1. Introduction

Classrooms worldwide are characterised by diversity [

1]. While some forms of diversity have increased in societies, we agree with Banks and colleagues that “students are and always have been different from each other in a variety of ways” [

2] (p. 232). Therefore, the education field has a long tradition of adapting to the different needs of students [

3,

4]. Nevertheless, creating educational systems that serve all students remains a global challenge [

5]. Too often, evidence is found that education reproduces societal structures of power that favour people from dominant groups at the expense of minoritised groups [

6]. Consequently, education fails to reach its emancipatory or liberating potential [

7]. Both international policy-makers [

8,

9] and social movements (advocating for the rights of minoritised groups) denounce this injustice and call for action. Particularly, requests are made to approach diversity in education from a recognition of social inequality as a reality while pursuing inclusion, equity, and social justice [

10,

11]. In our research, we frame this stance on approaching diversity as responsiveness to diversity [

12]:

Responsiveness to diversity in education is twofold: it is taking into account differences between people in order to create qualitative learning environments for everyone, as well as responding to discriminatory injustices that exist in society and (in)directly impact education, in order to create a more equitable world [

12].

Fostering diversity-responsive education is a responsibility of all professionals in the field since all of them have the agency to change educational structures for the better [

13]. Yet, we believe teacher educators could potentially impact systems and structural inequalities even more [

14,

15]. According to the European Commission, teacher educators are “all those who actively facilitate the (formal) learning of student teachers and teachers” [

8] (p. 8). A heterogeneous group of professionals is referred to by this definition, residing inside as well as outside of higher education institutions [

16]. In this study, we focus on teacher educators working in teacher education programmes at higher education institutions because they are responsible for preparing future teachers and, thus, directly and indirectly impact how diversity is approached in education [

15]. Inevitably, these teacher educators’ individual practices—like advocating for responsiveness to diversity in education and modelling diversity-responsive practices to the future generation of teachers—can influence the direction of the educational system as a whole and, as such, tackle structural inequalities over time.

However, the limited research on teacher educators’ diversity-responsive practices has shown that teacher educators struggle to take on this responsibility [

17]. Many feel too insecure about the topic to act adequately or perceive barriers to setting up diversity-responsive practices. Evidence-informed professional development initiatives (PDIs) specifically targeted at teacher educators could address these observations. Since we concur with scholars who acknowledge teacher educators as professionals who have good reasons for doing what they do, we take teacher educators’ practices as the starting point in designing a new PDI to foster teacher educators’ responsiveness to diversity [

18]. Such practices are situated in nature. They are constituted by both personal factors, like prior experiences or career stages, and contextual factors, like institutional policies or geographical location [

19,

20]. Therefore, we argue that designing a PDI for sustainable changes that these factors be taken into account [

21]. Particularly, a participatory design is proposed, allowing for the inclusion of teacher educators in various phases of the design process to make the PDI tailored to its users and their context [

22]. In this article, we provide insight into the design of a PDI to foster teacher educators’ responsiveness to diversity by means of such a participatory process.

1.1. Objectives of a PDI to Foster Teacher Educators’ Diversity-Responsive Practices

To shed light on teacher educators’ diversity-responsive practices, we build on a recently developed conceptual framework that resulted from a systematic literature review [

12]. The framework synthesises knowledge which, until recently, was scattered across the literature. Prior attempts for synthesis might have been complicated because of the small-scale qualitative or self-study methodology that is often used to study these practices [

23] or the use of many concepts that can be associated with responsiveness to diversity (e.g., inclusion, equity, social justice) [

24]. Furthermore, a subsequent study with practising teacher educators led to the content validation of the framework, proving its potential value [

17].

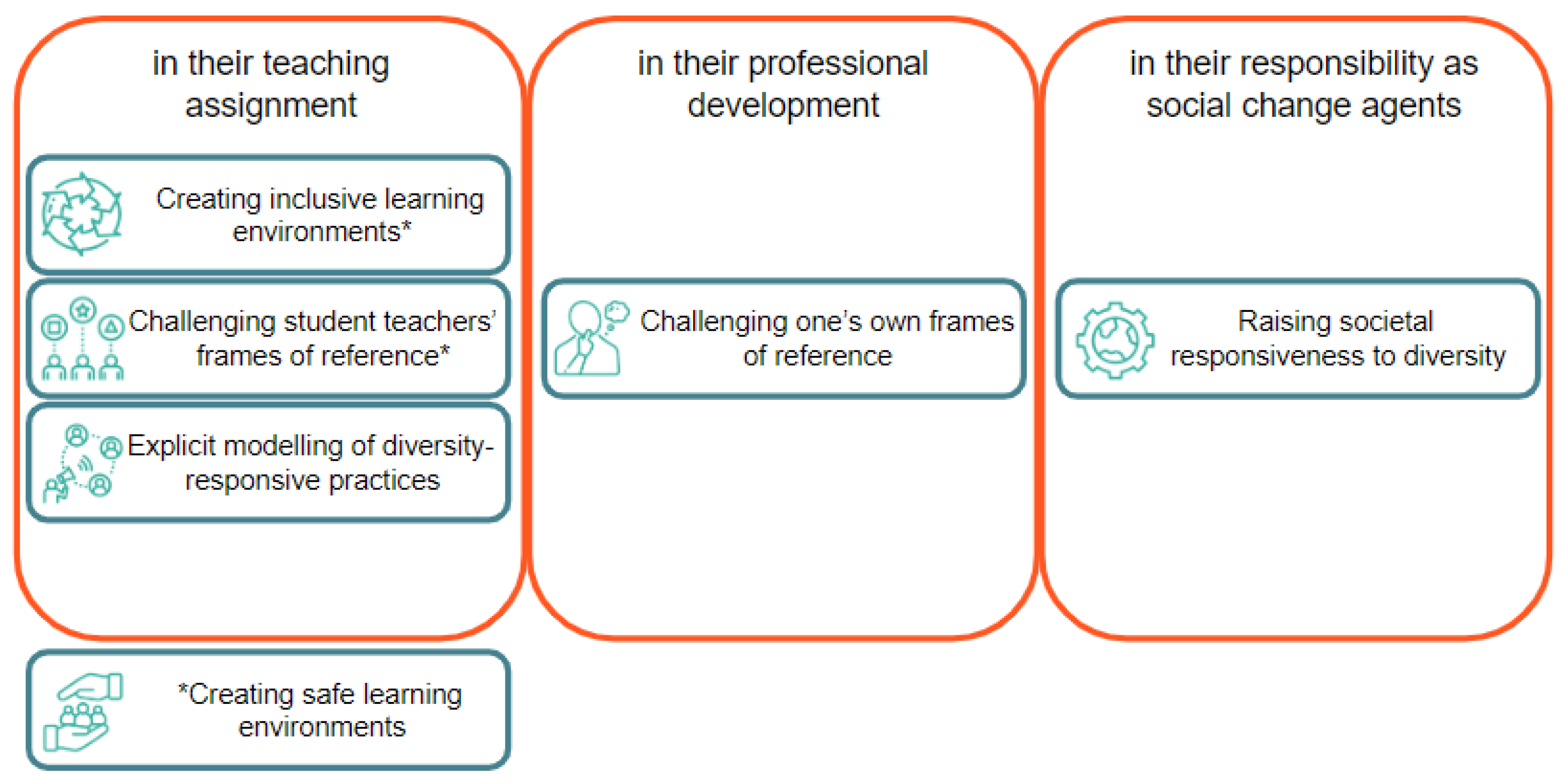

Figure 1 shows the conceptual framework of diversity-responsive practices by teacher educators.

Based on concrete practices found in the literature, the framework distinguishes five main clusters of practices that any teacher educator can implement regardless of specific teaching or other assignments. Some of these practices occur in the context of their teaching assignment or when teacher educators interact with student teachers. First, (1) creating inclusive learning environments is, like the international policy goal of inclusive education [

25], about fostering effective learning for all students [

26]. Concrete examples of this first cluster are implementing differentiated instruction or cooperative learning activities [

27]. Second, by (2) challenging student teachers’ frames of reference, teacher educators nudge student teachers to critically address what shapes their ways of thinking and to reevaluate biased self-evidences that might negatively impact their future pupils [

28]. For instance, writing reflective journals or engaging in discussions have the potential to raise student teachers’ awareness of how their own frames of reference are determined by their social position and socialisation and how some of it might perpetuate social inequalities in the world [

29,

30]. Furthermore, as a precondition to both challenging student teachers’ frames of reference and the first cluster of creating inclusive learning environments, the literature pointed towards practices about creating safe learning environments. This involves stimulating positive relationships between students as well as with students [

31]. Third, (3) explicit modelling of diversity-responsive practices concerns setting up one of the former practices while explicitly making student teachers aware of it [

32]. Teacher educators can do this by articulating the decisions they make in their teaching or by encouraging student teachers to articulate their experiences [

33]. Next, within their professional development, teacher educators can engage in (4) challenging their own frames of reference. Corresponding practices parallel the second cluster of practices, but this time they are aimed at raising teacher educators’ own awareness. As such, by participating in a PDI or conducting self-examination, teacher educators can reaffirm their modelling potential [

34]. Finally, (5) raising societal responsiveness to diversity consists of practices associated with teacher educators’ potential to function as change agents in education and society. It may involve doing research on diversity-related topics, engaging in public discussions about diversity in education, or advocating for responsiveness to diversity in institutional or national boards that set out policies [

35].

Additional research on diversity-responsive practices from the framework is still in its infancy. However, a first study, based on interviews with multiple teacher educators [

24], already provides several findings which are informative to our purpose of designing a PDI to foster teacher educators’ diversity-responsive practices. A first conclusion, while teacher educators feel responsible and willing to create qualitative learning environments for all and a more socially just world (i.e., responsiveness to diversity), most of them seem unaware of what corresponding practices from the framework can look like or how their own practices already relate to diversity-responsive education [

17]. Second, some teacher educators named various factors that were perceived as barriers to setting up diversity-responsive practices. For instance, working with big class groups, perceiving the student group as homogeneous, or experiencing a lack of incentives from the institution were reasons for teacher educators to avoid or limit diversity-responsive practices, while other teacher educators denied these barriers [

17]. Finally, teacher educators who engaged more in challenging their own frames of reference (cluster 4) provided examples of practices from all other clusters, seemed to be more aware of how all these practices are connected, and tended to cope better with feelings of insecurity or discomfort that are often linked to diversity-related issues [

17]. This last finding ties in with earlier research on teacher educators, stating that some teacher educators have managed to develop a critical habit of mind, called an inquiry as stance, allowing them to challenge the status quo in education [

36], and thus addressing structural inequalities (in)directly where possible. Based on the findings of this preceding study, we suggest a PDI to foster teacher educators’ diversity-responsive practices can have the following objectives:

Foster an overall critical stance by permanently challenging teacher educators’ frames of reference;

Raise awareness about diversity-responsive practices by providing a framework to analyse and acknowledge current practices;

Increase diversity-responsive practices by facilitating concrete inspiration.

1.2. General Design Principles for PDI with Teacher Educators

Worldwide, teacher educators express the need for ongoing participation in PDIs, specifically targeting their role as teacher educators [

37]. In contrast, systematic approaches to tackle this need are lacking in many countries [

38], reducing PDI to ‘ad hoc’ initiatives with little consideration for effective design [

39]. International awareness of this gap has increased in recent years, leading to more explicit policy ambitions to close it [

40]. Additionally, the research field on teacher educators’ professional development has grown significantly by connecting stand-alone studies and conducting follow-up studies [

41]. In Europe, this is in part due to the International Forum for Teacher Educator Development (InFo-TED), which was purposefully created to develop and share insights into teacher educators’ professional development [

42]. A recent state-of-the-art work by researchers connected to InFo-TED, the book

Teacher Educators and their Professional Development: Learning from the Past, Looking to the Future [

15], made an important contribution to the field. For this study, in particular, the design principles that are formulated for teacher educators’ PDI are very informative [

43]. The researchers compared existing initiatives on local, national, and international levels and combined them with evidence from the research literature [

44,

45]. This resulted in nine general design principles for on-site PDIs [

43], which also apply to a PDI to foster teacher educators’ diversity-responsive practices:

Incorporate ownership of content and process;

Install professional learning communities;

Invest in knowing each other and sharing practices;

Integrate informal and formal learning at the workplace;

Focus on teacher educators’ multi-layered professional identities;

Spread out the programme over time;

Consider the pressure on teacher educators’ time;

Form networks with partners;

Strive for integration of self-reflection and action.

1.3. Context of This Study

The current PDI is designed for higher education-based teacher educators in Flanders, the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium. In Flanders, initial teacher education (ITE) is provided by universities and higher education colleges. The former prepares students to teach in upper secondary education, and the latter offers programmes to become kindergarten, primary, and lower secondary school teachers [

46]. Higher education colleges also provide programmes for special needs education and vocational secondary education. Like in the majority of the member states of the European Union, the teacher educators working in these higher education colleges are not subject to any official quality criteria or benchmarks [

8]. Additionally, as there are no official requirements regarding past teaching experience or research background, Flemish teacher educators constitute a heterogeneous professional group [

43].

In theory, ITEs are responsible for the preparation, induction, and ongoing professionalisation of teacher educators [

43]. However, institutional PDIs specifically designed for teacher educators instead of targeting all lecturers in higher education remain quite rare [

8]. Like in most European countries, PDIs for teacher educators on a national level are rather ‘ad hoc’ or ‘local’ initiatives [

20]. For instance, the Professional Association of Teacher Educators in Flanders (VELOV) occasionally organises inspiring events, like conferences or exchange networks [

47]. However, besides one national programme that was discontinued recently, systematic PDIs in Flanders are lacking [

48]. In this article, it is our goal to describe the design for an evidence-informed teacher educator PDI that could inspire ITE or national policy-makers to systematically install similar initiatives. Since most higher education institutions have developed strategic policy plans about diversity and inclusion [

49], our focus on supporting teacher educators’ diversity-responsive practices promises to be highly relevant.

2. Methods

2.1. Participatory Design

Translating the PDI objectives and general design principles from the literature into an actual PDI is no trivial endeavour. On the contrary, designing a pedagogical intervention, like a PDI, compels us to follow a systematic development process [

50]. Overall, processes suggested by the educational design-based literature have three steps in common: (1) identify and analyse the need for a product (i.e., the PDI), (2) design the PDI, and (3) evaluate the PDI [

51]. In this particular case, we decided to adhere to a participatory design process [

22]. In a participatory design, a researcher involves various stakeholders in one or more phases, with the purpose of tailoring the pedagogical product to its users and their context [

21]. As such, the participatory design process reflects a clear acknowledgement of the situated nature of teacher educator practices [

18]. Participatory design derived from Scandinavian Cooperative Design in the 1960s, “a design approach intended to give users a say in the design of new products and technologies” [

52] (p. 61). Currently, participatory design is used in many fields, like education, as a process that can entail various degrees of collaboration between designers who want to understand users’ situations and users who want to articulate their needs [

53]. When participants are involved equally in all steps of the design, the process might be called co-design or co-creation [

21,

54].

Here, the research team decided to approach stakeholders for different degrees of involvement during the design process. According to the literature on participatory research, stakeholders can be ‘users’, ‘informants’, ‘testers’, or ‘design partners’ [

55]. Evidently, all participating teacher educators would function as users of the PDI. For the identification and analysis of the PDI, our points of contact within the participating teacher education institutions, key policy-makers, and the participants of the PDI were asked to give input, thus being ‘informants’ [

56]. Furthermore, we consulted our professional network of teacher educators to have informal conversations about possible translations of the prior defined design principles to the concrete context. As these contacts provided comments on the PDI design, they can be perceived as ‘testers’ [

55]. Lastly, we strived to find a few willing stakeholders within the participating institutions to equally invest in the design process, making them ‘design partners’. Depending on the institutional context, this request to invest equally in the design process could be granted.

2.2. Selection Process

Due to pragmatic reasons, we limited our collaboration to two higher education colleges and aspired to facilitate parallel PDIs for each institution. Convenience sampling was used [

57] to find higher education colleges and participants within these institutions willing to participate. Prior to the design process of this PDI, our research team had already collaborated with both higher education colleges. Our contact at higher education college A (HEC A) was the head of the teacher education department; at higher education college B (HEC B), they were a duo of teacher educators that were assigned an institutional project about professional development regarding diversity-related topics. Consequently, a certain interest in participation in the PDI was already in place at the institutional level.

After agreeing to collaborate, we discussed with our points of contact the degree of participatory design that was possible. One key policy-maker per institution who is involved in institutional policy about professionalisation and diversity and inclusion would be approached as an informant of the PDI, as well as all group participants. Respectively, this would allow us to gain insight (1) into the institutional context of both participating higher education colleges and (2) into the individual professional development needs of the participants themselves. Furthermore, at HEC A, we were put in contact with multiple teacher educators who might be willing to be design partners, but unfortunately, without any positive reception. The extensive work pressure or feeling insecure about their expertise in diversity-related issues were the main reasons for this. At HEC B, our contact duo did adopt the role of design partner since it could be perceived as a part of the institutional assignment they were already given. The duo consists of a man with almost 40 years of experience in ITE and a woman with more than 10 years of experience in ITE and some experience in compulsory education. Both have a master’s degree, were given a research assignment, and are involved in pedagogy-oriented and practicum-oriented courses. Additionally, the man is responsible for some subject-specific courses in the primary and special needs programmes, while the woman is involved in the primary and secondary education programmes.

Our points of contact were asked to identify a respective key policy-maker. At HEC A, this turned out to be our contact person. At HEC B, this was someone who had been working on the management level of the teacher education department. Participants for the PDI were found via calls placed by our respective contact persons within each institution. All teacher educators who have a teaching assignment within one or more teacher education programmes were eligible for registration. The maximum number of participants per group was set at 12 to ensure meaningful discussions and a personal approach. Eventually, 9 teacher educators at HEC A and 10 at HEC B voluntarily subscribed to the semi-structured interviews and the PDI.

Table 1 presents an overview of the participating teacher educators’ demographics per higher education college. Moreover, all teacher educators presented as being of White-European descent.

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

Following a small-scale qualitative data collection process, the first author conducted semi-structured interviews [

57] with both policy-makers (

n = 2) and all participating teacher educators (

n = 19). The interviews were held during December 2022 and January 2023, both in person and online, using Microsoft Teams. All interviews were audio-recorded, resulting in conversations that lasted from 32 to 61 min. Prior to the interviews, participants obtained detailed informed consent, on which they all agreed [

57]. It explains, amongst others, how participants can withdraw at any moment without consequences and how data will be pseudonymized and stored.

Interview protocols were developed for the policy-makers and the teacher educators, respectively [

58]. However, the start of both protocols was similar: informing about the aim of the PDI, allowing participants to ask clarifying questions, and checking their background characteristics (e.g., prior professional experience, additional tasks in ITE). In the second part of the interview with the policy-makers, we probed for information about the structure of the teacher education department (e.g., number of teacher educators and students, available programmes and their physical location, structural collaboration), current institutional policies about professionalisation, and diversity and inclusion. In the second part of the interview with the teacher educators, they were asked to share their perceptions of the concepts of diversity and approaching diversity; their concrete practices to approach diversity; their thoughts about barriers to setting up diversity-responsive practices; and their concrete expectations of the PDI. Before ending the interview, participants were given the opportunity to share their remaining thoughts and comments.

Next, pseudonymized verbatim transcriptions of the audio recordings were made to prepare the data for analysis. Since the data was collected to provide straightforward contextual information about the higher education colleges and participating teacher educators, a descriptive analysis was conducted, limited to summarizing characteristics at an institutional and participant group level. Together with the educational literature, these characteristics were informative to the repeated and iterative discussions with the research team, the design partners, and the informal teacher educator contacts about design choices. All discussions took place between September 2022 and January 2023. Finally, based on these discussions, overall design choices were made for the PDI, and, where meaningful, tailored alterations to the respective contexts were incorporated.

3. Results

Within the scope of this article, the results of the first two phases of the participatory design process are presented. First, we summarise the information gathered via the data collection to identify the particularities in both institutional contexts as well as both participant groups’ needs. Second, we introduce the design of the PDI and describe the overall and context-tailored design choices that were made. Deliberately leaving out the impact evaluation of the PDI in this article allows us to go into more detail about the design itself and to create a more unique article for the design literature. Nevertheless, the impact evaluation will still be conducted and reported on to finish the design process.

3.1. Identification of the Institutional Contexts

Based on the interviews with key policy-makers, we were able to define some important institutional characteristics of each higher education college. An overview of these characteristics is displayed in

Table 2. The teacher education department at HEC A can be characterised as a medium-sized department. It is spread across two campuses in one large Flemish city. The department is divided into four ‘programme centres’, each led by a head, a team coordinator, and one or more curriculum coordinators, depending on the number of curriculum programmes they provide. The main head of the department supports the different programme centres and facilitates the translation of institutional policy into departmental policy. At HEC B, the teacher education department is a large department, providing multiple programmes in three different cities across a rural Flemish province. As such, the organisational structure is more complex: a board per campus for every programme at these campuses and for similar programmes across campuses (e.g., all primary education programmes). While similar programmes at the various campuses used to be organised on a campus level, curricula are increasingly aligned on a central level (e.g., all kindergarten programmes have the same courses and goals). However, each programme at every campus currently has a head. Additionally, two coaches are appointed to support the different governance boards and facilitate the alignment of departmental policy to central institutional policy.

Regarding HEC A’s diversity and inclusion policy, the institutional focus in recent years has been mostly on attracting students and lecturers from minoritised groups. Currently, a shift is observed towards adapting to the institutional environment in order to increase the retention of those who are already participating in the programmes. In the newest policy plan, an explicit strategic goal to transition towards an inclusive institution is consolidated. This means that both students and employees should be able to feel included. However, coordinated actions and research to support this transition are still limited within the institution. Also, on the level of the teacher education department, the translation of the new strategic goal is still in its infancy. There have been some isolated efforts of single or groups of teacher educators to take action for this policy goal, for instance, by rethinking the curriculum on citizenship. HEC B states creating inclusive learning environments is one of its four main policy ambitions. This is reflected in the existence of a diversity working group that was structurally installed and is mandated to consider implications for education and research. This group has, for example, developed a tool to scan learning materials on their inclusiveness. They also facilitate research proposals to support inclusion within the institution, focusing, amongst others, on barriers for ethnic minoritised students or micro-aggressions. Furthermore, at the teacher education department, an additional project was assigned to a duo of teacher educators allowing them to focus on internal professional development activities regarding diversity-related topics. It is a two-year assignment to which the different boards in the department have allocated extra resources. The temporary character, however, creates uncertainty about the continuation of sustainability.

Professionalisation of teacher educators in both higher education colleges happens quite similarly. Teacher educators can attend internal and external programmes. On the institutional as well as the departmental level, events are organised systematically, such as guest lectures or workshops. Within the departments, the events might be linked to a yearly theme. At HEC B, diversity and inclusion had already been the theme a few years ago. While such events are often experienced as inspirational by HEC A’s participating teacher educators, they rarely lead to sustainable changes in their practices; how, and even if, they engage in professional development trajectories is left to their own choosing. Not much incentive to professionalise is experienced by the teacher educators. However, during performance reviews at both institutions, teacher educators are expected to account for how they engaged in any form of professionalisation in the past year.

3.2. Identification of the Participant Groups’ Needs

The interviews (n = 19) with the participating teacher educators helped us describe common professional development needs and the prior knowledge of each group. When examining the professional development needs expressed by teacher educators, three commonalities for both groups could be found: a need for (1) frameworks, (2) opportunities to share, and (3) evidence-informed practices. First, teacher educators were looking for conceptual frameworks that could be used to analyse their practices. According to them, approaching diversity in education is a complex matter that can touch upon many related themes. Frameworks function as simplified representations of reality and, thus, might support a deeper understanding of the complex reality. It might also offer vocabulary to describe one’s own practices and experiences. A second need involved the desire to exchange ideas with colleagues. This is related to the fact that teacher educators experience a lot of pressure in their job, and structural discussion about a professional development topic is usually scarce. Therefore, the participants claimed to benefit from actual time to inspire each other with concrete practices and viewpoints. Lastly, in both groups, the need was expressed to become acquainted with evidence-informed practices about approaching diversity. Some said they were satisfied if they could listen to findings from recent research; others were also eager to experience such practices during the PDI.

Surprisingly, most participants explicitly stated they had no professional development needs regarding specific diversity-responsive practices or particular diversity-related content. Instead, they said they were open to all kinds of input related to approaching diversity. Only a few participants did specify a content need. In the HEC A group, some wanted to know more about how to deal with resistance from colleagues on the topic of diversity and inclusion. These were people who often felt alone in their programme or department to put the topic on the agenda. In HEC B, this need was less present, potentially because the topic had already been placed more structurally on the agenda. Nevertheless, one person at HEC B did mention a desire to better inspire other colleagues to invest in the topic, which could indirectly also indicate some resistance at HEC B. This teacher educator suggested clear frameworks and practical examples that could help with this, hence reflecting the prior described common needs. In addition, participants of HEC B were enthusiastic about becoming more familiar with the educational tools (e.g., the scan for inclusiveness) and research that had been developed within their own institution regarding diversity and inclusion. Most who knew about this had not yet explored the tools and research.

Finally, we discovered that most participating teacher educators already used a broad definition of diversity and could give examples of many diversity-responsive practices they set up. Even though terminology was often not in line with our own conceptualisation of responsiveness to diversity, both groups clearly reflected a decent amount of prior knowledge. At HEC A, this might be ascribed to the fact that most participants have a teaching assignment in general pedagogical courses, in which they themselves address topics of diversity with student teachers. At HEC B, prior collective professionalisation about the topic on the departmental level or the structured attention given to it on an institutional level might explain the prior knowledge. According to most participants, their own sense of responsibility for the matter, as well as their professional beliefs about education, compels them to invest in the topic more than other colleagues might do in their department. Consequently, both groups of participants already agree on the importance of diversity-responsive education and the role of teacher educators in it, thus needing little persuasion for the importance of the topic.

3.3. Design of the PDI

Considering the three objectives (see

Section 1.1) and nine general design principles (see

Section 1.2) that were set out for a PDI to support teacher educators’ diversity-responsive practices, the research team repeatedly discussed design options with both testers and design partners (see

Section 2.1). Following the participatory design process, these discussions were held prior to and following the data collection with the key policy-makers and participating teacher educators (see

Section 3.1 and

Section 3.2). All these elements were carefully taken into account to jointly decide on the final design, resulting in a PDI consisting of three distinct phases: (1) an immersive two-day programme, (2) individual experimentation accompanied by a monthly coaching session, and (3) a reflective closing moment.

Table 3 summarises information about the timing, content focus, and pedagogical methods of each phase while also referencing the general design principles that substantiate the respective phases.

Three of our key design choices did not fit into the list of general design principles. Therefore, they were added as ‘extra’ in

Table 3, and some further explanation is given. First, in order to reach the PDI’s first objective (i.e., to foster an overall critical stance by permanently challenging teacher educators’ frames of reference), it was thought necessary that the PDI uphold the same condition that teacher educators uphold when challenging their students’ frames of reference: a safe learning environment. By constantly investing time in getting to know each other and inquiring into the needs of participants without forcing anything, we aim to create an environment where everyone feels welcome. bell hooks’ idea of engaged pedagogy [

7] and Ruth Cohn’s theme-centred interactional method [

59] were inspirational to us in order to (1) model pedagogy for safe learning environments [

12]. Additionally, the first session of the two-day immersion programme is deliberately focused on gradually revealing oneself to others. Due to the size and organisational structure of HEC B, the corresponding teacher group is expected to need more time to become acquainted with one another. Therefore, the design partners at HEC B developed an extra, accessible activity based on intersectionality theory.

A lot of time is invested in gradually (2) installing a common frame of reference to talk about diversity-responsive education. The second session of the two-day programme is completely devoted to existing research on diversity-responsive education. First, important concepts like inclusion, discrimination, and privilege are defined by calling upon participants’ prior knowledge and having discussions about it. Hence, a decent amount of prior knowledge in both groups is made use of. Next, the conceptual framework on teacher educators’ diversity-responsive practices is introduced to expand the common vocabulary for the remaining part of the PDI. Finally, other relevant frameworks (e.g., VU Mixed Classroom by Ramdas et al., 2019; Index of Inclusion by Booth & Ainscow, 2002) [

60,

61] are linked to diversity-responsive practices where possible. The introduction of frameworks meets an explicit need from the participants and responds to the second PDI objective to raise awareness about diversity-responsive practices.

Finally, the third PDI objective to increase diversity-responsive practices is reached by devoting different sessions of the two-day programme to inspiration about specific practices. In each session, active learning methods are used to introduce evidence-informed practices and create opportunities to share professional experiences, this way simultaneously meeting two common needs of participants. The design partners at HEC B also linked institutional tools and existing research to some sessions in order to make the teacher educators more familiar with it. Consequently, they facilitate the corresponding sessions and invite relevant researchers to present their own work. To meet the HEC A group’s specific need to discuss resistance to diversity and inclusion ambitions, a guest speaker is invited. Moreover, an online environment was developed with lots of inspiration for practices, speaking to different learning styles (e.g., reading materials, clips, podcasts…) that the teacher-educators could (but were not compelled to) explore. It is believed that participants are likely to visit the platform given the high sense of responsibility that was observed in both groups to engage in diversity-responsive practices. However, what we think is of utmost importance to make sure that participants translate inspiration into increased practices is to use the last session of the two-day programme to select one or more foci and plan possible actions in their daily work during the common months. The participants are also asked to plan subsequent peer-coaching sessions in a duo or trio in order to (3) keep each other accountable to experiment. This was deemed necessary because teacher educators might lose sight of their professionalisation goals due to time constraints or work pressure. A reflective instrument based on the concept of a personal development plan [

62] was developed to facilitate this process. The instrument also incorporates guidelines for the peer-coaching session inspired by Clement’s inspirational coaching idea [

63]. Neither is forced on the participants as they can decide themselves on the length and the form of the coaching sessions.

4. Discussion

The main goal of this study was to provide insight into the design of a PDI to foster teacher educators’ responsiveness to diversity. Therefore, we were compelled to follow a systematic development process [

50]. In particular, a participatory design process was set up because it aims to tailor a pedagogical product, like a PDI, to its users and their contexts [

51]. It allows us to take into account the situated nature of teacher educator practices [

18]. After identifying the institutional context and participant groups’ needs, we presented an overall PDI design consisting of three phases: (1) a two-day immersive programme, (2) individual experimentation with monthly coaching, and (3) a reflective closing moment. We have argued how the overall design accommodates for the specific contexts, as well as the prior-defined objectives [

17]. We also showed how the DPI had considered the general design principles suggested by the educational literature [

43] and incorporated extra design choices that did not fit into the list of general design principles. A strong merit of this article is the addition of three new design principles to the literature: (1) model pedagogy for safe learning environments; (2) install a common frame of reference; and (3) embed accountability incentives.

Since we build on evidence-informed design principles that have been supported by the literature, we assume a high probability that the PDI will be experienced as meaningful by the participants. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that to complete the design process, the PDI has yet to be implemented and evaluated [

51]. Currently, statements about the execution or the impact of the PDI on the participants are not possible. Even though it is our sincere ambition to measure the impact of the executed PDI via a mixed-method approach, for this article, we deliberately chose to focus solely on the design and its preceding process. We argue that across the educational literature, attention is increasingly directed towards the effects of interventions [

64], often at the expense of detailing concrete descriptions of interventions and the decisions that have led to these interventions. Nonetheless, it is the description of interventions that can be of practical inspiration for educational professionals and policy-makers. Moreover, such rich descriptions explicate how theoretical and evidence-informed insights can be translated to practical solutions while potentially also making suggestions for new theories [

65]. By focusing on the design of our PDI, we want to stress its own value.

The presented PDI to support teacher educators’ responsiveness to diversity is unique in more ways than one. First, evidence-informed PDIs for teacher educators are rare in the literature, especially when it is focused on how they can approach diversity [

15]. Second, we did not set out to create a blueprint that can be applied in any context or with any group of teacher educators. Rather, we suggest that careful contextualisation is needed if sustainable change in teacher educators’ professional development is desired. For instance, the current PDI is tailored to participants who have a decent amount of prior knowledge and already feel responsible for investing in responsiveness to diversity. As this is not the case for all teacher educators, alterations would be needed for other starting positions. Similarly, both groups of participants presented as predominantly white and female, probably leading to different needs than groups with a different composition. Third and following the latter, a participatory design process was used to contextualise the PDI. By talking with various stakeholders, multiple existing resources from the participating institutions were revealed and, to the extent possible, included in the PDI design. Amongst others, guest speakers, materials regarding diversity and inclusion policy, or corresponding research were incorporated. Careful consideration of these resources stands to provide great benefits to any PDI, as it heightens both embeddedness in the local context and ownership alike. Consequently, we propose that involving stakeholders with various degrees of involvement can be an adequate approach to reveal information that structures possibilities for professionalisation [

42].

Furthermore, what is most interesting about the design of this particular PDI is that we made some key design choices that did not fit into the list of general design principles we started from [

43]. Even though these choices are important in the context of diversity-responsive education, we believe they can also be integrated into teacher educator PDIs with a different focus. As such, this manuscript adds to the literature by adding three general design principles for teacher educator PDI to the existing list: (1) model pedagogy for safe learning environments; (2) install a common frame of reference; and (3) embed accountability incentives. The first added design principle implies that facilitators have an important task to make everybody feel welcome in the PDI. Only then will participants open up for sustainable change in their thoughts or behaviours [

7,

29], even when the topic is ideologically charged, like diversity and inclusion, or, according to some scholars, anything that involves education [

10]. In every PDI, but especially in the context of diversity-responsive education, this means to teach as you preach and model corresponding behaviour. The second added design principle, to install a common frame of reference, allows teacher educators to build a common vocabulary, connect theory to their practices, and analyse these practices via a common lens. It is somewhat surprising that this was not yet a general design principle of teacher educator PDIs. In the literature on teacher educator professional development, a framework is often seen as the starting point [

66]. We theorise this principle might be so taken for granted by the field that it is seldom made explicit. However, since most participants specifically expressed a need for frameworks, we think it should become an explicit design principle. The last added design principle, to embed accountability incentives, is particularly useful in PDIs that are spread out over a longer period of time and build in a decent amount of ownership for participants regarding what they implement in their daily practice. Teacher educator PDIs in the literature are often shorter or more controlled by a researcher than this PDI [

15]. Yet, the integration of the second phase of our PDI (i.e., the individual experimentation accompanied by a monthly coaching session) was purposefully installed to resemble the actual situation of teacher educators in which researchers are not present to install incentives. Here, the planned monthly peer-coaching sessions ensure that participants are reminded of the PDI’s goals and made responsible to experiment so they have something to share with colleagues during the coaching sessions. For a sustainable PDI, we find the embedding of accountability as a design principle indispensable. Simultaneously, we do acknowledge that, with regard to all three of the new design principles presented in this article, some caveat concerning their impact is in place. The evaluation of the PDI should also investigate these principles more in-depth to determine if they pass as design principles for future teacher educator PDIs. Additional design research is needed as well to strengthen their evidence-informed value.

It must also be stated that designing a PDI for teacher educators via participatory design entails some challenges. To start with, the process can be quite time-consuming. It will not be possible at every higher education college to find people who can manage the process or take up the role of design partner. At HEC B, the latter was possible because our contact duo was given a clear mandate, while this was not the case at HEC A. Structural aspects like the willingness of institutional and departmental boards to allocate time and resources in the participatory process are essential. Moreover, such structural aspects are also important to attract teacher educators to PDIs who have lower feelings of responsibility or lower prior knowledge than the participants in this design. If little or no incentive is given by the leadership, some teacher educators might never engage in professionalisation, possibly holding back the improvement of teacher education programmes. Finally, the act of balancing multiple roles throughout the design process should be carried out with caution. In this particular case, the principal researcher was a data collector and designer, and he is also the co-facilitator of the PDI. While researchers are trained to keep a certain distance from participants to not skew research results, the task of tailoring the PDI to participants’ needs now demands the opposite. Awareness of this seemingly paradoxical role and careful contemplation of it are thus recommended. Here, transparent communication with the design partners and critical discussions within the research team occurred.

In conclusion, this study adds to the field in a practical and theoretical way. Practically, policy-makers, as well as teacher educators themselves, can find inspiration to design their own PDIs to support responsiveness to diversity and make tailored alterations. Theoretically, three new design principles are added to the literature on teacher educator professional development, while the limited literature on teacher educator PDIs about approaching diversity is expanded as well.