1. Introduction

This paper is an innovative attempt to quickly scan methodological approaches within the field of EdTech, drawing specifically on the articles contained within the Special Issue of Education Sciences on decolonising educational technology for which we served as editors (https://www.mdpi.com/journal/education/special_issues/2XT510Z1D6, accessed on 12 May 2024). A secondary goal is to carry out an exercise in horizon scanning for what the next steps might be, methodologically and in the fields of EdTech as well as research more generally with communities who could be described as outside the mainstream, especially as these steps pertain to decolonisation. We finish with an axiology of decolonising research based on the collated findings from all the papers we received.

Throughout this paper we will look to methodological insights that we hope will help develop research designs, principles, tools, and techniques that will better correspond to and align with people, communities, cultures, and societies who differ and diverge from the Global Northern mainstream context, and particularly those who live, operate, and learn in situations and contexts that can be defined as disadvantaged or developmental. Similarly to an earlier paper [1], we begin by briefly outlining what we mean by disadvantage and, first, decolonisation. (Even here, we, some of the current authors, fight the style guides that prefer American English spellings and auto-correct our mother tongue).

2. Decolonisation

All of the editors acknowledge that we live and work in Global Northern contexts, and are in many ways products of the Eurocentric mindset, but, as we state in the introduction to the Special Issue [2], we advocate for a more socially just and more educationally powerful use of EdTech, which is currently principally based on the uncritical and unthinking adoption of hegemonic and ubiquitous Western technologies that are themselves inherently based on Global Northern mindsets, approaches, beliefs, languages, and understandings (cf. [3]). We state in our introduction [2] that the integration into education of these technologies may have the unintended consequences of perpetuating colonial biases and reinforcing existing societal power imbalances (e.g., [4,5]), and that we—by which we mean the entire educational establishment—need to engage with this and aim to create change. We need to look to disentangle educational praxis and its neocolonial heritage: to decolonise it. This is by no means an easy task, but the conversation has started in research [6]; in methodology [7,8]; in Higher Education [9]; and in education generally [10]. We welcome this, and this paper looks to push this conversation further as it pertains to educational technology.

3. Problematising Discourse of Disadvantage

Not everyone who is outside a Global Northern context is disadvantaged, and the term is problematic both within and without this context [11]. We tend to avoid the term “marginalised” for the similar reason that it can easily be misconstrued and read as pejorative, implying impotence or incapacity; however, for the purposes of this paper, we are specifically discussing decolonising EdTech with the intention of empowering groups who face detriment, prejudice, or lack of opportunity for one or more of the following reasons:

- Security (e.g., those in contexts of crisis, natural disaster, emergency, conflict, and displacement, as well as the subsequent trauma);

- Capacity (e.g., disability, lack of access, poverty, lack of voice, and low status);

- Education (e.g., nonattendance, poor provision, dropout, narrow curricula, and poor teaching);

- Language (e.g., few speakers of mother tongue, nonliterate/preliterate societies, EdTech primarily available in English, non-national languages [local dialects, etc.], and suppression of mother tongues and indigenous cultures);

- Infrastructure (e.g., insecure buildings, camps, limited mains supply, poor roads, lack of bandwidth, and lack of digital devices);

- Access (e.g., isolation, distance, sparsity of habitation, poor roads, no school, lack of bandwidth, wealth, and lack of digital devices);

- Power (traditionally stigmatised groups, e.g., because of position within society, caste, class, homeless, rural, marginal, nomadic, gender-based, generational, wealth, sexual orientation, and religion).

Unfortunately, these communities are often faced with many of these barriers, rather than just one. We are not proposing “EdTech” as a panacea that can overcome these barriers. (Indeed, the idea of “EdTech” is itself problematic since it is usually refers, unchallenged, to those dedicated digital technologies sold into education systems and serving the institutional mission as well as values of those systems and overlooks the extent to which the wider population is using digital technologies, such as social media and other web 2.0 applications, for informal individual and community learning. Coloniality, specifically digital neocolonialism, is manifest in all these technologies and in the hardware, infrastructure, and systems upon which they run [12], in both the “North” as much as the “South”. Note: “EdTech” is presumed to be digital technology; traditionally, it could also refer to chalkboards, books, etc.). However, we believe that effective education can support and empower individuals and communities to make changes as well as offer better life chances.

4. Decolonising Research

However, each indigenous, disadvantaged, or otherwise marginalised community is found within their own unique social and cultural circumstances, which we have elsewhere described as being characterised by, for example, “environmental differences, historic differences, community/cultural/traditional differences, cultural practices, linguistics, and world views” [13]. We note that this clearly militates against the idea of adopting, transplanting, or operationalising pre-existing strategies from other contexts (such as the Global North), be these political, educational, technological, or research-oriented [1]. The circumstances and contexts of communities across the globe who are facing one or more of these highlighted barriers are highly diverse, and any interventions and research on and with these peoples, as well as the solutions provided, should be equally diverse [14], as should the technologies used to support these. They should also, as we will argue throughout, be developed in discussion with, and with the involvement and collaboration of, these communities.

To push this point about research further, as we noted in the introduction to this Special Issue, the research methods in use in low-income countries and disadvantaged regions are generally predigital and Global Northern (and, no doubt, gendered and ableist) and, as with the EdTech we discussed above, they often still reflect Western colonial thought and prejudice, and are now being enacted and supported through neocolonial, anglophone hegemonic digital technologies. These may be appropriate in some areas of disadvantage—for example, with the deaf and hard of hearing in Canada, or rural communities in Wales (two communities with whom some of the editors have worked); however, they are less appropriate, for example, for preliterate communities on the margins of societies in hard-to-access parts of the globe. Hence, we ask what might work for the hard-to-reach.

5. Decolonising Research Methodologies

We draw here on some of the most cited and influential texts in the field, rather than conducting our own systematic review or metanalysis. The word “decolonisation” itself has become increasingly used in educational research over the last few years. Barnes [15] notes that the field of decoloniality is somewhat of a mess of competing ideologies, understandings, and assumptions, and that focusing too closely and narrowly on decolonising research methodologies will be to the detriment of the wider decolonial agenda. Prior noted that “even the word research arouses feelings of suspicion and defensive attitudes. Indigenous people are generally cynical about the benefits of research and cautious toward what many perceive to be the colonial mentality or ‘positional superiority’ ingrained in the psyche of western researchers” [16] (p. 162). Keikelame and Swartz [17] argue that reflexivity and self-reflexivity on the part of “non-aboriginal” researchers (p. 6), for which we substitute any researcher outside the community being researched, “cannot be overemphasised” and that being aware of their participants’ actual responses, and not their own interpretation of these, will allow any researcher to “conduct appropriate research among marginalised and vulnerable populations” (p. 6).

Thambinathan and Kinsella [8] give a convincing overview of the field, and suggest four key approaches that researchers should adopt: “(1) exercising critical reflexivity, (2) enabling reciprocity and respect for self-determination, (3) embracing “Other(ed)” ways of knowing, and (4) embodying a transformative praxis” (online).

In terms of EdTech, Adam and Sarwar [5] raise the important point that we must not conflate this with Open Educational Resources (OERs), but also that this too has inherent and unspoken colonial thinking built-in from the start, and they too have begun to question its universality and relevance through similar lenses to those with which we investigated disadvantage: access, equity, language, skills, and global imbalances resulting from geopolitics. They also raise concerns that OERs and EdTech may have negative effects, including “using openness to effectively further exclusion (through using one central, universal system of knowledge—including language—that marginalises all others)” among others.

Traxler and Smith (2020), in their paper [1] on innovative research methodologies (expanded on subsequently in a series of workshops for e/mergeAfrica (e.g., https://bit.ly/4bsGoNA, accessed on 19 May 2024), discussed a number of methodological approaches that they claim are more appropriate for research in marginalised, disadvantaged, informal, or developmental contexts. We do not intend to rehash these discussions, but we note the potential usefulness of moving away from an over-reliance on what we then called “the usual suspects” of interviews, questionnaires, surveys, focus groups, and observations. Rather, for researchers keen to explore new and different “ways of knowing” away from traditional Global Northern epistemic praxis and to elicit participants’ own worldviews and understandings, rather than have them mediated through a Western perspective, we recommend instead investigating methods such as Personal Construct Theory using card sorts [18] or laddering [19], soft system methodologies [20], rich pictures [21,22], sandboxing [23], Write, Show, Draw, Tell [24], and photo elicitation or photovoice [25]. There is, however, the equally serious issue of appropriate research ethics and the dilemma that methods and ethics pose: culturally appropriate research methods could develop culturally appropriate research ethics, but culturally appropriate research methods need culturally appropriate research ethics in order to proceed.

6. Decolonising EdTech: Methodological Approaches from the Special Issue

Yang [26] writes very powerfully about supporting his participants (students) to use autoethnographic poetry to capture “what typical academic prose tends to leave out: rhythm, sound, imagery, as well as the intense emotions and voices of the participants, especially those from marginal backgrounds” (p. 2). Drawing on a range of literature, Yang goes on to say that “autoethnographies often foreground the experiences, emotions, and perspectives of marginalised groups such as female sociologists in a male-dominated academia, indigenous scholars in a West-dominated discipline, and multilingual professionals in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL)” (p. 2). There are clear parallels here with, e.g., sandboxing or rich pictures, where the participants tell their story in ways that are authentically theirs, unmediated by the questions of researchers which are, even with the best of intentions, imbued with their own perspectives of what they should be asking, based on their own beliefs, ethos, and worldviews. This “allows the marginalised to speak against the culturally dominant other with their own voices” [26] (p. 2). As well as opening epistemically diverse systems of knowledge production, a second level to this decolonial approach is that it can also negate the power dynamic between teacher and student, and allow for horizontal rather than vertical learning as well as teaching (cf. [27] Yang finds that technology can be a two-faced coin: neither inherently good nor evil, it can be used for either and gives examples of how the latter may work: specifically in not “marginalising individuals and groups only as data providers and consumers of knowledge” (but) the decolonizing ways, in contrast, are honouring, sharing, and collaborating (p. 13). He imagines two people, one on either side of epistemological injustice but “bonded by… technologies/As equals” (p. 12), and notes that decolonising EdTech can be as simplistic as using current technology to support the voices of the marginalised: “through this emergent translanguaging literature, we are no longer voiceless; we have raised our collective voice under a translanguaging banner to reconsider multilinguals as knowledge makers” (p. 14)).

Costa et al. [28] state presciently, if somewhat provocatively, that the decolonisation movement has focused on types and understandings of knowledge and of learning at the expense of the inter-relationships that drive teaching and learning. They note the obvious potential of using digital approaches as “digital cultures are a global phenomenon” (p. 10), but caution against an “emphasis on knowledge as a product than on knowing practices as processes” (p. 10).

Morgan [29] provides something of a stinging critique of MOOCs in the Global South. He shows that there are issues with low course completion and certification, the low value employers place on MOOC qualifications, poverty and poor infrastructure hindering course attendance and completion, and a lack of course content available in native languages, with over 80% of MOOCs only being available in English (pp. 6, 7). He also notes that “although MOOCs may create learning opportunities for people in the Global South, critics view them as a source that may ignore the importance of culture and local academic content” (p. 10). It is also the case that MOOCs tend to perpetuate a top-down and transmissive form of education. To overcome some of these difficulties, Morgan cites [30], who has declared that MOOCs need to be more supportive rather than often only allowing for autonomous learning and to be available in local languages. One suggestion we endorse, where possible, is the setting up of community partnerships to offer further support. This certainly seems more achievable than the somewhat wishcasting of some other authors for those offering MOOCs to ensure better infrastructure or to provide enrolees with digital hardware. Morgan ends with the hope that “providing MOOCs that encourage student participation and minimise the passive exchange of knowledge will likely lead to more democratic outcomes” (pp. 10–11).

Smith and Scott [31] describe a method that itself can be critiqued through a decolonial lens, in that although they were expressly seeking answers from their participants, who had all been partners on a joint project in Palestine, the questions were posed by the authors rather than eliciting data from the participants in a purer form; however, in rebuttal to this charge, it must be noted that there are two uncredited authors: local Palestinian academics whose names have been removed for their own safety. The questions were, therefore, created and supported by local actors, which [32] notes enables participants to produce accounts that are representative of and meaningful to the actors within the research and the setting, and to “use naturalistic data, critical discourse analysis and phenomenography, because (they are) ‘culturally literate’” (op. cit. p. 2) in the setting and community being researched. This “feel for the game and the hidden rules” [33] (p. 27) means the authors feel “empowered to offer a thick description [34] of lived realities, of the hermeneutics of everyday life” [32] (p. 2). We take from this the recommendation, similar to that of Keikelame and Swartz [17], that non-native researchers work where possible with academics from the local contexts.

Farrow et al. [35] take a similar stance. They note that Open Educational Resources “provide opportunities to diversify the curriculum and challenge the dominance of Eurocentric and Western knowledge” and “promote the democratisation of knowledge by removing barriers to access and participation in education” (p. 2) by allowing educators to adapt content for their own contexts, allowing for communities and individuals who have been “historically excluded or underrepresented in formal education systems to engage with educational resources (and) contribute their knowledge”. However, as with Morgan [29] in addition to Smith and Scott [31], they note the vital importance of mentoring and guidance, peer collaboration, and effective learning resources and tools, as well as insightful and supportive assessment and feedback. OERs have elsewhere been critiqued as instruments of digital neocolonialism [36], but Farrow et al. aim here to demonstrate how Supported Open Learning (SOL) can support researchers and communities to try to break the interlinked and “mutually reinforced” (p. 5) trifecta of the coloniality of power, of knowledge, and of being. In harmony with other papers in this Special Issue, most noticeably Smith and Scott, they note that where Western institutions are acting as the lead partners in international projects, there is a clear challenge in avoiding bringing Global Northern attitudes and beliefs, and that “there is a delicate balancing act to be struck between providing leadership in a particular domain and respecting the autonomy and self-determination of the collaboration partners” (p. 15).

Kohnke and Foung [37] do not add to the methodological discussion of working with disadvantaged and under-represented communities per se, but they give an excellent sketch of how to methodically interrogate data using the PRISMA [38] method. Their own research into the colonisation of data has led them to six key conclusions about ethical and decolonised practice in using data, including respecting its sovereignty, avoiding the manipulation of users, having a decolonialised approach to ethical clearance upstream, better as well as more equitable systems, and clear information for participants in how their data will be used.

Barnes et al. [39] note that EdTech can be seen as an arms race in which neo- and postcolonial Western companies compete to create resources that they can export into Global South contexts with little or no local, cultural, linguistic, societal, or community contextualisation, which Mazari et al. [40] show leads to responses that are “colonial at best”, and instead call for the development of socially just and decolonised EdTech using the principles for digital development (https://digitalprinciples.org/ accessed on 12 May 2024) developed by the Digital Impact Alliance (2017; 2024). Drawing on two key projects with refugees in Rwanda and Pakistan, Barnes et al. also show the importance of “designing ‘with’ rather than ‘for’ refugees as they navigate their educational journeys post-displacement” (p. 13) (this approach resonates strongly with Richard Heeks’ formulation of ICT4D2.0 [41]). They discuss focus group discussions (FDGs) as being well placed to support decolonial approaches as they allow participants’ views to emerge through interaction, so that “the participants’ rather than the researcher’s agenda can predominate” [42]. Following their discussion of their research findings, they offer these key factors for creating positive interactions through EdTech: (a) clear purpose of skills development for better life opportunities, (b) contextualised content, (c) language support, (d) illustrative visuals, (e) facilitated interactive elements, (f) expertise of presenters, (g) clear, easy to navigate delivery style, (h) self-paced options, and, finally, (i) being free of charge (p. 17), before offering a series of conclusions we urge all EdTech entrepreneurs to engage with.

Tompkins, Herman, and Ramage [43] report on an iterative survey and focus group research design investigating attitudes and perspectives of students on computing courses at a large open university in the UK. Their participants identified ten barriers to effective decolonisation of the curriculum, six faced by students and four by the institution. These are broadly in line with previous research identified in the article, but whilst there were worryingly ambivalent and even aggressively hostile attitudes to decolonisation within computing education in HE, there were some positive signs, such as students being “well aware of the complexities and challenges of such changes, and many are open to widening their understanding” (p. 15).

Kuhn, Warui, and Kimani [44] describe social research via the extended metaphor of a kitambaa, or woven tapestry of multiple threads, or knowledges (plural). They have approached their research through the lens of critical realism, utilising the human development capability approach and applying critical pedagogy to approach “futures literacy”. The theme that continually speaks through this paper is convivial, shared, reciprocal, and communal emancipatory action.

Similarly, Bhattacharya, Nandakumar, Dasgupta, and Murthy [45] describe a collaborative approach to EdTech involving multiple stakeholders, each applying the lens of “justice-as-process” through their varied perspectives to collectively influence the decision-making process in the usefulness or otherwise of EdTech solutions in India. It is reciprocity and social cohesion that are continually highlighted as strengths through all of the papers in the Special Issue.

7. Decolonising Research Methodologies: The Transformative Paradigm

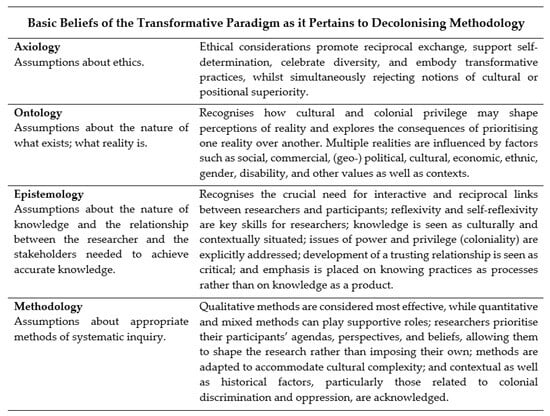

We have distilled the above into a version of Merten’s [46] Transformative Paradigm (Figure 1, below). This still draws heavily on her original, but we have updated it in light of the research in this Special Issue.

Figure 1.

Basic beliefs of the Transformative Paradigm as it pertains to decolonising methodology, drawing on Mertens (1998; 2005).

In summary, Figure 1 shows a clear need for researchers—especially those from the Global North—to consciously examine themselves and their assumptions for aspects of colonial thought and reject notions or positions of superiority, even when assuming leadership roles within the research, and to work in reciprocal partnership with all participants in their projects, drawing on local and contextual expertise to support all aspects of research (design, implementation, data collection, analysis, and dissemination). Dialogic research methods are seen as more effective, especially when power dynamics are identified and mitigated, allowing for the authentic voices of participants to shine through.

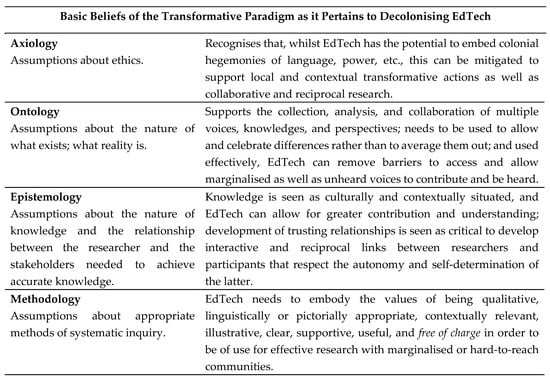

We have created a similar synopsis of the four aspects of Merten’s Transformative Paradigm for EdTech specifically (Figure 2), based on the extant literature in the field and drawing specifically on the papers produced for this Special Issue.

Figure 2.

Basic beliefs of the Transformative Paradigm as it pertains to decolonising EdTech, drawing on Mertens (1998; 2005).

8. Conclusions and Recommendations

These two figures together embody the essence of our Special Issue. They tie together the strands of multiple papers on EdTech and its uses for research, much as Kuhn, Warui, and Kimani [44] wove together a kitambaa from all the disparate sources in their research. There are clear cautions in these papers about the unthinking replication of colonial thought and practice by automatically selecting those methods and tools known to researchers without very careful thought about the target participants and their needs, contexts, and situations. It is all too easy to unconsciously promulgate colonial hegemonies of language and technological oppression through the automatic use of Western methods, questions, and even technologies.

There is also a wellspring of hope in this collection of papers, noting that where researchers collaborate reciprocally with participants and local actors in a culturally appropriate manner, accepting the expertise and input from stakeholders within the contextual situations, the research projects are more effective, enjoy greater support from participants, and have a greater chance of transformational success.

We finish by returning to Yang’s (2023) [26] vision of people situated on either side of epistemological injustice but “bonded by… technologies/As equals” (p. 12). EdTech, quote/unquote, has clear potential for misuse and abuse where it is exported with little or no local, cultural, linguistic, societal, or community contextualisation into contexts that have been described as the “epistemic underside” ([47,48])—i.e., those whose knowledge and perspectives have not impacted on a global stage; however, where culturally relevant technological support is used judiciously by multiple stakeholders, it can drive greater understanding and transformative practices, allowing researchers and participants to be reciprocally bonded through their use of technology, as equals, for more equitable and socially just outcomes.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Traxler, J.; Smith, M. Data for development: Shifting research methodologies for COVID-19. J. Learn. Dev. 2020, 7, 306–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koole, M.; Traxler, J.; Smith, M.; Adam, T.; Footring, S. Special Issue: Decolonising Educational Technology. Educ. Sci. 2024; in press. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/education/special_issues/2XT510Z1D6 (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Zavala, M. What do we mean by decolonizing research strategies? Lessons from decolonizing, Indigenous research projects in New Zealand and Latin America. Decolonization Indig. Educ. Soc. 2013, 2, 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Waghid, F. Towards Decolonisation Within University Education: On the Innovative Application of Educational Technology. In Education for Decoloniality and Decolonisation in Africa; Manthalu, C.H., Waghid, Y., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, T.; Sarwar, M.B. Decolonising Open Educational Resources (OER): Why the Focus on ‘Open’ and ‘Access’ Is Not Enough for the EdTech Revolution. 2022. Available online: https://opendeved.net/2022/04/08/ (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- Stokes, G. The questions we ask, the voices we use: Is a move towards more diverse message carriers and a rethinking of methodological approaches a means to decolonising research methods. In Proceedings of the RMC 2023: Research Methodology Conference, Decolonising Research Methodologies and Methods, London, UK, 16 June 2023; Available online: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10172138/ (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Smith, L.T. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, 2nd ed.; Zed Books Ltd.: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Thambinathan, V.; Kinsella, E.A. Decolonizing methodologies in qualitative research: Creating spaces for transformative Praxis. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2021, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adefila, A.; Teixeira, R.V.; Morini, L.; Garcia, M.L.T.; Delboni, T.M.Z.G.F.; Spolander, G.; Khalil-Babatunde, M. Higher education decolonisation: #Whose voices and their geographical locations? Glob. Soc. Educ. 2022, 20, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battiste, M. Decolonizing Education: Nourishing the Learning Spirit; Purich Publishing: Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kellaghan, T. Towards a Definition of Educational Disadvantage. Ir. J. Educ./Iris Eireannach Oideachais 2001, 32, 22. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30076741 (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Traxler, J. Decolonising Educational Technology, Futures of Education; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Traxler, J.; Smith, M.; Scott, H.; Hayes, S. Learning through the Crisis: Helping Decision-Makers around the World Use Digital Technology to Combat the Educational Challenges Produced by the Current COVID-19 Pandemic. EdTech Hub. 2020. Available online: https://docs.EdTechhub.org/lib/CD9IAPFX (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Park, S.; Freeman, J.; Middleton, C. Intersections between connectivity and digital inclusion in rural communities. Commun. Res. Pract. 2019, 5, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, B.R. Decolonising research methodologies: Opportunity and caution. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2018, 48, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, D. Decolonising research: A shift toward reconciliation. Nurs. Inq. 2007, 14, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keikelame, M.J.; Swartz, L. Decolonising research methodologies: Lessons from a qualitative research project, Cape Town, South Africa. Glob. Health Action 2018, 12, 1561175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, D.; Warfel, T. Card sorting: A definitive guide. Boxes Arrows 2004, 2, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Rugg, G.; McGeorge, P. The sorting techniques: A tutorial paper on card sorts, picture sorts and item sorts. Expert Syst. 2005, 22, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checkland, P.; Poulter, J. Soft systems methodology. In Systems Approaches to Managing Change: A Practical Guide; Hoverstad, P., Reynolds, M., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2010; pp. 191–242. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S.; Morse, S. How People Use rich pictures to help them think and act. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 2012, 26, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, T.; Pooley, R. Rich pictures: Collaborative communication through icons. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 2012, 26, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannay, D.; Lomax, H.; Fink, J. Scissors, sand and the cutting room floor: Employing visual and creative methods ethically with marginalised communities. In Proceedings of the British Sociological Association Annual Conference, Glasgow, UK, 15–17 April 2015; Available online: https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/69102/ (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Noonan, R.J.; Boddy, L.M.; Fairclough, S.J.; Knowles, Z.R. Write, draw, show, and tell: A child-centred dual methodology to explore perceptions of out-of-school physical activity. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Burris, M.A. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ. Behav. 1997, 24, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S. Decolonizing Technologies through Emergent Translanguaging Literature from the Margin: An English as a Foreign Language Writing Teacher’s Poetic Autoethnography. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, B. Vertical and horizontal discourse: An essay. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 1999, 20, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.; Bhatia, P.; Murphy, M.; Pereira, A.L. Digital Education Colonized by Design: Curriculum Reimagined. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, H. Improving Massive Open Online Courses to Reduce the Inequalities Created by Colonialism. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.R. Do MOOCs contribute to student equity and social inclusion? A systematic review 2014–2018. Comput. Educ. 2020, 145, 103693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Scott, H. Distance Education under Oppression: The Case of Palestinian Higher Education. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trowler, P. Researching Your Own Institution: Higher Education. British Educational Research Association On-Line Resource. 2011. Available online: https://www.bera.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Researching-your-own-institution-Higher-Education.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Bourdieu, P. Homo Academicus; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, C. The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973; Volume 5019. [Google Scholar]

- Farrow, R.; Coughlan, T.; Goshtasbpour, F.; Pitt, B. Supported Open Learning and Decoloniality: Critical Reflections on Three Case Studies. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, T. Digital neocolonialism and massive open online courses (MOOCs): Colonial pasts and neoliberal futures. Learn. Media Technol. 2019, 44, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohnke, L.; Foung, D. Deconstructing the Normalization of Data Colonialism in Educational Technology. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, K.; Emerusenge, A.P.; Rabi, A.; Ullah, N.; Mazari, H.; Moustafa, N.; Thakrar, J.; Zhao, A.; Koomar, S. Designing for Social Justice: A Decolonial Exploration of How to Develop EdTech for Refugees. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazari, H.; Baloch, I.; Thinley, S.; Kaye, T.; Perry, F. Learning Continuity in Response to Climate Emergencies: Supporting Learning Continuing Following the 2022 Pakistan Floods; EdTech Hub: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Available online: https://docs.EdTechhub.org/lib/IHTU7JRT (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Heeks, R. The ICT4D 2.0 Manifesto: Where Next for ICTs and International Development? Development Informatics Working Paper no. 42; SSRN: Rochester, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education, 8th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tompkins, Z.; Herman, C.; Ramage, M. Perspectives of Distance Learning Students on How to Transform Their Computing Curriculum: “Is There Anything to Be Decolonised?”. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, C.; Warui, M.; Kimani, D. Kitambaa: A Convivial Future-Oriented Framework for Kinangop’s Learning Hub. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, L.; Nandakumar, M.; Dasgupta, C.; Murthy, S. Shaping the Discourse around Quality EdTech in India: Including Contextualized and Evidence-Based Solutions in the Ecosystem. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, D.M. Transformative Research and Evaluation; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Grosfoguel, R. The Structure of Knowledge in Westernized Universities: Epistemic Racism/Sexism and the Four Genocides/Epistemicides of the Long 16th Century. Hum. Archit. J. Sociol. Self-Knowl. 2013, 11, 73–90. Available online: https://scholarworks.umb.edu/humanarchitecture/vol11/iss1/8/ (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Hlabangane, N. The underside of modern knowledge: An epistemic break from western science. In Decolonising the Human: Reflections from Africa on Difference and Oppression; Steyn, M., Mpofu, W., Eds.; Wits University Press: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2021. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).