How Do Primary and Early Secondary School Students Report Dealing with Positive and Negative Achievement Emotions in Class? A Mixed-Methods Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

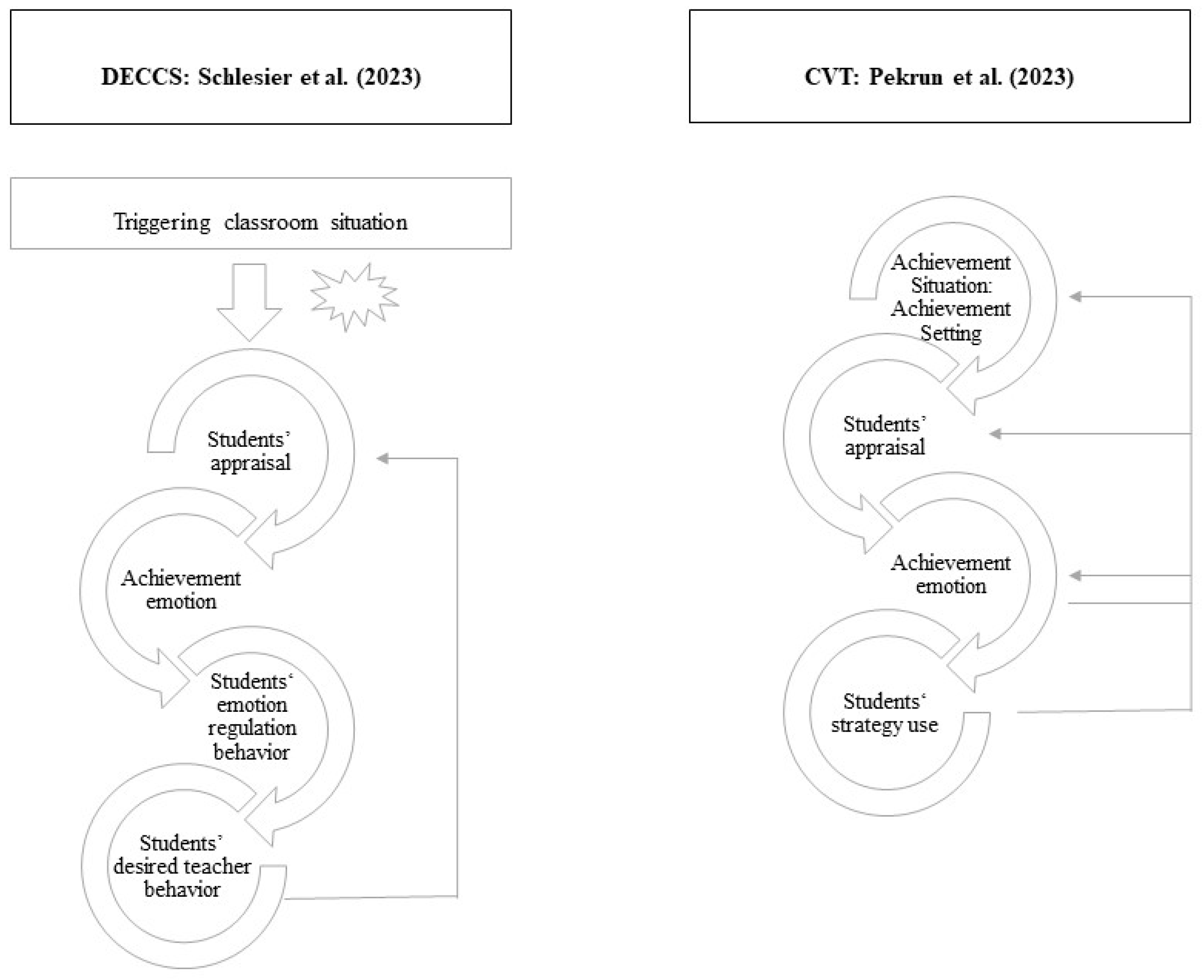

1.1. Students’ Achievement Emotions

1.2. Student’s Dealing with Emotions in Class

1.3. New Approaches to the Child’s Perspective on Their Own Emotions and Interactions

2. Aims and Hypotheses

- −

- To investigate how primary school students perceive and describe their interactions in achievement-emotion classroom situations regarding joy and pride (RQ1).

- −

- To explore the role of peer interactions in positive achievement-emotion classroom situations (RQ2).

- −

- To explore how primary and early secondary students deal with emotionally challenging classroom situations, targeting the interplay of students’ situation-specific appraisals, students’ negative achievement emotions, students’ emotion regulation behaviour, and their desired forms of teacher support (RQ3), considering grade-level and gender-specific differences as covariates in how students deal with emotionally challenging classroom situations.

3. Study 1

3.1. Methods

3.1.1. Participants and Procedures

3.1.2. Data Collection: Children’s Drawings and Interviews

| “Draw a situation from your lessons in which you had joy in learning on this school day or week.” “Draw a situation from your lessons in which you felt proud on this school day or week.” |

3.1.3. Data Analysis Procedures

3.2. Results

3.2.1. RQ1: Interactions in Achievement-Emotion Situations (Students’ Drawings and Interviews)

3.2.2. RQ2: The Role of Peer Interactions in Achievement-Emotion Situations (Children’s Drawings and Interviews)

4. Study 2

4.1. Methods

4.1.1. Sample and Procedures

4.1.2. Measures

4.1.3. Data Analysis Procedures

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2.2. SEM

5. General Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Discussion and Practical Implications

5.2. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Emotion Variable | M | SD | rit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Emotions | 2.49 | 0.88 | |

| Anxiety | 2.58 | 1.43 | 0.72 *** |

| Disappointment | 2.56 | 1.33 | 0.69 *** |

| Anger | 2.83 | 1.38 | 0.69 *** |

| Frustration | 2.54 | 1.35 | 0.72 *** |

| Shame | 1.83 | 1.16 | 0.67 *** |

| Learning Emotions | 2.14 | 0.89 | |

| Anxiety | 1.63 | 1.10 | 0.72 *** |

| Disappointment | 2.30 | 1.31 | 0.76 *** |

| Anger | 2.51 | 1.34 | 0.71 *** |

| Frustration | 2.10 | 1.31 | 0.75 *** |

| Shame | 2.05 | 1.27 | 0.72 *** |

References

- Chernyshenko, O.S.; Kankaraš, M.; Drasgow, F. Social and Emotional Skills for Student Success and Well-Being: Conceptual Framework for the OECD Study on Social and Emotional Skills. OECD Educ. Work. Pap. 2018, 173, 1–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B.W.; Kuncel, N.R.; Shiner, R.; Caspi, A.; Goldberg, L.R. The Power of Personality: The Comparative Validity of Personality Traits, Socioeconomic Status, and Cognitive Ability for Predicting Important Life Outcomes. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 2, 313–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krammer, M.; Tritremmel, G.; Auferbauer, M.; Paleczek, L. Durch Die Coronapandemie Belastet?“ Der Einfluss von Durch COVID-19 Induzierter Angst Auf Die Sozial-Emotionale Entwicklung 12- Bis 13-Jähriger in Österreich [Does the COVID-19 Pandemic Take Its Toll? The Influence of COVID-19 Anxiety on the Social-Emotional Development of 12- to 13-Year-Olds in Austria]. Z. Für Bild. 2022, 12, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nett, U.; Ertl, S.; Bross, T. Emotionales Erleben von Schüler*innen in Jahrgangsstufe 4 Unter Dem Einfluss Der COVID-19-Pandemie Im Schuljahr 2019/2020 [Students’ Emotional Experiences in Grade 4 during the COVID-19 Pandemic in the School Year 2019/2020]. Z. Für Grund. 2022, 15, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hußner, I.; Lazarides, R.; Westphal, A. COVID-19-Bedingte Online-vs. Präsenzlehre: Differentielle Entwicklungsverläufe von Beanspruchung Und Selbstwirksamkeit in Der Lehrkräftebildung? [Face-to-Face vs. Online Teaching in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Differential Development of Burnout and Self-Efficacy in Teacher Training?]. Z. Für Erzieh. 2022, 25, 1243–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westphal, A.; Kalinowski, E.; Hoferichter, C.J.; Vock, M. K−12 Teachers’ Stress and Burnout during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol 2022, 13, 920326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, P.; Atzmüller, C.; Su, D. Designing Valid and Reliable Vignette Experiments for Survey Research: A Case Study on the Fair Gender Income Gap. J. Methods Meas Soc. Sci. 2016, 7, 52–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesier, J.; Raufelder, D.; Moschner, B. Construction and Initial Validation of the DECCS Questionnaire to Assess How Students Deal with Emotionally Challenging Classroom Situations (Grades 4–7). J. Early Adolesc. 2023, 44, 141–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markkanen, P.; Välimäki, M.; Anttila, M.; Kuuskorpi, M. A Reflective Cycle: Understanding Challenging Situations in a School Setting. Educ. Res. 2020, 62, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrusnikova, I.; Dillon, S.R. Challenging Situations When Teaching Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders in General Physical Education. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2011, 28, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järvenoja, H.; Järvelä, S. Emotion Control in Collaborative Learning Situations: Do Students Regulate Emotions Evoked by Social Challenges? Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 79, 463–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Järvenoja, H.; Volet, S.; Järvelä, S. Regulation of Emotions in Socially Challenging Learning Situations: An Instrument to Measure the Adaptive and Social Nature of the Regulation Process. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 33, 31–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivuniemi, M.; Järvenoja, H.; Järvelä, S. Teacher Education Students’ Strategic Activities in Challenging Collaborative Learning Situations. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 2018, 19, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acee, T.W.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.-I.; Chu, H.-N.R.; Kim, M.; Cho, Y.; Wicker, F.W. Academic Boredom in Under- and over-Challenging Situations. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 35, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurki, K.; Järvelä, S.; Mykkänen, A.; Määttä, E. Investigating Children’s Emotion Regulation in Socio-Emotionally Challenging Classroom Situations. Early Child Dev. Care 2015, 185, 1238–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindqvist, H. Student Teachers’ and Beginning Teachers’ Coping with Emotionally Challenging Situations; Linköping University Electronic Press: Linköping, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- van Driel, S.; Crasborn, F.; Wolff, C.E.; Brand-Gruwel, S.; Jarodzka, H. Exploring Preservice, Beginning and Experienced Teachers’ Noticing of Classroom Management Situations from an Actor’s Perspective. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 106, 103435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesier, J. Lern- Und Leistungsemotionen, Emotionsregulation Und Lehrkraft-Schulkind-Interaktion: Ein Integratives Modell In Achievement Emotions, Emotion Regulation and Teacher-Student Interaction: An Integrated Model, 1st ed.; Kinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pekrun, R. The Control-Value Theory of Achievement Emotions: Assumptions, Corollaries, and Implications for Educational Research and Practice. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 18, 315–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. A Social-Cognitive, Control-Value Theory of Achievement Emotions. Adv. Psychol. 2000, 131, 143–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R.; Stephens, E. Achievement Emotions: A Control-Value Approach. Soc. Personal. Compass 2010, 4, 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R.; Frenzel, A.C.; Goetz, T.; Perry, R.P. The Control-Value Theory of Achievement Emotions. An Integrative Approach to Emotions in Education. In Emotion in Education; Schutz, P.A., Pekrun, R., Eds.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 13–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R.; Elliot, A.J.; Maier, M.A. Achievement Goals and Achievement Emotions: Testing a Model of Their Joint Relations with Academic Performance. J. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 101, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R.; Lichtenfeld, S.; Marsh, H.W.; Murayama, K.; Goetz, T. Achievement Emotions and Academic Performance: Longitudinal Models of Reciprocal Effects. Child Dev. 2017, 88, 1653–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarides, R.; Buchholz, J. Student-Perceived Teaching Quality: How Is It Related to Different Achievement Emotions in Mathematics Classrooms? Learn. Instr. 2019, 61, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohbeck, A.; Nitkowski, D.; Petermann, F. A Control-Value Theory Approach: Relationships between Academic Self-Concept, Interest, and Test Anxiety in Elementary School Children. Child Youth Care Forum 2016, 45, 887–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohbeck, A.; Grube, D.; Moschner, B. Academic Self-Concept and Causal Attributions for Success and Failure amongst Elementary School Children. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2017, 25, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenfeld, S.; Pekrun, R.; Marsh, H.W.; Nett, U.E.; Reiss, K. Achievement Emotions and Elementary School Children’s Academic Performance: Longitudinal Models of Developmental Ordering. J. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 115, 552–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mega, C.; Ronconi, L.; De Beni, R. What Makes a Good Student? How Emotions, Self-Regulated Learning, and Motivation Contribute to Academic Achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 106, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villavicencio, F.T.; Bernardo, A.B.I. Positive Academic Emotions Moderate the Relationship between Self-Regulation and Academic Achievement. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 83, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetz, T.; Frenzel, A.C.; Pekrun, R.; Hall, N.C. The Domain Specificity of Academic Emotional Experiences. J. Exp. Educ. 2006, 75, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raccanello, D.; Brondino, M.; De Bernardi, B. Achievement Emotions in Elementary, Middle, and High School: How Do Students Feel about Specific Contexts in Terms of Settings and Subject-Domains? Scand. J. Psychol. 2013, 54, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipp, S.-H. Adulthood: Developmental Tasks and Critical Life Events. In International Encyclopedia of the social and BEHAVIORAL Sciences; Smelser, N.J., Baltes, P.B., Eds.; Elsevier Science: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 153–156. [Google Scholar]

- Gentry, M.; Gable, R.K.; Rizza, M.G. Students’ Perceptions of Classroom Activities: Are There Grade-Level and Gender Differences? J. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 94, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieg, S.; Grassinger, R.; Dresel, M. Teacher Humor: Longitudinal Effects on Students’ Emotions. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2019, 34, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vierhaus, M.; Lohaus, A.; Wild, E. The Development of Achievement Emotions and Coping/Emotion Regulation from Primary to Secondary School. Learn. Instr. 2016, 42, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.; Schlesier, J. The Development of Students’ Achievement Emotions after Transition to Secondary School: A Multilevel Growth Curve Modelling Approach. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2021, 37, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M.; Neumann, M.; Tetzner, J.; Böse, S.; Knoppick, H.; Maaz, K.; Baumert, J.; Lehmann, R. Is Early Ability Grouping Good for High-Achieving Students’ Psychosocial Development? Effects of the Transition into Academically Selective Schools. J. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 106, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, D.; Sá, M.J. The Impact of the Transition to HE: Emotions, Feelings and Sensations. Eur. J. Educ. 2014, 49, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buff, A. Enjoyment of Learning and Its Personal Antecedents: Testing the Change–Change Assumption of the Control-Value Theory of Achievement Emotions. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2014, 31, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagenauer, G.; Hascher, T. Learning Enjoyment in Early Adolescence. Educ. Res. Eval. 2010, 16, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenfeld, S.; Pekrun, R.; Stupnisky, R.H.; Reiss, K.; Murayama, K. Measuring Students’ Emotions in the Early Years: The Achievement Emotions Questionnaire-Elementary School (AEQ-ES). Learn. Individ. Differ. 2012, 22, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, T.M.; Aldao, A. Gender Differences in Emotion Expression in Children: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychol. Bull 2013, 139, 735–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.A. Emotion Regulation: A Theme in Search of Definition. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child. Dev. 1994, 59, 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Fabes, R.A.; Shepard, S.A.; Murphy, B.C.; Guthrie, I.K.; Jones, S.; Friedman, J.; Poulin, R.; Maszk, P. Contemporaneous and Longitudinal Prediction of Children’s Social Functioning from Regulation and Emotionality. Child. Dev. 1997, 68, 642–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation: Current Status and Future Prospects. Psychol. Inq. 2015, 26, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesier, J.; Raufelder, D. Sozio-Emotionale Schulerfahrungen von Schüler:Innen–Theoretische Grundlagen, Methodische Herausforderungen Und Empirische Befunde. In Students’ Socio-Emotional School Experiences—Theoretical Foundations, Methodological Challenges and Empirical Insights; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R.; Marsh, H.W.; Elliot, A.J.; Stockinger, K.; Perry, R.P.; Vogl, E.; Goetz, T.; van Tilburg, W.A.P.; Lüdtke, O.; Vispoel, W.P. A Three-Dimensional Taxonomy of Achievement Emotions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 124, 145–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirvonen, R.; Poikkeus, A.M.; Pakarinen, E.; Lerkkanen, M.K.; Nurmi, J.E. Identifying Finnish Children’s Impulsivity Trajectories from Kindergarten to Grade 4: Associations with Academic and Socioemotional Development. Early Educ. Dev. 2015, 26, 615–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, E.G.; Wanless, S.B.; Rimm-Kaufman, S.E.; Cameron, C.E.; Peugh, J.L. The Contribution of Teachers’ Emotional Support to Children’s Social Behaviors and Self-Regulatory Skills in the First Grade. Sch. Psych. Rev. 2012, 42, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floress, M.T.; Jenkins, L.N.; Reinke, W.M.; McKown, L. General Education Teachers’ Natural Rates of Praise: A Preliminary Investigation. Behav. Disord 2018, 43, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, K.R.; Caldarella, P.; Larsen, R.A.A.; Charlton, C.T.; Wills, H.P.; Kamps, D.M.; Wehby, J.H. Teacher Praise and Reprimands: The Differential Response of Students at Risk of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 2019, 21, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurmi, J.-E. Students’ Characteristics and Teacher–Child Relationships in Instruction: A Meta-Analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 2012, 7, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partin, T.C.M.; Robertson, R.E.; Maggin, D.M.; Oliver, R.M.; Wehby, J.H. Using Teacher Praise and Opportunities to Respond to Promote Appropriate Student Behavior. Prev. Sch. Fail. 2009, 54, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwell, W.C.; Tiberio, J. Teacher Praise: What Students Want. J. Instr. Psychol. 1994, 32, 322. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.-Y.; Hughes, J.N.; Kwok, O.-M. Teacher–Student Relationship Quality Type in Elementary Grades: Effects on Trajectories for Achievement and Engagement. J. Sch. Psychol. 2010, 48, 357–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielak, J.; Mystkowska-Wiertelak, A. Investigating Language Learners’ Emotion-Regulation Strategies with the Help of the Vignette Methodology. System 2020, 90, 102208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudri, A.I.; Pervaiz, A.; Ali, R.A. A Descriptive Analysis of Emotion Regulation in the ESL Classroom of University Students: A Vignette Study. Int. J. Linguist. Cult. 2023, 4, 83–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulou, M. The Role of Vignettes in the Research of Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties. Emot. Behav. Difficulties 2001, 6, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosiek, J.; Beghetto, R.A. Emotional Scaffolding: The Emotional and Imaginative Dimensions of Teaching and Learning. In Advances in Teacher Emotion Research; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farokhi, M.; Hashemi, M. The Analysis of Children’s Drawings: Social, Emotional, Physical, and Psychological Aspects. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 30, 2219–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Meel, J.M. Representing Emotions in Literature and Paintings: A Comparative Analysis. Poetics 1995, 23, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driessnack, M. Children’s Drawings as Facilitators of Communication: A Meta-Analysis. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2005, 20, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brechet, C. Children’s Gender Stereotypes Through Drawings of Emotional Faces: Do Boys Draw Angrier Faces than Girls? Sex Roles 2013, 68, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkitt, E.; Sheppard, L. Children’s Colour Use to Portray Themselves and Others with Happy, Sad and Mixed Emotion. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 34, 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkitt, E.; Watling, D. The Impact of Audience Age and Familiarity on Children’s Drawings of Themselves in Contrasting Affective States. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2013, 37, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, T. What Can Year-5 Children’s Drawings Tell Us about Their Primary School Experiences? Pastor. Care Educ. 2015, 33, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romera, E.M.; Rodríguez-Barbero, S.; Ortega-Ruiz, R. Children’s Perceptions of Bullying among Peers through the Use of Graphic Representation/Percepciones Infantiles Sobre El Maltrato Entre Iguales a Través de La Representación Gráfica. Cult. Y Educ. Cult. Educ. 2015, 27, 158–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R.; Marsh, H.W.; Suessenbach, F.; Frenzel, A.C.; Goetz, T. School Grades and Students’ Emotions: Longitudinal Models of within-Person Reciprocal Effects. Learn. Instr. 2023, 83, 101626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raccanello, D.; Brondino, M.; Crescentini, A.; Castelli, L.; Calvo, S. A Brief Measure for School-Related Achievement Emotions: The Achievement Emotions Adjective List (AEAL) for Secondary Students. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2022, 19, 458–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesier, J.; Roden, I.; Moschner, B. Emotion Regulation in Primary School Children: A Systematic Review. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 100, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Padilla, A.M. Emotions and Creativity as Predictors of Resilience among L3 Learners in the Chinese Educational Context. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee Rad, H.; Jafarpour, A. Effects of Well-Being, Grit, Emotion Regulation, and Resilience Interventions on L2 Learners’ Writing Skills. Read. Writ. Q. 2023, 39, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Diao, H.; Jin, F.; Pu, Y.; Wang, H. The Effect of Peer Education Based on Adolescent Health Education on the Resilience of Children and Adolescents: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burić, I. The Role of Social Factors in Shaping Students’ Test Emotions: A Mediation Analysis of Cognitive Appraisals. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2015, 18, 785–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Tinti, C.; Levine, L.J.; Testa, S. Appraisals, Emotions and Emotion Regulation: An Integrative Approach. Motiv. Emot. 2010, 34, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, M.; Stright, A.D. Adolescents’ Emotion Regulation Strategies, Self-Concept, and Internalizing Problems. J. Early Adolesc. 2012, 32, 876–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parise, M.; Canzi, E.; Olivari, M.G.; Ferrari, L. Self-Concept Clarity and Psychological Adjustment in Adolescence: The Mediating Role of Emotion Regulation. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2019, 138, 363–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 3rd ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA; London, UK; New Delhi, India; Singapore, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. In Qualitative Forschung. Ein Handbuch; Flick, U., von Kardorff, E., Steinke, I., Eds.; Rowohlt: Reinbek bei Hamburg, Germany, 2015; pp. 468–475. [Google Scholar]

- Helfferich, C. Die Qualität Qualitativer Daten. Manual Für Die Durchführung Qualitativer Interviews; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuß, S.; Karbach, U. Grundlagen Der Transkription. Eine Praktische Einführung. In Basics of Transcription. A Practical Introduction; Budrich Verlag Opladen: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, G.C. Mistakes and How to Avoid Mistakes in Using Intercoder Reliability Indices. Methodology 2015, 11, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Cui, Y.; Chiu, M.M. The Relationship between Teacher Support and Students’ Academic Emotions: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2018, 8, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus. Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables. Users’ Guide; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 7th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- West, S.G.; Finch, J.F.; Curran, P.J. Structural Equation Models with Non Normal Variables: Problems and Remedies. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues and Applications; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ximénez, C.; Garcia, A.G. Comparación de Los Métodos de Estimación de Máxima Verosimilitud y Mínimos Cuadrados No Ponderados En El Análisis Factorial Confirmatorio Me- Diante Simulación Monte Carlo [Comparison of Maximum Likelihood and Unweighted Least Squares Estimation Methods in Confirmatory Factor Analysis by Monte Carlo Simulation]. Psicothema 2005, 17, 528–535. [Google Scholar]

- Ximénez, C. A Monte Carlo Study of Recovery of Weak Factor Loadings in Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Struct. Equ. Modeling 2006, 13, 587–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, X. Structural Equation Modeling: Applications Using Mplus; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, D.P. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asparouhov, T. Sampling Weights in Latent Variable Modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. 2005, 12, 411–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Main Category | Category | Sub-Category | Structure | Codes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triggers | Learning environment | Process-related | Learning activity with teacher |

|

| Usage media |

| |||

| Creative activity |

| |||

| Class discussion |

| |||

| Games |

| |||

| Objects |

| |||

| Goal-orientated | Public recognition in class |

| ||

| Learning activity |

| |||

| Creative activity |

| |||

| Games |

| |||

| Performance-related situation (performance approach) | Performance-associated | Allocation of marks (getting a test back) |

| |

| Presentation |

| |||

| Victory in class representative election |

|

| Main Category | Category | Sub-Category | Structure | Codes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relevant factors | Concentration capacity | General lack of concentration |

| |

| Social factors | Peer interaction | Other students in class |

| |

| Partner work or partner interaction |

| |||

| Individual work |

| |||

| Physical state |

| |||

| Temperament of the child | Extroversion |

| ||

| Competence-related | Competence level | High competence level |

| |

| Subject-related | Maths |

| ||

| Duration/time |

|

| Main Category | Category | Sub-Category | Structure | Codes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students’ appraisals | Evaluation of the situation | Interest | Interest in subject |

|

| Interest in theme/activity |

| |||

| Type of task | Severity |

| ||

| Actuality of the game |

| |||

| Self-efficacy (self-assessment of own abilities) |

| |||

| Effort | Great effort |

| ||

| No effort |

| |||

| Importance of task |

| |||

| Coping resources available?/Coping possible? |

|

| M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | α | ω | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students’ appraisal | |||||||||||||||||

| 1. Appr Perf | 2.62 | 1.12 | 0.34 | 0.57 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.62 *** | 0.56 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.12 * | 0.06 | 0.27 *** | 0.11 ** | 0.18 *** | 0.04 | 0.14 ** | 0.28 *** |

| 2. Appr Learn | 2.16 | 1.02 | 0.80 | 0.02 | 0.76 | 0.76 | – | 0.42 *** | 0.56 *** | 0.25 *** | 0.05 | 0.36 *** | 0.21 *** | 0.18 *** | 0.08 | 0.15 ** | 0.23 *** |

| Students’ emotions | |||||||||||||||||

| 3. Emotions Perform | 2.49 | 0.88 | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.51 *** | 0.00 | 0.15 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.06 | 0.24 *** | 0.07 | 0.15 ** | 0.17 *** | ||

| 4. Emotions Learning | 2.14 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.50 | 0.78 | 0.78 | – | 0.10 * | 0.22 *** | 0.22 *** | 0.13 ** | 0.12 ** | 0.11 * | 0.05 | 0.11 *** | ||

| Students’ adaptive behaviour | |||||||||||||||||

| 5. Grit | 4.53 | 0.47 | 1.96 | 5.04 | 0.70 | 0.73 | – | 0.12 ** | 0.28 *** | 0.29 *** | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.11 * | 0.07 | |||

| 6. Problem solving | 3.76 | 1.57 | 0.75 | 0.62 | 0.72 | 0.82 | – | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.13 *** | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.12 ** | ||||

| Students’ maladaptive behaviour | |||||||||||||||||

| 7. Avoidance | 1.57 | 0.49 | 1.44 | 1.82 | 0.75 | 0.65 | – | 0.42 *** | 0.18 *** | 0.12 ** | 0.02 | 0.06 | |||||

| 8. Rebelliousness | 1.16 | 0.18 | 3.58 | 15.73 | 0.56 | 0.61 | – | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | ||||||

| Students’ desired teacher behaviour | |||||||||||||||||

| 9. Teacher support | 3.52 | 1.29 | 0.40 | 0.67 | 0.78 | 0.79 | – | 0.35 *** | 0.03 | 0.14 *** | |||||||

| 10. Teacher praise | 3.34 | 1.82 | 0.27 | 1.18 | 0.86 | 0.86 | – | 0.31 *** | 0.02 | ||||||||

| Covariates | |||||||||||||||||

| 11. Grade level | 5.47 | 1.40 | 0.09 | 1.50 | – | – | – | 0.04 | |||||||||

| 12. Gender | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schlesier, J.; Raufelder, D.; Ohmes, L.; Moschner, B. How Do Primary and Early Secondary School Students Report Dealing with Positive and Negative Achievement Emotions in Class? A Mixed-Methods Approach. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 582. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060582

Schlesier J, Raufelder D, Ohmes L, Moschner B. How Do Primary and Early Secondary School Students Report Dealing with Positive and Negative Achievement Emotions in Class? A Mixed-Methods Approach. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(6):582. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060582

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchlesier, Juliane, Diana Raufelder, Laura Ohmes, and Barbara Moschner. 2024. "How Do Primary and Early Secondary School Students Report Dealing with Positive and Negative Achievement Emotions in Class? A Mixed-Methods Approach" Education Sciences 14, no. 6: 582. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060582

APA StyleSchlesier, J., Raufelder, D., Ohmes, L., & Moschner, B. (2024). How Do Primary and Early Secondary School Students Report Dealing with Positive and Negative Achievement Emotions in Class? A Mixed-Methods Approach. Education Sciences, 14(6), 582. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060582