“Otherwise, There Would Be No Point in Going to School”: Children’s Views on Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Assessment in Primary School: Theoretical Frame and State of the Art

2.1. The International Perspective

2.2. The Italian School System and Assessment at the Primary School

2.3. Childhood Studies

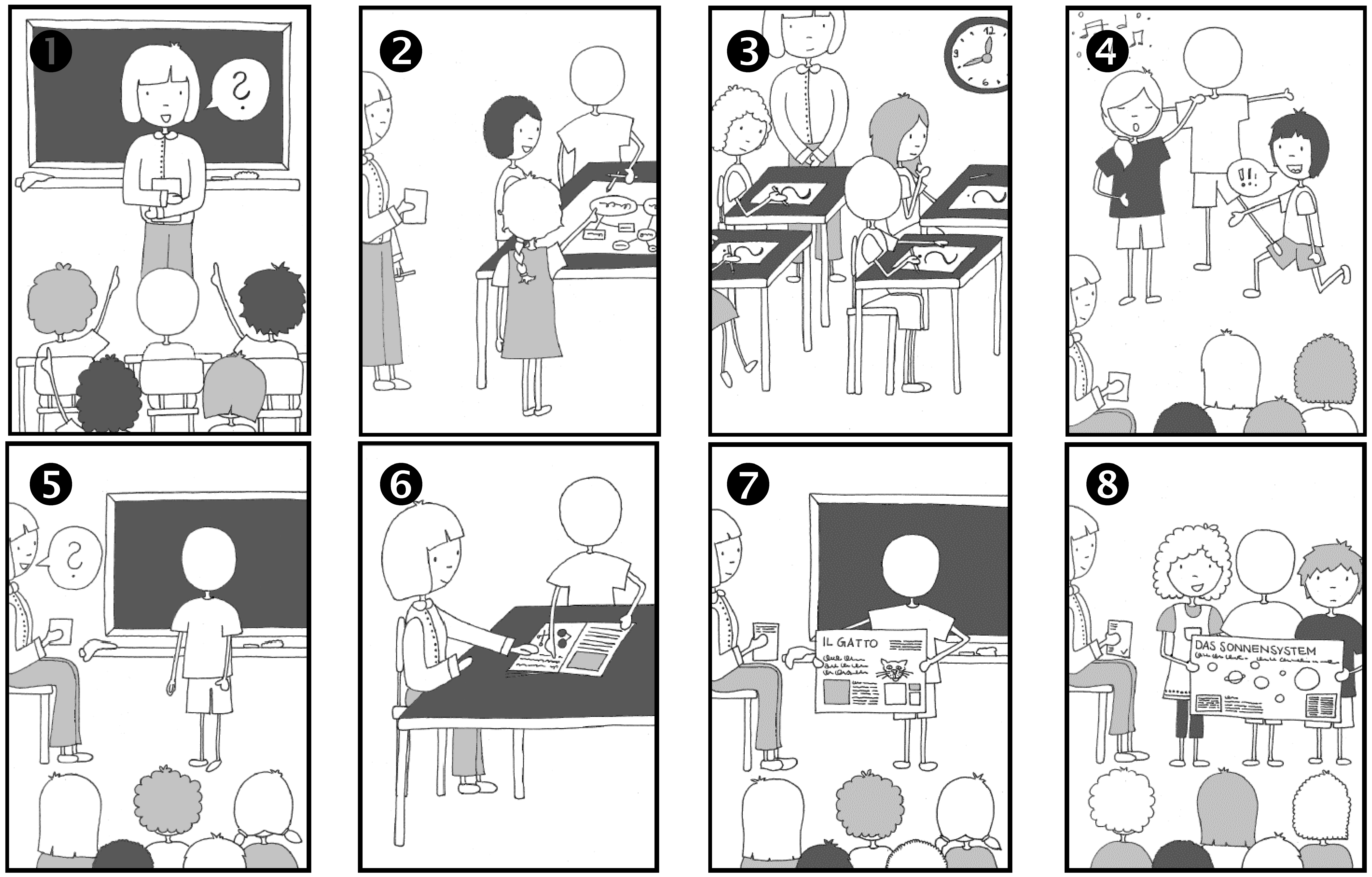

3. Methodological Design: Children’s Voices on Assessment

- What are children’s perceptions of assessment practices and results? What factors affect these perceptions?

- How do assessment practices contribute to generating power relations in inclusive schools? How do children deal with them?

- How do assessment practices contribute to shaping classroom differences in inclusive primary schools?

- How do the new Italian descriptive standards translate into specific social practices, and how do children perceive them?

- What implications can be highlighted for teacher education in this context?

4. Children’s Views on Assessment

4.1. Findings

4.2. Children’s Perceptions of Assessment—The Case of Alice

Interviewer: […] How do your teachers know if you have learnt anything?Alice: Because I often raise my hand, uhm, then they understand that I … being a child … because I am also a bit shy.Interviewer: AhhAlice: However, because I know them, and-and I confide in them, I often raise my hand because they put things into my head well.[…]Interviewer: M-m (nodding), and do you talk to them about your learning?Alice: Actually, I discuss a lot with my teachers because, if mum is not present, it is like they are, ehm… my babysitters.Interviewer: M-m (nodding)Alice: Because they make me learn, eh… kind of, like mum.(Daffodil_transcript_16, Pos. 39–42; 47–50)

Interviewer: How do you use it? [Feedback]Alice: I use it either when I do something wrong, which I then learn, because, um … I, when I am told that something is wrong, I, I agree, because I am not the teacher, I am a child, a pupil trying to learn, and so I let them, I let them tell me when I make mistakes.(Daffodil_transcript_16, Pos. 159–160)

Interviewer: […] Why do you think teachers give you feedback?Alice: Because to me, children have to learn, yes, and in my opinion, they [the teachers] do those activities for … for … […], to make children try to, to learn because not everything we do is right… To put this into our headsInterviewer: M-m (nodding)Alice: Eh, and yet, when we try hard, things are often correct. When we try to study our best, we can do the tests, uhm, or when we do not try to commit ourselves.Interviewer: M-m (nodding)Alice: So, it is natural that the teachers perceive that we do not commit or do commit.(Daffodil_transcript_16, Pos. 167–174)

Alice: […] if they see that in those two days, in that week we have committed to homework or studying, mm, they go for a test.Interviewer: Okay.Alice: However, this is not out of malice […] but because they see that we have not committed ourselves.(Daffodil_transcript_16, Pos. 180–184)

Interviewer: […] What if you were a teacher? What would you do to understand if your pupils have learnt?Alice: So, I … I do not want to be a mean teacher because the pupils might get hurt. However, I do not want to be too good either, because then you get to the point that you never do written exams. You never do oral exams. I want to be a regular teacher who, when needed, does oral exams, when it becomes more necessary does written exams.(Daffodil_transcript_16, Pos. 185–186)

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Limitations

5.2. Discussion

5.3. Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Black, P.; Harrison, C.; Lee, C.; Marshall, B.; Wiliam, D. Working inside the Black Box: Assessment for Learning in the Classroom; King’s College London: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Laveault, D.; Allal, L. Assessment for Learning: Meeting the Challange of Implementation; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA; Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, F.T. Persistent Inequality in Educational Attainment and Its Institutional Context. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2008, 24, 543–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buch, S.; Sparfeldt, J. Diagnostik, Beurteilung und Förderung als Gegenstand der Lehrerinnen- und Lehrerbildung. In Handbuch Lehrerinnen- und Lehrerbildung; Cramer, C., König, J., Rothland, M., Blömeke, S., Eds.; Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2020; pp. 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, N.-C.; Zala-Mezö, E.; Herzig, P.; Häbig, J.; Müller-Kuhn, D. Partizipation von Schülerinnen und Schülern ermöglichen: Perspektiven von Lehrpersonen. J. Schulentwickl. 2017, 4, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Oevermann, U. Theoretische Skizze einer revidierten Theorie professionalisierten Handelns. In Pädagogische Professionalität—Untersuchungen zum Typus Pädagogischen Handelns; Helsper, W., Combe, A., Eds.; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt a.M., Germany, 1996; pp. 70–182. [Google Scholar]

- Helsper, W. Professionalität und Professionalisierung Pädagogischen Handelns: Eine Einführung; Barbara Budrich: Opladen, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Meseth, W.; Proske, M.; Radtke, F.-O. Kontrolliertes Laissez-faire. Auf dem Weg zu einer kontingenzgewärtigen Unterrichtstheorie. ZfPäd 2012, 58, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paseka, A.; Keller-Schneider, M.; Combe, A. Ungewissheit als Herausforderung für Pädagogisches Handeln; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Edgerton, J.D.; Roberts, L.W.; Peter, T. Disparities in Academic Achievement: Assessing the Role of Habitus and Practice. Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 114, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, R.-T. “Habitus” und “kulturelle Passung”. In Pierre Bourdieu: Pädagogische Lektüren; Rieger-Ladich, M., Grabau, C., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017; pp. 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, S.; Finnern, N.-K.; Korff, N.; Scheidt, K. Inklusiv Gleich Gerecht? Inklusion und Bildungsgerechtigkeit; Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Seitz, S.; Auer, P.; Bellacicco, R. International Perspectives on Inclusive Education—In the Light of Educational Justice; Budrich: Opladen, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. 17 Goals to Transform Our World. 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Sturm, T. Inklusion: Kritik und Herausforderung des schulischen Leistungsprinzips. Erziehungswissenschaft 2015, 26, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prengel, A. “Schlechte Leistungen”? Ethische und wissenschaftliche Kritik an schulischen Entwertungen. Sch. Inklusiv 2021, 10, 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Seitz, S. Dimensionen inklusiver Didaktik—Personalität, Sozialität und Komplexität. Z. Inkl. 2020, 15. Available online: https://www.inklusion-online.net/index.php/inklusion-online/article/view/570 (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Seitz, S.; Pfahl, L.; Steinhaus, F.; Rastede, M.; Lassek, M. Hochbegabung Inklusive. Inklusion als Impuls für Begabungsförderung an Schulen; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, T.R.; Brighton, C.M.; Tomlinson, C.A. Using Differentiated Classroom Assessment to Enhance Student Learning; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Peacock, A. Assessment for Learning without Limits; McGraw-Hill: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Imperio, A.; Seitz, S. Positioning of Children in Research on Assessment Practices in Primary School. In International Perspectives on Inclusive Education—In the Light of Educational Justice; Seitz, S., Auer, P., Bellacicco, R., Eds.; Barbara Budrich: Leverkusen, Germany, 2023; pp. 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Il Ministro dell’Istruzione. Valutazione Periodica e Finale degli Apprendimenti delle Alunne e degli Alunni delle Classi della Scuola Primaria; Ordinanza Ministeriale 172. Italy. 2020. Available online: https://www.istruzione.it/valutazione-scuola-primaria/allegati/ordinanza-172_4-12-2020.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests and Identities; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. PISA 2018 Results (Volume II): Where All Students Can Succeed; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brügelmann, H. Sind Noten Nützlich und Nötig? Ziffernzensuren und Ihre Alternativen im Empirischen Vergleich. Eine Wissenschaftliche Expertise des Grundschulverbandes, 3rd ed.; Grundschulverband: Frankfurt, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Laveault, D. Assessment Policy Enactment in Education Systems: A Few Reasons to Be Optimistic. In Assessment for Learning: Meeting the Challange of Implementation; Laveault, D., Allal, L., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA; Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Earl, L.M. Assessment as Learning: Using Classroom Assessment to Maximise Student Learning; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gomolla, M. Leistungsbeurteilung in der Schule: Zwischen Selektion und Förderung, Gerechtigkeitsanspruch und Diskriminierung. In Migration und Schulischer Wandel: Leistungs-Beurteilung; Fürstenau, S., Gomolla, M., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2012; pp. 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ingenkamp, K. Die Fragwürdigkeit der Zensurengebung; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Zielinski, W. Die Beurteilung von Schülerleistungen. In Funk Kolleg Pädagogische Psychologie; Weinert, F.E., Ed.; Fischer: Frankfurt, Germany, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Maaz, V.K.; Baeriswyl, F.; Trautwein, U. Herkunft Zensiert? Leistungsdiagnostik und Soziale Ungleichheiten in der Schule. Eine Studie im Auftrag der Vodafone Stiftung Deutschland; Vodafone Stiftung: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P.; Passeron, J.-C. Die Illusion der Chancengleichheit: Untersuchungen zur Soziologie des Bildungswesens am Beispiel Frankreichs; Klett: Stuttgart, Germany, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Helsper, W.; Kramer, R.T.; Thiersch, S. Schülerhabitus. Theoretische und Empirische Analysen zum Bourdieuschen Theorem der kulturellen Passung; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, R.-T.; Helsper, W. Kulturelle Passung und Bildungsungleichheit—Potentiale einer an Bourdieu Orientierten Analyse der Bildungsungleichheit. In Bildungsungleichheit Revisited. Bildung und Soziale Ungleichheit vom Kindergarten bis zur Hochschule; Krüger, H.-H., Rabe-Kleberg, U., Kramer, R.-T., Budde, J., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2010; pp. 103–125. [Google Scholar]

- Martiny, S.; Götz, T. Stereotype Threat in Lern- und Leistungssituationen: Theoretische Ansätze, empirische Befunde und praktische Implikationen. In Motivation, Selbstregulation und Leistungsexzellenz; Markus, D., Ed.; LIT-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2011; pp. 153–178. [Google Scholar]

- Ditton, H. Kontexteffekte und Bildungsungleichheit. Mechanismen und Erklärungsmuster. In Bildungskontexte. Strukturelle Voraussetzungen und Ursachen ungleicher Bildungschancen; Becker, R., Schulze, A., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2013; pp. 173–206. [Google Scholar]

- Crick, R.D. Integrating the personal with the public. Values, Virtues and Learning and the Challenges of assessment. In International Research Handbook on Values Education and Student Wellbeing; Lovat, T., Toomey, R., Clement, N., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany; London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 883–896. [Google Scholar]

- Prengel, A. Pädagogische Beziehungen Zwischen Anerkennung, Verletzung und Ambivalenz; Budrich: Opladen, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming, J.J.; Van der Kleij, F. Effective Enactment of Assessment for Learning and Student Diversity in Australia. In Assessment for Learning: Meeting the Challange of Implementation; Laveault, D., Allal, L., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA; Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Prengel, A. Individualisierung in der “Caring-Community”—Zur inklusiven Verbesserung von Lernleistungen. In Leistung Inklusive? Inklusion in der Leistungsgesellschaft; Textor, A., Grüter, S., Schiermeyer-Reichl, I., Streese, B., Eds.; Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2017; Volume 2, pp. 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sacher, W. Leistungen Entwickeln, Überprüfen und Beurteilen. Bewährte und Neue Wege für die Primar- und Sekundarstufe, 6th ed.; Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pant, H.-A. Notengebung, Leistungsprinzip und Bildungsgerechtigkeit. In Lernen ohne Noten. Alternative Konzepte der Leistungsbewertung; Beutel, S., Pant, H.-A., Eds.; Kohlhammer: Stuttgart, Germany, 2020; pp. 22–57. [Google Scholar]

- Seitz, S.; Wilke, Y. “Dann hab’ ich das einfach gemacht”—Leistungsbeurteilung im inklusiven Unterricht der Sekundarstufe I. Schule inklusiv 2021, 11, 35–36. [Google Scholar]

- Nigris, E.; Agrusti, G. Valutare per Apprendere. La Nuova Valutazione Descrittiva nella Scuola Primaria; Pearson Italia: Milano, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt-Smith, C.; Klenowski, V.; Colbert, P. Assessment Understood as Enabling. A Time to Rebalance Improvement and Accountability Goals. In Designing Assessment for Quality Learning; Wyatt-Smith, C., Klenowski, V., Colbert, P., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA; Dordrecht, The Netherlands; London, UK, 2014; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Beutel, S.I.; Pant, H.A. Lernen ohne Noten. Alternative Konzepte der Leistungsbewertung; Kohlhammer: Stuttgart, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bohl, T. Prüfen und Bewerten im Offenen Unterricht; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Seitz, S.; Häsel-Weide, U.; Wilke, Y.; Wallner, M.; Heckmann, L. Expertise von Lehrpersonen für inklusiven Mathematikunterricht der Sekundarstufe—Ausgangspunkte zur Professionalisierungsforschung. k ON Köln. Online J. Lehrer* Innenbildung 2020, 2, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istituto Nazionale Documentazione Innovazione Ricerca Educativa. Il Sistema Educativo Italiano; Indire—Ricerca per l’InnoVazione della Scuola Italiana. 2013. Available online: https://www.indire.it/lucabas/lkmw_file/eurydice/QUADERNO_per_WEB.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Pulyer, U.; Stuppner, I. Schulautonomie und Evaluation in Südtirol. In Schulautonomie—Perspektiven in Europa: Befunde aus dem EU-Projekt INNOVITAS; Rauscher, E., Wiesner, C., Paasch, D., Heißenberger, P., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2019; pp. 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Chiappetta Cajola, L. Didattica Inclusiva, Valutazione e Orientamento. ICF-CY, Portfolio e Certificazione delle Competenze degli Allievi con Disabilità; Anicia: Roma, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brugger, E. Die Integration von Kindern und Jugendlichen mit einer Behinderung in einem inklusiven Bildungssystem am Beispiel Italien—Südtirol. Z. Inkl. 2016, 11. Available online: https://www.inklusion-online.net/index.php/inklusiononline/article/view/366 (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Triventi, M. Le disuguaglianze di istruzione secondo l’origine sociale: Una rassegna della letteratura sul caso italiano. Sc. Democr. 2014, 2, 321–342. [Google Scholar]

- Agrusti, G. Approcci criteriali alla valutazione nella scuola primaria. RicercAzione 2021, 13, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuto, G. La valutazione formativa, per una didattica inclusiva. In Valutare per Apprendere. La Nuova Valutazione Descrittiva nella Scuola Primaria; Nigris, E., Agrusti, G., Eds.; Pearson Italia: Milano, Italy, 2021; pp. 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Breidenstein, G.; Thompson, C. Schulische Leistungsbewertung als Praxis der Subjektivierung. In Interferenzen: Perspektiven Kulturwissenschaftlicher Bildungsforschung; Thompson, C., Jergus, K., Breidenstein, G., Eds.; Velbrück: Weilerswist, Germany, 2014; pp. 89–109. [Google Scholar]

- Gellert, U. Heterogen oder hierarchisch? Zur Konstruktion von Leistung im Unterricht. In Unscharfe Einsätze: (Re-)Produktion von Heterogenität im Schulischen Feld; Budde, J., Ed.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2013; pp. 211–227. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, D.; Birkelbach, K. Lehrer als Gatekeeper? Eine theoriegeleitete Annäherung an Determinanten und Folgen prognostischer Lehrerurteile. In Bildungskontexte. Strukturelle Voraussetzungen und Ursachen Ungleicher Bildungschancen; Becker, R., Schulze, A., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2013; pp. 207–237. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Brown, G.T.L. Teacher assessment literacy in practice: A reconceptualization. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2016, 1, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remesal, A. Accessing Primary Pupils’ Conceptions of Daily Classroom Assessment Practices. In Students Perspectives on Assessment. What Students Can Tell Us about Assessment for Learning; McInerney, D.M., Brown, G.T.L., Liem, G.A.D., Eds.; Information Age Pub: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2009; pp. 25–51. [Google Scholar]

- Heinzel, F. Kindheit und Grundschule. In Handbuch Kindheits- und Jugendforschung, 3rd ed.; Krüger, H.-H., Grunert, C., Ludwig, K., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2022; pp. 751–780. [Google Scholar]

- Esser, F.; Baader, M.S.; Betz, T.; Hungerland, B. Reconceptualising Agency and Childhood. New Perspectives in Childhood Studies; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cook-Sather, A. Tracing the evolution of student voice in educational research. In Radical Collegiality through Student Voice. Educational Experience, Policy and Practice; Bourke, R., Loveridge, J., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melton, G.B.; Gross-Manos, D.; Ben-Arieh, A.; Yazykova, E. The nature and scope of child research: Learning about children’s lives. In The SAGE Handbook of Child Research; Melton, G.B., Ben-Arieh, A., Cashmore, J., Goodman, G.S., Worley, N.K., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2014; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butschi, C.; Hedderich, I. Kindheit und Kindheitsforschung im Wandel. In Perspektiven auf Vielfalt in der Frühen Kindheit. Mit Kindern Diversität Erforschen; Hedderich, I., Reppin, J., Butschi, C., Eds.; Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2021; pp. 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, A.; Moss, P. Listening to Young Children. The Mosaic Approach; National Children’s Bureau: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Heinzel, F. Methoden der Kindheitsforschung. Ein Überblick über Forschungszugänge zur Kindlichen Perspektive; Juventa: Weinheim/München, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schütz, S.; Böhm, E.T. Forschungsmethodische Vielfalt. Der Mosaic Approach. In Perspektiven auf Vielfalt in der frühen Kindheit. Mit Kindern Diversität erforschen; Hedderich, I., Reppin, J., Butschi, C., Eds.; Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2021; Volume 2, pp. 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, G.; Main, G. Children’s Views on Their Lives and Well-Being in 15 Countries: An Initial Report on the Children’s Worlds Survey, 2013–2014; Children’s Worlds Project: York, UK, 2015; Available online: https://isciweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/ChildrensWorlds2015-FullReport-Final.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Ainscow, M.; Messiou, K. Engaging with the views of students to promote inclusion in education. J. Educ. Chang. 2018, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuten, J. “There’s Two Sides to Every Story”. How Parents Negotiate Report Card Discourse. Lang. Arts 2007, 84, 314–324. [Google Scholar]

- Beutel, S.-I. Zeugnisse aus Kindersicht. Kommunikationskultur an der Schule und Professionalisierung der Leistungsbeurteilung; Juventa: Weinheim/München, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Grittner, F. Leistungsbewertung mit Portfolio in der Grundschule. Eine Mehrperspektivische Fallstudie aus Einer Notenfreien Sechsjährigen Grundschule; Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, E. Inquiring into children’s experiences of teacher feedback: Reconceptualising Assessment for Learning. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2013, 39, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.R.; Harnett, J.A.; Brown, G.T.L. “Drawing” Out Student Conceptions: Using Pupils’ Pictures to Examine Their Conceptions of Assessment. In Student Perspectives on Assessment: What Students Can Tell Us about Assessment for Learning; McInerney, D.M., Brown, G.T.L., Liem, G.A.D., Eds.; Information Age Pub: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2009; pp. 53–83. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, V.; Mata, L.; Santos, N.N. Assessment Conceptions and Practices: Perspectives of Primary School Teachers and Students. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 631185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C.; Lundy, L.; Emerson, L.; Kerr, K. Children’s perceptions of primary science assessment in England and Wales. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2013, 39, 585–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunner-Kreisel, C.; Kuhn, M. Children’s Perspectives: Methodological Critiques and Empirical Studies. In Children and the Good Life. New Challenges for Research on Children; Andresen, S., Diehm, I., Sander, U., Ziegler, H., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2011; Volume 4, pp. 115–118. [Google Scholar]

- Breidenstein, G.; Rademacher, S. Individualisierung und Kontrolle. Empirische Studien zum Geöffneten Unterricht in der Grundschule; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Alanen, L. Modern Childhood? Exploring the ‘Child Question’ in Sociology. Publication Series A; Research Reports 50; University of Jyvaskyla, Institute for Educational Research: Jyvaskyla, Finland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Carless, D.; Lam, R. The examined life: Perspectives of lower primary school students in Hong Kong. Educ. 3-13: Int. J. Prim. Elem. Early Years Educ. 2014, 42, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnsack, R. Rekonstruktive Sozialforschung—Einführung in Methodologie und Praxis Qualitativer Forschung, 10th ed.; Leske & Budrich: Opladen, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bohnsack, R. Documentary Method. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis; Flick, U., Ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2014; pp. 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütze, F. Biographieforschung und narratives Interview. Neue Praxis 1983, 3, 283–293. [Google Scholar]

- Nohl, A.-M. Interview und Dokumentarische Methode. Anleitungen für die Forschungspraxis; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, A.; Powell, M.; Taylor, N.; Anderson, D.; Fitzgerald, R. Ethical Research Involving Children; Innocenti Publications, UNICEF Office of Research: Florence, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, D.M. Research and Evaluation in Education and Psychology. Integrating Diversity with Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Methods, 4th ed.; SAGE Publication Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Steinke, I. Gütekriterien qualitativer Forschung. In Qualitative Forschung: Ein Handbuch; Flick, U., Kardorff, E.V., Steinke, I., Eds.; Rowohlt: Reinbek, Germany, 2017; pp. 319–331. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Sociology Press: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.L.; Corbin, J. Grounded Theory. Grundlagen Qualitativer Sozialforschung; Psychologie-Verlag-Union: Weinheim, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bohnsack, R. Praxeologische Wissenssoziologie; Barbara Budrich: Opladen, Germany; Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mannheim, K. Wissenssoziologie. In Ideologie und Utopie, 6th ed.; Mannheim, K., Ed.; Schulte-Bulmke: Frankfurt, Germany, 1978; pp. 227–267. [Google Scholar]

- Hunger, I.; Zander, B.; Zweigert, M.; Schwark, C. Impulsinterviews mit Kindern im Kindergartenalter—Praktische Entwicklung und methodologische Einordnung einer Datenerhebungsmethode. In Qualitative Forschung mit Kindern, Herausforderungen, Methoden und Konzepte; Hartnack, F., Ed.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; pp. 169–192. [Google Scholar]

- Vogl, S. Mit Kindern Interviews führen: Ein praxisorientierter Überblick. In Perspektiven auf Vielfalt in der Frühen Kindheit; Hedderich, I., Reppin, J., Burtschi, C., Eds.; Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2021; pp. 142–157. [Google Scholar]

- Eid, M.; Diener, E. Handbook of Multimethod Measurement in Psychology; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Helsper, W.; Hummrich, M. Arbeitsbündnis, Schulkultur und Milieu. Reflexionen zu Grundlagen schulischer Bildungsprozesse. In Paradoxien in der Reform der Schule. Ergebnisse Qualitativer Sozialforschung; Breidenstein, G., Schütze, F., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2008; pp. 43–73. [Google Scholar]

- Brousseau, G. Fondements et méthodes de la didactique des mathématiques. Rech. Didact. Math. 1986, 7, 33–115. Available online: https://revue-rdm.com/1986/fondements-et-methodes-de-la/ (accessed on 22 June 2023).

- Berman, G.; Hart, J.; O’Mathúna, D.; Mattellone, E.; Potts, A.; O’Kane, C.; Shusterman, J.; Tanner, T. What We Know about Ethical Research Involving Children in Humanitarian Settings: An overview of principles, the literature and case studies. In Innocenti Working Paper No. 2016-18; UNICEF Office of Research: Florence, Italy, 2016; Available online: https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/IWP_2016_18.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2023).

- Zinnecker, J. Die Schule als Hinterbühne oder Nachrichten aus dem Unterleben der Schüler. In Schüler im Schulbetrieb; Reinert, G.-B., Zinnecker, J., Eds.; Rowohlt: Reinbek, Germany, 1978; pp. 29–121. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanati, M. Lernentwicklungsgespräche und Partizipation. Rekonstruktionen zur Gesprächspraxis zwischen Lehrpersonen, Grundschülern und Eltern; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- De Boer, H.; Deckert-Peaceman, H. Kinder in der Schule. Zwischen Gleichaltrigenkultur und Schulischer Ordnung; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Heinzel, F. Der Morgenkreis—Klassenöffentlicher Unterricht Zwischen Schulischen und Peerkulturellen Herausforderungen; Pädagogische Fallanthologie, Volume 13; Barbara Budrich: Berlin, Germany; Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Häcker, T. Portfolioarbeit—Ein Konzept zur Wiedergewinnung der Leistungsbeurteilung für die Pädagogische Aufgabe der Schule. In Diagnose und Beurteilung von Schülerleistungen; Sacher, W., Winter, F., Eds.; Schneider: Baltmannsweiler, Germany, 2011; pp. 217–230. [Google Scholar]

- Noesen, M. Portfolioarbeit und Lernen—Eine Qualitative Studie in einer Inklusionsorientierten Grundschule im Kontext der Luxemburgischen Bildungsreform ORBilu: Luxembourg. 2022. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10993/53009 (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Winter, F. Lerndialog statt Noten. Neue Formen der Leistungsbeurteilung; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Heinzel, F. Das Konzept der Generationenvermittlung. In Orte und Räume der Generationenvermittlung. Zur Praxis Außerschulischen Lernens von Kindern; Wiesemann, J., Flügel, A., Brill, S., Landrock, I., Eds.; Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2020; pp. 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Seitz, S.; Kaiser, M. Zur Entwicklung leistungsfördernder Schulkulturen. In Begabungsförderung, Leistungsentwicklung, Bildungsgerechtigkeit—Für alle. Beiträge aus der Begabungsforschung; Fischer, C., Fischer-Ontrup, C., Käpnick, F., Neuber, N., Solzbacher, C., Zwitserlood, P., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2020; pp. 207–222. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seitz, S.; Imperio, A.; Auer, P. “Otherwise, There Would Be No Point in Going to School”: Children’s Views on Assessment. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 828. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13080828

Seitz S, Imperio A, Auer P. “Otherwise, There Would Be No Point in Going to School”: Children’s Views on Assessment. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(8):828. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13080828

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeitz, Simone, Alessandra Imperio, and Petra Auer. 2023. "“Otherwise, There Would Be No Point in Going to School”: Children’s Views on Assessment" Education Sciences 13, no. 8: 828. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13080828

APA StyleSeitz, S., Imperio, A., & Auer, P. (2023). “Otherwise, There Would Be No Point in Going to School”: Children’s Views on Assessment. Education Sciences, 13(8), 828. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13080828