1. Introduction

In the field of education, the influence of feedback on students’ motivation and engagement has emerged as a topic of significant importance and scrutiny [

1,

2,

3]. Among the diverse forms of feedback, positive feedback stands out as a potentially influential factor in fostering a conducive learning environment [

4,

5,

6].

While the concept of feedback extends across various domains such as management, medicine, and sports, it has garnered substantial attention within educational settings. Researchers in this field have dedicated considerable efforts over nearly a century to unravel the strategic utilization of feedback, aiming to enhance its efficacy for students. Their endeavors have aimed to guide students towards a developmental trajectory characterized by a growth-oriented mindset, heightened motivation, and increased engagement [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

Feedback represents a mechanism for regulating the learning process considered at the micro level of education, which requires the receiver of the messages transmitted by the sender to provide the sender with answers and information about the messages received [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Learning happens continuously, based on the effects of our decisions and actions. To achieve our goals, we constantly evaluate feedback received from those who have a pertinent opinion, update our knowledge, and adjust our behavior. Positive feedback holds a crucial role in education, akin to an accomplished conductor directing a harmonious display of individual strengths. Beyond mere acknowledgment of accomplishments, positive feedback is a deliberate and tactical form of praise that accentuates the specific abilities of each learner. This approach fosters a sense of accomplishment, builds confidence, and cultivates a favorable self-perception.

One of the key attributes of positive feedback is its capacity to reinforce desirable behaviors. By specifically acknowledging and applauding actions, initiatives, or contributions that align with desired learning outcomes, positive feedback functions as a stimulus for constructive learning value formation [

16,

17]. Encouraged by recognition, learners are motivated to build upon and replicate their successes.

The concept of a growth mindset, as proposed by [

18], is a central argument for the impact of positive feedback. When students receive positive feedback that emphasizes effort, perseverance, and improvement, they are more likely to adopt a growth mindset—the belief that intelligence and skills can be developed through engagement and hard work. Thus, positive feedback emerges as an effective tool in shaping students’ attitudes towards specific difficulties and instilling faith in the potential for continuous development [

19,

20,

21,

22]. In the “symphony” of education, positive feedback can be perceived as a melody that lends strength. It fortifies students’ confidence not only in their current achievements but also in their entire learning journey. By recognizing and highlighting strengths, both big and small, a positive feedback loop is established, in which learners feel empowered to tackle new challenges with a firm conviction in their ability to succeed.

By providing specific and meaningful positive feedback, teachers can reinforce targeted behaviors and skills in students, thereby promoting their motivation and self-esteem. Positive feedback not only influences motivation, but also impacts students’ self-concept and self-esteem [

23,

24,

25]. Self-concept is a multifaceted construct that develops through an association of experiences, interactions with others, and attributions of one’s own behavior. It is a dynamic construct that can change over time and plays a crucial role in human behavior, and is central to theories of social and motivational learning. The development of the self-concept is influenced by relevant people in a person’s entourage, such as parents, siblings, teachers and peers, who are frames of reference for establishing one’s self-evaluation.

The essence of the concept of self is rooted in the psychological dimension, which refers to the complex interplay of thoughts, beliefs, and emotions that shape an individual’s self-image. It is here that perceptions of a person’s abilities, values, and personal characteristics are formed through cognitive processes such as self-reflection and introspection. The internal dialogue that emerges from these processes is influenced by both conscious and subconscious elements and is the foundation on which the self-concept develops. The psychological dimension acts as a mirror, reflecting the dynamic interplay between aspirations, self-perceived limitations and the ongoing narrative that individuals construct in their minds. When students receive positive feedback, it contributes to shaping their self-perception in a positive way. They develop a positive self-image as capable students, which increases their self-esteem. Studies have shown that feedback that includes messages about efficacy and self-esteem can have a significant impact on student learning outcomes [

26,

27,

28]. Students who receive positive feedback are more likely to use appropriate strategies to improve their learning. In addition, positive feedback may also improve students’ self-efficacy beliefs. Self-efficacy beliefs refer to an individual’s belief in his or her own ability to succeed in specific tasks or situations.

Feedback is of major importance in the development of the instructional process, from a formative point of view, within and outside of instructional activities, which can be understood by stating that feedback creates relevant data about the learner, on the basis of which re-evaluations, assumptions, and goals are constructed, with the aim of improvement, in the context of performing instructional functions. Once the relevance of feedback is recognized, the subsequent challenge is to determine where to deliver or apply it, and subsequently to incorporate it into the everyday teaching and learning experience [

29,

30]. Over the decades, initiatives have been undertaken to define a variety of methods by which feedback can be delivered, and in the situational model developed by [

31], among the attributes associated with the instructor are “positive feedback functions” and “negative feedback functions” [

31].

In the first category, a teacher may exhibit the following behaviors [

32]:

Displaying stereotypical approval;

Validation through repetition of the student’s response;

Expressions of effort results;

Acceptance in a personal manner.

For the second approach, contradictory trends may be observed, including [

33]:

Displaying stereotypical disapproval;

Criticism through repetition in an ironic or threatening manner;

Reactions that show disregard;

Delayed feedback.

To provide positive feedback, a competent teacher incorporates the following elements into the act of teaching:

Extensive knowledge of the subject matter to be taught;

A set of skills, attitudes, and dispositions towards the learning process;

The capacity to design, create, and select methods that encourage active student participation in teaching activities.

Teachers can provide positive feedback through structured discussions with clearly defined objectives. These discussions, which are systematically organized with specific goals in mind, focus on recommendations and opinions. The teacher can interact with students based on the particulars of the tasks and their individual circumstances. It is crucial that these discussions are organized in a systematic manner to ensure that both the teacher and the students can make the most of their experience [

34].

Dialogue that centers on positive feedback encourages autonomy and independence in students, and protects them from the anxiety of failure by understanding that the purpose of communication is to regulate the conditions necessary for good functioning. When students continue to receive feedback during an activity, they can gradually gain experience, make necessary adjustments, and improve their results. It is important to note that the most effective feedback includes an explanation of what is correct and what is not correct in the student’s answers. Students may be asked to continue working on a task and to persevere until they reach their set goals, which can improve their performance [

35,

36,

37].

Feedback is valued by many teachers because it encourages students to acquire knowledge and increase their performance in learning activities; however, feedback techniques are complicated and sometimes fail to provide a meaningful outcome relative to the resources and time invested [

38,

39].

Feedback research and implementation are supported by a variety of theoretical approaches. In order to reduce gaps between actual and intended levels of performance, students need to process the feedback they receive, analyze it, and take corrective action. This is the focus of cognitive techniques [

40,

41]. Research [

41] captures social and cultural perspectives towards feedback. This ambivalent process, manifested as action and interaction between teacher and student, highlights the importance of cooperation and relevance conveyed through action within the social environments and cultural circumstances embedded in the principles of different disciplines. According to socio-constructivist studies on feedback, individual and shared perceptions are constructed through the interaction and conversation of participants, collective experiences or meaning theory and the co-construction of the self [

42].

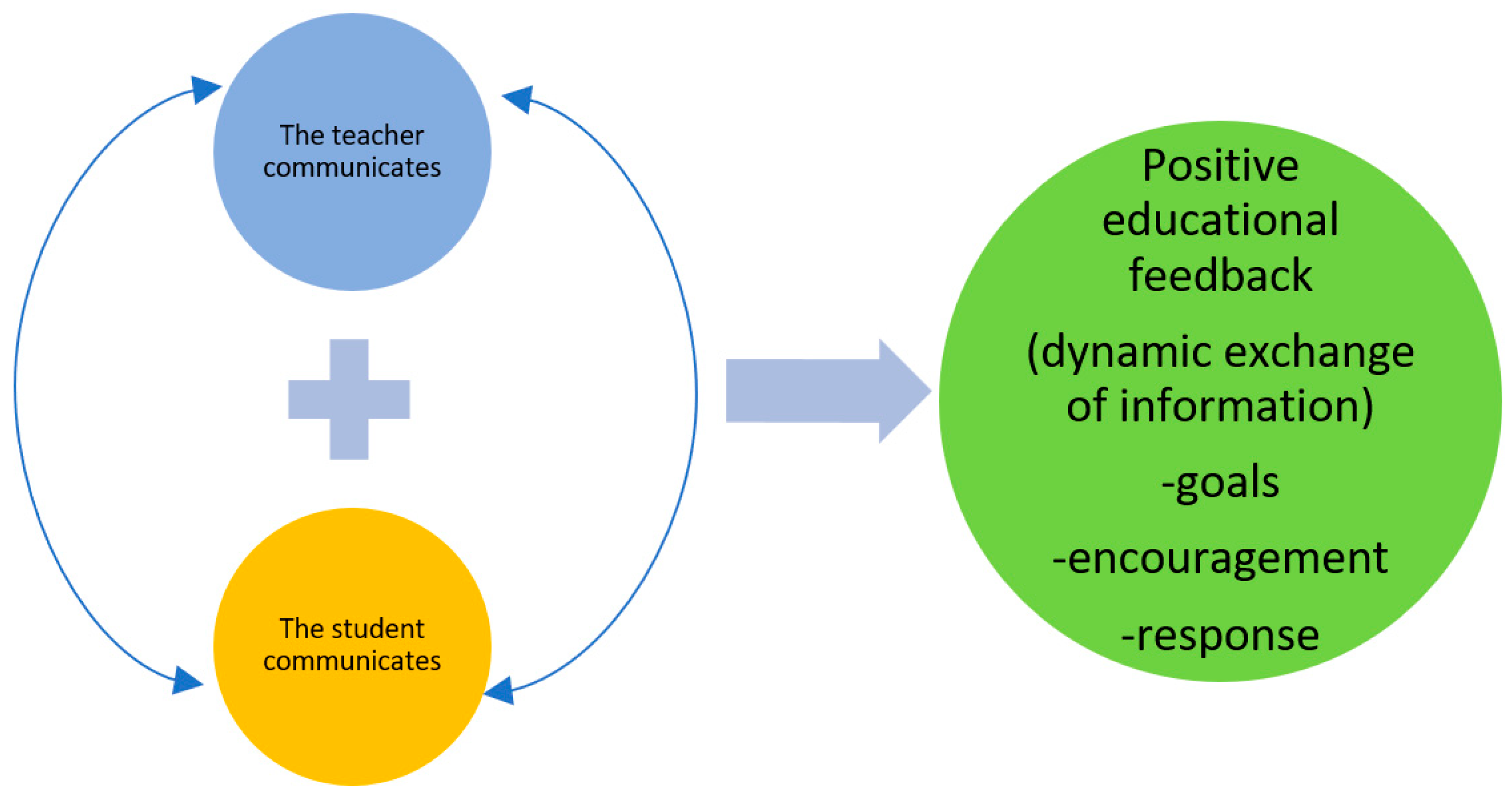

Feedback is essentially a discourse between educators and learners, characterized by its responsive and adaptive nature. Rather than a one-dimensional knowledge transfer, it is a fluid and sustained conversation that accommodates the evolving requirements of the student. This interactive quality necessitates a mutual exchange, whereby students are not merely receptors, but actively engaged in the feedback loop. Effective positive feedback (

Figure 1) is contingent upon unambiguous communication, congruence with learning goals, and nurturing a growth-oriented mentality [

43].

Education researchers and practitioners recognize the pivotal role teachers play in shaping the educational experience for students. This study aimed to explore the nuanced dimensions of feedback, with a particular emphasis on the positive variant, and its implications for the motivation and involvement of primary students. By examining teachers’ perceptions regarding the effects of positive feedback on student learning, we endeavored to unravel the process of feedback delivery and its potential to influence students’ academic journey.

2. Materials and Methods

Through this investigation, we aimed to provide valuable insights for educators, researchers, and policymakers seeking to enhance the quality of the learning experience. By unraveling the impact of positive feedback, this study endeavors to contribute to the ongoing dialogue on educational strategies that not only foster motivation but also cultivate an environment conducive to active student involvement and the nurturing of self-esteem.

As previously stated, feedback is a mechanism for regulating the learning process. It can refer to the action by which educators (teachers) obtain information about the effects of their pedagogical approaches and to the action by which learners obtain information about the effects of their learning efforts. Positive feedback is a type of feedback accompanied by reinforcement of the positive aspects of the learners’ work, in order to develop a constructive relationship between teacher and learner that will enable the setting of desirable objectives to be achieved [

11,

12].

Teachers consistently support and assess student learning. Feedback provided by teachers has been associated with enhanced student responses, increased engagement, and heightened participation.

The research strategy and design were developed to investigate the following research questions:

Is there a statistically significant correlation between positive feedback in educational activities and students’ motivation?

To what extent do teachers utilize positive feedback, and does the frequency of its application hold any significance in relation to student engagement and motivation according to teachers’ perceptions?

The objective of the present study was to investigate the role of teachers’ perception of positive feedback regarding their overall engagement of the students with feedback. Another objective of this paper was to investigate if the students are more motivated in the learning process when positive feedback is provided.

An educational undesired behavior can be improved if the way of giving feedback is well-known, if the consequences of applying this regulation mechanism are understood and if a constructive and meaningful communication is expected. In this manner, we intended to determine what are the attitudes and beliefs of teachers with regard to professional competencies, training, and professional development that enable effective teaching and learning. Also, we intended to investigate teachers’ practices with regard to giving feedback and positive feedback, and how often teachers provide positive feedback and the way teachers perceive students’ attitudes towards feedback.

The strategy for conducting the research consisted of one stage, based around the abovementioned research questions. During this phase, we conducted a quantitative analysis to investigate the teachers’ perceptions regarding the using of positive feedback during the educational learning process. As a research method, we opted for a questionnaire survey distributed online among pre-university teachers.

In our methodology, we utilized a suite of AI-assisted tools to enhance the quality and precision of our manuscript. DeepL and English Assister were employed for translation and grammatical correction, ensuring accurate translations and eliminating grammatical errors, alongside ChatGPT that was instrumental in stylistic correction and ensuring sentence coherence. Grammarly was utilized to identify and rectify incorrect usage of English, enhancing coherence and clarity. Additionally, dedicated software analyzed word frequency and generated visual word maps, facilitating the presentation of semantic connections.

2.1. Participants

There was a total of N = 455 teachers who took part in the research. The recruitment process utilized for this study involved a convenience sampling approach, specifically targeting pre-university teachers. Convenience sampling is a non-probability sampling method that selects participants based on their accessibility and willingness to participate. In this case, teachers were conveniently chosen due to their accessibility for the study.

The recruitment primarily took place online, where potential participants were invited to take part in the research through an online questionnaire. Convenience sampling was chosen for its practicality and efficiency, allowing for a quick and accessible means of gathering responses from teachers who were available and willing to contribute to the study [

44]. Participation was voluntary and consensual.

Out of the total sample of 455 participating teachers, 43.7% (199 respondents) were primary school teachers, while 56.3% were secondary and high school teachers.

Demographic information is revealed in

Table 1.

2.2. Instruments

In this study, we employed a self-developed online questionnaire to gather data pertinent to our research objectives. The questionnaire was developed by our team of researchers to ensure alignment with the specific parameters and goals of our investigation. Each item in the questionnaire was designed to capture key variables and insights essential to our study’s focus. The development of the questionnaire followed rigorous guidelines to uphold validity and reliability in data collection. Throughout the analysis, reference will be made to the questionnaire items, providing transparency regarding the instruments used in this research.

The questionnaire was structured in two sections: demographic items and items related to the feedback topic. For the first section of the questionnaire, we designed and analyzed 11 nominal variables to build a comprehensive picture of the statistical data received from respondents as we revealed in

Table 2, detailed below. The second section of the questionnaire consisted of closed-ended questions designed to measure two variables: utilization of positive feedback (the independent ordinal variable) and motivation of the students to actively participate (the dependent ordinal variable)—indicating whether or not the students were more engaged.

The answers to the questions were given using the five-step Likert scale (1—strongly disagree, 5—strongly agree). Google forms were used to collect the applicants’ responses to the questionnaire, which were submitted online.

To measure the internal consistency of the questionnaire we utilized the statistic Cronbach’s Alpha, which calculated the pairwise correlations between items in our survey. The value for Cronbach’s Alpha, α, is 0.869. We obtained a value falling in the range 0.8 ≤ α < 0.9, thus fulfilling the criteria of reliability as good (

Table 2).

The statistical processing of the research data was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0 software (Armonk, NY, USA: IBM Corp.).

3. Results

The following table shows the weights of the responses regarding the fact that most of the teachers at the institution had a common view on aspects of the teaching–learning process according to the gender of the respondents. In order to test the relationship between respondents’ gender and the responses regarding the fact that most of the teachers at the institution had a common view on aspects related to the teaching–learning process, we used the Chi-square test, for the calculation of which we started from the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis H0. There is no statistically significant association between the two variables.

Hypothesis H1. There is a statistically significant association between the two variables.

Since p = 0.858, hypothesis H0 is accepted. Bivariate Chi-square (χ2) test indicated no significant association between the two variables (χ2 = 1.323; df = 4, p = 0.858).

We observed that, regardless of gender, teachers’ responses were similar (

Table 3).

While the percentage of individuals aged 45 and above who expressed agreement or strong agreement that the majority of teachers at the institution shared a unified perspective on teaching–learning matters surpassed the corresponding percentage among those under 45 who agreed, the outcomes of the correlation analysis revealed no statistically significant differences (χ

2 = 26.879; df = 32;

p = 0.723) in the perceptions of whether most teachers at the institution shared a common view on aspects of the teaching–learning process based on the age of the questionnaire respondents (

Table 4).

Regardless of the level of education at which they taught, the teachers participating in the study had similar opinions, not significantly different, regarding the fact that most of the teachers at the institution had a common view on issues related to the teaching–learning process.

We observed that as teaching seniority increased, the share of those who agreed and strongly agreed that most teachers at the institution had a shared view on issues related to the teaching–learning process also increased.

However, the result of the statistical analysis (χ2 = 23.980; df = 24; p = 0.463) shows us that the opinions on the fact that most of the teachers at the institution had a common view on aspects related to the teaching–learning process did not differ statistically significantly according to seniority.

Regardless of biological gender, respondents were equally likely to agree with the statement “In the teaching–learning process I consistently give feedback to my students”, and this was not statistically significantly different. The result of the association analysis shows that the opinions on the statement “In the teaching–learning process I consistently give feedback to my students” did not differ significantly (χ2 = 46.407; df = 32; p = 0.058) according to the age of the questionnaire respondents.

We see that as teaching seniority increased, the proportion of those who strongly agreed that they consistently provide feedback to their students in the teaching–learning process also increase.

However, the result of the statistical analysis (χ2 = 28.460; df = 24; p = 0.241) shows us that the opinions on whether they consistently provide feedback to their students in the teaching–learning process did not differ statistically significantly according to seniority.

The overwhelming majority of teachers surveyed (94.7%) agreed and strongly agreed with the statement “I consider feedback to be a tool that can motivate and increase engagement in my activities”. Only 4.2% had a neutral opinion and only 1.1% disagreed with the statement.

A percentage of 84.7% of the survey participants agreed and strongly agreed that they provide feedback to students even in situations not related to their teaching activities “I give feedback to students even in situations not related to my teaching activities”. An additional 11.6% had a neutral opinion and 3.7% disagreed with this statement.

The results of the Chi-square test confirm the presence of a significant association between the gender of the respondent teacher and the opinion on the statement “I give feedback to students even in situations not related to my teaching activities” (χ2 = 13.569; df = 4; p = 0.009).

Women provided significantly more feedback to students in non-teaching situations than men.

In order to test the association between the level of education at which they teach and the study participants’ responses to the statement “I give feedback to students even in situations that are not related to my teaching activities” we used the Chi-square test. Since p = 0.022, there was a significant association between the level of education and the responses of study participants to the statement “I give feedback to students even in situations not related to my teaching activities” (χ2 = 11.484; df = 4; p = 0.022).

A total of 87.9% of primary teachers agreed and strongly agreed with the statement “I give feedback to students even in situations that are not related to my teaching activities”, 10.1% had a neutral opinion, and 2% disagreed with this statement.

Of those teaching at other levels, 82.1% agreed and strongly agreed with the statement “I give feedback to students even in situations that are not related to my teaching activities”. A total of 12.9% had a neutral opinion and 5.1% disagreed with this statement.

We thus found that teachers teaching at primary level provide feedback to students in non-teaching situations to a greater extent than teachers teaching at other levels. Cramer’s V coefficient (Cramer’s V = 0.159) indicates a low intensity relationship between the two variables (

Table 5).

Approximately 73.4% of the respondents strongly concurred with the assertion “I have noticed that when I construct feedback in a positive way, my students are more receptive”. Additionally, 18.9% expressed agreement, 6.4% held a neutral standpoint, and 1.4% disagreed with the statement. The association analysis revealed no statistically significant differences (χ2 = 47.946; df = 32; p = 0.055) in opinions concerning the impact of positive feedback construction on student responsiveness based on the age of the questionnaire respondents.

Regarding the statement “Positive feedback increases student engagement”, 69% of the respondents strongly agreed, while 22% expressed agreement. Meanwhile, 7.5% held a neutral stance, and only 1.5% disagreed. The Chi-square test results indicated a significant association between the age of the responding teachers and their opinions on the impact of positive feedback on student engagement (χ2 = 47.041; df = 32; p = 0.042).

Furthermore, among teachers under 40, there was a higher percentage expressing disagreement or neutrality toward the statement “Positive feedback increases student engagement” compared to their counterparts over the age of 40 (

Table 6).

Regardless of the level of education at which they teach, the teachers participating in the study had similar opinions, not significantly different, regarding the statement “Positive feedback increases student engagement”(

Table 7).

The statistical analysis results (χ2 = 33.346; df = 24; p = 0.063) indicate that there were no statistically significant differences in opinions regarding whether positive feedback increases student engagement based on seniority.

Regarding the frequency of providing positive feedback, a variety of responses were recorded. A notable portion of respondents, comprising 23.4%, indicated that they provide positive feedback as often as necessary. Conversely, only 1.5% reported providing positive feedback every hour, while 7.5% stated that they offer it on a daily basis. The majority of respondents, accounting for 53%, mentioned providing positive feedback once a week. Meanwhile, 13.6% reported providing positive feedback somewhat less frequently, with 6.8% indicating a bi-monthly frequency and another 6.8% mentioning a monthly interval.

To assess the association between the level of education taught and participants’ responses to the statement “We are interested in your opinion on providing constant positive feedback”, the Chi-square test was employed. Given the significance level of p < 0.001, a substantial association was identified between the level of education taught and participants’ opinions on constant positive feedback (χ2 = 30.266; df = 6; p < 0.001).

Upon closer examination, a higher proportion of primary school teachers tended to provide frequent positive feedback compared to educators at other levels of education. In contrast, teachers at different levels reported a higher percentage of providing positive feedback only on a bi-monthly or monthly basis. The calculated Cramer’s V coefficient (Cramer’s V = 0.258) indicates a low-intensity relationship between these two variables.

For item number 13, we were interested in capturing the frequency that teachers apply when providing feedback. Their responses were then analyzed and coded using the online software

https://monkeylearn.com/, accessed on 4 December 2023. We mapped the words that were most frequently mentioned by respondents (

Figure 2 below presented). A percentage of 53.0% was registered by choosing the option “once a week”. Other words that were registered are “once a month or monthly, once a week, daily, whenever it is needed, constant, when the situation calls for it, during every activity, depending on, several times a week”, indicating strong correlations among respondents’ questionnaire replies, the frequency of providing feedback to students, and active students engagement.

4. Discussion

The results of this study align with and contribute to the existing body of literature on teachers’ perceptions and practices within the teaching–learning process. Additionally, insights from recently published papers reinforce and extend the implications of our findings [

45,

46,

47].

Our study’s observation of consistent responses across genders echoes findings from the work of [

48,

49], where a unified perspective among male and female educators was noted. The absence of gender-based disparities in perceiving a common view on teaching–learning aspects aligns with the broader discourse in the literature, emphasizing the collaborative nature of effective teaching practices [

49].

Contrary to our expectation that age might influence perceptions, our results align with recent studies such as [

50], which found no substantial age-related differences in teachers’ views on collaborative teaching approaches. The growing consensus suggests that the commitment to shared perspectives transcends age, reflecting a collective commitment to effective pedagogy [

51].

The overwhelming agreement on the motivational role of feedback resonates with the extensive literature emphasizing its positive impact on student engagement [

52]. Our findings are in harmony with the work of [

52,

53,

54], reinforcing the notion that teachers universally recognize feedback as a potent tool for enhancing student motivation and engagement.

The lack of significant differences in opinions based on teaching seniority aligns with recent research by [

52], indicating that while there might be an observable trend towards increased agreement with experience, it does not necessarily translate into statistical significance. The identified association between primary school teachers and more frequent positive feedback echoes [

53,

54], suggesting that specific teaching contexts may shape feedback practices.

Our study shares limitations with similar research in relying on self-reported data and being context specific. Insights from highly cited works, such as [

55], underscore the need for future studies to adopt diverse methodologies and explore cross-cultural variations in teachers’ perceptions and practices.

The shared perspectives identified in this study and supported by recent literature emphasize the importance of targeted professional development programs. Integrating feedback practices and fostering a collaborative teaching environment should be prioritized in teacher training initiatives [

56].

Our study’s findings, in conjunction with seminal works like [

56], contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the broader educational landscape. Shared perspectives among teachers have implications for curriculum development, institutional policies, and the ongoing evolution of teaching methodologies.

In conclusion, this study, in conjunction with recent influential works, enhances our understanding of teachers’ shared perspectives and practices. The identified patterns underscore the need for a nuanced approach to professional development and highlight the integral role of feedback in shaping effective teaching–learning environments. Future research endeavors should build upon these foundations, exploring dynamic aspects of collaborative teaching practices across diverse educational settings.

5. Conclusions

This study accentuates the pivotal role of providing students with pertinent positive feedback as a powerful mechanism for enhancing motivation and engagement in educational endeavors. The exploration of diverse feedback procedures and their effectiveness is critical for the successful implementation of feedback strategies. Accurate comprehension of the impact of various feedback approaches can be achieved by meticulously documenting students’ responses and behaviors.

Upon conducting a quantitative analysis of teacher responses, a unanimous agreement emerged regarding the beneficial influence of positive feedback on student motivation and engagement. Nevertheless, caution is advised in attributing a significant impact on students’ academic awareness solely to positive feedback. This prompts further research inquiries, particularly delving into the nuanced role of positive feedback in shaping students’ educational trajectories [

57,

58].

Continuous learning, guided by teachers’ knowledge, understanding, and positive feedback, stands as a fundamental pillar for student development. The perpetual review of feedback, aligning with both current goals and past experiences, informs decisions and actions. Positive feedback, widely acknowledged by teachers, enhances students’ learning abilities and classroom performance.

Observations from this study suggest that positive feedback acts as a catalyst, amplifying productivity, motivation, and fostering a positive emotional environment. Its impact extends beyond individuals, influencing the cohesion and optimal functioning of both individuals and teams. Properly harnessed, positive feedback acts as a motivational coach, nurturing engagement among team members. However, the timing and manner of feedback delivery are crucial, as missteps can disrupt the delicate balance, affecting motivation and self-esteem.

Teachers, cognizant of the profound impact of their actions, wield a pivotal role in selecting feedback methods that facilitate accurate self-analysis and foster social analysis within teams. Creating moments of reflection before passing judgments on students’ work is imperative, ensuring that constructive and beneficial feedback aligns with the overarching goal of fostering motivation, engagement, and continuous improvement.

While this study sheds light on the positive effects of feedback, it is essential to acknowledge its limitations.

The reliance on quantitative analysis may overlook nuanced qualitative aspects. While our study utilized a quantitative methodology to address the research objectives, it is important to acknowledge the potential limitations inherent in this approach. The exclusive focus on quantitative data collection may have restricted the depth of insights obtained, omitting nuanced perspectives that qualitative methods could have provided. Future research endeavors could benefit from incorporating qualitative techniques to offer a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomena under investigation. Thus, future research could delve deeper into the qualitative dimensions of feedback, exploring students’ subjective experiences and perceptions. Additionally, the study’s generalizability is confined to the context in which it was conducted, and variations across different educational settings warrant consideration. Future investigations could employ diverse samples and settings to enhance the external validity of the findings. Furthermore, exploring the long-term effects of positive feedback on students’ academic trajectories would contribute valuable insights into sustained motivation and engagement.

Also, the study did not capture the perspective of students regarding feedback. Future research endeavors should consider incorporating student feedback to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the feedback dynamic. Additionally, the study did not include a comparative analysis across different cultural contexts. While the findings shed light on perceptions within the studied population, further research is needed to determine the generalizability of these findings across diverse cultural settings. Lastly, convenience sampling was utilized in this study, which may limit the representativeness of the findings. While convenience sampling allowed for focused insights into the particular group studied, caution should be exercised when generalizing the results to broader populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C., M.B., A.R., D.R. and C.C.; methodology, A.C., M.B., A.R., D.R. and C.C.; software, M.M., L.T.-C., Z.T., D.-G.T., D.M. and E.-L.M.; validation, M.M., L.T.-C., Z.T., D.-G.T., D.M. and E.-L.M.; formal analysis, R.R.-T., I.T., C.B., M.-G.N., I.D., C.C.C. and C.E.R.; investigation, A.C., M.B., A.R., D.R. and C.C.; resources, R.R.-T., I.T., C.B., M.-G.N., I.D., C.C.C. and C.E.R.; data curation, R.R.-T., I.T., C.B., M.-G.N., I.D., C.C.C. and C.E.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C., M.B., A.R., D.R. and C.C.; writing—review and editing, M.M., L.T.-C., Z.T., D.-G.T., D.M. and E.-L.M.; visualization, R.R.-T., I.T., C.B., M.-G.N., I.D., C.C.C. and C.E.R.; supervision, A.C., M.B. and A.R.; project administration, A.C. and M.B.; funding acquisition, A.C., M.B. and A.R. All authors have contributed equally to this research. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Center of Research Development and Innovation in Psychology of Aurel Vlaicu University of Arad (protocol code 48/10.11.2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request by the first author and the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

In our methodology, we utilized a suite of AI-assisted tools to enhance the quality and precision of our manuscript. DeepL and English Assister were employed for translation and grammatical correction, ensuring accurate translations and eliminating grammatical errors, alongside with ChatGPT that was instrumental in stylistic correction and ensuring sentence coherence. Grammarly was utilized to identify and rectify incorrect usage of English, enhancing coherence and clarity. Additionally, dedicated software analyzed word frequency and generated visual word maps, facilitating the presentation of semantic connections.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mangels, J.A.; Butterfield, B.; Lamb, J.; Good, C.; Dweck, C.S. Why do beliefs about intelligence influence learning success? A social cognitive neuroscience model. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2006, 1, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agricola, B.T.; Prins, F.J.; Sluijsmans, D.M. Impact of feedback request forms and verbal feedback on higher education students’ feedback perception, self-efficacy, and motivation. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 2020, 27, 6–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenka, A.C.; Linnenbrink-Garcia, L.; Moshontz, H.; Atkinson, K.M.; Sanchez, C.E.; Cooper, H. A meta-analysis on the impact of grades and comments on academic motivation and achievement: A case for written feedback. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 41, 922–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderman, M.K. Motivation for Achievement: Possibilities for Teaching and Learning; Routledge: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Alles, M.; Seidel, T.; Gröschner, A. Establishing a positive learning atmosphere and conversation culture in the context of a video-based teacher learning community. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2019, 45, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evnitskaya, N. Does a positive atmosphere matter? Insights and pedagogical implications for peer interaction in CLIL classrooms. Classr.-Based Conversat. Anal. Res. Theor. Appl. Perspect. Pedagog. 2021, 169–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelman, L. The influence of formal, substantive and contextual task properties on the relative effectiveness of different forms of feedback in multiple-cue probability learning tasks. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1981, 27, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluger, A.N.; DeNisi, A. Feedback interventions: Toward the understanding of a double-edged sword. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1998, 7, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipnevich, A.A.; Berg, D.; Smith, J.K. Toward a model of student response to feedback. In Human Factors and Social Conditions in Assessment; Brown, G.T.L., Harris, L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 169–185. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Gong, S.; Xu, S.; Hu, X. Elaborated feedback and learning: Examining cognitive and motivational influences. Comput. Educ. 2019, 136, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewski, B.; Zierer, K.; Hattie, J. The power of feedback revisited: A meta-analysis of educational feedback research. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocoș, M.-D.; Răduț-Taciu, R.; Stan, C. Dicționar de Pedagogie; Editura Presa Universitară Clujeană: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.; To, J. Proactive receiver roles in peer feedback dialogue: Facili-tating receivers’ self-regulation and co-regulating providers’ learning. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2022, 47, 1200–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedrakyan, G.; Malmberg, J.; Verbert, K.; Järvelä, S.; Kirschner, P.A. Linking learning behavior analytics and learning science concepts: Designing a learn-ing analytics dashboard for feedback to support learning regulation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 107, 105512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szumowska, E.; Szwed, P.; Wójcik, N.; Kruglanski, A.W. The interplay of positivity and self-verification strivings: Feedback preference under increased desire for self-enhancement. Learn. Instr. 2023, 83, 101715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stump, G.; Husman, J.; Chung, W.T.; Done, A. Student beliefs about intelligence: Relationship to learning. In Proceedings of the 2009 39th IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference, San Antonio, TX, USA, 18–21 October 2009; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Watling, C.J.; Ginsburg, S. Assessment, feedback and the alchemy of learning. Med. Educ. 2019, 53, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dweck, C.S.; Master, A. Self-theories motivate self-regulated learning. In Motivation and Self-Regulated Learning; Routledge: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012; pp. 31–51. [Google Scholar]

- Arens, A.K.; Jansen, M.; Preckel, F.; Schmidt, I.; Brunner, M. The structure of academic self-concept: A methodological review and empirical illustration of central models. Rev. Educ. Res. 2021, 91, 34–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffs, C.; Nelson, N.; Grant, K.A.; Nowell, L.; Paris, B.; Viceer, N. Feedback for teaching development: Moving from a fixed to growth mindset. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2023, 49, 842–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutumisu, M. The association between feedback-seeking and performance is moderated by growth mindset in a digital assessment game. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 93, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Kuusisto, E.; Nokelainen, P.; Tirri, K. Peer feedback reflects the mindset and academic motivation of learners. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, J.J.; Davis, T.H.; Hughes, B.L. A fluid self-concept: How the brain maintains coherence and positivity across an interconnected self-concept while incorporating social feedback. J. Neurosci. 2023, 43, 4110–4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPartlan, P.; Umarji, O.; Eccles, J.S. Selective importance in self-enhancement: Patterns of feedback adolescents use to improve math self-concept. J. Early Adolesc. 2021, 41, 253–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, J.P. 22 The Social Construction of Self-Esteem. In The Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020; p. 309. [Google Scholar]

- Alavi, S.M.; Kaivanpanah, S. Feedback expectancy and EFL learners’ achievement in English. Porta Linguarum 2009, 11, 99–114. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10481/31841 (accessed on 4 December 2023).

- Akoul, M.; Lotfi, S.; Radid, M. Effects of academic results on the perception of competence and self-esteem in students’ training. Glob. J. Guid. Couns. Sch. Curr. Perspect. 2020, 10, 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- Fathi, S. A constructive tool for enhancing learners’ self-esteem: Peer-scaffolded assessment. J. Engl. Lang. Res. 2020, 1, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Xu, Y. The development of student feedback literacy: The influences of teacher feedback on peer feedback. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 680–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carless, D. Longitudinal perspectives on students’ experiences of feedback: A need for teacher–student partnerships. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2020, 39, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Landsheere, G. Le Pilotage des Systèmes D’éducation; De Boek Université: Bruxelles, Belgium, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, C.J.; Patall, E.A.; Vasquez, A.C.; Stautberg, S. A meta-analysis of negative feedback on intrinsic motivation. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 31, 121–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azkarai, A.; Oliver, R. Negative feedback on task repetition: ESL vs. EFL child settings. Lang. Learn. J. 2019, 47, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisianita, S.; Mandasari, B. The use of small-group discussion to improve students’ speaking skill. J. Engl. Lang. Teach. Learn. 2022, 3, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzano, R.J. Marzano Levels of School Effectiveness; Marzano Research Laboratory: Centennial, CO, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Redeș, A.; Rad, D.; Roman, A.; Bocoș, M.; Chiș, O.; Langa, C.; Baciu, C. The Effect of the Organizational Climate on the Integrative–Qualitative Intentional Behavior in Romanian Preschool Education—A Top-Down Perspective. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocoș, M.; Mara, D.; Roman, A. Mentoring and metacognition—Interferences and interdependencies. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2024, 8, 2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carless, D.; Boud, D. The development of student feedback literacy: Enabling uptake of feedback. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 1315–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cădariu, I.E.; Rad, D. Predictors of Romanian Psychology Students’ Intention to Successfully Complete Their Courses—A Process-Based Psychology Theory Approach. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurlings, M.; Vermeulen, M.; Bastiaens, T.; Stijnen, S. Understanding feedback: A learning theory perspective. Educ. Res. Rev. 2013, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esterhazy, R.; Damşa, C. Unpacking the feedback process: An analysis of undergraduate students’ interactional meaning-making of feedback comments. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allal, L. Involving primary school students in the co-construction of formative assessment in support of writing. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 2021, 28, 584–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, C.M.; McLaughlin, A.C. Individual differences in the benefits of feedback for learning. Hum. Factors 2012, 54, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedgwick, P. Convenience sampling. BMJ 2013, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdas, F. Pre-Service Teachers’ Perceptions with Regard to Teaching-Learning Processes. J. Educ. Learn. 2018, 7, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Weher, M. The effect of a training course based on constructivism on student teachers’ perceptions of the teaching/learning process. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2004, 32, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.; Kozhevnikova, M. Styles of practice: How learning is affected by students’ and teachers’ perceptions and beliefs, conceptions and approaches to learning. Res. Pap. Educ. 2011, 26, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano-Sanchez, D.; Gomez-Marmol, A.; Valero-Valenzuela, A. Student and teacher perceptions of teaching personal and social responsibility implementation, academic performance and gender differences in secondary education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.; Janssen, J.; Wubbels, T. Collaborative learning practices: Teacher and student perceived obstacles to effective student collaboration. Camb. J. Educ. 2018, 48, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gegenfurtner, A.; Vauras, M. Age-related differences in the relation between motivation to learn and transfer of training in adult continuing education. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2012, 37, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, T.; Gore, J.; Ladwig, J. Teachers’ fundamental beliefs, commitment to reform and the quality of pedagogy. In Proceedings of the Australian Association for Research in Education Annual Conference, Deakin, Australia, 26–30 November 2006; pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, K.A. Seniority and experience of college teachers as related to evaluations they receive from students. Res. High. Educ. 1983, 18, 3–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtagh, L. The motivational paradox of feedback: Teacher and student perceptions. Curric. J. 2014, 25, 516–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, J.; Froehlich, D.E. Proactive feedback-seeking, teaching performance, and flourishing amongst teachers in an international primary school. In Agency at Work: An Agentic Perspective on Professional Learning and Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 425–444. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Q. Variations in beliefs and practices: Teaching English in cross-cultural contexts. Lang. Intercult. Commun. 2010, 10, 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawn, C.D.; Fox, J.A. Understanding the work and perceptions of teaching focused faculty in a changing academic landscape. Res. High. Educ. 2018, 59, 591–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, K.L.; Sax, L.J.; Wofford, A.M.; Sundar, S. The tech trajectory: Examining the role of college environments in shaping students’ interest in computing careers. Res. High. Educ. 2022, 63, 871–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.T.; Degol, J. Staying engaged: Knowledge and research needs in student engagement. Child Dev. Perspect. 2014, 8, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).