Impact of Affective and Cognitive Variables on University Student Reading Comprehension

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Impact of Psychological Variables on Reading Comprehension

1.2. Linguistic Variables in Text Comprehension

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

- ▪

- Tasks for the measurement of reading comprehension

- ▪

- Tasks for the measurement of language skills

- ▪

- Tasks for the measurement of cognitive abilities

- ▪

- Tasks for the measurement of motivation towards reading

2.3. Procedure

3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Data Analysis

4.2. Demographic Variables and Their Relation with the Variables of This Study

4.2.1. Relation with Age

4.2.2. Sex

4.2.3. Study Programs

4.2.4. Study Program vs. Sex

4.3. Bivariate Analyses

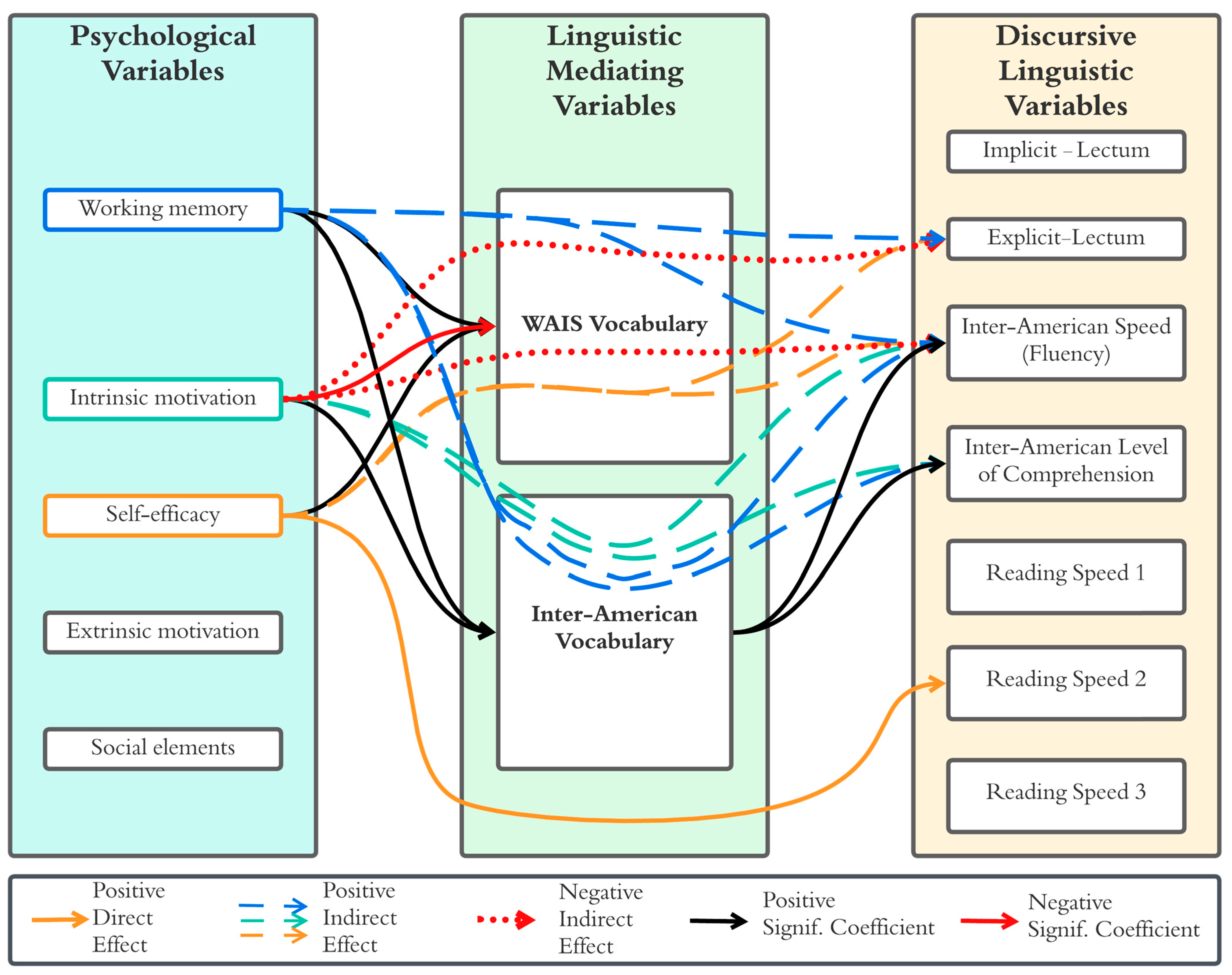

4.4. Analysis of the Mediation Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Teaching-Program Students Have Reading Comprehension Problems

5.2. Cognitive and Affective Variables Related to Demographic Differences

5.3. The Role of Vocabulary as a Mediating Variable in Reading Comprehension

5.4. The Role of Working Memory in Reading Comprehension

5.5. Motivation and Reading

5.6. Vocabulary and Reading Motivation

5.7. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McGeown, S.; Duncan, L.; Griffiths, Y.; Stohard, S. Exploring the relationship between adolescent’s reading skills, reading motivation and reading habits. Read. Writ. 2015, 28, 545–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B. Using Reading Times and Eye-Movements to Measure Cognitive Engagement. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 50, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, E.; García, R.; Rosales, J. La lectura en el aula: Qué se hace, qué se debe hacer y qué se puede hacer. Graó 2010, 16, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provasnik, S. National Center for Education Statistics. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2018/2018122.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Centro de Estudios MINEDUC. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12365/18773 (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- OCDE iLibrary. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/pisa-2018-results-volume-i_5f07c754-en (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Arroyo, C.; Valenzuela, A. Comisión Nacional de Productividad. Available online: https://cnep.cl/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Nota-Técnica-5-PIACC.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Agencia de Calidad de la Educación. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/archivos.agenciaeducacion.cl/Simce+2022+Informe+Resultados+Educativos+tomo+I.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Perfetti, C. Reading Ability; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985; ISBN 978-0195035018. [Google Scholar]

- Just, M.A.; Carpenter, P. A capacity theory of comprehension: Individual differences in working memory. Psychol. Rev. 1992, 98, 122–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, R.; Cho, B.; Hutchison, A. Cognitive Processing and Reading Comprehension. In Handbook Individual Differences in Reading; Afflerbach, P., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 364–376. ISBN 978-0-415-65887-4. [Google Scholar]

- McNamara, D.S. If Integration is the Keystone of Comprehension: Inference is the Key. Discourse Process. 2021, 58, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, C.; Gutiérrez de Blume, A.P.; Jacovina, M.; McNamara, D.; Benson, N.; Riffo, B.; Kruk, R. Reading comprehension and metacognition: The importance of inferential skills. Cogent Educ. 2019, 6, 1565067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Valcke, M.; Van Keer, H. Factors associated with reading comprehension of secondary school students. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2019, 19, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- van Moort, M.L.; Jolles, D.D.; Koornneef, A.; van den Broek, P. What you read versus what you know: Neural correlates of accessing context information and background knowledge in constructing a mental representation during reading. J. Exp. Psycho. Gen. 2020, 149, 2084–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locher, F.; Pfost, M. The relation between time spent reading and reading comprehension throughout the life course. J. Res. Read 2020, 43, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, T.; Kintsch, W. Strategies of Discourse Comprehension; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983; ISBN 978-012-712-050-8. [Google Scholar]

- Graesser, A.C. An introduction to strategic reading comprehension. In Reading Comprehension Strategies: Theories, Interventions, and Technologies; Mcnamara, D., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-1-4106-1666-1. [Google Scholar]

- Afflerbach, P.; Pearson, D.; Paris, S. Clarifying differences between reading skills and reading strategies. Read. Teach. 2008, 5, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neira Martínez, A.C.; Reyes Reyes, F.T.; Riffo Ocares, B.E. Experiencia académica y estrategias de comprensión lectora en estudiantes universitarios de primer año. Lit. Lingüística 2015, 31, 221–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parodi, G. Comprensión de Textos Escritos; Eudeba: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2005; ISBN 9789502323770. [Google Scholar]

- Elleman, A.M.; Oslund, E.L.; Griffin, N.M.; Myers, K.E. A review of middle school vocabulary interventions: Five research-based recommendations for practice. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 2019, 50, 477–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cartwright, K.B.; Lee, S.A.; Taboada Barber, A.; DeWyngaert, L.U.; Lane, A.B.; Singleton, T. Contributions of executive function and cognitive intrinsic motivation to university students’ reading comprehension. Read. Res. Q. 2020, 55, 345–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comley, J.G. Metacognition, Cognitive, Strategy Instruction, and Reading in Adult Literacy. In Review of Adult Learning and Literacy; Comings, J., Garner, B., Smith, C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 9781003417958. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, H. Online metacognitive strategies, hypermedia annotations, and motivation on hypertext comprehension. J. Educ. Tech. Soc. 2016, 19, 321–334. [Google Scholar]

- Forzani, E.; Leu, D.; Li, E.; Rhoads, C. Characteristics and Validity of an Instrument for Assessing Motivations for Online Reading to Learn. Read. Res. Q. 2021, 56, 761–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graesser, A.C.; Singer, M.; Trabasso, T. Constructing inferences during narrative text comprehension. Psychol. Rev. 1994, 3, 371–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamara, D.S. SERT: Self-explanation reading training. Discourse Proc. 2004, 38, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendeou, P.; Van den Broek, P.; Helder, A.; Karlsson, J.A. Cognitive View of Reading Comprehension: Implications for Reading Difficulties. Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 2014, 29, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwaan, R.; Magliano, J.P.; Graesser, A.C. Dimensions of situation model construction in narrative comprehension. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 1995, 21, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Laird, P.N. Mental Models: Towards a Cognitive Science of Language, Inference, and Consciousness; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Zwaan, R.; Langston, M.; Graesser, A. The construction of situation models in narrative comprehension: An event-indexing model. Psychol. Sci. 1995, 6, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsalou, L.W. Perceptual symbol systems. Behav. Brain Sci. 1999, 22, 577–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwaan, R. The inmersed experiencer: Toward an embodied theory of language comprehension. Psychol. Learn. Motiv. 2003, 44, 35–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Koestner, R.; Ryan, R.M. A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 627–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guthrie, J.T.; Wigfield, A. How motivation fits into a science of reading. Sci. Stud. Read. 1999, 3, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anmarkrud, Ø.; Bråten, I. Motivation for reading comprehension. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2009, 19, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troyer, M.; Kim, J.S.; Hale, E.; Wantchekon, K.A.; Armstrong, C. Relations among intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation, reading amount, and comprehension: A conceptual replication. Read. Writ. 2019, 32, 1197–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, K.B.; Marshall, T.R.; Huemer, C.M.; Payne, J.B. Cognitive flexibility supports reading fluency for typical readers and teacher-identified low-achieving readers. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2019, 88, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calloway, R.C.; Helder, A.; Perfetti, C.A. A measure of individual differences in readers’ approaches to text and its relation to reading experience and reading comprehension. Behav. Res. Methods 2023, 55, 899–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, S.; Medford, E.; Hughes, N. The importance of intrinsic motivation for high and low ability reader’s: Reading comprehension performance. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2011, 21, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffner, E.; Philipp, M.; Schiefele, U. Reciprocal effects between intrinsic Reading motivation and Reading competence? A cross-lagged panel model for academic track and nonacademic track students. J. Res. Read. 2016, 39, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, R.; Brâten, I. Examining the prediction of reading comprehension on different multiple-choice tests. J. Res. Read. 2010, 33, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrutia, M.; García, J. Evaluación de la comprensión lectora en alumnos de primer y tercer curso en Tenerife. Paideia 2013, 53, 73–96. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, C.; Malycha, C.P.; Schafmann, E. The influence of intrinsic motivation and synergistic extrinsic motivators on creativity and innovation. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebbecker, K.; Förster, N.; Souvignier, E. Reciprocal effects between reading achievement and intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation. Sci. Stud. Read. 2019, 23, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, A.; Pfost, M.; Artelt, C. The relationship between intrinsic motivation and reading comprehension: Mediating effects of reading amount and metacognitive knowledge of strategy use. Sci. Stud. Read. 2019, 23, 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, Y. The relationship between extrinsic motivation, home literacy, classroom instructional practices and Reading proficiency in second-grade chinese children. Res. Educ. 2018, 80, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinton, V. Examing associations between reading motivation and inference generation beyond reading comprehension skill. Read. Psychol. 2015, 36, 473–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, J.A. ¿Por qué las personas no comprenden lo que leen? (2004). Rev. Nebrija De Lingüística Apl. A La Enseñanza De Leng. 2010, 4, 124–142. Available online: https://revistas.nebrija.com/revista-linguistica/article/view/136 (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Kintsch, W.; Van Dijk, T. Toward a Model of Text Comprehension and Production. Psichol. Rev. 1978, 85, 363–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moopelwa, Y.; Condy, J. Strategies for teaching inference comprehension skills to a Grade 8 learner who lacked motivation to read. Per Linguam A J. Lang. Learn. 2019, 35, 1–15. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-1d41837ab9 (accessed on 8 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Kintsch, W. Comprehension: A paradigm for Cognition; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; ISBN 0-521-58360-8. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, P.; Mirake, A. Models of Working Memory: An Introduction. In Models Of Working Memory; Miyake, A., Shah, P., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-052-158-325-1. [Google Scholar]

- Barth, A.E.; Barnes, M.; Francis, D.; Vaughn, S.; York, M. Inferential processing among adequate and struggling adolescent comprehenders and relations to reading comprehension. Read. Writ. 2015, 28, 587–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohn-Gettler, C.M.; Kendeou, P. The interplay of reader goals, working memory, and text structure during reading. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 39, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergül, M.; Alatan, A. Depth is all you Need: Single-Stage Weakly Supervised Semantic Segmentation from Image-Level Supervision. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP) Conference, Bordeaux, France, 16 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nouwens, S.; Groen, M.A.; Kleemans, T.; Verhoeven, L. How executive functions contribute to reading comprehension. Br. J. Educ. Psychol 2021, 91, 169–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vega, M. Introducción a La Psicología Cognitiva; Alianza: Madrid, Spain, 1984; ISBN 8420665037. [Google Scholar]

- Solé, I. Competencia Lectora y Aprendizaje. Iberoamericana 2000, 59, 43–61. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2445/59387 (accessed on 8 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Cuetos, F.; González, J.; De Vega, M. Psicología del Lenguaje; Editorial Médica Panamericana: Madrid, Spain, 2015; ISBN 978-84-9110-434-6. [Google Scholar]

- De Vega, M.; Díaz, J.M.; León, H. Procesamiento del discurso. In Psicolingüística Del Español; de Vega, M., Cuetos, F., Eds.; Trotta: Madrid, Spain, 1999; ISBN 9788481643039. [Google Scholar]

- Borovsky, A.; Elman, J.; Fernald, F. Knowing a lot for one’s age: Vocabulary skill and not ageis associated with anticipatory incremental sentence interpretation in children and adults. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2012, 112, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hintz, G.; Biemann, C. Language transfer learning for supervised lexical substitution. In Proceeding of the 54th Annual Meeting of Association for Computacional Linguistics Conference, Berlin, Germany, 7–12 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Urrutia, M. Redes semánticas en línea: Una tarea de acceso léxico a partir de un estudio experimental. RLA Rev. De Lingüística Apl. 2003, 41, 119–141. [Google Scholar]

- Echeverría, M.; Urrutia, M. Incidencia del envejecimiento en el acceso léxico. Rev. Chil. De Fonoaudiol. 2004, 5, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreiras, M.; Quiñones, I.; Hernández-Cabrera, J.A.; Duñabeitia, J.A. Orthographic coding: Brain activation for letters, symbols, and digits. Cereb. Cortex 2015, 25, 4748–4760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, R.; Mendoza, C. Metodología De La Investigación: Las Rutas Cuantitativa, Cualitativa y Mixta; Editorial McGraw-Hill Education: Ciudad de México, México, 2018; ISBN 978-1-4562-6096-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riffo Ocares, B.; Reyes Reyes, F.; Novoa Lagos, A.; Véliz de Vos, M.; Castro Yáñez, G. Competencia léxica, comprensión lectora y rendimiento académico en estudiantes de enseñanza media. Lit. Lingüística 2014, 30, 136–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, M. Relación Entre La Comprensión De Lectura y Rendimiento Académico De La Cohorte 2014 De La Facultad De Ciencias Ambientales y Agrícolas, Campus Central, De La Universidad Rafael Landívar. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Rafael Landívar, Guatemala City, Guatemala, 2015. Available online: http://recursosbiblio.url.edu.gt/tesiseortiz/2015/05/83/Castaneda-Maria.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Rosas, R.; Tenorio, M.; Pizarro, M.; Cumsille, P.; Bosch, A.; Arancibia, S.; Zapata-Sepúlveda, P. Estandarización de la Escala Wechsler de Inteligencia para Adultos: Cuarta edición en Chile. Psykhe 2014, 23, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigfield, A.; Guthrie, J.T.; Tonks, S.; Perencevich, K.C. Children’s motivation for reading: Domain specificity and instructional influences. J. Educ. Res. 2004, 97, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, N.; Urrutia, M. Diseño e implementación de un taller neurodidáctico para aumentar la motivación intrínseca hacia la lectura de estudiantes de cuarto medio a través de textos científicos. In Proceedings of the Cuarto Simposio Internacional de la Cátedra Unesco Lectura y Escritura e Inauguración de la Subsede Cátedra Unesco en la Universidad Católica del Maule, Talca, Chile, 13 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R Project for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Hayes, J.R. A new framework for understanding cognition and affect in writing. In The Science of Writing; Levy, C.M., Ransdell, S., Eds.; Routledge: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2013; ISBN 9780203811122. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, D.P. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis; Lawrence Erlbaum: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 9781136676147. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Educación–CPEIP. Resultados Nacionales. Evaluación Nacional Diagnóstica de la Formación Inicial Docente 2018. Biblioteca Digital Mineduc. Available online: https://bibliotecadigital.mineduc.cl/handle/20.500.12365/4660 (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Reeve, J. Motivación y Emoción; México. D.F. Editorial; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-607-15-0300-8. [Google Scholar]

- Wnek, K. The Relationship between Age, Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation, and How It Affects Job Satisfaction Amongst Salespeople. Master’s Thesis, National College of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland, 2019. Available online: https://norma.ncirl.ie/4011/ (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Hashiguchi, N.; Sengoku, S.; Kubota, Y.; Kitahara, S.; Lim, Y.; Kodama, K. Age-Dependent Influence of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations on Construction Worker Performance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 18, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillet, N.; Vallerand, R.; Lafrenière, M.A. Intrinsic and extrinsic school motivation as a function of age: The mediating role of autonomy support. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2012, 15, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, J. Comprensión Lectora Y Memoria Operativa: Aspectos Evolutivos e Instruccionales; Paidos Ibérica: Barcelona, Spain, 2004; ISBN 9788449316876. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, M.; Decker, E. The current state of motivation to read among middle school students. Read. Psychol. 2009, 30, 466–485. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1080/02702710902733535 (accessed on 8 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Alloway, T.; Alloway, R. Investigating the predictive roles of working memory and IQ in academic attainment. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2010, 106, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, L.; Wigfield, A. Dimensions of children’s motivation for Reading and their relations to Reading activity and Reading achievement. Read. Res. Q. 1999, 34, 452–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J.; Wigfield, A.; Harold, R.; Blumendfeld, P. Age and gender differences in children’s self and task perceptions during elementary school. Child Dev. 1993, 64, 830–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núñez, J.; Martín-Albo, J.; Navarro, J.; Grijalvo, F. Validación de la escala de motivación educativa (EME) en Paraguay. Rev. Inter. De Psicol. 2006, 40, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, S.; Gallego, J. Relación entre vocabulario y comprensión lectora: Un estudio transversal en educación básica. Rev. Signos 2021, 54, 354–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, E.; Kronmüller, E. Adult vocabulary modulates speed of word integration into preceding text across sentence boundaries: Evidence from self-paced reading. Read. Res. Q. 2020, 55, 663–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feller, D.P.; Talwar, A.; Greenberg, D.; Kopatich, R.D.; Magliano, J.P. Exploring moderational and mediational relations among word reading, vocabulary, sentence processing and comprehension for struggling adult readers. J. Res. Read. 2023, 32, 1197–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.H.; Tremblay, K.A.; Binder, K.S. The factor structure of vocabulary: An investigation of breadth and depth of adults with low literacy skills. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 2020, 49, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tighe, E.L.; Reed, D.K.; Kaldes, G.; Talwar, A.; Doan, C.U.S. PIAAC Gateway. Available online: https://scholar.google.es/scholar?hl=es&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Examining+Individual+Differences+in+PIAAC+Literacy+Performance%3A+Reading+Components+and+Demographic+Characteristics+of+Low-Skilled+Adults+From+the+US+Prison+and+Household+Samples&btnG= (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Talwar, A.; Greenberg, D.; Tighe, E.L.; Li, H. Examining the reading-related competencies of struggling adult readers: Nuances across reading comprehension assessments and performance levels. Read. Writ. 2021, 34, 1569–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.D.; Shipstead, Z.; Harrison, T.L.; Redick, T.S.; Bunting, M.; Engle, R.W. The role of maintenance and disengagement in predicting reading comprehension and vocabulary learning. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2020, 46, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palladino, P.; Cornoldi, C.; De Beni, R.; Pazzaglia, F. Working memory and updating processes in reading comprehension. Mem. Cognit. 2001, 29, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christopher, M.E.; Miyake, A.; Keenan, J.M.; Pennington, B.; DeFries, J.C.; Wadsworth, S.J.; Willcut, E.; Olson, R.K. Predicting word reading and comprehension with executive function and speed measures across development: A latent variable analysis. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2012, 141, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruïne, A.; Jolles, D.; van den Broek, P. Minding the load or loading the mind: The effect of manipulating working memory on coherence monitoring. J. Mem. Lang. 2021, 118, 104212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freed, E.M.; Hamilton, S.T.; Long, D.L. Comprehension in proficient readers: The nature of individual variation. J. Mem. Lang 2017, 97, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Shintani, N.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y. The effectiveness of post-reading word-focused activities and their associations with working memory. System 2017, 70, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffner, E.; Schiefele, U.; Ulferts, H. Reading amount as a mediator of the effects of intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation on reading comprehension. Read. Res. Q. 2013, 48, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.W.; Sok, S.; Do, J. Role of individual differences in incidental L2 vocabulary acquisition through listening to stories: Metacognitive awareness and motivation. Inter. Rev. Appl. Linguist. Lang. Teach. 2023, 61, 1669–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Gan, Z. Reading motivation, self-regulated reading strategies and English vocabulary knowledge: Which most predicted students’ English reading comprehension. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1041870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.H.Y.; Guthrie, J.T. Modeling the effects of intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, amount of reading, and past reading achievement on text comprehension between US and Chinese students. Read. Res. Q. 2004, 39, 162–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M.; Mcelvany, N.; Kortenbruck, M. Intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation as predictors of reading literacy: A longitudinal study. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 102, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y. How motivational constructs interact to predict elementary students’ reading performance: Examples from attitudes and self-concept in reading. Learn. Indiv. Differ. 2011, 21, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avendaño Monje, M.J.; Barra Almagiá, E. Autoeficacia, apoyo social y calidad de vida en adolescentes con enfermedades crónicas. Terapia sicológica 2008, 262, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louick, R.; Leider, C.M.; Daley, S.G.; Proctor, C.P.; Gardner, G.L. Motivation for reading among struggling middle school readers: A mixed methods study. Learn. Indiv. Differ. 2016, 49, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondé, D.; Cabellos, B.; Gràcia, M.; Jiménez, V.; Alvarado, J.M. The Role of Emotional Intelligence, Meta-Comprehension Knowledge and Oral Communication on Reading Self-Concept and Reading Comprehension. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Yu, J.J.; Tong, X. Social–Emotional Skills Correlate with Reading Ability among Typically Developing Readers: A Meta-Analysis. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological variables | ||||

| Working memory—WAIS | 39.81 | 7.93 | 0.00 | 63.00 |

| Self-efficacy | 13.51 | 3.87 | 0.00 | 21.00 |

| Intrinsic motivation | 32.35 | 8.19 | 0.00 | 44.00 |

| Extrinsic motivation | 19.52 | 7.87 | 0.00 | 38.00 |

| Social elements | 17.86 | 5.85 | 0.00 | 31.00 |

| Mediating linguistics | ||||

| WAIS Vocabulary | 31.98 | 8.66 | 0.00 | 49.00 |

| Inter-American Vocabulary | 28.03 | 7.45 | 10.00 | 44.00 |

| Reading performance | ||||

| Explicit—Lectum | 9.92 | 3.09 | 2.00 | 16.00 |

| Implicit—Lectum | 13.98 | 3.83 | 4.00 | 22.00 |

| Inter-American Speed | 11.98 | 3.97 | 2.00 | 26.00 |

| Inter-American Comprehension Level | 22.73 | 6.21 | 13.00 | 38.00 |

| Reading Speed 1 | 133.60 | 39.09 | 60.34 | 241.00 |

| Reading Speed 2 | 162.80 | 45.47 | 76.86 | 295.60 |

| Reading Speed 3 | 39.17 | 9.12 | 19.92 | 59.43 |

| Variables | r | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Psychological variables | ||

| Working memory—WAIS | 0.15 | 0.26 |

| Self-efficacy | −0.18 | 0.17 |

| Intrinsic motivation | −0.10 | 0.46 |

| Extrinsic motivation | −0.48 | 0.00 |

| Social elements | −0.30 | 0.02 |

| Mediating linguistics | ||

| WAIS Vocabulary | 0.14 | 0.29 |

| Inter-American Vocabulary | 0.04 | 0.76 |

| Reading performance | ||

| Explicit—Lectum | 0.00 | 0.99 |

| Implicit—Lectum | 0.10 | 0.45 |

| Inter-American Speed | 0.22 | 0.09 |

| Inter-American Comprehension Level | 0.09 | 0.49 |

| Reading Speed 1 | 0.14 | 0.27 |

| Reading Speed 2 | 0.07 | 0.59 |

| Reading Speed 3 | 0.12 | 0.37 |

| Variables | Female | Male | Statistic | p-Value | Effect Size (d) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| Psychological variables | |||||||

| Working memory—WAIS | 38.73 | 7.29 | 48.43 | 8.08 | U = 64.50 | 0.00 | 1.32 |

| Self-efficacy | 13.48 | 3.94 | 13.71 | 3.60 | U = 183.00 | 0.78 | 0.06 |

| Intrinsic motivation | 32.00 | 8.28 | 35.14 | 7.43 | U = 147.50 | 0.29 | 0.38 |

| Extrinsic motivation | 19.57 | 7.72 | 19.14 | 9.70 | U = 213.50 | 0.71 | 0.05 |

| Social elements | 17.95 | 6.01 | 17.14 | 4.74 | U = 223.00 | 0.56 | 0.14 |

| Mediating linguistics | |||||||

| WAIS Vocabulary | 31.21 | 8.66 | 38.14 | 6.20 | U = 102.50 | 0.04 | 0.82 |

| Inter-American Vocabulary | 27.55 | 7.24 | 31.86 | 8.63 | U = 136.00 | 0.19 | 0.58 |

| Reading performance | |||||||

| Explicit—Lectum | 9.80 | 3.11 | 10.86 | 2.97 | U = 155.00 | 0.37 | 0.34 |

| Implicit—Lectum | 13.86 | 3.95 | 15.00 | 2.71 | U = 155.00 | 0.37 | 0.30 |

| Inter-American Speed | 11.93 | 4.00 | 12.43 | 3.95 | U = 166.00 | 0.52 | 0.13 |

| Inter-American Comprehension Level | 22.54 | 6.20 | 24.29 | 6.53 | U = 167.00 | 0.53 | 0.28 |

| Reading Speed 1 | 137.30 | 38.21 | 104.00 | 35.34 | U = 282.00 | 0.06 | 0.88 |

| Reading Speed 2 | 168.40 | 43.42 | 118.60 | 38.80 | U = 312.00 | 0.01 | 1.16 |

| Reading Speed 3 | 39.73 | 9.11 | 34.70 | 8.42 | U = 251.00 | 0.23 | 0.56 |

| Variables | Primary Education Teaching | Special Education | Subject Teaching | Statistic | p-Value | p-Adjust | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| Psychological variables | |||||||||

| Working memory—WAIS | 37.50 | 13.66 | 38.80 | 5.34 | 44.69 | 7.64 | X2(2) = 6.99 | 0.03 | 0.43 |

| Self-efficacy | 13.00 | 5.31 | 14.12 | 3.36 | 12.00 | 3.96 | X2(2) = 2.36 | 0.31 | 1.00 |

| Intrinsic motivation | 31.10 | 11.72 | 33.83 | 6.81 | 28.77 | 8.39 | X2(2) = 3.71 | 0.16 | 1.00 |

| Extrinsic motivation | 17.70 | 8.08 | 20.23 | 7.67 | 18.77 | 8.67 | X2(2) = 0.81 | 0.67 | 1.00 |

| Social elements | 17.80 | 7.24 | 18.27 | 5.87 | 16.61 | 4.86 | X2(2) = 1.55 | 0.46 | 1.00 |

| Mediating linguistics | |||||||||

| WAIS Vocabulary | 27.10 | 11.82 | 31.95 | 7.52 | 35.85 | 7.95 | X2(2) = 6.91 | 0.03 | 0.43 |

| Inter-American Vocabulary | 24.20 | 8.59 | 27.75 | 6.91 | 31.85 | 6.94 | X2(2) = 5.54 | 0.06 | 0.75 |

| Reading performance | |||||||||

| Explicit—Lectum | 8.80 | 2.44 | 9.78 | 3.27 | 11.23 | 2.65 | X2(2) = 4.00 | 0.14 | 1.00 |

| Implicit—Lectum | 12.70 | 3.89 | 13.88 | 3.90 | 15.31 | 3.45 | X2(2) = 3.47 | 0.18 | 1.00 |

| Inter-American Speed | 12.20 | 6.03 | 11.55 | 3.29 | 13.15 | 4.08 | X2(2) = 2.57 | 0.28 | 1.00 |

| Inter-American Comprehension Level | 20.20 | 4.05 | 22.77 | 6.39 | 24.54 | 6.72 | X2(2) = 2.48 | 0.29 | 1.00 |

| Reading Speed 1 | 124.50 | 31.87 | 139.00 | 38.79 | 124.10 | 44.50 | X2(2) = 1.84 | 0.40 | 1.00 |

| Reading Speed 2 | 158.50 | 32.33 | 170.70 | 44.72 | 142.10 | 52.08 | X2(2) = 3.28 | 0.19 | 1.00 |

| Reading Speed 3 | 39.03 | 12.40 | 39.98 | 8.58 | 36.82 | 8.16 | X2(2) = 1.09 | 0.58 | 1.00 |

| Psychological Variables | Linguistic Mediating Variables | Discursive Linguistic Variables | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic Motivation | Self-Efficacy | Extrinsic Motivation | Social Elements | WAIS Vocabulary | Inter. Vocabulary | Implicit Lectum | Explicit Lectum | Inter. Speed | Inter. Level Comp. | Reading Speed 1 | Reading Speed 2 | Reading Speed 3 | ||||||||||||||

| Working Memory | −0.11 | −0.13 | 0.07 | −0.14 | 0.59 | ** | 0.38 | ** | 0.28 | * | 0.22 | 0.37 | ** | 0.33 | ** | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.21 | ||||||||

| Intrinsic Motivation | 1 | ** | 0.80 | ** | 0.36 | ** | 0.69 | ** | −0.12 | 0.14 | 0.07 | −0.01 | −0.16 | −0.06 | 0.16 | 0.24 | 0.04 | |||||||||

| Self-Efficacy | 1 | ** | 0.36 | ** | 0.69 | ** | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.07 | −0.15 | −0.02 | 0.22 | 0.32 | * | 0.03 | ||||||||||

| Extrinsic Motivation | 1 | ** | 0.58 | ** | 0.13 | 0.05 | −0.15 | 0.18 | −0.14 | −0.14 | −0.12 | −0.01 | −0.12 | |||||||||||||

| Social Elements | 1 | ** | −0.08 | 0.03 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.11 | −0.17 | 0.00 | 0.08 | −0.17 | |||||||||||||||

| WAIS Vocabulary | 1 | ** | 0.28 | * | 0.29 | * | 0.39 | ** | 0.42 | ** | 0.30 | * | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.01 | |||||||||||

| Inter. Vocabulary | 1 | ** | 0.26 | * | 0.27 | * | 0.51 | ** | 0.53 | ** | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.15 | |||||||||||||

| Implicit Lectum | 1 | ** | 0.52 | ** | 0.30 | * | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.08 | ||||||||||||||||

| Explicit Lectum | 1 | ** | 0.10 | 0.10 | −0.04 | −0.06 | −0.02 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Inter. Speed | 1 | ** | 0.54 | ** | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.33 | ** | ||||||||||||||||||

| Inter. Level Comp. | 1 | ** | 0.40 | ** | 0.37 | ** | 0.30 | * | ||||||||||||||||||

| Reading Speed 1 | 1 | ** | 0.94 | ** | 0.61 | ** | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Reading Speed 2 | 1 | ** | 0.62 | ** | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reading Speed 3 | 1 | ** | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Urrutia, M.; Mariángel, S.; Pino, E.J.; Guevara, P.; Torres-Ocampo, K.; Troncoso-Seguel, M.; Bustos, C.; Marrero, H. Impact of Affective and Cognitive Variables on University Student Reading Comprehension. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 554. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060554

Urrutia M, Mariángel S, Pino EJ, Guevara P, Torres-Ocampo K, Troncoso-Seguel M, Bustos C, Marrero H. Impact of Affective and Cognitive Variables on University Student Reading Comprehension. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(6):554. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060554

Chicago/Turabian StyleUrrutia, Mabel, Sandra Mariángel, Esteban J. Pino, Pamela Guevara, Karina Torres-Ocampo, Maria Troncoso-Seguel, Claudio Bustos, and Hipólito Marrero. 2024. "Impact of Affective and Cognitive Variables on University Student Reading Comprehension" Education Sciences 14, no. 6: 554. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060554

APA StyleUrrutia, M., Mariángel, S., Pino, E. J., Guevara, P., Torres-Ocampo, K., Troncoso-Seguel, M., Bustos, C., & Marrero, H. (2024). Impact of Affective and Cognitive Variables on University Student Reading Comprehension. Education Sciences, 14(6), 554. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060554