, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemay, D.J.; Bazelais, P.; Doleck, T. Transition to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2021, 4, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahasoan, A.N.; Ayuandiani, W.; Mukhram, M.; Rahmat, A. Effectiveness of Online Learning in Pandemic COVID-19. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Manag. 2020, 1, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedoyin, O.B.; Soykan, E. COVID-19 pandemic and online learning: The challenges and opportunities. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 31, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McChesney, K.; Cross, J. How school culture affects teachers’ classroom implementation of learning from professional development. Learn. Environ. Res. 2023, 26, 785–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drysdale, L.; Goode, H.; Gurr, D. An Australian model of successful school leadership: Moving from success to sustainability. J. Educ. Adm. 2009, 47, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Elliott, S.N.; Goldring, E.; Porter, A.C. Leadership for learning: A research-based model and taxonomy of behaviors1. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2007, 27, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, R.; Vulliamy, G.; Sarja, A.; Hämäläinen, S.; Poikonen, P. Professional learning communities and teacher well-being? A comparative analysis of primary schools in England and Finland. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2009, 35, 405–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cohort | Number Enrolled | Number Completed | Completion Rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literacy specialists | 1—January 2021 | 103 | 98 | 95% |

| 2—July 2021 | 117 | 84 | 86% | |

| 3—January 2022 | 118 | 105 | 96% | |

| 4—July 2022 | 79 | 65 | 91% | |

| 5—January 2023 | 179 | 160 | 98% | |

| 6—July 2023 | 101 | 96 | 95% | |

| 7—January 2024 | 112 | - | - | |

| Total | 809 | 512 | 94% (average) | |

| Teachers | 1—January 2021 | 341 | 278 | 87% |

| 2—July 2021 | 528 | 307 | 77% | |

| 3—January 2022 | 812 | 685 | 93% | |

| 4—July 2022 | 515 | 415 | 91% | |

| 5—January 2023 | 1125 | 991 | 96% | |

| 6—July 2023 | 516 | 502 | 97% | |

| 7—January 2024 | 825 | - | - | |

| Total | 4662 | 2676 | 91% (average) |

| Organizing Category | Code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Positive | Navigation/ organization | The organization of Learn was supportive of learning |

| Time commitment | The time commitment to familiarize with the site was worth it | |

| Resources | The resources were adequate and supplemented learning. | |

| Availability | Able to access resources when needed. | |

| Technical/user support | Support available if any user problems. | |

| Layout | The Learn website layout is user friendly. | |

| Content | Content enhances learning/support. | |

| Miscellaneous | Other positive comments not captured by main codes. | |

| Negative | Navigation/ organization | The organization of Learn hindered learning. |

| Time commitment | The time taken to access information is too slow. | |

| Resources | Further resources would have enhanced learning. | |

| Availability | Unable to access resources when needed. | |

| Technical/user support | Support not readily available if any user problems. | |

| Layout | The Learn website layout is not user friendly. | |

| Content | Content did not enhance learning/support. | |

| Course design | The course design did not fully support learning. | |

| Miscellaneous | Other negative comments not captured by main codes. |

| Organizing Category | Code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Positive | Presenters | The presenters were well organized, informative and engaging. |

| Accessibility | The sessions were easily available. | |

| Content | The information shared was useful and promoted learning and support. | |

| Format | The sessions were well organized. | |

| Timing | The timing of the sessions within the course structure was appropriate to learning needs. | |

| Design | The teaching sessions were well structured. | |

| Supportive learning | The teaching sessions were supportive of learning. | |

| Miscellaneous | Other positive comments not related to main codes. | |

| Negative | Accessibility | Sessions were not easily available. |

| Content | The information shared was not useful and did not promote learning and support. | |

| Format | The sessions were not well organized. | |

| Timing | The timing of the sessions within the course structure was not appropriate to learning needs. | |

| Design | The teaching sessions were not well structured. | |

| Supportive learning | The teaching sessions were not supportive of learning. | |

| Miscellaneous | Other negative comments not related to main codes. |

| Organizing Category | Code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Experiences | Delivery | The delivery of the course content, including videos, Zooms and online teaching content. |

| Structure | The flow and pacing of the information. | |

| Content | Information presented in the content, including demonstration videos and reading. | |

| Training | Overarching course and PLD. Included:Pedagogical strengthening: understanding the why’s and how’s of teaching literacy.Research based approach: understanding the research behind it, best practice and trusting it because of ongoing research.Student success: the training has led to visible student achievement. | |

| Resources | The material resources provided as part of the training, including lesson plans and other teaching resources. | |

| Accessibility | Being able to apply, use, find, understand and attend the various components of the micro-credential. | |

| Assessment | The literacy assessments for the students. | |

| Standardization | Streamlined data and concept. | |

| Support | Help from facilitators, educators and tech. | |

| Negative Experiences | Workload (course and teaching) | The overwhelming amount of things to do in a limited amount of time. This included workload directly related to the course (e.g., attending Zooms and completing assignments) and teaching workload (e.g., fitting the course teaching content into the daily classroom schedule). |

| Inadequacy | The lack of information, resources or data, or teachers’ feeling that it is not serving their students well. | |

| Inaccessibility | Being unable to apply, use, find, understand and attend the various components of the micro-credential. | |

| Lack of Support | Not being able to access help from facilitators, teaching team or wider school support, such as senior leadership. | |

| Organization | Issues with the way the course, information, resources or delivery was set up. | |

| Inconvenience | Having to put extra effort into one or more components of the course. | |

| Delivery | Problems with online delivery. | |

| Assessment administration | Problems with how long it took to administer assessments to children, understand and gather data, work with spreadsheets, assessments being unwieldy for children. | |

| Suggestions/ Improvements | Extra Resources | Additional resources to help people understand the teaching approach better. |

| Communicate expectations | Provide clear information about the setup of the teaching approach, the effort required to complete the micro-credential and the transparency about the workload. | |

| Notify changes | With the website continuously updating, create a mechanism for notifying teachers of any changes made. | |

| Resource availability | Provide resources beyond week 10 or a place where teachers can buy them since making them is time-consuming. | |

| Resource modification | Change some resources to better suit schools. | |

| Course modification | Increase the course length/modify course materials, content, delivery and structure. | |

| Simplify website | Learn and the assessment website are clunky with a lot of information badly organized. | |

| Practical approach | A more hands-on approach with teaching in classrooms involved in the early stages. |

| Model Fit | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-Statistic | p-Value | |

| Educator Type | 1.43 | 1 | 1.43 | 2.34 | 0.13 |

| Descriptive Statistics | |||||

| N | Mean | SD | 95% Lower CI | 95% Upper CI | |

| Literacy specialists | 85 | 1.61 | 0.73 | 1.46 | 1.77 |

| Teachers | 178 | 1.77 | 0.81 | 1.65 | 1.89 |

| Code | Positive | Negative |

|---|---|---|

| Navigation/Organization | 61.77% | 57.14% |

| Time commitment | 2.94% | 7.14% |

| Course design | 0% | 5.95% |

| Resources | 17.65% | 2.38% |

| Teacher support | 1.47% | 0% |

| Availability | 7.35% | 7.14% |

| Technical/user support | 1.47% | 8.33% |

| Content | 1.47% | 7.14% |

| Layout | 1.47% | 2.38% |

| Miscellaneous | 4.41% | 2.38% |

| Code | Positive | Negative |

|---|---|---|

| Presenters | 19.64% | 0.00% |

| Accessibility | 23.21% | 3.03% |

| Content | 19.64% | 26.67% |

| Format | 3.45% | 33.33% |

| Timing | 12.50% | 3.33% |

| Design | 3.57% | 16.67% |

| Supportive of learning | 16.07% | 3.33% |

| Miscellaneous | 1.72% | 13.33% |

| Organizing Category | Code | Benefits | Challenges | Overall Thoughts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Experiences | Delivery | 5.73% | - | 8.0% |

| Structure | 15.1% | - | 18.2% | |

| Content | 12.5% | - | 11.8% | |

| Training | 26.0% | - | 17.5% | |

| Resources | 15.8% | 12.5% | 15.8% | |

| Accessibility | 7.7% | 12.5% | 10.3% | |

| Standardization | 1.6% | 0.4% | ||

| Support | 8.8% | 62.5% | 9.9% | |

| Assessment | 3.2% | 12.5% | 2.9% | |

| Other | 2.8% | - | ||

| Negative Experiences | Workload | 20% | 36.7% | 12.4% |

| Inadequacy | 5.1% | 2.6% | ||

| Inaccessibility | 40.0% | 5.9% | 4.8% | |

| Lack of support | - | 5.9% | 2.2% | |

| Organization | - | 18.9% | 5.6% | |

| Inconvenience | 20.0% | 3.9% | 2.9% | |

| Delivery | - | 2.2% | 0.5% | |

| Assessment administration | - | 15.3% | 3.1% | |

| Other | - | 7.0% | 0.5% | |

| Improvements | Extra resources | - | - | 2.8% |

| Communicate expectations | - | - | 27.8% | |

| Notify changes | 14.3% | - | 11.1% | |

| Resource availability | 14.3% | - | 11.1% | |

| Resource modification | - | 23.1% | 8.3% | |

| Course modification | 57.1% | 76.9% | 19.4% | |

| Simplify website | - | - | 5.5% | |

| Practical approach | - | - | 5.5% | |

| Other | 14.3% | - | 5.5% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Scott, A.; Gath, M.E.; Gillon, G.; McNeill, B.; Ghosh, D. Facilitators of Success for Teacher Professional Development in Literacy Teaching Using a Micro-Credential Model of Delivery. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 578. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060578

Scott A, Gath ME, Gillon G, McNeill B, Ghosh D. Facilitators of Success for Teacher Professional Development in Literacy Teaching Using a Micro-Credential Model of Delivery. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(6):578. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060578

Chicago/Turabian StyleScott, Amy, Megan E. Gath, Gail Gillon, Brigid McNeill, and Dorian Ghosh. 2024. "Facilitators of Success for Teacher Professional Development in Literacy Teaching Using a Micro-Credential Model of Delivery" Education Sciences 14, no. 6: 578. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060578

APA StyleScott, A., Gath, M. E., Gillon, G., McNeill, B., & Ghosh, D. (2024). Facilitators of Success for Teacher Professional Development in Literacy Teaching Using a Micro-Credential Model of Delivery. Education Sciences, 14(6), 578. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060578