Abstract

We explored relationships between students’ shame-proneness and their experiences of state shame, self-regulation, and learning in a laboratory. We conducted two studies with different content: physics (Study 1, n = 179) and the circulatory system (Study 2, n = 85). We first evaluated students’ shame-proneness, self-regulation, and content knowledge (pretest). Then, half of the students participated in the experimental condition where state shame was induced. Subsequently, we evaluated students’ state shame and learning gains. In both studies, t-tests demonstrated that the experimental manipulation effectively induced higher levels of state shame. Follow-up 2 (experimental/control condition) by 2 (high/low shame-proneness) ANOVAs revealed that, in the experimental shame-induced condition, participants who had high shame-proneness had significantly higher state shame levels than those with low shame-proneness. Regarding students’ self-regulation, in both studies, high-shame-prone students had lower self-regulation skills. Interestingly, the outcomes of students’ learning gains differed in Studies 1 and 2. The results of a 2 (condition) by 2 (shame-proneness) ANOVA for Study 1 indicated no significant differences in students’ learning gains. In Study 2, participants in the experimental condition who reported high shame-proneness had significantly lower learning gains than those with low shame-proneness. We discuss several educational implications and provide directions for future research.

1. Introduction

“I made…a 78. I remember thinking that—I kind of wanted to crawl into a hole…. But I kind of had the feeling like, ‘You did it again. You could have done better, and you screwed up again.’ So, despite the fact that I was highly disappointed, I was kind of expecting myself to feel disappointed. Does that make sense?”.[1] (p. 83)

In the statement above, the student is describing her experience of academic shame when she received a grade that she perceived was a failure [1]. Her desire “to crawl into a hole” is a classic shame reaction [2] and illustrates her motivation to remove herself from the shame trigger. The student’s additional description of expecting to disappoint herself again suggests she may have a shame-prone disposition [3]. Shame-proneness is a dispositional trait whereby one tends to interpret evaluations as reflecting failure and condemnation. People with a shame-prone disposition tend to perceive failure and experience shame frequently [3]. Thus, the student above says to herself, “You did it again. You could have done better, and you screwed up again.” Tangney et al. [4] suggested that shame-prone individuals may be their own harshest critics—they may even evaluate themselves more negatively than they believe others do. Furthermore, research suggests that having a shame-prone disposition may negatively affect one’s functionality and adaptability [5,6,7,8]. For example, shame-proneness is linked with depression, a lack of empathy, a tendency to blame others, and expressions of anger and hostility [6,8].

Research has indicated that students experience shame in a variety of academic settings [9,10,11]. For example, Teimouri’s [11] research with students learning a second language showed that students’ shame experiences negatively affected their motivation and language achievements. Turner and Husman [2] explored students in a psychopharmacology course and found that, after experiencing state shame, students who were able to maintain their motivation used more learning-related and motivation-related self-regulation and subsequently increased their course grades, while students who were not able to maintain their motivation thought they could do nothing to increase their learning or motivation. However, these studies did not explore the extent to which students’ academic self-regulation habits and shame-prone dispositions might have interacted with their perceptions of failures, feelings of academic shame, and their learning. Considering the adverse consequences linked to shame, it is crucial to comprehend the precursors and consequences of students’ experiences of this emotion.

In our study, we assessed students’ shame-proneness and academic self-regulation tendencies and then induced state shame in an experimental laboratory setting. Our primary intent was to explore whether or not students’ shame-proneness may be related to their self-regulation, state shame, and learning. To provide the context of our study, we explain theory and research regarding these constructs.

1.1. State Shame

Most emotion theories agree that emotional experiences are multifaceted, involving coordinated affective, cognitive, physiological, motivational, and expressive components [12]. In our research, we were interested in the closely intertwined processes of emotion and cognition. One of the most powerful and distressing emotion–cognition combinations occurs with the emotion of shame. Shame is triggered when a person believes they have failed in an area that is important to them [13]. That is why shame is considered a self-conscious emotion [14,15]. With shame, a person experiences a negative evaluation of the self by the self, and because the failure is believed to be caused by a global, personal defect (I am awful), the emotion is particularly disturbing. In a moment of heightened self-awareness, a person feels they have irreparably failed, and there is nothing they can do to make up for it [16]. Because of the focus on a flawed self, feeling shame demands a “global reevaluation of the self” [17] (p. 45).

While a person’s cognitions focus on personal failure and being flawed, emotional concomitants include high arousal, feeling distressed, and a desire to withdraw and not talk with others [18]. Furthermore, theorists have proposed that shame acts as a powerful interrupt signal that disrupts cognitive functioning [14]. Because of the disruptive nature of shame, feeling shame may impact students’ ability to learn. Boekaerts [19] initially proposed that one way that negative emotions may affect students’ learning is by compromising their cognitive availability. She suggested that “situations that elicit strong emotions and a concern for well-being may be problematic in the sense that extra processing capacity is required for toning down emotions and for tuning back in on the tasks” (p. 151). Experiencing the emotion of shame may be particularly problematic for students’ well-being [19,20]. When feeling shame, tempering one’s emotions so that they can refocus on academic tasks may be particularly difficult because of the concomitant high arousal and distress, as well as feelings of self-doubt and withdrawal [9,10]. Although research has provided insights about the motivational consequences of feeling shame [9,10], research has not investigated whether or not feeling shame may impact students’ actual learning.

1.1.1. Lewis’ Appraisal Theory of Shame

Regarding the reason students may experience shame, first, our study aligns with Lewis’ [14] appraisal theory of shame initiation. Combining attribution theory and the importance of internalized standards, Lewis [14] proposed that shame occurs in the presence of four activities. First, an individual maintains standards, rules, and goals. Second, the individual must evaluate success or failure in relation to these standards. Third, the cause of the success or failure must be attributed to the self. Importantly, the failure must be perceived as reflecting globally on self-worth (as opposed to a specific behavior). To feel shame, a person must perceive that a failure to maintain valued standards or goals has happened, that the failure was due to the self, and that the failure represents a global aspect of low self-worthiness. Thus, following shame, we suspected that students’ ability to focus on learning may be impaired by their limited cognitive capacity [19]. Thus, students’ emotional experience of shame may be closely intertwined with their cognitive processes.

1.1.2. Pekrun’s Control–Value Theory

In addition to Lewis’ [14] notion of shame being caused by failure to meet important standards, our study also aligns with Pekrun’s [21] Control–Value Theory (CVT) of achievement emotions. Pekrun [21,22] proposed that achievement emotions can arise during any task related to goal-striving activities (e.g., studying, work, sports, etc.) or achievement outcomes (success and failure). The elicitors of achievement emotions are appraisals associated with perceptions of control and one’s values. Specifically, students’ appraisals of subjective control (e.g., causal expectancies, causal attributions, and competence appraisals) and subjective value (i.e., importance or relevance of actions or outcomes) determine their achievement emotions. In other words, achievement emotions are the result of a control–value interaction.

As a simple example, imagine a student who places a high subjective value on a task (e.g., an upcoming high-stakes exam) and experiences failure on the task (e.g., a low test grade). If this student believes that they were responsible for the outcome (i.e., internal locus of causality), the related achievement emotion may be shame. However, enjoyment of learning would occur when a student perceives that their control is high (e.g., perceived competence related to an expectation of success) and their value (perceived importance) is high. Most importantly, students’ emotions influence achievement behaviors and performances (e.g., reduced motivation, impaired strategies) [23]. The CVT has been influential in understanding how emotions impact students’ learning and academic performance. It emphasizes the dynamic interplay among cognitive appraisals (one’s perception of control) and one’s subjective value that elicit emotional experiences in achievement settings.

Although Pekrun’s Control–Value Theory [21,22] helps to explain the momentary trigger of state shame, researchers have not explored whether or not the trait of shame-proneness could be a contributing factor to students’ state shame experiences. Aligned with the CVT, students’ shame-proneness may represent ongoing appraisals of low control to obtain valued outcomes.

1.2. Shame-Proneness

Shame-proneness is a dispositional trait whereby one perceives failure and experiences shame frequently across situations [3]. With shame-proneness, individuals perceive they are the cause of their ongoing failures. Not surprisingly, shame-proneness is associated with elevated risks for other psychological issues, such as distress, anger, depression, low self-esteem, and hopelessness [24,25].

Regarding shame-proneness and academic behavior, Thompson and colleagues [26] found that, in an experimental study designed to indicate failure, high-shame-prone students (compared to low-shame-prone students) tended to report that they performed poorly, and they tended to rate their performances as failures. Subsequently, they attempted fewer tasks, even when they were given ‘face-saving’ explanations for their failures. The authors suggested that, because shame-prone students tend to interpret the cause of the poor outcomes to themselves and attribute the cause to a flaw in their character, they are not able to “take account of mitigating or ameliorating circumstances for the poor performance” (p. 625). As Thompson et al. [26] suggested, because shame-prone students attribute their failures to character flaws, they may feel that self-regulation is futile.

1.3. Self-Regulation

Research has demonstrated that high levels of positive and negative emotions deplete attentional resources because people focus their attention on the object of emotion [27]. Depleting attentional resources implies students have fewer cognitive resources to complete tasks, thereby negatively impacting performance [28]. Negative emotions such as shame or anxiety instigate extraneous thinking; thus, they reduce cognitive resources that students need to stay focused [27]. Boekaerts [29] suggested that students’ appraisals and emotions direct and redirect students’ ability to focus their attention to support their self-regulation.

Because we focused on students’ learning following shame experiences, we were interested in understanding associations between students’ shame-proneness and their ability to regulate their learning. Self-regulated learning involves self-directed and proactive processes that involve using cognitive abilities to promote academic performance [30,31]. In other words, students’ self-regulated learning refers to the processes through which they take control of their own learning. Self-regulated learners actively use adaptive skills, such as goal-setting, monitoring their learning, and evaluating their progress [31]. Regarding students’ proactive use of self-regulation skills, multiple studies have shown that students who use self-regulation skills tend to have higher academic achievement [32,33,34,35].

Given that one’s self-regulation is closely related to self-evaluation of performance [15], feeling shame could hamper students’ self-regulation skills. However, researchers have reported contrasting results regarding shame and self-regulation. For example, while Tangney and colleagues [25] found that, compared to feeling guilt, feeling shame was unlikely to motivate people to regulate themselves to improve, Lickel and colleagues [36] found that shame tended to motivate self-improvement. One possible explanation for these contrasting results is whether or not participants had shame-prone dispositions. If students are shame-prone, they may not try to self-regulate because they believe the flaw is a global and stable defect [26], and thus, they believe they are unable to improve.

To test this hypothesis, we explored the relationships between students’ shame-proneness and self-regulation skills and their ability to learn after shame induction. To capture moments of shame and understand its effects on learning, shame was induced through two experimental studies. We examined whether induced shame experiences negatively impacted students’ learning by comparing the results of pretest scores (i.e., before inducing shame) and posttest scores (i.e., after inducing shame). We also examined the influences of shame-proneness on students’ learning in the same experimental settings and explored the impact of students’ tendencies toward academic self-regulation. We investigated four hypotheses:

- Learners who receive the experimental manipulation will experience higher levels of state shame compared to learners who do not receive the manipulation.

- Learners with high shame-proneness will experience higher levels of state shame than students with low shame-proneness.

- Learners in the experimental manipulation who have high shame-proneness will learn significantly less than students who have low shame-proneness.

- Learners with high shame-proneness will have significantly lower self-regulation than students with low shame-proneness.

2. Materials and Methods of Study 1

We conducted two studies to examine the impacts of students’ shame-proneness on their state shame, learning, and self-regulation in different domains: conceptual knowledge of physics in Study 1 and the human circulatory system in Study 2. Participants were also different, and their subject knowledge was evaluated for pre/posttest learning gains.

2.1. Power Analysis

Two sets of power analyses were conducted through G*power to determine the minimum number of participants for each research question. More specifically, Table A1 in Appendix A shows the minimum number of participants when a t-test is conducted, which we used to answer research questions 1 and 4. To obtain 80% power with a large effect size (d = 0.8), the minimum number of participants is 52 in total. Table A2 in Appendix A shows the minimum number of participants when an ANOVA is conducted, which we used to answer research questions 2 and 3. To obtain 80% power with a large effect size (f = 0.4), the minimum number of participants is 52 in total.

2.2. Study 1 Participants

Participants were 179 students (90 in experimental; 89 in control—randomly assigned) who attended a private liberal arts university in the southern United States. Volunteers received extra credit in their general psychology class for their participation. A total of 45% of the participants were male, while 55% were female.

2.3. Materials

2.3.1. Test of Self-Conscious Affect (TOSCA-3)

Tangney and Dearing’s [3] Test of Self-Conscious Affect-3 (TOSCA-3) assesses one’s attributional tendencies that relate to being shame-prone, guilt-prone, prone to externalization, or prone to being unconcerned. It is composed of 16 scenarios that individuals may encounter. For example: “You make plans to meet a friend for lunch. At 5 o’clock, you realize you stood your friend up”. After considering the scenario, individuals are asked to consider the likelihood of four options that align with subscales (e.g., You would think “I’m inconsiderate”; You would think you should make it up to your friend as soon as possible), using a five-point rating scale (not likely = 1; very likely = 5). TOSCA-3 has demonstrated acceptable reliability for both the shame-proneness (α = 0.76) and guilt-proneness (α = 0.66) scales [37].

2.3.2. Self-Regulated Learning Self-Report Survey (SRL-SRS)

The SRL-SRS [38] is grounded in Zimmerman’s [39] theory of self-regulated learning. The survey gauges students’ consistent self-regulation across learning domains. It includes six subscales: planning, self-monitoring, evaluation, reflection, effort, and self-efficacy. An example of the planning subscale is: I determine how to solve a problem before I begin. The SRL-SRS has demonstrated satisfactory test-retest reliability along with construct and content validity [38]. The 50-item measure uses both 4-point (e.g., 1 = Almost Never; 4 = Almost Always) and 5-point Likert rating scales (e.g., 1 = Never; 5 = Always).

2.3.3. Experiential Shame Scale (ESS)

The Experiential Shame Scale (ESS) [18] is used to assess one’s in-the-moment state shame. The ESS is composed of eleven items where individuals specify the number that best reflects their current feelings when contrasting two opposite word states. For example, “Physically, I feel: Very Warm 1--2--3--4--5--6--7 Very Cool”. Previous research has found that the ESS has acceptable reliability (α = 0.72) along with convergent and discriminant validity [18].

2.3.4. Pretest/Posttest

The pretest and posttest consisted of 13 multiple-choice items designed to assess deep conceptual knowledge of physics. The two tests were developed by an associate professor of physics who was involved with the project. The physics professor designed the test to cover topics that are traditionally covered in an introductory physics course, thus demonstrating content validity. The order of the tests (i.e., pretest/posttest) was counterbalanced to prevent any order effects (see Figure A1 in Appendix B for an example from the physics learning assessment). An example question is: Which characteristic of a wave changes as the wave travels across a boundary between two different materials? (options: A. frequency; B. period; C. type of wave; D. speed).

2.3.5. Aptitude Test

As part of the experimental manipulation, participants completed an “aptitude test” composed of 17 ACT practice problems (quantitative and qualitative). The practice problems were obtained from the ACT website “act.org (accessed on 2 October 2018)”. An example question was: A DVD player with a list price of $100 is marked down 30%. If John gets an employee discount of 20% off the sale price, how much does John pay for the DVD player? (options: A. $86.00; B. $77.60; C. $56.00; D. $50.00; E. $44.00). It warrants mentioning that the participants did not know that the problems were practice ACT problems. They were simply told that the test was an aptitude assessment that was predictive of their overall intelligence.

2.4. Procedure

Prior to entering the laboratory, participants were randomly assigned to either the experimental group (involving shame induction) or the control group. Following the completion of the informed consent process, participants were administered the TOSCA-3. They then completed a physics pretest (version A or B; counterbalanced) and the Self-Regulation Scale. Before beginning the aptitude test, participants were read the following instructions:

“During this portion of the study, you will be asked to complete a series of problems. These are problems that, as a college student, should not be extremely challenging for you. Additionally, it is important to note that the upcoming test has been shown to predict your overall intelligence. To recreate a scenario that would match an actual testing environment, you will have 30 min to complete the test. After you submit the test, instructions will appear on the screen that will let you know the next steps you will need to take in this study. Please let the experimenter know if you have any questions at this time. Thank you again for your participation!”

The only distinction between what was read to participants in the control group and the experimental group lies in the bolded portion of the instructions; the experimental group received the bolded statement. Furthermore, for the experimental (i.e., shame induction) group, after finishing the aptitude test, a text box appeared stating:

“Your combined score on the test was: 40%. The average [school name] student scored 90%. Please let the experimenter know your score so it can be cataloged.”

After completing the ACT practice problems, the control group received the following feedback in a text box on the computer screen:

“You have now completed this portion of the study. Please let the experimenter know you are ready to proceed.”

This shame induction procedure was used for two reasons: (1) previous research has shown that learning (i.e., low test grades) is an event that sparks a shame reaction [40], and (2) this procedure has been shown to be effective at inducing shame in previous studies [41].

After finishing the aptitude test, participants completed the Experiential Shame Scale (ESS) to assess their level of in-the-moment state shame. After completing the ESS, participants watched a multimedia video (i.e., learning intervention) to learn about waves (i.e., physics content) and to determine the impact of state shame on learning (see Figure 1 for a screenshot of the video). The content of the video was developed by an associate professor of physics affiliated with the current project.

Figure 1.

Screenshot of the learning intervention video.

Following the video, participants were given the physics posttest (version A or B, counterbalanced) that contained information covered in the learning intervention video. We used students’ posttest scores to determine the amount of physics content they learned and to determine if students’ learning was impacted by experiencing state shame. Participants were then debriefed and left.

3. Results of Study 1

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 29 [42]. Initially, to explore whether our experimental manipulation effectively induced higher levels of state shame, we conducted an independent sample t-test, using condition (experimental versus control) as the independent variable and state shame (ESS) scores as the dependent variable. Results showed that participants in the experimental condition (M = 4.12) had significantly higher levels of state shame than participants in the control condition (M = 3.42), t(177) = 5.05, p < 0.001, d = 0.76.

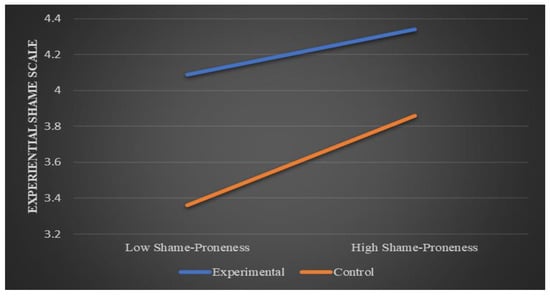

3.1. State Shame and Shame-Proneness

A two (high/low shame-proneness) by two (experimental/control condition) ANOVA was conducted with ESS scores as the dependent variable. While all participants in the experimental condition had higher state shame than participants in the control condition, Figure A2 in Appendix B shows that participants with high shame-proneness in the experimental condition had significantly higher levels of state shame (M = 4.26) than participants with high shame-proneness in the control condition (M = 3.50, p < 0.001). Additionally, participants in the experimental condition with low shame-proneness (M = 3.90) had significantly higher levels of state shame compared to participants in the control condition with low shame-proneness (M = 3.33, p = 0.007).

3.2. Learning-Gains

A two (experimental/control condition) by two (high/low shame-proneness) ANOVA was conducted using students’ learning gains (posttest minus pretest) as the dependent measure. Results demonstrated no main effect for condition: F(1, 175) = 0.018, p = 0.893, or shame-proneness: F(1, 175) = 1.27, p = 0.262. Lastly, no significant condition by shame-proneness interaction was discovered: F(1, 175) = 0.472, p = 0.493. However, an inspection of all pretest and posttest scores suggested that the material was too difficult for all students to learn. The average pretest score for students in the control group was 42%, and it was 44% for those in the experimental group. The average posttest score for those in the control group was 50%, and it was 49% for those in the experimental group.

3.3. Shame-Proneness and Self-Regulation

We used an independent sample t-test to investigate the relationship between students’ shame-proneness and self-regulatory strategies, using shame-proneness (high versus low) as the independent variable and total self-regulation scores as the dependent variable. Results showed that participants in the experimental group demonstrated significantly lower total self-regulation scores (M = 126.96) compared to participants in the control condition (M = 138.93), t(177) = 2.493, p = 0.01, d = 0.37. Moreover, participants with high shame-proneness had significantly lower total self-regulation (M = 128.45) compared to participants with low shame-proneness (M = 139.09), t(177) = 2.25, p = 0.026, d = 0.34. Specifically, further analysis revealed that participants with high shame-proneness had significantly lower scores on personal control (M = 13.72) compared to participants with low shame-proneness (M = 16.03, p = 0.029). Participants with high shame-proneness also had significantly lower self-monitoring (M = 13.60) compared to students with low shame-proneness (M = 15.92, p = 0.014), as well as lower reflection (M = 16.72, p = 0.027). Lastly, participants with high shame-proneness had significantly lower self-efficacy (M = 25.03) than participants with low shame-proneness (M = 27.36, p = 0.002).

3.4. Summary of Study 1

The results from Study 1 demonstrated that our shame induction manipulation effectively induced higher levels of state shame, particularly for those students who had high shame-proneness. However, we found no differences in students’ learning gains, perhaps because the topic was quite difficult. Thus, we may have had a floor effect on students’ physics knowledge gains (average pretest scores were 43%; average posttest scores were 49%). Interestingly, we found that high-shame-prone students had lower self-regulation skills, particularly with personal control, self-monitoring, reflection, and self-efficacy. To confirm our results and further investigate the impact of shame on students’ learning, we conducted a second study using a topic that was complex but less difficult to learn: the human circulatory system.

4. Materials and Methods of Study 2

Our goal for Study 2 was to replicate and extend the effects of shame (state and trait) on self-regulation and learning gains with different participants on a less difficult topic (the circulatory system). We used the same materials to measure students’ shame-proneness (TOSCA-3) [3], self-regulation (SRL-SRS) [38], and state shame (ESS) [18].

4.1. Participants

Participants were 85 students (43 in experimental; 42 in control—randomly assigned) from a private liberal arts university in the southern United States. Volunteers received extra credit in their general psychology class for their participation.

4.2. Materials

4.2.1. Pretest/Posttest

To evaluate students’ understanding of the human circulatory system, the authors developed three tests. The first test included 10 multiple-choice items focusing on the human circulatory system. For example, “the process of circulation includes which of the following: (a) the intake of metabolic materials; (b) the convergence of metabolic materials throughout the organism; (c) the return of harmful by-products to the environment; (d) all of the above”. The second test, composed of 20 matching items, required participants to accurately identify components of the human heart. Finally, the third test included 13 matching items, tasking participants with correctly labeling parts of the human circulatory system. For example, “Which part of the human circulatory system carries blood away from the heart?” (Answer: arteries).

4.2.2. Aptitude Test

As part of the experimental manipulation, participants completed an “aptitude test” composed of 17 ACT practice problems (quantitative and qualitative). The practice problems were obtained from the ACT website “act.org (accessed on 2 October 2018)”.

4.3. Procedure

Prior to entering the laboratory, participants were randomly assigned to either the experimental group (involving shame induction) or the control group. Following the completion of the informed consent process, participants were administered the TOSCA-3. They then completed the three tests of the circulatory system and, subsequently, the Self-Regulation Scale. Then, before beginning the aptitude test, participants were read the following instructions:

“During this portion of the study, you will be asked to complete a series of problems. These are problems that, as a college student, should not be extremely challenging for you. Additionally, it is important to note that the upcoming test has been shown to predict your overall intelligence. To recreate a scenario that would match an actual testing environment, you will have 30 min to complete the test. After you submit the test, instructions will appear on the screen that will let you know the next steps you will need to take in this study. Please let the experimenter know if you have any questions at this time. Thank you again for your participation!”

The only distinction between what was read to participants in the control group and the experimental group lies in the bolded portion of the instructions; the experimental group received the bolded statement. Furthermore, for the experimental (i.e., shame induction) group, after finishing the aptitude test, a text box appeared stating:

“Your combined score on the test was: 40%. The average [school name] student scored 90%. Please let the experimenter know your score so it can be cataloged.”

After completing the ACT practice problems, the control group received the following feedback in a textbox on the computer screen:

“You have now completed this portion of the study. Please let the experimenter know you are ready to proceed.”

After finishing the ACT practice problems and providing their scores to the researcher (in the experimental condition), participants were tasked with completing the Experiential Shame Scale to gauge their level of state shame. Following this, they interacted with a hypermedia encyclopedia, which functioned as our instructional delivery. Before engaging with the encyclopedia, the experimenter read the following instructions:

You are being presented with a hypermedia encyclopedia, which contains textual information, static diagrams, and digitized video clips. We are trying to learn more about how students use hypermedia environments to learn about the circulatory system. Your task is to learn all you can about the circulatory system in 30 min. Make sure you learn about the different parts and their purpose, how they work individually and together, and how they support the human body. I’ll be here if anything goes wrong with the computer or the equipment. Thank you again for your participation!

Participants had to use the entire 30 min allocated before progressing to the next phase of the study. All audio and video were recorded during this portion of the experiment. After using the encyclopedia, participants completed the circulatory system posttests (same as the pretests), debriefed, and left.

5. Results of Study 2

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 29 [42]. We used an independent sample t-test to determine whether our experimental manipulation effectively induced higher levels of state shame, using condition (experimental versus control) as the independent variable and ESS scores as the dependent variable. Results revealed that participants in the experimental condition (M = 4.26) had significantly higher ESS scores compared to participants in the control condition (M = 3.68), t(83) = 2.939, p = 0.004, d = 0.64.

5.1. State Shame and Shame-Proneness

We used a two (high/low shame-proneness) by two (experiment/control condition) ANOVA to explore interactions between students’ shame-proneness (high/low) and the experimental conditions, with state shame (ESS) scores as the dependent variable. Figure A3 in Appendix B shows participants in the experimental condition with high shame-proneness (M = 4.34) had significantly higher state shame scores than participants in the control condition with high shame-proneness (M = 3.87, p = 0.04), further suggesting that our manipulation was effective, particularly for high-shame-prone students. Interestingly, participants in the experimental condition with low shame-proneness (M = 4.09) had significantly higher state shame scores than participants in the control condition with low shame-proneness (M = 3.37, p = 0.05).

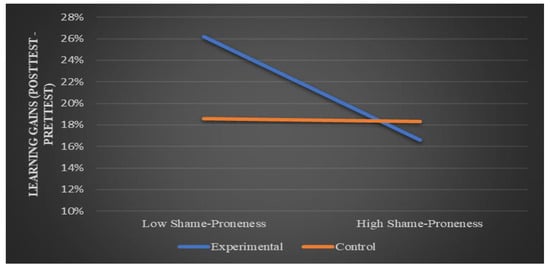

5.2. State Shame, Shame-Proneness, and Learning Gains

To explore the impact of state shame and shame-proneness on students’ learning, we conducted a two (high/low shame-proneness) by two (experimental/control condition) ANOVA with students’ learning gains as the dependent measure. Figure A4 in Appendix B shows that (1) within the control condition, high and low-shame-prone participants did not have statistically different scores on the posttest; however, (2) within the experimental condition, participants who were low-shame-prone had significantly higher learning gains (M = 26.2%) compared to participants who were high-shame-prone (M = 16.6%, p = 0.04).

5.3. Self-Regulation

To investigate differences in self-regulatory strategies for students with low and high shame-proneness, we conducted an independent sample t-test using shame-proneness (high versus low) as the independent variable and total self-regulation as the dependent variable. Results showed that participants with high shame-proneness had significantly lower total self-regulation scores (M = 142.96) compared to participants with low shame-proneness (M = 150.64), t(82) = 1.94, p = 0.05, d = 0.46. Additional analysis demonstrated significant differences between participants with high and low shame-proneness regarding their self-efficacy: t(82) = 2.21, p < 0.05, d = −0.53, learning reflection: t(82) = 2.30, p < 0.05, d = 0.55, and effort: t(82) = 2.02, p < 0.05, d = 0.48. Participants with high shame-proneness were less likely to (1) have strong self-efficacy beliefs (M = 26.36), (2) reflect on their learning (M = 18.56), and (3) put effort into learning (M = 27.20), compared to those with low shame-proneness (respectively, M = 28.08; M = 20.92; M = 29.84).

6. General Discussion

Before moving on to the general discussion of our study, we would like to acknowledge limitations regarding interpreting our findings. Although results from Studies 1 and 2 revealed that learners assigned to the shame-induction condition did have significantly higher state shame scores compared to those not in the shame-induction condition, these results should be interpreted with caution. Across both studies, learners in the shame-induction condition who were not shame-prone averaged a state shame score of 4.00 (minimum 2.09–maximum 5.91) out of a possible 7.00, while shame-prone students in the shame-induction conditions averaged a state shame score of 4.28 (minimum 2.18–maximum 6.18). Although our measure of state shame (i.e., the Experiential Shame Scale) is a valid and reliable measure, based on the data, it is difficult to assert that we were measuring state shame alone in the strictest sense.

Additionally, while dichotomizing variables may diminish the power of statistical analyses as well as reduce the variability of measures, it facilitates an effective separation of distinct groups that hold theoretical and practical significance, especially concerning potential intervention implications [43]. Furthermore, because high shame-proneness was our focus, we used an ANOVA approach that aligned with previous research exploring this construct [44].

Despite the limitations, our findings provide insight into ways that students’ dispositional shame-proneness influences their perceptions of failure information, experiences of state shame, self-regulation tendencies, and the ultimate consequences of their learning. As we explain below, our findings are aligned with previous research regarding self-verification [45,46], academic self-regulation [2,26], and learning [47].

6.1. Shame-Proneness and Self-Verification

The results from both studies underscore the influence that shame-proneness can have on students’ emotional reactions to ‘failure’ feedback. Compared to low-shame-prone students, students who are high in shame-proneness may interpret failure information as reflecting personal and global flaws [26]. This failure information may provide confirmation that one is “a failure” [45]. Research has shown that people seek information that confirms their self-views—even if their self-views are unfavorable [45,46]. Self-verification is important because it “provides psychological coherence, a feeling that oneself and the world are as expected” (p. 132) [48]. According to Swann and Brooks [46], when external information does not align with self-perceptions, people feel anxious. For example, Prislin and Wood [49] found that students who had low self-esteem felt anxious after having success because the information was inconsistent with their self-views.

Particularly in Study 2, our high-shame-prone students likely interpreted the initial failure feedback as indicating, again, that they are “a failure” and/or that they have low academic ability. Thus, the failure feedback verified their self-conceptions. They subsequently experienced state shame and difficulties with learning circulatory information.

On the other hand, when the low-shame-prone students received failure feedback, it did not fit with their self-conceptions. Their reaction was to put forth effort in learning the circulatory information to demonstrate their academic ability to themselves and others. Consequently, they demonstrated the highest learning across all groups (low/high shame-proneness, experimental/control conditions). This aligns with Swann’s [45] description of people’s reactions to receiving information that does not conform to their self-conceptions: “after they recover from their surprise, people will often rush to find ways to discredit or dismiss the feedback” (p. 33). Our findings suggest that the failure feedback confirmed the self-views of high-shame-prone students but was dissonant with the self-views of low-shame-prone students. The dissonance could have made them feel uncomfortable; thus, they may have been eager to demonstrate their academic ability. Future research could further explore the relationships between shame-proneness and self-verification, particularly investigating the cognitive processes that shame-prone students use for interpreting feedback information.

6.2. Shame-Proneness and Self-Regulation

Perhaps because of self-verification processes, having a shame-prone disposition may render students more vulnerable regarding the negative effects of perceived failure. For example, individuals who are high in shame-proneness may likely attribute their poor performance to permanent inadequacies with their abilities that would be difficult to change [26]. In particular, our results demonstrated that high-shame-prone students had lower academic self-efficacy (i.e., not believing they had skills and could use their skills to obtain desired outcomes). Research has consistently shown that when students had low academic self-efficacy, they tended to be less persistent [50]. Thompson et al. [26] found that, after failure feedback, students who were shame-prone exerted less effort to problem-solve than students who were not shame-prone, even when they were given face-saving information.

Along with having low self-efficacy, one important aspect of our findings was that shame-prone students had lower self-regulation resources. These findings are congruous with Turner and Husman’s [2] observations that, after experiencing academic shame, non-resilient learners (those who did not increase later test scores) diverged dramatically in their regulation of effort and approaches to studying, compared to those students who were resilient (increased later test scores). Consistent across both studies, we found that high-shame-prone students tended to have lower scores for self-efficacy and for conducting learning-related reflections.

For students who are shame-prone, not reflecting on ways to improve presents additional problems for their academic attainment. Being able to reflect on their approaches to learning is important for students’ adaptability (i.e., self-regulation that focuses on adjustments and modifications) [51], particularly learning from their mistakes [52]. If students are not metacognitively reflective, they may not focus on problem-solving and may not be able to adapt to college demands [53]. Indeed, shame-prone students may interpret their errors as confirming their low ability, which justifies their low self-efficacy. The ability to regulate one’s effort is an important variable in predicting college students’ course grades [54,55]. Students who are shame-prone may see their academic flaws as being out of their control, which justifies their low self-efficacy and low self-reflection and may inhibit their academic effort. In a vicious cycle, their low effort would impact their achievement, and their low achievement would confirm their low ability, thus inhibiting further positive self-efficacy and self-reflection.

In contrast to high-shame-prone students’ lack of self-regulation resources, students in the experimental condition (Study 2) who were low shame-prone indicated they had higher academic self-efficacy and higher learning-related reflections, and they demonstrated they were willing to put forth effort in academic learning. Thus, after they received a low score on the general achievement test, they seemed energized to adapt, exert effort, and demonstrate their learning ability. Future research could explore if providing shame-prone students with self-regulation resources could improve their repertoire of learning-related and motivation-related strategies and their ability to reflectively adapt their approaches in different situations.

6.3. Shame-Proneness and Learning

In Study 2, we found that in the experimental condition, students who were shame-prone learned less than students who were not shame-prone. As discussed above, their lower scores could be related to having fewer self-regulatory resources. Pekrun et al. [47] and Boekaerts [19] suggested that students’ experiences of state shame and related emotions of hopelessness and anxiety may “erode motivation, direct attention away from the task, and make any processing of task-related information shallow and superficial” (p. 98). Thus, when students experience shame, their cognitive engagement may be impaired; furthermore, their motivation for studying may diminish [1]. Turner and Husman [2] found that, compared to resilient shame-experiencing students, non-resilient shame-experiencing students tended to use fewer learning strategies and tended to use shallow memory-based strategies such as reviewing notes and making flashcards, while resilient students used more types of learning strategies and used strategies that supported deeper learning, such as making connections across sources of information.

In addition to using surface learning strategies, Teimouri [11] suggested that, during experiences of shame, students may split their attention between focusing on themselves and focusing on learning; therefore, attentional resources for academic learning may be depleted. Future research should explore these relationships with an eye toward developing strategies to intervene in the cognitive disruptions of experiencing shame.

6.4. Suggestions for Interventions

Our findings suggest that, compared to students who are not shame-prone, students who are shame-prone react differently to failure feedback. In addition to providing shame-prone students with a repertoire of learning strategies and self-regulation strategies, two interventions may help shame-prone students’ ability to self-reflect and interpret feedback information—attributional retraining and practicing self-compassion.

6.4.1. Attributional Retraining

In an extensive meta-analysis, Richardson et al. [55] revealed that, among 50 predictors, the strongest predictor of college students’ GPA was self-efficacy (i.e., the belief that they have control over and expect positive learning outcomes). Their findings underscore the significance of students’ perceptions that they can confidently influence academic outcomes. Aligned with Weiner’s [56,57] attribution theory, shame-prone students may be susceptible to attributing feedback information as indicating their failure is caused by reasons that are internal (vs. external), not controllable (vs. controllable), and stable (vs. changeable), such as low aptitude. This pattern of attributions is maladaptive because students believe that poor outcomes are their fault and that they can do nothing to improve their performance. A more adaptive attributional pattern would be believing that, while the cause of an outcome is due to personal reasons, the student can make changes (controllable and changeable) that could impact future performance. Attributional retraining is “designed to modify students’ attributional schemas and encourage adaptive attributions for failure” [58] (p. 199). Attributional retraining particularly focuses on having students make attributions for failures that are internal yet unstable and controllable [59]. Research has shown that attributional retraining increased students’ focus on mastering material instead of focusing on performance outcomes, which was a primary mediator for raising students’ GPA [58].

Furthermore, attributional retraining promoted higher grade expectations and higher academic performances for students who had been identified as avoiding academic failure [60]. Perhaps most importantly, Hamm et al. [61] revealed that attributional retraining particularly helped students who were identified as failure-ruminators (high failure preoccupation, low perceived control) and failure-acceptors (low failure preoccupation, low perceived control). They found that, even after five months, students who participated in attributional retraining indicated “adaptive causal thinking in which uncontrollable attributions are either downplayed” or “controllable attributions are emphasized” (p. 232). Thus, we believe that attributional retraining may help shame-prone students develop perceptions of control that would help promote their academic achievement and their well-being.

6.4.2. Self-Compassion

Along with attributional retraining, shame-prone students might benefit from learning to have self-compassion. Neff [62] explained that self-compassion:

Involves being touched by and open to one’s own suffering, not avoiding or disconnecting from it, and generating the desire to alleviate one’s suffering and to heal oneself with kindness. Self-compassion also involves offering nonjudgmental understanding of one’s pain, inadequacies, and failures so that one’s experience is seen as part of the larger human experience.(p. 87)

Having self-compassion does not mean that one is complacent with one’s perceived faults. Instead, self-compassion “provides the emotional safety needed to see the self clearly without fear of self-condemnation, allowing the individual to more accurately perceive and rectify maladaptive patterns of thought, feeling, and behavior” [62] (p. 87). Supporting the idea that college students’ self-compassion is important for their well-being, Neely et al. [63] found that students’ self-compassion predicted their positive mental health.

Neff et al.’s [64] study with college students revealed that, compared to students who had low self-compassion, students who had high self-compassion tended to (1) focus more on mastering material (instead of focusing on performance outcomes), (2) have a lower fear of failure, and (3) have higher perceptions of competence. They also found that, after academic failures, students who had high self-compassion tended to focus on reducing negative emotions and did not engage in avoidance behaviors. Furthermore, Martin et al. [65] found that college students who had high academic self-compassion also had higher ratings of adaptation (adjustment to university life) as well as higher ratings of academic resourcefulness (e.g., time management and use of learning strategies). Interventions that focus on promoting students’ self-compassion have demonstrated that self-compassion is teachable [66,67]. We suspect that students who are high in shame-proneness would benefit from interventions that promote self-compassion, along with attributional retraining.

6.4.3. Online Education

One area ripe for further research is the impact of online education on students’ experiences of state shame. This question is paramount given that many colleges have transitioned to online education following the COVID-19 pandemic. More specifically, according to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), in spring 2020 in the United States, 77% of public schools and 73% of private schools reported moving some or all classes to online-only delivery [68]. Additionally, 84% of college students reported that some or all classes were moved to online-only instruction [69]. Previous research has discovered an association between emotions and distance education [70,71,72,73]. For example, Pirrone et al. [74] found that online instruction led to a decrease in anxiety. They claimed that the structured nature of online courses may help reduce students’ anxiety. This raises a question about students’ feelings of shame in regular classes versus online classes. Would students experience less shame in online classes than in regular classes? Although shame can be experienced in both public and private situations [4], research has shown that education-based social situations (e.g., experiencing mistreatment and underrepresentation) can serve as shame triggers and promoters [75]. Future research is warranted regarding whether the same effects found in our study would be replicated in online education.

7. Conclusions

Our research suggests that shame-prone students may be particularly vulnerable to perceptions of failure and low self-efficacy. They tended to be less reflective, less likely to use self-regulation resources, and put forth less effort in their studies. These factors alone can hinder students’ abilities to adapt to shifting academic contexts. Most importantly, our findings suggest that shame-prone students are particularly vulnerable to feedback on failure. For these students, perceived criticism or perceived failure feedback may confirm their negative self-views and instantiate feelings of state shame. With state shame, these students may experience heightened self-consciousness [76], causing their attention to be split between their self-focus and the demands of academic tasks [11]. While we do not know how our shame-prone students processed information, we do know that, after shame induction, the shame-prone students demonstrated the highest state shame and the lowest learning gains. More research could provide a better understanding of this vulnerable population as well as ways to provide them with effective interventions. All learning requires effort and the purposeful integration of knowledge [77]. As educators, we want all students to feel capable of learning and to have the cognitive and emotional resources that allow them to be reflective and adaptive, so they may accomplish their valued academic and life goals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S., J.T. and J.K.; methodology, J.S., J.T. and J.K.; software, J.S.; formal analysis, J.S.; investigation, J.S. and S.B.; data curation, J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S. and J.T.; writing—review and editing, J.K.; visualization, J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with APA ethical standard 8, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Harding University (proposal number 2020-001 with a 2/4/2020 date of approval).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The minimum sample size for the t-test.

Table A1.

The minimum sample size for the t-test.

| Effect Size (d) | Power | Minimum Sample Size in Total |

|---|---|---|

| 0.8 | 0.8 | 52 |

Table A2.

Minimum sample size for ANOVA.

Table A2.

Minimum sample size for ANOVA.

| Number of Groups | Numerator df | Effect size (f) | Power | Minimum Sample Size in Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 1 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 52 |

Appendix B

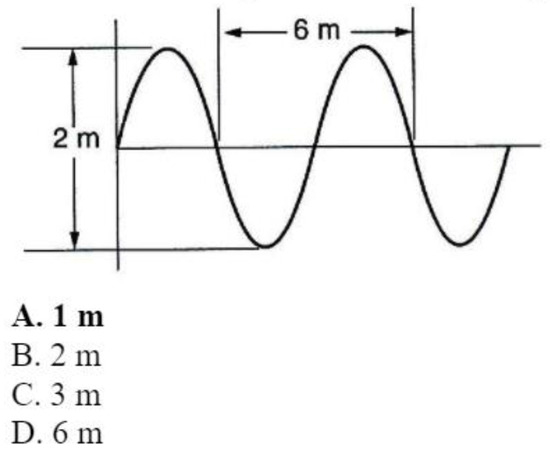

Q. What Is the Amplitude of the Wave Represented in the Diagram?

Figure A1.

An example from the physics learning assessment.

Figure A2.

Condition by Shame Proneness Interaction with ESS Scores as the Dependent Variable.

Figure A3.

Condition by Shame Proneness on State Shame after Shame Induction.

Figure A4.

Condition by Shame Proneness Interaction with Learning Gains as the Dependent Variable.

References

- Turner, J.E.; Husman, J.; Schallert, D.L. The importance of students’ goals in their emotional experience of academic failure: Investigating the precursors and consequences of shame. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 37, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.E.; Husman, J. Emotional and cognitive self-regulation following academic shame. J. Adv. Acad. 2008, 20, 138–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J.P.; Dearing, R.L. Shame and Guilt; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney, J.P.; Wagner, P.E.; Hill-Barlow, D.; Marschall, D.E.; Gramzow, R. Relation of shame and guilt to constructive versus destructive responses to anger across the lifespan. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 797–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budiarto, Y.; Helmi, A.F. Shame and Self-Esteem: A Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Psychol. 2021, 17, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kämmerer, A. The Scientific Underpinnings and Impacts of Shame. Scientific American. 2019. Available online: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-scientific-underpinnings-and-impacts-of-shame/ (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Stuewig, J.; Tangney, J.P.; Kendall, S.; Folk, J.B.; Meyer, C.R.; Dearing, R.L. Children’s Proneness to Shame and Guilt Predict Risky and Illegal Behaviors in Young Adulthood. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2015, 46, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tignor, S.M.; Colvin, C.R. The Interpersonal Adaptiveness of Dispositional Guilt and Shame: A Meta-Analytic Investigation. J. Pers. 2017, 85, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galmiche, D. The Role of Shame in Language Learning. J. Lang. Texts Soc. 2018, 2, 99–129. [Google Scholar]

- Huff, J.L.; Okai, B.; Shanachilubwa, K.; Sochacka, N.W.; Walther, J. Unpacking professional shame: Patterns of white, male engineering students living in and out of threats to their identities. J. Eng. Educ. 2021, 110, 414–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teimouri, Y. Differential roles of shame and guilt in L2 learning: How bad is bad? Mod. Lang. J. 2018, 102, 632–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuman, V.; Scherer, K.R. Concepts and structures of emotions. In International Handbook of Emotions in Education; Pekrun, R., Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 13–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bynum IV, W.E.; Varpio, L.; Lagoo, J.; Teunissen, P.W. ‘I’m Unworthy of Being in This Space’: The Origins of Shame in Medical Students. Med. Educ. 2021, 55, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M. Self-conscious emotions: Embarrassment, pride, shame, and guilt. In Handbook of Emotions; Lewis, M., Haviland-Jones, J.M., Barrett, L.F., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 742–756. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, J.L.; Robins, R.W. Putting the self in the self-conscious: A theoretical model. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, C.W. Understanding Shame and Guilt. In Handbook of the Psychology of Self-Forgiveness; Woodyatt, L., Worthington, E., Jr., Wenzel, M., Griffin, B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Probyn, E. Blush: Faces of Shame; Minnesota University Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.E. Researching state shame with the experiential shame scale. J. Psychol. 2014, 148, 577–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boekaerts, M. Being concerned with well-being and with learning. Educ. Psychol. 1993, 28, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.N.; Fallah, N. Academic Burnout, Shame, Intrinsic Motivation, and Teacher Affective Support Among Iranian EFL Learners: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 2026–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 18, 315–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R.; Frenzel, A.C.; Goetz, T.; Perry, R.P. The control-value theory of achievement emotions: An integrative approach to emotions in education. In Emotion in Education; Elsevier Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 13–36. [Google Scholar]

- Pekrun, R.; Marsh, H.W.; Elliot, A.J.; Stockinger, K.; Perry, R.P.; Vogl, E.; Goetz, T.; Van Tilburg, W.A.; Lüdtke, O.; Vispoel, W.P. A three-dimensional taxonomy of achievement emotions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 124, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineles, S.L.; Street, A.E.; Koenen, K.C. The differential relationships of shame-proneness and guilt-proneness to psychological and somatization symptoms. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 6, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J.P.; Wagner, P.; Gramzow, R. Proneness to shame, proneness to guilt, and psychopathology. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1992, 101, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, T.; Altmann, R.; Davidson, J. Shame-proneness and achievement behaviour. Person. Indiv. Differ. 2004, 36, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boekaerts, M.; Pekrun, R. Emotions and Emotion Regulation in Academic Settings. In Handbook of Educational Psychology; Corno, L., Anderman, E.M., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 76–90. [Google Scholar]

- Meinhardt, J.; Pekrun, R. Emotion and memory. In Handbook of Emotions, 2nd ed.; Lewis, M., Haviland-Jones, J.M., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 476–490. [Google Scholar]

- Boekaerts, M. Self-regulation and effort investment. In Handbook of Child Psychology; Renninger, K.A., Sigel, I.E., Damon, W., Lerner, R.M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 4, pp. 345–377. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Development and adaptation of expertise: The role of self-regulatory processes and beliefs. In The Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; pp. 705–722. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Investigating self-regulation and motivation: Historical background, Methodological developments, and future prospects. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2008, 45, 166–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, K.; Tohmaz, R.; Jabak, O. The relationship between self-regulated learning and academic achievement for a sample of community college students at King Saud University. Educ. J. 2017, 6, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ergen, B.; Kanadli, S. The effect of self-regulated learning strategies on academic achievement: A meta-analysis study. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 2017, 17, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nota, L.; Soresi, S.; Zimmerman, B.J. Self-regulation and academic achievement and resilience: A longitudinal study. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2004, 41, 198–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D.H. Commentary on self-regulation in school contexts. Learn. Instruc. 2005, 15, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lickel, B.; Kushlev, K.; Savalei, V.; Matta, S.; Schmader, T. Shame and the motivation to change the self. Emotion 2014, 14, 1049–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangney, J.P.; Dearing, R.L.; Wagner, P.E.; Gramzow, R. The Test of Self-Conscious Affect-3 (TOSCA-3); George Mason University Press: Fairfax, VA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Toering, T.; Elferink-Gemser, M.T.; Jonker, L.; van Heuvelen, M.J.G.; Visscher, C. Measuring self-regulation in a learning context: Reliability and validity of the Self-Regulation of Learning Self-Report Scale (SRL-SRS). Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2012, 10, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J.; Schunk, D.H. Handbook of Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bynum, W.E., IV; Uijtdehaage, S.; Artino, A.R., Jr.; Fox, J.W. The Psychology of Shame: A Resilience Seminar for Medical Students. MedEdPORTAL 2020, 16, 11052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullins, J.; Console, K.; Henrichson, C.; Denton, R.; Roberts, S.; Howell, K. The First Step in Harnessing the Self-Conscious Emotions: A Quantitative Exploration of Shame. In Proceedings of the CogSci, Madison, WI, USA, 25–28 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- IBM. SPSS Statistics; IBM: Chicago, IL, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/release-notes-ibm®-spss®-statistics-29 (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Hall, N.C.; Perry, R.P.; Chipperfield, J.G.; Clifton, R.A.; Haynes, T.L. Enhancing primary and secondary control in achievement settings through writing–based attributional retraining. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 25, 361–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilodeau, C.; Savard, R.; Lecomte, C. Examining Supervisor and Supervisee Agreement on Alliance: Is Shame a Factor? Can. J. Couns. Psychother. 2010, 44, 272–282. [Google Scholar]

- Swann, W.B. Self-Verification: Bringing Social Reality into Harmony with the Self. In Social Psychological Perspectives on the Self, 2nd ed.; Suls, J., Greenwald, A.G., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1983; Volume 2, pp. 33–66. [Google Scholar]

- Swann, W.B.; Brooks, M. Why threats trigger compensatory reactions: The need for coherence and quest for self-verification. Soc. Cognit. 2012, 30, 758–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R.; Goetz, T.; Titz, W.; Perry, R.P. Academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: A program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 37, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, R.J.; Swann, W.B., Jr. Self-verification 360: Illuminating the light and dark sides. Self Identity 2009, 8, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prislin, R.; Wood, W. Social Influence in Attitudes and Attitude Change. In The Handbook of Attitudes; Albarracín, D., Johnson, B.T., Zanna, M.P., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 671–705. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, D.; Fan, W.; Zou, Y.; George, R.A.; Arbona, C.; Olvera, N.E. Self-Efficacy and Achievement Emotions as Mediators between Learning Climate and Learning Persistence in College Calculus: A Sequential Mediation Analysis. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2021, 92, 102094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.J.; Nejad, H.G.; Colmar, S.; Liem, G.A.D. Adaptability: How students’ responses to uncertainty and novelty predict their academic and non-academic outcomes. J. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 105, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, R.J.; Martin, A.J. Students’ adaptability in mathematics: Examining self-reports and teachers’ report and links with engagement and achievement outcomes. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 49, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rooij, E.C.; Jansen, E.P.; van de Grift, W.J. First-year university students’ academic success: The importance of academic adjustment. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2018, 33, 749–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, D.J. Motivational factors, learning strategies and resource management as predictors of course grades. Coll. Stud. J. 2006, 40, 423–429. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, M.; Abraham, C.; Bond, R. Psychological correlates of university students’ academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 138, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinko, M.J.; Mackey, J.D. Attribution Theory: An Introduction to the Special Issue. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychol. Rev. 1985, 92, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, T.L.; Daniels, L.M.; Stupnisky, R.H.; Perry, R.P.; Hladkyj, S. The effect of attributional retraining on mastery and performance motivation among first-year college students. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 30, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azemi, K.; Garavand, Y.; Arabzadeh, M. The Effect of Attributional Retraining Program on Learned Helplessness and Achievement Motivation in Students with Low Academic Achievement in Middle School. Q. J. Soc. Work. 2021, 9, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Boese, G.D.; Stewart, T.L.; Perry, R.P.; Hamm, J.M. Assisting failure-prone individuals to navigate achievement transitions using a cognitive motivation treatment (attributional retraining). J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 43, 1946–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamm, J.M.; Perry, R.P.; Clifton, R.A.; Chipperfield, J.G.; Boese, G.D. Attributional retraining: A motivation treatment with differential psychosocial and performance benefits for failure-prone individuals in competitive achievement settings. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 36, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity 2003, 2, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, M.E.; Schallert, D.L.; Mohammed, S.S.; Roberts, R.M.; Chen, Y.J. Self-kindness when facing stress: The role of self-compassion, goal regulation, and support in college students’ well-being. Motiv. Emot. 2009, 33, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D.; Hsieh, Y.P.; Dejitterat, K. Self-compassion, achievement goals, and coping with academic failure. Self Identity 2005, 4, 263–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.D.; Kennett, D.J.; Hopewell, N.M. Examining the importance of academic-specific self-compassion in the academic self-control model. J. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 159, 676–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D.; Kirkpatrick, K.L.; Rude, S.S. Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. J. Res. Pers. 2007, 41, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.L.; Astin, J.A.; Bishop, S.R.; Cordova, M. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for health care professionals: Results from a randomized trial. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2005, 12, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Education Statistics. U.S. Education: During the Pandemic and Beyond; National Center for Education Statistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/annualreports/pdf/Education-Covid-time.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Cameron, M.; Lacy, T.A.; Siegel, P.; Wu, J.; Wilson, A.; Johnson, R.; Burns, R.; Wine, J. 2019–20 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS:20): First Look at the Impact of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic on Undergraduate Student Enrollment, Housing, and Finances (Preliminary Data) (NCES 2021-456). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. 2021. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2021/2021456.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Anwar, A.; Barut, A.; Pala, F.; Kilinc-Ata, N.; Kaya, E.; Lien, D.T.Q. A Different Look at the Environmental Kuznets Curve from the Perspective of Environmental Deterioration and Economic Policy Uncertainty: Evidence from Fragile Countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collazos, N.E.; Obregón, T.A.M.; Pepicano, M.A.C.; Mosquera, F.E.C. Estilos de Vida en Estudiantes Universitarios de un Programa Académico de Salud. Enferm. Investig. 2021, 6, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, T.; Kroner, U.; Romer, R.L.; Rösel, D. From a Bipartite Gondwanan Shelf to an Arcuate Variscan Belt: The Early Paleozoic Evolution of Northern Peri-Gondwana. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2019, 192, 491–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Yu, Z. Exploring the Effects of Achievement Emotions on Online Learning Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 977931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirrone, C.; Varrasi, S.; Platania, G.A.; Castellano, S. Face-to-Face and Online Learning: The Role of Technology in Students’ Metacognition. CEUR Workshop Proc. 2021, 2817. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, P.J. Difference in Higher Education Pedagogies: Gender, Emotion, and Shame. Gend. Educ. 2017, 29, 430–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.E.; Waugh, R.M. A dynamical systems perspective regarding students’ learning processes: Shame reactions and emergent self-organizations. In Emotion in Education; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 125–145. [Google Scholar]

- Shell, D.F.; Brooks, D.W.; Trainin, G.; Wilson, K.M.; Kauffman, D.F.; Herr, L.M.T. The Unified Learning Model: How Motivational, Cognitive, and Neurobiological Sciences Inform Best Teaching Practices; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).